Verotoxin A Subunit Protects Lymphocytes and T Cell Lines against X4 HIV Infection in Vitro

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. PBMC Antigen Expression

| (a) Markers of PHA/IL-2 activated PBMC lymphoid subsets | |||||

| Antigen | % positive | ||||

| CD3-T cells | 97.4 | ||||

| CD14-monocytes | 2.0 | ||||

| CD19-B cells | 1.5 | ||||

| (b) Cell surface marker labeling of VT treated PHA/IL-2 activated PBMCs | |||||

| Treatment | %CD3+ve | ||||

| Untreated | 97.4 | ||||

| 1 µg/mL VT1 | 95.7 | ||||

| 1 µg/mL VT1A | 94.2 | ||||

| 1 µg/mL VT1B | 97.9 | ||||

| (c) Effect of VT1A treatment on CD4 positive vs. CD8 positive T cell composition | |||||

| Treatment | % CD3+ T cells * | % CD4+ CD3+ T cells * | % CD8+ CD3+ T cells * | CD4+ CD8+ T cells * | |

| Untreated Control | 85.1 | 41.7 | 47.0 | 0.9 | |

| 1 µg/mL VT1A | 88.1 | 43.5 | 49.2 | 0.9 | |

2.2. Metabolic Labeling of PBMC GSLs

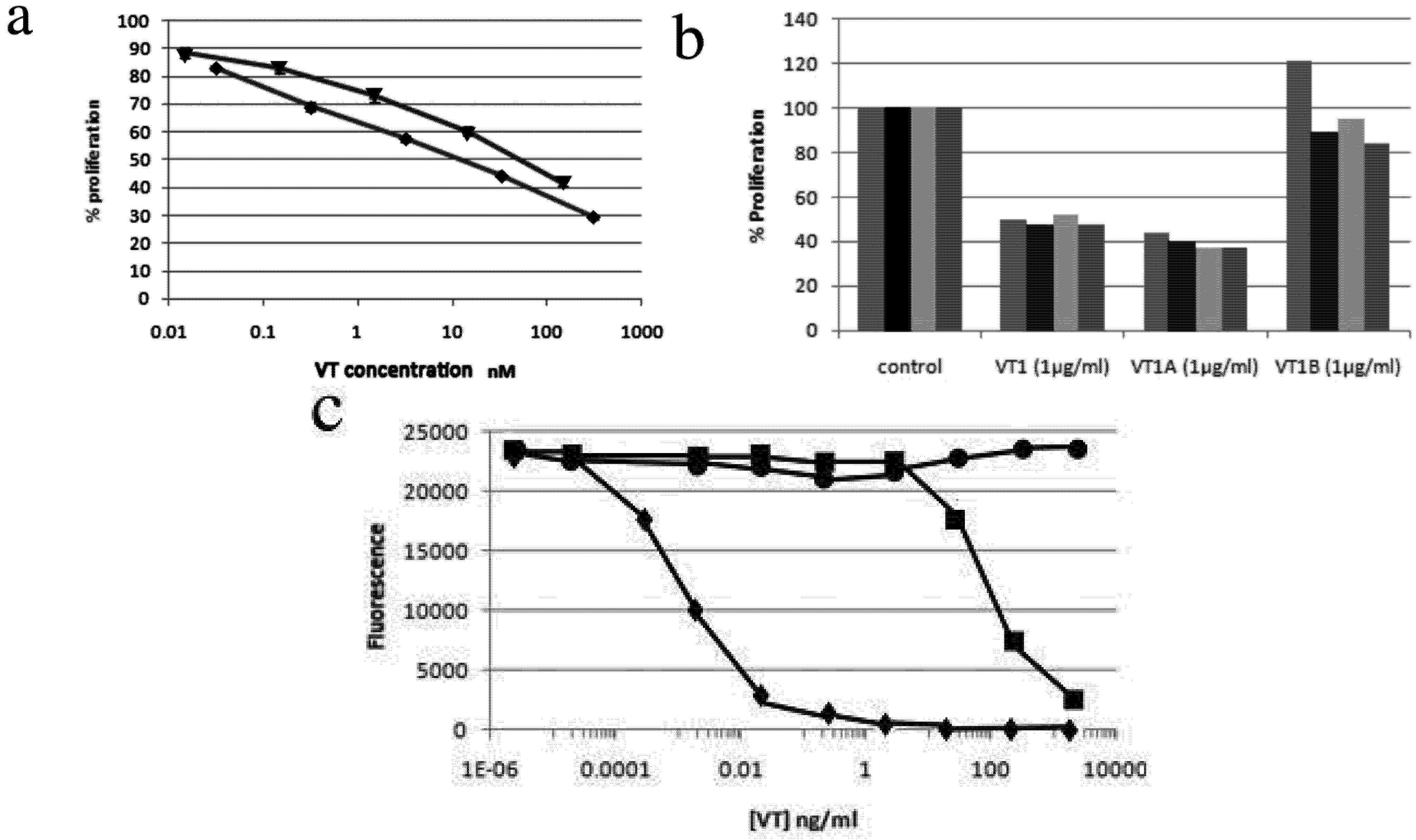

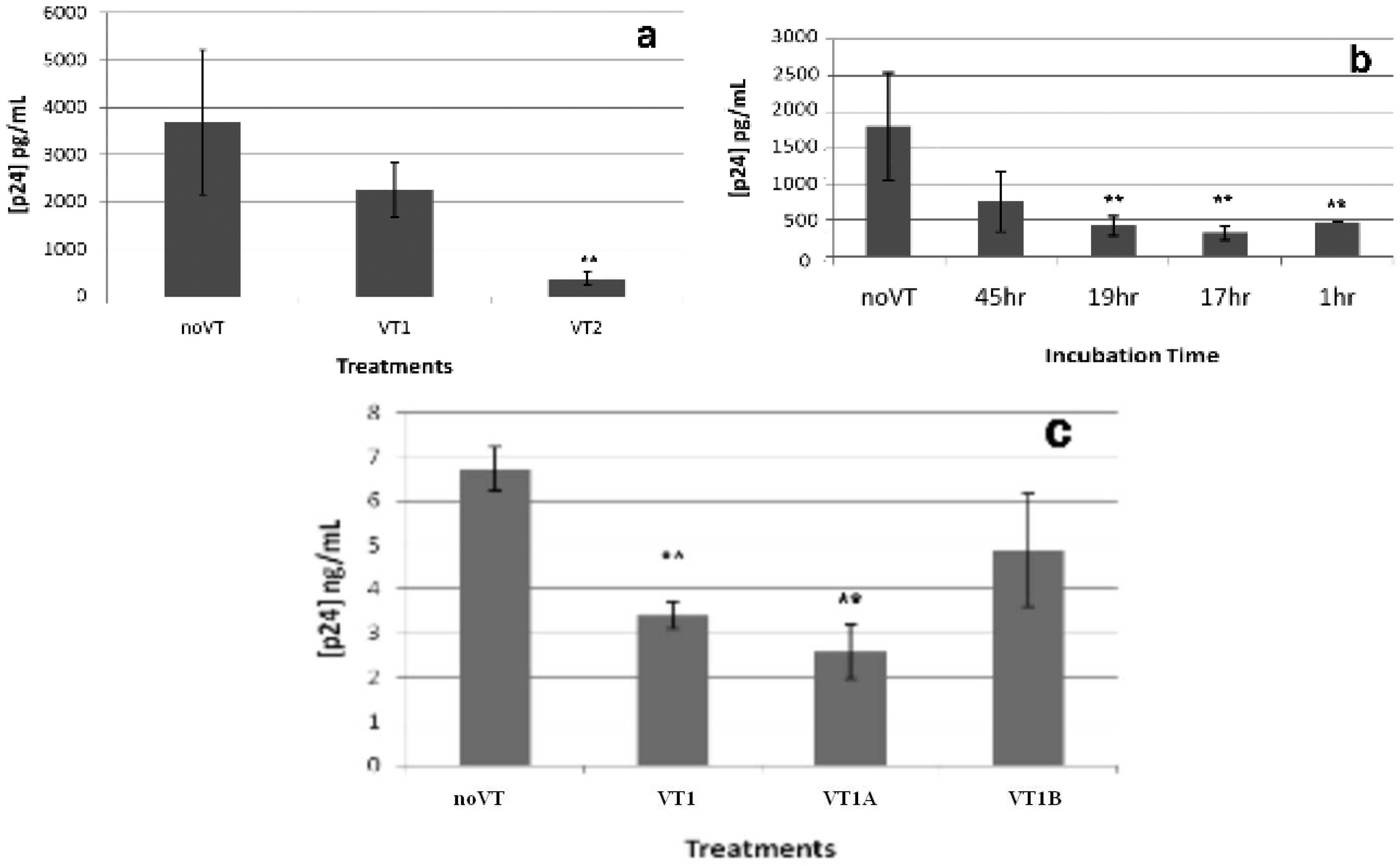

2.3. Effect of VT on HIV PBMC Infection

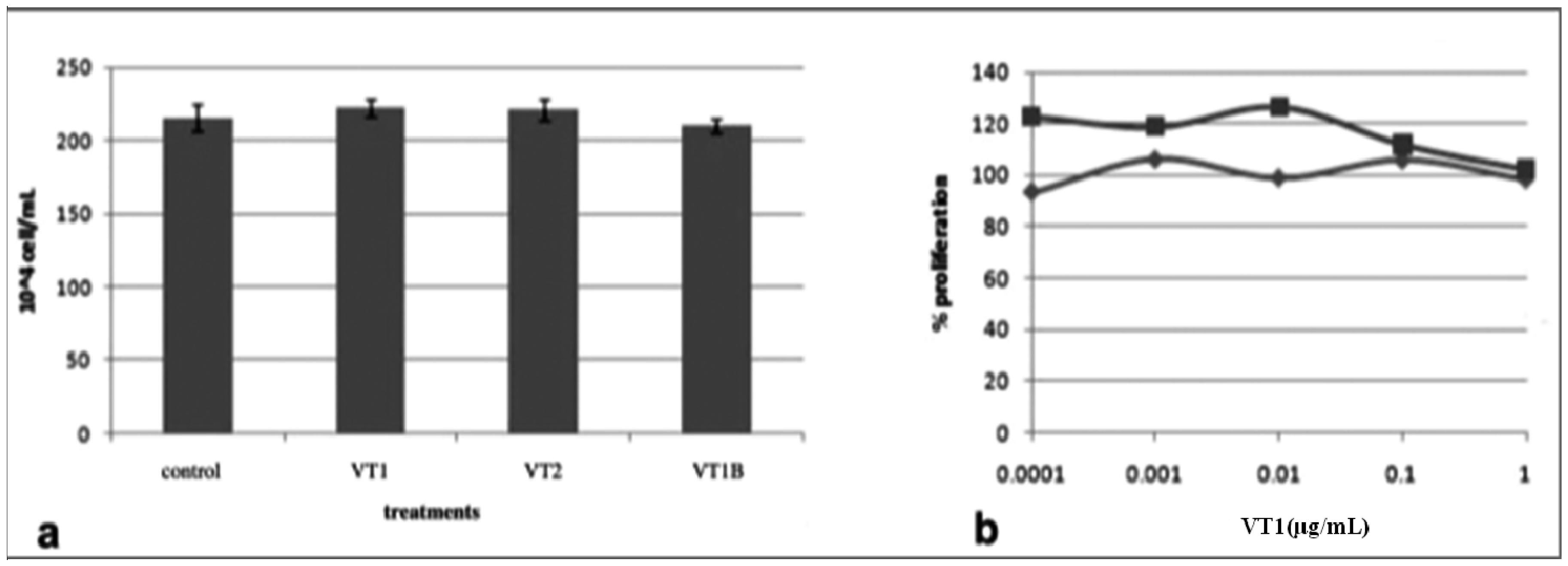

2.4. Comparison of VT Subunits for Protection of PBMCs against HIV Infection

2.5. VT also Inhibits Jurkat T-Cell Infection by HIV-1

2.6. Gene Expression Array Analysis of VT1A Treated PHA/IL-2-Activated PBMCs

| Symbol | Definition | Fold Change | adj. p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIST1H4B | histone cluster 1, H4b | 5.22 | 0.000185 |

| HIST1H4H | histone cluster 1, H4h | 5.01 | 0.000192 |

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1, transcript variant 2 | −4.50 | 0.000192 |

| HIST1H4F | histone cluster 1, H4f | 3.95 | 0.000363 |

| INDO | indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3 dioxygenase | −3.84 | 0.000466 |

| CSF2 | colony stimulating factor 2 (granulocyte-macrophage) | 3.63 | 0.000515 |

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1, transcript variant 1. | −3.94 | 0.000515 |

| LYZ | lysozyme (renal amyloidosis) | −3.51 | 0.000547 |

| GADD45B | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, beta | 3.43 | 0.000547 |

| CCL24 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 24 | −3.45 | 0.000547 |

| IL9 | interleukin 9 | 3.47 | 0.000699 |

| IL9 | interleukin 9 | 3.17 | 0.00112 |

| TM4SF19 | transmembrane 4 L six family member 19 | −3.11 | 0.00112 |

| IL8 | interleukin 8 | −3.20 | 0.00151 |

| SLC11A1 | solute carrier family 11 (proton-coupled divalent metal ion transporters), member 1. | −3.33 | 0.00154 |

| IL1B | interleukin 1, beta | −2.78 | 0.00317 |

| MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | −2.73 | 0.00358 |

| HIST2H4A | histone cluster 2, H4a | 2.71 | 0.00569 |

| TAC1 | tachykinin, precursor 1, transcript variant alpha | 2.62 | 0.00627 |

| PPP1R15A | protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 15A | 2.60 | 0.00627 |

| TYROBP | TYRO protein tyrosine kinase binding protein, transcript variant 1. | −2.80 | 0.00627 |

| GNLY | granulysin, transcript variant NKG5 | −2.52 | 0.00733 |

| OSM | oncostatin M | 2.49 | 0.00758 |

| TM4SF19 | PREDICTED: transmembrane 4 L six family member 19, transcript variant 2 | −2.60 | 0.00758 |

| HIST1H2AC | histone cluster 1, H2ac | 2.49 | 0.00972 |

| OR8H2 | olfactory receptor, family 8, subfamily H, member 2 | 2.51 | 0.00972 |

| FOS | v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 2.58 | 0.972 |

| TNFSF4 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 4 | 2.35 | 0.0185 |

| IL8 | interleukin 8 | −2.29 | 0.0185 |

| FOSB | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B | 2.32 | 0.0185 |

| HIST1H2BF | histone cluster 1, H2bf | 2.34 | 0.0220 |

| GNLY | granulysin, transcript variant 519 | −2.24 | 0.0223 |

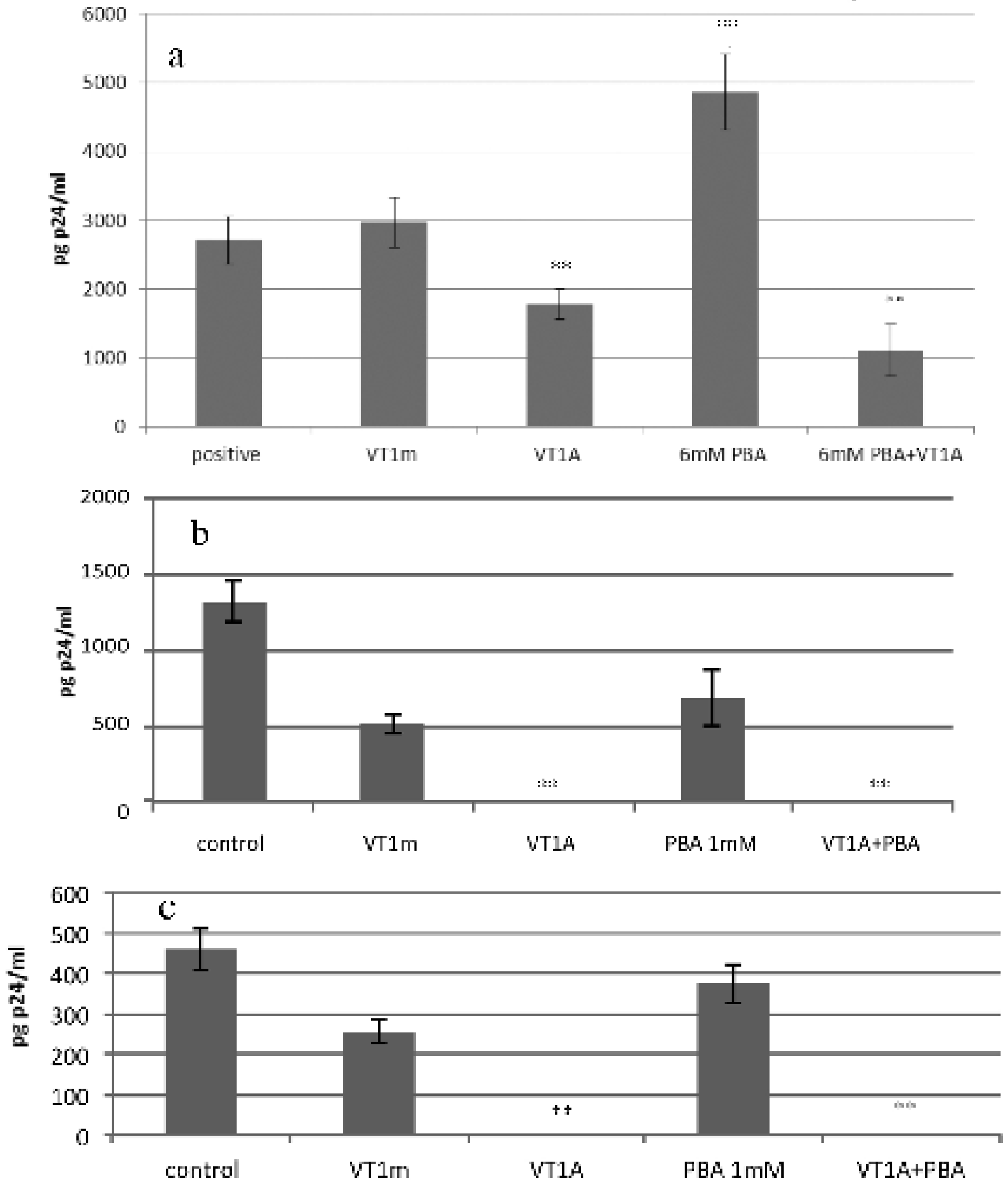

2.7. VT1 Blocks HDAC Inhibitor Effect on HIV Infection

2.8. Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Cell Lines

3.2. Isolation and Activation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs)

3.3. HIV Infection

3.4. Preparation of VT1 and VT2

3.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.6. Protein Synthesis

3.7. Flow Cytometry

3.8. RNA Extraction

3.9. Human Gene Expression Array Analysis

3.10. Statistics

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Zoja, C.; Buelli, S.; Morigi, M. Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: Pathophysiology of endothelial dysfunction. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2010, 25, 2231–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karch, H.; Friedrich, A.W.; Gerber, A.; Zimmerhackl, L.B.; Schmidt, M.A.; Bielaszewska, M. New aspects in the pathogenesis of enteropathic hemolytic uremic syndrome. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2006, 32, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Tsurugi, K.; Yutsudo, T.; Takeda, Y.; Ogasawara, T.; Igarashi, K. Site of the action of a vero toxin (VT2) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and a Shiga toxin on eukaryotic ribosomes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988, 171, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.K.; O’Brien, A.D.; Ackerman, E.J. Shiga toxin, Shiga-like toxin II variant, and ricin are all single-site RNA N-glycosidases of 28 S RNA when microinjected into Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 596–601. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, T.; Tokuda, N.; Numata, S.; Ito, M.; Ohta, M.; Kawamura, K.; Wiels, J.; Urano, T.; Tajima, O.; Furukawa, K.; Furukawa, K. Targeted disruption of Gb3/CD77 synthase gene resulted in the complete deletion of globo-series glycosphingolipids and loss of sensitivity to verotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 10230–10235. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, P.; Lingwood, C. Membrane-cytosolic translocation of Verotoxin A1-subunit in target cells. Microbiol 2007, 153, 2700–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Thayer, D.A.; Chang, A.Y.; Best, M.D.; Hoffmann, J.; Head, S.; Wong, C.-H. Carbohydrate microarray for profiling the antibodies interacting with Globo H tumor antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Beutin, L.; Geier, D.; Steinruck, H.; Zimmermann, S.; Scheutz, F. Prevalence and some properties of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli in seven different species of healthy domestic animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 2483–2488. [Google Scholar]

- Ferens, W.A.; Hovde, C.J. Antiviral activity of shiga toxin 1: Suppression of bovine leukemia virus-related spontaneous lymphocyte proliferation. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4462–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferens, W.A.; Halver, M.; Gustin, K.E.; Ott, T.; Hovde, C.J. Differential sensitivity of viruses to the antiviral activity of Shiga toxin 1 A subunit. Virus Res. 2007, 125, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferens, W.A.; Hovde, C.J. The non-toxic A subunit of Shiga toxin type 1 prevents replication of bovine immunodeficiency virus in infected cells. Virus Res. 2007, 125, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, I.; Ferens, W.A.; Stone, D.M.; Hovde, C.J. Antiviral activity of shiga toxin requires enzymatic activity and is associated with increased permeability of the target cells. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.; Branch, D.R.; Mylvaganam, M.; Chark, D.; Ma, X.Z.; Sakac, D.; Binnington, B.; Fantini, J.; Puri, A.; Blumenthal, R.; Lingwood, C.A. A novel soluble mimic of the glycolipid globotriaosylceramide inhibits HIV infection. AIDS 2006, 20, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Binnington, B.; Sakac, D.; Lingwood, C.A.; Branch, D.R. CD4+ T-cells are unable to express the HIV natural resistance factor, globotriosylceramide. 2012. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar, S.; Sakac, D.; Binnington, B.; Branch, D.R.; Lingwood, C.A. Induction of HIV resistance: Cell susceptibility to infection is an inverse function of globotriaosyl ceramide levels. Glycobiology 2009, 19, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, N.; Olsson, M.L.; Ramkumar, S.; Sakac, D.; Yahalom, V.; Levene, C.; Hellberg, A.; Ma, X.Z.; Binnington, B.; et al. The human Pk histo-blood group antigen provides protection against HIVinfection. Blood 2009, 113, 4980–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, D.; Mills, G. pp60c-src expression is induced by activation of normal human T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 3678–3685. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Murakami, A.; Johnson, R.P.; Sui, J.; Cheng, J.; Bai, J.; Marasco, W.A. Optimization of ex vivo activation and expansion of macaque primary CD4-enriched peripheral blood mononuclear cells for use in anti-HIV immunotherapy and gene therapy strategies. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2003, 32, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, D.M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and HIV latency. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2 0011, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontiki, E.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs). Structure—Activity relationships: History and new QSAR perspectives. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 32, 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.X.; Teel, L.D.; Judge, N.A.; O’Brien, A.D. Genetic toxoids of Shiga toxin types 1 and 2 protect mice against homologous but not heterologous toxin challenge. Vaccine 2006, 24, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, A.A.; Lingwood, C.A. Capping and receptor mediated endocytosis of cell bound verotoxin(Shiga-like toxin) 1; Chemical identification of an amino acid in the B subunit necessary for efficient receptor glycolipid binding and cellular internalization. J. Cell. Physiol. 1994, 161, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deurs, B.; Sandvig, K. Furin-induced cleavage and activation of Shiga toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 10817–10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvig, K.; Bergan, J.; Dyve, A.B.; Skotland, T.; Torgersen, M.L. Endocytosis and retrograde transport of Shiga toxin. Toxicon 2010, 56, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzan, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Marsden, P.A. Verotoxin and ricin have novel effects on preproendothelin-1 expression but fail to modify nitric oxide synthase (ecNOS) expression and NO production in vascular endothelium. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 101, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzziello-Pellegrini, T.N.; Yuen, D.A.; Page, A.V.; Patel, S.; Soltyk, A.M.; Matouk, C.C.; Wong, D.K.; Turgeon, P.J.; Fish, J.E.; Ho, J.J.; et al. The CXCR4/CXCR7/SDF-1 pathway contributes to the pathogenesis of Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigotti, M.; Alfieri, R.; Sestili, P.; Bonelli, M.; Petronini, P.G.; Guidarelli, A.; Barbieri, L.; Stirpe, F.; Sperti, S.; et al. Damage to nuclear DNA induced by Shiga toxin 1 and ricin in human endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesh, V.L. Induction of apoptosis by Shiga toxins. Future Microbiol. 2010, 5, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigotti, M.; Carnicelli, D.; Arfilli, V.; Rocchi, L.; Ricci, F.; Pagliaro, P.; Tazzari, P.L.; Vara, A.G.; Amelia, M.; Manoli, F.; Monti, S. Change in conformation with reduction of alpha-helix content causes loss of neutrophil binding activity in fully cytotoxic Shiga toxin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 34514–34521. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.G.; Huang, P.L.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, P.L.; Kong, X.P.; Lee-Huang, S. A new activity of anti-HIV and anti-tumor protein GAP31: DNA adenosine glycosidase—Structural and modeling insight into its functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, S.; Kutky, M.; Hudak, K.A. Pokeweed antiviral protein increases HIV-1 particle infectivity by activating the cellular mitogen activated protein kinase pathway. PLOS One 2012, 7, e36369. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, M.; Gunji, Y.; Yamasaki, S.; Takeda, Y. Shiga toxin activates p38 MAP kinase through cellular Ca2+ increase in Vero cells. FEBS Lett. 2000, 485, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckun, F.M.; Bellomy, K.; O’Neill, K.; Messinger, Y.; Johnson, T.; Chen, C.L. Toxicity, biological activity, and pharmacokinetics of TXU (anti-CD7)-pokeweed antiviral protein in chimpanzees and adult patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 291, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Ferens, W.A.; Haruna, J.; Cobbold, R.; Hovde, C.J. Low numbers of intestinal Shiga toxin-producing E. coli correlate with a poor prognosis in sheep infected with bovine leukemia virus. J. Vet. Sci. 2008, 9, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando-Martínez, S.; Ruiz-Mateos, E.; Romero-Sánchez, M.C.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.Á.; Viciana, P.; Genebat, M.; Leal, M. HIV infection-related premature immunosenescence: High rates of immune exhaustion after short time of infection. Curr. HIV Res. 2011, 9, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.; Branch, D.R.; Sakac, D.; Lingwood, C.A.; Siatskas, C.; Robinson, C.J.; Brady, R.O.; Medin, J.A. Lack of susceptibility of cells from patients with fabry disease to infection with R5 human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS 2005, 19, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjes, N.; Binnington, B.; Smith, C.; Maloney, M.; Lingwood, C. Differential tissue targeting and pathogenesis of verotoxins 1 and 2 in the mouse animal model. Kid. Int. 2002, 62, 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramotar, K.; Boyd, B.; Tyrrell, G.; Gariepy, J.; Lingwood, C.; Brunton, J. Characterization of Shiga-like toxin I B subunit purified from overproducing clones of the SLT-I B cistron. Biochem. J. 1990, 272, 805–811. [Google Scholar]

- Head, S.; Karmali, M.; Lingwood, C.A. Preparation of VT1 and VT2 hybrid toxins from their purified dissociated subunits: Evidence for B subunit modulation of A subunit function. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 3617–3621. [Google Scholar]

- Cathala, G.; Savouret, J.F.; Mendez, B.; West, B.L.; Karin, M.; Martial, J.A.; Baxter, J.D. A method for isolation of intact, translationally active ribonucleic acid. DNA 1983, 2, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Kibbe, W.A.; Lin, S.M. lumi: A pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1547–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, G.K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004, 3, le3. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, P.L.; Binnington, B.; Sakac, D.; Katsman, Y.; Ramkumar, S.; Gariepy, J.; Kim, M.; Branch, D.R.; Lingwood, C. Verotoxin A Subunit Protects Lymphocytes and T Cell Lines against X4 HIV Infection in Vitro. Toxins 2012, 4, 1517-1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins4121517

Shi PL, Binnington B, Sakac D, Katsman Y, Ramkumar S, Gariepy J, Kim M, Branch DR, Lingwood C. Verotoxin A Subunit Protects Lymphocytes and T Cell Lines against X4 HIV Infection in Vitro. Toxins. 2012; 4(12):1517-1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins4121517

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Pei Lin, Beth Binnington, Darinka Sakac, Yulia Katsman, Stephanie Ramkumar, Jean Gariepy, Minji Kim, Donald R. Branch, and Clifford Lingwood. 2012. "Verotoxin A Subunit Protects Lymphocytes and T Cell Lines against X4 HIV Infection in Vitro" Toxins 4, no. 12: 1517-1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins4121517