Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1: Friend or Foe to Female Metabolism?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review Section

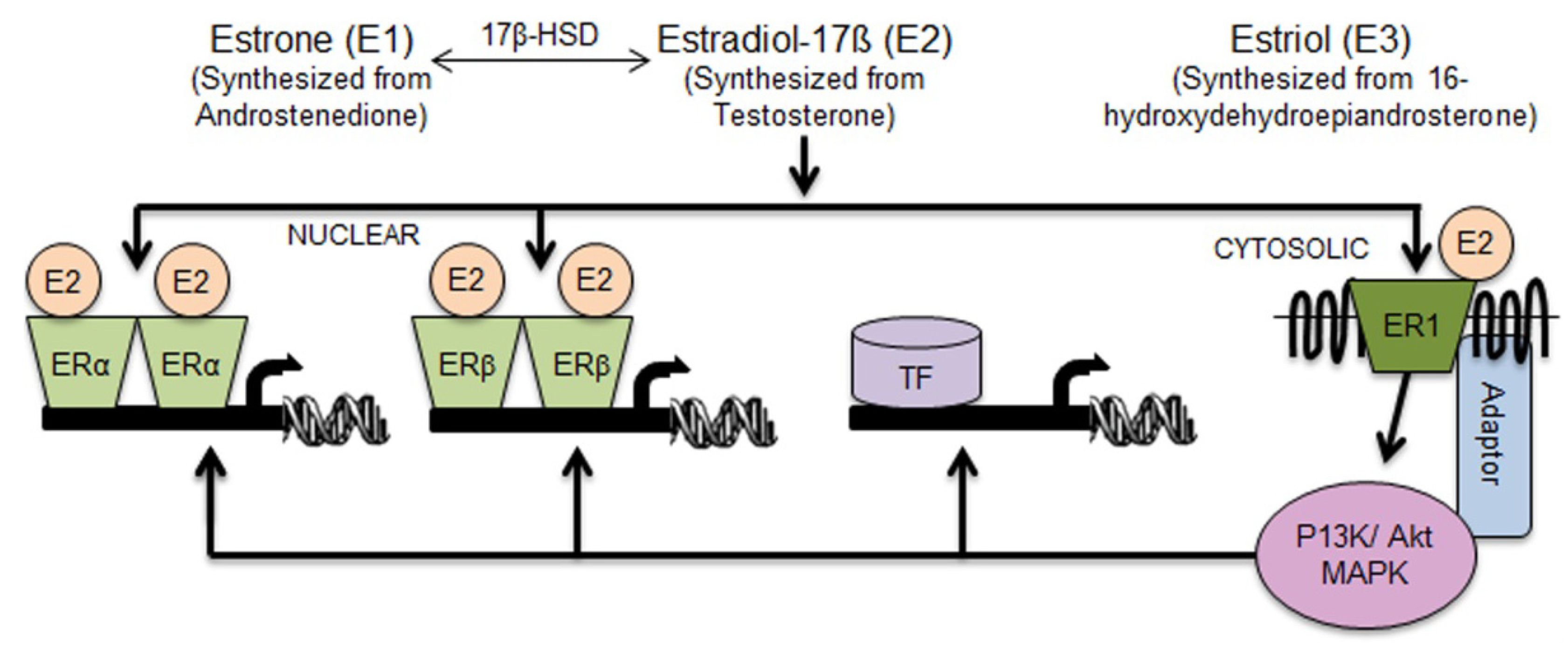

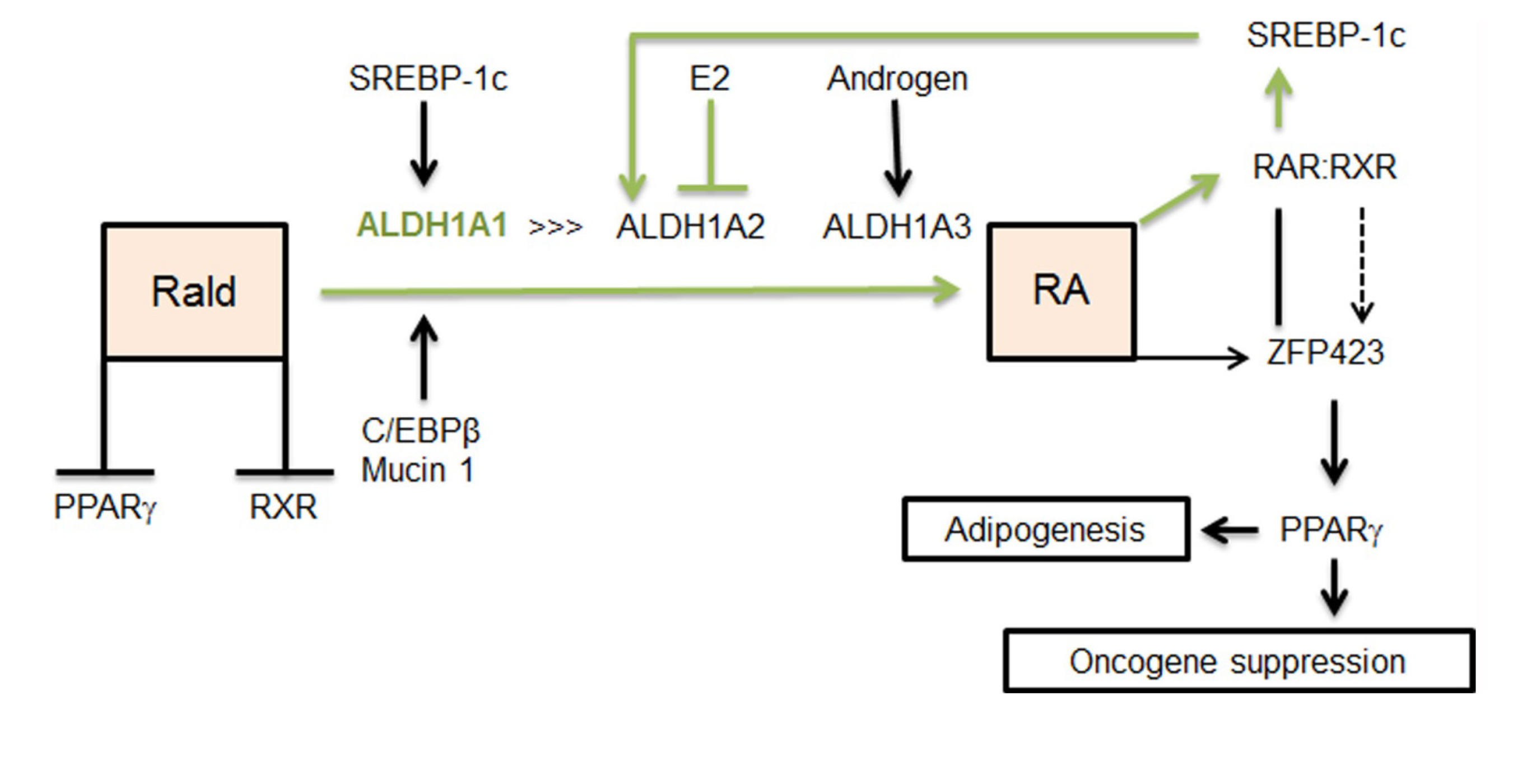

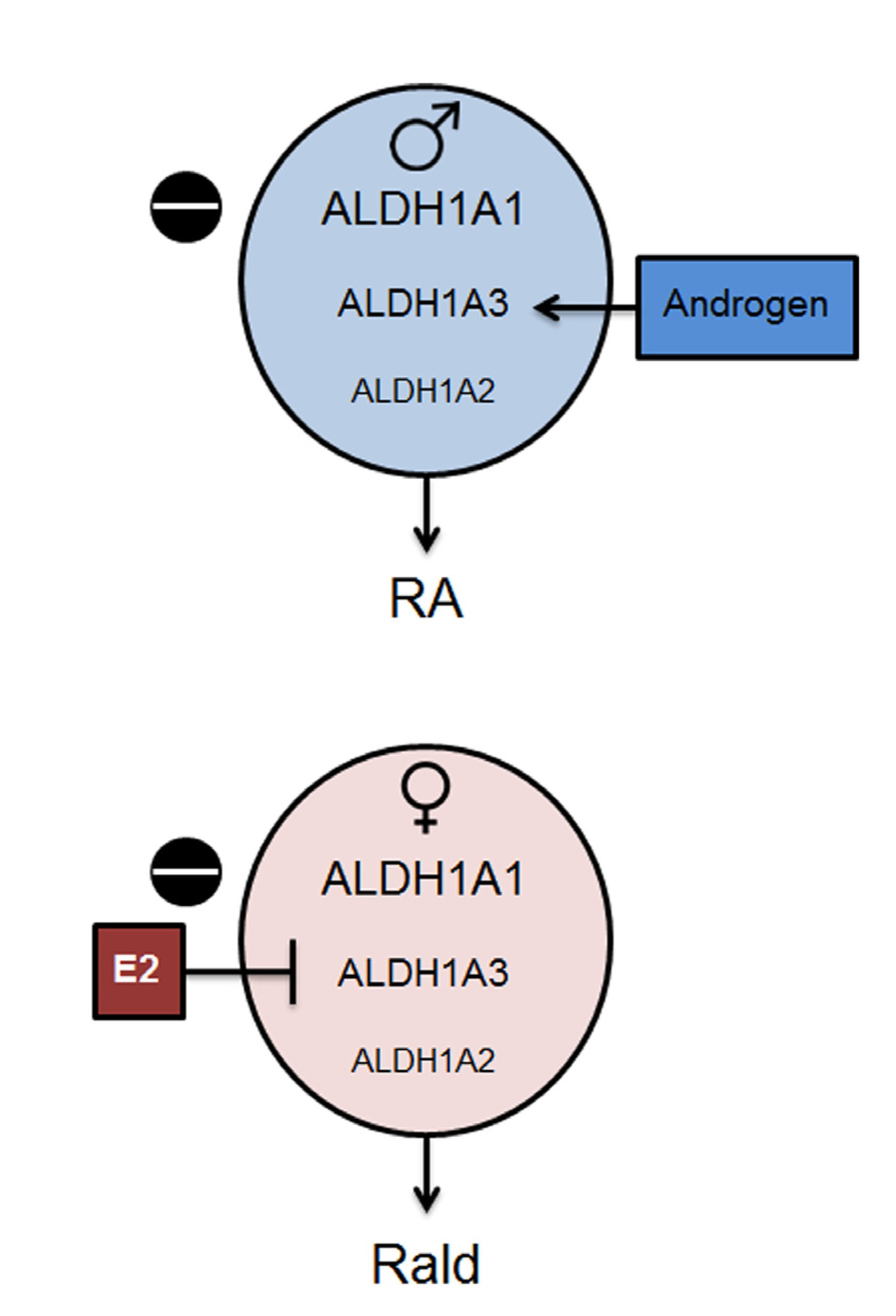

2.1. Aldh1 Family of Enzymes: Function and Regulation by E2

2.2. Aldh1 Regulation of Female-Specific Fat Distribution

2.3. Aldh1 Role in Sex-Specific Diet-Induced Thermogenic Regulation

2.4. Aldh1 Sexual Dimorphism of WAT and Risks for Chronic Diseases

2.5. Aldh1 Control of Sex-Specific Reproduction

3. Conclusions

Perspectives

Abbreviations

| 3β-HSD | 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II enzymes |

| ADH | Alcohol dehydrogenase |

| Adh1 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 1 |

| Aldh1a1−/− | Knockout in Aldh1a1 |

| Aldh1a1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member a1 |

| Aldh1a2 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member a2 |

| Aldh1a3 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member a3 |

| AP-1 | Activator protein 1 |

| ATGL | Adipose triglyceride lipase |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| COX2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| CRABP | Cellular retinoic acid binding protein |

| CYP17 | Cytochrome P450 17 |

| CYP1711A1 | Cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A polypeptide 11 |

| CYP26B1 | Cytochrome P450 26B1 |

| CYP450 | Cytochrome P450 |

| CXC | CXCL Chemokine group of cytokines |

| C/EBPβ | CCAAT/enhancer-binding Protein β |

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| DPP4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 also known as CD26 |

| E1 | Estron |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| E3 | Estriol |

| ERα | Estrogen receptor alpha |

| ERβ | Estrogen receptor beta |

| Erα−/− | Knockout in Erα |

| Erβ−/− | Knockout in Erβ |

| ERE | Estrogen response element |

| FABP | Fatty acid binding protein |

| FSH | Follicle stimulating hormone |

| GATA | GATA-binding factor 1 |

| GPER | G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 |

| HSD3B2 | 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-delta 5-delta 4 isomerase type II |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IFNγ(IFNg) | Interferon gamma |

| IP-10 | Inducible Protein-10 |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PGC | Primordial germ cell |

| PGC-1A (PPARGC1A) | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, gamma, Coactivator 1 alpha |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, Pparg |

| RAR | Retinoic acid receptor, Rara |

| RARE | Retinoic acid response elements |

| Rald | Retinaldehyde, retinal |

| RA | Retinoic acid |

| RoDH | Retinol dehydrogenase |

| ROL | Retinol |

| RXR | Retinoid X receptor |

| SF | Subcutaneous fat |

| SREBP-1c (SREBF1) | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein isoform 1 C |

| STRA8 | Stimulated by retinoic acid 8 |

| STAR | Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| TF | Tissue factor |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

| VF | Visceral fat (in this paper mouse retroperitoneal and human omental) |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| ZFP423 | Zinc-finger transcription factor 423 |

| 5a-r | 5a-Reductase, and 5a-Androstane-3,17-dione |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wittnich, C.; Tan, L.; Wallen, J.; Belanger, M. Sex differences in myocardial metabolism and cardiac function: an emerging concept. Pflug. Arch. 2013, 465, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Wedick, N.M.; Pan, A.; Manson, J.E.; Rexrode, K.M.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B. Quantity and variety in fruit and vegetable intake and risk of coronary heart disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Chaudry, I.H. The effects of estrogen on various organs: Therapeutic approach for sepsis, trauma, and reperfusion injury. Part 2: Liver, intestine, spleen, and kidney. J. Anesth. 2012, 26, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.R.; Clegg, D.J.; Prossnitz, E.R.; Barton, M. Obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes: Sex differences and role of oestrogen receptors. Acta Physiol. 2011, 203, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, R.D.; Hill, R.L.; Vaughan, M. The discovery of estrone, estriol, and estradiol and the biochemical study of reproduction. The work of Edward Adelbert Doisy. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, e17. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, R.P.; Gustafsson, J.A. Estrogen receptors and the metabolic network. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.V. On the mechanism of estrogen action. Perspect. Biol. Med. 1962, 6, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper, G.G.; Enmark, E.; Pelto-Huikko, M.; Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J.A. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5925–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, M.; Castano, E.; Notides, A.C.; Sasson, S. Molecular and kinetic basis for the mixed agonist/antagonist activity of estriol. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997, 11, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krum, S.A.; Miranda-Carboni, G.A.; Lupien, M.; Eeckhoute, J.; Carroll, J.S.; Brown, M. Unique ERalpha cistromes control cell type-specific gene regulation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 2393–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.S.; Meyer, C.A.; Song, J.; Li, W.; Geistlinger, T.R.; Eeckhoute, J.; Brodsky, A.S.; Keeton, E.K.; Fertuck, K.C.; Hall, G.F.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, M.; Eeckhoute, J.; Meyer, C.A.; Krum, S.A.; Rhodes, D.R.; Liu, X.S.; Brown, M. Coactivator function defines the active estrogen receptor alpha cistrome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 3413–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velickovic, K.; Cvoro, A.; Srdic, B.; Stokic, E.; Markelic, M.; Golic, I.; Otasevic, V.; Stancic, A.; Jankovic, A.; Vucetic, M.; et al. Expression and subcellular localization of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in human fetal brown adipose tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooptiwut, S.; Mahawong, P.; Hanchang, W.; Semprasert, N.; Kaewin, S.; Limjindaporn, T.; Yenchitsomanus, P.T. Estrogen reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress to protect against glucotoxicity induced-pancreatic beta-cell death. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 139C, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dulos, J.; Vijn, P.; van Doorn, C.; Hofstra, C.L.; Veening-Griffioen, D.; de Graaf, J.; Dijcks, F.A.; Boots, A.M. Suppression of the inflammatory response in experimental arthritis is mediated via estrogen receptor alpha but not estrogen receptor beta. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, R101. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson, C.; Hellberg, N.; Parini, P.; Vidal, O.; Bohlooly-Y, M.; Rudling, M.; Lindberg, M.K.; Warner, M.; Angelin, B.; Gustafsson, J.A. Obesity and disturbed lipoprotein profile in estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient male mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 278, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, P.A.; Taylor, J.A.; Iwamoto, G.A.; Lubahn, D.B.; Cooke, P.S. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12729–12734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, C.; Lastra, G.; Habibi, J.; Mugerfeld, I.; Garro, M.; Sowers, J.R. Loss of estrogen receptor alpha signaling leads to insulin resistance and obesity in young and adult female mice. Cardiorenal Med. 2012, 2, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riant, E.; Waget, A.; Cogo, H.; Arnal, J.F.; Burcelin, R.; Gourdy, P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2109–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, L.B.; Loo, K.K.; Liu, H.B.; Peterson, C.; Tiwari-Woodruff, S.; Voskuhl, R.R. Treatment with an estrogen receptor alpha ligand is neuroprotective in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 6823–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B.; Loo, K.K.; Palaszynski, K.; Ashouri, J.; Lubahn, D.B.; Voskuhl, R.R. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates estrogen’s immune protection in autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 6936–6940. [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz, E.R.; Barton, M. The G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 7, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushchina, L.V.; Yasmeen, R.; Ziouzenkova, O. Moderate vitamin A supplementation in obese mice regulates tissue factor and cytokine production in a sex-specific manner. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 539, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, B.; Yasmeen, R.; Jeyakumar, S.M.; Yang, F.; Thomou, T.; Alder, H.; Duester, G.; Maiseyeu, A.; Mihai, G.; Harrison, E.H.; et al. Concerted action of aldehyde dehydrogenases influences depot-specific fat formation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 25, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, X.; Maiseyeu, A.; Mihai, G.; Yasmeen, R.; DiSilvestro, D.; Maurya, S.K.; Periasamy, M.; Bergdall, K.V.; Duester, G.; et al. The prolonged survival of fibroblasts with forced lipid catabolism in visceral fat following encapsulation in alginate-poly-l-lysine. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5638–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, R.; Jeyakumar, S.M.; Reichert, B.; Yang, F.; Ziouzenkova, O. The contribution of vitamin A to autocrine regulation of fat depots. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmeen, R.; Reichert, B.; Deiuliis, J.; Yang, F.; Lynch, A.; Meyers, J.; Sharlach, M.; Shin, S.; Volz, K.S.; Green, K.B.; et al. Autocrine function of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 as a determinant of diet- and sex-specific differences in visceral adiposity. Diabetes 2013, 62, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sandell, L.L.; Trainor, P.A.; Koentgen, F.; Duester, G. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases: Retinoid metabolic effects in mouse knockout models. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, J.L. Physiological insights into all-trans-retinoic acid biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.X.; Gallego, O.; Ardèvol, A.; Moro, A.; Domínguez, M.; Alvarez, S.; Alvarez, R.; de Lera, A.R.; Rovira, C.; Fita, I.; et al. Aldo-keto reductases from the AKR1B subfamily: Retinoid specificity and control of cellular retinoic acid levels. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 178, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.E.; Pierzchalski, K.; Butler Tjaden, N.E.; Pang, X.Y.; Trainor, P.A.; Kane, M.A.; Moise, A.R. The retinaldehyde reductase DHRS3 is essential for preventing the formation of excess retinoic acid during embryonic development. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 4877–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duester, G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell 2008, 134, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziouzenkova, O. Vitamin A metabolism: Challenges and perspectives. Vitam. Trace Elem. 2012, 1, e106. [Google Scholar]

- Germain, P.; Chambon, P.; Eichele, G.; Evans, R.M.; Lazar, M.A.; Leid, M.; De Lera, A.R.; Lotan, R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Gronemeyer, H. International Union of Pharmacology. LX. Retinoic acid receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, P.; Chambon, P.; Eichele, G.; Evans, R.M.; Lazar, M.A.; Leid, M.; De Lera, A.R.; Lotan, R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Gronemeyer, H. International Union of Pharmacology. LXIII. Retinoid X receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Arany, Z.; Seale, P.; Mepani, R.J.; Ye, L.; Conroe, H.M.; Roby, Y.A.; Kulaga, H.; Reed, R.R.; Spiegelman, B.M. Transcriptional control of preadipocyte determination by Zfp423. Nature 2010, 464, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziouzenkova, O.; Orasanu, G.; Sharlach, M.; Akiyama, T.E.; Berger, J.P.; Viereck, J.; Hamilton, J.A.; Tang, G.; Dolnikowski, G.G.; Vogel, S. Retinaldehyde represses adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duester, G.; Mic, F.A.; Molotkov, A. Cytosolic retinoid dehydrogenases govern ubiquitous metabolism of retinol to retinaldehyde followed by tissue-specific metabolism to retinoic acid. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2003, 143–144, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sperkova, Z.; Napoli, J.L. Analysis of mouse retinal dehydrogenase type 2 promoter and expression. Genomics 2001, 74, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, M.D.; Tsai, N.P.; Gupta, P.; Wei, L.N. Regulation of retinal dehydrogenases and retinoic acid synthesis by cholesterol metabolites. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3203–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasino, S.E.; Harrison, E.H.; Wang, T.T. Androgen regulation of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A3 (ALDH1A3) in the androgen-responsive human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Exp. Biol. Med. 2007, 232, 762–771. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.H.; Kakkad, B.; Ong, D.E. Estrogen directly induces expression of retinoic acid biosynthetic enzymes, compartmentalized between the epithelium and underlying stromal cells in rat uterus. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4756–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Ahmad, R.; Rajabi, H.; Kharbanda, A.; Kufe, D. MUC1-C oncoprotein activates ERK→C/EBPβ signaling and induction of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 30892–30903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Chen, W.; Howell, M.; Zhang, R.; Chen, G. The hepatic Raldh1 expression is elevated in Zucker fatty rats and its over-expression introduced the retinal-induced Srebp-1c expression in INS-1 cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e45210. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Shimano, H.; Amemiya-Kudo, M.; Yahagi, N.; Hasty, A.H.; Matsuzaka, T.; Okazaki, H.; Tamura, Y.; Iizuka, Y.; Ohashi, K.; et al. Identification of liver X receptor-retinoid X receptor as an activator of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c gene promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 2991–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotkov, A.; Duester, G. Genetic evidence that retinaldehyde dehydrogenase Raldh1 (Aldh1a1) functions downstream of alcohol dehydrogenase Adh1 in metabolism of retinol to retinoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36085–36090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, D.; Visser, M.; Sepulveda, D.; Pierson, R.N.; Harris, T.; Heymsfield, S.B. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fatness across age, sex, and ethnic groups? Am. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 143, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, U.A.; Tchoukalova, Y.D. Sex dimorphism and depot differences in adipose tissue function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ford, E.S.; McGuire, L.C.; Mokdad, A.H. Increasing trends in waist circumference and abdominal obesity among U.S. adults. Obesity 2007, 15, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Empana, J.P.; Ducimetiere, P.; Charles, M.A.; Jouven, X. Sagittal abdominal diameter and risk of sudden death in asymptomatic middle-aged men: The Paris Prospective Study I. Circulation 2004, 110, 2781–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canoy, D.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Wareham, N.; Luben, R.; Welch, A.; Bingham, S.; Buchan, I.; Day, N.; Khaw, K.T. Body fat distribution and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition in Norfolk cohort: A population-based prospective study. Circulation 2007, 116, 2933–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciero, P.J.; Goran, M.I.; Poehlman, E.T. Resting metabolic rate is lower in women than in men. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993, 75, 2514–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Atkinson, S.A.; Phillips, S.M.; MacDougall, J.D. Carbohydrate loading and metabolism during exercise in men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995, 78, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Komi, P.V.; Karlsson, J. Skeletal muscle fibre types, enzyme activities and physical performance in young males and females. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1978, 103, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, A.; Drolet, R.; Noel, S.; Paris, G.; Tchernof, A. Visceral fat accumulation is an indicator of adipose tissue macrophage infiltration in women. Metabolism 2012, 61, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.R.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Greenway, F.; Ryan, D.; deJonge, L.; de la Bretonne, J.; Volafova, J.; Bray, G.A. Contributions of total body fat, abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments, and visceral adipose tissue to the metabolic complications of obesity. Metabolism 2001, 50, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, M.B.; Dekker, J.M.; Visser, M.; Yudkin, J.S.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Bouter, L.M.; Heine, R.J.; Nijpels, G.; Seidell, J.C. Larger thigh and hip circumferences are associated with better glucose tolerance: The Hoorn study. Obes. Res. 2003, 11, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Wang, Z.M.; Ross, R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zillikens, M.C.; Yazdanpanah, M.; Pardo, L.M.; Rivadeneira, F.; Aulchenko, Y.S.; Oostra, B.A.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Pols, H.A.; van Duijn, C.M. Sex-specific genetic effects influence variation in body composition. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 2233–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, K.; Boivin, A.; Tchernof, A. Androgens and body fat distribution. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 108, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Hernandez Mijares, A.; Johnson, C.M.; Jensen, M.D. Postprandial leg and splanchnic fatty acid metabolism in nonobese men and women. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, E965–E972. [Google Scholar]

- Blaak, E. Gender differences in fat metabolism. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2001, 4, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lladó, I.; Rodríguez-Cuenca, S.; Pujol, E.; Monjo, M.; Estrany, M.E.; Roca, P.; Palou, A. Gender effects on adrenergic receptor expression and lipolysis in white adipose tissue of rats. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schousboe, K.; Willemsen, G.; Kyvik, K.O.; Mortensen, J.; Boomsma, D.I.; Cornes, B.K.; Davis, C.J.; Fagnani, C.; Hjelmborg, J.; Kaprio, J.; et al. Sex differences in heritability of BMI: A comparative study of results from twin studies in eight countries. Twin Res. 2003, 6, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Seeley, R.J.; Clegg, D.J. Sexual differences in the control of energy homeostasis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Kahn, C.R. Transplantation of adipose tissue and stem cells: Role in metabolism and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010, 6, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cohen, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adaptive thermogenesis in adipocytes: Is beige the new brown? Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, B.H.; Krishnaswami, S.; Harris, T.B.; Katsiaras, A.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Simonsick, E.M.; Nevitt, M.; Holvoet, P.; Newman, A.B. Obesity, regional body fat distribution, and the metabolic syndrome in older men and women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, J.E.; Heshka, S.; Albu, J.B.; Heymsfield, S.; Gallagher, D. Femoral-gluteal subcutaneous and intermuscular adipose tissues have independent and opposing relationships with CVD risk. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerath, E.W.; Sun, S.S.; Rogers, N.; Lee, M.; Reed, D.; Choh, A.C.; Couch, W.; Czerwinski, S.A.; Chumlea, W.C.; Siervogel, R.M.; et al. Anatomical patterning of visceral adipose tissue: Race, sex, and age variation. Obesity 2007, 15, 2984–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, P.J.; Terry, J.G.; Evans, G.W.; Hinson, W.H.; Crouse, J.R., III; Heiss, G. Sex-specific associations of magnetic resonance imaging-derived intra-abdominal and subcutaneous fat areas with conventional anthropometric indices. The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 144, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camhi, S.M.; Bray, G.A.; Bouchard, C.; Greenway, F.L.; Johnson, W.D.; Newton, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Ryan, D.H.; Smith, S.R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. The relationship of waist circumference and BMI to visceral, subcutaneous, and total body fat: Sex and race differences. Obesity 2011, 19, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchoukalova, Y.D.; Votruba, S.B.; Tchkonia, T.; Giorgadze, N.; Kirkland, J.L.; Jensen, M.D. Regional differences in cellular mechanisms of adipose tissue gain with overfeeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18226–18231. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, C.J.; Lees, B.; Stevenson, J.C. Sex- and menopause-associated changes in body-fat distribution. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 55, 950–954. [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen, O.L.; Hassager, C.; Christiansen, C. Age- and menopause-associated variations in body composition and fat distribution in healthy women as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Metabolism 1995, 44, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, M.J.; Tchernof, A.; Sites, C.K.; Poehlman, E.T. Effect of menopausal status on body composition and abdominal fat distribution. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, J.C.; Champagne, C.M.; de Jonge, L.; Xie, H.; Smith, S.R. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, K.; Tokunaga, K.; Fujioka, S.; Kobatake, T.; Keno, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Shimomura, I.; Tarui, S.; Matsuzawa, Y. Sexual dimorphism of age-related changes in whole-body fat distribution in the obese. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1994, 18, 207–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kanaley, J.A.; Sames, C.; Swisher, L.; Swick, A.G.; Ploutz-Snyder, L.L.; Steppan, C.M.; Sagendorf, K.S.; Feiglin, D.; Jaynes, E.B.; Meyer, R.A.; et al. Abdominal fat distribution in pre- and postmenopausal women: The impact of physical activity, age, and menopausal status. Metabolism 2001, 50, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, G.; Liu, Y.; Capri, O.; Critelli, C.; Barillaro, F.; Galoppi, P.; Zichella, L. Evaluation of the body composition and fat distribution in long-term users of hormone replacement therapy. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1999, 48, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeland, M.A.; Stefanick, M.L.; Kritz-Silverstein, D.; Fineberg, S.E.; Waclawiw, M.A.; James, M.K.; Greendale, G.A. Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on body weight and waist and hip girths. Postmenopausal estrogen-progestin interventions study investigators. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, J.; Derstine, A.; Gower, B.A. Fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women: Influence of hormone replacement. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; San Millan, J.L. Abdominal adiposity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 18, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, V.K.; Dhir, R.; Yin, X.; Ahima, R.S.; Song, W.C. Estrogen sulfotransferase regulates body fat and glucose homeostasis in female mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E657–E664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H.G.; Dudley, E.C.; Robertson, D.M.; Dennerstein, L. Hormonal changes in the menopause transition. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 2002, 57, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkjaer, J.; Tjonneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Sorensen, T.I. Dietary predictors of 5-year changes in waist circumference. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, B.M.; Flier, J.S. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell 2001, 104, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepuru, M.; Eswaraka, J.; Kearbey, J.D.; Barrett, C.M.; Raghow, S.; Veverka, K.A.; Miller, D.D.; Dalton, J.T.; Narayanan, R. Estrogen receptor-β-selective ligands alleviate high-fat diet- and ovariectomy-induced obesity in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31292–31303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Won, Y.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, B.; Kim, E.Y.; Yoon, M.; Oh, G.T. Signal crosstalk between estrogen and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha on adiposity. BMB Rep. 2009, 42, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigserver, P.; Wu, Z.; Park, C.W.; Graves, R.; Wright, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 1998, 92, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haemmerle, G.; Moustafa, T.; Woelkart, G.; Büttner, S.; Schmidt, A.; van de Weijer, T.; Hesselink, M.; Jaeger, D.; Kienesberger, P.C.; Zierler, K.; et al. ATGL-mediated fat catabolism regulates cardiac mitochondrial function via PPAR-alpha and PGC-1. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Abbott, M.J.; Tang, T.; Hudak, C.S.; Kim, Y.; Bruss, M.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Lee, H.Y.; Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I.; et al. Desnutrin/ATGL is regulated by AMPK and is required for a brown adipose phenotype. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, F.W.; Vernochet, C.; O’Brien, P.; Spoerl, S.; Brown, J.D.; Nallamshetty, S.; Zeyda, M.; Stulnig, T.M.; Cohen, D.E.; Kahn, C.R.; et al. Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 regulates a thermogenic program in white adipose tissue. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repa, J.J.; Hanson, K.K.; Clagett-Dame, M. All-trans-retinol is a ligand for the retinoic acid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 7293–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader, J.; Palou, A.; Bonet, M.L. Induction of uncoupling protein-1 in mouse embryonic fibroblast-derived adipocytes by retinoic acid. Obesity 2010, 18, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.B.; Escobar, L.; Tan, P.L.; Muzina, M.; Zwain, S.; Buchanan, C. Live encapsulated porcine islets from a type 1 diabetic patient 9.5 yr after xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation 2007, 14, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, E.B.; Shen, W. Gender differences in insulin resistance, body composition, and energy balance. Gend. Med. 2009, 6, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, S.; Leonardini, A.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F. Biological specificity of visceral adipose tissue and therapeutic intervention. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 114, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuzaki, H.; Paterson, J.; Shinyama, H.; Morton, N.M.; Mullins, J.J.; Seckl, J.R.; Flier, J.S. A transgenic model of visceral obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Science 2001, 294, 2166–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; van de Wall, E.; Laplante, M.; Azzara, A.; Trujillo, M.E.; Hofmann, S.M.; Schraw, T.; Durand, J.L.; Li, H.; Li, G.; et al. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2621–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar Ahmed, S.; Penhale, W.J.; Talal, N. Sex hormones, immune responses, and autoimmune disease. Mechanisms of sex hormone action. Am. J. Pathol. 1985, 121, 531–551. [Google Scholar]

- Bidulescu, A.; Liu, J.; Hickson, D.A.; Hairston, K.G.; Fox, E.R.; Arnett, D.K.; Sumner, A.E.; Taylor, H.A.; Gibbons, G.H. Gender differences in the association of visceral and subcutaneous adiposity with adiponectin in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2013, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turer, A.T.; Scherer, P.E. Adiponectin: Mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2319–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitacre, C.C. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, O.P. Effect of vitamin A deficiency on the immune response in obesity. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Jeong, W.I. Retinoic acids and hepatic stellate cells in liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 27, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, F.W.; Orasanu, G.; Nallamshetty, S.; Brown, J.D.; Wang, H.; Luger, P.; Qi, N.R.; Burant, C.F.; Duester, G.; Plutzky, J. Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 coordinates hepatic gluconeogenesis and lipid metabolism. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3089–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.A.; Folias, A.E.; Pingitore, A.; Perri, M.; Krois, C.R.; Ryu, J.Y.; Cione, E.; Napoli, J.L. CrbpI modulates glucose homeostasis and pancreas 9-cis-retinoic acid concentrations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 3277–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amleh, A.; Smith, L.; Chen, H.; Taketo, T. Both nuclear and cytoplasmic components are defective in oocytes of the B6.Y(TIR) sex-reversed female mouse. Dev. Biol. 2000, 219, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, M.W. Functional capacity of sex-reversed (XX, Sxr/+) mouse germ cells as shown by progeny derived from XX, Sxr/+ oocytes of a female chimera. J. Exp. Zool. 1983, 226, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, P.S. The role of the mammalian Y chromosome in spermatogenesis. Development 1987, 101, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, A. The fate of germ cells in the testis of fetal Sex-reversed mice. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1981, 61, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, A. Germ cells and germ cell sex. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1995, 350, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.P.; Ford, C.E.; Lyon, M.F. Direct evidence of the capacity of the XY germ cell in the mouse to become an oocyte. Nature 1977, 267, 430–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.J.; Burgoyne, P.S. In situ analysis of fetal, prepuberal and adult XX↔XY chimaeric mouse testes: Sertoli cells are predominantly, but not exclusively, XY. Development 1991, 112, 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Oulad-Abdelghani, M.; Bouillet, P.; Décimo, D.; Gansmuller, A.; Heyberger, S.; Dollé, P.; Bronner, S.; Lutz, Y.; Chambon, P. Characterization of a premeiotic germ cell-specific cytoplasmic protein encoded by Stra8, a novel retinoic acid-responsive gene. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 135, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, M.; La Sala, G.; Barbagallo, F.; De Felici, M.; Farini, D. STRA8 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm and displays transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 35781–35793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Nie, R.; Friel, P.; Mitchell, D.; Evanoff, R.M.; Pouchnik, D.; Banasik, B.; McCarrey, J.R.; Small, C.; et al. Expression of stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8) and maturation of murine gonocytes and spermatogonia induced by retinoic acid in vitro. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 78, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Cunningham, T.J.; Duester, G. Resolving molecular events in the regulation of meiosis in male and female germ cells. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pe25. [Google Scholar]

- Krentz, A.D.; Murphy, M.W.; Sarver, A.L.; Griswold, M.D.; Bardwell, V.J.; Zarkower, D. DMRT1 promotes oogenesis by transcriptional activation of Stra8 in the mammalian fetal ovary. Dev. Biol. 2011, 356, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naillat, F.; Prunskaite-Hyyryläinen, R.; Pietilä, I.; Sormunen, R.; Jokela, T.; Shan, J.; Vainio, S.J. Wnt4/5a signalling coordinates cell adhesion and entry into meiosis during presumptive ovarian follicle development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J.; Feng, C.W.; Spiller, C.; Davidson, T.L.; Jackson, A.; Koopman, P. FGF9 suppresses meiosis and promotes male germ cell fate in mice. Dev. Cell. 2010, 19, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J.; Knight, D.; Smith, C.; Wilhelm, D.; Richman, J.; Mamiya, S.; Yashiro, K.; Chawengsaksophak, K.; Wilson, M.J.; Rossant, J.; et al. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science 2006, 312, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubova, J.; Menke, D.B.; Zhou, Q.; Capel, B.; Griswold, M.D.; Page, D.C. Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2474–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bouffant, R.; Guerquin, M.J.; Duquenne, C.; Frydman, N.; Coffigny, H.; Rouiller-Fabre, V.; Frydman, R.; Habert, R.; Livera, G. Meiosis initiation in the human ovary requires intrinsic retinoic acid synthesis. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzoros, C.S. Leptin in relation to the lipodystrophy-associated metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. J. 2012, 36, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, R.; Meyers, J.M.; Alvarez, C.E.; Thomas, J.L.; Bonnegarde-Bernard, A.; Alder, H.; Papenfuss, T.L.; Benson, D.M., Jr.; Boyaka, P.N.; Ziouzenkova, O. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-1a1 induces oncogene suppressor genes in B cell populations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 3218–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R.; Woods, K.S.; Reyna, R.; Key, T.J.; Knochenhauer, E.S.; Yildiz, B.O. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2745–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuncion, M.; Calvo, R.M.; San Millan, J.L.; Sancho, J.; Avila, S.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. A prospective study of the prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected Caucasian women from Spain. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 2434–2438. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.J. A practical approach to the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovall, D.W.; Bailey, A.P.; Pastore, L.M. Assessment of insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Women’s Health 2011, 20, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, J.M.; Calle, E.E.; Rodriguez, C.; Thun, M.J. Body mass index, height, and postmenopausal breast cancer mortality in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer Causes Control 2002, 13, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfoss, B.L.; Holmqvist, B.; Jernstrom, H.; Alm, P.; Olsson, H. Women with familial risk for breast cancer have an increased frequency of aldehyde dehydrogenase expressing cells in breast ductules. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2013, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickenheisser, J.K.; Nelson-DeGrave, V.L.; Hendricks, K.L.; Legro, R.S.; Strauss, J.F., III; McAllister, J.M. Retinoids and retinol differentially regulate steroid biosynthesis in ovarian theca cells isolated from normal cycling women and women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4858–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, D.S.; Kisslo, J. Health Care Financing Administration release of final physician payment reform regulation. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 1992, 5, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Magoffin, D.A. Ovarian enzyme activities in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86, S9–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.R.; Nelson, V.L.; Ho, C.; Jansen, E.; Wang, C.Y.; Urbanek, M.; McAllister, J.M.; Mosselman, S.; Strauss, J.F., III. The molecular phenotype of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) theca cells and new candidate PCOS genes defined by microarray analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 26380–26390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladek, N.E.; Dockham, P.A.; Lee, M.O. Human and mouse hepatic aldehyde dehydrogenases important in the biotransformation of cyclophosphamide and the retinoids. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1991, 284, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, M.; Karasawa, H.; Sakakibara, S.; Shinagawa, A. Raldh3 expression in diabetic islets reciprocally regulates secretion of insulin and glucagon from pancreatic islets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 401, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladek, N.E. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-mediated cellular relative insensitivity to the oxazaphosphorines. Curr. Pharm. Des. 1999, 5, 607–625. [Google Scholar]

- Collard, F.; Vertommen, D.; Fortpied, J.; Duester, G.; van Schaftingen, E. Identification of 3-deoxyglucosone dehydrogenase as aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1). Biochimie 2007, 89, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrosino, J.M.; DiSilvestro, D.; Ziouzenkova, O. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1: Friend or Foe to Female Metabolism? Nutrients 2014, 6, 950-973. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6030950

Petrosino JM, DiSilvestro D, Ziouzenkova O. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1: Friend or Foe to Female Metabolism? Nutrients. 2014; 6(3):950-973. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6030950

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrosino, Jennifer M., David DiSilvestro, and Ouliana Ziouzenkova. 2014. "Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1: Friend or Foe to Female Metabolism?" Nutrients 6, no. 3: 950-973. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6030950

APA StylePetrosino, J. M., DiSilvestro, D., & Ziouzenkova, O. (2014). Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1: Friend or Foe to Female Metabolism? Nutrients, 6(3), 950-973. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6030950