Iron Absorption in Drosophila melanogaster

Abstract

:1. Introduction

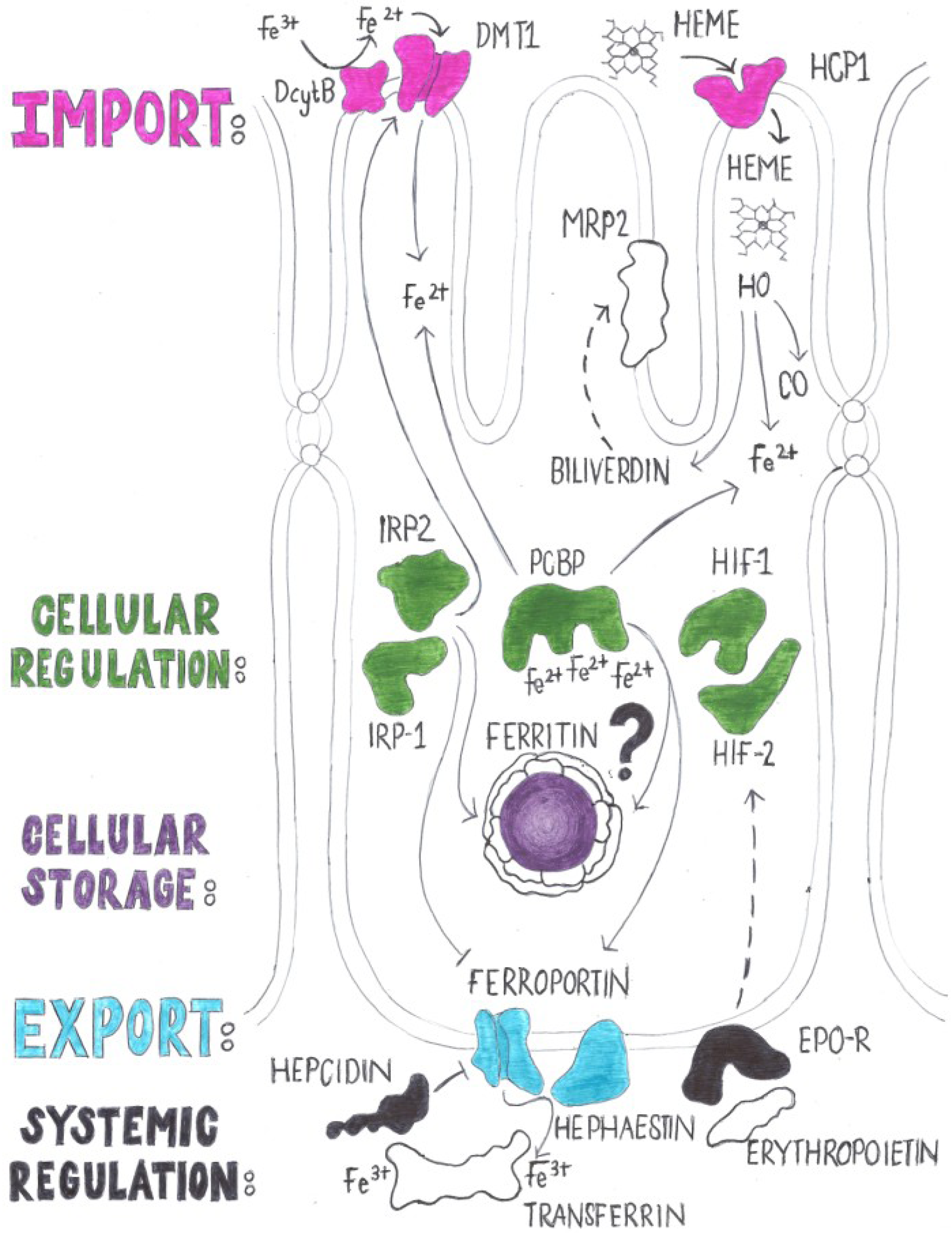

2. Brief Overview of Iron Absorption in Mammals

2.1. Iron Trafficking through the Enterocyte

2.2. Regulation of Iron Absorption

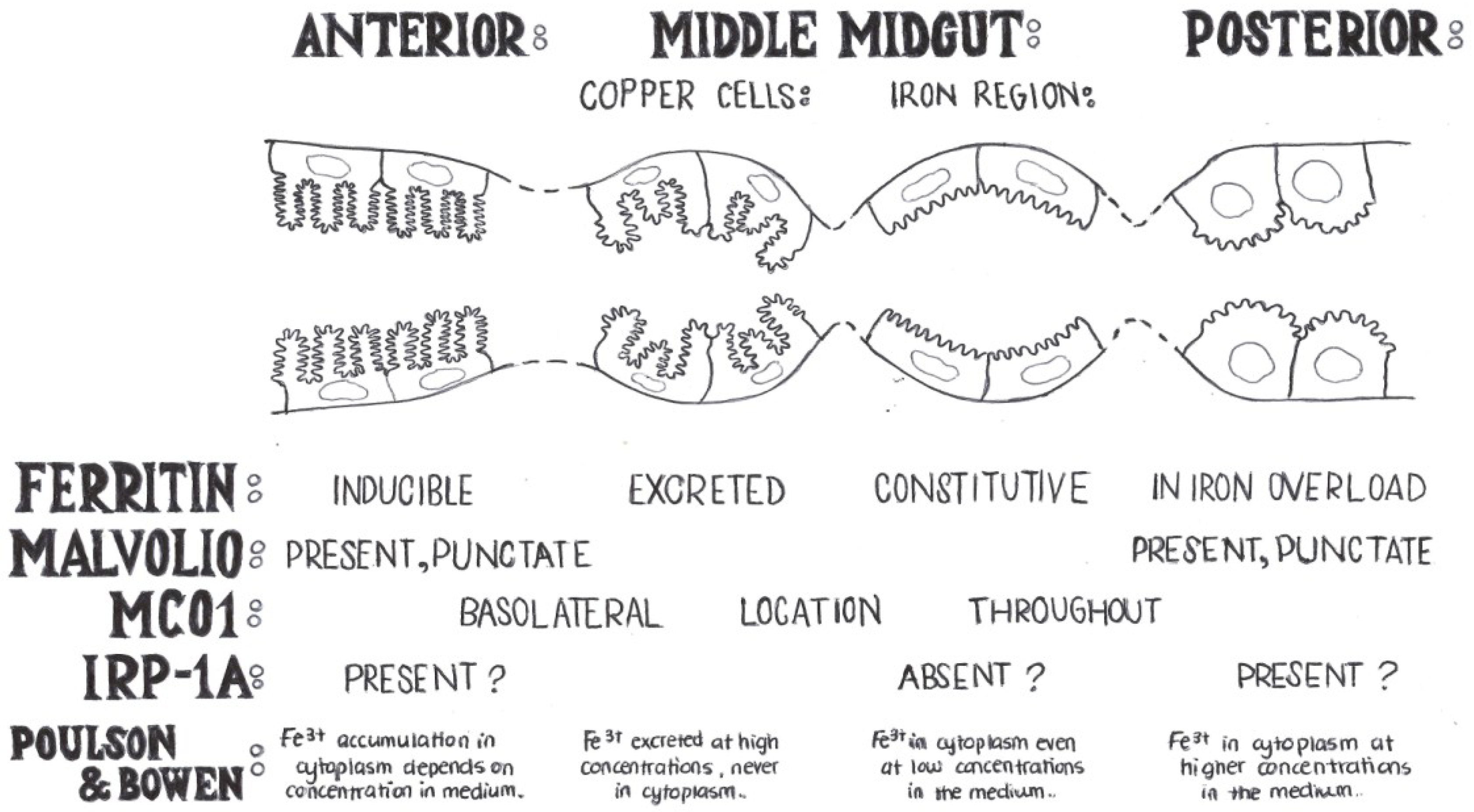

3. Early Studies of Iron Homeostasis in Drosophila

4. Genes with a Known Function in Iron Absorption in Drosophila melanogaster

| Protein name (mammals) | Protein name (Drosophila) | Key role | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMT1 | Malvolio | Malvolio mutants are iron deficient and show behavioral defects. | [66,70,72,73] |

| Ferritin | Ferritin | Drosophila ferritin is a secreted protein required for iron storage and also iron absorption. | [2,15,54,62,63,74,75,76] |

| Transferrin | Tsf1 | Tsf1 is an immune-responsive gene. Whether it traffics iron between cells remains unclear. | [53,55,64,77,78] |

| Melanotransferrin | Tsf2 | Tsf2 is required for the assembly of septate junctions in epithelial cells. | [67] |

| Hephaestin | MCO1, MCO3 | MCO1 and MCO3 are putative ferroxidases. Both show loss-of-function phenotypes with respect to iron homeostasis. | [70,71] |

| IRP1, IRP2 | IRP-1A | IRP-1A regulates ferritin and succinate dehydrogenase translation via IREs. | [61,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

4.1. Mvl, the Drosophila Homolog of DMT-1

4.2. Ferritin

4.3. MCOs

4.4. Transferrins

4.5. IRP/IRE

5. Genes with a Known Function in Iron Absorption in Mammals that Are Conserved but Have Not Been Studied in Drosophila melanogaster

| Protein name (mammals) | Putative homologous genes in Drosophila | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dcytb | CG1275; nemy | One of two fly homologs (nemy) has a function in learning and memory. | [91,92] |

| HCP1 | CG30345 | Flybase reports low levels of expression for this gene possibly involved in cellular heme uptake. | [93] |

| FLVCR | CG1358 | Flybase reports low levels of expression for this gene possibly involved in cellular heme export. RNAi in clock neurons caused disrupted circadian rhythms. | [93,94] |

| HO1, HO2 | HO | HO is required for development; it degrades but is not inducible by heme. | [95,96] |

| HIFα, HIFβ | sima; tango | HIF signaling is conserved in Drosophila but not studied in the context of iron. | [97,98,99,100,101,102] |

5.1. Dcytb Homologs

5.2. HCP1 Homolog

5.3. FLVCR Homolog

5.4. Heme Oxygenase

5.5. HIF

6. Differences in Iron Homeostasis between Mammals and Insects

| Protein name (mammals) | Key questions arising |

|---|---|

| Ferroportin | How do insects export iron from cells? |

| Hepcidin | How do insects signal peripheral iron sufficiency? |

| Erythropoietin | No erythropoiesis in insects; is there a diffusible signal for systemic hypoxia? |

| Transferrin Receptor | Is there a functional TsfR in flies? What is the function of Tsf1? |

| Is there a ferritin receptor and does ferritin mediate systemic iron transport? |

6.1. Ferroportin

6.2. Hepcidin

6.3. Erythropoietin

6.4. Transferrin Receptor

7. Functional Requirements of Iron in Drosophila

| General process | Specific function | References |

|---|---|---|

| Development | Epithelial junction formation | [67] |

| Spermatogenesis | [131] | |

| Cell proliferation | [135,136] | |

| Ventral furrow formation | [77] | |

| Immune Response | Hemolymph ferritin and transferrin respond to infection | [64,78] |

| Zygomycosis | [137] | |

| Wolbachia | [138,139] | |

| Sindbis viral entry | [140] | |

| Heat Shock Response | Unknown (ferritin and transferrin are heat shock inducible) | [141,142,143] |

| Behavior | Taste perception | [63,69] |

| Circadian Rhythm | [94] | |

| Human Disease Models | Friedreich’s Ataxia | [9,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151] |

| Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease | [152,153,154,155] | |

| Restless Legs Syndrome | [156,157] | |

| Neurodegeneration | [158,159,160,161] |

7.1. Iron Requirements for the Development of Drosophila melanogaster

7.2. Iron and the Immune Response

7.3. Iron and the Heat-Shock Response

7.4. Iron Influences the Behavior of Drosophila melanogaster

7.5. Iron and Models of Human Disease

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Law, J.H. Insects, oxygen, and iron. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 292, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missirlis, F.; Kosmidis, S.; Brody, T.; Mavrakis, M.; Holmberg, S.; Odenwald, W.F.; Skoulakis, E.M.; Rouault, T.A. Homeostatic mechanisms for iron storage revealed by genetic manipulations and live imaging of Drosophila ferritin. Genetics 2007, 177, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. Iron, the oxygen-carrier of respiration-ferment. Science 1925, 61, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N.C.; Eliasson, R.; Reichard, P.; Thelander, L. Nonheme iron as a cofactor in ribonucleotide reductase from E. coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1968, 30, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.V. Molecular and genetic analyses of Drosophila Prat, which encodes the first enzyme of de novo purine biosynthesis. Genetics 1994, 136, 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, V.M.; Marques, G.; Delbecque, J.P.; Kobayashi, K.; Hollingsworth, M.; Burr, J.; Natzle, J.E.; O’Connor, M.B. The Drosophila disembodied gene controls late embryonic morphogenesis and codes for a cytochrome P450 enzyme that regulates embryonic ecdysone levels. Development 2000, 127, 4115–4126. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J.T.; Petryk, A.; Marques, G.; Jarcho, M.; Parvy, J.P.; Dauphin-Villemant, C.; O’Connor, M.B.; Gilbert, L.I. Molecular and biochemical characterization of two P450 enzymes in the ecdysteroidogenic pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11043–11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.K.; Vassort, C.; Brennan, B.A.; Que, L., Jr.; Haavik, J.; Flatmark, T.; Gros, F.; Thibault, J. Purification and characterization of the blue-green rat phaeochromocytoma (PC12) tyrosine hydroxylase with a dopamine-Fe(III) complex. Reversal of the endogenous feedback inhibition by phosphorylation of serine-40. Biochem. J. 1992, 284, 687–695. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J.A.; Ohmann, E.; Sanchez, D.; Botella, J.A.; Liebisch, G.; Molto, M.D.; Ganfornina, M.D.; Schmitz, G.; Schneuwly, S. Altered lipid metabolism in a Drosophila model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 2828–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lill, R.; Hoffmann, B.; Molik, S.; Pierik, A.J.; Rietzschel, N.; Stehling, O.; Uzarska, M.A.; Webert, H.; Wilbrecht, C.; Muhlenhoff, U. The role of mitochondria in cellular iron-sulfur protein biogenesis and iron metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar]

- Pantopoulos, K.; Hentze, M.W. Rapid responses to oxidative stress mediated by iron regulatory protein. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 2917–2924. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, P.; Mole, D.R.; Tian, Y.M.; Wilson, M.I.; Gielbert, J.; Gaskell, S.J.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Hebestreit, H.F.; Mukherji, M.; Schofield, C.J.; et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missirlis, F.; Hu, J.; Kirby, K.; Hilliker, A.J.; Rouault, T.A.; Phillips, J.P. Compartment-specific protection of iron-sulfur proteins by superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 47365–47369. [Google Scholar]

- Sheftel, A.D.; Mason, A.B.; Ponka, P. The long history of iron in the Universe and in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A.; Deshpande, A.; Bettedi, L.; Missirlis, F. Ferritin accumulation under iron scarcity in Drosophila iron cells. Biochimie 2009, 91, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, M.D. Iron-sensing proteins that regulate hepcidin and enteric iron absorption. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 30, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulson, D.F.; Bowen, V.T. Organization and function of the inorganic constituents of nuclei. Exp. Cell Res. 1952, 2, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Massie, H.R.; Aiello, V.R.; Williams, T.R. Iron accumulation during development and ageing of Drosophila. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1985, 29, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, M.; Leung, H. The induction and distribution of an insect ferritin—A new function for the endoplasmic reticulum. Tissue Cell 1984, 16, 739–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.A. Intestinal iron absorption: Regulation by dietary & systemic factors. International journal for vitamin and nutrition research. J. Int. Vitam. Nutr. 2010, 80, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuqua, B.K.; Vulpe, C.D.; Anderson, G.J. Intestinal iron absorption. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2012, 26, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evstatiev, R.; Gasche, C. Iron sensing and signalling. Gut 2012, 61, 933–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantopoulos, K.; Porwal, S.K.; Tartakoff, A.; Devireddy, L. Mechanisms of mammalian iron homeostasis. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 5705–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, D.; Cruchaud, A. On the kinetics of iron absorption in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 1962, 41, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miret, S.; Simpson, R.J.; McKie, A.T. Physiology and molecular biology of dietary iron absorption. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2003, 23, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunshin, H.; Mackenzie, B.; Berger, U.V.; Gunshin, Y.; Romero, M.F.; Boron, W.F.; Nussberger, S.; Gollan, J.L.; Hediger, M.A. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 1997, 388, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKie, A.T.; Barrow, D.; Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Rolfs, A.; Sager, G.; Mudaly, E.; Mudaly, M.; Richardson, C.; Barlow, D.; Bomford, A.; et al. An iron-regulated ferric reductase associated with the absorption of dietary iron. Science 2001, 291, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, M.; Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Oakhill, J.S.; Laftah, A.H.; Takeuchi, K.; Halliday, N.; Khan, Y.; Warley, A.; McCann, F.E.; Hider, R.C.; et al. Identification of an intestinal heme transporter. Cell 2005, 122, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, A.; Jansen, M.; Sakaris, A.; Min, S.H.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Tsai, E.; Sandoval, C.; Zhao, R.; Akabas, M.H.; Goldman, I.D. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell 2006, 127, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, S.B.; Woo, C.H.; Roost, K.T.; Price, D.C.; Schmid, R. Intestinal absorption of hemoglobin iron-heme cleavage by mucosal heme oxygenase. J. Clin. Investig. 1974, 54, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottino, A.D.; Hoffman, T.; Jennes, L.; Vore, M. Expression and localization of multidrug resistant protein mrp2 in rat small intestine. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2000, 293, 717–723. [Google Scholar]

- Jedlitschky, G.; Leier, I.; Buchholz, U.; Hummel-Eisenbeiss, J.; Burchell, B.; Keppler, D. ATP-dependent transport of bilirubin glucuronides by the multidrug resistance protein MRP1 and its hepatocyte canalicular isoform MRP2. Biochem. J. 1997, 327, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Bencze, K.Z.; Stemmler, T.L.; Philpott, C.C. A cytosolic iron chaperone that delivers iron to ferritin. Science 2008, 320, 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanoaica, L.; Darshan, D.; Richman, L.; Schumann, K.; Kuhn, L.C. Intestinal ferritin H is required for an accurate control of iron absorption. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.; Brownlie, A.; Zhou, Y.; Shepard, J.; Pratt, S.J.; Moynihan, J.; Paw, B.H.; Drejer, A.; Barut, B.; Zapata, A.; et al. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature 2000, 403, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulpe, C.D.; Kuo, Y.M.; Murphy, T.L.; Cowley, L.; Askwith, C.; Libina, N.; Gitschier, J.; Anderson, G.J. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen, P. The transferrin receptor and the release of iron from transferrin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1994, 356, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.L. The copper-iron chronicles: The story of an intimate relationship. Biometals 2003, 16, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galy, B.; Ferring-Appel, D.; Kaden, S.; Grone, H.J.; Hentze, M.W. Iron regulatory proteins are essential for intestinal function and control key iron absorption molecules in the duodenum. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pantopoulos, K. Regulation of cellular iron metabolism. Biochem. J. 2011, 434, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyron-Holtz, E.G.; Ghosh, M.C.; Rouault, T.A. Mammalian tissue oxygen levels modulate iron-regulatory protein activities in vivo. Science 2004, 306, 2087–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiannaki, M.; Matak, P.; Keith, B.; Simon, M.C.; Vaulont, S.; Peyssonnaux, C. HIF-2alpha, but not HIF-1alpha, promotes iron absorption in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.A.; Nizzi, C.P.; Chang, Y.I.; Deck, K.M.; Schmidt, P.J.; Galy, B.; Damnernsawad, A.; Broman, A.T.; Kendziorski, C.; Hentze, M.W.; et al. The IRP1-HIF-2alpha axis coordinates iron and oxygen sensing with erythropoiesis and iron absorption. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kovtunovych, G.; Ollivierre-Wilson, H.; Noguchi, A.; Tu, T.; Senecal, T.; Robinson, G.; Crooks, D.R.; et al. Deletion of iron regulatory protein 1 causes polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in mice through translational derepression of HIF2alpha. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.M.; Matsubara, T.; Ito, S.; Yim, S.H.; Gonzalez, F.J. Intestinal hypoxia-inducible transcription factors are essential for iron absorption following iron deficiency. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, V.H. Hypoxic regulation of erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2010, 299, F1–F13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.N.; Chang, Y.Z.; Wang, S.M.; Zhai, X.L.; Shang, J.X.; Li, L.X.; Duan, X.L. Effect of erythropoietin on hepcidin, DMT1 with IRE, and hephaestin gene expression in duodenum of rats. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srai, S.K.; Chung, B.; Marks, J.; Pourvali, K.; Solanky, N.; Rapisarda, C.; Chaston, T.B.; Hanif, R.; Unwin, R.J.; Debnam, E.S.; Sharp, P.A. Erythropoietin regulates intestinal iron absorption in a rat model of chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, H.; Law, J.H. Iron economy in insects: Transport, metabolism, and storage. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1992, 37, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, H.; Law, J.H.; Winzerling, J.J. Iron metabolism in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002, 47, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkov, B.; Georgieva, T. Insect iron binding proteins: Insights from the genomes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 36, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.Q.; Winzerling, J.J. Insect ferritins: Typical or atypical? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1800, 824–833. [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, D.L.; Winzerling, J.J. Insect transferrins: Multifunctional proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, H.; Locke, M. The localization of ferritin in insects. Tissue Cell 1990, 22, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, S.; Tripathi, S. Epithelial ultrastructure and cellular mechanisms of acid and base transport in the Drosophila midgut. J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 212, 1731–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.; Sabaratnam, N.; Aktar, R.; Bettedi, L.; Mandilaras, K.; Missirlis, F. Zinc accumulation in heterozygous mutants of fumble, the pantothenate kinase homologue of Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2942–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanesyan, L.; Gunther, V.; Celniker, S.E.; Georgiev, O.; Schaffner, W. Characterization of MtnE, the fifth metallothionein member in Drosophila. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 16, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massie, H.R.; Aiello, V.R.; Williams, T.R. Inhibition of iron absorption prolongs the life span of Drosophila. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1993, 67, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberger, S.; Mullner, E.W.; Kuhn, L.C. The mRNA-binding protein which controls ferritin and transferrin receptor expression is conserved during evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, A.; Georgieva, T.; Gospodov, I.; Law, J.H.; Dunkov, B.C.; Ralcheva, N.; Barillas-Mury, C.; Ralchev, K.; Kafatos, F.C. Isolation and properties of Drosophila melanogaster ferritin—Molecular cloning of a cDNA that encodes one subunit, and localization of the gene on the third chromosome. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 247, 470–475. [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva, T.; Dunkov, B.C.; Dimov, S.; Ralchev, K.; Law, J.H. Drosophila melanogaster ferritin: cDNA encoding a light chain homologue, temporal and tissue specific expression of both subunit types. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 32, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiga, T.; Georgieva, T.; Dunkov, B.C.; Harizanova, N.; Ralchev, K.; Law, J.H. Drosophila melanogaster transferrin. Cloning, deduced protein sequence, expression during the life cycle, gene localization and up-regulation on bacterial infection. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 260, 414–420. [Google Scholar]

- Muckenthaler, M.; Gunkel, N.; Frishman, D.; Cyrklaff, A.; Tomancak, P.; Hentze, M.W. Iron-regulatory protein-1 (IRP-1) is highly conserved in two invertebrate species—Characterization of IRP-1 homologues in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 254, 230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, V.; Cheah, P.Y.; Ray, K.; Chia, W. Malvolio, the Drosophila homologue of mouse NRAMP-1 (Bcg), is expressed in macrophages and in the nervous system and is required for normal taste behaviour. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 3007–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Tiklova, K.; Senti, K.A.; Wang, S.; Graslund, A.; Samakovlis, C. Epithelial septate junction assembly relies on melanotransferrin iron binding and endocytosis in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.D.; Celniker, S.E.; Holt, R.A.; Evans, C.A.; Gocayne, J.D.; Amanatides, P.G.; Scherer, S.E.; Li, P.W.; Hoskins, R.A.; Galle, R.F.; et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 2000, 287, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missirlis, F.; Holmberg, S.; Georgieva, T.; Dunkov, B.C.; Rouault, T.A.; Law, J.H. Characterization of mitochondrial ferritin in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5893–5898. [Google Scholar]

- Bettedi, L.; Aslam, M.F.; Szular, J.; Mandilaras, K.; Missirlis, F. Iron depletion in the intestines of Malvolio mutant flies does not occur in the absence of a multicopper oxidase. J. Exp. Biol. 2011, 214, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Braun, C.L.; Kanost, M.R.; Gorman, M.J. Multicopper oxidase-1 is a ferroxidase essential for iron homeostasis in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13337–13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgad, S.; Nelson, H.; Segal, D.; Nelson, N. Metal ions suppress the abnormal taste behavior of the Drosophila mutant malvolio. J. Exp. Biol. 1998, 201, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Folwell, J.L.; Barton, C.H.; Shepherd, D. Immunolocalisation of the D. melanogaster Nramp homologue Malvolio to gut and Malpighian tubules provides evidence that Malvolio and Nramp2 are orthologous. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 1988–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhou, B. Ferritin is the key to dietary iron absorption and tissue iron detoxification in Drosophila melanogaster. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkov, B.C.; Georgieva, T. Organization of the ferritin genes in Drosophila melanogaster. DNA Cell Biol. 1999, 18, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, A.E.; West, A.P., Jr.; Hamburger, Z.A.; Hamburger, P.; Bjorkman, P.J. Crystal structure of a secreted insect ferritin reveals a symmetrical arrangement of heavy and light chains. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 349, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, M.; Goyal, A.; Senutovich, N.; Dowd, S.R.; Minden, J.S. Building proteomic pathways using Drosophila ventral furrow formation as a model. Mol. Biosyst. 2008, 4, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, F.; Bulet, P.; Ehret-Sabatier, L. Proteomic analysis of the systemic immune response of Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2004, 3, 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, S.A.; Henderson, B.R.; Kuhn, L.C. Succinate dehydrogenase b mRNA of Drosophila melanogaster has a functional iron-responsive element in its 5′-untranslated region. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 30781–30786. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, N.K.; Pantopoulos, K.; Dandekar, T.; Ackrell, B.A.; Hentze, M.W. Translational regulation of mammalian and Drosophila citric acid cycle enzymes via iron-responsive elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 4925–4930. [Google Scholar]

- Melefors, O. Translational regulation in vivo of the Drosophila melanogaster mRNA encoding succinate dehydrogenase iron protein via iron responsive elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 221, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.I.; Ekengren, S.; Melefors, O.; Soderhall, K. Drosophila ferritin mRNA: Alternative RNA splicing regulates the presence of the iron-responsive element. FEBS Lett. 1998, 436, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, T.; Dunkov, B.C.; Harizanova, N.; Ralchev, K.; Law, J.H. Iron availability dramatically alters the distribution of ferritin subunit messages in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2716–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.F.; Lind, M.I.; Wieslander, L.; Landegren, U.; Soderhall, K.; Melefors, O. Using PRINS for gene mapping in polytene chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 1997, 5, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli, P.; Samuelsson, T. Evolution of the iron-responsive element. RNA 2007, 13, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.I.; Missirlis, F.; Melefors, O.; Uhrigshardt, H.; Kirby, K.; Phillips, J.P.; Soderhall, K.; Rouault, T.A. Of two cytosolic aconitases expressed in Drosophila, only one functions as an iron-regulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 18707–18714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southon, A.; Farlow, A.; Norgate, M.; Burke, R.; Camakaris, J. Malvolio is a copper transporter in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 211, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmer, N.T.; Kanost, M.R. Insect multicopper oxidases: Diversity, properties, and physiological roles. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 40, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryo Rahmanto, Y.; Bal, S.; Loh, K.H.; Richardson, D.R. Melanotransferrin: Search for a function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Uhrigshardt, H.; Rouault, T.A.; Missirlis, F. Insertion mutants in Drosophila melanogaster Hsc20 halt larval growth and lead to reduced iron-sulfur cluster enzyme activities and impaired iron homeostasis. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 18, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyshev, N.G.; Iliadi, K.G.; Bragina, J.V.; Kamysheva, E.A.; Tokmatcheva, E.V.; Preat, T.; Savvateeva-Popova, E.V. Novel memory mutants in Drosophila: Behavioral characteristics of the mutant nemyP153. BMC Neurosci. 2002, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadi, K.G.; Avivi, A.; Iliadi, N.N.; Knight, D.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E.; Taylor, P.; Moran, M.F.; Kamyshev, N.G.; Boulianne, G.L. Nemy encodes a cytochrome b561 that is required for Drosophila learning and memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19986–19991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveley, B.R.; Brooks, A.N.; Carlson, J.W.; Duff, M.O.; Landolin, J.M.; Yang, L.; Artieri, C.G.; van Baren, M.J.; Boley, N.; Booth, B.W.; et al. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 2011, 471, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandilaras, K.; Missirlis, F. Genes for iron metabolism influence circadian rhythms in Drosophila melanogaster. Metallomics 2012, 4, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sato, M.; Sasahara, M.; Migita, C.T.; Yoshida, T. Unique features of recombinant heme oxygenase of Drosophila melanogaster compared with those of other heme oxygenases studied. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Yoshioka, Y.; Suyari, O.; Kohno, Y.; Zhang, X.; Adachi, Y.; Ikehara, S.; Yoshida, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Taketani, S. Relevant expression of Drosophila heme oxygenase is necessary for the normal development of insect tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavista-Llanos, S.; Centanin, L.; Irisarri, M.; Russo, D.M.; Gleadle, J.M.; Bocca, S.N.; Muzzopappa, M.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Wappner, P. Control of the hypoxic response in Drosophila melanogaster by the basic helix-loop-helix PAS protein similar. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 6842–6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, N.M.; Dekanty, A.; Wappner, P. Cellular and developmental adaptations to hypoxia: A Drosophila perspective. Methods Enzymol. 2007, 435, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.F.; Haddad, G.G. Effects of oxygen on growth and size: Synthesis of molecular, organismal, and evolutionary studies with Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2011, 73, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.B. Behavioral responses to hypoxia and hyperoxia in Drosophila larvae: Molecular and neuronal sensors. Fly 2011, 5, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorr, T.A.; Tomita, T.; Wappner, P.; Bunn, H.F. Regulation of Drosophila hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) activity in SL2 cells: Identification of a hypoxia-induced variant isoform of the HIFalpha homolog gene similar. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 36048–36058. [Google Scholar]

- Centanin, L.; Dekanty, A.; Romero, N.; Irisarri, M.; Gorr, T.A.; Wappner, P. Cell autonomy of HIF effects in Drosophila: Tracheal cells sense hypoxia and induce terminal branch sprouting. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, J.; Masaratana, P.; Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Arno, M.; Simpson, R.J.; McKie, A.T. Duodenal reductase activity and spleen iron stores are reduced and erythropoiesis is abnormal in Dcytb knockout mice exposed to hypoxic conditions. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1929–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.L.; Su, D.; Berczi, A.; Vargas, A.; Asard, H. An ascorbate-reducible cytochrome b561 is localized in macrophage lysosomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1760, 1903–1913. [Google Scholar]

- Sellami, A.; Wegener, C.; Veenstra, J.A. Functional significance of the copper transporter ATP7 in peptidergic neurons and endocrine cells in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 3633–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, S.; Simpson, R.J.; McKie, A.T.; Sharp, P.A. Dcytb (Cybrd1) functions as both a ferric and a cupric reductase in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, T.Z.; Farhad, R.; Lee, K.J.; Santos, A.; Russo, E.; Linder, M.C. Uptake of copper from plasma proteins in cells where expression of CTR1 has been modulated. Biometals 2012, 25, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Padmanabha, D.; Gentile, L.B.; Dumur, C.I.; Beckstead, R.B.; Baker, K.D. HIF- and non-HIF-regulated hypoxic responses require the estrogen-related receptor in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laftah, A.H.; Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Fakih, S.; Hider, R.C.; Simpson, R.J.; McKie, A.T. Haem and folate transport by proton-coupled folate transporter/haem carrier protein 1 (SLC46A1). Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.N.; Bishop, G.M.; Dringen, R.; Robinson, S.R. The putative heme transporter HCP1 is expressed in cultured astrocytes and contributes to the uptake of hemin. Glia 2010, 58, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, S.; Garrick, M.D.; Arredondo, M. Heme carrier protein 1 transports heme and is involved in heme-Fe metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012, 302, C1780–C1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, J.G.; Yang, Z.; Worthington, M.T.; Phillips, J.D.; Sabo, K.M.; Sabath, D.E.; Berg, C.L.; Sassa, S.; Wood, B.L.; Abkowitz, J.L. Identification of a human heme exporter that is essential for erythropoiesis. Cell 2004, 118, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Quigley, J.G. Control of intracellular heme levels: Heme transporters and heme oxygenases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 668–682. [Google Scholar]

- Romney, S.J.; Newman, B.S.; Thacker, C.; Leibold, E.A. HIF-1 regulates iron homeostasis in Caenorhabditis elegans by activation and inhibition of genes involved in iron uptake and storage. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, D.; Gems, D. Insulin/IGF-1 and hypoxia signaling act in concert to regulate iron homeostasis in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitel, G.J.; Krasnow, M.A. Genetic control of epithelial tube size in the Drosophila tracheal system. Development 2000, 127, 3271–3282. [Google Scholar]

- Hentze, M.W.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Andrews, N.C. Balancing acts: Molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 2004, 117, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankeln, T.; Jaenicke, V.; Kiger, L.; Dewilde, S.; Ungerechts, G.; Schmidt, M.; Urban, J.; Marden, M.C.; Moens, L.; Burmester, T. Characterization of Drosophila hemoglobin. Evidence for hemoglobin-mediated respiration in insects. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 29012–29017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmester, T.; Storf, J.; Hasenjager, A.; Klawitter, S.; Hankeln, T. The hemoglobin genes of Drosophila. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleixner, E.; Abriss, D.; Adryan, B.; Kraemer, M.; Gerlach, F.; Schuh, R.; Burmester, T.; Hankeln, T. Oxygen-induced changes in hemoglobin expression in Drosophila. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 5108–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, C.; Korayem, A.M.; Scherfer, C.; Loseva, O.; Dushay, M.S.; Theopold, U. Proteomic analysis of the Drosophila larval hemolymph clot. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 52033–52041. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdusek, O.; Sojka, D.; Kopacek, P.; Buresova, V.; Franta, Z.; Sauman, I.; Winzerling, J.; Grubhoffer, L. Knockdown of proteins involved in iron metabolism limits tick reproduction and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.M.; Kaplan, J. Ferroportin-mediated iron transport: Expression and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Bulet, P.; Hetru, C.; Dimarcq, J.L.; Hoffmann, D. Antimicrobial peptides in insects; structure and function. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1999, 23, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verga Falzacappa, M.V.; Muckenthaler, M.U. Hepcidin: Iron-hormone and anti-microbial peptide. Gene 2005, 364, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charroux, B.; Royet, J. Elimination of plasmatocytes by targeted apoptosis reveals their role in multiple aspects of the Drosophila immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9797–9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denholm, B.; Skaer, H. Bringing together components of the fly renal system. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009, 19, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, J.A. Insights into the Malpighian tubule from functional genomics. J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 212, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.A.; Overend, G.; Sebastian, S.; Cundall, M.; Cabrero, P.; Dow, J.A.; Terhzaz, S. Immune and stress response ‘cross-talk’ in the Drosophila Malpighian tubule. J. Insect Physiol. 2012, 58, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorich, B.; Zhang, X.; Slagle-Webb, B.; Seaman, W.E.; Connor, J.R. Tim-2 is the receptor for H-ferritin on oligodendrocytes. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Paragas, N.; Ned, R.M.; Qiu, A.; Viltard, M.; Leete, T.; Drexler, I.R.; Chen, X.; Sanna-Cherchi, S.; Mohammed, F.; et al. Scara5 is a ferritin receptor mediating non-transferrin iron delivery. Dev. Cell 2009, 16, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorich, B.; Zhang, X.; Connor, J.R. H-ferritin is the major source of iron for oligodendrocytes. Glia 2011, 59, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyron-Holtz, E.G.; Moshe-Belizowski, S.; Cohen, L.A. A possible role for secreted ferritin in tissue iron distribution. J. Neural Transm. 2011, 118, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fang, C.J.; Ryan, J.C.; Niemi, E.C.; Lebron, J.A.; Bjorkman, P.J.; Arase, H.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V.; Nakamura, M.C.; Seaman, W.E. Binding and uptake of H-ferritin are mediated by human transferrin receptor-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 3505–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martin, C.D.; Garri, C.; Pizarro, F.; Walter, T.; Theil, E.C.; Nuñez, M.T. Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells absorb soybean ferritin by mu2 (AP2)-dependent endocytosis. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 659–666. [Google Scholar]

- Bekenstein, U.; Kadener, S. What can Drosophila teach us about iron-accumulation neurodegenerative disorders? J. Neural Transm. 2011, 118, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamilos, G.; Lewis, R.E.; Hu, J.; Xiao, L.; Zal, T.; Gilliet, M.; Halder, G.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Drosophila melanogaster as a model host to dissect the immunopathogenesis of zygomycosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9367–9372. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, N.; Voronin, D.; Charif, D.; Mavingui, P.; Mollereau, B.; Vavre, F. Wolbachia interferes with ferritin expression and iron metabolism in insects. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlie, J.C.; Cass, B.N.; Riegler, M.; Witsenburg, J.J.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; McGraw, E.A.; O’Neill, S.L. Evidence for metabolic provisioning by a common invertebrate endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, during periods of nutritional stress. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.P.; Hanna, S.L.; Spiridigliozzi, A.; Wannissorn, N.; Beiting, D.P.; Ross, S.R.; Hardy, R.W.; Bambina, S.A.; Heise, M.T.; Cherry, S. Natural resistance-associated macrophage protein is a cellular receptor for sindbis virus in both insect and mammalian hosts. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.S.; Codrea, M.C.; Vermeulen, C.J.; Loeschcke, V.; Bendixen, E. Proteomic characterization of a temperature-sensitive conditional lethal in Drosophila melanogaster. Heredity 2010, 104, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.A.; Kellie, J.F.; Kaufman, T.C.; Clemmer, D.E. Insights into aging through measurements of the Drosophila proteome as a function of temperature. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2010, 131, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colinet, H.; Overgaard, J.; Com, E.; Sorensen, J.G. Proteomic profiling of thermal acclimation in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 43, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizares, J.; Blanca, J.M.; Navarro, J.A.; Monros, E.; Palau, F.; Molto, M.D. dfh is a Drosophila homolog of the Friedreich’s ataxia disease gene. Gene 2000, 256, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.R.; Kirby, K.; Hilliker, A.J.; Phillips, J.P. RNAi-mediated suppression of the mitochondrial iron chaperone, frataxin, in Drosophila. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 3397–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, J.V.; Navarro, J.A.; Martinez-Sebastian, M.J.; Baylies, M.K.; Schneuwly, S.; Botella, J.A.; Molto, M.D. Causative role of oxidative stress in a Drosophila model of Friedreich ataxia. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.R.; Kirby, K.; Orr, W.C.; Hilliker, A.J.; Phillips, J.P. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging rescues frataxin deficiency in a Drosophila model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runko, A.P.; Griswold, A.J.; Min, K.T. Overexpression of frataxin in the mitochondria increases resistance to oxidative stress and extends lifespan in Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidara, Y.; Hollenbeck, P.J. Defects in mitochondrial axonal transport and membrane potential without increased reactive oxygen species production in a Drosophila model of Friedreich ataxia. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 11369–11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.A.; Llorens, J.V.; Soriano, S.; Botella, J.A.; Schneuwly, S.; Martinez-Sebastian, M.J.; Molto, M.D. Overexpression of human and fly frataxins in Drosophila provokes deleterious effects at biochemical, physiological and developmental levels. PLoS One 2011, 6, e21017. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, S.; Llorens, J.V.; Blanco-Sobero, L.; Gutiérrez, L.; Calap-Quintana, P.; Morales, M.P.; Moltó, M.D.; Martínez-Sebastián, M.J. Deferiprone and idebenone rescue frataxin depletion phenotypes in a Drosophila model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Gene 2013, 521, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Ramirez, L.; Jimenez-Del-Rio, M.; Velez-Pardo, C. Low doses of paraquat and polyphenols prolong life span and locomotor activity in knock-down parkin Drosophila melanogaster exposed to oxidative stress stimuli: Implication in autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism. Gene 2013, 521, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G.; Vos, M.; Vilain, S.; Swerts, J.; de Sousa Valadas, J.; van Meensel; Schaap, O.; Verstreken, P. Aconitase causes iron toxicity in Drosophila pink1 mutants. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003478. [Google Scholar]

- Rival, T.; Page, R.M.; Chandraratna, D.S.; Sendall, T.J.; Ryder, E.; Liu, B.; Lewis, H.; Rosahl, T.; Hider, R.; Camargo, L.M.; et al. Fenton chemistry and oxidative stress mediate the toxicity of the beta-amyloid peptide in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Moloney, A.; Meehan, S.; Morris, K.; Thomas, S.E.; Serpell, L.C.; Hider, R.; Marciniak, S.J.; Lomas, D.A.; Crowther, D.C. Iron promotes the toxicity of amyloid beta peptide by impeding its ordered aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 4248–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Pranski, E.; Miller, R.D.; Radmard, S.; Bernhard, D.; Jinnah, H.A.; Betarbet, R.; Rye, D.B.; Sanyal, S. Sleep fragmentation and motor restlessness in a Drosophila model of Restless Legs Syndrome. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.A.; Mandilaras, K.; Missirlis, F.; Sanyal, S. An emerging role for Cullin-3 mediated ubiquitination in sleep and circadian rhythm: Insights from Drosophila. Fly 2013, 7, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, S.; Botella, J.A.; Mandilaras, K.; Schneuwly, S.; Skoulakis, E.M.; Rouault, T.A.; Missirlis, F. Ferritin overexpression in Drosophila glia leads to iron deposition in the optic lobes and late-onset behavioral defects. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 43, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Ramirez, L.; Jimenez-Del-Rio, M.; Velez-Pardo, C. Acute and chronic metal exposure impairs locomotion activity in Drosophila melanogaster: A model to study Parkinsonism. Biometals 2011, 24, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Du, Y.; Xue, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, B. Aluminum induces neurodegeneration and its toxicity arises from increased iron accumulation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 199.e1–199.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, O.V.; Lushchak, O.V.; Storey, J.M.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Sodium nitroprusside toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster: Delayed pupation, reduced adult emergence, and induced oxidative/nitrosative stress in eclosed flies. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 80, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, K.S.; Meyer, F.; Vazquez, A.V.; Flotenmeyer, M.; Cerdan, M.E.; Moussian, B. Delta-aminolevulinate synthase is required for apical transcellular barrier formation in the skin of the Drosophila larva. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 91, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzendorf, C.; Lind, M.I. Drosophila mitoferrin is essential for male fertility: Evidence for a role of mitochondrial iron metabolism during spermatogenesis. BMC Dev. Biol. 2010, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzendorf, C.; Wu, W.; Lind, M.I. Overexpression of Drosophila mitoferrin in l(2)mbn cells results in dysregulation of Fer1HCH expression. Biochem. J. 2009, 421, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, K.G. Iron testes: Sperm mitochondria as a context for dissecting iron metabolism. BMC Biol. 2010, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Deshpande, A.; Missirlis, F. Genetic screening for novel Drosophila mutants with discrepancies in iron metabolism. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008, 36, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzendorf, C.; Lind, M.I. The role of iron in the proliferation of Drosophila l(2) mbn cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 400, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Identification of iron-loaded ferritin as an essential mitogen for cell proliferation and postembryonic development in Drosophila. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, J.C.; Hwang, J.E.; Paterson, D.; de Jonge, M.D.; Howard, D.L.; Burke, R. Detection of genetically altered copper levels in Drosophila tissues by synchrotron X-ray fluorescence microscopy. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26867. [Google Scholar]

- Drakesmith, H.; Prentice, A.M. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis. Science 2012, 338, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, B.; Hoffmann, J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 697–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Lewis, R.E. Invasive zygomycosis: Update on pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2006, 20, 581–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, R.J.; Benzer, S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 2112–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitabach, M.N.; Taghert, P.H. Organization of the Drosophila circadian control circuit. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, R84–R93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioum, E.M.; Rutter, J.; Tuckerman, J.R.; Gonzalez, G.; Gilles-Gonzalez, M.A.; McKnight, S.L. NPAS2: A gas-responsive transcription factor. Science 2002, 298, 2385–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasik, K.; Lee, C.C. Reciprocal regulation of haem biosynthesis and the circadian clock in mammals. Nature 2004, 430, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinking, J.; Lam, M.M.; Pardee, K.; Sampson, H.M.; Liu, S.; Yang, P.; Williams, S.; White, W.; Lajoie, G.; Edwards, A.; Krause, H.M. The Drosophila nuclear receptor e75 contains heme and is gas responsive. Cell 2005, 122, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosny, E.; de Groot, A.; Jullian-Binard, C.; Borel, F.; Suarez, C.; le Pape, L.; Fontecilla-Camps, J.C.; Jouve, H.M. DHR51, the Drosophila melanogaster homologue of the human photoreceptor cell-specific nuclear receptor, is a thiolate heme-binding protein. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 13252–13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salome, P.A.; Oliva, M.; Weigel, D.; Kramer, U. Circadian clock adjustment to plant iron status depends on chloroplast and phytochrome function. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 511–523. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Kim, S.A.; Guerinot, M.L.; McClung, C.R. Reciprocal interaction of the circadian clock with the iron homeostasis network in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Shin, L.J.; Wu, J.F.; Shanmugam, V.; Tsednee, M.; Lo, J.C.; Chen, C.C.; Wu, S.H.; Yeh, K.C. Iron is involved in the maintenance of circadian period length in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.T.; Connolly, E.L. Running a little late: Chloroplast Fe status and the circadian clock. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shahar, Y.; Dudek, N.L.; Robinson, G.E. Phenotypic deconstruction reveals involvement of manganese transporter malvolio in honey bee division of labor. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 207, 3281–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, R.; Raymond-Delpech, V. Insights into the molecular basis of social behaviour from studies on the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Invert. Neurosci. 2008, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, V.; Montermini, L.; Molto, M.D.; Pianese, L.; Cossee, M.; Cavalcanti, F.; Monros, E.; Rodius, F.; Duclos, F.; Monticelli, A.; et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: Autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 1996, 271, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, M.; de Silva, D.; Oaks, R.; Davis-Kaplan, S.; Jiralerspong, S.; Montermini, L.; Pandolfo, M.; Kaplan, J. Regulation of mitochondrial iron accumulation by Yfh1p, a putative homolog of frataxin. Science 1997, 276, 170–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Rötig, A.; de Lonlay, P.; Chretien, D.; Foury, F.; Koenig, M.; Sidi, D.; Munnich, A.; Rustin, P. Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 215–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadorani, S.; Hilliker, A.J. Cocoa confers life span extension in Drosophila melanogaster. Nutr. Res. 2008, 28, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Del-Rio, M.; Guzman-Martinez, C.; Velez-Pardo, C. The effects of polyphenols on survival and locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster exposed to iron and paraquat. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriner, S.E.; Katoozi, N.S.; Pham, K.Q.; Gazarian, M.; Zarban, A.; Jafari, M. Extension of Drosophila lifespan by Rosa damascena associated with an increased sensitivity to heat. Biogerontology 2012, 13, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadraie, M.; Missirlis, F. Evidence for evolutionary constraints in Drosophila metal biology. Biometals 2011, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandilaras, K.; Pathmanathan, T.; Missirlis, F. Iron Absorption in Drosophila melanogaster. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1622-1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051622

Mandilaras K, Pathmanathan T, Missirlis F. Iron Absorption in Drosophila melanogaster. Nutrients. 2013; 5(5):1622-1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051622

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandilaras, Konstantinos, Tharse Pathmanathan, and Fanis Missirlis. 2013. "Iron Absorption in Drosophila melanogaster" Nutrients 5, no. 5: 1622-1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051622