Abstract

Ensuring sustainable consumption and production is one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable consumption can be supported through regulatory processes. Voluntary private regulatory schemes claiming to contribute to sustainability are a rapidly growing form of regulation. We study one such voluntary sustainability scheme in order to look at the opportunities and challenges this type of regulatory process poses using Abbot and Snidal’s regulatory standard-setting framework (2009). Specifically, we examine direct trade voluntary schemes in the coffee industry. To do this, we selected six leading direct trade firms in the US and Scandinavia, analyzed firms’ websites in 2015 and 2016 and conducted interviews with four of the firms. We found direct trade as a voluntary scheme was an attempt to market and codify good sourcing practices. US-based founding firms have distanced themselves from the term due to perceived co-optation, which we conceptualize as the failure of industry to self-regulate and argue was enabled by the re-negotiation of standards without the power to enforce or penalize misuse of the term. Firms reacted to co-optation by releasing data to consumers directly; we argue this puts too much responsibility on consumers to monitor and enforce standards. By contrast, Scandinavian firms maintained standards enforced through trademark nationally. Both US and Scandinavian contexts demonstrate a weakness of firm-led agenda-setting for sustainable development in that schemes may be optimized for a particular business concern—in this case quality—rather than to achieve sustainable development goals. This is problematic if schemes are marketed on contribution to the public good when incentives within the scheme are not aligned to produce an optimal result for the public good.

1. Introduction

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 is to “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” [1]. Consumption drives resource use and the world is using resources at an unsustainable rate. Reducing the rate of resource use would require decreasing consumption and improving production. In the context of food systems, consumption is expected to rise due to increasing populations, affluence and dietary change [2], yet simultaneously food system production must reduce its environmental impact from land use change as well as water, energy and fertilizer usage [3]; food systems are responsible for 19%–29% of global anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions [4]. Concurrently, there is a need to improve the livelihoods of people working in food system value chains. Regulation is one way of improving such production patterns.

There are competing models for how to regulate on a transnational scale to support sustainable consumption and production. Particularly popular now are roundtables and certification, as seen in palm oil [5] and the Forest Stewardship Council [6] respectively. These follow a trend in regulation in which voluntary standards and non-state involvement in regulatory processes are increasing [7,8]. There is not agreement on the best model for regulating towards more sustainable production [9,10,11] and this seems to differ based on condition and context [12,13,14,15], something that we explore in this paper.

The coffee industry has arguably the most advanced experience from a regulatory perspective with sustainable labeling [16], another increasingly popular form of regulation. Coffee has a long history with sustainable consumption movements [17], in which consumers choose labeled coffee that claims to support better production practices, for example Fair Trade, Organic, UTZ Certified, Rainforest Alliance or Bird Friendly. This effort is recognized for example in the UN’s summary of “Responsible Consumption and Production: Why it matters” [18] where there is a single image: a handful of coffee cherries.

Yet coffee consumption and production remain problematic. Although demand for coffee is increasing, livelihoods of coffee producers remain uncertain [19]. Coffee also embodies production problems facing agricultural products generally; climate change is negatively impacting coffee production [20,21] and coffee trading has been shown to threaten biodiversity [22].

This paper analyzes the development of voluntary regulatory schemes claiming to support sustainable production and consumption by looking within the mature labeling landscape of the specialty coffee industry at voluntary schemes called “direct trade” in the United States of America (US) and Scandinavia (specifically Sweden and Denmark). The use of direct trade as a standalone term, rather than as a Fair Trade principle, was popularized by the Chicago-based firm Intelligentsia [23] beginning around 2005 and Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification was established in 2008; the use of the term direct trade has since spread rapidly [24]. Generally the stated purpose of direct trade is to facilitate regularly procuring high quality coffee in a sustainable way.

Discussions about direct trade can become muddled as the term is used in three different ways in the coffee industry: first, as a general concept for coffee sourcing; second, as a marketing strategy; and third, as a voluntary scheme. In this article, we will focus specifically on direct trade as a voluntary scheme. Direct trade as a concept for coffee sourcing refers to having direct and regular contact between roasting firms and coffee producers, which is typically represented by practices such as coffee buyers from roasting firms visiting coffee producers, with quality-based prices paid directly to producers. Direct trade as a marketing strategy refers to the use of the term direct trade to sell coffee to consumers. A voluntary scheme is a claim that a particular set of standards is followed. In the case of direct trade voluntary schemes, firms claim, usually via a logo targeted at consumers (marketing strategy), to follow a particular set of standards (coffee sourcing practices). Thus, direct trade voluntary schemes refer to making coffee sourcing practices marketable in the form of a voluntary regulatory program by guaranteeing a particular set of standards are followed. Direct trade is a voluntary scheme because firms choose whether to be involved; it is not a mandatory regulation requiring participation.

Direct trade voluntary schemes can be classified as sustainability schemes because they contain claimed sustainability standards. Specifically, direct trade voluntary schemes claim to contribute to sustainability through coffee sourcing practice standards that ensure traceability in an identity preserved model [25] and through financial incentives for high quality coffee.

This study compares the regulatory standard-setting process behind direct trade voluntary schemes in two different contexts—the US and Scandinavia—and analyzes changes in the content and use of the schemes between 2015 and 2016. We study these direct trade voluntary schemes in order to understand the opportunities and challenges that different regulatory approaches involving firms, such as firm self-regulatory schemes or collaborative governance between non-governmental organizations and firms, pose for the development of voluntary sustainability schemes. To compare the development of direct trade as a voluntary scheme in the US and Scandinavia, we selected three US firms credited with founding, developing and popularizing direct trade and three Scandinavian firms–two representing the owners of trademarked direct trade voluntary schemes and one of a non-trademarked direct trade scheme. These schemes share agenda, name and basic standards, yet differ in terms of actors involved in regulatory governance and competencies in the regulatory standard-setting process. We look at direct trade in the US and Scandinavia because direct trade schemes have developed differently with noticeably different outcomes in terms of use of direct trade: in the US, founding direct trade firms have been backing away from the term direct trade and have complained that others have co-opted the term. Meanwhile, in Scandinavia, trademarked direct trade voluntary schemes have remained stable, while non-trademarked direct trade schemes have been abandoned. We analyze the present-day development of direct trade because there were dramatic shifts in the usage of the term direct trade between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, a founding direct trade firm, Counter Culture, abandoned its third-party Direct Trade Certification program. This marked the end of ambitions to develop a formal direct trade certification program. Yet direct trade as a voluntary scheme remains and the term direct trade itself continues to increase in popularity.

The aim of this paper is to examine the development of direct trade coffee voluntary schemes in the US and Scandinavia as examples of regulatory standard-setting processes. We do this in order to see whether such schemes offer a way forward for more radical transformation of agricultural value chains to support sustainable production and consumption by exploring the opportunities and constraints arising for voluntary schemes whose development involved firms. Our overarching research question is: What are the implications for sustainable production and consumption of regulatory approaches involving firms? We address this question through two sub-questions: (1) How have direct trade schemes developed at each stage (agenda-setting, negotiation of standards, implementation, monitoring, enforcement) of the regulatory-standard setting process over the past few years in the US and Scandinavia? (2) What approaches within regulatory space do these processes represent within the US and Scandinavian contexts? In the discussion section we consider differences in regulatory processes and outcomes in order to examine the opportunities and limitations of firms as actors within regulatory governance.

2. Theory

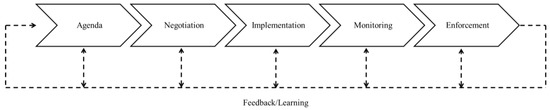

Regulatory standard-setting is the process of developing either voluntary or mandatory standards, which ultimately seek to improve production and consumption patterns. The regulatory standard-setting process consists of five stages: agenda-setting, negotiation, implementation, monitoring and enforcement (Figure 1) [26]. Agenda-setting concerns what issues are placed on the regulatory agenda and how those issues are framed. Negotiation of standards is the process of defining exactly what standards entail. Implementation involves putting the standards into practice. Monitoring refers to tracking how well the standards are followed both internally and externally, for instance via in-house evaluation or verification by a third party. Enforcement concerns the use of rewards and penalties related to adherence to the standards.

Figure 1.

Conceptual figure showing the five stages of the regulatory process. Adapted from Abbott and Snidal [26] (p. 63) with permission from Princeton University Press.

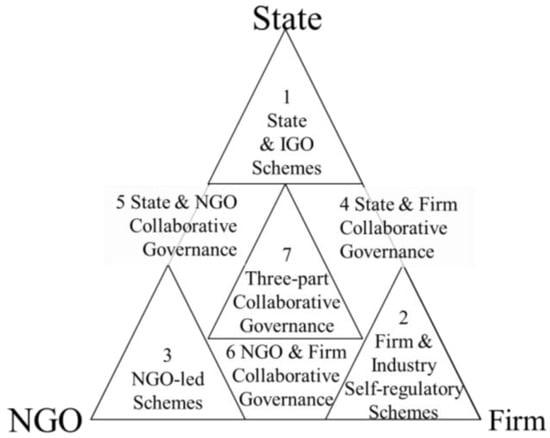

The regulatory triangle (Figure 2) visualizes direct involvement of three key actors within transnational regulatory space: state, non-governmental and firm actors [26]. Actor involvement is mapped within the regulatory triangle based on the level and importance of direct involvement, including decision-making power, through the regulatory standard-setting stages. For example, national laws would be considered state schemes (zone 1) because decision-making power lies in the hands of state actors through legislative enactment. Firms may be involved in the process, for instance through lobbying, but this is considered indirect influence because the final action of enacting legislation is entirely in the hands of state actors [26].

Figure 2.

Abbott and Snidal’s regulatory triangle [26] visualizes the involvement of state, non-governmental organizations (NGO), and firm actors in regulatory standard-setting within regulatory space. The closer a regulatory scheme is to any corner of the triangle (zones 1–3) the more one type of actor dominated the regulatory standard-setting process. The spaces between triangles (zones 4–6) represent co-regulation between two actor types and the triangle in the middle (zone 7) represents a collaborative scheme involving all three types of actors. Examples of schemes involving firm actors include: zone 2 Sustainable Forestry Initiative, zone 4 UN Global Compact Caring for Climate, zone 6 Fairtrade Labeling Organization, and zone 7 Roundtable on Sustainable Biofuels [26,27]. IGO stands for intergovernmental organization. Adapted from Abbott & Snidal [26] (p. 50) with permission from Princeton University Press.

This mapping gives an overall impression of the structure of the scheme and is intended to make schemes comparable, even if they appear different on the surface [27]. Mapping schemes within the triangle prioritizes positioning schemes relative to other schemes over precise positioning of these complex schemes within the triangle [26]. This structural comparison helps in analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of various approaches, as different actors tend to have different levels of capacity in necessary competencies for regulation, such as expertise, operational capacity, independence and representativeness [26].

We use the regulatory standard-setting framework to compare the development of direct trade voluntary schemes in the US and Scandinavia. We analyze coalitions of actors involved in developing the schemes in order to explore differing outcomes in direct trade usage between the US and Scandinavia related to actor competencies.

3. Methods

In our study of direct trade voluntary schemes, we analyzed six firms’ public communications related to direct trade by studying their websites from 2015 and 2016 as well as conducting interviews with representatives from four of the firms in 2016. This analysis focused on the stages of the regulatory standard-setting process, looked for changes from 2015 to 2016, and investigated motivations behind these changes.

3.1. Case Selection

We selected six direct trade roasting firms, three US (Counter Culture Coffee, Intelligentsia Coffee and Stumptown Coffee Roasters) and three Scandinavian (The Coffee Collective, Johan & Nyström and Koppi) because these firms are the creators or owners of direct trade (Table 1). We studied influential firms because direct trade is informally structured with no single spokesperson or unified organization. The three US firms were selected because they are widely credited as being foundational in developing and popularizing direct trade, they were identified by the Scandinavian firms as leaders in an international context and they explicitly define their coffee as direct trade [28,29,30]. In Denmark and Sweden the term direct trade itself is trademarked by individual firms (Table 1) so we chose to study trademark-owning firms in these countries—The Coffee Collective and Johan & Nyström, respectively. We selected one additional Swedish firm, Koppi, because when the study began in 2015 they used the term direct trade differently than the Swedish trademark owner, although they have since stopped using the term.

Table 1.

Profiles of the six direct trade firms analyzed in this study. Location refers to the number of cafes, roasteries and training centers of each firm. This number is intended to give an impression of the size of these firms, although their products are sold in many more locations through wholesale and by other retailers. Information was taken from company websites in spring 2015 and fall 2016 [31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

3.2. Text Analysis

We examined the development of direct trade voluntary schemes in the US and Scandinavia by conducting text analysis of the six firms’ websites [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] between January and April 2015 and then again between June and September 2016. Hundreds of webpages were studied and 194 webpages were categorized as relevant based on explicit reference to direct trade or related standards, which were then collected, saved and analyzed using NVIVO [40]. In 2015, we collected webpages, including blog posts, and documents on webpages explicitly referencing direct trade or direct trade standards as well as firm history and mission statements (107 webpages). In 2016 we collected the equivalent updated webpages and documents (87 webpages). We compared the standards, definitions, descriptions, prominence and placement of direct trade between the 2015 and 2016 webpages to highlight changes and the justification provided by firms for these changes.

3.3. Interviews

In order to corroborate the findings of the initial text analysis and to explore more deeply how and why direct trade as a voluntary scheme has changed, we conducted semi-structured interviews with individuals from the firms. We invited all six firms via repeated targeted emails, phone calls and website-based inquiry where available. Employees from four of the six firms agreed to be interviewed in spring 2016. All interviewees gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. In order to protect individual privacy, we refer to interviewees based on the company they represent (Table 2). Interviewees selected have extensive and daily experience with direct trade at their firm. Themes covered in these interviews included how interviewees define direct trade, why they use direct trade, how standards were initially developed, how standards are adapted, changes in direct trade usage in the last year within their own firm and in general usage and why they think direct trade has changed. Responses were analyzed to identify changes in direct trade regulatory practice at their company, interviewee perception of direct trade changes more generally and motivations for change.

Table 2.

Four 45-minute semi-structured interviews were conducted via Skype or in person with individuals from four direct trade coffee firms. Interviewees will be referenced within this paper using the interviewee codes listed below.

4. Results

This section begins with a systematic overview, based on data drawn from website analysis and interviews, of each firm’s direct trade scheme content (Table 3), development (Table 4), and usage and prominence (Table 5) between 2015 and 2016. The sub-sections then describe in greater depth the development of direct trade in the contexts of the US and Scandinavia through the regulatory standard-setting stages.

Table 3.

Shows the content of direct trade voluntary schemes in 2015 and 2016 across firms by identifying content of standards within schemes and claimed indirect benefits of those standards. Symbols represent presence of a standard or claimed benefit in a particular topic; symbols do not assess quality or stringency of standards. Based on firm webpages defining direct trade schemes in 2015 and 2016 [36,41,42,43,44,45,46].

Table 4.

Summarizes the actors involved in each stage of the regulatory standard-setting process for each firm. Actors in parentheses play a passive or less powerful role in the stage. Information was taken from interviews and company websites in spring 2015 and fall 2016 [31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Table 5.

This table summarizes the prominence and use of direct trade by firms. Direct trade web presence was determined based on links to direct trade from homepage, direct trade filter for purchasing, dedicated direct trade definition, identification of individual products as direct trade and use of direct trade logo. The use of direct trade columns summarize firm direct trade practice for a given year: voluntary scheme refers to actual regulatory programs guaranteeing specified criteria as opposed to use as a concept without specified criteria, and not used means firms no longer use the term to describe products. Information was taken from company websites in spring 2015 and fall 2016 [31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

The content of standards within direct trade voluntary schemes differs somewhat by firm (Table 3). The most widely shared topics of direct trade standards relate to coffee quality, price premiums and regular visits of the roasting firm to the producer, and in 2015 all schemes had at least one quantifiable standard. Coffee quality in this context relates to cupping scores, meaning the taste of the coffee, and price is based on incentivizing coffee quality, sometimes with a guaranteed minimum price. All firms using direct trade logos also have a standard related to financial transparency. We defined financial transparency as, at minimum, the roaster knowing whom the producer is and paying them directly, but more stringent standards require additional disclosures to producers or consumers. Sustainable social practices, environmental requirements and long-term commitment have standards only for some schemes. External auditing is rare; it was only used by Counter Culture as part of their certification program.

The actors involved in the stages of regulatory standard-setting for these direct trade voluntary schemes heavily—but not exclusively—involved firms (Table 4). Regulatory agendas of direct trade schemes were set by and schemes were implemented by individual firms internally across the board. Monitoring was primarily done by firms internally, meaning that individual firms verify and self-report compliance. Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification was the exception in that the NGO Quality Certification Services monitored and verified the firm Counter Culture’s compliance. In the US, interviewees (CCC, ST) emphasized the pressure coming from other firms in the industry in the continued development of direct trade schemes, as seen in the negotiation of standards column (Table 4). Similarly, all interviewees acknowledged the lack of formal enforcement capable of preventing or penalizing misuse of direct trade schemes in the US; additionally US interviewees (CCC, ST) stated reluctance to call out scheme misuse by other firms. Without formal penalties or shaming tactics, US firms attempted enforcement through soft power of influence and convincing others. By contrast, two Scandinavian firms involved state actors in negotiation and enforcement stages through trademarking direct trade schemes within their own countries.

The period from 2015 to 2016 represented rapid change in general usage of and prominence of direct trade schemes. All firms must have made active decisions about how to present direct trade voluntary schemes online because five of the six firms restructured and redesigned their websites during this time period and the sixth firm, The Coffee Collective, revised and restructured the specific webpage on which their scheme is defined. Two firms no longer use direct trade voluntary schemes; Counter Culture terminated its Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification scheme and Koppi rebranded their scheme (Table 5). Through restructuring their websites, both Stumptown and Intelligentsia decreased the visibility of their direct trade schemes (Table 5). In updating direct trade specific webpages Intelligentsia revised the wording of their direct trade scheme while maintaining the content of the standards (Table 3) and their commitment to the scheme [47]. The Stumptown interviewee indicated there were not changes to Stumptown’s direct trade scheme. However, the restructured Stumptown website in 2016 no longer has a dedicated direct trade webpage and the new text describing direct trade is shorter, less detailed and states fewer standards (Table 3), so communication of the scheme has changed. The two Scandinavian firms with trademarked voluntary schemes maintained the use, content and prominence of their schemes during this time.

4.1. Development of Direct Trade in the US

Here we examine the development of direct trade as a regulatory standard-setting process in the context of the US by focusing on three founding firms introduced below. We do this by examining agenda-setting, negotiation of standards, implementation, monitoring and enforcement stages individually and then mapping their regulatory approach within the governance triangle.

Intelligentsia is a quality-driven, rapidly growing firm that claims to have “pioneer[ed] the concept of direct trade” [47]. One notable element of their direct trade scheme is their annual Extraordinary Coffee Workshop [48], which brings together actors from across the supply chain to a producer region for five days.

Counter Culture Coffee is known for their sustainable business mission. They were already identified by the New York Times as a direct trade roaster in 2007 [23], but it officially launched the first third-party authenticated direct trade certification scheme in May 2008 [49]. They presented their direct trade scheme as a “quality-driving approach to sustainability” supporting “sustainability-focused business practices” and “informed purchasing decisions” [49]. The widespread use of the term direct trade, without similar standards, led Counter Culture to abandon its direct trade certification scheme in 2015, replacing it with “Purchasing Principles” [50] (CCC).

Stumptown Coffee Roasters is a rapidly expanding firm characterized by its pursuit of highest quality coffee. The Stumptown interviewee explained the use of their direct trade scheme based on business, saying direct trade is what allows Stumptown to regularly obtain large quantities of high-quality coffee, but they also claim sustainability benefits result from it. Stumptown’s direct trade scheme emphasizes context, arguing for contextually applied practices and against universal standards regardless of context (ST).

4.1.1. Agenda-Setting in the US

Agenda-setting in the US context reflects the concerns of roasting firms, namely desires for quality and claims backed by data. The regulatory agenda for the development of direct trade is grounded in business practices of roasting companies working with high-quality coffee. The Stumptown interviewee described direct trade as not “simply a marketing tool… not because we want to feel good; it’s … the best way to get the best coffee” (ST). As this regulatory agenda represents the perspective of roasting firms, there is an emphasis on making good sourcing practices marketable or “how do we best use everything we’re doing to be able to sell the coffee as well” (ST). As Counter Culture put it “We originally created DT [direct trade] certification as a way to capture how we buy coffee” [50].

This desire for high-quality coffee justifies the need for direct trade in the eyes of founding companies and they criticize the limitations of commodity and certified coffees. Coffee sold as a commodity is criticized for its lack of quality and lack of “transparency along the supply chain” with the direct trade scheme being presented as an “alternative method of exchange to source, procure and develop relationships in coffee” (ST). Certified coffees, Fair Trade in particular, were criticized for their lack of quality incentives: “[With Fair Trade] we realized the prices that we’re paying are not tied to quality at all, so it’s really hard to improve quality because there aren’t any incentives to do so. And that’s why we kind of moved to… make our own Direct Trade Certification.” (CCC).

This suggests that the founders of direct trade schemes prefer high-quality coffee over ethically produced certified coffee of lesser quality, which demonstrates that sustainability is not the primary driver of direct trade. “You know we can only accept a very high quality of coffee so even if something is certified as being ethically sourced or ethically produced it doesn’t always work. So that quality component becomes crucial…” (ST). However, firms do make sustainability claims as they consider sustainability to be an outcome of the direct trade scheme. The same Stumptown interviewee quoted above connects these issues of quality and sustainability directly, arguing that direct trade “contributes incredibly to sustainable practices in the long term” because in order to obtain “year after year consistent quality” the producer must have a “well managed forest” that “very carefully” maintains “shade canopy… biodiversity… clean water source.” Similarly, individual direct trade standards are presented as sustainable, as in “sustainable prices” [42] and “sustainable social practices” [43].

While direct trade is a rejection of existing certification schemes, it is still focused on the idea of credible claims. Many high-quality coffee firms tell stories of farmers and claim to pay good prices, but founding firms critiqued their inability to back up those claims with data: “We could write a lot about how we buy coffee, but it doesn’t mean much without the data to back it up” [50]. Direct trade schemes strongly value “transparency along the supply chain” (ST).

4.1.2. Negotiation of Standards in the US

Each firm internally defines its own direct trade scheme’s standards. Initially the negotiation of standards across the market was dominated by the founding firms who had quite similar standards. However, weaker direct trade schemes are increasingly common, as more firms have developed their own direct trade schemes with weaker standards. In all cases, the initial development of and amending of each scheme’s standards were presented as a process involving only roaster firms without involvement from state or non-governmental actors. When specifically asked about the roles of these actors in the development of standards, interviewees’ responses could be summarized as “Not so much…” (ST).

Direct trade schemes’ standards are negotiated within individual firms, with the three founding firms using similar standards. For founding firms, developing direct trade standards was about “captur[ing] our coffee-buying philosophy” [50] and was a formalization of existing good coffee sourcing practices. The standards themselves were developed among small groups of individuals that have worked together for years within a single firm, such as the coffee team or founders. These small groups still control implementation and changes to direct trade standards within each firm.

“So we have a coffee team here—it’s coffee sourcing, our head roaster, our director of coffee, our head of quality control—and we’re all working on these things day in and day out... We simply get together and adapt. We have our basic parameters of what direct trade is… we’ve had a few sincere re-evaluations and come to the conclusion that we’re going to keep doing it the way we’ve been doing it…”(ST)

Founding firms initially disagreed on whether direct trade should aim to become a more formal certification program, but now the three founders use a firm self-regulatory approach and they describe each other’s standards as “the most similar” (ST).

As many firms began using their own direct trade schemes, the discourse of what direct trade standards entail shifted to weaker definitions in the US, according to interviewees (ST, CCC, TCC). Interviewees noted a general increase in the use of the term direct trade by other firms and presented this in a negative light. The Stumptown interviewee described the “popping up” of “hundreds” of roasters in Portland that “claim to be direct trade roasters” but was dismissive of their version of direct trade in which “they might have gone on an origin visit, they might have taken a picture and met the farmer” but do it simply as a “marketing tool.” Counter Culture described the same phenomenon in which “lots of other coffee companies are using the term ‘direct trade’… [leading] to the term becoming somewhat diluted and nebulous and hence confusing [as] consumers are getting a lot of different messages” [50].

4.1.3. Implementation in the US

Despite the growing popularity of the term direct trade within the US, founding firms have been quietly backing away from direct trade voluntary schemes over time. This is most noticeable with Counter Culture Coffee, who ended their Direct Trade Certification program in 2015. This trend can also be seen through web presence of direct trade schemes across firms (Table 5) and small actions that de-emphasize the term direct trade.

Counter Culture Coffee replaced their Direct Trade Certification program with Purchasing Principles. By comparing the main tenents of their direct trade certification scheme, using their old certification scheme standards, to the current Purchasing Principles, we identified differences between them (Table 6). Counter Culture claims the move from direct trade certification to Purchasing Principles “is not a change in our coffee-buying practices, rather it’s an evolution in the way we communicate those practices” [50]. We found the changes constitute a regulatory shift away from an NGO and firm collaborative governance through third-party certification (Table 6). Counter Culture claims to maintain the good sourcing practices of direct trade and to have expanded the scope of such practices to all coffee products, though the Purchasing Principles are guidelines rather than guaranteed standards with quantified minimum requirements. Rather than third-party verification, the firm releases data directly to consumers, in the form of annual transparency and sustainability reports [51]. Counter Culture argues this represents increased transparency as more data, covering additional aspects of production and more products, are being released to consumers.

Table 6.

Counter Culture’s change from direct trade certification standards in the beginning of 2015 to Purchasing Principles in mid-2016, based on analysis of website and company materials.

Counter Culture explained their reasoning for discontinuing their direct trade certification scheme and developing Purchasing Principles as due to general problems with certification, confusion around the term direct trade due to competing firms’ standards and a move to broaden the scope of sourcing practices and reporting [50,52]. Their first argument is that certification “creates a false separation in our coffees” [50] meaning that it divides products between certified presumed good products and non-certified presumed bad products, which limits visibility of “continuous improvement” (CCC). Confusion around the term direct trade is a problem that comes from negotiation and enforcement stages, yet led to changes in implementation. “[Direct trade] can be greenwashing for sure and that’s why we’re trying to—I don’t want to say step away from the term direct trade because that still describes what we’re trying to do, but not to try to codify it, and own it anymore…” (CCC).

Counter Culture no longer puts a direct trade logo on their packaging (Table 3), but the interviewee stated when prompted that all their coffees could be considered direct trade because they follow purchasing principles. Purchasing Principles is the term Counter Culture now uses to market their sourcing practices.

Stumptown has quietly backed away from describing itself as direct trade. According to the interviewee, Stumptown maintained direct trade practices, but changes to their website de-emphasize the term. Stumptown no longer has a webpage dedicated to explaining direct trade as they had in 2015 [41]; instead there is only a short description of direct trade buried within the sourcing sub-section of their webpage about the company [45]. In 2015, direct trade was presented as representing specific pillars related to sourcing practices, whereas now it is presented more broadly as “We shoot for sustainability, and not just in the environmental sense” [45]. When purchasing coffee online, consumers are no longer able to filter results for direct trade coffees [53] as they were previously [54]. Individual products are still described as direct trade, but Stumptown’s direct trade logo is no longer on product webpages [55].

4.1.4. Monitoring in the US

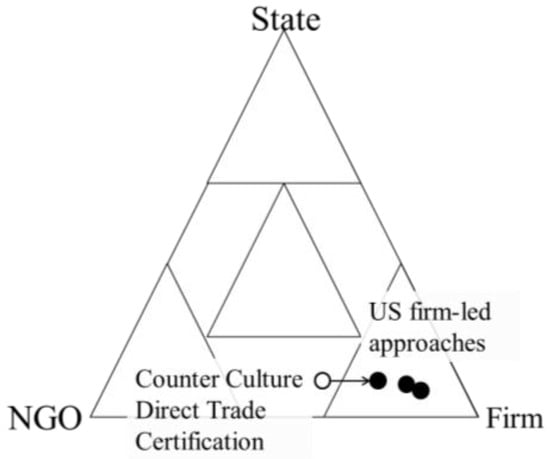

Monitoring practices in the US context have changed since 2015, most notably within Counter Culture, who ended their third-party certification, and now all founding firms self-report and release data to consumers. In 2015 Counter Culture Coffee was the only founding firm who collaborated with a non-governmental organization in monitoring their compliance with standards. This collaboration meant that Counter Culture represented a different regulatory approach than the other two US firms (Figure 3). By ending their third-party certification program, they shifted their regulatory approach to more strongly firm-led. All founding firms now monitor standard compliance internally and self-report compliance. Counter Culture Coffee argued in ending their direct trade certification scheme that monitoring should be more about data than verification (Table 6). In response to perceived co-optation, founding firms have emphasized backing up claims with data. Counter Culture claims that their move away from third-party verification is actually a move towards greater transparency. Data that in 2015 were released only about direct trade coffees is now provided for every coffee product and they now report on environmental conditions [52,56].

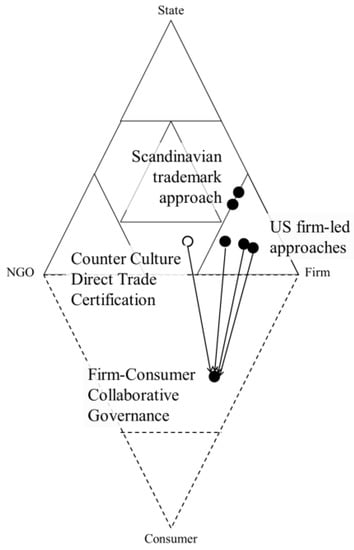

Figure 3.

Conceptual figure visualizing US direct trade regulatory standard-setting processes within regulatory space, using Abbott and Snidal’s [26] regulatory triangle. The black dots represent the three founding firm direct trade schemes in 2016 and are placed within the firm self-regulatory corner of the triangle. Collaboration between non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and firms played a strong role in Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification, which began in 2008, and is represented by an unfilled circle. The arrow represents the termination of the Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification in 2015 and Counter Culture’s subsequent shift to a strongly firm self-regulatory approach. Adapted from Abbott & Snidal [26] (p. 50) with permission from Princeton University Press.

4.1.5. Enforcement in the US

The US context demonstrates a lack of control over who can use the term direct trade and enforce common standards as there is no penalty for firms who misuse the term. Founding firms lack the power to enforce their own direct trade standards on other firms or prevent other firms from misusing the term. “You can call anything direct trade and you’re not going to get in trouble by anyone, in the legal sense” (CCC). Founding companies have also been reluctant to shame firms that they feel are misusing the term. “As a company [we] are not going to call out other companies and be like… ‘you’re saying direct trade and it doesn’t mean anything, it’s an empty statement’, which I personally would love to say” (CCC).

This use of the term direct trade by firms with weaker standards is a form of co-optation. “We [Stumptown] also call ourselves direct trade and I think the label has been co-opted by many people who are simply trying to greenwash” resulting in “very fair negative attention” which frustrated founding firms because “at the same time some really substantial and really positive work that’s been done behind that name [direct trade]” (ST). Co-optation in this situation means firms are calling themselves direct trade, yet using weaker standards than are the founding firms. While Counter Culture uses milder language their argument remains the same. Founding firms are concerned that the firms that developed weak direct trade schemes are allowed to continue to call themselves direct trade; there is nothing in the US context to stop other firms from misusing the term or to force adoption of stronger schemes.

Interviewees saw co-optation as enabled by the nature of direct trade and the “lack” of a “universal standard” (ST). The Stumptown interviewee believed factions within direct trade result from the conflicted nature of direct trade as “a sourcing model or… a model for merchandizing your coffee” noting that “merging those two” is “complicated” (ST). Counter Culture further adds that the misuse of direct trade is possible because “the definition of direct trade has never been codified in an international standard…” [50].

4.1.6. Mapping US Regulatory Structures

Based on the actors involved through these stages (Table 4), we mapped the regulatory standard-setting processes of these three firms’ voluntary schemes within the governance triangle (Figure 3). We argue that the US regulatory process now represents a strongly industry and firm self-regulatory structure. Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification used to collaborate with a non-governmental organization through third-party certification, but they now have an internally monitored scheme.

4.2. Development of Direct Trade in Scandinavia

We find that within the Scandinavian context, the use and content of direct trade voluntary schemes has remained stable for trademark-owning firms. Here, we briefly introduce the Scandinavian firms’ history with direct trade, examine the development of their direct trade schemes through regulatory standard-setting’s five stages, and then categorize the scheme’s regulatory approaches.

The Coffee Collective owners recognized both the promise and problems of US-based direct trade. They asked for permission to use direct trade from Intelligentsia, which was granted on the condition of protecting the “integrity” of the term (TCC). The interviewee presented obtaining the direct trade trademark in Denmark as protecting direct trade’s integrity from the problem of many direct trade definitions by different US roasters already developing in 2007. Any firm using the term direct trade in Denmark must be approved by The Coffee Collective; the Coffee Collective authenticates the compliance of other firms with their own trademarked direct trade scheme (TCC). Firms not verified or not in compliance with the Coffee Collective’s scheme are sent cease and desist letters (TCC).

Johan & Nyström was prevented from selling coffee marketed as direct trade in Denmark by the Coffee Collective; Johan & Nyström responded by applying for the trademark within Sweden (JN). This was problematic for them because they had seen direct trade schemes as open source (JN). According to the interviewee, Johan & Nyström are open to other firms using direct trade within Sweden, but they are not aware of any firms doing so and there is no authentication system for other firms in place as there is in Denmark (JN).

Koppi is a small, single-café independent roaster. In 2015 they called all of their coffee direct trade and described the sourcing policy entailed by that, but did not use a logo on packaging. Their scheme was informal, briefly describing their sourcing policy. They maintained the exact policy, but changed the name to “sustainable coffee trading” by the end of 2015 [36].

4.2.1. Agenda-Setting in Scandinavia

Agenda-setting for Scandinavian direct trade reflects the problems and opportunities of roasting firms. The desire for quality coffee is the primary motivation behind direct trade: “we wanted to form a transparent trade model that would guarantee us the best quality of produce, and guarantee the producers payment that meets that better quality” [46]. The problem as they saw it was “that coffee is normally being traded as a commodity,” (JN) and within commodity markets “nobody really cares first and foremost about quality” (JN). They pointed out “limitations” of Fair Trade in obtaining high-quality specialty coffee (TCC). Simultaneously, the specialty coffee market was critiqued for its “hollow communication” (TCC) that offered stories of farmers and claimed to pay good prices but offered no guarantees or data to back up those claims.

Scandinavian firms assert that direct trade schemes contribute to sustainability, although quality is the top priority. In describing why Johan & Nyström decided to work with direct trade, the interviewee talked “first and foremost about quality” and “secondly the sustainable aspects” related to producers. The interviewee also argued that the only way to consistently produce high-quality (good-tasting) coffee is in an “environmentally friendly” way, thus arguing high-quality direct trade coffee implies good environmental practices.

4.2.2. Negotiation of Standards in Scandinavia

Standards for Scandinavian direct trade were defined and continue to be negotiated internally within individual firms. The Coffee Collective’s standards were developed by the co-founders of the firm after requesting and receiving permission to use the term direct trade from Intelligentsia (TCC). The Johan & Nyström interviewee described the standard development process as “We’ve always been doing what we believe and just learning by heart.”

4.2.3. Implementation in Scandinavia

For trademark-owning firms, the usage of the direct trade schemes has remained stable between 2015 and 2016. The Coffee Collective interviewee discussed how clear and simple standards, which have not changed, allow consumers to recognize “what it [direct trade] signifies” (TCC). Direct trade communicates sourcing practices in a marketable form as it enables communication “on different levels of complexity” for consumers (TCC). This consistent usage of direct trade terminology and practice demonstrates how Scandinavian firms have maintained trademarked voluntary direct trade schemes that make sourcing practices marketable.

Koppi ceased to use the term direct trade, but maintains the same sourcing practices. In early 2015 Koppi used the term direct trade to describe their sourcing practices and coffee, but by late 2015 they had stopped using the term direct trade. This change is shown on their homepage where the header “Direct Trade Coffee” became “Sustainable Coffee Trading” [36] followed by the exact same text describing their sourcing practices. This demonstrates firms’ abilities to change their marketing strategy and thus their regulatory strategy by changing terminology, meanwhile maintaining the practices underlying it.

4.2.4. Monitoring in Scandinavia

Monitoring compliance is done internally within firms, although firms are increasingly reporting on their monitoring to consumers and other verification models are being considered. The Coffee Collective direct trade products have a high degree of transparency throughout the value chain. Each Coffee Collective direct trade product is traceable to the producer level, origin visits are reported within the firm’s blog and during the time of our study they decided to begin listing the price paid to producer on the packaging of each product as well as the product webpage (TCC), which provides data backing up their price standard.

Johan & Nyström’s reporting on fulfillment of standards is less systematic. Johan & Nyström direct trade products are traceable to a producer level, but precise numbers for price paid to producers, quality (cupping) score, date of latest origin visit and farm level sustainability policies are not available for all direct trade products. The interviewee recognized a need to systematize reporting and stated that there are active discussions about beginning an NGO-verified direct trade certification, with both processes modeled after Counter Culture Coffee (JN). The interviewee was not aware at the time that Counter Culture Coffee had abandoned their certification.

4.2.5. Enforcement in Scandinavia

The Coffee Collective and Johan & Nyström trademarked the term “direct trade” within their respective countries, giving them the power to enforce their own direct trade scheme definitions. Trademark ownership allows firms to enforce their own direct trade schemes via legal control over how the term may be used by other firms. The Coffee Collective interviewee stated they did this in order to protect the term direct trade so that consumers would know “what’s meant by it [direct trade]” (TCC). The Coffee Collective interviewee contrasted their level of control over direct trade usage with the situation in the US where direct trade has “a longstanding problem” of having “different meanings for every company” (TCC). Similarly, the Johan & Nyström interviewee stated the “big downside” of direct trade is that it “does not have any controlling agencies” and is therefore based on “how you choose to believe in the company that you buy from” (JN).

Firms within Sweden and Denmark that do not own the trademark have either had to conform to the trademark owner’s standards or cease to use the term direct trade. Within Denmark, firms can ask The Coffee Collective for permission to use the term direct trade. Firms will only receive permission if they agree to regularly submit documentation to The Coffee Collective to verify that they fulfill The Coffee Collective’s direct trade standards.

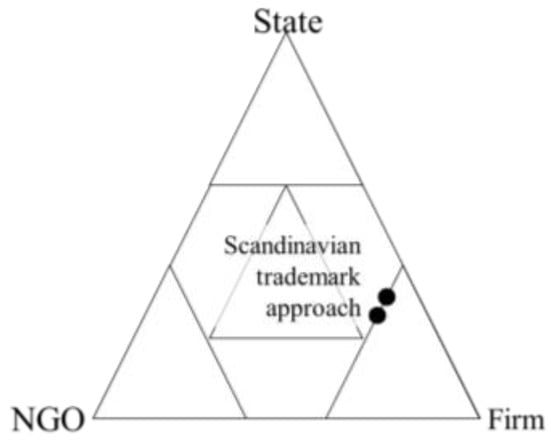

4.2.6. Mapping Scandinavian Regulatory Structures

Based on the actors involved through these stages, we mapped these Scandinavian schemes within the governance triangle (Figure 4). We argue that, for the trademark-owning firms, the regulatory standard-setting process of their direct trade schemes is on the boundary between firm self-regulation and firm-state collaborative governance. While the regulatory process was led by firms, firms strategically brought in state actors who control decision-making power at particular stages of the regulatory standard-setting process. Firms did this in order to pursue a strategy of trademarking.

Figure 4.

Conceptual figure uses Abbott and Snidal’s [26] regulatory triangle to map regulatory standard-setting process of Swedish and Danish schemes. Two firms pursued a trademarking approach in their respective countries so their processes were primarily firm-led yet strategically involved state actors, particularly within the standard-negotiation and enforcement stages. The third firm’s scheme (Koppi) is not included due to lack of data and ceasing to use direct trade schemes. Adapted from Abbott & Snidal [26] (p. 50) with permission from Princeton University Press.

Trademarking in this Scandinavian context was done in a particularly powerful way. Scandinavian firms trademarked the broad concept of direct trade, rather than a narrow firm- or initiative-specific trademark. In other words, The Coffee Collective broadly trademarked “direct trade” and not the narrower “The Coffee Collective direct trade.” This broad trademarking differs from narrow trademarking seen in the US context, such as Counter Culture Direct Trade Certification, which is trademarked but narrowly refers to the scheme and not to all instances of direct trade. The Scandinavian broad trademarking strategy also differs from the use of trademarks seen in firm self-regulatory schemes like the Sustainable Forestry Initiative [26] (Figure 2). The difference between narrow and broad trademarks is the difference between narrowly trademarking the “Sustainable Forestry Initiative” and broadly trademarking the term “sustainable forestry” itself.

Trademarking and, specifically, broad trademarks played a major role in the development of direct trade as a voluntary scheme in Scandinavia, particularly within the stages of standards negotiation and enforcement.

Broad trademarks enable greater control by trademark-owning firms through enforcement in a wider array of cases. Through a broad direct trade trademark, trademark-owning firms may control the usage of the term direct trade within their country regardless of whether use is related to their own trademarked scheme, the development of a different direct trade scheme or even use of the term direct trade as a concept. By contrast, narrow trademarks would only enable control over the usage of their individual voluntary scheme. This is a powerful position for trademark-owning firms as direct trade was already a popular term in the coffee industry internationally. Trademarks are a powerful regulatory tool of the state and were strategically used by Scandinavian firms in the development of their direct trade schemes.

We consider this regulatory approach to be more than firm self-regulation because of the important decision-making power held by state actors. Trademarking is not a regulatory strategy a firm could pursue without some level of direct involvement of state actors and broad trademarking greatly enhances the importance of state actor involvement. State actors directly participated through approving trademark applications. These decisions of state actors to grant broad direct trade trademarks enable trademark-owning firms to enforce their definitions, again mediated through state actors who ultimately decide whether infringement occurred and determine penalties for infringement.

The Scandinavian direct trade schemes were positioned relative to other schemes in the regulatory triangle in a border area between firm and state collaborative governance and firm self-regulation. State actor direct participation and decision-making power was important in the development of the Scandinavian schemes, but was not seen in the US schemes, which now clearly represent firm self-regulatory schemes. On the other hand, firm and state collaborative governance schemes such as the UN Global Compact Caring for Climate [26] (Figure 2) demonstrate a more active role for state actors than the Scandinavian schemes. This border area between firm self-regulation and firm and state collaborative governance where we position the Scandinavian trademarked schemes is an area that tends to be empty of schemes in classifications [26,27]. Due to the direct and important participation of both firm and state actors in broad trademark schemes and the comparison to other schemes positioned within the triangle, we determined that the Scandinavian schemes should be positioned in this border area between firm self-regulation and state and firm collaborative governance.

5. Discussion

Direct trade in the US and Scandinavia followed different regulatory approaches leading to different outcomes. In the US, direct trade changed rapidly and now represents only firm self-regulatory approaches, while in Scandinavia state actors have played a passive but influential role in regulatory governance. Founding US firms have backed away from direct trade, while Scandinavian firms’ trademarked direct trade schemes have remained stable. In this section, we discuss the implications of this direct trade case in terms of how regulatory standard-setting processes and structures contributed to differing outcomes in US and Scandinavia, focusing on what we can learn from this case about the development of voluntary sustainability schemes coming from various regulatory approaches involving firms.

5.1. Relevance of Firm-Framed Agenda

Agenda-setting is problematic for direct trade because the lack of representation of other actors within this stage led to the development of standards that prioritize the needs of roasting firms. This led to the development of a voluntary scheme motivated primarily by narrow vested business interests of capture rather than public good [57]. For the six firms we studied, standards were developed based primarily on the desire for consistent supply of high-quality coffee. Through this regulatory agenda the scheme was optimized for this particular business concern rather than to maximize livelihood improvements, to target the most vulnerable producers, to protect areas with high biodiversity, to reduce negative environmental impacts or other public good concerns. This is problematic because the scheme is marketed in part on its contribution to the public good, although incentives within this voluntary scheme are not aligned to produce an optimal result for public good.

5.2. Rapid Change of Firm Negotiated Standards

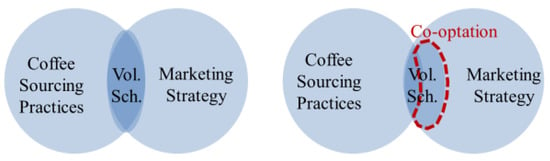

The negotiation of standards by individual firms within a firm-led regulatory process allowed standards to change rapidly in the US. This process goes against established good practices for the development of a credible sustainability label [58], such as having multi-stakeholder decision-making groups or building on existing standards systems. This level of individual firm control, flexibility of standards, and low entry costs may be part of the appeal of such schemes for firms. The lack of universal standards allowed for negotiation of standards within individual firms, creating conditions in which standards could be weakened by individual firms and ultimately contributing to co-optation in the US context. Weakening of standards has also been identified as the central mechanism in the co-optation of Fair Trade [59]. Co-optation of direct trade voluntary schemes refers to the accusation that new direct trade schemes have weaker standards and are more about marketing than guaranteeing good sourcing practices (Figure 5). Similarly the use of direct trade as a marketing strategy without being supported by a voluntary scheme is increasingly common, but perceived by those using direct trade voluntary schemes as co-optation of the term direct trade.

Figure 5.

Conceptual figure depicts co-optation in the context of direct trade voluntary schemes, shortened to Vol. Sch. in the figure. Co-optation in this context refers to direct trade voluntary schemes that use direct trade to market coffee with weaker guaranteed coffee sourcing standards.

5.3. Increasing reliance on consumer as monitor

In response to the co-optation of direct trade in the US, founding firms shifted their strategy from a voluntary scheme toward greater transparency by increasing the amount of data provided to consumers, which implies a large and increasing role for consumers within regulatory governance. All firms discussed the importance of providing data to back up claims specifically to consumers. Figure 6 visualizes how Counter Culture might conceptualize the end of third-party certification as a move toward consumer regulated markets, rather than greater firm control. Other US firms might also present their approaches not as self-regulation, but as developing a greater role for consumers in regulatory governance. We argue this creates greater responsibilities for consumers because data release without third-party certification in effect makes consumers responsible for monitoring released data and enforcement through purchasing practices.

Figure 6.

Conceptual figure showing Abbott and Snidal’s governance triangle with consumers added as a main actor in regulatory governance for the case of direct trade coffee. US direct trade schemes are represented as moving into a regulatory approach involving firm and consumer collaboration because they are trying to involve individual consumers in monitoring and enforcement of standards through direct release of data to consumers. Adapted from Abbott & Snidal [26] (p. 50) with permission from Princeton University Press.

We argue these additional consumer responsibilities will not improve regulatory governance. The data released by firms to back up claims tend to be complex, requiring analytical context and technical competencies to be meaningful, which few individual consumers likely have. Data are provided by firms because firms want consumers to distinguish between strong and weak schemes, yet co-optation was possible in part due to consumer failure to distinguish between different schemes. Research on Fair Trade, a well-known voluntary regulatory certification scheme, has shown that most consumers feel overburdened by detailed information and have difficulty distinguishing between Fair Trade labels [60]. The informality and larger number of different schemes would make distinguishing between direct trade schemes even more difficult for consumers.

Co-optation can cause consumer confusion through changing standards. This difficultly of staying up-to-date with shifting standards leads to uninformed purchasing decisions, which undermines the logic of sustainable consumption. This is problematic because it means that a trade model based on transparency and harnessing the power of consumers to improve business practices through purposeful purchasing has led to a situation in which it is difficult for consumers to make informed purchasing decisions. We therefore argue that the individual consumer may not be an appropriate actor for such monitoring and evaluation responsibilities in a regulatory standard-setting process.

5.4. Lack of Enforcement and an Environment for Co-Optation

In the US context, lack of enforcement contributed to an environment that made co-optation possible. In competition between firms, strong standard direct trade firms could not stop weak standard firms from calling themselves direct trade. An example of this weak standard direct trade could be Target’s in-house brand Archer Farms. In 2015 and 2016 Archer Farms direct trade products were not all traceable to their specific origins, not even to a country level, and products from different regions used the same film clip of the same producer [61,62]. In July 2016 Target announced a redesign and expansion of Archer Farms direct trade [63] so there is now traceability for some but not all direct trade products [64], but online packaging and product webpages still do not state explicit standards related to price, quality, or traceability or include a link to more information about their direct trade scheme as of November 2016 [64]. Target reaches more consumers than the founding firms through sheer size, giving it a powerful position communicating direct trade to consumers. Target currently has 1802 locations [65]. Only state actors have the power to penalize firms and in the US context there are not penalties for misusing the direct trade scheme.

We consider the US context to represent failure to self-regulate because it represents a strongly firm self-regulatory approach in contrast to the Scandinavian schemes in which state actors were strategically introduced into regulatory governance by firms. The Scandinavian context demonstrates the possibility to maintain a stable voluntary scheme in terms of content and marketability by defining and enforcing the scheme and use of the concept through a broad trademark. The outcome in the Scandinavian context is not an example of successful industry self-regulation (Figure 4), but rather demonstrates the power of involving other actors within regulatory governance, in this case state actors through trademarking. State actors are powerful because they can issue penalties, as seen in the use of the legal system with trademarking. Although the role of state actors was largely passive in terms of development of standard content, it still had a major impact on the development of the scheme through decision-making power in the negotiation and enforcement stages. Of course, there are other differences beyond trademarking between the US and Scandinavian contexts in the size and competitiveness of the specialty coffee markets.

However, a trademarked voluntary scheme presents a unique set of problems for negotiating standards and enforcement. Namely, the standards within trademarked voluntary schemes are defined by whoever is granted the trademark, generally meaning whoever first applies for the trademark. The first firm to apply for the trademark is not necessarily defining the best or strongest sustainability standards for their voluntary sustainability scheme. If the trademark were granted to a weak scheme, then the weak scheme could enforce its definition on stronger schemes that could be forced to either adopt the weak scheme standards or change the name of their scheme.

5.5. Regulatory Approach

There is sound logic behind having a more open regulatory approach that allows change within voluntary schemes and enables social innovation. The founders of direct trade in the US seem to have envisaged a more open approach to voluntary schemes than either formal certification or trademarked schemes. From the interviews, it would appear that the original creators of the direct trade schemes envisaged that social innovation could be furthered through communities of practice in direct trade and social learning to further the development of the schemes. It is likely that the founders wanted to support the shared learning and innovation that comes from informal communities of practice across the industry [66] and small groups crossing organizational boundaries [67] in this case, developing social innovation [68] aimed at creating new ways of improving coffee quality and producer livelihoods. Furthermore, past experience with Fair Trade seems to have caused concern for the roasters about how well the system works in different contexts, a justifiable concern [69,70,71]. Given the potential benefits of social innovation through communities of practice and social learning, it is reasonable that a more open approach to voluntary schemes was pursued.

The downside of the more open approach seen in this case is the possibility of co-optation. Co-optation undermines sustainable production by incentivizing lower standards and undermines sustainable consumption by making informed purchasing decisions difficult for consumers. We found that actor structures in regulatory governance may influence co-optation. In particular, state actors are able to penalize and thus enforce schemes in a way that firms were not. Higher levels of involvement of state or non-governmental organization actors in the agenda-setting stage would mean greater representativeness, which could lead to schemes’ greater prioritization of public good. Private interests are important as voluntary schemes depend on firms to decide to be involved. Our case supports the argument of Abbott and Snidal [26] that no single actor—in our case firms—has all the necessary competencies to successfully navigate every stage of the regulatory standard-setting process, and therefore we argue for more collaborative regulatory governance structures to promote more sustainable production and consumption.

6. Conclusions

We found that direct trade as a voluntary regulatory scheme was an attempt to market and codify good sourcing practices, but that founding firms began distancing themselves from the term due to co-optation, in which direct trade came to represent more of a marketing strategy than the substantive sourcing standards of a voluntary sustainability scheme. Direct trade is not working well in the US; it is more beneficial to those that co-opted it than to those that take it most seriously. The open industry self-regulatory standard-setting pathway followed by the US firms was intended to foster communities of practice for social innovation but created an environment in which co-optation was enabled through the re-negotiation of standards without the power of enforcement. The firms we studied reacted to co-optation by releasing large amounts of data, effectively expecting consumers to act as monitors and enforcers of standards, but we argue this will not improve regulatory governance. Scandinavian firms maintained stable trademarked voluntary schemes. A trademarked scheme’s regulatory strategy benefits stability and rewards the first scheme to be granted trademark, which is not necessarily the best scheme. Both the US and Scandinavian contexts demonstrate the weakness of firm-led agenda-setting with the creation of a schemes optimized for firms’ private interest, in this case concerns for taste quality, rather than public interest in sustainable development. The examination of direct trade has demonstrated the limitations of firm and industry self-regulatory standard-setting processes, particularly in terms of developing relevant regulatory agendas, the threat of co-optation and the potential problem of consumer-based regulatory governance. These discussions are relevant to other voluntary schemes heavily involving firms in regulatory standard-setting and to trade models based on transparency to consumers.

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly thank the interviewees who kindly shared their time and expertise. The authors would like to thank Lennart Olsson at LUCSUS for comments on earlier drafts of this article. This research was supported by Lund University Centre of Excellence for Integration of Social and Natural Dimensions of Sustainability (LUCID), a Linnaeus Centre funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas.

Author Contributions

Finlay MacGregor conceived of the idea of the study, designed the study, collected the data, analyzed the data, wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design, analysis and interpretation of data, and to editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsor had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References and Note

- General Assembly, Resolution 70/1 Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1, United Nations, 2015. Available online: http://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 27 October 2016).

- Garnett, T.; Appleby, M.C.; Balmford, A.; Bateman, I.J.; Benton, T.G.; Bloomer, P.; Burlingame, B.; Dawkins, M.; Dolan, L.; Fraser, D.; et al. Sustainable Intensification in Agriculture: Premises and Policies. Science 2013, 341, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Geibler, J. Market-based governance for sustainability in value chains: Conditions for successful standard setting in the palm oil sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, C.; Gale, F.; Haley, D. Setting the Standard: Certification, Governance, and the Forest Stewardship Council; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Abbott, K.; Andresen, S.; Bäckstrand, K.; Bernstein, S.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H.; Cashore, B.; Clapp, J.; Folke, C.; et al. Transforming governance and institutions for global sustainability: Key insights from the Earth System Governance Project. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulponi, L. Private voluntary standards in the food system: The perspective of major food retailers in OECD countries. Food Policy 2006, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Bloom, G.; Ely, A.; Nightengale, P.; Scoones, I.; Shah, E.; Smith, A. Understanding Governance: Pathways to Sustainability; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.A. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework. Gov. Int. J. Policy Adm. Inst. 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, G. Assessing Certification as Governance: Effects and Broader Consequences for Coffee. J. Environ. Dev. 2010, 19, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P. Assessing effectiveness of governance approaches for sustainable consumption and production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, C.; Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Shaping Sustainable Value Chains: Network Determinants of Supply Chain Governance Models. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Zhang, H. Voluntary Certification of Agricultural Products in Competitive Markets: The Consideration of Boundedly Rational Consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, D.; Koekoek, F.J. The State of Sustainable Coffee: A Study of Twelve Major Markets; IISD, UNCTAD, ICO: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, J.; Manning, S.; von Hagen, O. The Emergence of a Standards Market: Multiplicity of Sustainability Standards in the Global Coffee Industry. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 791–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Public Information, Responsible Consumption & Production: Why it Matters. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/16-00055L_Why-it-Matters_Goal-12_Consumption_2p.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2016).

- Bacon, C.M.; Mendez, V.E.; Gomez, M.E.F.; Stuart, D.; Flores, S.R.D.; Ernesto Méndez, V.; Gómez, M.E.F.; Stuart, D.; Flores, S.R.D. Are Sustainable Coffee Certifications Enough to Secure Farmer Livelihoods? The Millenium Development Goals and Nicaragua ’ s Fair Trade Cooperatives. Globalizations 2008, 5, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, C.; Läderach, P.; Ovalle Rivera, O.; Kirschke, D. A bitter cup: Climate change profile of global production of Arabica and Robusta coffee. Clim. Chang. 2015, 129, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovalle-Rivera, O.; Läderach, P.; Bunn, C.; Obersteiner, M.; Schroth, G. Projected shifts in Coffea arabica suitability among major global producing regions due to climate change. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzen, M.; Moran, D.; Kanemoto, K.; Foran, B.; Lobefaro, L.; Geschke, A. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature 2012, 486, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, P. To Burundi and Beyond for Coffee’s Holy Grail; New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. F8. [Google Scholar]

- Germain, S. Direct Trade: Going Straight to the Source. Available online: http://www.scaa.org/chronicle/2012/02/14/direct-trade-the-questions-answers/ (accessed on 5 December 2016).

- Mol, A.P.J.; Oosterveer, P. Certification of markets, markets of certificates: Tracing sustainability in global agro-food value chains. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12258–12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.; Snidal, D. The Governance Triangle: Regulatory Standards Institutions and the Shadow of the State. In The Politics of Global Regulation; Mattli, W., Woods, N., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 44–88. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.W. The transnational regime complex for climate change. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, L. The Direct Effect: The Opportunities and Challenges of Direct-Trade Coffee. Imbibe Magazine: Portland, OR, United States, 2014. Available online: http://imbibemagazine.com/direct-trade-coffee/ (accessed on 13 November 2015).

- Macatonia, S. Going Beyond Fair Trade: The Benefits and Challenges of Direct Trade; Guardian: London, UK, 2013; Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/direct-trading-coffee-farmers/ (accessed on 13 November 2015).

- Weissman, M. God in a Cup: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Coffee; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Counter Culture Coffee Website. Available online: http://www.counterculturecoffee.com/ (accessed on 7 April 2015 & 5 September 2016).

- Intelligentsia Coffee Inc. Website. Available online: http://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/ (accessed on 1 April 2015 & 6 September 2016).

- Stumptown Coffee Roasters Website. Available online: http://www.stumptowncoffee.com/ (accessed on 2 April 2015 & 6 September 2016).

- The Coffee Collective Website. Available online: http://coffeecollective.dk/ (accessed on 16 March 2015 & 6 September 2016).

- Johan & Nyström: Coffee Roaster & Tea Merchant Website. Available online: http://www.johanochnystrom.se/en/ (accessed on 16 January 2015 & 5 September 2016).

- Koppi: Fine Coffee Roasters Website. Available online: http://www.koppi.se/ (accessed on 16 January 2015 & 5 September 2016).

- Koppi Website. Available online: http://www.koppi.bigcartel.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2016).

- Zell, D. Open Letter from Doug Zell. Available online: http://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/content/open-letter-doug-zell (accessed on 29 November 2016).

- Stumptown Coffee Roasters. A Note about Peet’s Webpage. Available online: https://www.stumptowncoffee.com/blog/a-note (accessed on 11 November 2016).

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; Version 10; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Doncaster, Australia, 2014.

- Stumptown Coffee Roasters. Direct Trade Webpage. Available online: http://stumptowncoffee.com/education-overview/direct-trade (accessed on 16 January 2015).

- Counter Culture Coffee. Direct Trade Certification Webpage. Available online: https://counterculturecoffee.com/sustain/direct-trade-certification (accessed on 16 January 2015).

- Intelligentsia Coffee Inc. Direct Trade: How We Buy Coffee Webpage. Available online: http://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/content/direct-trade (accessed on 16 January 2015 & 6 September 2016).

- Johan & Nyström. Direct Trade Webpage. Available online: http://johanochnystrom.se/en/about-us/our-coffee/direct-trade/ (accessed on 16 January 2015 & 5 September 2016).

- Stumptown Coffee Roasters. Our Story Webpage. Available online: https://www.stumptowncoffee.com/our-story (accessed on 6 September 2016).

- The Coffee Collective. About—Direct Trade Wepage. Available online: https://coffeecollective.dk/about/ (accessed on 16 January 2015 & 6 September 2016).

- Intelligentsia Coffee Inc. Learn & Do: Community—Direct Trade Webpage. Available online: https://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/learn-do/community/intelligentsia-direct-trade (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Intelligentsia Coffee Inc. Extraordinary Coffee Workshop Webpage. Available online: https://www.intelligentsiacoffee.com/learn-do/community/extraordinary-coffee-workshop (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Prince, M. Counter Culture’s Direct Trade Certification Program. Available online: http://www.coffeed.com/viewtopic.php?f=19&t=2129 (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Counter Culture Coffee. #CCCTHRU: Know Your Coffee, Durham, NC, United States, Unpublished work. 2015.

- Counter Culture Coffee. Sustainability Reports Webpage. Available online: https://counterculturecoffee.com/sustainability/reports (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Counter Culture Coffee. Purchasing Principles Webpage. Available online: https://counterculturecoffee.com/sustain/purchasing-principles (accessed on 5 September 2016).

- Stumptown Coffee Roasters. Coffee & Espresso: Shop Stumptown Coffee Webpage. Available online: https://www.stumptowncoffee.com/coffee (accessed on 6 September 2016).

- Stumptown Coffee Roasters. Direct Trade Webpage. Available online: http://buy.stumptowncoffee.com/direct-trade.html (accessed on 1 April 2016).