Abstract

Arenaviruses include lethal human pathogens which pose serious public health threats. So far, no FDA approved vaccines are available against arenavirus infections, and therapeutic options are limited, making the identification of novel drug targets for the development of efficacious therapeutics an urgent need. Arenaviruses are comprised of two RNA genome segments and four proteins, the polymerase L, the envelope glycoprotein GP, the matrix protein Z, and the nucleoprotein NP. A crucial step in the arenavirus life-cycle is the biosynthesis and maturation of the GP precursor (GPC) by cellular signal peptidases and the cellular enzyme Subtilisin Kexin Isozyme-1 (SKI-1)/Site-1 Protease (S1P) yielding a tripartite mature GP complex formed by GP1/GP2 and a stable signal peptide (SSP). GPC cleavage by SKI-1/S1P is crucial for fusion competence and incorporation of mature GP into nascent budding virion particles. In a first part of our review, we cover basic aspects and newer developments in the biosynthesis of arenavirus GP and its molecular interaction with SKI-1/S1P. A second part will then highlight the potential of SKI-1/S1P-mediated processing of arenavirus GPC as a novel target for therapeutic intervention to combat human pathogenic arenaviruses.

1. Introduction

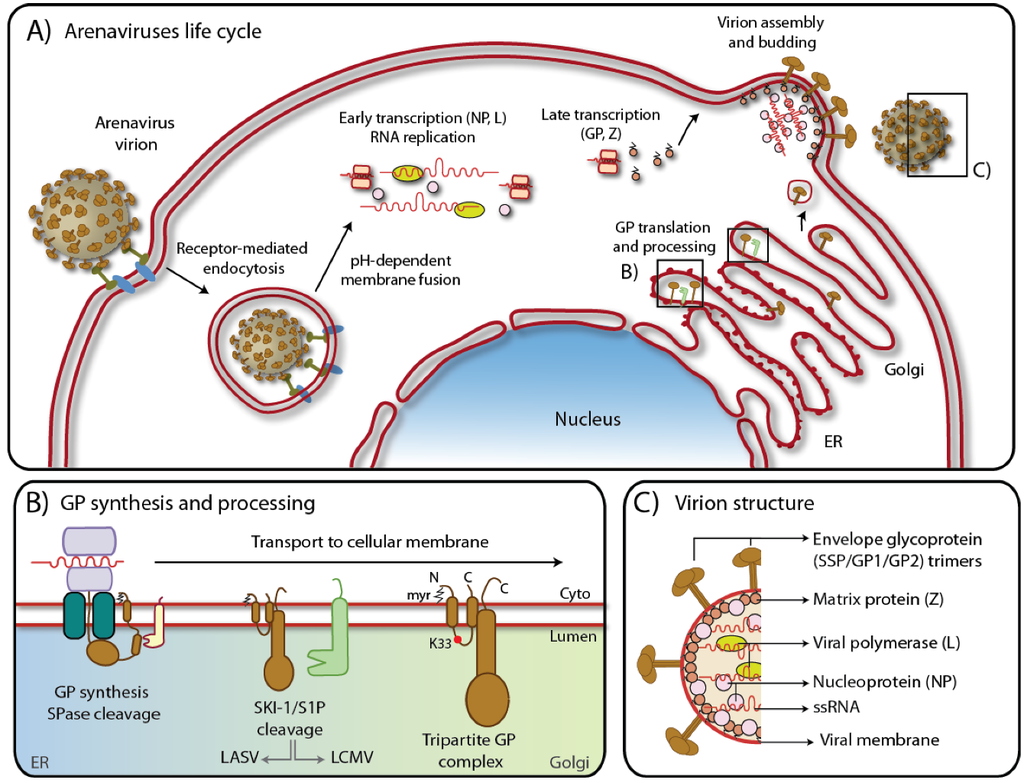

2. The biosynthesis of the glycoprotein precursor

The envelope glycoprotein of Arenaviruses is synthesized as a polypeptide composed of an N-terminal stable signal peptide (SSP) and the SSP-containing GPC. Upon cleavage by cellular signal peptidases in the ER, GPC is further processed by the cellular proprotein convertase (PC) Subtilisin Kexin Isozyme-1 (SKI-1)/Site-1 Protease (S1P) into the GP1 and GP2 subunits [39,40,41] (Figure 1B). Post-translationally, the SSP acquires a myristoyl moiety at a Gly residue at position 2 [42] while the GP1/GP2 complex undergoes extensive N-glycosylation at multiple sites [43]. The interactions among the three subunits of the envelope glycoprotein, SSP, GP1, and GP2 are complex and not yet fully understood.

2.1. The signal peptide is not degraded and forms a stable tripartite complex with GP1/GP2

The role of the stable signal peptide (SSP) of arenaviruses has been comprehensively reviewed by a recent excellent review [44]. The arenavirus SSP has several unique characteristics in addition to its conventional function of targeting the nascent GPC polypeptide into the ER. Processing of nascent GPC by cellular signal peptidases occurs co-translationally and results in an unusually long (58 amino acids) signal peptide which does not undergo immediate degradation, but has a half-life of > 6h [45,46,47]. Standard signal peptides contain only one hydrophobic transmembrane domain but arenavirus SSP possess two hydrophobic regions separated by a hydrophilic loop containing a conserved positively charged Lys residue at position 33 (K33) [45]. Analysis of the JUNV SSP membrane topology revealed that both hydrophobic domains span the membrane with the N- and C-termini located in the cytosol and K33 facing the lumen/extracellular space [38]. SSP K33 is an important determinant for the pH-dependent fusion of the glycoprotein with the host cell membrane [48,49]. The SSP associates with the GP2 subunit, involving a Zn-binding motif [42,50,51,52,53]. Interestingly, recently discovered small molecule inhibitors of arenavirus cell entry target the molecular interface between SSP and GP2 [54], resulting in inhibition of pH-induced fusion. Lack of SSP myristoylation also affects fusion but not the formation of the SSP/GP1/GP2 complex [42]. The unusual arenavirus SSP is strictly required for proteolytic maturation of the GPC precursor [43,53]. Trans-complementation and interchanges among arenavirus GPC SSPs [55] are allowed but arenavirus SSP replacement with a generic signal peptide is not. In the case of JUNV GPC, the SSP was shown to be necessary for the GP to exit the ER by masking an ER-retention motif located on GP2 [53]. Lack of SSP would prevent the GP from being transported to the Golgi where SKI-1/S1P resides, thus averting maturation.

2.2. Glycosylation of the GP1/GP2 complex

N-linked glycosylation is an essential process to help correct folding and intracellular transport of viral envelope GPs [56]. Analysis of the potential sites of N-glycosylation on arenavirus GPs revealed 4 conserved residues located on GP2 (with the exception of LCMV, DANV and LUJV), whereas the predicted sites on GP1 are multiple and show a lower degree conservation [43,57]. Recent studies showed that of the nine potential N-glycosylation sites of LCMV GPC, all the available sites were used on GP1 and two of three on GP2 [57]. All predicted N-glycosylation sites on LASV GPC (7 on GP1 and 4 on GP2) are used [43]. Mutation of some N-glycosylation sites prevented proteolytic processing, whereas others were dispensable for GPC cleavage. The role of N-glycosylation for GPC maturation and transport is complex and may be different according to the arenavirus species. Eichler et al. demonstrated that uncleaved LASV GPC present on the cell-surface remain EndoH sensitive, indicating the presence of mannose glycans, but absence of hybrid and complex N-glycans. Based on this result, cleavage of LASV GPC into GP1 and GP2 was suggested to be required for complex N-glycosylation upon exit from the ER [43]. Conversely, LCMV GPC cleavage was shown to occur after trimming of the mannose-rich N-glycans and their extension to complex N-linked sugars.

2.3. GPC is cleaved by the cellular protease SKI-1/S1P

The majority of enveloped viruses shares a common mechanism of maturation based on the priming of their envelope GP precursors by host proteases in order to attain fusogenic properties [58,59,60,61,62,63]. Cleavage releases the fusion peptide, a hydrophobic stretch of 20-30 amino acids, which is able to act as an anchor in the target membrane, lowering the rupture tension of the lipid monolayer and promoting a negative curvature to ultimately allow joining the host-derived and virus membranes [64]. This strategy allows the envelope GP subunits to fold and oligomerize prior to assume, upon cleavage, a metastable conformation which undergoes drastic changes following receptor binding and/or drop of pH. The envelope precursor processing is also a mechanism to efficiently generate infectious particles since incorporation of mature envelope GPs is in general preferred over the uncleaved and fusion-incompetent ones [40,65,66]. Relative tissue abundance of the specific enzyme responsible for the processing contributes to determine the tropism of the enveloped virus whose growth may therefore be limited to specific cells/organs.

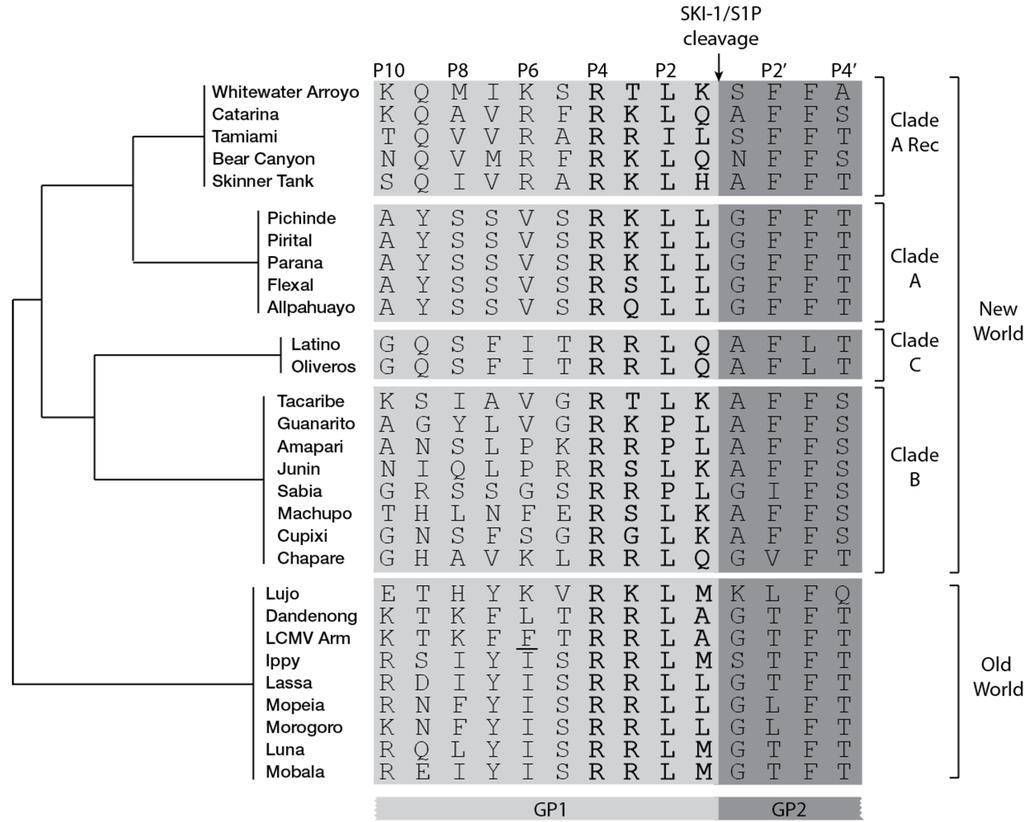

The arenavirus GPC is post-translationally cleaved at the highly conserved motif RX(hydrophobic)X↓, where X is any amino acid and hydrophobic is preferentially Leu (Figure 2) [67]. In the absence of GP1, GP2 spontaneously forms a trimer, in which each subunit is folded in a “hairpin”-like postfusion conformation of class I viral fusion proteins [68,69]. SKI-1/S1P is responsible for the cleavage of the GPCs of both OW [40] [39] and NW [41] arenaviruses. SKI-1/S1P belongs to the proprotein convertase (PC) family, which counts 9 members, so far, including 7 basic PCs (furin, PC1/3, PC2, PC4, PACE4, PC5/6, and PC7) and the self-inhibited proprotein convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 (PCSK9). Differently from the other active members of PCs that cleave after clusters of (multi)basic motifs, the peculiar consensus sequence of SKI-1/S1P contains hydrophobic residues [70,71]. The protease is synthesized as an inactive zymogen that requires auto-processing of the N-terminal pro-domain at the B/B’ (RKVF↓RSLK↓) and C (RRLL↓) sites to attain full maturation [72]. In the cell, mature SKI-1/S1P localizes in the early Golgi, where the majority of its cellular substrates are cleaved, but also in the lysosomes and in the extracellular space, in a shed enzymatic form [71].

The biological activities of SKI-1/S1P are numerous and affect essential cellular functions. Among the best characterized SKI-1/S1P substrates are the Sterol Regulating Element Binding Proteins (SREBPs), transcription factors activated via limited proteolysis to control cell lipid homeostasis [72,73]. In vivo studies suggest that blocking SKI-1/S1P activity may be an alternative approach to lower plasma cholesterol [74]. The SREBPs activation process, common to other transcription factors, is known as regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP) and involves translocation to the Golgi compartment upon specific stimuli and subsequent proteolytic cleavage. Member of the CREB/ATF family of transcription factors including ATF6 [75] CREBH, Luman, CREB3L4, CREB4, and OASIS, have been identified as SKI-1/S1P substrates, related to the unfolded protein response (UPR) [76]. Very few cellular examples of non-transcription factor proteins are known to be cleaved by SKI-1/S1P. Examples are N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase, a key enzyme for the sorting of proteins into the lysosomal compartment [77], pro-brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [78] and repulsive guidance molecule (RGMa) [79]. SKI-1/S1P cleaves proBDNF within its pro-domain but the biological significance of this processing is not known. Similarly, RGMa processing by SKI-1/S1P seems to be required although the cleavage sites have not yet been identified. The protease was also found to be crucial for normal bone and cartilage formation [80,81], and mice coat pigmentation [82], but the substrates involved in these biological processes are still to be discovered. In mice, SKI-1/S1P K.O. shows a lethal phenotype with the embryos dying at an early developmental stage [83]. Even incomplete inhibition of SKI-1/S1P causes severe effects: homozygosity for the woodrat mutation, which shows partial loss of enzyme function, leads to hypersensitivity to dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis [84], and causes enhanced embryonic mortality [85].

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequence aligment of arenaviruses GPC residues surrounding the cleavage site (indicated by arrow). Residues of mature GP1 are in light gray while residues of mature GP2 are in darkgray. The four amino acids of clevage site motif are in bold. The schematic cladogram indicates the phylogenetic relationships between the viral clades is shown on the right. The LCMV cl13 strain amino acid variant F260L is underlined. Accession numbers are in supplementary table 1.

In contrast to cellular substrates of SKI-1/S1P that are processed in the median Golgi, LASV GPC is cleaved in the ER/cis-Golgi and LCMV GPC in a late Golgi compartment [39,71,86]. The way the virus is able to hijack active SKI-1/S1P in these specific subcellular compartments is not known. However, switching the LCMV GPC RRLA↓ motif into RRLL↓ present in LASV GPC re-direct the cleavage of the latter from a late Golgi compartment to the ER/cis-Golgi. In contrast, a LASV GPC chimera carrying the LCMV “RRLA↓” motif, is not cleaved despite following normal sorting to the plasma membrane [86]. Thus, available evidence suggests that the specific amino acid sequence at the cleavage site may contribute to the processing at specific sub-cellular localizations. No clear information is currently available about the maturation of other arenavirus GPCs, although some evidences suggest JUNV GPC processing in the Golgi [87].

A characteristic common to most arenavirus GPCs [67] (Figure 2) is the striking resemblance of their processing sites to SKI-1/S1P auto-cleavage motifs: while African OW and NW clade B arenavirus GPCs mimic the C-auto-processing site “RRLL↓”, NW arenavirus GPCs resemble the B-auto-processing site “RSLK↓”. The mimicry indicates convergent evolution towards a common maturation mechanism resembling SKI-1/S1P auto-processing, which is not evident in other cellular SKI-1/S1P substrates. The advantage may account for the virus’ ability to avoid interference with cellular functions in order to persist in the reservoir rodent host. Accordingly, the SKI-1/S1P-dependent activation of ATF6 is normally induced by LCMV GPC during acute infection. As soon as GPC expression is down-regulated during the transition from acute to persistent infection [88], the UPR response triggered by ATF6 disappears [89]. However, the reason behind the selective association “RRLL↓”-OW arenavirus and “RSLK↓”-NW arenavirus are currently unclear.

Specific GPC residues surrounding the cleavage site were shown to influence maturation. An F259A point mutation at P7 position of LCMV GPC greatly impairs processing [39]. Analysis of peptides mimicking the cleavage site of LASV GPC revealed that cleavage efficiency may be negatively affected by the presence of a non-aromatic residue at P7 position, indicating the presence of an unusually large catalytic pocket able to accommodate residues distal from the actual processing site [70]. Indeed, in comparative studies, the YISRRLL↓ sequence mimicking the cleavage site of LASV GPC is the best substrate to assess in vitro SKI-1/S1P enzymatic activity [77,78,90].

The N-terminus of LASV GP2 contains two stretches of highly conserved hydrophobic amino acids. Alanine scanning of the N-terminal 260-266 and 276-298 sequences revealed that maturation of the envelope GPC does not occur in presence of single point mutations at positions 260, 261, 262, 280, 284, 285, 286, 292, and 293, despite GPC folding and reaching the plasma membrane [91]. Indeed, GPC cleavage is not essential for transport to the plasma membrane, yet only the fully mature complex is found on budding particles [66,72,74]. A similar effect is observed in the case of the LASV GPC N-glycosylation mutants S367A and S375A, which are transported normally to the cell surface but fail to be cleaved [43]. LASV GP1 glycosylation at position 81, 91, 101, and 121 are required for proteolytic processing but not cell surface localization. In contrast, mutations that abolish normal glycosylation at positions 111, 169, and 226 are not crucial for the precursor maturation [43]. The data at hand thus suggest that SKI-1/S1P-mediated processing may require specific tertiary/quaternary structures of the GP1/GP2 complex that are disrupted by specific point mutations deletions.

A large body of evidence indicate a crucial role of the cytoplasmic domains of viral envelope GPs in assembly, fusogenicity, and infectivity of enveloped viruses, including Newcastle disease virus [92] Measles virus [93], and HIV-1 [94]. Similar observations have been made with arenaviruses. Removal of the entire LCMV GP2 cytosolic tail as well as partial deletion of the three C-terminal amino acids RRK prevent maturation of GPC without interfering with its normal transport to the cell surface [65]. As similar role of amino acid residues in the cytoplasmic domain for GPC cleavage was observed by Schlie et al. in the context of LASV GPC [95]. In arenaviruses, lack of cleavage has thus a drastic impact on infectious particles production since the process of GP incorporation into nascent virions discriminates processed over unprocessed GPC.

3. Role of the envelope glycoprotein on virus assembly and particle formation

Viral infection induces a global reprogramming of cellular processes, including alterations the organization of intracellular membranes and organelles [105,106]. Assembly of the viral components, and in particular GP, to form progeny infectious particle is still a process that remains for many aspects unknown. As introduced above, the driving force for arenaviruses budding is the matrix protein Z [34,35] which interacts via its late or RING domain with Tsg101, a member of the ESCRT machinery [34,36]. Myristoylation of Z is crucial for the correct matrix protein localization and therefore budding [107]. Z possesses per se budding properties and does not require any other viral protein to accomplish its function. However, the ability to produce infectious particles resides on the assembly of the four different viral proteins in a synchronized fashion. Thus, Z is required to interact with the SSP/GP1/GP2 complex that decorates the surface of the nascent particle. Confocal and biochemical analyses showed a direct LCMV and LASV GP1/GP2-Z interaction, dependent on the stable signal peptide of the GP complex [37]. Cells that express LASV GPC together with Z show a partial co-localization in vesicle-like structures near the nucleus [108]. Sub-cellular localization of the envelope glycoprotein is not modified by the presence of Z [34]. Z myristoylation, but not on the Z late (L) or RING domain was shown to be responsible for the matrix protein binding to the envelope GP in OW arenaviruses [37]. However, disrupting the Z RING domain resulted in a drastic loss of TCRV and JUNV GP incorporation, suggesting some differences in the detailed molecular interactions underlying virion assembly in OW and NW viruses [109]. Further analyses are required to better understand the role of the GP complex in the virus budding events. The mechanisms underlying the selective incorporation of cleaved over uncleaved envelope GPs remain unclear and may involve different tertiary/quaternary structures of the mature SSP/GP1/GP2 complex in comparison to immature GPC [20]. Inhibition of virus assembly and budding is becoming more and more attractive as a drug target, opening the possibility to block egress of progeny virions from already infected cells. A detailed analysis of the molecular interactions underlying the recruitment of processed GP, Z, and the RNP into budding zones in infected cells will likely reveal promising drug targets for novel therapeutics to combat human arenavirus infection.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant FN 31003A-135536 (S.K.) and funds from the University of Lausanne.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Armstrong, C.; Lillie, R. Experimental lymphocytic choriomeningitis of monkeys and mice produced by a virus encountered in studies of the 1933 St. Luis encephalitis epidemic. Publ Health Rep 1934, 49, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, T.M.; McNair Scott, T.F. Meningitis in Man Caused by a Filterable Virus. Science 1935, 81, 439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Traub, E. A Filterable Virus Recovered from White Mice. Science 1935, 81, (2099), 298–299. [Google Scholar]

- Charrel, R.N.; Coutard, B.; Baronti, C.; Canard, B.; Nougairede, A.; Frangeul, A.; Morin, B.; Jamal, S.; Schmidt, C.L.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Klempa, B.; de Lamballerie, X. Arenaviruses and hantaviruses: from epidemiology and genomics to antivirals. Antiviral research 2011, 90, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisbert, T.W.; Jahrling, P.B. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nature medicine 2004, 10, S110–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J.B.; King, I.J.; Webb, P.A.; Johnson, K.M.; O'Sullivan, R.; Smith, E.S.; Trippel, S.; Tong, T.C. A case-control study of the clinical diagnosis and course of Lassa fever. The Journal of infectious diseases 1987, 155, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.J. Human infection with arenaviruses in the Americas. Current topics in microbiology and immunology 2002, 262, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiztegui, J.I. Clinical and epidemiological patterns of Argentine haemorrhagic fever. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1975, 52, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Parodi, A.S.; Greenway, D.J.; Rugiero, H.R.; Frigerio, M.; De La Barrera, J.M.; Mettler, N.; Garzon, F.; Boxaca, M.; Guerrero, L.; Nota, N. [Concerning the epidemic outbreak in Junin]. El Dia medico 1958, 30, 2300–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Weissenbacher, M.C.; Laguens, R.P.; Coto, C.E. Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Current topics in microbiology and immunology 1987, 134, 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Razonable, R.R. Rare, unusual, and less common virus infections after organ transplantation. Current opinion in organ transplantation 2011, 16, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthius, D.J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: a prenatal and postnatal threat. Advances in pediatrics 2009, 56, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahy, B.W.; Dykewicz, C.; Fisher-Hoch, S.; Ostroff, S.; Tipple, M.; Sanchez, A. Virus zoonoses and their potential for contamination of cell cultures. Developments in biological standardization 1991, 75, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, S.; Erickson, B.R.; Agudo, R.; Blair, P.J.; Vallejo, E.; Albarino, C.G.; Vargas, J.; Comer, J.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Olson, J.G.; Nichol, S.T. Chapare virus, a newly discovered arenavirus isolated from a fatal hemorrhagic fever case in Bolivia. PLoS pathogens 2008, 4, e1000047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briese, T.; Paweska, J.T.; McMullan, L.K.; Hutchison, S.K.; Street, C.; Palacios, G.; Khristova, M.L.; Weyer, J.; Swanepoel, R.; Egholm, M.; Nichol, S.T.; Lipkin, W.I. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever-associated arenavirus from southern Africa. PLoS pathogens 2009, 5, e1000455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, K.S.; Arthur, R.R.; O'Connor, R.; Fernandez, J. Assessment of public health events through International Health Regulations, United States, 2007-2011. Emerging infectious diseases 2012, 18, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, J.C. Molecular and cell biology of the prototypic arenavirus LCMV: implications for understanding and combating hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2009, 1171 Suppl 1, E57–E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmeier, M.J.; de la Torre, J.C.; Peters, C.J. Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology, 4th; Knipe D., L., Howley P., M., Eds.; Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, 2007; pp. 1791–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Emonet, S.F.; de la Torre, J.C.; Domingo, E.; Sevilla, N. Arenavirus genetic diversity and its biological implications. In Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases; 2009; Volume 9, pp. 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Schlie, K.; Maisa, A.; Lennartz, F.; Stroher, U.; Garten, W.; Strecker, T. Characterization of Lassa virus glycoprotein oligomerization and influence of cholesterol on virus replication. Journal of virology 2010, 84, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, B.; Knipe, D.M.; Howley, P.M. Fields Virology, 5th ed; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Henry, M.D.; Borrow, P.; Yamada, H.; Elder, J.H.; Ravkov, E.V.; Nichol, S.T.; Compans, R.W.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B. Identification of alpha-dystroglycan as a receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and Lassa fever virus. Science 1998, 282, (5396), 2079–2081. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, S.; Borrow, P.; Oldstone, M.B. Receptor structure, binding, and cell entry of arenavirus. Current topics in microbiology and immunology 2002, 262, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoshitzky, S.R.; Abraham, J.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Kuhn, J.H.; Nguyen, D.; Li, W.; Nagel, J.; Schmidt, P.J.; Nunberg, J.H.; Andrews, N.C.; Farzan, M.; Choe, H. Transferrin receptor 1 is a cellular receptor for New World haemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Nature 2007, 446, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoshitzky, S.R.; Kuhn, J.H.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Albarino, C.G.; Nguyen, D.P.; Salazar-Bravo, J.; Dorfman, T.; Lee, A.S.; Wang, E.; Ross, S.R.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. Receptor determinants of zoonotic transmission of New World hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, (7), 2664–2669. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqual, G.; Rojek, J.M.; Masin, M.; Chatton, J.Y.; Kunz, S. Old world arenaviruses enter the host cell via the multivesicular body and depend on the endosomal sorting complex required for transport. PLoS pathogens 2011, 7, e1002232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pythoud, C.; Rodrigo, W.W.; Pasqual, G.; Rothenberger, S.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S. Arenavirus nucleoprotein targets interferon regulatory factor-activating kinase IKKepsilon. Journal of virology 2012, 86, 7728–7738. [Google Scholar]

- Aisen, P. Transferrin receptor 1. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2004, 36, 2137–2143. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Kolokoltsova, O.A.; Yun, N.E.; Seregin, A.V.; Poussard, A.L.; Walker, A.G.; Brasier, A.R.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, B.; de la Torre, J.C.; Paessler, S. Junin virus infection activates the type I interferon pathway in a RIG-I-dependent manner. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2012, 6, e1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqual, G.; Rojek, J.M.; Masin, M.; Chatton, J.Y.; Kunz, S. Old world arenaviruses enter the host cell via the multivesicular body and depend on the endosomal sorting complex required for transport. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, (9), e1002232. [Google Scholar]

- Iapalucci, S.; Lopez, N.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. The 3' end termini of the Tacaribe arenavirus subgenomic RNAs. Virology 1991, 182, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; de la Torre, J.C. Characterization of the genomic promoter of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Journal of virology 2003, 77, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, N.L.; York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Arenavirus infection induces discrete cytosolic structures for RNA replication. Journal of virology 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, M.; Craven, R.C.; de la Torre, J.C. The small RING finger protein Z drives arenavirus budding: implications for antiviral strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, (22), 12978–12983. [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, T.; Eichler, R.; Meulen, J.; Weissenhorn, W.; Dieter Klenk, H.; Garten, W.; Lenz, O. Lassa virus Z protein is a matrix protein and sufficient for the release of virus-like particles [corrected]. Journal of virology 2003, 77, 10700–10705. [Google Scholar]

- Urata, S.; Noda, T.; Kawaoka, Y.; Yokosawa, H.; Yasuda, J. Cellular factors required for Lassa virus budding. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 4191–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capul, A.A.; Perez, M.; Burke, E.; Kunz, S.; Buchmeier, M.J.; de la Torre, J.C. Arenavirus Z-glycoprotein association requires Z myristoylation but not functional RING or late domains. J Virol 2007, 81, (17), 9451–9460. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihothram, S.S.; York, J.; Trahey, M.; Nunberg, J.H. Bitopic membrane topology of the stable signal peptide in the tripartite Junin virus GP-C envelope glycoprotein complex. Journal of virology 2007, 81, 4331–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, W.R.; Popplau, D.; Garten, W.; von Laer, D.; Lenz, O. Endoproteolytic processing of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein by the subtilase SKI-1/S1P. Journal of virology 2003, 77, 2866–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, O.; ter Meulen, J.; Klenk, H.D.; Seidah, N.G.; Garten, W. The Lassa virus glycoprotein precursor GP-C is proteolytically processed by subtilase SKI-1/S1P. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2001; 98, pp. 12701–12705. [Google Scholar]

- Rojek, J.M.; Lee, A.M.; Nguyen, N.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Kunz, S. Site 1 protease is required for proteolytic processing of the glycoproteins of the South American hemorrhagic fever viruses Junin, Machupo, and Guanarito. Journal of virology 2008, 82, 6045–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.; Romanowski, V.; Lu, M.; Nunberg, J.H. The signal peptide of the Junin arenavirus envelope glycoprotein is myristoylated and forms an essential subunit of the mature G1-G2 complex. Journal of virology 2004, 78, 10783–10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, R.; Lenz, O.; Garten, W.; Strecker, T. The role of single N-glycans in proteolytic processing and cell surface transport of the Lassa virus glycoprotein GP-C. Virology journal 2006, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunberg, J.H.; York, J. The curious case of arenavirus entry, and its inhibition. Viruses 2012, 4, (1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froeschke, M.; Basler, M.; Groettrup, M.; Dobberstein, B. Long-lived signal peptide of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein pGP-C. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, (43), 41914–41920. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, R.; Lenz, O.; Strecker, T.; Garten, W. Signal peptide of Lassa virus glycoprotein GP-C exhibits an unusual length. FEBS Lett 2003, 538, (1-3), 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.; Romanowski, V.; Lu, M.; Nunberg, J.H. The signal peptide of the Junin arenavirus envelope glycoprotein is myristoylated and forms an essential subunit of the mature G1-G2 complex. J Virol. 2004, 78, (19), 10783–10792. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Role of the stable signal peptide of Junin arenavirus envelope glycoprotein in pH-dependent membrane fusion. J Virol 2006, 80, (15), 7775–7780. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Intersubunit interactions modulate pH-induced activation of membrane fusion by the Junin virus envelope glycoprotein GPC. J Virol 2009, 83, (9), 4121–4126. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, R.; Lenz, O.; Strecker, T.; Eickmann, M.; Klenk, H.D.; Garten, W. Identification of Lassa virus glycoprotein signal peptide as a trans-acting maturation factor. EMBO reports 2003, 4, (11), 1084–1088. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Distinct requirements for signal peptidase processing and function in the stable signal peptide subunit of the Junin virus envelope glycoprotein. Virology 2007, 359, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarino, C.G.; Bird, B.H.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Dodd, K.A.; White, D.M.; Bergeron, E.; Shrivastava-Ranjan, P.; Nichol, S.T. Reverse genetics generation of chimeric infectious Junin/Lassa virus is dependent on interaction of homologous glycoprotein stable signal peptide and G2 cytoplasmic domains. Journal of virology 2011, 85, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihothram, S.S.; York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Role of the stable signal peptide and cytoplasmic domain of G2 in regulating intracellular transport of the Junin virus envelope glycoprotein complex. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 5189–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.; Dai, D.; Amberg, S.M.; Nunberg, J.H. pH-induced activation of arenavirus membrane fusion is antagonized by small-molecule inhibitors. Journal of virology 2008, 82, 10932–10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, E.L.; York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Dissection of the role of the stable signal peptide of the arenavirus envelope glycoprotein in membrane fusion. Journal of virology 2012, 86, 6138–6145. [Google Scholar]

- Braakman, I.; van Anken, E. Folding of viral envelope glycoproteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Traffic 2000, 1, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, C.J.; Capul, A.A.; Lauron, E.J.; Bederka, L.H.; Knopp, K.A.; Buchmeier, M.J. Glycosylation modulates arenavirus glycoprotein expression and function. Virology 2011, 409, (2), 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kido, H.; Okumura, Y.; Takahashi, E.; Pan, H.Y.; Wang, S.; Chida, J.; Le, T.Q.; Yano, M. Host envelope glycoprotein processing proteases are indispensable for entry into human cells by seasonal and highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Journal of molecular and genetic medicine : an international journal of biomedical research 2008, 3, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Hallenberger, S.; Bosch, V.; Angliker, H.; Shaw, E.; Klenk, H.D.; Garten, W. Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gp160. Nature 1992, 360, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, H.; Okumura, Y.; Yamada, H.; Mizuno, D.; Higashi, Y.; Yano, M. Secretory leukoprotease inhibitor and pulmonary surfactant serve as principal defenses against influenza A virus infection in the airway and chemical agents up-regulating their levels may have therapeutic potential. Biological chemistry 2004, 385, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, W.S.; Cao, J.; Jackson, L.; Jimenez, J.; Peng, Q.; Wu, H.; Isaacson, J.; Butler, S.L.; Chu, A.; Graham, J.; Malfait, A.M.; Tortorella, M.; Patick, A.K. Identification and characterization of UK-201844, a novel inhibitor that interferes with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 processing. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2007, 51, 3554–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Hirano, A.; Stenglein, S.; Nelson, J.; Thomas, G.; Wong, T.C. Engineered serine protease inhibitor prevents furin-catalyzed activation of the fusion glycoprotein and production of infectious measles virus. Journal of virology 1995, 69, 3206–3210. [Google Scholar]

- Ozden, S.; Lucas-Hourani, M.; Ceccaldi, P.E.; Basak, A.; Valentine, M.; Benjannet, S.; Hamelin, J.; Jacob, Y.; Mamchaoui, K.; Mouly, V.; Despres, P.; Gessain, A.; Butler-Browne, G.; Chretien, M.; Tangy, F.; Vidalain, P.O.; Seidah, N.G. Inhibition of Chikungunya virus infection in cultured human muscle cells by furin inhibitors: impairment of the maturation of the E2 surface glycoprotein. The Journal of biological chemistry 2008, 283, 21899–21908. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.M.; Delos, S.E.; Brecher, M.; Schornberg, K. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology 2008, 43, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, S.; Edelmann, K.H.; de la Torre, J.C.; Gorney, R.; Oldstone, M.B. Mechanisms for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein cleavage, transport, and incorporation into virions. Virology 2003, 314, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, E.B.; Mersich, S.E.; Candurra, N.A. Intracellular processing and transport of Junin virus glycoproteins influences virion infectivity. Virus research 1994, 34, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquato, A.; Burri, D.J.; Traba, E.G.; Hanna-El-Daher, L.; Seidah, N.G.; Kunz, S. Arenavirus envelope glycoproteins mimic autoprocessing sites of the cellular proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin isozyme-1/site-1 protease. Virology 2011, 417, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschli, B.; Quirin, K.; Wepf, A.; Weber, J.; Zinkernagel, R.; Hengartner, H. Identification of an N-terminal trimeric coiled-coil core within arenavirus glycoprotein 2 permits assignment to class I viral fusion proteins. J Virol. 2006, 80, (12), 5897–5907. [Google Scholar]

- Igonet, S.; Vaney, M.C.; Vonhrein, C.; Bricogne, G.; Stura, E.A.; Hengartner, H.; Eschli, B.; Rey, F.A. X-ray structure of the arenavirus glycoprotein GP2 in its postfusion hairpin conformation. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2011; 108, pp. 19967–19972. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquato, A.; Pullikotil, P.; Asselin, M.C.; Vacatello, M.; Paolillo, L.; Ghezzo, F.; Basso, F.; Di Bello, C.; Dettin, M.; Seidah, N.G. The proprotein convertase SKI-1/S1P. In vitro analysis of Lassa virus glycoprotein-derived substrates and ex vivo validation of irreversible peptide inhibitors. The Journal of biological chemistry 2006, 281, 23471–23481. [Google Scholar]

- Elagoz, A.; Benjannet, S.; Mammarbassi, A.; Wickham, L.; Seidah, N.G. Biosynthesis and cellular trafficking of the convertase SKI-1/S1P: ectodomain shedding requires SKI-1 activity. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 11265–11275. [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade, P.J.; Cheng, D.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. Autocatalytic processing of site-1 protease removes propeptide and permits cleavage of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry 1999, 274, 22795–22804. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, J.; Rawson, R.B.; Espenshade, P.J.; Cheng, D.; Seegmiller, A.C.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. Molecular identification of the sterol-regulated luminal protease that cleaves SREBPs and controls lipid composition of animal cells. Molecular cells 1998, 2, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Robbins, M.D.; Warren, L.C.; Xia, D.; Petras, S.F.; Valentine, J.J.; Varghese, A.H.; Wang, I.K.; Subashi, T.A.; Shelly, L.D.; Hay, B.A.; Landschulz, K.T.; Geoghegan, K.F.; Harwood, H.J., Jr. Pharmacologic inhibition of site 1 protease activity inhibits sterol regulatory element-binding protein processing and reduces lipogenic enzyme gene expression and lipid synthesis in cultured cells and experimental animals. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2008, 326, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Rawson, R.B.; Komuro, R.; Chen, X.; Dave, U.P.; Prywes, R.; Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Molecular cell 2000, 6, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2008, 65, 862–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, K.; Kollmann, K.; Schweizer, M.; Braulke, T.; Pohl, S. A key enzyme in the biogenesis of lysosomes is a protease that regulates cholesterol metabolism. Science 2011, 333, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Seidah, N.G.; Mowla, S.J.; Hamelin, J.; Mamarbachi, A.M.; Benjannet, S.; Toure, B.B.; Basak, A.; Munzer, J.S.; Marcinkiewicz, J.; Zhong, M.; Barale, J.C.; Lazure, C.; Murphy, R.A.; Chretien, M.; Marcinkiewicz, M. Mammalian subtilisin/kexin isozyme SKI-1: A widely expressed proprotein convertase with a unique cleavage specificity and cellular localization. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 1999; 96, pp. 1321–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Tassew, N.G.; Charish, J.; Seidah, N.G.; Monnier, P.P. SKI-1 and Furin generate multiple RGMa fragments that regulate axonal growth. Developmental cell 2012, 22, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, J.P.; Huffman, N.T.; Cui, C.; Henderson, E.P.; Midura, R.J.; Seidah, N.G. Potential role of proprotein convertase SKI-1 in the mineralization of primary bone. Cells, tissues, organs 2009, 189, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlombs, K.; Wagner, T.; Scheel, J. Site-1 protease is required for cartilage development in zebrafish. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2003; 100, pp. 14024–14029. [Google Scholar]

- Rutschmann, S.; Crozat, K.; Li, X.; Du, X.; Hanselman, J.C.; Shigeoka, A.A.; Brandl, K.; Popkin, D.L.; McKay, D.B.; Xia, Y.; Moresco, E.M.; Beutler, B. Hypopigmentation and maternal-zygotic embryonic lethality caused by a hypomorphic mbtps1 mutation in mice. G3 2012, 2, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Pinson, K.I.; Kelly, O.G.; Brennan, J.; Zupicich, J.; Scherz, P.; Leighton, P.A.; Goodrich, L.V.; Lu, X.; Avery, B.J.; Tate, P.; Dill, K.; Pangilinan, E.; Wakenight, P.; Tessier-Lavigne, M.; Skarnes, W.C. Functional analysis of secreted and transmembrane proteins critical to mouse development. Nature genetics 2001, 28, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, K.; Rutschmann, S.; Li, X.; Du, X.; Xiao, N.; Schnabl, B.; Brenner, D.A.; Beutler, B. Enhanced sensitivity to DSS colitis caused by a hypomorphic Mbtps1 mutation disrupting the ATF6-driven unfolded protein response. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2009; 106, pp. 3300–3305. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, D.L.; Teijaro, J.R.; Sullivan, B.M.; Urata, S.; Rutschmann, S.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S.; Beutler, B.; Oldstone, M. Hypomorphic mutation in the site-1 protease Mbtps1 endows resistance to persistent viral infection in a cell-specific manner. Cell host & microbe 2011, 9, (3), 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Burri, D.J.; Pasqual, G.; Rochat, C.; Seidah, N.G.; Pasquato, A.; Kunz, S. Molecular characterization of the processing of arenavirus envelope glycoprotein precursors by subtilisin kexin isozyme-1/site-1 protease. Journal of virology 2012, 86, 4935–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candurra, N.A.; Damonte, E.B. Effect of inhibitors of the intracellular exocytic pathway on glycoprotein processing and maturation of Junin virus. Archives of virology 1997, 142, 2179–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldstone, M.B.; Buchmeier, M.J. Restricted expression of viral glycoprotein in cells of persistently infected mice. Nature. 1982, 300, (5890), 360–362. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqual, G.; Burri, D.J.; Pasquato, A.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S. Role of the host cell's unfolded protein response in arenavirus infection. Journal of virology 2011, 85, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, A.; Chretien, M.; Seidah, N.G. A rapid fluorometric assay for the proteolytic activity of SKI-1/S1P based on the surface glycoprotein of the hemorrhagic fever Lassa virus. FEBS letters 2002, 514, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, C.; Klenk, H.D.; ter Meulen, J. Amino acids from both N-terminal hydrophobic regions of the Lassa virus envelope glycoprotein GP-2 are critical for pH-dependent membrane fusion and infectivity. The Journal of general virology 2007, 88, 2320–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergel, T.; Morrison, T.G. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the fusion glycoprotein of Newcastle disease virus depress syncytia formation. Virology 1995, 210, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathomen, T.; Naim, H.Y.; Cattaneo, R. Measles viruses with altered envelope protein cytoplasmic tails gain cell fusion competence. Journal of virology 1998, 72, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Gabuzda, D.H.; Lever, A.; Terwilliger, E.; Sodroski, J. Effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain on biological functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. Journal of virology 1992, 66, 3306–3315. [Google Scholar]

- Schlie, K.; Strecker, T.; Garten, W. Maturation cleavage within the ectodomain of Lassa virus glycoprotein relies on stabilization by the cytoplasmic tail. FEBS letters 2010, 584, 4379–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohottalage, D.; Goto, N.; Basak, A. Subtilisin kexin isozyme-1 (SKI-1): production, purification, inhibitor design and biochemical applications. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2009, 611, 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rojek, J.M.; Pasqual, G.; Sanchez, A.B.; Nguyen, N.T.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S. Targeting the proteolytic processing of the viral glycoprotein precursor is a promising novel antiviral strategy against arenaviruses. Journal of virology 2010, 84, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisa, A.; Stroher, U.; Klenk, H.D.; Garten, W.; Strecker, T. Inhibition of Lassa virus glycoprotein cleavage and multicycle replication by site 1 protease-adapted alpha(1)-antitrypsin variants. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2009, 3, e446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquato, A.; Rochat, C.; Burri, D.J.; Pasqual, G.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S. Evaluation of the anti-arenaviral activity of the subtilisin kexin isozyme-1/site-1 protease inhibitor PF-429242. Virology 2012, 423, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, B.A.; Abrams, B.; Zumbrunn, A.Y.; Valentine, J.J.; Warren, L.C.; Petras, S.F.; Shelly, L.D.; Xia, A.; Varghese, A.H.; Hawkins, J.L.; Van Camp, J.A.; Robbins, M.D.; Landschulz, K.; Harwood, H.J., Jr. Aminopyrrolidineamide inhibitors of site-1 protease. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2007, 17, 4411–4414. [Google Scholar]

- Urata, S.; Yun, N.; Pasquato, A.; Paessler, S.; Kunz, S.; de la Torre, J.C. Antiviral activity of a small-molecule inhibitor of arenavirus glycoprotein processing by the cellular site 1 protease. Journal of virology 2011, 85, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldstone, M.B.; Buchmeier, M.J. Restricted expression of viral glycoprotein in cells of persistently infected mice. Nature 1982, 300, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullikotil, P.; Benjannet, S.; Mayne, J.; Seidah, N.G. The proprotein convertase SKI-1/S1P: alternate translation and subcellular localization. The Journal of biological chemistry 2007, 282, 27402–27413. [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead, A.D.; Knecht, W.; Lazarov, I.; Dixit, S.B.; Jean, F. Human subtilase SKI-1/S1P is a master regulator of the HCV Lifecycle and a potential host cell target for developing indirect-acting antiviral agents. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, (1), e1002468. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, N.Y.; Ilnytska, O.; Belov, G.; Santiana, M.; Chen, Y.H.; Takvorian, P.M.; Pau, C.; van der Schaar, H.; Kaushik-Basu, N.; Balla, T.; Cameron, C.E.; Ehrenfeld, E.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.; Altan-Bonnet, N. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell 2010, 141, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.; Riley, C.; Isaac, G.; Hopf-Jannasch, A.S.; Moore, R.J.; Weitz, K.W.; Pasa-Tolic, L.; Metz, T.O.; Adamec, J.; Kuhn, R.J. Dengue virus infection perturbs lipid homeostasis in infected mosquito cells. PLoS pathogens 2012, 8, e1002584. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, M.; Greenwald, D.L.; de la Torre, J.C. Myristoylation of the RING finger Z protein is essential for arenavirus budding. J Virol 2004, 78, (20), 11443–11448. [Google Scholar]

- Schlie, K.; Maisa, A.; Freiberg, F.; Groseth, A.; Strecker, T.; Garten, W. Viral protein determinants of Lassa virus entry and release from polarized epithelial cells. Journal of virology 2010, 84, 3178–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabona, J.C.; Levingston Macleod, J.M.; Loureiro, M.E.; Gomez, G.A.; Lopez, N. The RING domain and the L79 residue of Z protein are involved in both the rescue of nucleocapsids and the incorporation of glycoproteins into infectious chimeric arenavirus-like particles. Journal of virology 2009, 83, 7029–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).