Contextual Exploration of a New Family Caregiver Support Concept for Geriatric Settings Using a Participatory Health Research Strategy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Strategy

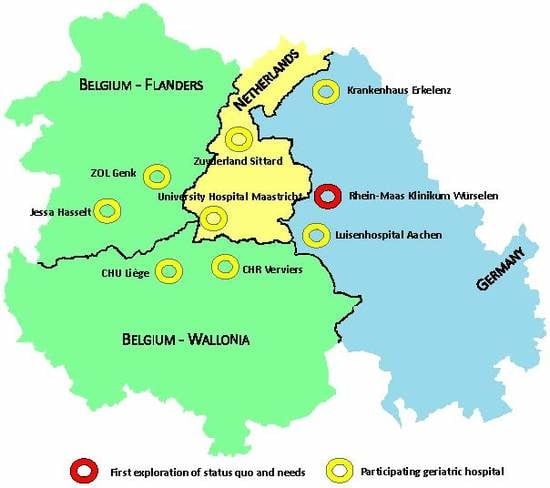

2.2. Setting and Research Team

2.3. Project Realization and Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Orientation—March 2017

3.2. Phase 2: Setting Up—April 2017

- (1)

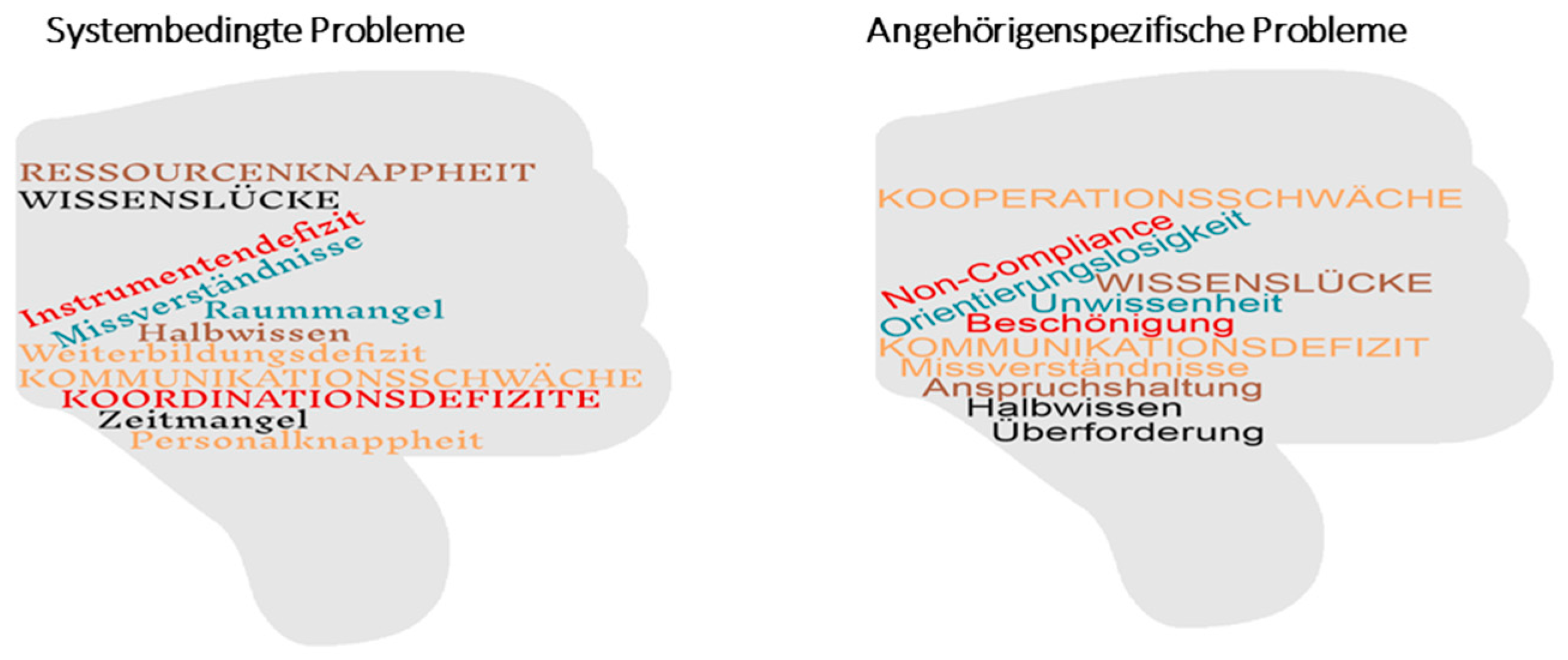

- Problem definition. Using the brainstorming method, all team members reflected upon their daily challenges in providing caregiver support. This interactive process resulted in formulating the problem statement. System-related problems, such as knowledge gaps, lack of resources, coordination deficits, as well as caregiver-related problems, such as non-compliance, overburdening, and communication deficits, were identified. Important individual contributions from members of the research team concerning potential problems were combined in a word cloud and presented as an overview to the research team (Figure 3).

- (2)

- Expectations. The expectations concerning the new job description of the Geriatric Family Companion were explored by the professionals as a group as well as for each individual team member personally, and for the caregiver–patient dyad as perceived by the care professionals. Discussions took place in small groups of 3–4 professionals (“Murmelgruppen”) after which the results were presented to the entire research team. The team then structured and prioritized the findings. Individual care professionals expect to: have more time personally to support caregivers individually according to their different needs when support is scheduled in the normal working hours and not in extra time, benefit from task simplification, make personal improvements and get appreciation. For their own profession, they also expect improved time allocation, a better infrastructure, and improved competence. The project might help to give caregivers and patients more consultation time, individualized and improved support, as well as more satisfaction with the services.

- (3)

- Research question. As most participants indicated they were inexperienced in formulating a research question, they asked for moderation by the external researchers. Triggering questions such as: Who is the focus of interest? What do we want to know? Where does the study take place? helped the research team in formulating the research question: “How does the multidisciplinary research team of the Rhein-Maas Klinikum currently support family caregivers, and what is needed to provide tailored support to caregivers?”

3.3. Phase 3: Planning—May/June 2017

3.4. Phase 4: Data Collection—June/September 2017

3.5. Phase 5: Data Analyses and Conclusion—October/November 2017

3.6. Phase 6: Reporting—December 2017

4. Discussion

Considerations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Status-Quo Assessment (“How Do You Experience the Current Support?”) | Categories | Needs Assessment (“What Would Be Needed?”) |

|---|---|---|

| How do you experience the current family caregiver support in your department? On which occasions do you have contact with family caregivers? Can you recall a meeting with family caregivers? | Warming up | What do you need in general to provide family caregiver support? Which specific support offers would be helpful or applicable in your department? |

| What burdens family caregivers of geriatric patients? How do you currently meet the family caregivers’ needs? In what situations or circumstances require family caregivers your support? | Caregiver needs | In what situation and circumstances would family caregivers need support? |

| What type of information do you already have about the family caregivers? Which caregiver-specific information is systematically recorded? | Information about the caregiver | Which information should be systematically recorded in order to enable personalized caregiver support? Would it be helpful if family caregivers will list their needs in a self-registered assessment? Please justify your decision. |

| What expertise of your own do you use when supporting family caregivers? What expertise and knowledge do you lack? In which caregiver-specific capacity building activities did you participate? Which caregiver-specific capacity building activities are made available for you by your employer? | Expertise (e.g., for example about financing, housing adaptation, clinical picture) | What kind of knowledge would be necessary to advise family caregivers of geriatric patients? What aspects of family caregiver support should be incorporated in education or academic studies? Which further capacity building offers do you require? |

| Do you feel prepared for dealing with family caregiver issues? What skills do you use in your daily work with family caregivers of geriatric patients? Which skills do you miss? How do you handle "difficult" family caregivers? | Skills (e.g., dealing with anger, grief, lack of compliance, or conflicts) | What skills should you require for family caregiver support? What skills would you like to develop further? What should your employer do to improve your caregiver support skills? |

| Which resources (infrastructure, time and material) are available for you to provide personalized family caregivers support? Who is in general responsible for providing caregiver support? Why? | Resources (e.g., consultation room, time, counselling material) | Which resources do you require to provide personalized family caregivers support? Would an assessment instrument for family caregivers make sense? Please explain! What advantages would a focus-person system for family caregivers imply for: (a) family caregivers, (b) patients, (c) geriatric support team, and (d) support system in the home care environment? |

| How would you define your role in the current family caregiver support process? Are there designated office hours available for family caregiver support? | Management (“How do you engage with your family caregivers?”) | What should be your role in family caregiver support in the future? How should caregiver support offers be managed in your department? |

| To which extent is supporting family caregivers outlined in your job description, or do you feel ‘morally’ committed? How would you estimate the level of importance of family caregiver support in the eyes of your boss? | Mandate | What should your hospital management do to enable and maintain personalized family caregiver support? How could your daily support efforts be more appreciated by the management? |

| Which specific family caregiver support offers exist, or existed, within your setting and are/were these offers accredited? Which external offers (e.g., from the communal services) do you know? And which do you recommend, and when? Where do you spot weaknesses in the current caregiver support? | Family caregiver support offers (“What are important ingredients for a personalized caregiver support?”) | What should the ideal support offer for family caregivers in your department look like? Please reflect on the following items:

|

References

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 283: Health and Long Term Care in the European Union; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/surveyKy/657/p/4 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver Assessment: Principles, Guidelines, and Strategies for Change. In National Consensus Development Conference; Family Caregiver Alliance: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; Available online: https://caregiver.org/sites/caregiver.org/files/pdfs/v1_consensus.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2016).

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Pflegestatistik 2013. In Pflege im Rahmen der Pflegeversicherung. Deutschlandergebnisse; DESTATIS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Pflege/PflegeDeutschlandergebnisse5224001139004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Willemé, P. The Long-Term Care System for the Elderly in Belgium. In ENEPRI Research Report No. 70; Assessing Needs of Care in European Nations (ANCIEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2010; Available online: http://www.ancien-longtermcare.eu/node/27 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Putman, L.; Verbeek-Oudijk, D.; De Klerk, M.; Eggink, E. Zorg en Ondersteuning in Nederland: Kerncijfers 2014; The Netherlands Institute for Social Research|SCP: Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, R.; Tmanova, L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver Burden. A Clinical Review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broese van Groenou, M.; De Boer, A.; Iedema, J. Positive and negative evaluation of caregiving among three different types of informal care relationships. Eur. J. Ageing 2013, 10, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garlo, K.; O’Leary, J.R.; Van Ness, P.H.; Fried, T.R. Burden in caregivers of older adults with advanced illness. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 2315–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummer, K.; Budnick, A.; Blüher, S.; Dräger, D. Gesundheitsförderung für ältere pflegende Angehörige. Ressourcen und Risiken—Bedarfslagen und Angebotsstrukturen. Präv. Gesundh. 2010, 5, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 62B, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, A.; Wilz, G. Die Belastungen pflegender Angehöriger bei Demenz. Entstehungsbedingungen und Interventionsmöglichkeiten. Nervenarzt 2011, 82, 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, J.A.; Loscalzo, M.; Zabora, J.; Houts, P.S.; Hooker, C.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K. Problem-Solving Cancer Care Education for Patients and Caregivers. Cancer Pract. 2001, 9, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherbring, M. Effect of caregiver perception of preparedness on burden in an oncology population. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2002, 29, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, K.L.; Stewart, B.J.; Archbold, P.G.; Dodd, M.J.; Dibble, S.J. Family caregiving skill: Development of the concept. Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedström, E.; Skovdahl, K.; Isaksson, A.; Windah, J.; Kihlgren, A. Understanding the next of kin’s experience of their life situation in informal caregiving of older persons. Clin. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 2, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringer, T.; Hazzan, A.A.; Agarwal, A.; Mutsaers, A.; Papaioannou, A. Relationship between family caregiver burden and physical frailty in older adults without dementia: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannetti, E.R.; Wolff, J.L.; Xue, Q.; Weiss, C.O.; Leff, B.; Boult, C.; Hughes, T.; Boyd, C.M. Difficulty Assisting with Health Care Tasks among Caregivers of Multimorbid Older Adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meranius, M.S.; Josefsson, K. Health and social care management for older adults with multimorbidity: A multiperspective approach. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, B.; Young, M.; Cox, K.; Martz, K.; Creasy, C. The Crisis of Stroke: Experiences of Patients and Their Family Caregivers. Top. Stroke Rehab. 2011, 18, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.L.; Teixeira, H.J.; Teixeira, M.J.C.; Freitas, S. The needs of informal caregivers of elderly people living at home: An integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corry, M.; While, A.; Neenan, K.; Smith, V. A systematic review of systematic reviews on interventions for caregivers of people with chronic conditions. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 718–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, J.I.; Gignac, M.A.M. Timing It Right: A conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the hospital to the home. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 70, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetzstein, M.; Rommel, A.; Lange, C. Pflegende Angehörige—Deutschlands größter Pflegedienst. In Gesundheitsberichterstattung Kompakt; Robert Koch Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hartmann, M.; Wens, J.; Verhoeven, V.; Remmen, R. The effect of caregiver support interventions for informal caregivers of community-dwelling frail elderly: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbauer, J.; Floren, M.; Krieger, T. Der Angehörigenlotse: Erprobung und Evaluation eines phasenübergreifenden Beratungskonzepts für Angehörige von Schlaganfallbetroffenen. Praxis Klin. Verhalt. Rehabil. 2016, 99, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, T.; Feron, F.; Boumans, N.; Dorant, E. Developing implementation management instruments in a complex intervention for stroke caregivers based on combined stakeholder and risk analyses. (Under review).

- Krieger, T.; Feron, F.; Floren, M.; Dorant, E. Optimizing the concept for a complex stroke caregiver support programme using participatory health research. (Under review).

- Bircher, J.; Kuruvilla, S. Defining health by addressing individual, social, and environmental determinants: New opportunities for health care and public health. J. Public Health Policy 2014, 35, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Project Management Institute—PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th ed.; PMI: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, M.; De Leon, N.; George, G.; Thompson, P. Managing by design. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Brito, I.; Cook, T.; Harris, J.; Kleba, M.; Madsen, W.; Springett, J.; Wakeford, T. What Is Participatory Health Research? Position Paper No. 1; International Collaboration for participatory Health Research: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Available online: http://www.icphr.org/uploads/2/0/3/9/20399575/ichpr_position_paper_1_defintion_-_version_may_2013.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Green, L.W.; George, A.; Daniel, M.; Frankish, C.J.; Herbert, C.P.; Bowie, W.R.; O’Neill, M. Study of Participatory Research in Health Promotion; Royal Society of Canada: Ottawa, QC, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M. Was ist Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung? Positionspapier der International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research. Präv. Gesundh. 2013, 3, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargo, M.; Mercer, S. The Value and Challenges of Participatory Research: Strengthening Its Practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2008, 29, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwall, A. Towards participatory practice: Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) and the participatory process. In Participatory Research in Health: Issues and Experiences; De Koning, K., Martin, M., Eds.; Vistaar Publications: New Delhi, India, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, T.; Corneil, W.; Kuziemsky, C.; Toal-Sullivan, D. Use of the Structured Interview Matrix to Enhance Community Resilience Through Collaboration and Inclusive Engagement. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2014, 32, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonte, R.; Feather, J.; Hills, M. A story/dialogue for health promotion knowledge development and evaluation. Health Ed. Res. 1999, 14, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsden, J.; Van Wynsberghe, R. Community mapping as a research tool with youth. Action Res. 2005, 3, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. Qualitative research in health care. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ 2000, 320, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, V.P.; Fixson, S.K. Adopting “design thinking” in novice multidisciplinary teams: The application and limits of design methods and reflexive practices. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.M.; Armstrong, J.; Buckley, A.; Sherry, J.; Young, T.; Foliaki, S.; James-Hohaia, T.M.; Theadom, A.; McPherson, K.M. Encouraging family engagement in the rehabilitation process: A rehabilitation provider’s development of support strategies for family members of people with traumatic brain injury. Disabil. Rehab. 2012, 34, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, M.; Boden, Z.V.R.; Newton, E. On the Brink of Genuinely Collaborative Care: Experience-Based Co-Design in Mental Health. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, R.; Crawford, L.; Ward, S. Fundamental uncertainties in projects and the scope of project management. Int. J. Project Manag. 2006, 24, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M.; Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richards, D.A. The critical importance of patient and public involvement for research into complex interventions. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods; Richards, D.A., Hallberg, I.R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Savigny, D.; Taghreed, A. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. In Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lenfle, S. Exploration and project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M.; Savage, G. Project Stakeholder Management—Past and Present. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, T.; Hällgren, M.; Nilsson, A.; Söderholm, A. Project-as-Practice: In Search of Project Management Research That Matters. Proj. Manag. J. 2010, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahmoud-Jouini, S.; Midler, C.; Silberzahn, P. Contributions of Design Thinking to Project Management in an Innovation Context. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 47, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Maslin-Prothero, S. The involvement of users and carers in health and social research: The realities of inclusion and engagement. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participation Type | Character of Stakeholder Involvement | Relationship (Researcher and Stakeholder) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Co-option | Token; representatives are chosen, but no real action | On |

| 2. Compliance | Tasks are assigned, with incentives; researchers decide agenda and direct the process | For |

| 3. Consultation | Stakeholders’ opinions are asked, researchers analyze and decide on a course of action | For/with |

| 4. Cooperation | Stakeholders work together with researchers to determine priorities; responsibility remains with researchers for directing the process | With |

| 5. Co-learning | Stakeholders and researchers share their knowledge to create new understanding, and work together to from action plans with researcher facilitation | With/by |

| 6. Collective action | Stakeholders set their own agenda and mobilize to carry it out, in the absence of outside researchers or facilitators | By |

| Service provider as individual co-researcher | Time |

|

| Personal development |

| |

| Individual appreciation |

| |

| Service providers as professional team | Time |

|

| Resources |

| |

| Professional improvements (knowledge, skills) |

| |

| Communication |

| |

| Structured caregiver support (concept) |

| |

| Obtain professional satisfaction |

| |

| Service receiver * (family caregiver) | Time |

|

| Individualized and improved support |

| |

| Resources |

| |

| Communication improvements |

| |

| Satisfaction |

|

| Year 2017 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | June | July | August | September | |||||||||||

| Week | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 |

| Service provider (multidisciplinary team) | |||||||||||||||

| Medical doctors | FG | ||||||||||||||

| Nurses | FG | ||||||||||||||

| Therapists (physio/ergo/speech) | FG | ||||||||||||||

| Neuro-psychologist | |||||||||||||||

| Social workers | I | ||||||||||||||

| Case managers | I | ||||||||||||||

| Service receiver (family caregiver) | |||||||||||||||

| Experienced caregivers | ST | ||||||||||||||

| New caregivers | I | ||||||||||||||

| Broader perspective (hospital-intern) | |||||||||||||||

| Nursing students | FG | ||||||||||||||

| Pastor | I | ||||||||||||||

| Head nurse | I | ||||||||||||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorant, E.; Krieger, T. Contextual Exploration of a New Family Caregiver Support Concept for Geriatric Settings Using a Participatory Health Research Strategy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121467

Dorant E, Krieger T. Contextual Exploration of a New Family Caregiver Support Concept for Geriatric Settings Using a Participatory Health Research Strategy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(12):1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121467

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorant, Elisabeth, and Theresia Krieger. 2017. "Contextual Exploration of a New Family Caregiver Support Concept for Geriatric Settings Using a Participatory Health Research Strategy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 12: 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121467