From Protein Engineering to Immobilization: Promising Strategies for the Upgrade of Industrial Enzymes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

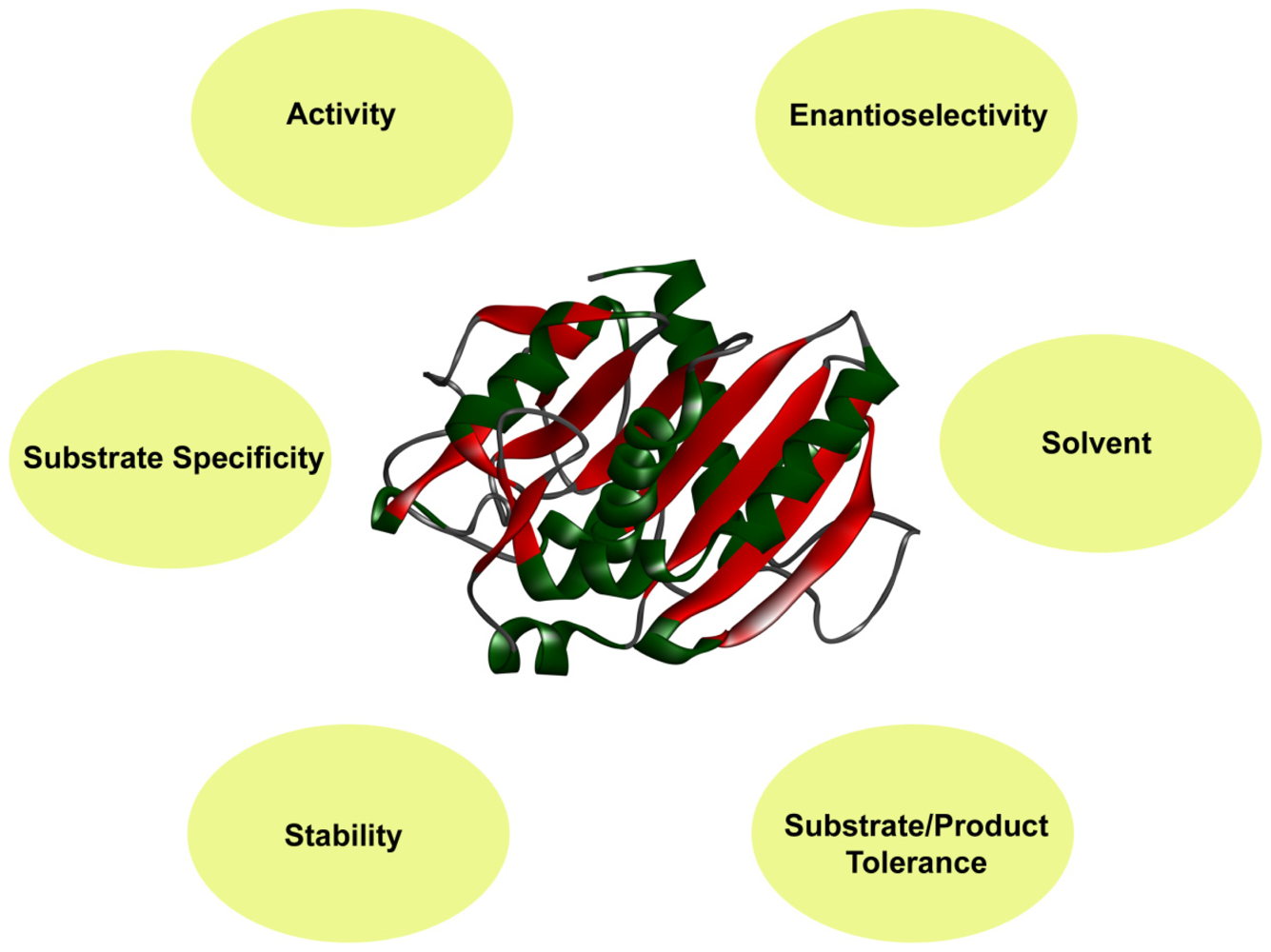

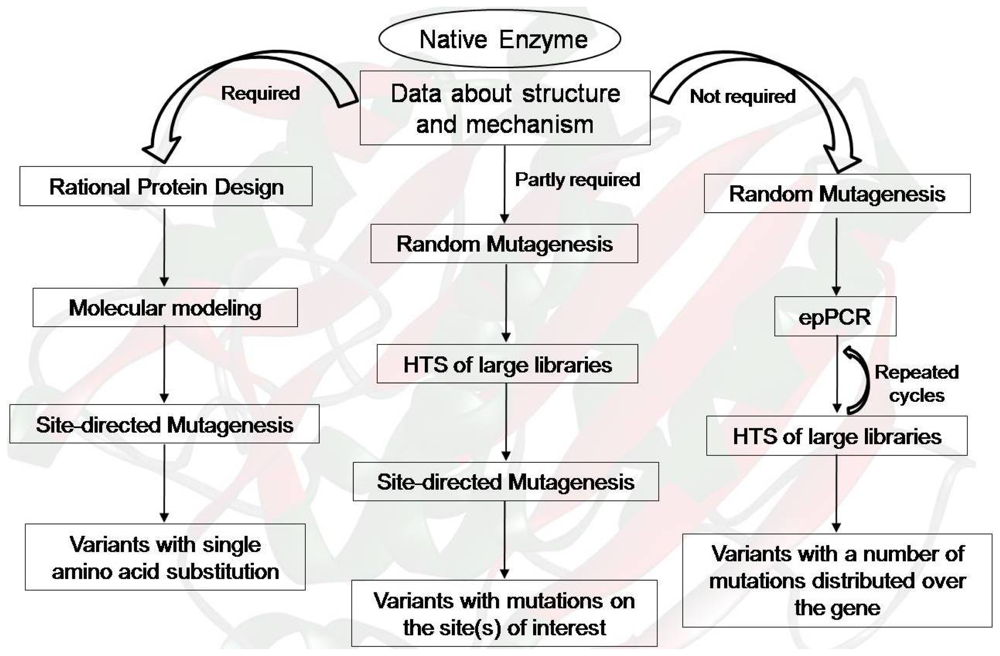

2. Protein Engineering to Upgrade Industrial Enzymes

2.1. Activity

2.2. Thermal Stability

2.3. Solvent Stability

2.4. Substrate Specificity

2.5. A Way Forward: Hybrid Approaches

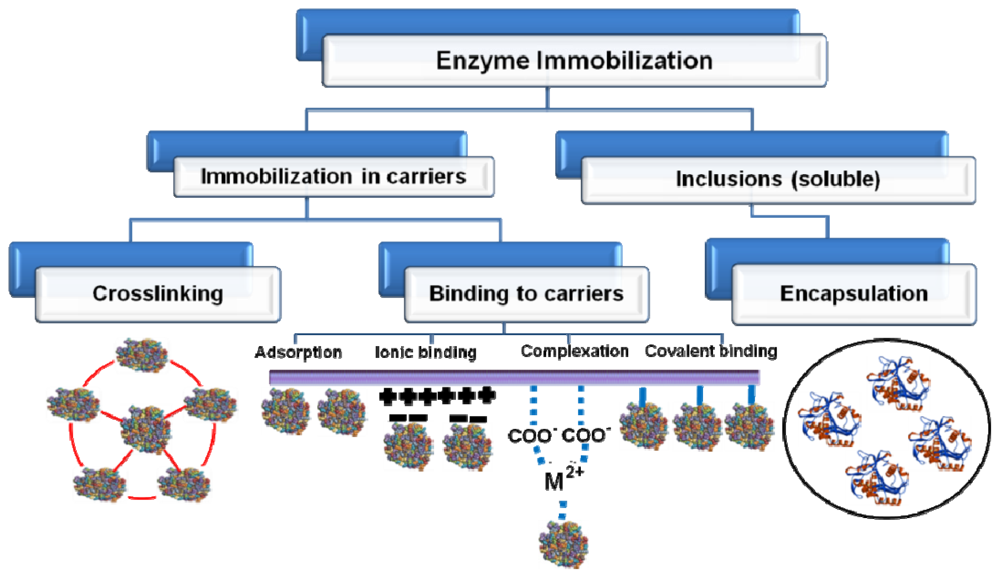

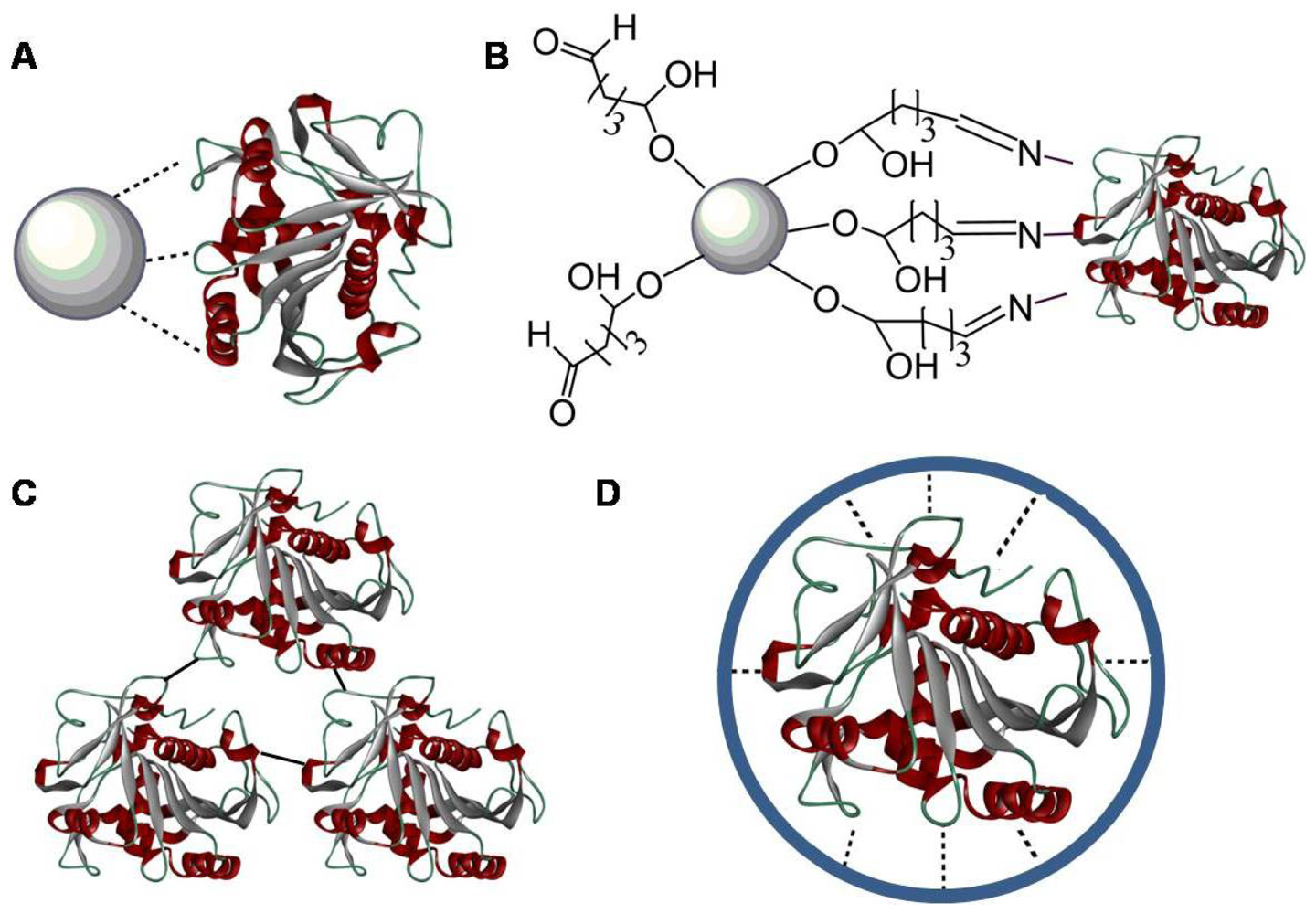

3. Immobilization to Upgrade Industrial Enzymes

3.1. Activity

3.2. Thermal Stability

3.3. Solvent Stability

3.4. Selectivity

3.5. Substrate Tolerance

3.6. Multi-Step Reactions

3.7. Advances in Enzyme Immobilization

3.7.1. New Technology for Enzyme Immobilization

3.7.1.1. Microwave Irradiation

3.7.1.2. Photoimmobilization Technology

3.7.1.3. Enzymatic Immobilization of Enzyme

3.7.1.4. Controlled Immobilization of Enzyme onto Porous Materials

3.7.2. Recommendation for the Future of Immobilization Technology

3.8. Integration of Different Techniques

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Adamczak, M.; Sajja, K.H. Strategies for improving enzymes for efficient biocatalysis. Food Technol. Biotechnol 2004, 42, 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz, M.T.; Carballeira, J.D.; Vogel, A. Iterative saturation mutagenesis on the basis of B factors as a strategy for increasing protein thermostability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45, 7745–7751. [Google Scholar]

- Bommarius, A.S.; Riebel-Bommarius, B.R. Biocatalysis: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004; p. 611. [Google Scholar]

- Katchalski-Katzir, E.; Kraemer, D.M. Eupergit C, a carrier for immobilization of enzymes of industrial potential. J. Mol. Catal. B 2000, 10, 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Straathof, A.J.J.; Panke, S.; Schmid, A. The production of fine chemicals by biotransformations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2002, 13, 548–556. [Google Scholar]

- Polizzi, K.M.; Bommarius, A.S.; Broering, J.M.; Chaparro-Riggers, J.F. Stability of biocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2007, 11, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- May, O.; Nguyen, P.T.; Arnold, F.H. Inverting enantioselectivity by directed evolution of hydantoinase for improved production of l-methionine. Nat. Biotechnol 2000, 18, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.W.; Lee, S.; Auh, J.H.; Yoo, S.S.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.T.; Rho, H.J.; Choi, J.H.; et al. Modulation of cyclizing activity and thermostability of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase and its application as an antistaling enzyme. J. Agric. Food Chem 2002, 50, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Suen, W.C.; Windsor, W.; Xiao, L.; Madison, V.; Zaks, A. Improving tolerance of Candida antarctica lipase B towards irreversible thermal inactivation through directed evolution. Protein Eng 2003, 16, 599–605. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.J.; Domann, S.; Nelson, A.; Berry, A. Modifying the stereochemistry of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction by directed evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3143–3148. [Google Scholar]

- Sriprapundh, D.; Vieille, C.; Zeikus, J.G. Directed evolution of Thermotoga neapolitana xylose isomerase: High activity on glucose at low temperature and low pH. Protein Eng 2003, 16, 683–690. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veen, B.A.; Potocki-Veronese, G.; Albenne, C.; Joucla, G.; Monsan, P.; Remaud-Simeon, M. Combinatorial engineering to enhance amylosucrase performance: Construction, selection, and screening of variant libraries for increased activity. FEBS Lett 2004, 560, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, D.; Akumanyi, N.; Hurtado-Guerrero, R.; Dawkes, H.; Knowles, P.F.; Phillips, S.E.; McPherson, M.J. Structural and kinetic studies of a series of mutants of galactose oxidase identified by directed evolution. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2004, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Berry, A. A thermostable variant of fructose bisphosphate aldolase constructed by directed evolution also shows increased stability in organic solvents. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2004, 17, 689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, T.N.; Chen, J.L.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, N.S.; Shyur, L.F. A truncated Fibrobacter succinogenes 1,3–1,4-β-d-glucanase with improved enzymatic activity and thermotolerance. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 9197–9205. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, R.; Nakagawa, Y.; Hiratake, J.; Sogabe, A.; Sakata, K. Directed evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipase for improved amide-hydrolyzing activity. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2005, 18, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tobe, S.; Shimogaki, H.; Ohdera, M.; Asai, Y.; Oba, K.; Iwama, M.; Irie, M. Expression of Bacillus protease (Protease BYA) from Bacillus sp. Y in Bacillus subtilis and enhancement of its specific activity by site-directed mutagenesis-improvement in productivity of detergent enzyme. Biol. Pharm. Bull 2006, 29, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Suemori, A.; Iwakura, M. A systematic and comprehensive combinatorial approach to simultaneously improve the activity, reaction specificity, and thermal stability of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282, 19969–19978. [Google Scholar]

- Fenel, F.; Zitting, A.J.; Kantelinen, A. Increased alkali stability in Trichoderma reesei endo-1,4-β-xylanase II by site directed mutagenesis. J. Biotechnol 2006, 121, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.; Lamsa, M.; Frandsen, T.P.; Spendler, T.; Harris, P.; Sloma, A.; Xu, F.; Nielsen, J.B.; Cherry, J.R. Directed evolution of a maltogenic α-amylase from Bacillus sp. TS-25. J. Biotechnol 2008, 134, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dumon, C.; Varvak, A.; Wall, M.A.; Flint, J.E.; Lewis, R.J.; Lakey, J.H.; Morland, C.; Luginbuhl, P.; Healey, S.; Todaro, T.; et al. Engineering hyperthermostability into a GH11 xylanase is mediated by subtle changes to protein structure. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 22557–22564. [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa, K.; Ichiyanagi, A.; Kajiyama, N. Enhancement of thermostability of fungal deglycating enzymes by directed evolution. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2008, 78, 775–781. [Google Scholar]

- Belien, T.; Joye, I.J.; Delcour, J.A.; Courtin, C.M. Computational design-based molecular engineering of the glycosyl hydrolase family 11 B. subtilis XynA endoxylanase improves its acid stability. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2009, 22, 587–596. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.Q.; Song, S.; Fang, N.; Liang, X.; Zhu, H.; Tang, X.F.; Tang, B. Improvement of low-temperature caseinolytic activity of a thermophilic subtilase by directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2009, 104, 862–870. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Farinas, E.T. Directed evolution of CotA laccase for increased substrate specificity using Bacillus subtilis spores. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2010, 23, 679–682. [Google Scholar]

- Spadiut, O.; Nguyen, T.T.; Haltrich, D. Thermostable variants of pyranose 2-oxidase showing altered substrate selectivity for glucose and galactose. J. Agric. Food Chem 2010, 58, 3465–3471. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Yi, Z.L.; Pei, X.Q.; Wu, Z.L. Improving the thermostability of Geobacillus stearothermophilus xylanase XT6 by directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis. Bioresour. Technol 2010, 101, 9272–9278. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos-Jaimes, I.; Mora-Lugo, R.; Calcagno, M.L.; Farres, A. Kinetic studies of Gly28:Ser mutant form of Bacillus pumilus lipase: Changes in kcat and thermal dependence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 2222–2227. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Lv, W.; Ma, C.; Lou, Z.; Dai, Y. Construction and characterization of a fusion β-1,3–1,4-glucanase to improve hydrolytic activity and thermostability. Biotechnol. Lett 2011, 33, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.G.; Jang, M.K.; Jeon, M.J.; Jang, H.J.; Lee, S.H. Improvement in the catalytic activity of β-agarase AgaA from Zobellia galactanivorans by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2011, 21, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Theriot, C.M.; Semcer, R.L.; Shah, S.S.; Grunden, A.M. Improving the catalytic activity of hyperthermophilic Pyrococcus horikoshii prolidase for detoxification of organophosphorus nerve agents over a broad range of temperatures. Archaea 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.W.; Pan, T.M. Substitution of Asp189 residue alters the activity and thermostability of Geobacillus sp. NTU 03 lipase. Biotechnol. Lett 2011, 33, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson, C.A.; Cappuccilli, G.; Odineca, T.; Bozic, M.; Behnke, C.A.; Mendez, M.; Coleman, W.J.; Crea, R. Engineering highly thermostable xylanase variants using an enhanced combinatorial library method. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2011, 24, 597–605. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mabrouk, S.; Aghajari, N.; Ben Ali, M.; Ben Messaoud, E.; Juy, M.; Haser, R.; Bejar, S. Enhancement of the thermostability of the maltogenic amylase MAUS149 by Gly312Ala and Lys436Arg substitutions. Bioresour. Technol 2011, 102, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, W. Improvement of the thermostability and enzymatic activity of cholesterol oxidase by site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Lett 2011, 33, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Q.A.; Joo, J.C.; Yoo, Y.J.; Kim, Y.H. Development of thermostable Candida antarctica lipase B through novel in silico design of disulfide bridge. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2012, 109, 867–876. [Google Scholar]

- Mollania, N.; Khajeh, K.; Ranjbar, B.; Hosseinkhani, S. Enhancement of a bacterial laccase thermostability through directed mutagenesis of a surface loop. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2011, 49, 446–452. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.G.; Ju, Y.H.; Yeom, S.J.; Oh, D.K. Improvement in the thermostability of d-psicose 3-epimerase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens by random and site-directed mutagenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2011, 77, 7316–7320. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.W.; Cheng, Y.S.; Ko, T.P.; Lin, C.Y.; Lai, H.L.; Chen, C.C.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, C.H.; Zou, P.; et al. Rational design to improve thermostability and specific activity of the truncated Fibrobacter succinogenes 1,3–1,4-β-d-glucanase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2012, 94, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.H.; Hu, B.; Xu, Y.J.; Bo, J.X.; Fan, S.; Wang, J.L.; Lu, F.P. Improvement of the acid stability of Bacillus licheniformis α amylase by error-prone PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol 2012, 113, 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Wang, N.S.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Structure-based engineering of methionine residues in the catalytic cores of alkaline amylase from Alkalimonas amylolytica for improved oxidative stability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2012, 78, 7519–7526. [Google Scholar]

- Srikrishnan, S.; Randall, A.; Baldi, P.; Da Silva, N.A. Rationally selected single-site mutants of the Thermoascus aurantiacus endoglucanase increase hydrolytic activity on cellulosic substrates. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2012, 109, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka, T.; Yasutake, Y.; Nishiya, Y.; Tamura, T. Structure-guided mutagenesis for the improvement of substrate specificity of Bacillus megaterium glucose 1-dehydrogenase IV. FEBS J 2012, 279, 3264–3275. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Guo, Q.; Wei, Y.; Xu, H.; Huang, R. Enhancement of pH stability and activity of glycerol dehydratase from Klebsiella pneumoniae by rational design. Biotechnol. Lett 2012, 34, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, P.H.; Illias, R.M.; Goh, K.M. Rational mutagenesis of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase at the calcium binding regions for enhancement of thermostability. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 5307–5323. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.H. Engineering a large protein by combined rational and random approaches: Stabilizing the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiose phosphorylase. Mol. Biosyst 2012, 8, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Dutt, S.; Bagler, G.; Ahuja, P.S.; Kumar, S. Engineering a thermo-stable superoxide dismutase functional at sub-zero to >50 °C, which also tolerates autoclaving. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 387:1–387:8. [Google Scholar]

- Anbar, M.; Gul, O.; Lamed, R.; Sezerman, U.O.; Bayer, E.A. Improved thermostability of Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase Cel8A by using consensus-guided mutagenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2012, 78, 3458–3464. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z. Truncation of the cellulose binding domain improved thermal stability of endo-β-1,4-glucanase from Bacillus subtilis JA18. Bioresour. Technol 2009, 100, 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Spadiut, O.; Radakovits, K.; Pisanelli, I.; Salaheddin, C.; Yamabhai, M.; Tan, T.C.; Divne, C.; Haltrich, D. A thermostable triple mutant of pyranose 2-oxidase from Trametes multicolor with improved properties for biotechnological applications. Biotechnol. J 2009, 4, 525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Rha, E.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.L.; Hong, S.P.; Sung, M.H.; Song, J.J.; Lee, S.G. Simultaneous improvement of catalytic activity and thermal stability of tyrosine phenol-lyase by directed evolution. FEBS J 2009, 276, 6187–6194. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Engineering of protease-resistant phytase from Penicillium sp.: High thermal stability, low optimal temperature and pH. J. Biosci. Bioeng 2010, 110, 638–645. [Google Scholar]

- Kotzia, G.A.; Labrou, N.E. Engineering thermal stability of l-asparaginase by in vitro directed evolution. FEBS J 2009, 276, 1750–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Z.L.; Pei, X.Q.; Wu, Z.L. Introduction of glycine and proline residues onto protein surface increases the thermostability of endoglucanase CelA from Clostridium thermocellum. Bioresour. Technol 2011, 102, 3636–3638. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, X.Q.; Yi, Z.L.; Tang, C.G.; Wu, Z.L. Three amino acid changes contribute markedly to the thermostability β-glucosidase BglC from Thermobifida fusca. Bioresour. Technol 2011, 102, 3337–3342. [Google Scholar]

- Damnjanovic, J.; Takahashi, R.; Suzuki, A.; Nakano, H.; Iwasaki, Y. Improving thermostability of phosphatidylinositol-synthesizing Streptomyces phospholipase D. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2012, 25, 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.L.; Chang, C.K.; Jeng, W.Y.; Wang, A.H.; Liang, P.H. Mutations in the substrate entrance region of β-glucosidase from Trichoderma reesei improve enzyme activity and thermostability. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2012, 25, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Mohammad, O.; Singh, R.; Kaur, J. Engineering of a metagenome derived lipase toward thermal tolerance: Effect of asparagine to lysine mutation on the protein surface. Gene 2012, 491, 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, S.; Pardo, I.; Canas, A.I.; Molina, P.; Record, E.; Martinez, A.T.; Martinez, M.J.; Alcalde, M. Engineering platforms for directed evolution of Laccase from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2012, 78, 1370–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.B.; Pei, X.Q.; Wu, Z.L. Multiple amino acid substitutions significantly improve the thermostability of feruloyl esterase A from Aspergillus niger. Bioresour. Technol 2012, 117, 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Brode, P.F., III; Erwin, C.R.; Rauch, D.S.; Barnett, B.L.; Armpriester, J.M.; Wang, E.S.; Rubingh, D.N. Subtilisin BPN’ variants: Increased hydrolytic activity on surface-bound substrates via decreased surface activity. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 3162–3169. [Google Scholar]

- Rubingh, D.N. The influence of surfactants on enzyme activity. Curr. Opin. Coll. Int. Sci 1996, 1, 598–603. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, H.D.; Wohlfahrt, G.; McCarthy, J.E.; Schomburg, D.; Schmid, R.D. Analysis of the catalytic mechanism of a fungal lipase using computer-aided design and structural mutants. Protein Eng 1996, 9, 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelle, M.; Holmquist, M.; Clausen, I.G.; Patkar, S.; Svendsen, A.; Hult, K. The role of Glu87 and Trp89 in the lid of Humicola lanuginosa lipase. Protein Eng 1996, 9, 519–524. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, S.; Lange, N.K.; Nissen, A.M. Novel industrial enzyme applications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1995, 750, 376–390. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, T.W. Enzyme Technology for Pulp Bleaching and Deinking; International Business Communications: Southbourough, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Koivula, A.; Reinikainen, T.; Ruohonen, L.; Valkeajarvi, A.; Claeyssens, M.; Teleman, O.; Kleywegt, G.J.; Szardenings, M.; Rouvinen, J.; Jones, T.A.; et al. The active site of Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolase II: The role of tyrosine 169. Protein Eng 1996, 9, 691–699. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, T.W. Biochemistry and genetics of microbial xylanases. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 1996, 7, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, J.R.; Lamsa, M.H.; Schneider, P.; Vind, J.; Svendsen, A.; Jones, A.; Pedersen, A.H. Directed evolution of a fungal peroxidase. Nat. Biotechnol 1999, 17, 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.; Sieber, V.; Schmid, F.X. In-vitro selection of highly stabilized protein variants with optimized surface. J. Mol. Biol 2001, 309, 717–726. [Google Scholar]

- Palackal, N.; Brennan, Y.; Callen, W.N.; Dupree, P.; Frey, G.; Goubet, F.; Hazlewood, G.P.; Healey, S.; Kang, Y.E.; Kretz, K.A.; et al. An evolutionary route to xylanase process fitness. Protein Sci 2004, 13, 494–503. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Dannert, C.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution of industrial enzymes. Trends Biotechnol 1999, 17, 135–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution converts subtilisin E into a functional equivalent of thermitase. Protein Eng 1999, 12, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, K.; Wintrode, P.L.; Grayling, R.A.; Rubingh, D.N.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution study of temperature adaptation in a psychrophilic enzyme. J. Mol. Biol 2000, 297, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenson, A.; Schauerte, J.A.; Giver, L.; Arnold, F.H. Tryptophan phosphorescence study of enzyme flexibility and unfolding in laboratory-evolved thermostable esterases. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 4658–4665. [Google Scholar]

- Giver, L.; Gershenson, A.; Freskgard, P.O.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution of a thermostable esterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 12809–12813. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T.; Yasugi, M.; Arisaka, F.; Yamagishi, A.; Oshima, T. Adaptation of a thermophilic enzyme, 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase, to low temperatures. Protein Eng 2001, 14, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tamakoshi, M.; Nakano, Y.; Kakizawa, S.; Yamagishi, A.; Oshima, T. Selection of stabilized 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae using the host-vector system of an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. Extremophiles 2001, 5, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, F.; Vriend, G.; Veltman, O.R.; van der Vinne, B.; Venema, G.; Eijsink, V.G. Stabilization of Bacillus stearothermophilus neutral protease by introduction of prolines. FEBS Lett 1993, 317, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, J.; Vriend, G.; Dijkstra, B.W.; Veltman, O.R.; van den Burg, B.; Venema, G.; Ulbrich-Hofmann, R.; Eijsink, V.G. Extreme stabilization of a thermolysin-like protease by an engineered disulfide bond. J. Biol. Chem 1997, 272, 11152–11156. [Google Scholar]

- Veltman, O.R.; Vriend, G.; Middelhoven, P.J.; van den Burg, B.; Venema, G.; Eijsink, V.G. Analysis of structural determinants of the stability of thermolysin-like proteases by molecular modelling and site-directed mutagenesis. Protein Eng 1996, 9, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Burg, B.; Vriend, G.; Veltman, O.R.; Venema, G.; Eijsink, V.G. Engineering an enzyme to resist boiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2056–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, S.; Kakuta, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Hikichi, K.; Kuhara, S.; Yamasaki, N.; Kimura, M. Glycine-15 in the bend between two α-helices can explain the thermostability of DNA binding protein HU from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, S.; Kanaya, S.; Nakamura, H. Thermostabilization of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI by replacing left-handed helical Lys95 with Gly or Asn. J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267, 22014–22017. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B.W.; Nicholson, H.; Becktel, W.J. Enhanced protein thermostability from site-directed mutations that decrease the entropy of unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 6663–6667. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Aparicio, J.; Hermoso, J.A.; Martínez-Ripoll, M.; González, B.; López-Camacho, C.; Polaina, J. Structural basis of increased resistance to thermal denaturation induced by single amino acid substitution in the sequence of β-glucosidase A from Bacillus polymyxa. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma 1998, 33, 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, M.K.; Moon, H.J.; Jeya, M.; Lee, J.K. Cloning and characterization of a thermostable xylitol dehydrogenase from Rhizobium etli CFN42. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2010, 87, 571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Wintrode, P.L.; Arnold, F.H. Temperature adaptation of enzymes: Lessons from laboratory evolution. Adv. Protein Chem 2000, 55, 161–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J.; Baase, W.A.; Shoichet, B.K.; Wilson, K.P.; Matthews, B.W. Enhancement of protein stability by the combination of point mutations in T4 lysozyme is additive. Protein Eng 1995, 8, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, M.; Loch, C.; Middendorf, A.; Studer, D.; Lassen, S.F.; Pasamontes, L.; van Loon, A.P.; Wyss, M. The consensus concept for thermostability engineering of proteins: Further proof of concept. Protein Eng 2002, 15, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, S.; Marx, J.C.; Gerday, C.; Feller, G. Activity-stability relationships in extremophilic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 7891–7896. [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren, M.; Gualfetti, P.J.; Shaw, A.; Gross, L.S.; Saldajeno, M.; Day, A.G.; Jones, T.A.; Mitchinson, C. Comparison of family 12 glycoside hydrolases and recruited substitutions important for thermal stability. Protein Sci 2003, 12, 848–860. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.C.; Zeelen, J.P.; Neubauer, G.; Vriend, G.; Backmann, J.; Michels, P.A.; Lambeir, A.M.; Wierenga, R.K. Structural and mutagenesis studies of leishmania triosephosphate isomerase: A point mutation can convert a mesophilic enzyme into a superstable enzyme without losing catalytic power. Protein Eng 1999, 12, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, J.; Shimahara, H.; Mizutani, M.; Uchiyama, S.; Arai, H.; Ishii, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ferguson, S.J.; Sambongi, Y.; Igarashi, Y. Stabilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytochrome c551 by systematic amino acid substitutions based on the structure of thermophilic Hydrogenobacter thermophilus cytochrome c552. J. Biol. Chem 1999, 274, 37533–37537. [Google Scholar]

- Khmelnitsky, Y.L.; Rich, J.O. Biocatalysis in nonaqueous solvents. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 1999, 3, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, F.H. Engineering enzymes for non-aqueous solvents. Trends. Biotechnol 1990, 8, 244–249. [Google Scholar]

- Dordick, J.S. Enzymatic catalysis in monophasic organic solvents. Enzyme Microb. Technol 1989, 11, 194–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.H.; Chen, S.T.; Hennen, W.J.; Bibbs, J.A.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, J.L.C.; Pantoliano, M.W.; Whitlow, M.; Bryan, P.N. Enzymes in organic synthesis: Use of subtilisin and a highly stable mutant derived from multiple site-specific mutations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 945–953. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.Q.; Arnold, F.H. Enzyme engineering for nonaqueous solvents: Random mutagenesis to enhance activity of subtilisin E in polar organic media. Biotechnology 1991, 9, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, C.; Chen, K.; Arnold, F.H. Random mutagenesis to enhance the activity of subtilisin in organic solvents: Characterization of Q103R subtilisin E. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1992, 39, 658–662. [Google Scholar]

- Pantoliano, M.W. Proteins designed for challenging environments and catalysis in organic solvents. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 1992, 2, 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.C.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution of a p-nitrobenzyl esterase for aqueous-organic solvents. Nat. Biotechnol 1996, 14, 458–467. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, P.; van Dam, M.E.; Robinson, A.C.; Chen, K.; Arnold, F.H. Stabilization of substilisin E in organic solvents by site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1992, 39, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.K.; Rhee, J.S. Enhancement of stability and activity of phospholipase A1 in organic solvents by directed evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1547, 370–378. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, B.; Quan, S.; Arnold, F.H. Functional expression and stabilization of horseradish peroxidase by directed evolution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2001, 76, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Liebeton, K.; Zonta, A.; Schimossek, K.; Nardini, M.; Lang, D.; Dijkstra, B.W.; Reetz, M.T.; Jaeger, K.E. Directed evolution of an enantioselective lipase. Chem. Biol 2000, 7, 709–718. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, K.E.; Eggert, T.; Eipper, A.; Reetz, M.T. Directed evolution and the creation of enantioselective biocatalysts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2001, 55, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Nardini, M.; Lang, D.A.; Liebeton, K.; Jaeger, K.E.; Dijkstra, B.W. Crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipase in the open conformation. The prototype for family I.1 of bacterial lipases. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 31219–31225. [Google Scholar]

- Raillard, S.; Krebber, A.; Chen, Y.; Ness, J.E.; Bermudez, E.; Trinidad, R.; Fullem, R.; Davis, C.; Welch, M.; Seffernick, J.; et al. Novel enzyme activities and functional plasticity revealed by recombining highly homologous enzymes. Chem. Biol 2001, 8, 891–898. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, S.; Machajewski, T.D.; Mak, C.C.; Wong, C. Directed evolution of d-2-keto-3-deoxy-6- phosphogluconate aldolase to new variants for the efficient synthesis of d- and l-sugars. Chem. Biol 2000, 7, 873–883. [Google Scholar]

- Wymer, N.; Buchanan, L.V.; Henderson, D.; Mehta, N.; Botting, C.H.; Pocivavsek, L.; Fierke, C.A.; Toone, E.J.; Naismith, J.H. Directed evolution of a new catalytic site in 2-keto-3- deoxy-6-phosphogluconate aldolase from Escherichia coli. Structure 2001, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga, H.; Goto, M.; Furukawa, K. Emergence of multifunctional oxygenase activities by random priming recombination. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 22500–22506. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Simurdiak, M.; Zhao, H. Reconstitution and characterization of aminopyrrolnitrin oxygenase, a rieske N-oxygenase that catalyzes unusual arylamine oxidation. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 36719–36727. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Zhao, H. Mechanistic studies on the conversion of arylamines into arylnitro compounds by aminopyrrolnitrin oxygenase: Identification of intermediates and kinetic studies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45, 622–625. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Ang, E.L.; Zhao, H. Probing the substrate specificity of aminopyrrolnitrin Oxygenase (PrnD) by mutational analysis. J. Bacteriol 2006, 188, 6179–6183. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.J.; Foo, J.L.; Tokuriki, N.; Afriat, L.; Carr, P.D.; Kim, H.K.; Schenk, G.; Tawfik, D.S.; Ollis, D.L. Conformational sampling, catalysis, and evolution of the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21631–21636. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, J.L.; Jackson, C.J.; Carr, P.D.; Kim, H.K.; Schenk, G.; Gahan, L.R.; Ollis, D.L. Mutation of outer-shell residues modulates metal ion co-ordination strength in a metalloenzyme. Biochem. J 2010, 429, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, R.; Deane, C.M. Protein structure prediction begins well but ends badly. Proteins 2010, 78, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Protein structure prediction: When is it useful? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2009, 19, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Progress and challenges in protein structure prediction. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2008, 18, 342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.D.; Jewsbury, P.J.; Essex, J.W. A review of protein-small molecule docking methods. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 2002, 16, 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, J.L.; Ching, C.B.; Chang, M.W.; Leong, S.S. The imminent role of protein engineering in synthetic biology. Biotechnol. Adv 2012, 30, 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.J.; Weir, K.; Herlt, A.; Khurana, J.; Sutherland, T.D.; Horne, I.; Easton, C.; Russell, R.J.; Scott, C.; Oakeshott, J.G. Structure-based rational design of a phosphotriesterase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2009, 75, 5153–5156. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.J.; Foo, J.L.; Kim, H.K.; Carr, P.D.; Liu, J.W.; Salem, G.; Ollis, D.L. In crystallo capture of a Michaelis complex and product-binding modes of a bacterial phosphotriesterase. J. Mol. Biol 2008, 375, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwumba, I.N.; Ozawa, K.; Xu, Z.Q.; Ely, F.; Foo, J.L.; Herlt, A.J.; Coppin, C.; Brown, S.; Taylor, M.C.; Ollis, D.L.; et al. Improving a natural enzyme activity through incorporation of unnatural amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Voloshchuk, N.; Montclare, J.K. Incorporation of unnatural amino acids for synthetic biology. Mol. Biosyst 2010, 6, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, L.; Levin, Y.; Katchalski, E. A water-insoluble polyanionic derivatives of trypsin, effect of the polyelectrolyte carrier on the kinetic behaviour of the bound trypsin. Biochemistry 1964, 3, 1914–1919. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, M.; Hatanaka, C.; Goto, M. Immobilization of surfactant-lipase complexes and their high heat resistance in organic media. Biochem. Eng. J 2005, 24, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cabana, H.; Jones, J.P.; Agathos, S.N. Preparation and characterization of cross-linked laccase aggregates and their application to the elimination of endocrine disrupting chemicals. J. Biotechnol 2007, 132, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha, K.; Abraham, T.E. Preparation and characterization of cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEA) of subtilisin for controlled release applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2008, 43, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh, S.L.; Bilek, M.M.; Nosworthy, N.J.; Kondyurin, A.; dos Remedios, C.G.; McKenzie, D.R. A comparison of covalent immobilization and physical adsorption of a cellulase enzyme mixture. Langmuir 2010, 26, 14380–14388. [Google Scholar]

- Dickensheets, P.A.; Chen, L.F.; Tsao, G.T. Characteristics of yeast invertase immobilized on porous cellulose beads. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1977, 19, 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Turkova, J. Oriented immobilization of biologically active proteins as a tool for revealing protein interactions and function. J. Chromatogr. B 1999, 722, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.F. A comparison of various commercially-available liquid chromatographic supports for immobilization of enzymes and immunoglobulins. Analytica. Chimica. Acta 1985, 172, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Aloulou, A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Fernandez, S.; Oosterhout, D.V.; Puccinelli, D.; Carrière, F. Exploring the specific features of interfacial enzymology based on lipase studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1761, 995–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M. Lipases enantioselectivity alteration by immobilization techniques. Curr. Bioact. Compd 2008, 4, 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, L.; Brzozowski, A.M.; Derewenda, Z.S.; Dodson, E.; Dodson, G.; Tolley, S.; Turkenburg, J.P.; Christiansen, L.; Huge-Jensen, B.; Norskov, L.; et al. A serine protease triad forms the catalytic centre of a triacylglycerol lipase. Nature 1990, 343, 767–770. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski, A.M.; Derewenda, U.; Derewenda, Z.S.; Dodson, G.G.; Lawson, D.M.; Turkenburg, J.P.; Bjorkling, F.; Huge-Jensen, B.; Patkar, S.A.; Thim, L. A model for interfacial activation in lipases from the structure of a fungal lipase-inhibitor complex. Nature 1991, 351, 491–494. [Google Scholar]

- Derewenda, U.; Brzozowski, A.M.; Lawson, D.M.; Derewenda, Z.S. Catalysis at the interface: The anatomy of a conformational change in a triglyceride lipase. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Kanori, M.; Hori, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Hirose, Y.; Naoshima, Y. A new inorganic ceramic support, Toyonite and the reactivity and enantioselectivity of the immobilised lipase. J. Mol. Catal 2000, 9, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.; Zhu, G.; Wang, P. Catalytic behaviors of enzymes attached to nanoparticles: The effect of particle mobility. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2003, 84, 406–414. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, M.; Zhang, X.; Kurabi, A.; Gilkes, N.; Mabee, W.; Saddler, J. Immobilization of β-glucosidase on Eupergit C for lignocellulose hydrolysis. Biotechnol. Lett 2006, 28, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Singh, S.P.; Arya, S.K.; Gupta, V.; Datta, M.; Singh, S.; Malhotra, B.D. Application of thiolated gold nanoparticles for the enhancement of glucose oxidase activity. Langmuir 2007, 23, 3333–3337. [Google Scholar]

- Prakasham, R.S.; Devi, G.S.; Laxmi, K.R.; Rao, C.S. Novel synthesis of ferric impregnated silica nanoparticles and their evaluation as a matrix for enzyme immobilization. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 3842–3847. [Google Scholar]

- Neri, D.F.M.; Balcäo, V.M.; Costa, R.S.; Rocha, I.C.A.P.; Ferreira, E.M.F.C.; Torres, D.P.M.; Rodrigues, L.R.M.; Carvalho, L.B.; Teixeira, J.A. Galacto-oligosaccharides production during lactose hydrolysis by free Aspergillus oryzae β-galactosidase and immobilized on magnetic polysiloxane-polyvinyl alcohol. Food Chem 2009, 115, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Konwarh, R.; Karak, N.; Rai, S.K.; Mukherjee, A.K. Polymer-assisted iron oxide magnetic nanoparticle immobilized keratinase. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 225107–225117. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Lu, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, Y. Immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on nanoporous copper and its potential applications. Bioresour. Technol 2010, 101, 9415–9420. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemifard, N.; Mohsenifar, A.; Ranjbar, B.; Allameh, A.; Lotfi, A.S.; Etemadikia, B. Fabrication and kinetic studies of a novel silver nanoparticles-glucose oxidase bioconjugate. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 675, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.K.; Zhang, Y.W.; Nguyen, N.P.; Jeya, M.; Lee, J.K. Covalent immobilization of β-1,4-glucosidase from Agaricus arvensis onto functionalized silicon oxide nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2010, 89, 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Jeya, M.; Lee, J.K. Enhanced activity and stability of l-arabinose isomerase by immobilization on aminopropyl glass. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2011, 89, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Ahmed, S. Silver nanoparticle (AgNPs) doped gum acacia-gelatin-silica nanohybrid: An effective support for diastase immobilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2011, 50, 353–361. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Su, R.X.; Qi, W.; Zhang, M.J.; He, Z.M. Preparation and activity of bubbling-immobilized cellobiase within chitosan-alginate composite. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol 2010, 40, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, S.A.; Husain, Q. Potential applications of enzymes immobilized on/in nano materials: A review. Biotechnol. Adv 2012, 30, 512–523. [Google Scholar]

- Nwagu, T.N.; Okolo, B.N.; Aoyagi, H. Stabilization of a raw starch digesting amylase from Aspergillus carbonarius via immobilization on activated and non-activated agarose gel. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2012, 28, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q.; Chen, F.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Zeng, Z.; Xie, T. Stable and efficient immobilization technique of aldolase under consecutive microwave irradiation at low temperature. Bioresour. Technol 2011, 102, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, S.K.; Praveen Kumar, S.K.; Mulimani, V.H. Calcium alginate entrapped preparation of α-galactosidase: Its stability and application in hydrolysis of soymilk galactooligosaccharides. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2011, 38, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Cristovao, R.O.; Silverio, S.C.; Tavares, A.P.; Brigida, A.I.; Loureiro, J.M.; Boaventura, R.A.; Macedo, E.A.; Coelho, M.A. Green coconut fiber: A novel carrier for the immobilization of commercial laccase by covalent attachment for textile dyes decolourization. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2012, 28, 2827–2838. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, B.; Sahu, S.K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Dhara, D.; Pramanik, P. A novel approach for efficient immobilization and stabilization of papain on magnetic gold nanocomposites. Colloids Surf. B 2012, 101, 280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, M.B.; Holmberg, K. Covalent immobilization of lipase in organic solvents. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1989, 34, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuello, C.; de Miguel, R.; Gomez-Moreno, C.; Martinez-Julvez, M.; Lostao, A. An efficient method for enzyme immobilization evidenced by atomic force microscopy. Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2012, 25, 715–723. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.H.A.; van Langen, L.M.; Pereira, S.R.M.; van Rantwijk, F.; Sheldon, R.A. Evaluation of the performance of immobilized penicillin G acylase using active-site titration. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2002, 78, 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Bezbradica, D.; Mijin, D.; Mihailović, M.; Knežević-Jugović, Z. Microwave-assisted immobilization of lipase from Candida rugosa on Eupergit® supports. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol 2009, 84, 1642–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Itoyama, K.; Tokura, S.; Hayashi, T. Lipoprotein lipase immobilization onto porous chitosan beads. Biotechnol. Prog 1994, 10, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, T.; Ikada, Y. Protease immobilization onto polyacrolein microspheres. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1990, 35, 518–524. [Google Scholar]

- Itoyama, K.; Tanibe, H.; Hayashi, T.; Ikada, Y. Spacer effects on enzymatic activity of papain immobilized onto porous chitosan beads. Biomaterials 1994, 15, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Abian, O.; Wilson, L.; Mateo, C.; Fernández-Lorente, G.; Palomo, J.M.; Fernández-Lafuente, R.; Guisán, J.M.; Re, D.; Tam, A.; Daminatti, M. Preparation of artificial hyper-hydrophilic micro-environments (polymeric salts) surrounding enzyme molecules: New enzyme derivatives to be used in any reaction medium. J. Mol. Catal. B 2002, (19–20), 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bigdeli, S.; Talasaz, A.H.; Ståhl, P.; Persson, H.H.J.; Ronaghi, M.; Davis, R.W.; Nemat-Gorgani, M. Conformational flexibility of a model protein upon immobilization on self-assembled monolayers. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2008, 100, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Schmid, R.D. Carrier-Bound Immobilized Enzymes: Principles, Application and Design; Wiley-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, S.; Tumturk, H.; Hasirci, N. Stability of α-amylase immobilized on poly (methyl methacrylate-acrylic acid) microspheres. J. Biotechnol 1998, 60, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hanefeld, U.; Gardossi, L.; Magner, E. Understanding enzyme immobilisation. Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 453–468. [Google Scholar]

- Sabularse, V.C.; Tud, M.T.; Lacsamana, M.S.; Solivas, J.L. Black and white lahar as inorganic support for the immobilization of yeast invertase. ASEAN J. Sci. Technol. Dev 2005, 22, 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal, S.M.; Shankar, V. Immobilized invertase. Biotechnol. Adv 2009, 27, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.S. Can immobilization be exploited to modify enzyme activity? Trends Biotechnol 1994, 12, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, C.; Palomo, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Improvement of enzyme activity, stability and selectivity via immobilization techniques. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2007, 40, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, M.; Ohashi, K. Effect of immobilization on thermostability of lipase from Candida rugosa. Biochem. Eng. J 2003, 14, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama, S.; Noda, A.; Nakanishi, K.; Matsuno, R.; Kamikubo, T. Thermal stability of immobilized glucoamylase entrapped in polyacrylamide gels and bound to SP-Sephadex C-50. Agric. Biol. Chem 1980, 44, 2024–2054. [Google Scholar]

- Fruhwirth, G.O.; Paar, A.; Gudelj, M.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Robra, K.H.; Gübitz, G.M. An immobilised catalase peroxidase from the alkalothermophilic Bacillus SF for the treatment of textile-bleaching effluents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2002, 60, 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Cowan, D.A.; Wood, A.N.P. Hyperstabilization of a thermophilic esterase by multipoint covalent attachment. Enzyme Microb. Technol 1995, 17, 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.C.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, H.S. Production of d-p-hydroxyphenylglycine from d,l-5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)hydantoin using immobilized thermostable d-hydantoinase from Bacillus stearothermophilus SD-1. Enzyme Microb. Technol 1996, 18, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, K.; Abe, T.; Tomoaki, Y. Silicone-immobilized biocatalysts effective for bioconversions in nonaqueous media. Enzyme Microb. Technol 1992, 14, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Pedroche, J.; del Mar Yust, M.; Mateo, C.; Fernández-Lafuente, R.; Girán-Calle, J.; Alaiz, M.; Vioque, J.; Guisán, J.M.; Millán, F. Effect of the support and experimental conditions in the intensity of the multipoint covalent attachment of proteins on glyoxyl-agarose supports: Correlation between enzyme-support linkages and thermal stability. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2007, 40, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, C.; Abian, O.; Fernández-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Increase in conformational stability of enzymes immobilized on epoxy-activated supports by favoring additional multipoint covalent attachment. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2000, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Hu, X.; Cook, S.; Hwang, H.M. Influence of silica-derived nano-supporters on cellobiase after immobilization. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 2009, 158, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L.S.; Khan, F.; Micklefield, J. Selective covalent protein immobilization: Strategies and applications. Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 4025–4053. [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman, M.V.; Bayramođlu, G.; Kayaman-Apohan, N.; Güngör, A. α-Amylase immobilization on functionalized glass beads by covalent attachment. Food Chem 2007, 104, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, E.; Can, K.; Sezgin, M.; Yilmaz, M. Immobilization of Candida rugosa lipase on glass beads for enantioselective hydrolysis of racemic naproxen methyl ester. Bioresour. Technol 2011, 102, 499–506. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A., III; Oh, S.; Engler, C.R. Cellulase immobilization on Fe3O4 and characterization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1989, 33, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, J.M.; Wilson, L.; Ferrarotti, S.A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M.; Mateo, C. Stabilization of a formate dehydrogenase by covalent immobilization on highly activated glyoxyl-agarose supports. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Tardioli, P.W.; Zanin, G.M.; de Moraes, F.F. Characterization of Thermoanaerobacter cyclomaltodextrin glucanotransferase immobilized on glyoxyl-agarose. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2006, 39, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Pessela, B.C.; Mateo, C.; Fuentes, M.; Vian, A.; Garcia, J.L.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Stabilization of a multimeric β-galactosidase from Thermus sp. strain T2 by immobilization on novel heterofunctional epoxy supports plus aldehyde-dextran cross-linking. Biotechnol. Prog 2004, 20, 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- Guisán, J.M.; Polo, E.; Aguado, J.; Romero, M.D.; Álvaro, G.; Guerra, M.J. Immobilization-stabilization of thermolysin onto activated agarose gels. Biocatal. Biotransform 1997, 15, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, C.; Ballesteros, A.; Guisán, J.M. Immobilization/stabilization of lipase from Candida rugosa. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 1988, 19, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Alvaro, G.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Blanco, R.M.; Guisan, J.M. Immobilization-stabilization of penicillin G acylase from Escherichia coli. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 1990, 26, 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Guisan, J.M.; Bastida, A.; Cuesta, C.; Fernandez-Lufuente, R.; Rosell, C.M. Immobilization-stabilization of α-chymotrypsin by covalent attachment to aldehyde-agarose gels. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1991, 38, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Guisan, J.M.; Alvaro, G.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Rosell, C.M.; Garcia, J.L.; Tagliani, A. Stabilization of heterodimeric enzyme by multipoint covalent immobilization: Penicillin G acylase from Kluyvera citrophila. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1993, 42, 455–464. [Google Scholar]

- Akgöl, S.; Bayramođlu, G.; Kacar, Y.; Denizli, A.; Arýca, M.Y. Poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylateco- glycidyl methacrylate) reactive membrane utilised for cholesterol oxidase immobilisation. Polym. Int 2002, 51, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Tardioli, P.W.; Pedroche, J.; Giordano, R.L.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Hydrolysis of proteins by immobilized-stabilized alcalase-glyoxyl agarose. Biotechnol. Prog 2003, 19, 352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, C.W.; Choi, G.S.; Lee, E.K. Enzymic cleavage of fusion protein using immobilized urokinase covalently conjugated to glyoxyl-agarose. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem 2003, 37, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bayramoglu, G.; Yilmaz, M.; Arica, M.Y. Immobilization of a thermostable α-amylase onto reactive membranes: Kinetics characterization and application to continuous starch hydrolysis. Food Chem 2004, 84, 591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Danisman, T.; Tan, S.; Kacar, Y.; Ergene, A. Covalent immobilization of invertase on microporous pHEMA-GMA membrane. Food Chem 2004, 85, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- De Segura, A.G.; Alcalde, M.; Yates, M.; Rojas-Cervantes, M.L.; López-Cortés, N.; Ballesteros, A.; Plou, F.J. Immobilization of dextransucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-512F on Eupergit C Supports. Biotechnol. Prog 2004, 20, 1414–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, J.M.; Wilson, L.; Ferrarotti, S.A.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Mateo, C. Improvement of the stability of alcohol dehydrogenase by covalent immobilization on glyoxyl-agarose. J. Biotechnol 2006, 125, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarotti, S.A.; Bolivar, J.M.; Mateo, C.; Wilson, L.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Immobilization and stabilization of a cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase by covalent attachment on highly activated glyoxyl-agarose supports. Biotechnol. Prog 2006, 22, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, J.M.; Wilson, L.; Ferrarotti, S.A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M.; Mateo, C. Evaluation of different immobilization strategies to prepare an industrial biocatalyst of formate dehydrogenase from Candida boidinii. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2007, 40, 540–546. [Google Scholar]

- Arica, M.Y.; Altintas, B.; Bayramoglu, G. Immobilization of laccase onto spacer-arm attached non-porous poly(GMA/EGDMA) beads: Application for textile dye degradation. Bioresour. Technol 2009, 100, 665–669. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Tiwari, M.K.; Jeya, M.; Lee, J.K. Covalent immobilization of recombinant Rhizobium etli CFN42 xylitol dehydrogenase onto modified silica nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2010, 90, 499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Corman, M.E.; Ozturk, N.; Bereli, N.; Akgol, S.; Denizli, A. Preparation of nanoparticles which contains histidine for immobilization of Trametes versicolor laccase. J. Mol. Catal. B 2010, 63, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. Immobilization of cellulase on a reversibly soluble-insoluble support: Properties and application. J. Agric. Food Chem 2010, 58, 6741–6746. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Reinhold, J.; Woodbury, N.W. Peptide-modified surfaces for enzyme immobilization. PLoS One 2011, 6, e18692. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, A.A.; Freitas, L.; de Carvalho, A.K.; de Oliveira, P.C.; de Castro, H.F. Immobilization of a commercial lipase from Penicillium camembertii (lipase G) by different strategies. Enzyme Res. 2011, 2011, 967239:1–967239:8. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes-Blackburn, D.; Jorquera, M.; Gianfreda, L.; Rao, M.; Greiner, R.; Garrido, E.; de la Luz Mora, M. Activity stabilization of Aspergillus niger and Escherichia coli phytases immobilized on allophanic synthetic compounds and montmorillonite nanoclays. Bioresour. Technol 2011, 102, 9360–9367. [Google Scholar]

- Madadlou, A.; Iacopino, D.; Sheehan, D.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Mousavi, M.E. Enhanced thermal and ultrasonic stability of a fungal protease encapsulated within biomimetically generated silicate nanospheres. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1800, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Nie, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, H. Immobilization of modified papain with anhydride groups on activated cotton fabric. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 2010, 160, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Tananchai, P.; Chisti, Y. Stabilization of invertase by molecular engineering. Biotechnol. Prog 2010, 26, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kikani, B.A.; Pandey, S.; Singh, S.P. Immobilization of the α-amylase of Bacillus amyloliquifaciens TSWK1–1 for the improved biocatalytic properties and solvent tolerance. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, N.; Govardhan, C.P.; Lalonde, J.J.; Persichetti, R.A.; Wang, Y.F.; Margolin, A.L. Cross-linked enzyme crystals as highly active catalysts in organic solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 5494–5495. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, R.A. Enzyme immobilization: The quest for optimum performance. Adv. Synth. Catal 2007, 349, 1289–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Bommarius, A.S.; Karau, A. Deactivation of formate dehydrogenase (FDH) in solution and at gas-liquid interfaces. Biotechnol. Prog 2005, 21, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Caussette, M.; Gaunand, A.; Planche, H.; Monsan, P.; Lindet, B. Inactivation of enzymes by inert gas bubbling: A kinetic study. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1998, 864, 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Orsat, B.; Drtina, G.J.; Williams, M.G.; Klibanov, A.M. Effect of support material and enzyme pretreatment on enantioselectivity of immobilized subtilisin in organic solvents. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1994, 44, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, A.I.; Malavé, A.J.; Felby, C.; Griebenow, K. Improved activity and stability of an immobilized recombinant laccase in organic solvents. Biotechnol. Lett 2000, 22, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Prodanovic, R.M.; Milosavic, N.B.; Jovanovic, S.M.; Velickovic, T.C.; Vujcic, Z.M.; Jankov, R.M. Stabilization of α-glucosidase in organic solvents by immobilization on macroporous poly(GMA-co-EGDMA) with different surface characteristics. J. Serb. Chem. Soc 2006, 71, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Y.S.; Ibrahim, C.O. Some characteristics of amberlite XAD-7-adsorbed lipase from Pseudomonas sp. AK. Malays. J. Microbiol 2005, 1, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzell, J.D. Commercial scale biocatalysis: Myths and realities. Bioorg. Med. Chem 1999, 7, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Takac, S.; Bakkal, M. Impressive effect of immobilization conditions on the catalytic activity and enantioselectivity of Candida rugosa lipase toward S-Naproxen production. Process Biochem 2007, 42, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz, M.T.; Zonta, A.; Schimossek, K.; Jaeger, K.E.; Liebeton, K. Creation of enantioselective biocatalysts for organic chemistry by in vitro evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1997, 36, 2830–2832. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Mateo, C.; Ortiz, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Modulation of the enantioselectivity of lipases via controlled immobilization and medium engineering: Hydrolytic resolution of mandelic acid esters. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2002, 31, 775–783. [Google Scholar]

- Nishio, T.; Hayashi, R. Digestion of protein substrates by subtilisin: Immobilization changes the pattern of products. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1984, 229, 304–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hernaiz, M.J.; Crout, D.H.G. A highly selective synthesis of N-acetyllactosamine catalyzed by immobilised β-galactosidase from Bacillus circulans. J. Mol. Catal. B 2000, 10, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Boundy, J.A.; Smiley, K.L.; Swanson, C.L.; Hofreiter, B.T. Exoenzymic activity of α-amylase immobilized on a phenol-formaldehyde resin. Carbohydr. Res 1976, 48, 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Linko, Y.Y.; Saarinen, P.; Linko, M. Starch conversion by soluble and immobilized α-amylase. Biotechnol. Bioeng 1975, 17, 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rotticci, D.; Norin, T.; Hult, K. Mass transport limitations reduce the effective stereospecificity in enzyme-catalyzed kinetic resolution. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 1373–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Ogino, S. Formation of the fructose-rich polymer by water-insoluble dextransucrease and presence of glycogen valuelowering factor. Agric. Biol. Chem 1970, 34, 1268–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M.; Segura, R.L.; Mateo, C.; Terreni, M.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Synthesis of enantiomerically pure glycidol via a fully enantioselective lipase-catalyzed resolution. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2005, 16, 869–874. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M.; Segura, R.L.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Enzymatic resolution of (±)-glycidyl butyrate in aqueous media. Strong modulation of the properties of the lipase from Rhizopus oryzae via immobilization techniques. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2004, 15, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M.; Fernández-Lorente, G.; Rúa, M.L.; Guisún, J.M.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Evaluation of the lipase from Bacillus thermocatenulatus as an enantioselective biocatalyst. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2003, 14, 3679–3687. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M.; Muáoz, G.; Fernádez-Lorente, G.; Mateo, C.; Fuentes, M.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Modulation of Mucor miehei lipase properties via directed immobilization on different hetero-functional epoxy resins: Hydrolytic resolution of (R,S)-2-butyroyl-2-phenylacetic acid. J. Mol. Catal. B 2003, 21, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, J.M.; Segura, R.L.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisán, J.M. Glutaraldehyde modification of lipases adsorbed on aminated supports: A simple way to improve their behaviour as enantioselective biocatalyst. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2007, 40, 704–707. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Z.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Palomo, J.M.; Guisan, J.M. Novozym 435 displays very different selectivity compared to lipase from Candida antarctica B adsorbed on other hydrophobic supports. J. Mol. Catal. B 2009, 57, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, O.; Erdemir, S.; Uyanik, A.; Yilmaz, M. Enantioselective hydrolysis of (R/S)-Naproxen methyl ester with sol-gel encapsulated lipase in presence of calix[n]arene derivatives. Appl. Catal. A 2009, 369, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.Y.; Tsai, S.W.; Chen, T.L. Improvements of enzyme activity and enantioselectivity via combined substrate engineering and covalent immobilization. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2008, 101, 460–469. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, J.; Halling, P.J.; Moore, B.D. Practical route to high activity enzyme preparations for synthesis in organic media. Chem. Commun. 1998, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, A.; Maragni, P.; Bismara, C.; Tamburini, B. Enzymatic method of preparation of opticallly active trans-2-amtno cyclohexanol derivatives. Synth. Commun 1999, 29, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, C.; Monti, R.; Pessela, B.C.C.; Fuentes, M.; Torres, R.; Guisán, J.M.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Immobilization of lactase from Kluyveromyces lactis greatly reduces the inhibition promoted by glucose. Full hydrolysis of lactose in milk. Biotechnol. Prog 2004, 20, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Pessela, B.C.C.; Mateo, C.; Fuentes, M.; Vian, A.; Garcia, J.L.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. The immobilization of a thermophilic β-galactosidase on Sepabeads supports decreases product inhibition: Complete hydrolysis of lactose in dairy products. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2003, 33, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Brazeau, B.J.; de Souza, M.L.; Gort, S.J.; Hicks, P.M.; Kollmann, S.R.; Laplaza, J.M.; McFarlan, S.C.; Sanchez-Riera, F.A.; Solheid, C. Polypeptides and Biosynthetic Pathways for the Production of Stereoisomers of Monatin and Their Precursors. U.S. Patent 20080020434, 24 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.J.; Jung, S.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, Y.G.; Nam, K.C.; Lee, H.J.; Bae, H.J. Co-immobilization of three cellulases on Au-doped magnetic silica nanoparticles for the degradation of cellulose. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 886–888. [Google Scholar]

- Betancor, L.; Berne, C.; Luckarift, H.R.; Spain, J.C. Coimmobilization of a redox enzyme and a cofactor regeneration system. Chem. Commun. 2006, 3640–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Clair, N.; Wang, Y.F.; Margolin, A.L. Cofactor-bound cross-linked enzyme crystals (CLEC) of alcohol dehydrogenase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2000, 39, 380–383. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, S.F.M.; Nallani, M.; Cornelissen, J.J.L.M.; Nolte, R.J.M.; van Hest, J.C.M. A three-enzyme cascade reaction through positional assembly of enzymes in a polymersome nanoreactor. Chem. Eur. J 2009, 15, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, D.; Jordaan, J.; Simpson, C.; Chetty, A.; Arumugam, C.; Moolman, F.S. Spherezymes: A novel structured self-immobilisation enzyme technology. BMC Biotechnol 2008, 8, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Pundir, C.S.; Chauhan, N. Coimmobilization of detergent enzymes onto a plastic bucket and brush for their application in cloth washing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2012, 51, 3556–3563. [Google Scholar]

- Minakshi; Pundir, C.S. Co-immobilization of lipase, glycerol kinase, glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase and peroxidase on to aryl amine glass beads affixed on plastic strip for determination of triglycerides in serum. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 45, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Haam, S.; Jang, K.; Ahn, I.S.; Kim, W.S. Immobilization of starch-converting enzymes on surface-modified carriers using single and co-immobilized systems: Properties and application to starch hydrolysis. Process Biochem 2005, 40, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, G.; Velarde-Ortiz, R.; Minchow, K.; Barrero, A.; Loscertales, I.G. A method for making inorganic and hybrid (organic/inorganic) fibers and vesicles with diameters in the submicrometer and micrometer range via sol-gel chemistry and electrically forced liquid jets. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 1154–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Grate, J.W.; Wang, P. Nanostructures for enzyme stabilization. Chem. Eng. Sci 2006, 61, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Grate, J.W.; Wang, P. Nanobiocatalysis and its potential applications. Trends Biotechnol 2008, 26, 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, E.T.; Tatavarty, R.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. Shape reformable polymeric nanofibers entrapped with QDs as a scaffold for enzyme stabilization. J. Mater. Chem 2011, 21, 5215–5218. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Jin, L.H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, S.O.; Na, H.B.; Hyeon, T.; Koo, Y.M.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.H. β-glucosidase coating on polymer nanofibers for improved cellulosic ethanol production. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng 2010, 33, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.; Ponvel, K.M.; Ahn, I.; Lee, C. Synthesis of magnetic/silica nanoparticles with a core of magnetic clusters and their application for the immobilization of His-tagged enzymes. J. Mater. Chem 2010, 20, 1511–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Herricks, T.E.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Li, D. Direct fabrication of enzyme-carrying polymer nanofibers by electrospinning. J. Mater. Chem 2005, 15, 3241–3245. [Google Scholar]

- Martinek, K.; Mozhaev, V.V. Practice importance of enzyme stability. 2. Increase of enzyme stability by immobilization and treatment with low-molecularweight reagents. Pure Appl. Chem 1991, 63, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar]

- Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C.O. Microwave-assisted synthesis in water as solvent. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 2563–2591. [Google Scholar]

- Galinada, W.A.; Guiochon, G. Influence of microwave irradiation on the intraparticle diffusion of an insulin variant in reversed-phase liquid chromatography under linear conditions. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1163, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, R.S.; Saini, R.K. Microwave-assisted reduction of carbonyl compounds in solid state using sodium borohydride supported on alumina. Tetrahedron Lett 1997, 38, 4337–4338. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, R.S.; Dahiya, R.; Saini, R.K. Lodobenzene diacetate on alumina: Rapid oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds in solventless system using microwaves. Tetrahedron Lett 1997, 38, 7029–7032. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, C.; Du, Z.; Shen, S. An efficient immobilizing technique of penicillin acylase with combining mesocellular silica foams support and p-benzoquinone cross linker. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng 2008, 31, 509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhou, C.; Du, Z.; Zhu, S.; Shen, S.; Ouyang, P. Improving enzyme immobilization in mesocellular siliceous foams by microwave irradiation. J. Biosci. Bioeng 2008, 106, 286–291. [Google Scholar]

- Nahar, P.; Bora, U. Microwave-mediated rapid immobilization of enzymes onto an activated surface through covalent bonding. Anal. Biochem 2004, 328, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, A.; Nahar, P. Photochemical immobilization of proteins on microwave-synthesized photoreactive polymers. Anal. Biochem 2004, 327, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Nahar, P. Sunlight-induced covalent immobilization of proteins. Talanta 2007, 71, 1438–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y.; Tsuruda, Y.; Nishi, M.; Kamiya, N.; Goto, M. Exploring enzymatic catalysis at a solid surface: A case study with transglutaminase-mediated protein immobilization. Org. Biomol. Chem 2007, 5, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L.S.; Thirlway, J.; Micklefield, J. Direct site-selective covalent protein immobilization catalyzed by a phosphopantetheinyl transferase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 12456–12464. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, J.M.; Hidalgo, A.; Sanchez-Ruiloba, L.; Berenguer, J.; Guisan, J.M.; Lopez-Gallego, F. Modulation of the distribution of small proteins within porous matrixes by smart-control of the immobilization rate. J. Biotechnol 2011, 155, 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Martín, J.; de las Rivas, B.; Muñoz, R.; Guisán, J.M.; López-Gallego, F. Rational co-immobilization of bi-enzyme cascades on porous supports and their applications in bio-redox reactions with in situ recycling of soluble cofactors. ChemCatChem 2012, 4, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, S.; Kapoor, M.; Gupta, M.N. Preparation and characterization of combi-CLEAs catalyzing multiple non-cascade reactions. J. Mol. Catal. B 2007, 44, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A.C.; Church, G.M. Synthetic biology projects in vitro. Genome Res 2007, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, J.; van Oudenaarden, A. Synthetic biology: The yin and yang of nature. Nature 2009, 457, 271–272. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, C.A.; de las Rivas, B.; Grazu, V.; Montes, T.; Guisan, J.M.; Lopez-Gallego, F. Glyoxyl-disulfide agarose: A tailor-made support for site-directed rigidification of proteins. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1800–1809. [Google Scholar]

| Enzyme | Organism | Improved property | Method | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydantoinase | Arthrobacter sp. | Enantioselective hydantoinase and 5-fold more productivity | Saturation mutagenesis, screening | Production of l-Met (l-amino acids) | [7] |

| Cyclodextrin glucanotransferase | Bacillus stearothermophilus ET1 | Modulation of cyclizing activity and thermostability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Bread industry | [8] |

| Lipase B | Candida antarctica | 20-fold increase in half-life at 70 °C | epPCR | Resolution and desymmetrization of compound | [9] |

| Tagatose-1,6-Bisphosphate aldolase | E. coli | 80-fold improvement in kcat/Km and 100-fold change in stereospecificity | DNA shuffling and screening | Efficient syntheses of complex stereoisomeric products | [10] |

| Xylose isomerase | Thermotoga neapolitana | High activity on glucose at low temperature and low pH | Random Mutagenesis and screening | Used in preparation of high fructose syrup | [11] |

| Amylosucrase | Neisseria polysaccharea | 5-fold increased activity | Random mutagenesis, gene shuffling, and directed evolution | Synthesis or the modification of polysaccharides | [12] |

| Galactose oxidase | F. graminearum | 3.4–4.4 fold greater Vmax/Km and increased specificity | epPCR and screening | Derivatization of guar gum | [13] |

| Fructose bisphosphate aldolase | E. coli | Increased thermostablity and stability to treatment with organic solvent | DNA shuffling | Use in organic synthesis | [14] |

| 1,3-1,4-α-d-glucanase | Fibrobacter succinogenes | 3–4-fold increase in the turnover rate (k) | PCR-based gene truncation | Beer industry | [15] |

| Lipase | P. aeruginosa | 2-fold increase in amidase activity | Random mutagenesis and screening | Understanding lipase inability to hydrolyze amides | [16] |

| Protease BYA | Bacillus sp. Y | Specific activity1.5-fold higher | Site-directed mutagenesis | Detergents products | [17] |

| p-Hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase | Pseudomonas fluorescens NBRC 14160 | Activity, reaction specificity, and thermal stability | Combinatorial mutagenesis | Degrading various aromatic compounds in the environment | [18] |

| Endo-1,4-β-xylanase II | Trichoderma reesei | Increased alkali stability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Sulfate pulp bleaching | [19] |

| Xylose isomerase | Thermotoga neapolitana | 2.3-fold increases in catalytic efficiency | Random mutagenesis | Production of high fructose corn syrup | [11] |

| α-Amylase | Bacillus sp. TS-25 | 10 °C enhancement in thermal stability | Directed evolution | Baking industry | [20] |

| Xylanase | Tm improved by 25 °C | Gene site-saturation mutagenesis | Degradation of hemicellulose | [21] | |

| Fructosyl peptide oxidase | Coniochaeta sp | 79.8-fold enhanced thermostability | Directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis | Clinical diagnosis | [22] |

| Endo-β-1,4-xylanase | Bacillus subtilis | Acid stability | Rational protein engineering | Degradation of hemicellulose | [23] |

| Subtilase | Bacillus sp. | 6-fold increase in caseinolytic activity at 15–25 °C | Directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis | Detergent additives and food processing | [24] |

| CotA laccase | B. subtilis | 120-fold more specific for ABTS | Directed evolution | Catalyze oxidation of polyphenols | [25] |

| Pyranose 2-oxidase | Trametes multicolor | Altered substrate selectivity for d-galactose, d-glucose | Semi-rational enzyme engineering approach | Food industry | [26] |

| Xylanase XT6 | Geobacillus stearothermophilus | 52-fold enhancement in thermostability; increased catalytic efficiency | Directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis | Degradation of hemicellulose | [27] |

| Lipase | Bacillus pumilus | Thermostability and 4-fold increase in kcat | Site-directed mutagenesis | Chemical, food, leather and detergent industries | [28] |

| Bgl-licMB | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (Bgl) and Clostridium thermocellum (licMB) | 2.7 and 20-fold higher kcat/Km than that of the parental Bgl and licMB, respectively | Splicing-by-overlap extension | Brewing and animal-feed industries | [29] |

| β-agarase AgaA | Zobellia galactanivorans | Catalytic activity and thermostability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Production of functional neo-agarooligosaccharides | [30] |

| Prolidase | Pyrococcus horikoshii | Thermostability | Random mutagenesis | Detoxification of organophosphorus nerve agents | [31] |

| Lipases | Geobacillus sp. NTU 03 | 79.4-fold increment in activity; 6.3–79-fold enhanced thermostability | Error-prone PCR and site-saturation mutagenesis | Transesterification | [32] |

| Xylanase | Hypocrea jecorina | Thermostability | Look-through mutagenesis (LTMTM) and combinatorial beneficial mutagenesis (CBMTM) | Degradation of hemicellulose | [33] |

| Amylase | Bacillus sp. US149 | Thermostability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Bread industry | [34] |

| Cholesterol oxidase | Brevibacterium sp. | Thermostability and enzymatic activity | Site-directed mutagenesis | Detection and conversion of cholesterol | [35] |

| Lipase B | Candida antarctica | Enhancement of thermostability | Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and site-directed mutagenesis | Detergent industries | [36] |

| Laccase | Bacillus HR03 | 3-fold improved kcat and thermostability | Directed mutagenesis | Catalyze oxidation of polyphenols, and polyamines | [37] |

| d-psicose 3-epimerase | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Thermostability | Random and site-directed mutagenesis | Industrial producer of d-psicose | [38] |

| 1,3-1,4-β-d-glucanase | Fibrobacter succinogenes | Thermostability and specific activity | Rational mutagenesis | Widely used as a feed additive | [39] |

| α-Amylase | Bacillus licheniformis | Acid stability | Direct evolution | Starch hydrolysis | [40] |

| Alkaline amylase | Alkalimonas amylolytica | Oxidative stability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Detergent and textile industries | [41] |

| Endoglucanase | Thermoascus aurantiacus | 4-fold increase in kcat and 2.5-fold improvement in hydrolytic activity on cellulosic substrates | Site-directed mutagenesis | Bioethanol production | [42] |

| d-glucose 1-dehydrogenase isozymes | Bacillus megaterium | Substrate specificity | Site-directed mutagenesis | Measurements of blood glucose level | [43] |

| Glycerol dehydratase | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2-fold pH stability; enhanced specific activity | Rational design | Synthesis of 1,3-Propanediol | [44] |

| Cyclodextrin Glucanotransferase | Bacillus sp. G1 | Enhancement of thermostability | Rational mutagenesis | Starch is converted into cyclodextrins | [45] |

| Cellobiose phosphorylase | Clostridium thermocellum | Enhancement of thermostability | Combined rational and random approaches | Phosphorolysis of cellobiose | [46] |

| Superoxide dismutase | Potentilla atrosanguinea | Thermostability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Scavenging of O2− | [47] |

| Endoglucanase Cel8A | Clostridium thermocellum | Thermostability | Consensus-guided mutagenesis | Conversion of cellulosic biomass to biofuels | [48] |

| Endo β-glucanase EgI499 | Bacillus subtilis JA18 | Increase in half life from 10 to 29 mins at 65 °C | Deletion of C-terminal region | Animal feed production | [49] |

| Pyranose 2-oxidase | Trametes multicolor | Increase half life from 7.7 min to 10 h (at 60 °C) | Designed triple mutant | Food industry | [50] |

| Xylanase XT6 | Geobacillus stearothermophilus | 52× increase in thermal stability, kopt increase by 10 °C, catalytic efficiency increase by 90% | Directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis | Biobleaching | [27] |

| Tyrosine phenol-lyase | Symbiobacterium toebi | Improved thermal stability and activity (Increase in Tm up to 11.2 °C) | Directed evolution (random mutagenesis, reassembly and activity screening) | Industrial production of l-tyrosine and its derivatives | [51] |

| Phytase | Penicilium sp. | Increased thermal stability | Random mutation and selection | Feed additives | [52] |

| l-Asparaginase | Erwinia carotovora | Increase in half-life from 2.7 to 159.7 h | In vitro directed evolution | Therapeutic agent | [53] |

| Endoglucanase CelA | Clostridium thermocellum | 10-fold increase in half-life of inactivation at 86 °C | Saturation mutagenesis | Bioconversion of cellulosic biomass | [54] |

| β-glucosidase BglC | Thermobifida fusca | Increase in half-life from 12 to 1244 min | Family shuffling, site saturation, and site-directed mutagenesis | Bioconversion of cellulosic biomass | [55] |

| Phospholipase D | Streptomyces | Improved thermal stability and activity | Semi-rational, site-specific saturation mutagenesis | Phosphatidylinositol synthesis | [56] |

| β-glucosidase | Trichoderma reesei | Enhanced kcat/Km and kcat values by 5.3- and 6.9-fold | Site-directed mutagenesis | Hydrolysis of cellobiose and cellodextrins | [57] |

| Lipases | 144-fold enhanced thermostability | Error prone PCR | Synthesis and hydrolysis of long chain fatty acids | [58] | |

| Laccase | Pycnoporus cinnabarinus | 8000-fold increase in kcat/Km | Directed evolution and semi-rational engineering | Lignocellulose biorefineries, organic synthesis, and bioelectrocatalysis | [59] |

| Feruloyl esterase A | Aspergillus niger | Increase in half-life from 15 to >4000 min | Random and site-directed mutagenesis | Degradation of lignocellulose | [60] |

| Enzyme | Applications | Kinetic parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Chymotrypsin | Proteolysis (cleave Peptide amide bonds) | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 31.7 μM, kcat = 20.0 s−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 47.8 μM, kcat = 17.8 s−1 | [141] |

| β-glucosidase | Lignocellulose hydrolysis | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 10.8 mM, Vmax = 2430 μmol·min−1·mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 1.1 mM, Vmax = 296 μmol·min−1·mg−1 | [142] |

| Glucose oxidase | Estimation of glucose level up to 300 mg·mL−1 | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 3.74 mM, soluble enzyme = 5.85 mM | [143] |

| Diastase | Starch hydrolysis | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 8414 mM, Vmax = 4.92 μmol min−1 mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 10,176 mM, Vmax = 2.71 μmol min−1 mg−1 | [144] |

| β-galactosidase | GOS synthesis | Immobilized enzyme: k1 = 1.41 h−1; soluble enzyme: k1 = 1.16 h−1 | [145] |

| Keratinase | Synthesis of keratin | Immobilized enzyme: specific activity = 129.0 U·mg−1; soluble enzyme: specific activity = 37 U·mg−1 | [146] |

| Horseradish peroxidase | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 0.8 mM, Vmax = 0.72 μmol min−1 mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 0.43 mM, Vmax = 0.35 μmol min−1 mg−1 | [147] | |

| Glucose oxidase | Estimation of glucose level | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 2.7 mM, Vmax = 28.6 U·μg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 9 mM, Vmax = 6.2 μmol·min−1 mg−1 | [148] |

| β-1,4-glucosidase (Agaricus arvensis) | Lignocellulose hydrolysis | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 3.8 mM, Vmax = 3,347 μmol min−1 mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 2.5 mM, Vmax = 3,028 μmol min−1 mg−1 | [149] |

| l-arabinose isomerase (B. licheniformis) | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 352 mM, Vmax = 326 μmol min−1 mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 369 mM, Vmax = 232 μmol min−1 mg−1 | [150] | |

| Diastase α-amylase | Hydrolyzing soluble starch | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 10.3 mg/mL; Vmax = 4.36 μmol min−1 mg−1 mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 8.85 mg mL−1; Vmax = 2.81 μmol·min−1·mg−1 | [151] |

| Cellobiase | Bioethanol production | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 0.30 mM, Vmax = 6.77 μM min−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 2.48 mM, Vmax = 2.38 μM min−1 | [152] |

| Laccase | Bioremediation of environmental pollutants | Immobilized enzyme: Km (10−2 mM) = 10.7, Vmax (10−2 mM min−1) = 14.0; soluble enzyme: Km (10−2 mM) = 5.69, Vmax (10−2 mM min−1) = 7.7 | [153] |

| Keratinase | Synthesis of keratin | Immobilized enzyme: specific activity = 129 U mg−1; soluble enzyme: specific activity = 37 U mg−1 | [146] |

| Raw starch digesting amylases | Starch hydrolysis | Immobilized enzyme: Km (10−1) = 3.8 mg mL−1, Vmax = 27.3 U·mg−1; soluble enzyme: Km (10−1) = 3.5 mg mL−1, Vmax = 23.8 U·mg−1 | [154] |

| Aldolase | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 0.10 mM; kcat/Km = 584 min−1·mM−1, soluble enzyme Km = 0.12 mM; kcat/Km = 540 min−1·mM−1 | [155] | |

| α-galactosidase (Aspergillus terreusGR) | Animal feed | Immobilized enzyme: Km =1.40 mM, Vmax =20.16 U mL−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 4.2 mM, Vmax =16.33 U·mL−1 | [156] |

| Laccase | Textile wastewater treatment | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 0.0717 mM, Vmax = 0.247 mM·min−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 0.0044 mM, Vmax = 0.024 mM·min−1 | [157] |

| Papain | Food, pharmaceutical, leather, cosmetic, and textile industries | Immobilized enzyme: Km = 0.308 × 105 g·mL−1; Vmax = 5.4 g mL−1 s−1; soluble enzyme: Km = 0.236 × 105 g·mL−1; Vmax = 4.08 g·mL−1·s−1 | [158] |

| Enzyme | Recovered activity (%) | Stabilization factor a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipase (C. rugosa) | 50 | 150 a | [192] |

| Penicillin G acylase (E. coli) | 70 | 8000 a | [193] |

| Chymotrypsin | 70 | 60,000 a | [194] |

| Penicillin G acylase (K. citrophila) | 70 | 7000 a | [195] |

| Esterase (B. stearothermophilus) | 70 | 1000 a | [178] |

| Thermolysin (B. thermoproteolyticus) | 100 | 100 a | [191] |

| Cholesterol oxidase | nd | 2.5 (50 °C) | [196] |

| Alcalase | 54 | 500 | [197] |

| Urokinase | 80 | 10 | [198] |

| α-Amylase (B. licheniformis) | nd | 2 (70 °C) | [199] |

| Invertase | nd | 2 (70 °C) | [200] |

| Dextransucrase (L. mesenteriodes) | nd | 40 (30 °C) | [201] |

| Formate dehydrogenase (Pseudomonas sp. 101) | 50 | >5000 a | [188] |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase (H. Liver) | 90 | >3000 | [202] |

| Cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase (B. circulans) | 70 | >100 | [203] |

| Formate dehydrogenase (C. boidini) | 15 | 150 a | [204] |

| Laccase (Rhus vernicifera) | 80 | 6.4 (65 °C) | [205] |

| Xylitol dehydrogenase (Rhizobium etli) | 92 | 2.2 (60 °C) | [206] |

| Laccase (Trametes versicolor) | 69 | 2.5 (45 °C) | [207] |

| β-1,4-glucosidase (Agaricus arvensis) | 158 | 288 (65 °C) | [149] |

| Cellulase (Trichoderma viride) | nd | 2 (55 °C) | [208] |

| β-Galactosidase | nd | 17 (55 °C) | [209] |

| Lipase G (Penicillium camembertii) | nd | 1.7 (40 °C) | [210] |

| Phytases (Aspergillus niger) | 66 | 7 (60 °C) | [211] |

| Phytases (Escherichia coli) | 74 | 9.7 (60 °C) | [211] |

| L-arabinose isomerase (Bacillus licheniformis) | 145 | 137.5 (50 °C) | [150] |

| Protease (Aspergillus oryzea) | 85 | 3.5 (70 °C) | [212] |

| Papain | 40 | 4.2 (70 °C) | [213] |

| Cellobiase | 284 | 1.2 (60 °C) | [152] |

| Invertase | NR | 3.5 (55 °C) | [214] |

| α-Amylase (Bacillus amyloliquifaciens TSWK1-1) | 91 | 3.75 (60 °C) | [215] |

| α-Galactosidase (Aspergillus terreusGR) | 74 | 3.5 (65 °C) | [156] |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, R.K.; Tiwari, M.K.; Singh, R.; Lee, J.-K. From Protein Engineering to Immobilization: Promising Strategies for the Upgrade of Industrial Enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 1232-1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011232

Singh RK, Tiwari MK, Singh R, Lee J-K. From Protein Engineering to Immobilization: Promising Strategies for the Upgrade of Industrial Enzymes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(1):1232-1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011232

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Raushan Kumar, Manish Kumar Tiwari, Ranjitha Singh, and Jung-Kul Lee. 2013. "From Protein Engineering to Immobilization: Promising Strategies for the Upgrade of Industrial Enzymes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 1: 1232-1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011232