Design and Synthesis of Binding Growth Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

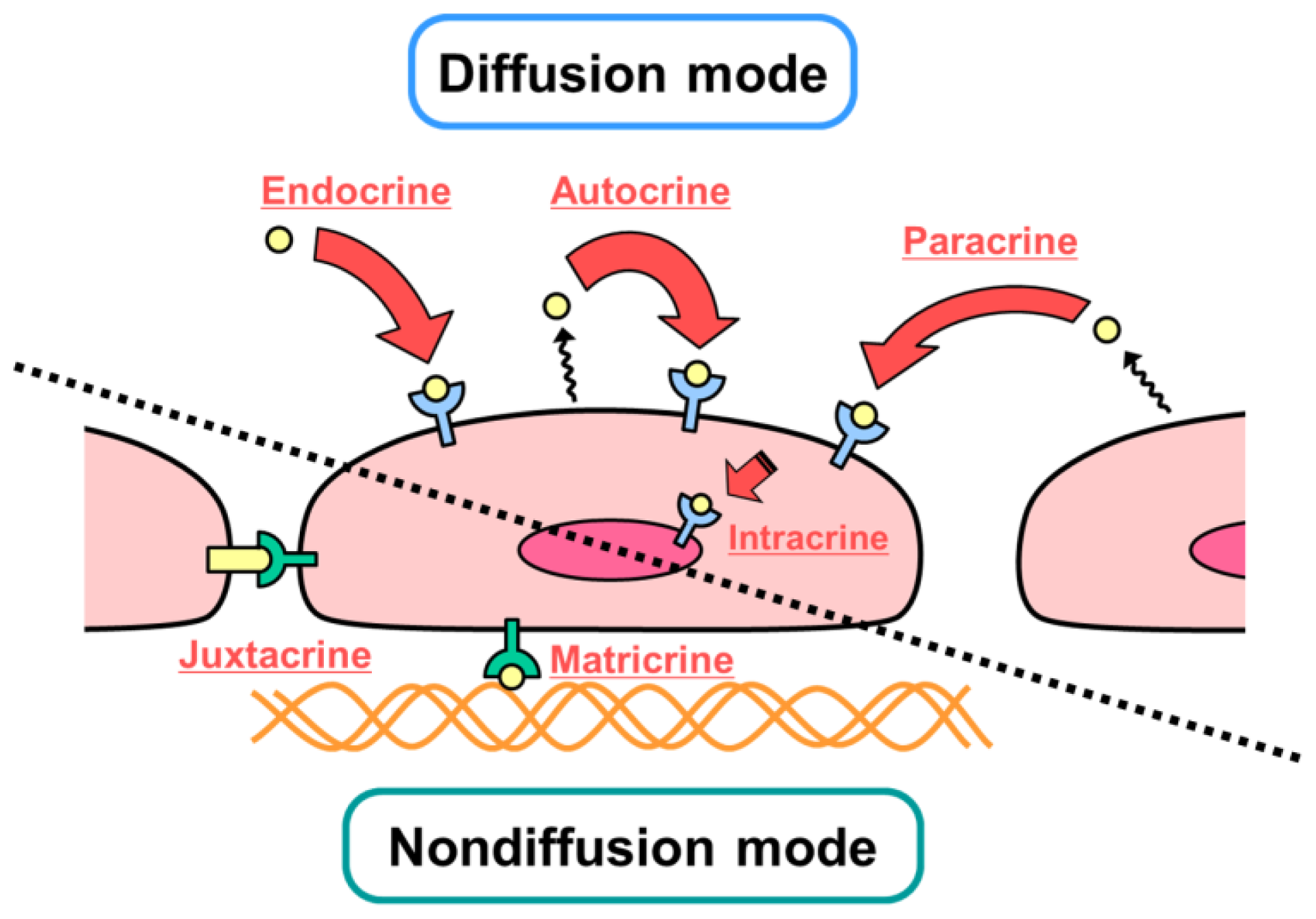

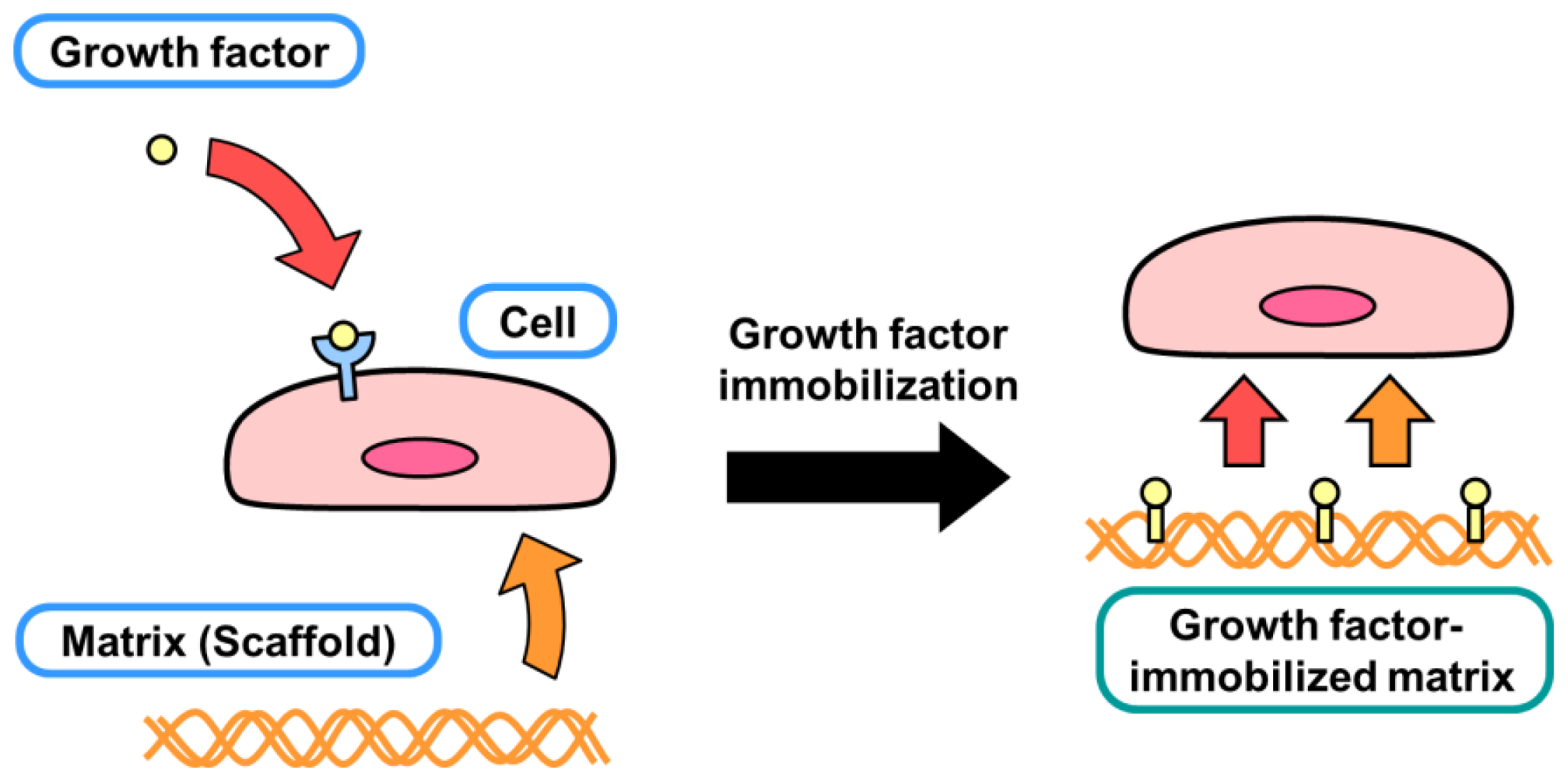

2. Diffusible and Nondiffusible Actions of Growth Factors

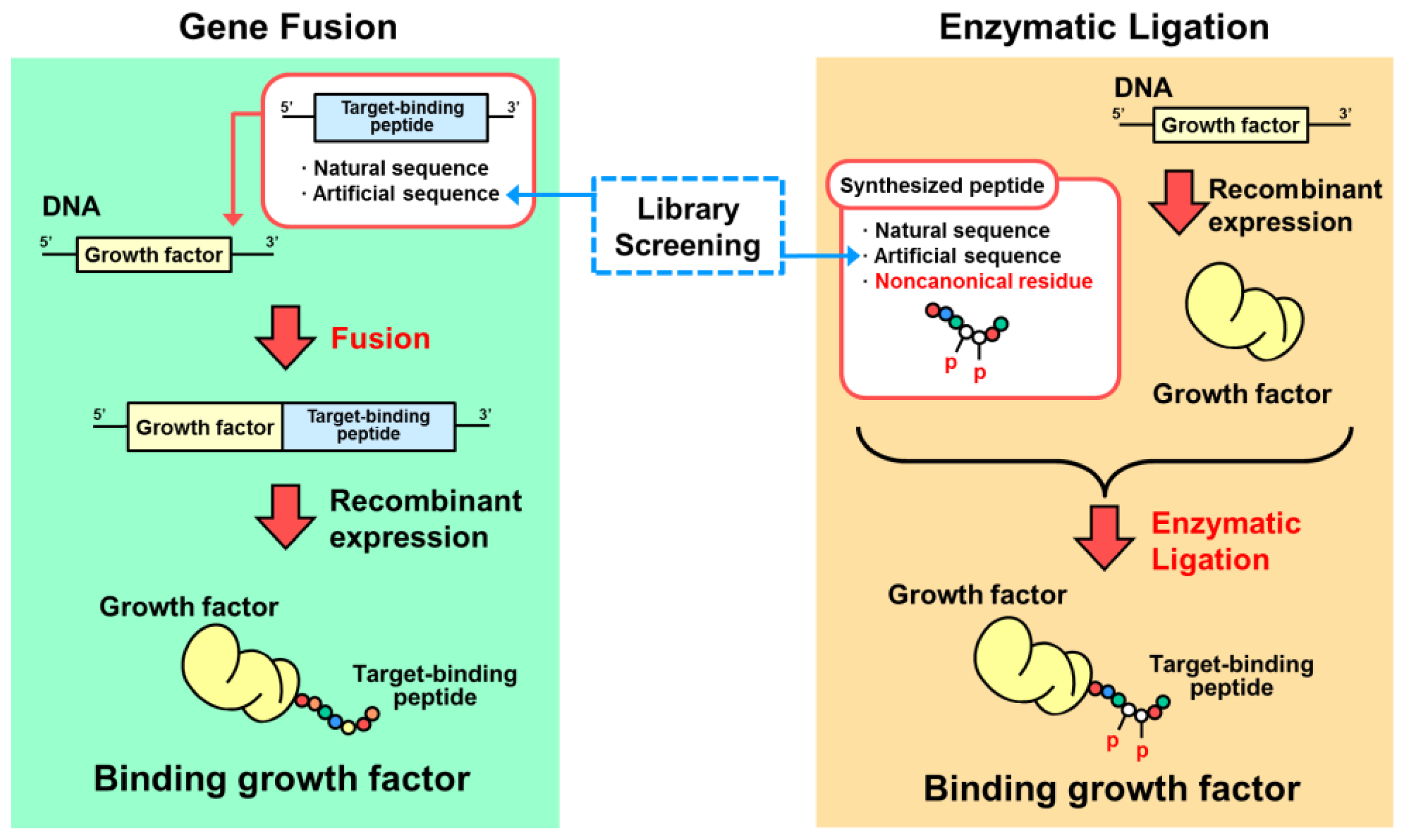

3. Designs Based on Genetic Fusion

3.1. Collagen-Binding Growth Factors

3.2. Fibrin-Binding Growth Factors

3.3. Cell-Binding Fusion Proteins

3.4. Organic Material-Binding Growth Factors

3.5. Titanium-Binding Growth Factors

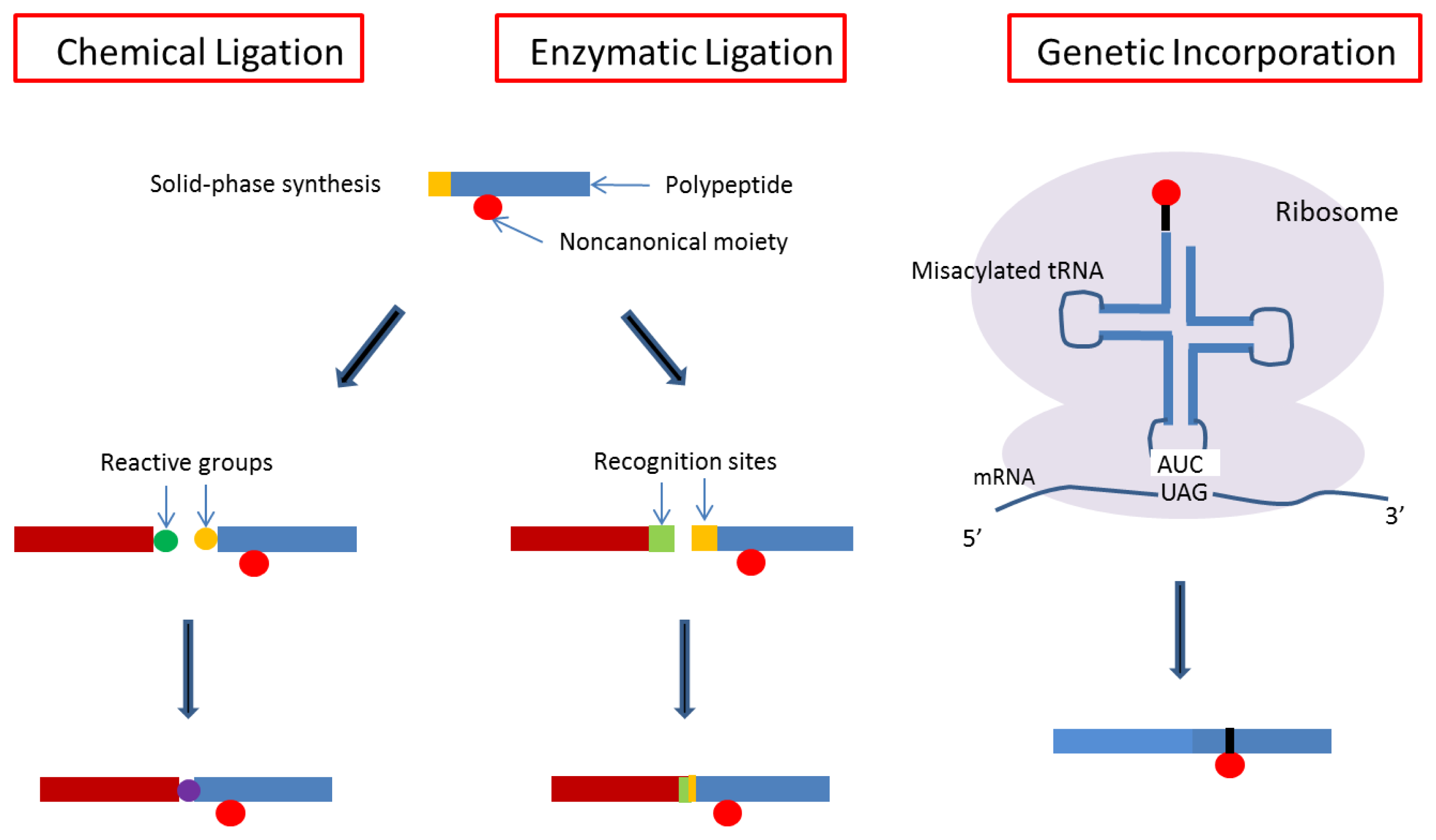

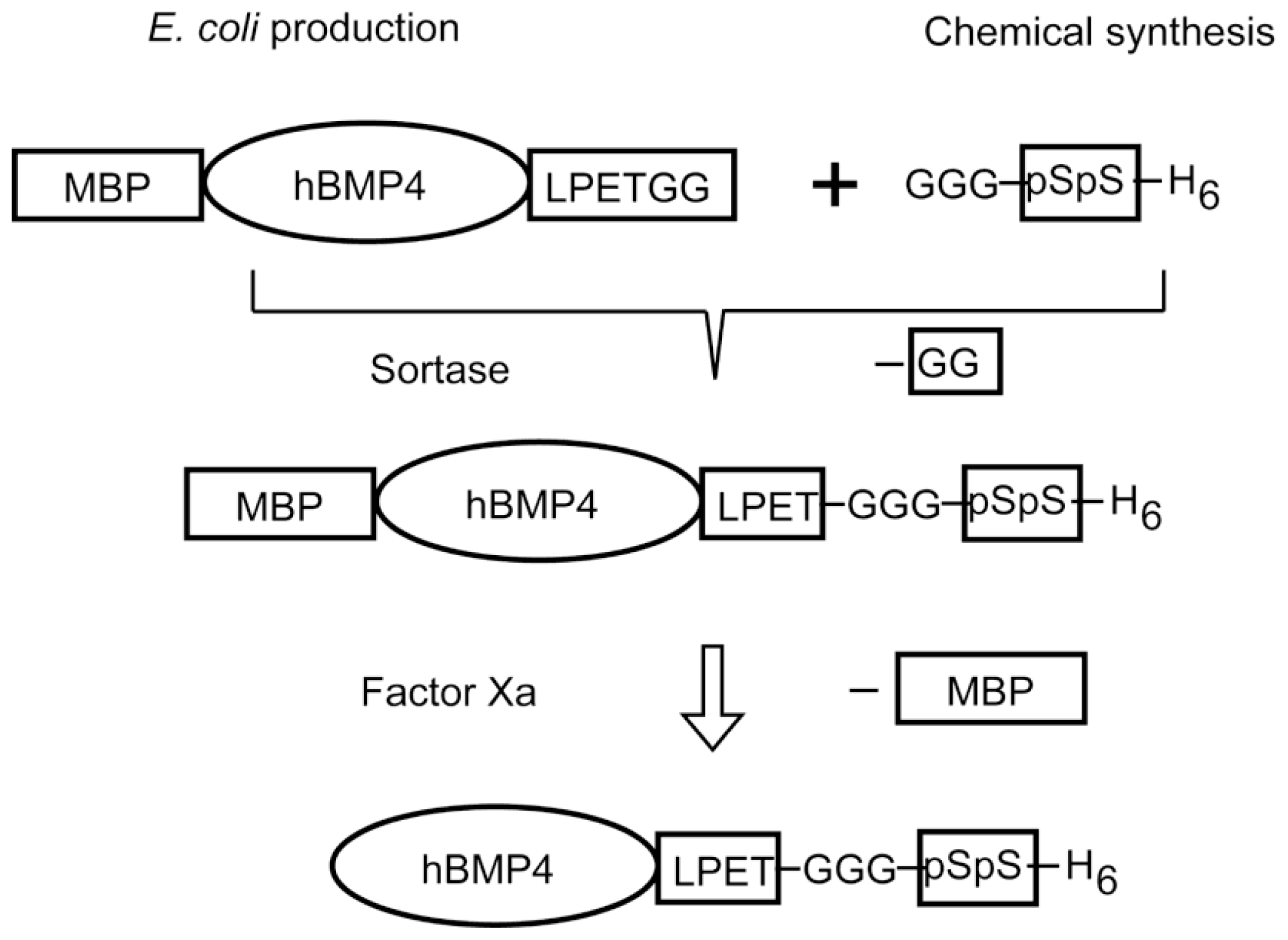

4. Designs Based on Peptide Ligation

5. Application of Engineered Binding Growth Factors

5.1. Wound Healing

5.2. Repair of Cardiovascular Tissues by Implants

5.3. Nerve Regeneration

5.4. Bone Regeneration

6. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

- Conflict of Interest StatementThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Werner, S.; Grose, R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol. Rev 2003, 83, 835–870. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, M.J.; Quirk, R.A.; Howdle, S.M.; Shakesheff, K.M. Growth factor release from tissue engineering scaffolds. Pharm. Pharmacol 2001, 53, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Massagué, J.; Pandiella, A. Membrane-anchored growth factors. Ann. Rev. Biochem 1993, 62, 515–541. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, R.; Mekada, E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor: A juxtacrine growth factor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2000, 11, 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, T.; Ito, Y. Artificial Binding Growth Factors. In Handbook of Intelligent Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine; Khang, G., Ed.; Pan Stanford Publishing; Singapore, 2012; pp. 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y. Elaborate synthesis of biological macromolecules. ChemBioChem 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, T.L.; Cheung, D.T.; Wu, L.T.; Yee, A.; Gabriel, S.; Han, B.; Morton, L.; Nimni, M.E.; Hall, F.L. Engineering, expression and renaturation of targeted TGF-beta fusion proteins. Connect. Tissue Res 1996, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Andrades, J.A.; Han, B.; Becerra, J.; Sorgente, N.; Hall, F.L.; Nimni, M.E. A recombinant human TGF-beta1 fusion protein with collagen-binding domain promotes migration, growth, and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal cells. Exp. Cell. Res 1999, 250, 485–498. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, F.L.; Kaiser, A.; Liu, L.; Chen, Z.H.; Hu, J.; Nimni, M.E.; Beart, R.W., Jr; Gordon, E.M. Design, expression, and renaturation of a lesion-targeted recombinant epidermal growth factor-von Willebrand factor fusion protein: Efficacy in an animal model of experimental colitis. Int. J. Mol. Med 2000, 6, 635–643. [Google Scholar]

- Andrades, J.A.; Santamaría, J.A.; Wu, L.T.; Hall, F.L.; Nimni, M.E.; Becerra, J. Production of a recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor with a collagen binding domain. Protoplasma 2001, 218, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Perelman, N.; Tang, B.; Hall, F.; Shors, E.C.; Nimni, M.E. Collagen-targeted BMP3 fusion proteins arrayed on collagen matrices or porous ceramics impregnated with Type I collagen enhance osteogenesis in a rat cranial defect model. J. Orthop. Res 2002, 20, 747–755. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, N.; Matsushita, O.; Yuube, K.; Miyanaka, H.; Okabe, A.; Wada, F. Collagen-binding growth factors: Production and characterization of functional fusion proteins having a collagen-binding domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7018–7023. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, L.P.; Washington, C.; Brey, E.M.; Gassman, A.; Subramanian, A.; Calceterra, J.; Wolf, W.; Hall, C.L.; Velander, W.H.; Burgess, W.H.; et al. Construction and characterization of a thrombin-resistant designer FGF-based collagen binding domain angiogen. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, J. The effect of collagen-targeting platelet-derived growth factor on cellularization and vascularization of collagen scaffolds. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 5708–5714. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, B.; Li, X.; Lin, H.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Han, Q.; Dai, J. Vascularization and cellularization of collagen scaffolds incorporated with two different collagen-targeting human basic fibroblast growth factors. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 82, 630–636. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Lin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dai, J. Activation of demineralized bone matrix by genetically engineered human bone morphogenetic protein-2 with a collagen binding domain derived from von Willebrand factor propolypeptide. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 80, 428–434. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Lin, H.; Chen, B.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, J. Promotion of peripheral nerve growth by collagen scaffolds loaded with collagen-targeting human nerve growth factor-beta. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 83, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Q.; Sun, W.; Lin, H.; Zhao, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, B.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, B.; Dai, J. Linear ordered collagen scaffolds loaded with collagen-binding brain-derived neurotrophic factor improve the recovery of spinal cord injury in rats. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 2927–2935. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, B.; Han, Q.; Sun, W.; Xiao, Z.; Dai, J. Collagen-binding human epidermal growth factor promotes cellularization of collagen scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, L.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W.; Chen, B.; Lin, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, B.; Dai, J. Collagen-targeting vascular endothelial growth factor improves cardiac performance after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2009, 119, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Tang, G.; Hou, X.; Ding, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, P.; Dai, J.; Xu, R. Linear ordered collagen scaffolds loaded with collagen-binding neurotrophin-3 promote axonal regeneration and partial functional recovery after complete spinal cord transection. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T.; Terai, H.; Kitajima, T. Production of a biologically active epidermal growth factor fusion protein with high collagen affinity. J. Biochem 2001, 129, 627–633. [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, T.; Terai, H.; Ito, Y. A fusion protein of hepatocyte growth factor for immobilization to collagen. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T.; Eguchi, M.; Wada, M.; Iwami, Y.; Tono, K.; Iwaguro, H.; Masuda, H.; Tamaki, T.; Asahara, T. Establishment of a functionally active collagen-binding vascular endothelial growth factor fusion protein in situ. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 2006, 26, 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sakiyama-Elbert, S.E.; Panitch, A.; Hubbell, J.A. Development of growth factor fusion proteins for cell-triggered drug delivery. FASEB J 2001, 15, 1300–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Schmoekel, H.G.; Weber, F.E.; Schense, J.C.; Grätz, K.W.; Schawalder, P.; Hubbell, J.A. Bone repair with a form of BMP-2 engineered for incorporation into fibrin cell ingrowth matrices. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2005, 89, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Geer, D.J.; Swartz, D.D.; Andreadis, S.T. Biomimetic delivery of keratinocyte growth factor upon cellular demand for accelerated wound healing in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Pathol 2005, 167, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Zisch, A.H.; Schenk, U.; Schense, J.C.; Sakiyama-Elbert, S.E.; Hubbell, J.A. Covalently conjugated VEGF-fibrin matrices for endothelialization. J. Control. Release 2001, 72, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrbar, M.; Djonov, V.G.; Schnell, C.; Tschanz, S.A.; Martiny-Baron, G.; Schenk, U.; Wood, J.; Burri, P.H.; Hubbell, J.A.; Zisch, A.H. Cell-demanded liberation of VEGF121 from fibrin implants induces local and controlled blood vessel growth. Circ. Res 2004, 94, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Sahni, A.; Francis, C.W. Vascular endothelial growth factor binds to fibrinogen and fibrin and stimulates endothelial cell proliferation. Blood 2000, 96, 3772–3778. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrbar, M.; Zeisberger, S.M.; Raeber, G.P.; Hubbell, J.A.; Schnell, C.; Zisch, A.H. The role of actively released fibrin-conjugated VEGF for VEGF receptor 2 gene activation and the enhancement of angiogenesis. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1720–1729. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Lorentz, K.M.; Yang, L.; Frey, P.; Hubbell, J.A. Engineered insulin-like growth factor-1 for improved smooth muscle regeneration. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 494–503. [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, T.; Sakuragi, M.; Hasuda, H.; Ozu, T.; Ito, Y. A chimeric epidermal growth factor with fibrin affinity promotes repair of injured keratinocyte sheets. Acta Biomater 2009, 5, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar]

- Kawase, Y.; Ohdate, Y.; Shimojo, T.; Taguchi, Y.; Kimizuka, F.; Kato, I. Construction and characterization of a fusion protein with epidermal growth factor and the cell-binding domain of fibronectin. FEBS Lett 1992, 298, 126–128, erratum in FEBS Lett. 1992, 301, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Hashi, H.; Hatai, M.; Kimizuka, F.; Kato, I.; Yaoi, Y. Angiogenic activity of a fusion protein of the cell-binding domain of fibronectin and basic fibroblast growth factor. Cell Struct. Funct 1994, 19, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Elloumi, I.; Kobayashi, R.; Funabashi, H.; Mie, M.; Kobatake, E. Construction of epidermal growth factor fusion protein with cell adhesive activity. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3451–3458. [Google Scholar]

- Hannachi Imen, E.; Nakamura, M.; Mie, M.; Kobatake, E. Construction of multifunctional proteins for tissue engineering: Epidermal growth factor with collagen binding and cell adhesive activities. J. Biotechnol 2009, 139, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lonkhuyzen, D.R.; Hollier, B.G.; Shooter, G.K.; Leavesley, D.I.; Upton, Z. Chimeric vitronectin:insulin-like growth factor proteins enhance cell growth and migration through co-activation of receptors. Growth Factors 2007, 25, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Ogiwara, K.; Nagaoka, M.; Cho, C.S.; Akaike, T. Construction of a novel extracellular matrix using a new genetically engineered epidermal growth factor fused to IgG-Fc. Biotechnol. Lett 2005, 27, 1633–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, M.; Jiang, H.L.; Hoshiba, T.; Akaike, T.; Cho, C.S. Application of recombinant fusion proteins for tissue engineering. Ann. Biomed. Eng 2010, 38, 683–693. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, M.; Hagiwara, Y.; Takemura, K.; Murakami, Y.; Li, J.; Duncan, S.A.; Akaike, T. Design of the artificial acellular feeder layer for the efficient propagation of mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 26468–26476. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, K.; Nagaoka, M.; Cho, C.S.; Akaike, T. An artificial extracellular matrix created by hepatocyte growth factor fused to IgG-Fc. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 802–809. [Google Scholar]

- Minato, A.; Ise, H.; Goto, M.; Akaike, T. Cardiac differentiation of embryonic stem cells by substrate immobilization of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 with elastin-like polypeptides. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 515–523. [Google Scholar]

- Doheny, J.G.; Jervis, E.J.; Guarna, M.M.; Humphries, R.K.; Warren, R.A.; Kilburn, D.G. Cellulose as an inert matrix for presenting cytokines to target cells: Production and properties of a stem cell factor-cellulose-binding domain fusion protein. Biochem. J 1999, 339, 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Segvich, S.; Kohn, D.H. Phage Display as a Strategy for Designing Organic/Inorganic Biomaterials. In Biological Interactions on Materials Surfaces—Understanding and Controlling Protein, Cell, and Tissue Responses; Puleo, D.A., Bizios, R., Eds.; Springer Sciences + Business Media: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, D.; Dickerson, M.B.; Cai, Y.; Jones, S.E.; Ernst, E.M.; Vernon, J.P.; Michael, S.; Haluska, M.S.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J.; Subramanyam, G.; Naik, R.R.; Sandhag, K.H. Rapid bioenabled formation of ferroelectric BaTiO3 at room temperature from an aqueous salt solution at near neutral pH. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Su, X.; Neoh, K.G.; Choe, W.S. QCN-D analysis of binding mechanism of phage particles displaying a constrained heptapeptide with specific affinity to SO2 and TiO2. Anal. Chem 2006, 78, 4872–4879. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, R.; Ornek, D.; Wood, K. Aluminum- and mild steel-binding peptides from phage display. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2005, 68, 505–509. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C.; Flynn, C.E.; Hayhurst, A.; Sweeny, R.; Qi, J.; Georgiou, G.; Iverson, B.; Belcher, A.M. Viral assembly of oriented quantum dot nanowires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6946–6951. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.W.; Mao, C.; Flynn, C.E.; Belcher, A.M. Ordering of quantum dots using genetically engineered viruses. Science 2002, 296, 892–895. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley, S.R.; English, D.S.; Hu, E.L.; Barbara, P.F.; Belcher, A.M. Selection of peptides with semiconductor binding specificity for directed nanocrystal assembly. Nature 2000, 405, 665–668. [Google Scholar]

- Seker, U.O.; Wilson, B.; Dincer, S.; Kim, I.W.; Oren, E.E.; Evans, J.S.; Tamerler, C.; Sarikaya, M. Adsorption behavior of linear and cyclic genetically engineered platinum binding peptides. Langmuir 2007, 23, 7895–7900. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, P.; Yang, W. Biomimetic synthesis silver crystallite by peptide AYSSGAPPMPPF immobilized on PET film in vitro. J. Inorg. Biochem 2005, 99, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, R.R.; Stringer, S.J.; Agarwal, G.; Jones, S.E.; Stones, M.O. Biomimetic synthesis and patterning of silver nanoparticles. Nat. Mater 2001, 1, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kjærgaard, K.; Sørensen, J.K.; Schembri, M.A. Sequestration of zinc oxide by fimbrial designer chelators. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2000, 66, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.; Choe, W.-S.; Thai, C.K.; Sarikaya, M.; Traxler, B.A.; Baneyx, F.; Schwartz, D.T. Nonequilibrium synthesis and assembly of hybrid inorganic-protein nanostructures using an engineered DNA binding protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 15637–15643. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. Engineered iron oxide-adhesion mutants of the Escherichia coli phage lambda receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 8651–8655. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, K.-I.; Sasaki, H.; Shiba, K. Specificity and biomineralization activities of Ti-binding peptide-1 (TBP-1). Langmuir 2005, 21, 3090–3095. [Google Scholar]

- Segvich, S.; Biswas, S.; Becker, U.; Kohn, D. Identification of peptides with targeted adhesion to bone-like mineral via phage display and computational modeling. Cell. Tissue Org 2009, 189, 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.D.; Stanley, S.K.; Amis, E.J.; Becker, M.L. Identification of a highly specific hydroxyapatite-binding peptide using phage display. Adv. Mater 2008, 20, 1830–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi, K.; Tsuji, T.; Shiba, K. Directional BMP-2 for functionalization of titanium surfaces. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, R.B. Solid phase peptide synthesis. I. The synthesis of a tetrapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1963, 85, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, S.B.H. Total chemical synthesis of proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, M.; Bertozzi, C.R. Bringing chemistry to life. Nat. Meth 2011, 8, 638–642. [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi, C.R. A decade of bioorthogonal chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 651–653. [Google Scholar]

- Sletten, E.M.; Bertozzi, C.R. From mechanism to mouse: A tale of two bioorthogonal reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 6974–6998. [Google Scholar]

- Algar, W.R.; Prasuhn, D.E.; Stewart, M.H.; Jennings, T.L.; Blanco-Canosa, J.B.; Dawson, P.E.; Medintz, I.L. The controlled display of biomolecules on nanoparticles: A challenge suited to bioorthogonal chemistry. Bioconjonct. Chem 2011, 22, 825–858. [Google Scholar]

- Focke, P.J.; Valiyaveetil, F.I. Studies of ion channels using expressed protein ligation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14, 797–802. [Google Scholar]

- Yaoung, T.S.; Schultz, P.G. Beyond the canonical 20 amino acids: Expanding the genetic lexicon. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 11039–11044. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.C.; Schultz, P.G. Adding new chemistries to the genetic code. Ann. Rev. Biochem 2010, 89, 413–444. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y.; Sugimura, N.; Kwon, O.H.; Imanishi, Y. Enzyme modification by polymers with solubilities that change in response to photoirradiation in organic media. Nat. Biotechnol 1999, 17, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, S.; Andou, T.; Suzuki, T.; Dohmae, N.; Kobatake, E.; Ito, Y. Genetic PEGylation; Nano Medical Engineering Laboratory, RIKEN Advanced Science Institute: Saitama, Japan, Unpublished work; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Veronese, F.M.; Mero, A. The impact of PEGylation on biological therapies. Biodrugs 2008, 22, 315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, R.M.; Grover, G.N.; Maynard, H.D. Emerging synthetic approaches for protein –polymer conjugations. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 2212–2226. [Google Scholar]

- Klok, H.-A. Peptide/protein–synthetic polymer conjugates: Quo vadis. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 7990–8000. [Google Scholar]

- Joralemon, M.J.; McRae, S.; Emrick, T. PEGylated polymers for medicine : from conjugation to self-assembled systems. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 1377–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Velonia, K. Protein-polymer amphiphilic chimeras: Recent advances and future challenges. Polym. Chem 2010, 1, 944–952. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi, M.; Kitajima, T.; Nagamune, T.; Ito, Y. Recombinant hBMP4 incorporated with non-canonical amino acid for binding to hydroxyapatite. Biotechnol. Lett 2011, 33, 1885–1890. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, T.; Okazaki, M.; Nakahira, A.; Sasaki, J.; Egusa, H.; Sohmura, T. Modification of apatite materials for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery carriers. Curr. Med. Chem 2007, 14, 2726–2733. [Google Scholar]

- Kamitakahara, M.; Ohtsuki, C.; Miyazaki, T. Coating of bone-like apatite for development of bioactive materials for bone reconstruction. Biomed. Mater 2007, 2, R17–R23. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, P.A.; Johnsson, M.; Levine, M.J.; Nancollas, G.H. Salivary statherin. Dependence on sequence, charge, hydrogen bonding potency, and helical conformation for adsorption to hydroxyapatite and inhibition of mineralization. J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267, 5968–5976. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, W.J.; Long, J.R.; Dindot, J.L.; Campbell, A.A.; Stayton, P.S.; Drobny, G.P. Determination of statherin N-terminal peptide conformation on hydroxyapatite crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, M.; Shaw, W.J.; Long, J.R.; Nelson, K.; Drobny, G.P.; Giachelli, C.M.; Stayton, P.S. Chimeric peptides of statherin and osteopontin that bind hydroxyapatite and mediate cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 16213–16218. [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian, S.K.; Liu, G.; Ton-That, H.; Schneewind, O. Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science 1999, 285, 760–763. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, R.; Subramanian, S.; Boder, E.T. Sortase A as a novel molecular “stapler” for sequence-specific protein conjugation. Bioconjug Chem 2007, 18, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Tsukiji, S.; Nagamune, T. Site-specific protein modification on living cells catalyzed by sortase. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 802–807. [Google Scholar]

- Proft, T. Sortase-mediated protein ligation: An emerging biotechnology tool for protein modification and immobilisation. Biotechnol. Lett 2010, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.M.; Jones, P.A. Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell 1979, 17, 771–779. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, S.; Wills, A.J.; Edwards, D.R.; Heath, J.K.; Hogan, B.L. Developmental expression of 2ar (osteopontin) and SPARC (osteonectin) RNA as revealed by in situ hybridization. J. Cell Biol 1988, 106, 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T.; Terai, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Harada, K.; Kitajima, T. Delivery of a growth factor fusion protein having collagen-binding activity to wound tissues. Artif. Organs 2003, 27, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Lin, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, B.; Zhao, W.; Han, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Dai, J. Collagen membranes loaded with collagen-binding human PDGF-BB accelerate wound healing in a rabbit dermal ischemic ulcer model. Growth Factors 2007, 25, 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawara, N.; Ueda, H.; Shinozaki, S.; Kitajima, T.; Ito, Y.; Asaoka, H.; Kawakami, A.; Kaneko, E.; Shimokado, K. Hepatocyte growth factor fusion protein having collagen-binding activity (CBD-HGF) accelerates re-endothelialization and intimal hyperplasia in balloon-injured rat carotid artery. J. Atheroscler. Thromb 2007, 14, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, T.; Gilbert, T.W.; Schwartzman, D.; McTiernan, C.F.; Kitajima, T.; Ito, Y.; Sawa, Y.; Badylak, S.F.; Zenati, M.A. A fusion protein of hepatocyte growth factor enhances reconstruction of myocardium in a cardiac patch derived from porcine urinary bladder matrix. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg 2008, 136, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, W.; Sun, W.; Dai, J. Homogeneous osteogenesis and bone regeneration by demineralized bone matrix loading with collagen-targeting bone morphogenetic protein-2. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y.; Liu, S.Q.; Imanishi, Y. Enhancement of cell growth on growth factor-immobilized polymer. Biomaterials 1991, 12, 449–453. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y.; Zheng, J.; Imanishi, Y.; Yonezawa, K.; Kasuga, M. Protein-free cell culture on artificial substrata immobilized with insulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3598–3560. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y. Surface micropatterning to regulate cell functions. Biomaterials 1999, 2, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y. Covalently immobilized biosignal molecule materials for tissue engineering. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y. Growth Factors on Biomaterial Scaffolds. In Biological Interactions on Materials Surfaces: Understanding and Controlling Protein, Cell and Tissue Responses; Puleo, D., Bizios, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 173–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y. Growth Factors and Protein Modified Surfaces and Interfaces. In Comprehensive Biomaterials; Ducheyne, P., Healy, K.E., Hutmacher, D.W., Grainger, D.W., Kirkpatrick, C.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 247–279. [Google Scholar]

- Joddar, B.; Ito, Y. Biological modifications of materials surfaces with proteins for regenerative medicine. J. Mater. Chem 2011, 21, 13737–13755. [Google Scholar]

| Binding target | Growth factor | Fused polypeptide | Origin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural substrate | Collagen Gelatin | TGFβ1 [7,8], EGF [9], bFGF [10], BMP3 [11] | CBD polypeptide a (10 amino acids) | vWF |

| EGF [12], bFGF [13] | CBD (20 kDa) | Bacterial collagenase | ||

| PDGF [14], bFGF[15], BMP2 [16], NGF [17], BDNF [18], EGF [19], VEGF [20], NT3 [21] | CBD polypeptide b (7 amino acids) | Human collagenase | ||

| EGF [22], HGF [23], VEGF [24] | CBD (40 or 27 kDa) | Fibronectin | ||

| Fibrin Fibrinogen | NGF [25], BMP2 [26], KGF [27], VEGF [28,29,30], ephrin B2 [31], IGF-I [32] | FXIIIa substrate sequence c (8 or 12 amino acids) | α2-plasmin inhibitor | |

| EGF [33] | FBD (11 kDa) | Fibronectin | ||

| Cell (integrin) | EGF [34], bFGF [35] | Cell-binding domain (30 kDa) | Fibronectin | |

| EGF [36,37] | Cell adhesive sequence d | Fibronectin | ||

| Cell (integrin and IGF-I receptor) | IGF-I [38] | Vitronectin (full size) | Vitronectin | |

| Artificial substrate | Solid surface | EGF [39,40], LIF [41], HGF [42] | Fc region | Immunoglobulin |

| EGF [36,37], IGFBP4 [43] | Elastin-like polypeptide f (artificial) | Elastin | ||

| Cellulose | SCF [44] (extracellular domain) | Cellulose-binding domain | Bacterial xylanase | |

| Peptide sequence | Binding target | References |

|---|---|---|

| HQPANDPSWYTG/NTISGLRYAPHM | BaTiO3 | 46 |

| CRRWESKRC | SiO2 | 47 |

| CTKRNNKRC/CHKKPSKSC | TiO2 | 47 |

| VPSSGPQDTRTT | Aluminum/steel | 48 |

| CNNPMHQNC/VISNHAESSRRL/SLTPLTTSHLRS | Semiconductor | 49–51 |

| PTSTGQA/CPTSTGQAC | Platinum | 52 |

| AYSSGAPPMPPF | Silver | 53,54 |

| YDSRSMRPH | ZnO | 55 |

| CGPRHTDGLRRIAARGPC | Cu2O | 56 |

| RRTVKHHVN | Fe2O3 | 57 |

| RKLPDAPGMHTW | TiO2/Si/Ag | 58 |

| SVSVGMKPSPRP | Hydroxyapatite and tooth enamel | 59 |

| VTKHLNQISQSY | Hydroxyapatite and bone-like minerals | 60 |

© 2012 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Tada, S.; Kitajima, T.; Ito, Y. Design and Synthesis of Binding Growth Factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6053-6072. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13056053

Tada S, Kitajima T, Ito Y. Design and Synthesis of Binding Growth Factors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012; 13(5):6053-6072. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13056053

Chicago/Turabian StyleTada, Seiichi, Takashi Kitajima, and Yoshihiro Ito. 2012. "Design and Synthesis of Binding Growth Factors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 13, no. 5: 6053-6072. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13056053

APA StyleTada, S., Kitajima, T., & Ito, Y. (2012). Design and Synthesis of Binding Growth Factors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 13(5), 6053-6072. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13056053