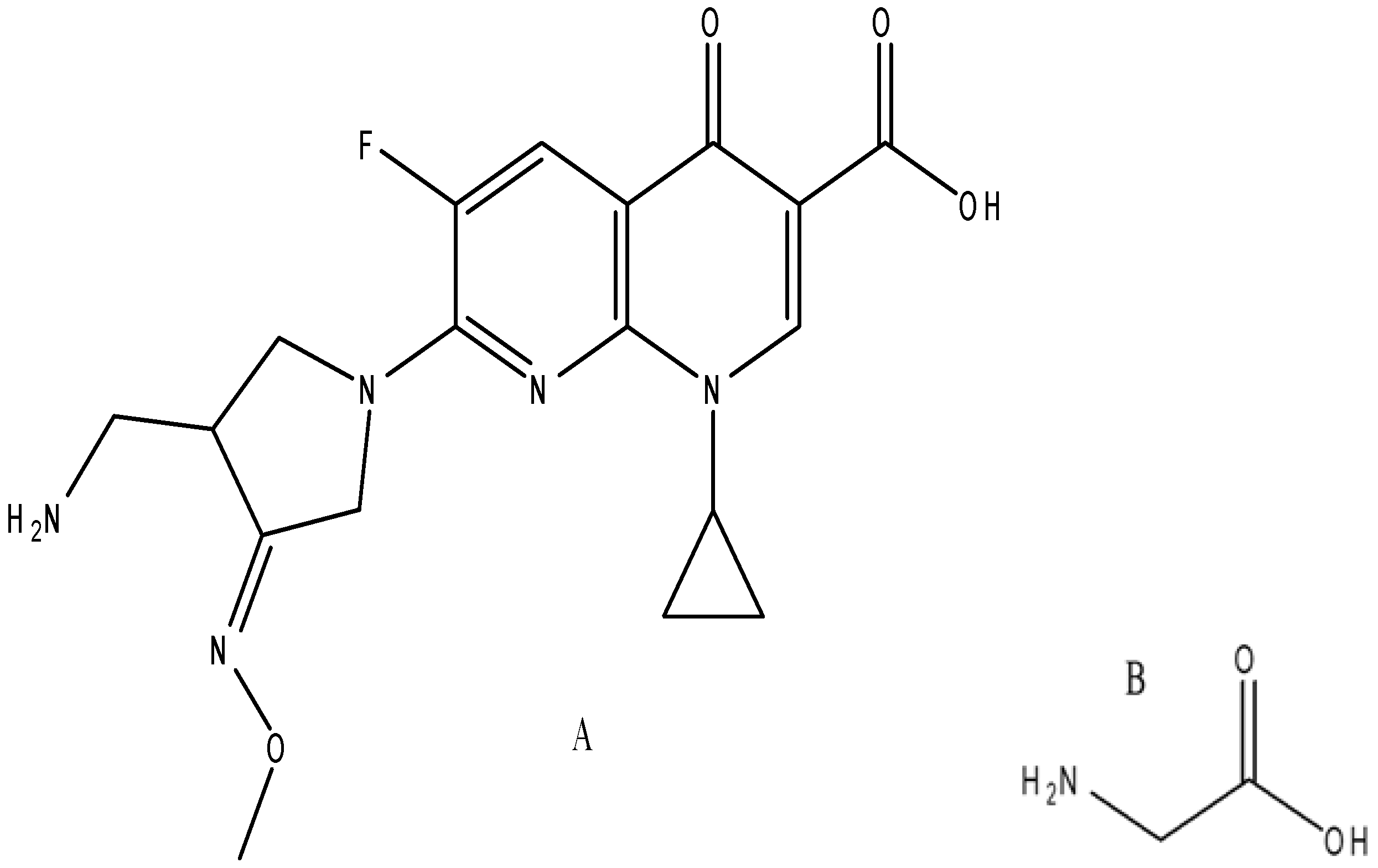

Synthesis, Spectroscopic, and Biological Studies of Mixed Ligand Complexes of Gemifloxacin and Glycine with Zn(II), Sn(II), and Ce(III)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

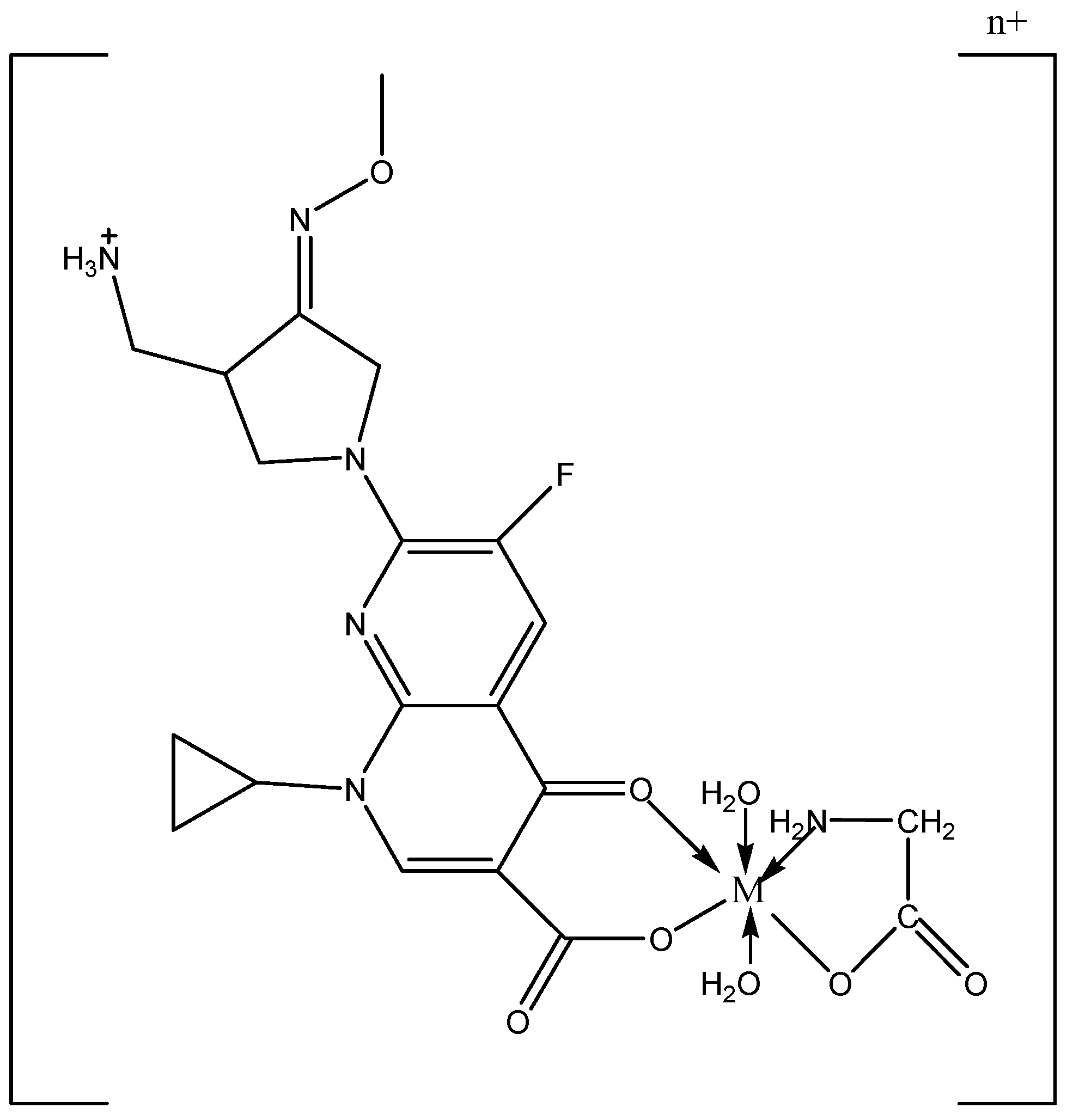

2. Results and Discussion

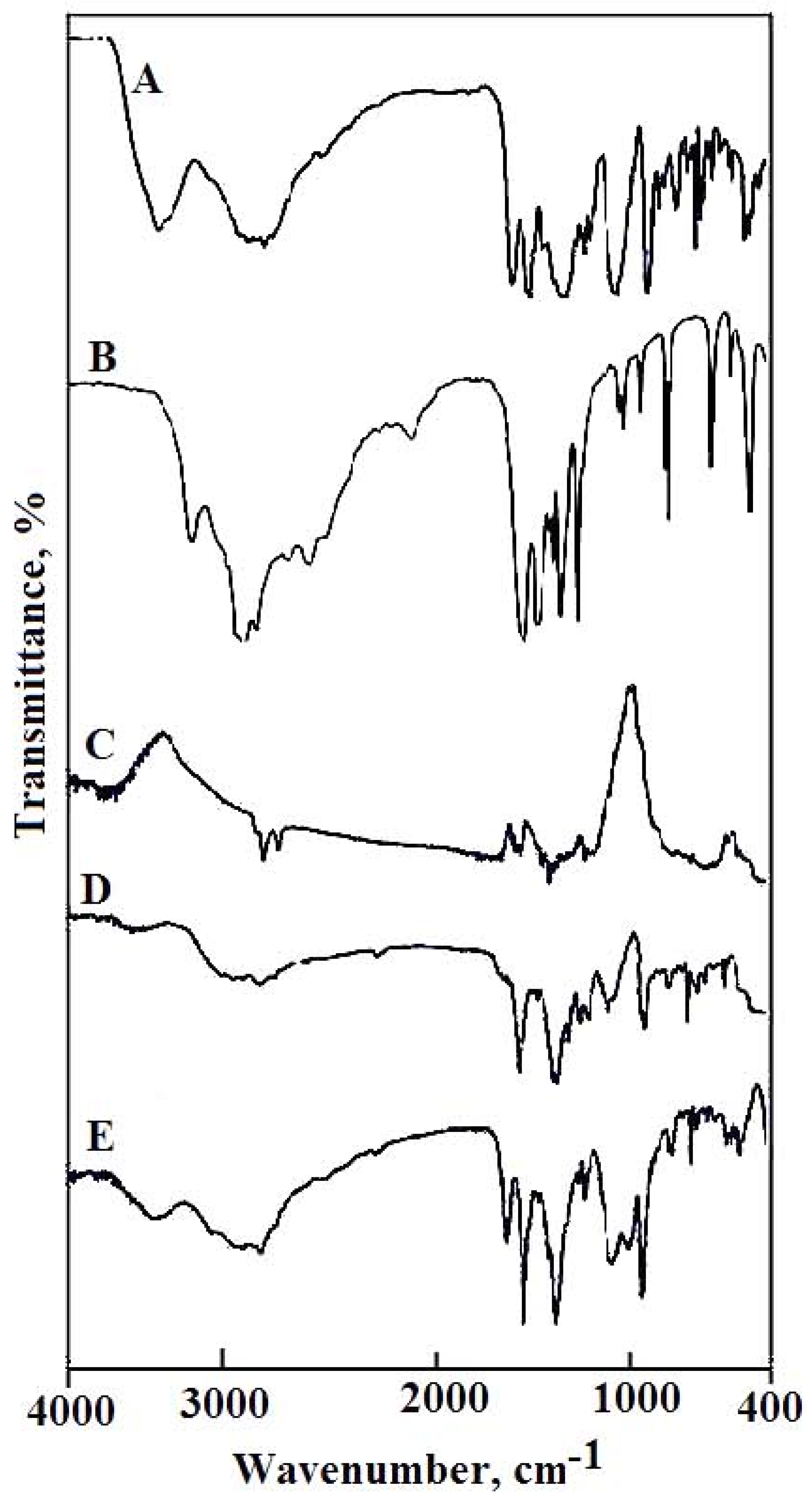

2.1. Infrared Absorption Spectra

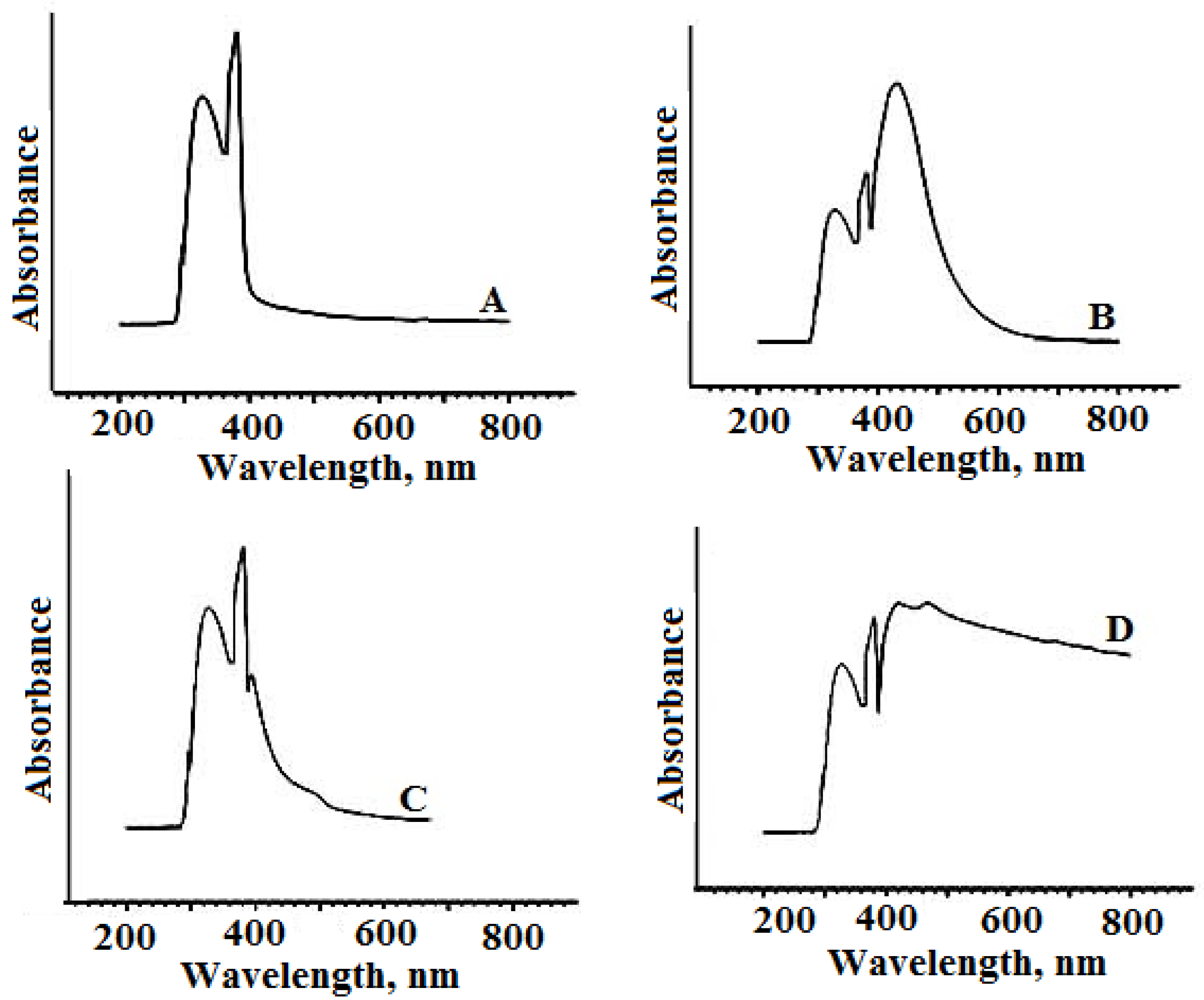

2.2. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy Analysis

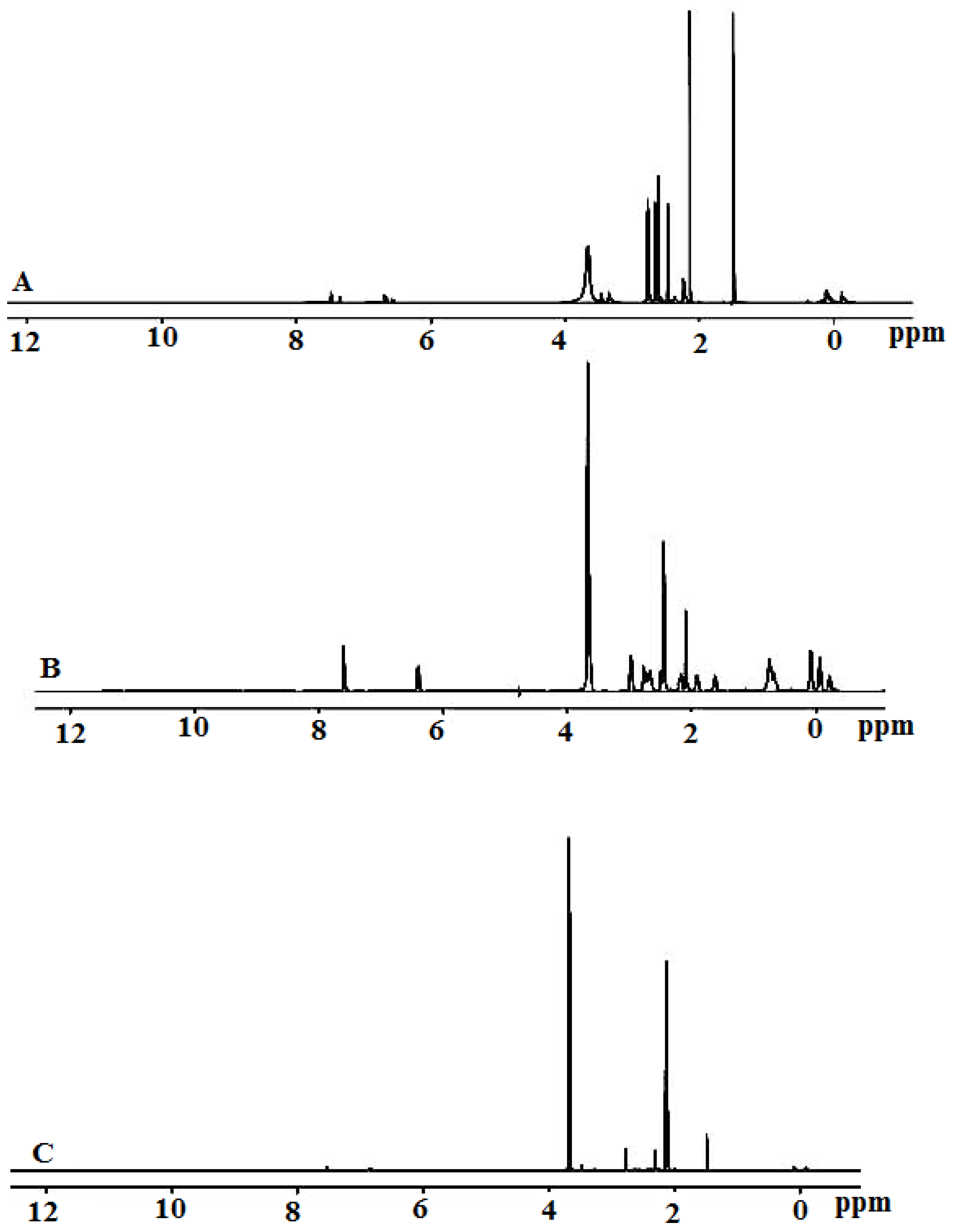

2.3. Proton-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra Analysis

2.4. Biological Activities

2.4.1. Antibacterial Activity

2.4.2. Antifungal Activity

2.4.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Fungicidal Activity

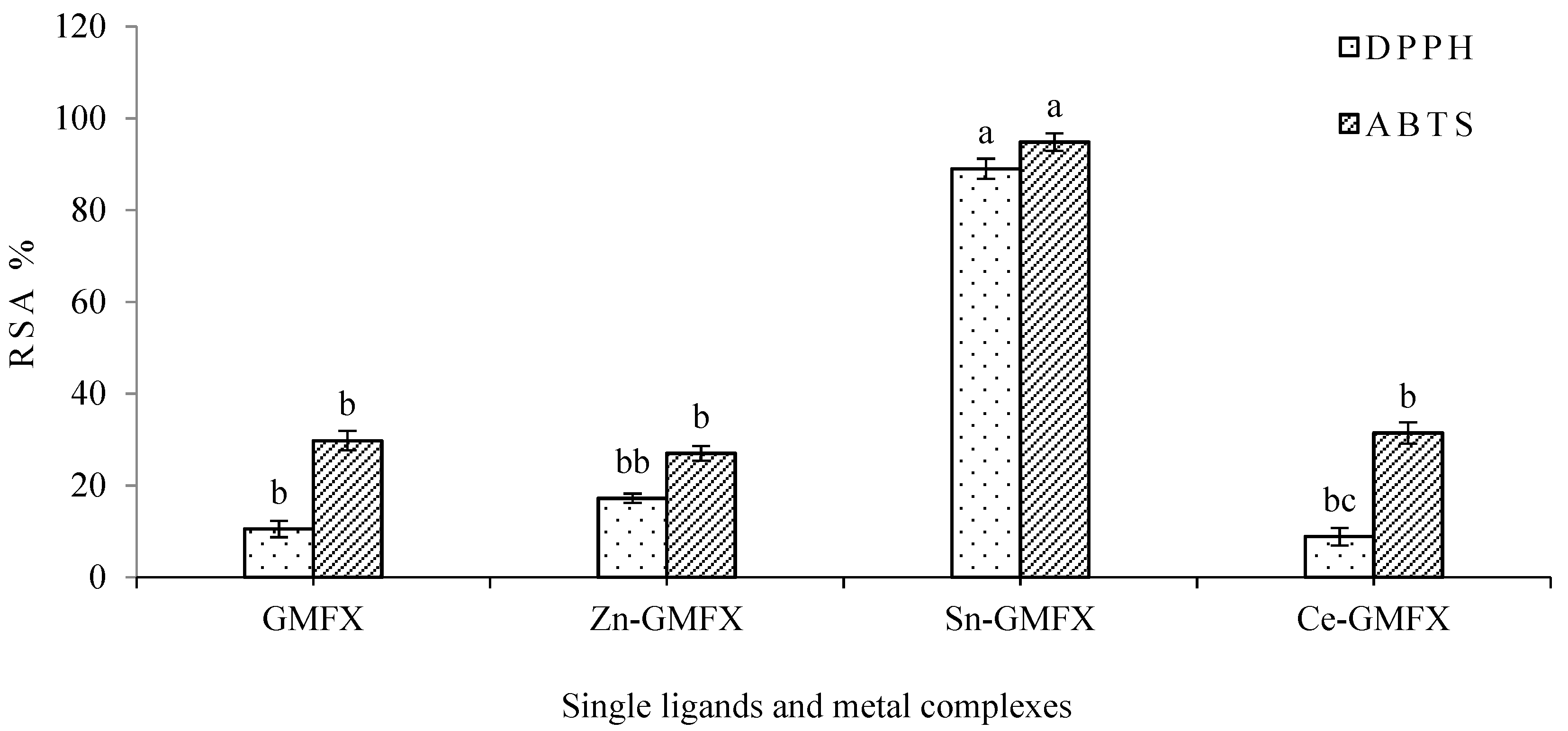

2.4.4. Antioxidant Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of Mixed Ligand Metal Complexes

3.3. Instruments

3.4. Antimicrobial Investigation

3.4.1. Bactericidal Activity Test

3.4.2. Fungicidal Activity Test

3.4.3. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (96-Well Microplate Method)

3.4.4. Antioxidant Activity

DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl Assay

ABTS: 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-acid) Assay

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Psomas, G.; Tarushi, A.; Efthimiadou, E.K. Synthesis, characterization and DNA-binding of the mononuclear dioxouranium(VI) complex with ciprofloxacin. Polyhedron 2008, 27, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesher, G.Y.; Froelich, E.J.; Gruett, M.D.; Bailey, J.H.; Brundage, R.P. 1,8-Naphthyridine derivatives: A new class of chemotherapeutic agents. J. Med. Pharm. Chem. 1962, 5, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Chiller, T.M.; Powers, J.H.; Angulo, F.J. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species and the withdrawal of fluoroquinolones from use in poultry: A public health success story. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 447, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turel, I. The interactions of metal ions with quinolone antibacterial agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 232, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriole, V.T. (Ed.) The Quinolones, 3rd ed.; Chapter 16 the Quinolones: Prospects; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 477–495. ISBN 978-0-12-059517-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, J.; Schaefer, H.G.; Beermann, D. Quinolone Antibacterials; Chapter 11 Clinical Pharmacology; Kuhlmann, J., Dalhoff, A., Zeile, A.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998; Volume 127, pp. 339–406. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.M.; Jones, R.N.; Erwin, M.E. Anti-streptococcal activity of SB-265805 (LB20304), a novel fluoronaphthyridone, compared with five other compounds, including quality control guidelines. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 33, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, R.; Rotschafer, J.; Tan, J. Antimicrobial treatment of lower respiratory tract infections in the hospital setting. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, Y.K.; Hsu, Y.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, T.C.; Wang, J.Y.; Kuo, P.L. Gemifloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial drug, inhibits migration and invasion of human colon cancer cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.N.; Singh, N.; Shukla, K.K.; Gundla, V.L.N.; Chauhan, U.K. Synthesis, characterization and biological activity of ternary copper(II) complexes containing polypyridyl ligands. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2006, 63, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viossat, B.; Daran, J.; Savouret, G.; Morgant, G.; Greenaway, F.T.; Dung, N.; Pham-Tran, V.A.; Sorenson, J.R.J. Low-temperature (180 K) crystal structure, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and propitious anticonvulsant activities of CuII2(aspirinate)4(DMF)2 and other CuII2(aspirinate)4 chelates. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2003, 96, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimiza, F.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Tangoulis, V.; Psycharis, V.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Kessissoglou, D.P.; Psomas, G. Biological evaluation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-cobalt(II) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 4517–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turel, I.; Golobic, A.; Klavzar, A.; Pihlar, B.; Buglyo, P.; Tolis, E.; Rehder, D.; Sepcic, K. Interactions of oxovanadium(IV) and the quinolone family member—Ciprofloxacin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2003, 95, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gresa, M.P.; Ortiz, R.; Perello, L.; Latorre, J.; Liu-Gonzalez, M.; Garcia-Granda, S.; Perez-Priede, M.; Canton, E. Interactions of metal ions with two quinolone antimicrobial agents (cinoxacin and ciprofloxacin). Spectroscopic and X-ray structural characterization. Antibacterial studies. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2002, 92, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthimiadou, E.K.; Katsarou, M.E.; Karaliota, A.; Psomas, G. Copper(II) complexes with sparfloxacin and nitrogen-donor heterocyclic ligands: Structure-activity relationship. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008, 102, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthimiadou, E.K.; Thomadaki, H.; Sanakis, Y.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Katsaros, N.; Scorilas, A.; Karaliota, A.; Psomas, G. Structure and biological properties of the copper(II) complex with the quinolone antibacterial drug N-propyl-norfloxacin and 2,2′-bipyridine. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007, 101, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsarou, M.E.; Efthimiadou, E.K.; Psomas, G.; Karaliota, A.; Vourloumis, D. Novel copper(II) complex of N-propyl-norfloxacin and 1,10-phenanthroline with enhanced antileukemic and DNA nuclease activities. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, G.G.; Abd El-Halim, H.F.; El-Dessouky, M.M.I.; Mahmoud, W.H. Synthesis and characterization of mixed ligand complexes of lomefloxacin drug and glycine with transition metals. Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxicity studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 999, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, W.J. The use of conductivity measurements in organic solvents for the characterisation of coordination compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1971, 7, 81–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dief, A.M.; Nassr, L.A.E. Tailoring, physicochemical characterization, antibacterial and DNA binding mode studies of Cu(II) Schiff bases amino acid bioactive agents incorporating 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2015, 12, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uivarosi, V. Metal Complexes of Quinolone Antibiotics and Their Applications: An Update. Molecules 2013, 18, 11153–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhunia, A.K.; Johnson, M.C.; Ray, B. Purification, characterization and microbial spectrum of a bacteriocin produced byPediococcus acidilactici. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1988, 65, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, L. Infrared spectra of inorganic and coordination compounds. J. Chem. Educ. 1963, 40, 501. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeek, S.A.; EL-Shwiniy, W.H.; El-Attar, M.S. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial investigation of some moxifloxacin metal complexes. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 84, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeek, S.A.; EL-Shwiniy, W.H. Metal complexes of the fourth generation quinolone antimicrobial drug gatifloxacin: Synthesis, structure and biological evaluation. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 977, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, B.; Martinez, M.; Sanchez, A.; Dominguez, A. A physico-chemical study of the interaction of ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin with polivalent cations. Int. J. Pharm. 1994, 106, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Turel, I.; Bukovec, N.; Farkas, E. Complex formation between some metals and a quinolone family member (ciprofloxacin). Polyhedron 1996, 15, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Adam, M.S.; Hamdan, S.K. Some New Nano-sized Mononuclear Cu(II) Schiff Base Complexes: Design, Characterization, Molecular Modeling and Catalytic Potentials in Benzyl Alcohol Oxidation. Catal. Lett. 2016, 146, 1373–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Moustafa, H.; Hamdan, S.K. Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes with ONNO asymmetric tetradentate Schiff base ligand: Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, theoretical calculations, DNA interaction and antimicrobial studies. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 2017, 31, e3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, V.I.; Radysh, H.V. Treatment of drug resistant destructive pulmonary tuberculosis: Gemifloxacin and other fluoroquinolones clinical efficiency and tolerance at the end of initial phase of treatment. Likar. Sprav. 2013, 8, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kasselouri, S.; Hadjiliadis, N. Interaction of cis-Pd(guo)2Cl2 with amino acids. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1990, 168, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, L.J. The Infrared Spectra of Complex Molecules, 3rd ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; El-Khatib, R.M.; Nassr, L.A.E.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Lashin, F.E. Design, characterization, teratogenicity testing, antibacterial, antifungal and DNA interaction of few high spin Fe(II) Schiff base amino acid complexes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2013, 111, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Aboelez, M.O.; Abdel-Mawgoud, A.H. DNA interaction, antimicrobial, anticancer activities and molecular docking study of some new VO(II), Cr(III), Mn(II) and Ni(II) mononuclear chelates encompassing quaridentate imine ligand. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2017, 170, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, B.; Villa, M.V.; Rubio, I.; Castineiras, A.; Borras, J. Complexes of Ni(II) and Cu(II) with ofloxacin Crystal structure of a new Cu(II) ofloxacin complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001, 84, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.; Goodfield, J.; Williams, D.R.; Midley, J.M. The complexation of transition series metal ions by nalidixic acid. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1984, 92, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeek, A.S.; Abd El-Hamid, S.M.; El-Aasser, M.M. Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial and cytotoxicity studies of some transition metal complexes with gemifloxacin. Monatsh Chem. 2015, 146, 1967–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumer, M.; Koksal, H.; Sener, M.K.; Serin, S. Antimicrobial activity studies of the binuclear metal complexes derived from tridentate Schiff base ligands. Transit. Met. Chem. 1999, 24, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Iqbal, J.; Iqbal, S.; Ijaz, N. In Vitro Antibacterial studies of ciprofloxacin-imines and their complexes with Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II), and Zn(II). Turk. J. Biol. 2007, 31, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, N.H.; Parekh, H.M.; Patel, M.N. Synthesis, physicochemical characteristics, and biocidal activity of some transition metal mixed-ligand complexes with bidentate (NO and NN) Schiff bases. J. Pharm. Chem. 2007, 41, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.B.; Memon, S.; Mahroof-Tahir, M.; Bhanger, M.I. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity copper–quercetin complex. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spec. 2009, 71, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Sun, S.; Cao, W.; Liang, Y.; Song, J. Antioxidant property of quercetin-Cr(III) complex: The role of Cr(III) ion. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 918, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Bustamante, A.; Viveros-Paredes, J.M.; Flores-Parra, A.; Peraza-Campos, A.L.; Martínez-Martínez, F.J.; Sumaya-Martínez, M.T.; Ramos-Organillo, Á. Antioxidant activity of Butyl- and Phenylstannoxanes derivedfrom 2-, 3- and 4-Pyridinecarboxylic acids. Molecules 2010, 15, 5445–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; El-Khatib, R.M.; Nassr, L.A.E.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Ismael, M.; Seleem, A.A. Metal based pharmacologically active agents: Synthesis, structural characterization, molecular modeling, CT-DNA binding studies and in vitro antimicrobial screening of iron(II) bromosalicylidene amino acid chelates. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 117, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; El-Khatib, R.M.; Abdel-Fatah, S.M. Sonochemical synthesis, DNA binding, antimicrobial evaluation and in vitro anticancer activity of three new nano-sized Cu(II), Co(II) and Ni(II) chelates based on tri-dentate NOO imine ligands as precursors for metal oxides. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 162, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zygadlo, J.A.; Guzman, C.A.; Grosso, N.R. Antifungal properties of the leaf oils of Tagetes minuta L. and Tagetes filifolia Lag. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1994, 6, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, J.; Järvinen, S.; Virta, M.; Lilius, E.M. Real-time monitoring of antimicrobial activity with the multiparameter microplate assay. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2006, 66, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martysiak-Żurowska, D.; Wenta, W. Comparison of ABTS and DPPH methods for assessing the total antioxidant capacity of human milk. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2012, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bafna, A.; Mishra, S. Actividad antioxidante in vitro del extracto de metanol de los rizomas de Curculigo orchioides Gaertn. ARS Pharm. 2005, 46, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Newair, E.F.; Hamdan, S.K. Some new nano-sized Cr(III), Fe(II), Co(II), and Ni(II) complexes incorporating 2-((E)-(pyridine-2-ylimino)methyl)napthalen-1-ol ligand: Structural characterization, electrochemical, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral assessment and DNA interaction. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 160, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds M.wt. and M.F. | Yield% | Mp/°C | Color | Found (Calcd.) (%) | μeff (B. M.) | Λ S cm2 mol−1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | M | Cl | ||||||

| GMFX 389.4 (C18H20FN5O4) | - | 220 | White brown | 55.50 (55.52) | 5.18 (5.17) | 17.98 (17.99) | - | - | - | 47.50 |

| Gly 75.07 (C2H5NO2) | - | 233 | White | 31.98 (32.00) | 6.64 (6.66) | 18.63 (18.66) | - | - | - | 50.77 |

| (1) 619.89 (ZnC20H31N6O9FCl) | 78 | 310 | Faint yellow | 38.69 (38.71) | 4.97 (5.00) | 13.49 (13.55) | 10.50 (10.55) | 5.72 (5.72) | - | 97.58 |

| (2) 655.20 (SnC20H29N6O8FCl) | 82 | 330 | Faint brown | 36.60 (36.63) | 4.39 (4.42) | 12.79 (12.82) | 17.98 (18.11) | 5.38 (5.41) | - | 86.34 |

| (3) 730.10 (CeC20H31N6O9FCl2) | 95 | 340 | Beige | 32.82 (32.87) | 4.18 (4.24) | 11.42 (11.50) | 19.12 (19.19) | 9.70 (9.72) | 2.34 | 150.11 |

| A | B | C | D | E | Assignments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3533w | 3522w 3478w | 3341mbr | 3545w | 3375mbr | ν(O–H); H2O; COOH |

| 3156w | 3133vw | 3067vw | 3044sh | 3089vw | ν(N–H) |

| 3044w | 3009m | 3022w | |||

| 2943s | 2955m | 2889w | 2974m | 2955m | ν(C–H); aliphatic |

| 2867vw | 2843m | 2766w | 2871vw | 2822vw | |

| 2778m | 2767w | 2711vw | 2800m | 2756w | |

| 2712ms | 2722w | 2758w | 2716m | ||

| 2712m | |||||

| 1732vs | 1703vs | - | - | - | ν(C=O); COOH |

| - | 1620vs | 1620vs | 1622m | 1624s | νas(COO−) |

| 1624vs | 1589s | 1574s | 1574s | 1570vs | ν(C=N) |

| 1539m | |||||

| 1466vs | 1494s | 1485vs | 1462vs | 1485s | –CH; deformations of CH2 |

| 1474s | |||||

| 1385m | 1377s | 1393s | 1385vs | 1393s | νs(COO−) |

| 1367sh | 1378w | 1350sh | |||

| 1331ms | 1322m | 1304ms | 1300m | 1308s | δb(–CH2) |

| 1261vs | 1285s | 1269s | 1269s | 1265s | ν(C–O), ν(C–N) and ν(C–C) |

| 1223w | 1211sh | 1189vw | 1184m | 1184m | |

| 1188m | 1172vw | 1144w | 1146m | 1146m | |

| 1156m | 1146ms | ||||

| 1089m | 1034s | 1103m | 1038ms | 1107m | δr(–CH2) |

| 1034s | 1072sh | 1034s | |||

| 1038m | |||||

| 989vw | 989w | 989vw | 945ms | 945s | –CH-bend; phenyl |

| 968m | 937ms | 941ms | 899m | 895m | |

| 933m | 894w | 911vw | 844m | 829m | |

| 887ms | 867m | 829m | 822w | ||

| 833ms | 833ms | 800vw | |||

| 822vw | |||||

| 795m | 783m | 779m | 778w | 778m | δb(COO−) |

| 767vw | 721s | 745s | 752m | 748s | |

| 748m | 710w | 711m | 710m | ||

| 710m | |||||

| 656w | 644vw | 625ms | 633ms | 667vw | ν(M–O). ν(M–N) and ring deformation |

| 622m | 621ms | 578m | 583m | 629m | |

| 571ms | 559s | 544w | 544w | 578w | |

| 550vw | 494ms | 502m | 505s | 544m | |

| 486m | 436m | 478w | 478sh | 502m | |

| 478vw | 406m | 433w | 444vw | 478sh | |

| 436s | 413w | 422w | 440w |

| Assignments (nm) | GMFX | GMFX Metal Complexes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(II) | Sn(II) | Ce(III) | ||

| π–π* transitions | 326 | 332 | 330 | 332 |

| n–π* transitions | 380 | 390 | 388 | 392 |

| Ligand-metal charge transfer | - | 402 | 432 | 420, 468 |

| GMFX | Gly | Zn(II) | Sn(II) | Ce(III) | Assignments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.14–1.33 | - | 1.29–1.32 | 1.20–1.33 | 1.14–1.33 | δH.–CH2 and –CH cyclopropane |

| 2.71 | 2.00 | 2.71 | 2.72 | 2.71 | δH.–+NH2 |

| 3.32–3.36 | 3.59 - | 3.32–3.84 4.59 | 3.36–3.99 4.89 | 3.21–3.99 4.50 | δH.–CH2 aliphatic δH. H2O |

| 8.02–8.72 | - | 8.40–8.71 | 8.40–8.71 | 8.40–8.71 | δH.–CH aromatic |

| 11 | 11 | - | - | - | δH.–COOH |

| Bacterial Growth Inhibition % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G−ve | G+ve | |||

| Treatments µg/mL | E. coli | X. campestris | C. michiganensis | B. megaterium |

| GMFX 10,000 | 68.9 ± 0.1b | 75.6 ± 0.1ab | 90.0 ± 0.9ab | 54.4 ± 0.2bc |

| GMFX 1000 | 61.1 ± 0.2bc | 57.8 ± 0.3bc | 86.0 ± 0.4b | 43.3 ± 0.1c |

| GMFX 100 | 55.5 ± 0.6c | 50.0 ± 0.2c | 85.0 ± 0.6b | 37.8 ± 0.1cd |

| Sn–GMFX 10,000 | 82.2 ± 0.3a | 82.2 ± 0.2a | 97.0 ± 0.7a | 56.7 ± 0.1bc |

| Sn–GMFX 1000 | 65.6 ± 0.2b | 62.2 ± 0.2bc | 86.0 ± 0.5b | 44.4 ± 0.1c |

| Sn–GMFX 100 | 52.2 ± 0.1c | 52.2 ± 0.1c | 84.0 ± 0.6b | 38.9 ± 0.2cd |

| Zn–GMFX 10,000 | 80.0 ± 0.1a | 83.3 ± 0.2a | 95.0 ± 0.8a | 57.8 ± 0.2bc |

| Zn–GMFX 1000 | 65.6 ± 0.1b | 60.0 ± 0.2bc | 89.0 ± 0.6ab | 48.9 ± 0.2c |

| Zn–GMFX 100 | 52.0 ± 0.4c | 51.1 ± 0.2c | 85.0 ± 0.4b | 37.8 ± 0.3cd |

| Ce–GMFX 10,000 | 83.0 ± 0.3a | 72.2 ± 0.2b | 98.0 ± 0.6a | 61.1 ± 0.2b |

| Ce–GMFX 1000 | 60.0 ± 0.2bc | 60.0 ± 0.3bc | 91.0 ± 0.0ab | 41.1 ± 0.1c |

| Ce–GMFX 100 | 50.0 ± 0.2c | 42.2 ± 0.1d | 92.0 ± 0.0ab | 30.0 ± 0.1d |

| Ampicillin 100 µg/mL | 80.0 ± 0.3a | 74.4 ± 0.3ab | 98.0 ± 0.5a | 32.2 ± 0.1cd |

| Streptomycin 50 µg/mL | 51.1 ± 0.1c | 55.6 ± 0.1bc | 96.0 ± 0.7a | 53.3 ± 0.1bc |

| Kanamycin 50 µg/mL | 68.9 ± 0.2b | 71.1 ± 0.2b | 98.0 ± 0.4a | 57.8 ± 0.1bc |

| Cephaloxacin 30 µg/mL | 53.3 ± 0.2c | 60.0 ± 0.2bc | 93.0 ± 0.9a | 84.0 ± 0.14a |

| Control KB | 0.0 ± 0.0d | 0.0 ± 0.0e | 0.0 ± 0.0c | 0.00 ± 0.0e |

| Fungal Mycelium Growth Inhibition % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conc. µg/mL | R. solani | S. sclerotiorum | A. niger | B. cinerea | P. digitatum | |

| GMFX | 1000 | 78.1 ± 0.22a | 71.9 ± 0.04ab | 69.0 ± 0.13a | 91.9 ± 0.13a | 95.3 ± 0.11a |

| 500 | 66.3 ± 0.18b | 34.4 ± 0.67b | 63.4 ± 0.13ab | 86.3 ± 0.09ab | 83.1 ± 0.13b | |

| 250 | 50.0 ± 0.0c | 0.0 ± 0.0d | 45.0 ± 0.36c | 60.6 ± 0.13b | 76.3 ± 0.09b | |

| Sn–GMFX | 1000 | 28.1 ± 0.22d | 6.3 ± 0.45cd | 56.9 ± 0.09b | 51.3 ± 0.09c | 76.3 ± 0.09b |

| 500 | 6.3 ± 0.0e | 0.0 ± 0.0d | 53.1 ± 0.09bc | 45.6 ± 0.13cd | 69.4 ± 0.13bc | |

| 250 | 0.0 ± 0.0f | 0.0 ± 0.0d | 48.4 ± 0.22bc | 37.5 ± 0.0d | 63.1 ± 0.04bc | |

| Zn–GMFX | 1000 | 15.6 ± 0.22de | 26.9 ± 0.31b | 65.6 ± 0.09ab | 51.3 ± 0.09c | 90.6 ± 0.13a |

| 500 | 7.5 ± 0.09e | 18.8 ± 1.34bc | 64.4 ± 0.09ab | 45.0 ± 0.09cd | 75.0 ± 0.18b | |

| 250 | 0.0 ± 0.0f | 11.3 ± 0.18c | 58.8 ± 0.36b | 37.5 ± 0.0d | 64.4 ± 0.13bc | |

| Ce–GMFX | 1000 | 43.1 ± 0.3cd1 | 21.9 ± 0.67b | 64.4 ± 0.09ab | 50.0 ± 0.0c | 71.3 ± 0.09b |

| 500 | 18.1 ± 0.13d | 12.5 ± 0.89c | 63.8 ± 0.18ab | 37.5 ± 0.0d | 65.6 ± 0.13bc | |

| 250 | 3.1 ± 0.22e | 6.3 ± 0.45cd | 41.6 ± 0.58c | 37.5 ± 0.0d | 61.3 ± 0.09c | |

| Azoxystrobin 1 µL/mL | 26.9 ± 0.13d | 26.9 ± 0.13d | 80.0 ± 0.09a | 72.2 ± 0.13a | 58.1 ± 0.13b | |

| Cycloheximide 0.1 µL/mL | 14.4 ± 0.13de | 14.4 ± 0.13de | 10.6 ± 0.31c | 49.7 ± 0.31bc | 46.9 ± 0.22cd | |

| PDA ctrl | 0.00 ± 0.0f | 0.00 ± 0.0f | 0.0 ± 0.0d | 0.0 ± 0.0cd | 0.0 ± 0.0d | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakr, S.H.; Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Sadeek, S.A. Synthesis, Spectroscopic, and Biological Studies of Mixed Ligand Complexes of Gemifloxacin and Glycine with Zn(II), Sn(II), and Ce(III). Molecules 2018, 23, 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051182

Sakr SH, Elshafie HS, Camele I, Sadeek SA. Synthesis, Spectroscopic, and Biological Studies of Mixed Ligand Complexes of Gemifloxacin and Glycine with Zn(II), Sn(II), and Ce(III). Molecules. 2018; 23(5):1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051182

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakr, Shimaa H., Hazem S. Elshafie, Ippolito Camele, and Sadeek A. Sadeek. 2018. "Synthesis, Spectroscopic, and Biological Studies of Mixed Ligand Complexes of Gemifloxacin and Glycine with Zn(II), Sn(II), and Ce(III)" Molecules 23, no. 5: 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051182