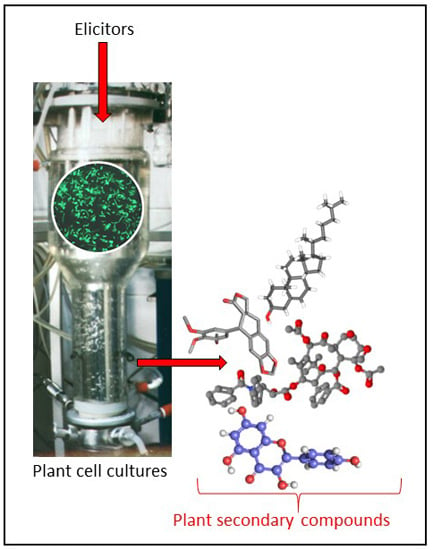

Elicitation, an Effective Strategy for the Biotechnological Production of Bioactive High-Added Value Compounds in Plant Cell Factories

Abstract

:1. Introduction

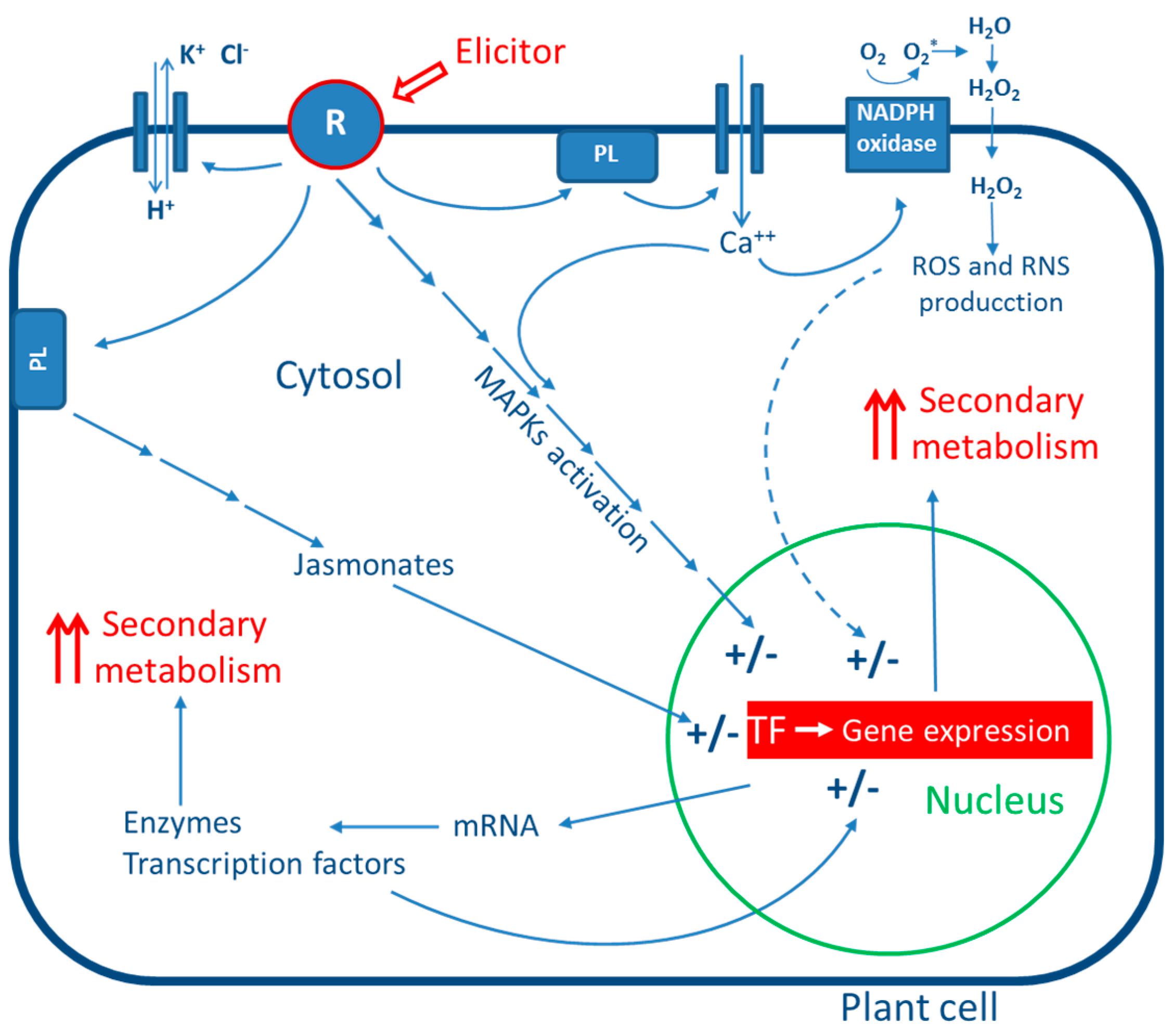

2. Elicitation

3. General Mechanism of Action of Elicitors

4. Biotic Elicitors

4.1. Plant Hormones

4.1.1. Methyl Jasmonate

4.1.2. Salicylic Acid

4.1.3. SA Derivatives and Analogs

4.1.4. Brassinosteroids

4.2. Microorganism-Derived Elicitors

4.2.1. Bacterial Extracts

4.2.2. Yeast Extract and Fungal Elicitors

4.2.3. Bacteria and Fungi-Derived Peptides and Proteins

4.3. Cell Wall-Derived Elicitors

4.3.1. Chitosan and Chitin

4.3.2. Oligosaccharins

4.3.3. Other Cell Wall Fragments

4.4. Other Elicitors

4.4.1. Plant Regulator Peptides

4.4.2. Cyclodextrins

| Elicitor | Culture System | Plant Species | Secondary Metabolites (SM) | Type of SM | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeJa | CS | Linum album | Podophyllotoxin; 6-methoxypodophyllotoxin | Polyphenols (Aryl tetralin-lignans) | [40] |

| HR | Linum tauricum | 4’-Dimethyl-6-methoxypodophyllotoxin; 6-methoxypodophyllotoxin | Polyphenols (Aryl tetralin-lignans) | [41] | |

| AR | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [43,44,45,46,47,48,49] | |

| HR | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [44,50] | |

| CS | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [42,51] | |

| CS | Taxus baccata Taxus media | Paclitaxel and related taxanes | Diterpene alkaloids | [54,55,56,57] | |

| HR | Hyoscyamos niger | Scopolamine and hyoscyamine | Tropane alkaloids | [59] | |

| CS | Vitis vinifera | trans-Resveratrol and stilbenes | Phenylpropanoids | [60] | |

| CS | Menthal x piperita | Rosmarinic acid | Phenylpropanoyl | [61] | |

| CS | Lavandula vera | Rosmarinic acid | Phenylpropanoyl | [62] | |

| CS | Thevetia peruviana | Peruvioside | Cardiac glycoside | [63] | |

| HR | Catharantus roseus | Catharanthine | Tropanic alkaloid | [64] | |

| CS | Centella asiatica | Centellosides (Madecassoside, Asiaticoside) | Triterperne saponines | [65,66] | |

| CS | Artemisia annua | Artemisinin | Sesquiterpene lactone | [67] | |

| SA | CS | Taxus chinensis Taxus baccata | Paclitaxel and related taxanes | Diterpene alkaloids | [72,73,74] |

| CS | Corylus avellana | Paclitaxel | Diterpene alkaloids | [75] | |

| CS | Linum album | Podophyllotoxin | Polyphenols (Aryl tetralin-lignans) | [76] | |

| HR; AR | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [77,78,79,80] | |

| CS | Gingkgo biloba | Bilobalide; ginkolide a, b | Sesquiterpenes | [81] | |

| CS; HR | Hypericum spp. | Cadensin G; Paxanthone | Xanthones | [82] | |

| CS | Vitis vinifera | Stilbenes | Phenylpropanoids | [83] | |

| AR | Withania somnifera | Withanolide a, b; withaferin a and whitanone | Withanolides | [84] | |

| CS | Stephania venosa | Dicentrine | Alkaloid | [85] | |

| CS | Hypericum perforatum | Hypericin; pseudohypericin | Naphtodianthrones | [86] | |

| Bacteria extracts | HR | Beta vulgaris | Betalaine | Alkaloid | [101] |

| HR | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [80] | |

| CS | Gingkgo biloba | Bilobalide; ginkolides | Sesquiterpenes | [100] | |

| HR | Salvia miltiorrihiza | Tanshinone | Diterpene | [102] | |

| HR; CS | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [28,80] | |

| CS | Linun album | Podophyllotoxin | Polyphenols (Aryl tetralin-lignans) | [29] | |

| CS | Silybum marianum | Silymarin | Flavonolignans | [30] | |

| HR | Artemisia annua | Artemisinin | Sesquiterpene lactone | [115] | |

| HR | Fagopyrum tataricum | Rutin; quercetin | Flavonoids | [104] | |

| HR | Salvia miltiorrihiza | Rosmarinic acid | Phenylpropanoids | [116] | |

| CS | Cayratia trifolia | Stilbene | Phenylpropanoids | [114] | |

| Fungal extract | CS | Hypericum perforatum | Hypericin; pseudohypericin | Naphtodianthrones | [105] |

| CS | Coleus forskohlii | Forskolin | Diterpene | [106] | |

| CS | Psoralea corylifolia | Psoralen | furocoumarins | [107] | |

| CS | Euphorbia pekinensis | Euphol | Terpenoids | [108] | |

| CS | Andrographis paniculata | Flavonoids | Flavonoids | [109] | |

| CS | Linun album | Podophyllotoxin | Aryl tetralin-lignans | [112,113] | |

| HR | Linun album | Podophyllotoxin; 6-methoxypodophyllotoxin | Aryl tetralin-lignans | [122,124] | |

| CS | Taxus spp. | Paclitaxel and related taxanes | Diterpene alkaloids | [117,118,119,123] | |

| CS | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [120] | |

| HR | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | Glycosylate triterpenes (Saponins) | [121] | |

| Coro | CS | Corylus avellana | Taxanes | Diterpene alkaloids | [136] |

| CS | Taxus media Taxus globosa | Paclitaxel and related taxanes | Diterpene alkaloids | [131,138] | |

| CS | Linun nodiflorum | 6-Methoxypodophyllotoxin | Aryl tetralin-lignans | [140] | |

| CS | Eschoscholzia californica | Benzo[c]phenanthridine | Alkaloid | [133] | |

| CS | Glicine max | Glyceollins | Isoflavonoid | [134] | |

| Chitosan and chitin | CS | Linun album | Podophyllotoxin | Aryl tetralin-lignans | [112,142] |

| CS | Taxus chinensis Taxus canadiensis | Paclitaxel | Diterpene alkaloids | [143,144,145] | |

| CS | Cistanche deserticola | Phenylethanoid glycoside | Phenylethanoid glycoside | [147] | |

| CS | Vitis vinifera | Stilbenes; trans-resveratrol | Phenylpropanoids | [148] | |

| AR | Morinda citriflora | Total anthraquinones, phenolics and flavonoids | Anthraquinones, phenolics and flavonoids | [149] | |

| CS | Betula platyphilla | Total triterpenoids | Triterpenoids | [151] | |

| HR | Artemisia annua | Artemisinin | Sesquiterpene lactone | [115] | |

| CS | Andrographis paniculata | Flavonoids | Flavonoids | [109] | |

| CS | Psoralea corylifolia Conium maculatum | Psoralen | Furocoumarins | [107,152] | |

| CS | Stephania venosa | Dichentrine | Alkaloid | [85] | |

| Other cell Wall fragments | CS | Dioscorea zingiberensis | Diosgenin | Saponin | [163] |

| CS | Vitis vinifera | Stilbenes; trans-resveratrol | Phenylpropanoids | [148] | |

| AR | Morinda citriflora | Total anthraquinones, phenolics and flavonoids | Anthraquinones, phenolics and flavonoids | [149] | |

| CS | Taxus cuspidata | Paclitaxel | Diterpene alkaloids | [153] |

| Culture System | Plant Species | Secondary Metabolite (SM) | Type of SM | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS, HR | Taxus globosa | Taxanes | Diterpene alkaloid | [138] |

| Morinda citrifolia and Rubia tinctorum | Anthraquinones | Phenolic compounds | [182] | |

| Catharanthus roseus | Vindoline, catharanthine and ajmalicine | Terpenoid indole alkaloids | [183] | |

| Taxus media | Taxanes | Diterpene alkaloid | [55] | |

| Catharanthus roseus | Ajmalicine | Monterpenoid indole alkaloid | [184] | |

| Vitis vinifera | Trans-resveratrol | Stilbenes | [60,185,186,187] | |

| Scutellaria lateriflora | Verbascoside, the flavones: wogonin, baicalein, scutellarein and their respective glucuronides | Phenolic compounds | [188] |

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cusidó, R.M.; Vidal, H.; Gallego, A.; Abdoli, M.; Palazón, J. Biotechnological production of taxanes: A molecular approach. In Recent Advances in Pharmaceutical Sciences III; Muñoz-Torrero, D., Cortés, A., Mariño, E.L., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, India, 2013; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Chauhan, D.; Mehla, K.; Sood, P.; Nair, A. An overview of nutraceuticals: Current scenario. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2010, 1, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonfill, M.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J.; Piñol, M.T.; Morales, C. Influence of auxins on organogenesis and ginsenoside production in Panax ginseng calluses. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002, 68, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, Y.S.; Ogra, R.K.; Koul, K.; Kaul, B.L.; Kapil, R.S. Yew (Taxus spp). A new look on utilization, cultivation and conservation. In Supplement to Cultivation and Utilization of Medicinal Plants; Handa, S.S., Kaul, M.K., Eds.; Regional Research Laboratory: Jammu-Tawi, India, 1996; pp. 443–456. [Google Scholar]

- Alfermann, A.W.; Petersen, M. Natural product formation by plant cell biotechnology. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1995, 43, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.R.; Ravishankar, G.A. Plant cell cultures: Chemical factories of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2002, 20, 101–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Hara, Y.; Suga, C.; Morimoto, T. Production of shikonin derivatives by cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon: II. A new Medium for the production of shikonin derivatives. Plant Cell Rep. 1981, 1, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suffness, M. Taxol: Science and Applications; CRC Press: London, UK; Boca Raton, FL, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 426. [Google Scholar]

- Expósito, O.; Bonfill, M.; Moyano, E.; Onrubia, M.; Mirjalili, M.H.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J. Biotechnological production of taxol and related taxoids: Current state and prospects. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.I.; Pedersen, H.; Chin, C.K. Two stage cultures for the production of berberine in cell suspension cultures of Thalictrum rugosum. J. Biotechnol. 1990, 16, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, K.Y.; Murthy, H.N.; Hahn, E.J.; Zhong, J.J. Large scale culture of ginseng adventitious roots for production of ginsenosides. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2009, 113, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cusido, R.M.; Onrubia, M.; Sabater-Jara, A.B.; Moyano, E.; Bonfill, M.; Goossens, A.; Pedreño, M.A.; Palazon, J. A rational approach to improving the biotechnological production oftaxanes in plant cell cultures of Taxus spp. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J.; Bonfill, M.; Navia-Osorio, A.; Morales, C.; Piñol, M.T. Improved paclitaxel and baccatin III production in suspension cultures of Taxus media. Biotechnol. Prog. 2002, 18, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Cusido, R.M.; Mirjalili, M.H.; Moyano, E.; Palazon, J.; Bonfill, M. Production of the anticancer drug taxol in Taxus baccata suspension cultures: A review. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarzynski, O.; Friting, B. Stimulation of plant natural defenses. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 2001, 324, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Davis, L.C.; Verpoorte, R. Elicitor signal transduction leading to production of plant secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2005, 23, 283–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenas, N.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A. Elicitation: A tool for enriching the bioactive composition of foods. Molecules 2014, 19, 13541–13563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorelick, J.; Bernstein, N. Chapter five—Elicitation: An underutilized tool in the development of medicinal plants as a source of therapeutic secondary metabolites. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 124, pp. 201–230. [Google Scholar]

- Namdeo, A.G. Plant cell elicitation for production of secondary metabolites: A review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2007, 1, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Verpoorte, R.; Contin, A.; Memelink, J. Biotechnology for the production of plant secondary metabolites. Phytochem. Rev. 2002, 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, J.M.; Woffenden, B.J. Plant disease resistance genes: Recent insights and potential applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Brugger, A.; Lamotte, O.; Vandelle, E.; Bourque, S.; Lecorieux, D.; Poinssot, B.; Wendehenne, D.; Pugin, A. Early signaling events induced by elicitors of plant defenses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaunois, B.; Farace, G.; Jeandet, P.; Clement, C.; Baillieul, F.; Doprey, S.; Cordelier, S. Elicitors as alternative strategy to pesticides in grapevine? Current knowledge of their mode of action from controlled conditions to vineyard. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 4837–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebel, J.; Mithoefer, A. Early events in the elicitation of plant defense. Planta 1998, 206, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S. Biological elicitors of plant secondary metabolites: Mode of action and use in the production of nutraceutics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 698, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Jones, J.D. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1773–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zheng, L.P.; Wang, J.W. Nitric oxide elicitation for secondary metabolite production in cultured plant cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.Y.; Im, H.W.; Kim, H.K.; Huh, H. Accumulation of 2,5-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone in suspension cultures of Panax ginseng by a fungal elicitor preparation and a yeast elicitor preparation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 56, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams-Ardakani, M.; Hemmati, S.; Mohagheghzadeh, A. Effect of elicitors on the enhancement of podophyllotoxin biosynthesis in suspension cultures of Linum album. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 13, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sampedro, M.A.; Fernández-Tárrago, J.; Corchete, P. Yeast extract and methyl jasmonate-induced silymarin production in cell cultures of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 119, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebelo, S.A.; Maffei, M.E. Role of early signalling events in plant-insect interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, E.E.; Alméras, E.; Krishnamurthy, V. Jasmonates and related oxylipins in plant responses to pathogenesis and herbivory. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, E.E.; Ryan, C.A. Interplant communication: Airborne methyl jasmonate induces synthesis of proteinase inhibitors in plant leaves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 7713–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppalapati, S.R.; Ayoubi, P.; Weng, H.; Palmer, D.A.; Mitchell, R.E.; Jones, W.; Bender, C.L. The phytotoxin coronatine and methyl jasmonate impact multiple phytohormone pathways in tomato. Plant J. 2005, 42, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischer, H.; Oresic, M.; Seppänen-Laakso, T.; Katajamaa, M.; Lammertyn, F.; Ardiles-Diaz, W.; van Montagu, M.C.; Inzé, D.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.M.; Goossens, A. Gene-to-metabolite networks for terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5614–5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasternack, C.; Hause, B. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 1021–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordaliza, M.; García, P.A.; del Corral, J.M.M.; Castro, M.A.; Gómez-Zurita, M.A. Podophyllotoxin: Distribution, sources, applications and new cytotoxic derivatives. Toxicon 2004, 44, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedows, E.; Hatfield, G.M. An investigation of the antiviral activity of Podophyllum peltatum. J. Nat. Prod. 1982, 45, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres, D.C.; Loike, J.D. Lignans: Chemical, Biological and Clinical Properties; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; Volume 30, pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Van Fürden, B.; Humburg, A.; Fuss, E. Influence of methyl jasmonate on podophyllotoxin and 6-methoxypodophyllotoxin accumulation in Linum album cell suspension cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2005, 24, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionkova, I. Effect of methyl jasmonate on production of ariltetralin lignans in hairy root cultures of Linum tauricum. Pharmacogn. Res. 2009, 1, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yang, D.C. Production of ginseng saponins: Elicitation strategy and signal transductions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 6987–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Hahn, E.J.; Murthy, H.N.; Paek, K.Y. Adventitious root growth and ginsenoside accumulation in Panax ginseng cultures as affected by methyl jasmonate. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazón, J.; Cusidó, R.M.; Bonfill, M.; Mallol, A.; Moyano, E.; Morales, C.; Piñol, M.T. Elicitation of different Panax ginseng transformed root phenotypes for an improved ginsenoside production. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 41, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.B.; Yu, K.W.; Hahn, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Differential responses of anti-oxidants enzymes, lipoxygenase activity, ascorbate content and the production of saponins in tissue cultured root of mountain Panax ginseng C.A. Mayer and Panax quinquefolium L. in bioreactor subjected to methyl jasmonate stress. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Palazón, J.; Mallol, A.; Eibl, R.; Lattenbauer, C.; Cusidó, R.M.; Piñol, M.T. Growth and ginsenoside production in hairy root cultures of Panax ginseng using a novel bioreactor. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Yeung, E.C.; Hahn, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Combined effects of phytohormone, indole-3-butyric acid, and methyl jasmonate on root growth and ginsenoside production in adventitious root cultures of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1789–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Gao, W.; Zuo, B.; Zhang, L.; Huang, L. Effect of methyl jasmonate on the ginsenoside content of Panax ginseng adventitious root cultures and on the genes involved in triterpene biosynthesis. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.T.; Yoo, N.H.; Kim, G.S.; Kim, Y.C.; Bang, K.H.; Hyun, D.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.Y. Stimulation of Rg3 ginsenoside biosynthesis in ginseng hairy roots elicited by methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2013, 112, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.T.; Bang, K.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Hyun, D.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Cha, S.W. Upregulation of ginsenoside and gene expression related to triterpene biosynthesis in ginseng hairy root cultures elicited by methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2009, 98, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, N.T.; Murthy, H.N.; Yu, K.W.; Hahn, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Methyl jasmonate elicitation enhanced synthesis of ginsenoside by cell suspension cultures of Panax ginseng in 5-l balloon type bubble bioreactors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 67, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onrubia, M.; Cusidó, R.M.; Ramirez, K.; Hernández-Vázquez, L.; Moyano, E.; Bonfill, M.; Palazon, J. Bioprocessing of plant in vitro systems for the mass production of pharmaceutically important metabolites: Paclitaxel and its derivatives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yukimune, Y.; Tabata, H.; Higashi, Y.; Hara, Y. Methyl jasmonate induced overproduction of paclitaxel and baccatin III in Taxus cell suspension cultures. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 1129–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentebibel, S.; Moyano, E.; Palazón, J.; Cusidó, R.M.; Bonfill, M.; Eibl, R.; Piñol, M.T. Effects of immobilization by entrapment in alginate and scale-up on paclitaxel and baccatin III production in cell suspension cultures of Taxus baccata. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 89, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabater-Jara, A.B.; Onrubia, M.; Moyano, E.; Bonfill, M.; Palazón, J.; Pedreño, M.A.; Cusidó, R.M. Synergistic effect of cyclodextrins and methyl jasmonate on taxane production in Taxus x media cell cultures. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onrubia, M.; Moyano, E.; Bonfill, M.; Expósito, O.; Palazón, J.; Cusidó, R.M. An approach to the molecular mechanism of methyl jasmonate and vanadyl sulphate elicitation in Taxus baccata cell cultures: The role of txs and bapt gene expression. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 53, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exposito, O.; Syklowska-Baranek, K.; Moyano, E.; Onrubia, M.; Bonfill, M.; Palazon, J.; Cusido, R.M. Metabolic responses of Taxus media transformed cell cultures to the addition of methyl jasmonate. Biotechnol. Prog. 2010, 26, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabater-Jara, A.B.; Tudela, L.R.; López-Pérez, A.J. In vitro culture of Taxus sp.: Strategies to increase cell growth and taxoid production. Phytochem. Rev. 2010, 9, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Lu, B.; Kai, G.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Ding, R.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Chen, W.; et al. Tropane alkaloids production in transgenic Hyoscyamus niger hairy root cultures over-expressing putrescine N-methyltransferase is methyl jasmonate-dependent. Planta 2007, 225, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belchí-Navarro, S.; Almagro, L.; Lijavetzky, D.; Bru, R.; Pedreño, M.A. Enhanced extracellular production of trans-resveratrol in Vitis vinifera suspension cultured cells by using cyclodextrins and methyljasmonate. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyzanowska, J.; Czubacka, A.; Pecio, L.; Przybys, M.; Doroszewska, T.; Stochmal, A.; Oleszek, W. The effects of jasmonic acid and methyl jasmonate on rosmarinic acid production in Mentha × piperita cell suspension cultures. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011, 108, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, M.I.; Kuzeva, S.L.; Pavlov, A.I.; Kovacheva, E.G.; Ilieva, M.P. Elicitation of rosmarinic acid by Lavandula vera MM cell suspension culture with abiotic elicitors. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 23, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala, M.A.; Angarita, M.; Restrepo, J.M.; Caicedo, L.A.; Perea, M. Elicitation with methyl-jasmonate stimulates peruvoside production in cell suspension cultures of Thevetia peruviana. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2009, 46, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.L.; Zhu, X.M.; Shao, J.R.; Wu, Y.M.; Tang, Y.X. Transcriptional response of the catharanthine biosynthesis pathway to methyl jasmonate/nitric oxide elicitation in Catharanthus roseus hairy root culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 88, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfill, M.; Mangas, S.; Moyano, E.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazón, J. Production of centellosides and phytosterols in cell suspension cultures of Centella asiatica. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2010, 104, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.T.; Bang, K.H.; Shin, Y.S.; Lee, M.J.; Jung, S.J.; Hyun, D.Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Seong, N.S.; Cha, S.W.; Hwang, B. Enhanced production of asiaticoside from hairy root cultures of Centella asiatica (L.) Urban elicited by methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, A.; Dixit, V.K. Yield enhancement strategies for artemisinin production by suspension cultures of Artemisia annua. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4609–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, Q.; Hayat, S.; Irfan, M.; Ahmad, A. Effect of exogenous salicylic acid under changing environment: A review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 68, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; van Loon, L.C. Salicylic acid-independent plant defence pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 1999, 4, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, W.E.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dučaiová, Z.; Petruľová, V.; Repčák, M. Salicylic acid regulates secondary metabolites content in leaves of Matricaria chamomilla. Biologia (Bratisl) 2013, 68, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Wu, J.C.; Yuan, Y.J. Salicylic acid-induced taxol production and isopentenyl pyrophosphate biosynthesis in suspension cultures of Taxus chinensis var. mairei. Cell Biol. Int. 2007, 31, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosroushahi, A.Y.; Valizadeh, M.; Ghasempour, A.; Khosrowshahli, M.; Naghdibadi, H.; Dadpour, M.R.; Omidi, Y. Improved Taxol production by combination of inducing factors in suspension cell culture of Taxus baccata. Cell Biol. Int. 2006, 30, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Shang, G.M.; Yuan, Y.J. Effect of magnetic field associated with salicylic acid on taxol production of suspension-cultured Taxus chinensis var. mairei. Huaxue Gongcheng/Chem. Eng. 2006, 34, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, A.; Ghanati, F.; Behmanesh, M.; Mokhtari-Dizaji, M. Ultrasound-potentiated salicylic acid-induced physiological effects and production of taxol in hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cell culture. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2011, 37, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefzadi, M.; Sharifi, M.; Behmanesh, M.; Ghasempour, A.; Moyano, E.; Palazon, J. Salicylic acid improves podophyllotoxin production in cell cultures of Linum album by increasing the expression of genes related with its biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1739–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewari, R.K.; Paek, K.Y. Salicylic acid-induced nitric oxide and ROS generation stimulate ginsenoside accumulation in Panax ginseng roots. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 30, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.B.; Hahn, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid induced oxidative stress and accumulation of phenolics in Panax ginseng bioreactor root suspension cultures. Molecules 2007, 12, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.B.; Yu, K.-W.; Hahn, E.-J.; Paek, K.Y. Methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid elicitation induces ginsenosides accumulation, enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant in suspension culture Panax ginseng roots in bioreactors. Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, G.T.; Park, D.H.; Ryu, H.W.; Hwang, B.; Woo, J.C.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.W. Production of antioxidant compounds by culture of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer hairy roots: I. Enhanced production of secondary metabolite in hairy root cultures by elicitation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2005, 124, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Min, J.Y.; Kim, Y.D.; Kang, Y.M.; Park, D.J.; Jung, H.N.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, M.S. Effects of methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid on the production of bilobalide and ginkgolides in cell cultures of Ginkgo biloba. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2006, 42, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrická, D.; Mišianiková, A.; Henzelyová, J.; Valletta, A.; de Angelis, G.; D’Auria, F.D.; Simonetti, G.; Pasqua, G.; Čellárová, E. Xanthones from roots, hairy roots and cell suspension cultures of selected Hypericum species and their antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.; Zhan, J.C.; Huang, W.D. Effects of ultraviolet C, methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid, alone or in combination, on stilbene biosynthesis in cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015, 122, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanandhan, G.; Arun, M.; Mayavan, S.; Rajesh, M.; Jeyaraj, M.; Dev, G.K.; Manickavasagam, M.; Selvaraj, N.; Ganapathi, A. Optimization of elicitation conditions with methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid to improve the productivity of withanolides in the adventitious root culture of Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 168, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitisripanya, T.; Komaikul, J.; Tawinkan, N.; Atsawinkowit, C.; Putalun, W. Dicentrine production in callus and cell suspension cultures of Stephania venosa. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gadzovska, S.; Maury, S.; Delaunay, A.; Spasenoski, M.; Hagège, D.; Courtois, D.; Joseph, C. The influence of salicylic acid elicitation of shoots, callus, and cell suspension cultures on production of naphtodianthrones and phenylpropanoids in Hypericum perforatum L. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 113, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij, B.; Friedrich, L.; Goy, P.A.; Staub, T.; Kessmann, H.; Ryals, J. 2,6-Dicloroisonicotinic acid-induced resistance to pathogens without the accumulation of salicylic acid. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1995, 8, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durango, D.; Quiñones, W.; Torres, F.; Rosero, Y.; Gil, J.; Echeverri, F. Phytoalexin accumulation in colombian bean varieties and aminosugars as elicitors. Molecules 2002, 7, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.G.; Zhao, Z.J.; Xu, Y.; Qian, X.; Zhong, J.J. Novel chemically synthesized salicylate derivative as an effective elicitor for inducing the biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006, 22, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durango, D.; Pulgarin, N.; Echeverri, F.; Escobar, G.; Quiñones, W. Effect of salicylic acid and structurally related compounds in the accumulation of phytoalexins in cotyledons of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars. Molecules 2013, 18, 10609–10628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, D.L. The efficacy of acibenzolar-S-methyl, an inducer of systemic acquired resistance, against bacterial and fungal diseases of tobacco. Crop Prot. 1999, 18, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisset, M.N.; Faize, M.; Heintz, C.; Cesbron, S.; Chartier, R.; Tharaud, M.; Paulin, J.P. Induced resistance to Erwinia amylovora in apple and pear. Acta Hortic. 2002, 590, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Ruggiero, A. Benzothiadiazole (BTH) activates sterol pathway and affects vitamin D3 metabolism in Solanum malacoxylon cell cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 11, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar]

- Kauss, H.; Franke, R.; Krause, K.; Conrath, U.; Jeblick, W.; Grimmig, B.; Matern, U. Conditioning of parsley (Petroselinum crispum L.) suspension cells increases elicitor-induced incorporation of cell wall phenolics. Plant Physiol. 1993, 102, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, Z.H.; Mujib, A.; Aslam, J.; Hakeem, K.R. In vitro production of secondary metabolites using elicitor in Catharanthus roseus: A case study. In Crop Improvement, New Approaches and Modern Techniques; Hakeem, K.R., Ahmad, P., Ozturk, M., Eds.; Springer Science + Bussines Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 401–419. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, G.J.; Konczb, C. Brassinosteroids and plant steroid hormone signaling. Plant Cell 2002, 14, S97–S110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sasse, J.M. Recent progress in brassinosteroid research. Physiol. Plant. 1997, 100, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, B. Brassinosteroids und Sterole Aus der Euroischen Kulturpflamzen Ornithopus sativus, Paphanus sativus and Secale cereale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Halle, Halle, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, A.; Schneider, B.; Porze, A.; Schmidt, J.; Adam, G. Acyl-conjugated metabolites of brassinosteroids in cell suspension cultures of Ornitopus sativys. Phytochemistry 1999, 41, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Min, J.Y.; Kim, Y.D.; Karigar, C.S.; Kim, S.W.; Goo, G.H.; Choi, M.S. Effect of biotic elicitors on the accumulation of bilobalide and ginkgolides in Ginkgo biloba cell cultures. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 139, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitha, B.C.; Thimmaraju, R.; Bhagyalakshmi, N.; Ravishankar, G.A. Different biotic and abiotic elicitors influence betalain production in hairy root cultures of Beta vulgaris in shake-flask and bioreactor. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Ng, J.; Shi, M.; Wu, S.J. Enhanced secondary metabolite (tanshinone) production of Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots in a novel root-bacteria coculture process. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 77, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rühmann, S.; Pfeiffer, J.; Brunner, P.; Szankowski, I.; Fischer, T.C.; Forkmann, G.; Treutter, D. Induction of stilbene phytoalexins in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) and transgenic stilbene synthase-apple plants (Malus domestica) by a culture filtrate of Aureobasidium pullulans. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.L.; Zou, L.; Zhang, C.Q.; Li, Y.Y.; Peng, L.X.; Xiang, D.B.; Zhao, G. Efficient production of flavonoids in Fagopyrum tataricum hairy root cultures with yeast polysaccharide elicitation and medium renewal process. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2014, 10, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadzovska, S.S.; Tusevski, O.; Maury, S.; Hano, C.; Delaunay, A.; Chabbert, B.; Lamblin, F.; Lainé, E.; Joseph, C.; Hagège, D. Fungal elicitor-mediated enhancement in phenylpropanoid and naphtodianthrone contents of Hypericum perforatum L. cell cultures. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015, 122, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroopa, G.; Anuradha, M.; Pullaiah, T. Elicitation of forskolin in suspension cultures of Coleus forskohlii (willd.) Briq. using elicitors of fungal origin. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 2013, 7, 755–762. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Baig, M.M.V. Biotic elicitor enhanced production of psoralen in suspension cultures of Psoralea corylifolia L. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 21, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Yong, Y.; Dai, C. Effects of endophytic fungal elicitor on two kinds of terpenoids production and physiological indexes in Euphorbia pekinensis suspension cells. J. Med. Plants 2011, 5, 4418–4425. [Google Scholar]

- Mendhulkar, V.D.; Vakil, M.M.A. Chitosan and Aspergillus Niger mediated elicitation of total flavonoids in suspension culture of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees. Int. J. Pharma. Bio. Sci. 2013, 4, 731–740. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi, A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Bisaria, V.S. Fungal Elicitors for Enhanced Production of Secondary Metabolites in Plant Cell Suspension Cultures. In Symbiotic Fungi, Soil Biology; Varma, A., Kharkwal, A.C., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 18, pp. 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Tahsili, J.; Sharifi, M.; Safaie, N.; Esmaeilzadeh-Bahabadi, S.; Behmanesh, M. Induction of lignans and phenolic compounds in cell culture of Linum album by culture filtrate of Fusarium graminearum. J. Plant Interact. 2013, 9, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahabadi, S.E.; Sharifi, M.; Safaie, N.; Murata, J.; Yamagaki, T.; Satake, H. Increased lignan biosynthesis in the suspension cultures of Linum album by fungal extracts. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2011, 5, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahabadi, S.E.; Sharifi, M.; Behmanesh, M.; Safaie, N.; Murata, J.; Araki, R.; Yamagaki, T.; Satake, H. Time-course changes in fungal elicitor-induced lignan synthesis and expression of the relevant genes in cell cultures of Linum album. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roat, C.; Ramawat, K.G. Elicitor-induced accumulation of stilbenes in cell suspension cultures of Cayratia trifolia (L.) Domin. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2009, 3, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putalun, W.; Luealon, W.; De-Eknamkul, W.; Tanaka, H.; Shoyama, Y. Improvement of artemisinin production by chitosan in hairy root cultures of Artemisia annua L. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1143–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Shi, M.; Ng, J.; Wu, J.Y. Elicitor-induced rosmarinic acid accumulation and secondary metabolism enzyme activities in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Plant Sci. 2006, 170, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.J.; Li, C.; Hu, Z.D.; Wu, J.C.; Zeng, A.P. Fungal elicitor-induced cell apoptosis in suspension cultures of Taxus chinensis var. mairei for taxol production. Process Biochem. 2002, 38, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Gong, S.; Guo, Z.G. Effects of different elicitors on 10-deacetylbaccatin III-10-O-acetyltransferase activity and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase content in suspension cultures of Taxus cuspidata cells. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 2010, 18, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badi, H.N.; Abdoosi, V.; Farzin, N. New approach to improve taxol biosynthetic. Trakia J. Sci 2015, 2, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Fungal elicitor induces singlet oxygen generation, ethylene release and saponin synthesis in cultured cells of Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Ding, J.Y.; Zhou, Q.Y.; He, L.; Wang, Z.T. Studies on influence of fungal elicitor on hairy root of Panax ginseng biosynthesis ginseng saponin and biomass. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi 2004, 29, 304–305. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi, A.; Jain, A.; Gupta, N.; Srivastava, A.K.; Bisaria, V.S. Co-culture of arbuscular mycorrhiza-like fungi (Piriformospora indica and Sebacina vermifera) with plant cells of Linum album for enhanced production of podophyllotoxins: A first report. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Tao, W.Y.; Cheng, L. Paclitaxel production using co-culture of Taxus suspension cells and paclitaxel-producing endophytic fungi in a co-bioreactor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 83, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Rajauria, G.; Sahai, V.; Bisaria, V.S. Culture filtrate of root endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica promotes the growth and lignan production of Linum album hairy root cultures. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzagli, L.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Barsottini, M.; Vargas, W.A.; Scala, A.; Mukherjee, P.K. Cerato-platanins: Elicitors and effectors. Plant Sci. 2014, 228, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.S.; Kim, W.; Lee, C.; Oh, C.S. Harpins, multifunctional proteins secreted by gram-negative plant-pathogenic bacteria. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, D.; Kjellbom, P.; Lamb, C.J. Elicitor- and wound induced oxidative cross-linking of a proline-rich plant cell wall. Cell 1992, 70, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.J.; Orlandi, E.W.; Mock, N.M. Harpin, an elicitor of the hypersensitive response in tobacco caused by Erwinia amylovora, elicits active oxygen production in suspension cells. Plant Physiol. 1993, 102, 1341–1344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiler, E.W.; Kutchan, T.M.; Gorba, T.; Brodschelm, W.; Niesel, U.; Bublitz, F. The Pseudomonas phytotoxin coronatine mimics octadecanoid signalling molecules of higher plants. FEBS Lett. 1994, 345, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsir, L.; Schilmiller, A.L.; Staswick, P.E.; He, S.Y.; Howe, G.A. COI1 is a critical component of a receptor for jasmonate and the bacterial virulence factor coronatine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7100–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onrubia, M.; Moyano, E.; Bonfill, M.; Cusidó, R.M.; Goossens, A.; Palazón, J. Coronatine, a more powerful elicitor for inducing taxane biosynthesis in Taxus media cell cultures than methyl jasmonate. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamogami, S.; Kodama, O. Coronatine elicits phytoalexin production in rice leaves (Oryza sativa L.) in the same manner as jasmonic acid. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, G.; von Schrader, T.; Füsslein, M.; Blechert, S.; Kutchan, T.M. Structure-activity relationships of synthetic analogs of jasmonic acid and coronatine on induction of benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloid accumulation in Eschscholzia californica cell cultures. Biol. Chem. 2000, 381, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliegmann, J.; Schüler, G.; Boland, W.; Ebel, J.; Mithöfer, A. The role of octadecanoids and functional mimics in soybean defense responses. Biol. Chem. 2003, 384, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauchli, R.; Boland, W. Indanoyl amino acid conjugates: Tunable elicitors of plant secondary metabolism. Chem. Rec. 2002, 3, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, A.; Imseng, N.; Bonfill, M.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J.; Eibl, R.; Moyano, E. Development of a hazel cell culture-based paclitaxel and baccatin III production process on a benchtop scale. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 195, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onrubia, M. A Molecular Approach to Taxol Biosynthesis. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Estrada, K.; Osuna, L.; Moyano, E.; Bonfill, M.; Tapia, N.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J. Changes in gene transcription and taxane production in elicited cell cultures of Taxus x media and Taxus globosa. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfermann, A.W. Chapter Six. Production of natural products by plant cell and organ cultures. In Annual Plant Reviews, Functions and Biotechnology of Plant Secondary Metabolites; Wink, M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 39, pp. 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Berim, A.; Spring, O.; Conrad, J.; Maitrejean, M.; Boland, W.; Petersen, M. Enhancement of lignan biosynthesis in suspension cultures of Linum nodiflorum by coronalon, indanoyl-isoleucine and methyl jasmonate. Planta 2005, 2, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahabadi, S.E.; Sharifi, M.; Murata, J.; Satake, H. The effect of chitosan and chitin oligomers on gene expression and lignans production in Linum album cell cultures. J. Med. Plants 2014, 13, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.H.; Mei, X.G.; Liu, L.; Yu, L.J. Enhanced paclitaxel production induced by the combination of elicitors in cell suspension cultures of Taxus chinensis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2000, 22, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Xu, H.B. Improved paclitaxel production by in situ extraction and elicitation in cell suspension cultures of Taxus chinensis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2001, 23, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, J.C.; Phisalaphong, M. Oligosaccharides potentiate methyl jasmonate-induced production of paclitaxel in Taxus canadensis. Plant Sci. 2000, 158, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Fevereiro, P.S.; He, G.; Chen, Z. Enhanced paclitaxel productivity and release capacity of Taxus chinensis cell suspension cultures adapted to chitosan. Plant Sci. 2007, 172, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.Y.; Zhou, H.Y.; Cui, X.; Ni, W.; Liu, C.Z. Improvement of phenylethanoid glycosides biosynthesis in Cistanche deserticola cell suspension cultures by chitosan elicitor. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 121, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, M.; Tassoni, A.; Franceschetti, M.; Righetti, L.; Naldrett, M.J.; Bagni, N. Chitosan treatment induces changes of protein expression profile and stilbene distribution in Vitis vinifera cell suspensions. Proteomics 2009, 9, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baque, M.A.; Shiragi, M.H.K.; Lee, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Elicitor effect of chitosan and pectin on the biosynthesis of anthraquinones, phenolics and flavonoids in adventitious root suspension cultures of “Morinda citrifolia” (L.). Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Brasili, E.; Praticò, G.; Marini, F.; Valletta, A.; Capuani, G.; Sciubba, F.; Miccheli, A.; Pasqua, G. A non-targeted metabolomics approach to evaluate the effects of biomass growth and chitosan elicitation on primary and secondary metabolism of Hypericum perforatum in vitro roots. Metabolomics 2014, 10, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Q.; Zhan, Y. Chitosan activates defense responses and triterpenoid production in cell suspension cultures of Betula platyphylla Suk. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 2816–2820. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, P.; Hotti, H.; Rischer, H. Elicitation of furanocoumarins in poison hemlock (Conium maculatum L.) cell culture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015, 123, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachinbana, S.; Muranaka, T.; Itoh, K. Effect of elicitors and a biogenetic precursor on paclitaxel production in cell suspension cultures of Taxus cuspidata var. nana. Pakistan J. Biol. 2007, 10, 2856–2861. [Google Scholar]

- Usov, A. Oligosaccharins a new class of signalling molecules in plants. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1993, 62, 1047–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, E.; Kuchitsu, K.; He, D.Y.; Kouchi, H.; Midoh, N.; Ohtsuki, Y.; Shibuya, N. β-Glucan fragments from the rice blast disease fungus Pyricularia oryzae that elicit phytoalexin biosynthesis in suspension-cultured rice cells. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 817–826. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, S.C.; Aldington, S.; Hetherington, P.R.; Aitken, J. Oligosaccharides as signals and substrates in the plant cell wall. Plant Physiol. 1993, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Keen, N.T.; Wang, M. A receptor on soybean membranes for a fungal elicitor of phytoalexin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 1983, 73, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, S.C. Oligosaccharins as plant growth regulators. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 1994, 60, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cosio, E.G.; Feger, M.; Miller, C.J.; Antelo, L.; Ebel, J. High-affinity binding of fungal β-glucan elicitors to cell membranes of species of the plant family Fabaceae. Planta 1996, 200, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarzynski, O.; Plesse, B.; Joubert, J.M.; Yvin, J.C.; Kopp, M.; Kopp, B.; Fritig, B. Linear β-1,3 glucans are elicitors of defense responses in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Mao, Z.; Lou, J.; Li, Y.; Mou, S.Y.; Lu, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, L. Enhancement of diosgenin production in Dioscorea zingiberensis cell cultures by oligosaccharides from its endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 2011, 16, 10631–10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligang, Z.; Guangzhi, Z.; Shilin, W. Effects of oligosaccharins on pigments of Onasma paniculatum callus. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 1990, 2, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Mou, Y.; Shan, T.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhou, L. Effects of polysaccharide elicitors from endophytic Fusarium oxysporium Dzf17 on growth and diosgenin production in cell suspension culture of Dioscorea zingiberensis. Molecules 2011, 16, 9003–9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Huffaker, A. Endogenous peptide elicitors in higher plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, G.; Moura, D.S.; Stratmann, J.; Ryan, C.A. Production of multiple plant hormones from a single polyprotein precursor. Nature 2001, 411, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.A.; Pearce, G. Systemins: A functionally defined family of peptide signals that regulate defensive genes in Solanaceae species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14577–14580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.Q.; Jiang, H.L.; Li, C.Y. Systemin/Jasmonate-mediated systemic defense signaling in tomato. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degenhardt, D.C.; Refi-Hind, S.; Stratmann, J.W.; Lincoln, D.E. Systemin and jasmonic acid regulate constitutive and herbivore-induced systemic volatile emissions in tomato, Solanum lycopersicum. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 2024–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffaker, A.; Dafoe, N.J.; Schmelz, E.A. ZmPep1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis elicitor peptide 1, regulates maize innate immunity and enhances disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffaker, A.; Ryan, C.A. Endogenous peptide defense signals in Arabidopsis differentially amplify signaling for the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10732–10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi, Y.; Sakagami, Y. Phytosulfokine, sulfated peptides that induce the proliferation of single mesophyll cells of Asparagus officinalis L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 7623–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi, Y.; Takagi, L.; Sakagami, Y. Phytosulfokine-alpha, a sulfated pentapeptide, stimulates the proliferation of rice cells by means of specific high- and low-affinity binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 13357–13362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi, Y.; Sakagami, Y. Characterization of specific binding sites for a mitogenic sulfated peptide, phytosulfokine-alpha, in the plasma-membrane fraction derived from Oryza sativa L. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 262, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Ishise, T.; Shimomura, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Matsubayashi, Y.; Sakagami, Y.; Umetsu, H.; Kamada, H. Effects of phytosulfokine-α on growth and tropane alkaloid production in transformed roots of Atropa belladonna. Plant Growth Regul. 2001, 36, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Gibson, D.M.; Shuler, M.L. Effect of the plant peptide regulator, phytosulfokine-a, on the growth and Taxol production from Taxus sp. suspension cultures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 95, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onrubia, M.; Pollier, J.; Vanden Bossche, R.; Goethals, M.; Gevaert, K.; Moyano, E.; Vidal-Limon, H.; Cusidó, R.M.; Palazón, J.; Goossens, A. Taximin, a conserved plant-specific peptide is involved in the modulation of plant-specialized metabolism. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnasooriya, C.C.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Extraction of phenolic compounds from grapes and their pomace using β-cyclodextrin. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, P.X. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular system for drug delibery: Recent progress and future perspective. Appl. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1215–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.K.; Park, J.S. Solubility enhancers for oral drug delivery. Am. J. Drug Deliv. 2004, 2, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejtli, J.; Szente, L. Elimination of bitter, disgusting tastes of drugs and foods by cyclodextrins. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005, 61, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftsson, T.; Brewster, M.E. Pharmaceutical applications of cyclodextrins. 1. Drug solubilization and stabilization. J. Pharm. Sci. 1996, 85, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perassolo, M.; Smith, M.E.; Giulietti, A.M.; Rodríguez Talou, J. Synergistic effect of methyl jasmonate and cyclodextrins on anthraquinone accumulation in cell suspension cultures of Morinda citrifolia and Rubia tinctorum. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016, 124, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J.; He, S.; Zhang, W.; Yu, R.; Zi, J.; Song, L.; Huang, X. Effects of β-cyclodextrin and methyl jasmonate on the production of vindoline, catharanthine, and ajmalicine in Catharanthus roseus cambial meristematic cell cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7035–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro, L.; Perez, A.J.; Pedreño, M.A. New method to enhance ajmalicine production in Catharanthus roseus cell cultures based on the use of cyclodextrins. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 33, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bru, R.; Sellés, S.; Casado-Vela, J.; Belchí-Navarro, S.; Pedreño, M.A. Modified cyclodextrins are chemically defined glucan inducers of defense responses in grapevine cell cultures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Pérez, F.; Belchí-Navarro, S.; Almagro, L.; Bru, R.; Pedreño, M.A.; Gómez-Ros, L.V. Cytotoxic effect of natural trans-resveratrol obtained from elicited Vitis vinifera cell cultures on three cancer cell lines. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2012, 67, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lijavetzky, D.; Almagro, L.; Belchi-Navarro, S.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Bru, R.; Pedreño, M.A. Synergistic effect of methyljasmonate and cyclodextrin on stilbene biosynthesis pathway gene expression and resveratrol production in Monastrell grapevine cell cultures. BMC Res. Notes 2008, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, Z.; Yang, T.; Nopo-Olazabal, L.; Wu, S.; Ingle, T.; Joshee, N.; Medina-Bolivar, F. Effect of light, methyl jasmonate and cyclodextrin on production of phenolic compounds in hairy root cultures of Scutellaria lateriflora. Phytochemistry 2014, 107, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Kastell, A.; Knorr, D.; Smatanka, I. Exudation: An expanding technique for continuous production and release of secondary metabolites from plant cell suspension and hairy root cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belchi-Navarro, S.; Pedreño, M.A.; Corchete, P. Methyl jasmonate increases silymarin production in Silybum marianum (L.) Gaernt cell cultures treated with β-cyclodextrins. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 33, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramirez-Estrada, K.; Vidal-Limon, H.; Hidalgo, D.; Moyano, E.; Golenioswki, M.; Cusidó, R.M.; Palazon, J. Elicitation, an Effective Strategy for the Biotechnological Production of Bioactive High-Added Value Compounds in Plant Cell Factories. Molecules 2016, 21, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21020182

Ramirez-Estrada K, Vidal-Limon H, Hidalgo D, Moyano E, Golenioswki M, Cusidó RM, Palazon J. Elicitation, an Effective Strategy for the Biotechnological Production of Bioactive High-Added Value Compounds in Plant Cell Factories. Molecules. 2016; 21(2):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21020182

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamirez-Estrada, Karla, Heriberto Vidal-Limon, Diego Hidalgo, Elisabeth Moyano, Marta Golenioswki, Rosa M. Cusidó, and Javier Palazon. 2016. "Elicitation, an Effective Strategy for the Biotechnological Production of Bioactive High-Added Value Compounds in Plant Cell Factories" Molecules 21, no. 2: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21020182