1. Introduction

In the Netherlands, sheltered work companies (sw-companies) have the task to provide jobs to persons that need to work. There are 93 Dutch sw-companies that operate either at the local or regional level. Despite the similar task of providing employment to disabled people, a wide variety of corporate images, slogans, logos and other elements of marketing strategies can be observed. An important explanation for this is the variety of domains in which these sw-companies operate. Firstly, they operate through governmental subsidy for employing a fixed number of disabled people, either within their own facilities or under their guidance and supervision at a regular employer; secondly, sw-companies may perform production work or services for external contractors. Maintenance of public green, dry-cleaning services, or assembling pre-produced bicycles are examples of these activities. In these activities, other subcontractors offering productions facilities or similar services are its most important competitors; thirdly, they get resources by seconding temporary employees to external employers. Here, sw-companies serve as temp agencies which make other temp agencies as their most important competitors; fourthly, it may sell the products that have been made within its own facilities. Other producers offering similar products now are its main competitors; and finally, it offers care to people with severe disabilities. Here, full day care facilities may be considered as competitors of sw-companies and, in fact, in some cases, sheltered work employees and full-care patients may be even found working within the same facility.

These diverse activities are reflected in the marketing activities of sw-companies. For instance, some sw-companies present themselves on their website as “an instrument for municipalities” (for example sw-company LANDER), whereas other companies present themselves more as “a professional and market oriented organization” (for example sw-company Novatec) or “a human development company” (for example SWB Groep) [

1,

2,

3]. These images represent different identities. A company that presents itself as “an instrument for municipalities” obviously wishes to reflect the public identity of a government agency with reliability and trustworthiness as important values. In contrast, a company that presents itself as “a professional and market oriented organization” positions itself clearly as an entrepreneurial partner for businesses. Key values here may be efficiency and innovation. Finally, a company that present itself as a “human development company” calls into mind an idea of care-giving and focusing on the needs and wishes of their client population. Sw-companies use these identities when developing their marketing strategies.

In the remainder of this article, we analyze the marketing of sw-companies more in-depth. We consider marketing as an exchange relation between an organization and its target audiences aimed at achieving specific behavior of these target audiences [

4]. We argue that the marketing of sw-companies is a challenging task because it involves multiple target audiences with different, often ambiguous, values. Analyzing this challenging task may increase the current body of knowledge about the marketing of non-profit organizations. This is important for three reasons. First, although many authors agree that traditional marketing strategies do not work for nonprofit organizations, there is a lack of studies about marketing strategies in specific nonprofit sectors [

5]. This article closely analyzes the marketing in one specific domain: that of sheltered work.

A second reason, and perhaps, theoretically most important: hardly any attention has been paid to the sometimes conflicting and incompatible demands of different target groups and institutional environments in the marketing of non-profit organizations. More so than in the marketing of commercial organizations, focusing on a specific value might estrange other target groups. For example: focusing on the deservingness and special needs of disabled people may undermine employers’ willingness to hire personnel through the sw-company. A theoretical analysis of how sw-companies position themselves amidst these conflicting demands may shed new light on the problems and challenges of the marketing of non-profit organizations in general.

The third reason is concerned with the sw-companies themselves. Because of the continuous austerity measures and disappointing results in the re-integration of disabled people into the regular labor market, the budget for sheltered work in the Netherlands is shrinking. Therefore, sw-companies face an uncertain future with limited financial resources from the government (see [

6]). Therefore, a reorientation of the marketing activities towards more resourceful activities might provide a solution. This analysis of dilemmas and challenges might be helpful in redirecting the marketing activities of sw-companies and may serve as an example for other hybrid organizations. It presents an exploration of marketing in Dutch sheltered work companies based on theory regarding the marketing of non-profit organizations and knowledge of the sector.

The structure of this article is as follows.

Section 2 offers a brief introduction into the marketing of non-profit organizations and hybrid organizations. In

Section 3, we focus on the characteristics of sw-companies and discuss the implications of these characteristics for their marketing strategies and activities.

Section 4 is devoted to the strategic options that sw-companies have concerning their marketing. In the final section, we present conclusions about the marketing challenges of sw-companies and the possibilities to deal with these challenges. Moreover, we will define the theoretical lessons learned from this analysis about the marketing of hybrid organizations. We will also outline a research agenda for the further analysis of marketing strategies of hybrid organizations.

2. The Marketing of Nonprofit Organizations

In this section, we give a brief overview of existing insights in the marketing of non-profit organizations and identify the key issues that may be of importance for our explorative analysis of the marketing of sw-companies. Marketing theories focus on the question “how organizations can behave in relation to their market to help them achieve their goals” ([

7], p. 31). The customers’ needs and wishes are put central in the decision making about marketing.

According to Andreasen and Kotler [

4], the marketing of nonprofit organizations concerns efforts to influence the behavior of target audiences. The target audiences are for example consumers, volunteers and donors. The desired change of behavior is a product of an

exchange between a member of the target audience and the nonprofit organization. This notion that marketing concerns an exchange relationship plays a central role in this article. Members of the target audience are asked to incur costs or to make sacrifices. The nonprofit organization promises benefits in return. In the case of non-profit marketing, these benefits are often abstract and moral in nature. Therefore, we follow Grönroos [

8] who states that marketing can have the function of

giving,

fulfilling and enabling promises to a target group. The concept of promises perfectly captures the nature of the benefits in non-profit marketing. The promises given by organizations in their marketing activities present the benefits to the target audiences if they behave as the organization desires. Through marketing, organizations can make their promises known to their target audiences and stimulate desired behavior.

Various authors claim that nonprofit marketing is different and more complicated than the marketing of profit organizations (see e.g., [

9]; [

10] (based on: [

11]); [

4] (based on [

12])). The most important characteristics that make marketing for nonprofit organizations more complex than for profit organizations are:

- (1).

Non-financial objectives (multiple goals). Non-financial objectives have various difficulties. Firstly, they are often hard to set. Secondly, many of the results of nonprofit organizations are hard to measure because they are outside the organization and often invisible.

- (2).

Public attention, public scrutiny and non-market pressures. Public scrutiny occurs more in a nonprofit context than in a for-profit context. Nonprofit organizations also have to deal with various non-market pressures like political and societal developments. This instability in the context of nonprofits means that they often have even less control over their environment than for-profit organizations.

- (3).

Services and social behavior rather than physical goods. The marketing of services is a more complex process than that of physical goods. Several reasons for this are: services are intangible, heterogeneous and perishable and their production and consumption are inseparable.

- (4).

Multiple public audiences: users and funders. Nonprofit organizations have to deal with multiple target audiences because they do not generate enough income from their customers. In many cases, the customers of the nonprofit organizations are not the funders. Appropriate strategies are harder to develop when an organization has to deal with multiple target audiences.

Particularly, the fourth characteristic of public organizations makes the marketing of these organizations highly complicated. Nonprofit organizations have to give, fulfill and enable promises to a wide range of stakeholders, such as users, funders, policy makers, politicians, citizens and employees. These stakeholders are not only multitudinous, but can also have contrary expectations.

From this section, we conclude that there are several conditions that complicate the marketing of non-profit organizations. In the next section, we will assess to what extent traditional marketing strategies are compatible with these conditions.

3. Marketing Options: Segmentation Strategies and Branding

As we have discussed in the previous section, one of the difficulties in non-profit organizations’ marketing is the differentiated target groups they wish to address. In marketing theory, this is known as different market segments [

4]. In this regard, four strategic choices are possible ([

4], p. 153):

- (1).

Undifferentiated mass marketing: the organization offers a single marketing strategy to the whole market;

- (2).

Differentiated marketing: The organization decides to go after several market segments and develops a specific offer and marketing strategy for each. There are two basic options:

creating fundamentally different offerings for each chosen segment, and

position an existing offering differently to different segments instead of changing it;

- (3).

Concentrated marketing: the organization decides to go after one specific market segment and develops the most ideal offer and marketing strategy for this specific market;

- (4).

Mass customization: the organization customizes the offering to the individual.

Each of these strategies has its own advantages and disadvantages. Treating all target audiences the same has the advantage of achieving economies of scales. Another argument for using this strategy can be the organization’s wish to reach all target groups in its environment. Moreover, it may wish to “speak with one voice” and to prevent confusing the target audiences by giving different signals and mixed messages. However, an important downside is that it never really meets the needs of the target audiences very well because it ignores the diversity of the market [

4]. Andreasen and Kotler ([

4], p. 154) note that in their experience “nonprofit organizations end up making their approaches so bland and general that they don’t speak to anyone. The alternative approach is to cram in so much information and motivations that target audiences are likely to be confused and intimidated”.

Differentiated marketing has the advantage of creating greater responsiveness but it also includes the danger of creating higher costs because the organization has to spend more resources on marketing research and staff training for the different segments [

4]. However, the marketer has the possibility to trade off the higher costs of differentiation. They can do this by reducing the number of segments treated. According to Andreasen and Kotler ([

4], p. 154), the net effect of differentiated marketing is often “that of achieving significantly higher returns for a given budget or a lower budget for given returns”.

Concentrated marketing has the advantage of developing more insight into the specific characteristics of the specific market segment. Cost limits can be achieved through specialization in production, distribution and promotion [

4]. A disadvantage of this strategy is the risk of alienating potentially interesting market segments.

Finally, mass customization has the advantage of meeting the specific needs of each individual member of the target group. However, Andreasen and Kotler [

4] consider it too expensive and impractical for most nonprofit organizations.

The choice of how to target the marketing activities is a first step in developing a market strategy (see [

13]). A second step is positioning the organizations and its products, services or activities in the so-called “marketing mix”. In commercial marketing, the marketing mix is considered to consist of four “p’s”: product, place, promotion and price. In social marketing, three p’s are added to this: “process”, “personnel” and “presentation” [

14,

15]. The seven “p’s” are integrated in the identity, promises and positioning of the non-profit organizations. If a company has many stakeholders, a single, comprehensive message and promise can lead to dilemmas with regard to the marketing mix. The sw-company can, for example, in regard to the “presentation” put much effort in presenting itself as a highly professional organization to help increase its sales and income but this has the risk that it will lead to public scrutiny due to a (too) commercial presentation.

In current marketing literature, the ideas of “branding” have added to the insights from the “seven p’s”. Branding is related to both product and promotion. Brands offer opportunities to differentiate a product or service from competitors’ products and services and can be considered a form of communication with target audiences ([

13], p. 238). Branding contains possibilities for organizations to create the desired image at their target audiences or as Cosgrove ([

16], p. 14) notes: “[brands] put pictures in the heads of the audience targets”. Andreasen and Kotler [

4] note that brands have the potential to reflect an organization’s unique social contribution, the promises to different target audiences and its mission and values. Through a brand an organization can transmit its promises to the different target audiences and in this way generate the desired behaviors. Wymer

et al. ([

17], p. 39–41) subscribe this by stating: “in a real way, a brand is a promise that target publics can count on and trust. It is a promise of what a nonprofit organization stands for, its operational values and integrity, and the promise of the benefit it will deliver to society”.

In carefully developing the image, marketing strategy and brand characteristics, the organization can reflect the desired image it wishes to present to its external environment and target groups. To be efficient, the marketing mix should reflect a coherent and trustworthy image of the organization and its promises. As we have already discussed in the introduction, sw-companies perform many different functions simultaneously and therefore are part of many different institutional environments. This inevitably is reflected in their marketing strategies. For this reason, in the next section, we explore how Dutch sw-companies can deal with the dilemmas of “being many things at the same time” and still develop an adequate marketing strategy.

4. Marketing of Sheltered Work Companies

This section starts by introducing the characteristics of sw-companies in detail. What are their characteristics and in what kind of “worlds” do they operate? After that, we focus on the function of marketing for sw-companies. We then discuss in detail the “exchange relation” for sw-companies: who are the target audiences, what are their desired behaviors and what kinds of promises are expected from the sw-company? As we have already stated in the introduction, the task of Dutch sw-companies is to provide jobs to persons that have to work under adapted circumstances due to their disability. This disability can be a psychological, mental and/or psychical disability. With this task they contribute to the execution of the Sheltered Work Act. Local governments are responsible for good execution of this act and have a great amount of policy freedom (for more details, see for example [

6], 2013).

In total, the Dutch sw-companies offer more than 90,000 jobs to disabled persons. These jobs can be “internal jobs” which are jobs in the sheltered environment of the sw-company itself [

18]. However, these jobs can also be “external jobs” which are at regular employers (for example, supported employment and secondment). In addition to offering jobs as a part of the execution of the Sheltered Work Act, many sw-companies also provide jobs for welfare target groups (for example, welfare recipients and ex-offenders). In 2008, around 65,000 pathways to suitable jobs were offered to these target groups by the Dutch sw-companies [

19]. The type of jobs offered to disabled people by the sw-companies differ [

20]. In the past, there was a great focus on jobs in production activities. Examples of activities were wood working, metal working, packing and printing. Nowadays, sw-companies increasingly focus on service activities for their clients, like cleaning, catering and mail delivery. Various developments contributed to this shift in activities, examples are stringent safety rules, competition from low-wage countries and rapidly changing techniques which make certain activities unsuitable for disabled people. Greening is an activity which has always been important for sw-companies in job provision to disabled people.

Sw-companies can be classified as hybrid organizations as they have both public and private characteristics (see [

18,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]). Characteristic to those organizations is that they have to deal with different values and wishes from their different “environments”: the market, the government and society. They have to deal with public values (e.g., legitimacy, obedience and loyalty), social values (e.g., solidarity, trust and responsibility) and market values (e.g., entrepreneurship, innovation and willingness to take risk). Due to these different environments, sw-companies often have to deal with tensions, conflicting goals and conflicting demands. For instance, if a mentally disabled employee is very productive in the sheltered work facility, he might be able to find a job at a regular employer. However, this raises the question to what extent this is beneficial for the employee himself and for the sw-company. It can be stated that the employee is detached from the safety and supervision of the sheltered work facility, and the sw-company loses a highly productive worker.

In this article, we claim that the ways in which sw-companies position themselves in this dilemma is part of their identity which is reflected in their strategies and marketing activities. The external images they represent are not randomly chosen, but reflect their identity within the hybrid mix of social, governmental and commercial tasks. More specifically, they can use marketing activities to attract funding, attract volunteers, build relationships, communicate, and define their distinctive competencies [

10,

17]. This points us at what we label the “marketing choice imperative”: marketing is a necessary activity for organizations as it provides access to resources and legitimates their existence. However, through marketing activities, organizations also inevitably choose a position in relation to the market, the government and society. Earlier, we defined marketing as an exchange between the organization and a member of a target audience aimed at reaching a change in behavior of that member. This section focuses on how this exchange relation looks like for sw-companies. We discuss how sw-companies perceive their target audiences, what kind of behavior they desire from these target audiences and what they promise in return for their support. This article is based on intensive case studies conducted as a part of a PhD project of one of the authors. This PhD concentrates on the sheltered work companies in the Netherlands. For this case study, interviews have been conducted with directors, policy-makers and other stakeholders in the domain of the social workplaces, and documents have been analyzed.

As we stated earlier, sw-companies have to deal with various target audiences. Just as in many other nonprofit organizations, the funders of sw-companies are not the ones who make use of the facilities of the sw-companies. Municipalities are responsible for funding job facilities for disabled people and (often) do so through sw-companies. This implies that the first two target audiences for marketing activities are municipalities and disabled people. Municipalities can give sw-companies the task to offer jobs to disabled people and let them work as regularly as possible. To fulfill this task, sw-companies have to create jobs for disabled people. These jobs can be internal at the sw-company or external at regular employers. To create internal jobs, sw-companies can produce goods and services for the market. To create external jobs, sw-companies should let employers offer jobs to their clients. Thus, other target audiences are employers and consumers of their goods and services. The final target audience is citizens. Because sw-companies fulfill a social task, mainly financed by tax money, the support of the citizens is also relevant.

Sw-companies perform marketing activities to tempt or stimulate target audiences to perform specific behavior. Municipalities should be tempted to host their disabled citizens in the sw-company’s facility rather than in that of one of its competitors. The desired behavior of employers is that they offer jobs to disabled people. The big challenge in this case is to take away the prejudices of employers towards hiring disabled people. Of the consumers of the produced goods and services, the sw-company wants them to buy their goods and services. This is actually the basic marketing task that for-profit organizations also have to deal with. A challenge in this case is the competition from other companies that provide similar goods and services. The desired behavior of sw-companies for their clients is that they cooperate, which often means that they work as regularly as possible. A challenge in this case is the good conditions of the collective labor agreement (CAO) of sw-companies which makes working for a regular employer unattractive. Another challenge is disabled people’s dislike to change jobs because they are attached to the job they have at the sw-company. In many cases, they have worked there for many years. They are used to the environment and often have strong relationships with their colleagues and the company. This makes accepting a new job unattractive (or even scary) for them. Finally, sw-companies want citizens to support the existence and the policies of the sw-company. This goal is challenged by the old-fashioned image that citizens have of sw-companies and its employees [

29].

Finally, we focus on the question: what does the sw-company have to offer to the target audiences in exchange for their change in behavior? What are the benefits for the target audiences when they behave the way the sw-company desires? First, sw-companies can offer their clients the opportunity to be employees to regular employers. A first benefit for these employers can be that they get good and motivated personnel. However, it can also contribute to their desire to present itself as a socially responsible organization. In that case, it is part of their corporate social responsibility activities (see for example: [

30,

31]). Both benefits can contribute to the profit that the regular employer makes. Second, sw-companies have products and services to offer their customers. The benefits for the customers can be obtaining good products and services but also getting a better feeling about themselves. Third, sw-companies can offer the municipalities jobs for their disabled. The benefit for the municipalities is a good execution of the Sheltered Work Act for which they are responsible. Fourth, sw-companies are organizations with a social task. The benefit for the citizens is that sw-companies contribute to a “better society” by fulfilling their social task. Finally, sw-companies offer disabled people a job. The benefit for disabled people is that having a job can improve their well being. It gives them self-esteem and lets them participate in society.

Table 1 summarizes the different messages that different target groups require. This table clearly shows the complexity of developing marketing strategies for sw-companies.

It is obvious that these different target groups and their specific requirements may conflict. There are three main dilemmas in which these conflicts become most manifest:

- (1).

Presenting disabled people as regular employees or focusing on the corporate social responsibility of employers;

- (2).

Pursuing the ideal of an inclusive society or focusing on the need for segmented care for disabled people;

- (3).

Being competitive in price and quality or being caring and social for disabled employees.

Table 1.

The target audiences, their desired behavior for sw-companies, and benefits.

Table 1.

The target audiences, their desired behavior for sw-companies, and benefits.

| Target audiences | Desired behavior | Challenges for sw-companies to realize this behavior | (Promised) benefits for the target audiences |

|---|

| Regular employers (market) | Giving jobs to disabled people | Convincing employers of the value of disabled people as their employees | Good personnel

Social image |

| Consumers of their goods and services (market) | Buying the goods and services of the sw-company | Competition from other companies that provide these goods and services: differentiate | Good products and services

Good feeling about themselves |

| Local government(s) (government) | Sending their disabled to the sw-company | Competition from other companies where local governments can place their disabled: differentiate | Good execution of the Sheltered Work Act |

Citizens

(society) | Support the existence of sw-companies | Becoming known and get the favorable image | Doing the “right thing” for a better society |

Disabled people (clients)

(society) | Support the existence of sw-companies Work as regular as possible | Collective labor agreement | Improve their well being |

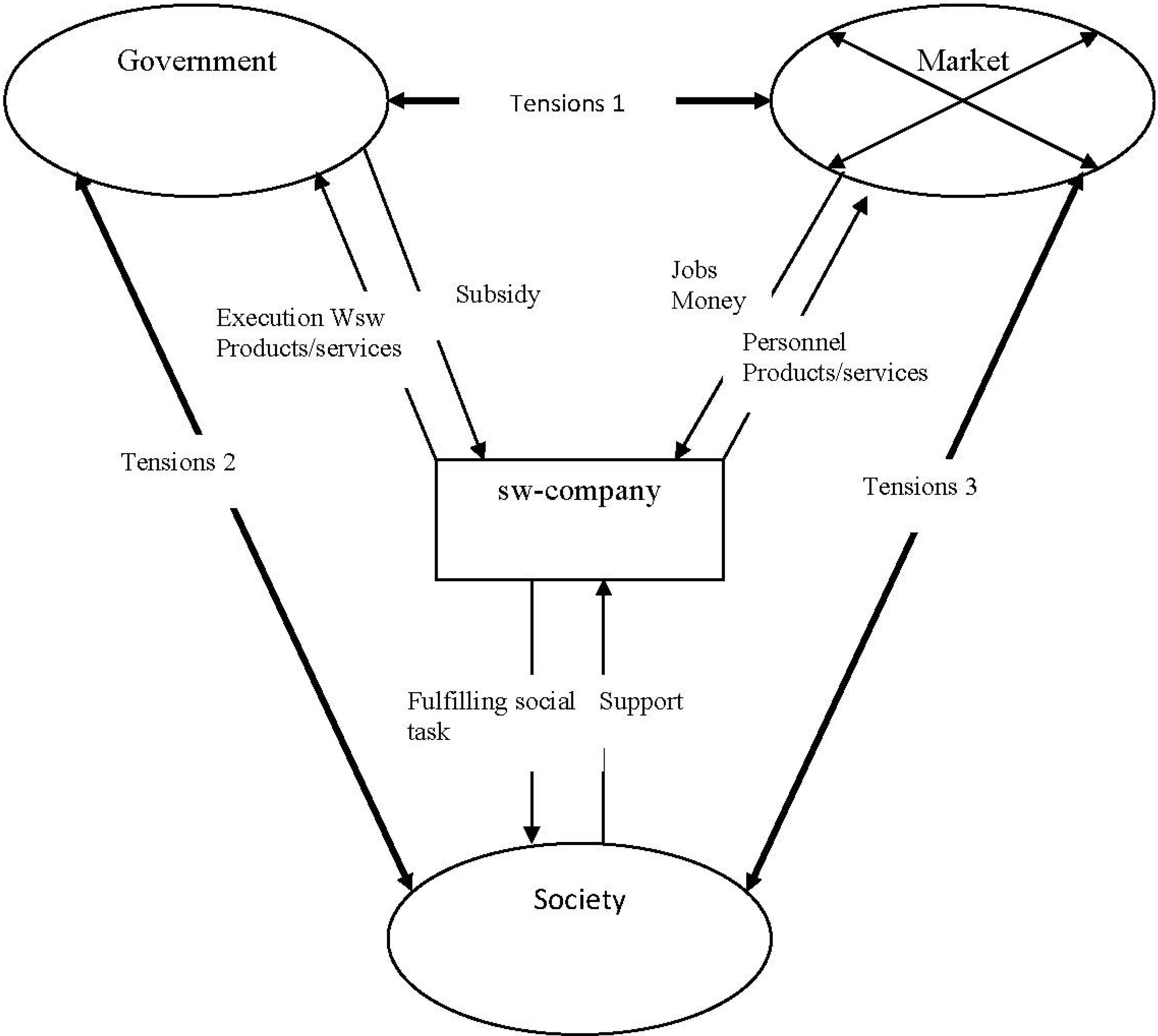

Figure 1.

Marketing of sw-companies: dealing with fragmentation and ambiguity.

Figure 1.

Marketing of sw-companies: dealing with fragmentation and ambiguity.

These three dilemmas have implications for the marketing mix of the seven “p’s” of price, promotion, product, place, process, personnel and presentation. The elements in the marketing mix have to suit the desired behavior of the target group. In this section, we showed that sw-companies have to deal with five target audiences: (1) regular employers; (2) consumers of their goods and services; (3) municipalities; (4) citizens; and (5) disabled people/clients. To realize the desired behavior of these target audiences, sw-companies have to give different “promises”. Therefore, marketing for sw-companies concerns dealing with ambiguity. Ambiguity in the marketing for sw-companies particularly lies in how to “sell” their clients in the market. First, they can present their clients in two opposite ways to get them a job at a regular employer: (1) by emphasizing the strengths and economic value of their clients or (2) by emphasizing the needs of their clients and to address the social feeling of the employer. Second, they can sell their products in two opposite ways: (1) by presenting itself as a “normal” company and to indicate that they offer the best price and quality; and (2) to appeal more to customers’ social feeling and focus on the deservingness of the disabled people who produce these goods and services. So, there are different and opposite ways to try to get the desired behavior from the market parties.

Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the marketing context for sw-companies.

5. Marketing and Branding of Sheltered Work Companies

In the previous section, we looked at marketing for sw-companies. We concluded that the marketing of sw-companies deals with fragmentation and ambiguity. To please all the target audiences, they have to show different promises but these promises can conflict with each other. This section is devoted to the options that sw-companies have in dealing with these challenges. How can sw-companies manage this fragmentation and ambiguity regarding their imaging in an effective way? We focus on different marketing strategies and the possibilities that branding offers. The central question is: what strategies can sw-companies use to unite their different goals/targets in their marketing or branding? Branding is a marketing tool to create the desired image with your target audiences. Sw-companies can show, through their brands, their promise to the different target organizations. When developing marketing strategies, sw-companies have four options (based on the strategic marketing choices presented earlier in this article):

- (1)

develop a brand that is attractive for all target audiences (undifferentiated mass marketing);

- (2)

develop different brands for the different target audiences (differentiated marketing);

- (3)

develop a brand that is attractive for one or just some of the target audiences (concentrated marketing);

- (4)

develop a brand that customizes the offer to the individual (mass customization).

The first option may appear to be the best option but is actually quite hard (if not impossible) to realize. As shown in the previous section, the different target audiences of sw-companies want different and even conflicting promises from the sw-companies. This makes it hard to create a brand that covers all the promises. Sw-companies can try to search for an “overarching promise” but this possesses the risk that none of the target audiences feel themselves really addressed. The option of “developing several brands for the different target audiences” is a rather expensive option because several brands need to be developed. Moreover, it is questionable if the company succeeds in isolating the different target groups and preventing the “wrong” target group receiving the “wrong” message. If this is the case, all efforts of creating differentiated marketing strategies may have been wasted. The third option builds on a concentrated marketing strategy. This alternative has the downside of potentially neglecting some essential target groups. For their survival, sw-companies depend on all, or at least most, target audiences. For example: sw-companies generate 70% of their income from the government and 30% from the market. The fourth option increasingly shows the problems as discussed for Option 2.

Every option has a serious down-side. Sw-companies thus always choose in that sense a non-optimal option. Sw-companies need to be able to give, fulfill and enable promises to five different target groups to steer the desired behavior of these groups. This does not only lead to multiple promises, but also to conflicting ones. The optimal choice of a differentiated, undifferentiated, concentrated and mass customization marketing strategy will differ between the different sw-companies. Sw-companies have to decide which option best suits the environment and goals of the company.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this article was to present an in-depth exploration of the occurrence of marketing in Dutch sheltered work companies based on theory regarding the marketing of non-profit organizations and knowledge of the sector. We looked at marketing as being the efforts to influence the behavior of target audiences in the desired direction, and we presented it as an exchange between target audiences and the sw-company. To generate insights about the marketing of Dutch sheltered workshops, we had to determine what the target groups are, what their desired behavior is and what the sheltered work company has to offer to their target groups.

Table 1 presented an overview of this. We concluded that marketing is a complex activity for sw-companies because organizations have to deal with both fragmentation and ambiguity. The marketing of sw-companies is challenging due to: (1) they need all five target audiences; (2) the “promises” that the target audiences wish from the sw-companies differ; (3) the different “promises” are difficult to integrate or unite (ambiguity).

In this article, we discussed four marketing and branding strategies for sw-companies on how to deal with the different target audiences: undifferentiated, differentiated, concentrated or mass customization marketing/branding. We concluded that all of the options are suboptimal as they all have a serious downside. The downsides are: the risk of connecting to none of your target audiences, high costs, and the risk that some target audiences needed for the realization of the organizations goals are neglected. The analysis in this article also provides useful insights for the marketing of other hybrid organizations like hospitals, schools and housing organizations. We pointed towards the “marketing choice imperative” that occurs due to the need for marketing activities for organizational survival combined with the impossible situation to send a clear and satisfying “promise” to all target audiences. This inevitably creates the danger that hybrid organizations become alienated from one or more necessary target audiences. A great challenge for hybrid organizations is thus to cope with this seemingly impossible situation and to (at least) minimize the negative effects.

A next relevant research step is therefore to look empirically at the marketing of hybrid organizations. From this article, several analytic tools follow that can be used for further research on this topic. When conducting empirical research on the marketing of sw-companies, it is especially worth looking at the content of the “promises” sw-companies make to their target audiences, with a focus on needs and strengths, types of values, and different levels. In addition, it is interesting to investigate how sw-companies position themselves as a public, market-oriented or societal company. Finally, research should be conducted on the chosen undifferentiated, differentiated, concentrated or mass customization marketing and branding strategies of the sw-companies.