Abstract

In Maningrida, northern Australia, code-switching is a commonplace phenomenon within a complex of both longstanding and more recent language practices characterised by high levels of linguistic diversity and multilingualism. Code-switching is observable between local Indigenous languages and is now also widespread between local languages and English and/or Kriol. In this paper, I consider whether general predictions about the nature and functioning of code-switching account for practices in the Maningrida context. I consider: (i) what patterns characterise longstanding code-switching practices between different Australian languages in the region, as opposed to code-switching between an Australian language and Kriol or English? (ii) how do the distinctions observable align with general predictions and constraints from dominant theoretical frameworks? Need we look beyond these factors to explain the patterns? Results indicate that general predictions, including the effects of typological congruence, account for many observable tendencies in the data. However, other factors, such as constraints exerted by local ideologies of multilingualism and linguistic purism, as well as shifting socio-interactional goals, may help account for certain distinct patterns in the Maningrida data.

1. Introduction

In Maningrida, northern Australia, code-switching—the practice of using more than one language within a conversation or clause—is a commonplace phenomenon within a complex of both longstanding and more recent multilingual practices. Fourteen Indigenous languages representing four language families are spoken among 2500 people, alongside increasing use of English and contact varieties such as Kriol, an English-lexified creole spoken across northern Australia (Meakins 2014). Individual linguistic repertoires are typically large, but strong ideologies exist dictating rights and responsibilities around language ownership and use. A variety of language mixing practices is observable between local traditional languages, and is now also widespread between local languages and English and/or Kriol. Code-switching is an established feature of the longstanding ‘egalitarian’ multilingual ecology of the region (Singer and Harris 2016; Vaughan and Singer 2018), yet the practice is also symptomatic of a changing local language ecology, shaped by the large-scale incursion of English and implicated in the emergence of a local urban mixed variety.

In this paper, I consider whether general predictions about the nature and functioning of code-switching account for practices in the Maningrida context, and for patterns attested across the diverse multilingual contexts of northern Australia more generally. I consider: (i) what patterns characterise longstanding code-switching practices between different traditional languages in the region, as opposed to newer code-switching between a traditional language and Kriol or English. What (if any) generalisations can be made? Additionally, (ii) how do the observable distinctions align with general predictions and constraints from dominant theoretical frameworks, or by the typological congruence of the languages implicated? Need we look beyond these factors to explain the patterns? Data from this context present an opportunity to test structural constraints theories and to explore the impact of social-psychological pressures of divergence and convergence in cultural and linguistic practice.

The data relied upon in this paper is drawn from a corpus of conversational data and participant observation gathered by the author through collaborative research in Maningrida since 2014. The broader corpus contains over 100 h of data privileging naturalistic interaction from a range of public and private domains, linguistic biography interviews and language drawings, ethnographic notes and additional language data elicited using stimulus materials. Data is coded for the languages used and relevant metadata. A targeted subset of the data is also fully transcribed and translated (approximately 10 h). A large subsection of the corpus is accessible through the Endangered Languages Archive.1 Permission has been given for the inclusion of all data featured in this paper. A small amount of supplementary data draws on earlier work in the region and is attributed accordingly.

2. Code-Switching

Code-switching refers to a form of multilingual discourse where a single speaker employs more than one language within a conversation (e.g., Auer 1998; Muysken 2000). In some cases, multiple languages are used within individual clauses. Code-switches are in some ways similar to what are known as borrowings, but the two differ in important ways (which is not to say that the boundary between them is always entirely clear). A borrowing is generally understood to be a linguistic pattern or item from one language that, as a result of language contact, has become fully incorporated into another language, morphosyntactically and often phonologically (e.g., Poplack 1993). Code-switches, on the other hand, are not typically integrated in the same way, and are more momentary interactional choices that do not form part of the core lexicon or system of the ‘host’ language. Borrowings will not be addressed in this paper but are certainly an important outcome of language contact with relevance to many issues discussed here. See, for example, Dixon (1970), Heath (1981), Black (1997) and Bowern and Atkinson (2012) for discussions of borrowings in Australian languages.

A brief note should be made about code-switching terminology, which varies considerably across the literature. In this paper, I rely on the following terms and definitions (e.g., following, Muysken 2000, p. 3):

- −

- intrasentential code-switching: switching between languages inside the level of the clause. This type encompasses:

- −

- insertional code-switching: the insertion of elements from one language into the matrix of another language

- −

- alternational code-switching: switching between the grammatical structures of more than one language

- −

- intersentential code-switching: switching that occurs outside the level of the clause.

2.1. Constraints and Motivations in Code-Switching

Work on code-switching can be loosely grouped into two categories. On the one hand, there are what might be referred to as ‘grammatical’ or ‘structural’ accounts—i.e., approaches which are interested in examining the interaction of the grammatical features of the contributing languages and in understanding how these contribute to and shape the resultant code-switching patterns. On the other hand, ‘social’ or ‘functional’ accounts are those more interested in understanding the social and discourse motivations which organise multilingual conversation and interaction. Typically, although not exclusively, intrasentential (i.e., insertional and alternational) switches have been examined through the lens of grammatical accounts, while intersentential switches have been subject to investigations of their social and discourse functions. Some research has, of course, drawn together investigations of both grammatical and social aspects, and important contributions to major developments in the field have emerged from work in both areas. In this section, I briefly overview key insights and general predictions about the shape and functioning of code-switching to emerge from this work in order to ascertain to what extent these account for tendencies in the Maningrida data.

Grammatical accounts are necessarily more relevant where code-switching within the clause is concerned—in these scenarios, two or more grammatical systems are brought into contact. Various theories exist concerning structural constraints on code-switching, some of which have been proposed to apply universally to all languages in mixed constructions. I do not propose to exhaustively consider all dominant theoretical frameworks in grammatical accounts of code-switching here, but three key assumptions are of particular relevance to the switching which will be described in the following sections. They relate to the relative ‘dominance’ of contributing languages in mixed constructions (the Matrix Language Frame and ‘4-M’ models (e.g., Myers-Scotton 1993; Myers-Scotton and Jake 2000)), the sites of switching from one language to another (the free morpheme and equivalence constraints (e.g., Pfaff 1979; Poplack 1980)), and the effect of congruence between structures in the contributing languages on the shape and ‘ease’ of code-switching (e.g., Myers-Scotton 1993, 1995; Poplack 1980; Weinreich 1964). These assumptions have shaped seminal work on code-switching constraints and expectations in the field about the nature of multilingual data we might expect to observe.

Myers-Scotton’s Matrix Language Frame model and the associated ‘4-M’ model (e.g., Myers-Scotton 1993; Myers-Scotton and Jake 2000) have been particularly influential in constraint-based theories. This model assumes that one language in (intrasentential) code-switching can be considered the ‘matrix’, that is the more dominant language which provides a grammatical frame into which elements from another language (the ‘embedded’ language) can be inserted. Various techniques have been posited to determine the matrix language in any given case—such as the language of the verb and the overall morpheme count from each language—but it seems that no one set of criteria is suitable for all languages (Muysken 2000, p. 68). Myers-Scotton’s theory predicts that the matrix language provides the word and/or morpheme order for the clause as a whole. The model further contrasts content morphemes (those which assign or receive thematic roles, e.g., nouns and verbs) with system morphemes (those which do not, e.g., function words and inflectional morphology). The category of system morphemes splits further into ‘early’ system morphemes—which contain essential conceptual structure for conveying speaker intentions and depend on their head for further information (e.g., plural marking, determiners)—and ‘late’ system morphemes which indicate relationships in the mapping of conceptual structure onto phrase structures. These late system morphemes are further divided into subcategories, one of which—‘outsider’ late system morphemes—functions to make the relationships between elements in the clause more transparent (e.g., case, tense and aspect morphology). The 4-M model adds that the matrix language should necessarily contribute specific types of morphemes—namely, those of the outsider late system morpheme type. When system morphemes do come from the embedded language, Myers-Scotton asserts that they should appear as embedded language islands (e.g., formulaic expressions, time, manner and quantifier expressions, agent NPs) (Myers-Scotton 1993).

Another influential contribution relates to the nature of ‘switch points’—the sites within clauses at which code-switching is licensed or most readily facilitated. Poplack’s ‘free morpheme constraint’ (e.g., Poplack 1980) posits that switching may occur after any constituent, but not between a free morpheme and a bound morpheme (however see, e.g., González-Vilbazo and López 2011 for examples of word-internal code-switching, providing counter-examples to this constraint)2. The ‘equivalence constraint’ (e.g., Pfaff 1979; Poplack 1980) predicts that code-switching tends to occur where the surface structure of the contributing languages map onto each other.

A third key prediction, related to the equivalence constraint, has to do with the typological congruence of the contributing languages. Various scholars have posited the notion that congruence between structures in two languages would be expected to facilitate code-switching (e.g., Myers-Scotton 1993, 1995; Poplack 1980; Weinreich 1964) and for others this idea is assumed even if not explicitly stated (e.g., Joshi 1985). Congruence is generally taken to mean an equivalence of categories across languages, such as similar syntactic functions and semantic properties for grammatical categories, or categories perceived to be phonologically similar (e.g., Clyne 1987). The upshot here is that intrasentential code-switching ought to be somehow ‘easier’ between linguistically congruent languages which may share similar features through shared inheritance and/or diffusion3. (e.g., Clyne 1967, 1980, 2003) notes the ‘triggering’ potential of heteroglossic forms, i.e., the potential for words with similar form or meaning to encourage code-switching. Conversely, constraints are understood to arise from a lack of congruence between the contributing languages, with code-switching potentially ‘blocked’ by these factors. Although ample counter-evidence from code-switching between typologically different languages certainly exists (see, e.g., Chan 2009 for an overview), “these original constraints have not faded away in the current literature” (Chan 2009, p. 184). Furthermore, Sebba (1998) proposes that congruence is not simply a property of the syntax of the contributing languages, but is rather something ‘created’ by bi/multilinguals finding common ground between languages. Since congruence is located in the minds of speakers, the nature of community bilingualism in any given case is highly relevant. Congruence may, therefore, be forged by such factors as social relations between groups and the extent and time-depth of bilingualism. This discussion of theories of structural constraints is by no means exhaustive; several others continue to exert considerable influence—see, e.g., Meakins (2011, pp. 92–95, 122–28) for an overview.

Social, pragmatic and discourse accounts have generally been assumed to provide insights into the broader motivations for code-switching, to explore the factors at work in determining whether code-switching occurs at all and which codes are drawn upon when it does. Foundational work in the area has considered how the choice of code is influenced by the local situation or domain, often referred to as ‘situational code-switching’ (e.g., Blom and Gumperz 1972; Fishman 1972; Gumperz 1982), by some aspect of the speaker’s or interlocutor’s social identity or the social meanings indexed by the code itself, (‘metaphorical’ code-switching) (e.g., Gumperz 1982; Myers-Scotton 1993), and by changes in the discourse, such as to signal a change in topic or a quotation (‘conversational code-switching’) (e.g., Auer 1998; Li Wei 2005). Since his early work in northern Australia, (e.g., McConvell 1988) has pressed the importance of looking beyond purely linguistic factors when attempting to explain code-switching behaviours and to consider all cases within the framework of social theories. He is critical, however, of the compulsion in social accounts to construct strict dichotomies of code-switching, warning that this tendency frequently leads to confusion (with each scholar dividing social factors up differently), and further cautions against probabilistic accounts which correlate code choices with fixed social determinants in the local environment. Instead, he espouses a more direct approach to the meanings of switches which transcends these dichotomies, engaging with the more open question of ‘why’ code-switching occurs (and not just ‘how’ and ‘when’). Importantly for the discussion of the Maningrida data to follow, McConvell highlights the central importance of basing analyses of code-switching on the specific local systems of social formations, language ecologies and ideologies rather than assuming any predetermined structures. In this sense, a comprehensive and nuanced analysis depends crucially on ethnographically informed understandings of the social role of each code, for a given individual, and in a given situation.

Following Pfaff (1979, p. 291) and Backus (2003, p. 246), Meakins (2011, p. 122) asserts that although “social theories may offer explanations for the broader motivations of code-switching such as reasons for the practice itself and the choice of matrix language, structural constraints theories provide more information about the resultant shape of the code-switching”. In the discussion below, I draw on both approaches to gain as full a picture as possible of the pressures and motivations acting on code-switching in the Maningrida context. This will involve considering whether general predictions from dominant structural-constraints theories account for the data. A key question that will be addressed is to what extent, if any, social and ideological factors influence the ‘resultant shape’ of code-switching in this context, as well as the motivations behind it.

2.2. Code-Switching in the Australian Context

Although a substantial body of work exists documenting post-colonial and contemporary code-switching practices in northern Australia especially, this research has focused almost exclusively on switching between a traditional language and English or Kriol (Hamilton-Holloway, forthcoming and McConvell 1988 provide rare overviews of code-switching in the Indigenous Australian context more generally). Loose tendencies have been observed in switching between these varieties: drawing together earlier work (e.g., Bani 1976; Day 1983; Dixon 1980; Haviland 1982; Lee 1983; Leeding 1993), McConvell (1988, 2002) describes a standardised style of socially ‘unmarked’ code-switching which has emerged in many contexts across northern Australia (or at least not so obviously socially marked as switching between traditional languages), especially where morphologically complex languages of the non-Pama-Nyungan group are spoken alongside more recent arrivals. In this mixing style, the tendency is to draw on the traditional language as the matrix, retaining verbal morphology from that language, and to adopt nominal features and other vocabulary from English or Kriol. Mansfield (2016) and McConvell (2002) further note the strategy—widespread in contact scenarios in the region—of using light verbs (which may have co-existed with non-compound verb forms in the traditional language) as a ‘welcoming’ environment for accommodating English or Kriol verbal material. A representative example from Modern Tiwi is given below (Tiwi elements bolded).

wokapat a-mpi-jiki-mi with layt walk she-NPST-DUR-do with light ‘She is walking with a light’ Modern Tiwi (McConvell 2002, p. 336)

Mushin’s (2010) work on switching between Garrwa (Gulf of Carpentaria, N.T.) and Aboriginal English/Kriol considers the practice broadly from the perspective of a Conversation Analysis approach (e.g., Sacks et al. 1974). She identifies various discourse motivations for switches, including to repair communication breakdown, to reflect a shift in (conversational) activity, and to organise a narrative. Similarly, McConvell’s (1994) account of switching between Gurindji and Kriol in a monologic narrative notes the use of Gurindji for the narrative itself, with Kriol drawn on for meta-textual commentary.

Seminal research on mixed languages has emerged from the documentation of Australian languages in recent decades. Mixed languages are the result of fusion of both lexical and structural elements from two languages, such that the resulting stable variety cannot be said to have just one single linguistic ancestor (e.g., Matras and Bakker 2003). Code-switching is often centrally implicated in this process (e.g., Auer 1999; Thomason 2003) and, hence, this work has provided valuable insights into both the shape of code-switching in Australian Indigenous communities as well as the role of these practices in the emergence of contact varieties. Gurindji Kriol and Light Warlpiri are two important Australian examples which illustrate the social nature of language genesis, and which demonstrate how code-switching practices in one generation may contribute to a more stabilised variety in the next. In the case of Gurindji Kriol, spoken in the Victoria River District of northern Australia, code-switching between Gurindji dialects and Kriol among Gurindji people in the 1970s shaped the eventual structures of the mixed language which emerged in tandem with the Gurindji workers’ rights and land rights movements of that era (Meakins 2008b). Within the contemporary Gurindji language ecology, code-switching still occurs between (traditional) Gurindji and Kriol, as well as now between Gurindji Kriol and its source languages and the practice is not viewed as “a sign of linguistic weakness” but rather as promoting a multilingual identity (Meakins 2008a, p. 298). In the case of Light Warlpiri, a mixed language from Lajamanu in Central Australia, child-directed speech in one generation incorporated code-switching between Warlpiri and Aboriginal English/Kriol. In the subsequent generation, the children who had received this code-switched input conventionalised, expanded and innovated on these structures and the mixed language Light Warlpiri emerged (O’Shannessy 2012). Since the emergence of this new variety, it has come to index membership in a ‘young Lajamanu Warlpiri’ community of practice (O’Shannessy 2015; cf. Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2007).

Although it is claimed by some that code-switching between traditional languages occurs frequently (e.g., McConvell 1988, p. 113), accounts are rare. Where the practice is mentioned, descriptions are typically brief and general, often found in introductory sections or as a footnote in a grammar. It is unclear whether this points to the practice being less commonly attested, or whether it is simply that researchers were not interested in it or failed to notice it. A small set of notable exceptions exist. Mixing between traditional languages for ceremonial, narrative or ‘aesthetic’ purposes is explored in Evans’ (2010) work on polyglot narratives and in O’Keeffe’s (2016) doctoral thesis on dance-song repertoires, both focused on western Arnhem Land. Earlier examples are noted in Strehlow (1971) and Wilkins (1989) for central Australia, and in Hercus (1990) for northern South Australia. Mixing for complex social purposes is exemplified in McConvell’s (1985, 1988) work on code-switching between Gurindji dialects (Victoria River region, N.T.). Bradley (1988) describes the use of different Yanyuwa dialects (Gulf of Carpentaria, N.T.) for teasing purposes, and other local cases of mixing are noted in Rumsey (2018) (northern Kimberley, W.A.), Sutton (1978) and Haviland (1982) (both Cape York, QLD), and Pensalfini (2003) (Barkly Tableland, N.T.). The practice of receptive multilingualism, whereby each interlocutor maintains their own distinct language in an interaction, is explored in Singer and Harris’ (2016) work on multilingualism at Warruwi (western Arnhem).

Although there is only a small body of transcribed text to examine, some observable tendencies emerge in the characteristics of code-switching associated with mixing between traditional languages. One has to do with the contexts in which this mixing is most commonly observed: very often these contexts are socially or stylistically ‘marked’ in some way, for example performative storytelling, song registers, and special speech styles such as teasing. As McConvell (1988) notes, switching between traditional varieties may be seen as largely ‘stylistic’—used to express meanings about social situations, but not in any deterministic way. Another tendency has to do with the shape of the code-switching: switching between traditional languages appears to be more commonly of the intersentential type, that is with switching occurring outside the level of the clause. Some notable exceptions do exist, however, for example the insertional code-switching observed in the performative manipulation of Bininj Kunwok dialects in the narrative profiled in Evans (2010), and in data provided in Pensalfini (2003) and Hamilton-Holloway (forthcoming) which shows the insertion of bound discourse markers and transitive subjects in mixing between Jingulu, Mudburra and Eastern Ngumpin.

3. Multilingualism in Maningrida

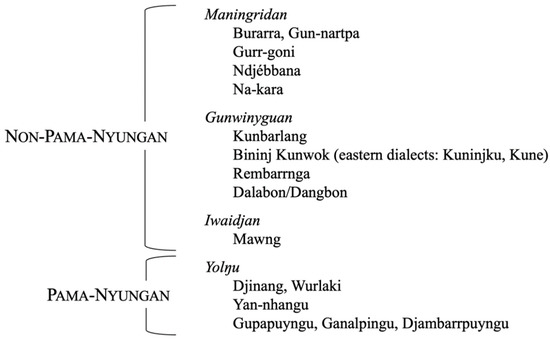

On Australia’s north-central coast, about halfway along the coastline of the Indigenous-owned region of Arnhem Land, the community of Maningrida sits at the mouth of the Liverpool River. Maningrida was founded in the late 1950s as a welfare settlement and now serves as a regional hub for some 2500 people who connect with a diverse range of language and cultural groups from the Maningrida region and further afield in Arnhem Land. Local language repertoires are highly multilingual (e.g., Elwell 1977; Handelsmann 1996; Vaughan and Carter, forthcoming), with typical repertoires (especially of older people) taking in several traditional languages, varieties of Englishes, Kriol, and alternate sign language systems. Over a dozen traditional languages are attested in regular use (although to different extents) in the local space, with this local linguistic diversity mirroring diversity in traditional social and cultural life. Unusually for the region, there is no shared spoken language that functions as a lingua franca or communilect across all local groups in Maningrida: “the social need for a spoken lingua franca does not seem to exist” (Elwell 1977, p. 119). Figure 1 depicts the geographical homelands of these traditional varieties, while Figure 2 shows their genetic groupings across four language families and across the major boundary between Pama-Nyungan (typically dependent-marking and suffixing) and Non-Pama-Nyungan languages (typically head-marking and prefixing) (e.g., Koch 2014). For languages on both sides of this boundary, word order is not fixed but rather wholly or partially pragmatically based.

Figure 1.

The Maningrida (Manayingkarírra) region, showing traditional language groups in red and associated territory (Map: Brenda Thornley4).

Figure 2.

Genetic groupings of the traditional languages of the Maningrida region5.

As is the case in many parts of Indigenous Australia, the traditional languages of the Maningrida region are ideologised as inherently bounded and primordially connected to specific tracts of land (Merlan 1981). These connections between language and land have real effects, with individuals understood to be the ‘owners’ of a language through their membership of a particular land-owning clan group, with associated rights and responsibilities inherited through their paternal line. As such, the primary linguistic affiliation is typically with the father’s language, the ‘patrilect’, with secondary affiliations to languages associated with other kin (e.g., mother, grandparents). The guiding principles of traditional multilingualism largely still in operation in Maningrida are delineated succinctly in Sutton’s (1997, p. 240) key ‘propositions’ of Indigenous multilingualism (reiterated with further additions in Evans 2010, p. 277). I reproduce them here—slightly edited—as a useful touchstone for understanding key ideologies behind contemporary language choices in the Maningrida context.

- Languages are owned, not merely spoken. They are inherited property.

- Languages belong to specific places, and the people of those places.

- Use of a particular language implies knowledge of, and connectedness to, a certain set of people in a certain part of the country.

- Languages are ‘natural phenomena’ of mythic origin. They are relational symbols, connecting those who are different in a wider set of those who are the same, all having totems and languages. This variety itself is part of the common condition.

- At the local level, such differences are internal to society, not markers of the edges of different societies.

- The ancestors moved about and spoke different languages, and this is how people still do or should live today.

- It is important, not accidental or trivial, that we speak different languages. The heroic ancestors knew that cultural differences made for social complementarity, in a world where cultural sameness alone could not prevent deadly conflict. There is no balance without complementarity. There is no complementarity without distinctions and differences.

- The existence of multiple languages enriches the texture and beauty of life, and particularly of verbal art.

- Polyglot mastery suggested breadth of ceremonial contacts and far-flung social capital.

Although actual language use and competence may not align precisely with ideologies around language ownership (e.g., through life circumstances an individual may not have had the opportunity to learn their father’s language), these principles nevertheless exert substantial pressure over language choices and lived experience. Speakers’ connections with traditional varieties have largely endured, producing an unusually resilient multilingual ecology akin to ‘egalitarian’ or ‘small-scale’ multilingualisms described elsewhere in the world (e.g., François 2012; Lüpke 2016; Singer and Harris 2016; Vaughan and Singer 2018)—these are systems where many languages are spoken by relatively small groups of people who are multilingual in each other’s languages, and where the interaction of different languages is not ‘polyglossic’ (i.e., determined by domain or a strict social hierarchy (e.g., Fishman 1967)).

Multilingual interactions are commonplace in Maningrida; both public and private discourse frequently contain more than one language. Elwell’s early work (Elwell 1977, 1982) on Maningrida multilingualism amply illustrates the diversity of codes drawn on in single interactions. Elwell observed various community settings, including the local shop and school, and found a wide range of languages in daily use. At the shop, for example, she tracked the code-choices of both the shopkeeper and his customers across 37 different exchanges. Of the 34 exchanges involving the shopkeeper, Tommy Wokbara, only 6 were in his first language only (Ndjébbana, the traditional language of the land where Maningrida sits). The rest drew on other languages in his linguistic repertoire—Kunwinjku, Kunbarlang, Mawng, Na-kara, Burarra and English—or combined more than one of these within the interaction. Codes were deployed strategically in response to knowledge of the interlocutors’ repertoires and choices were sensitive to a variety of socio-interactional factors, such as the nature of the interaction (e.g., asking a favour) and the relationship between the interlocutors (e.g., observance of brother–sister taboo). One interaction employed receptive multilingualism, five involved code-switching of various kinds, and the remainder were monolingual, although no transcripts were provided to enable further study (see Elwell (1977, pp. 98–103, 202–8) for full details). Across both the shop and the school contexts investigated, Elwell found that knowing the composition of individual linguistic repertoires was not sufficient to predict which language would be used in any given interaction. More recent work on multilingualism in Maningrida has shown that intense and resilient multilingualism endures in the community, albeit with some changes observable in the local language ecology such as the increased use of Kriol6, the diminishing use of certain traditional languages (e.g., Yan-nhangu and Kunbarlang), and the emergence of a mixed urban variety of the Burarra language. This latter development reflects a process of ‘linguistic urbanisation’—a process referring to the explosion of new ‘ways of speaking’ amid the shift to urban communities across northern Australia (Mansfield 2014)—in which young speakers are central (Vaughan and Carter, forthcoming). Vaughan (2018b, 2020) profiles public and semi-private interactions at the local school, at the church, at a football match, and in more domestic settings and finds a similar diversity of languages in frequent use as in Elwell’s work: numerous traditional languages, English, and more recently emergent contact varieties. Significant differences are observable across interactional settings, with ‘hybrid spaces’—those shaped by the interaction of diverse groups, institutions and ways of speaking—particularly conducive to the emergence of new kinds of language practices (Vaughan 2018b).

4. Code-Switching in Maningrida

Code-switching of various kinds is characteristic of Arnhem Land’s longstanding ‘egalitarian’ multilingual ecology (Singer and Harris 2016; Vaughan and Singer 2018), but the practice is also symptomatic of recent changes to the local ‘shifting langscape’ (Angelo 2006) following the large-scale incursion of English and the subsequent development of contact varieties. In the following sections I consider both of these categories of code-switching in turn, first providing a description of mixing between traditional linguistic varieties (both of the inter- and intrasentential types) (Section 4.1), and then turning to mixing which recruits traditional languages, local English varieties and/or Kriol (Section 4.2). In Section 4.3 and Section 4.4, I explore the range of linguistic constraints and social pressures which influence the shape and functioning of code-switching in the Maningrida context.

4.1. Code-Switching between Traditional Languages

As noted in Section 2.2, in-depth descriptions of code-switching between traditional Australian Indigenous languages are scarce. The Maningrida context is no exception, with the only significant mention of the practice found in Elwell’s (1977, 1982) work on community multilingualism (Section 3), where code-switching was a strategy employed in a minority of the exchanges featured. Elsewhere, general references have been made to the practice and to high levels of multilingualism to be found in the area (e.g., Harvey 2011; McConvell 1988; Meakins 2011), but most of these also rely on Elwell’s account or on Handelsmann’s (1996) survey of support needed for the community’s languages (which surveyed speaker numbers rather than specific multilingual practices). I endeavour to contribute to redressing this imbalance by here describing a small set of examples of traditional language code-switching from (predominantly) the last decade in Maningrida. I separate out intersentential switching from intrasentential switching because, as we will see, these practices are quite distinct in frequency, form, social meaning, and in the contexts in which they are most readily observed.

4.1.1. Intersentential Switching between Traditional Languages

Code-switching between traditional languages where switches occur outside the level of the clause or sentence is relatively commonplace in Maningrida, especially in discourse occurring in more public domains. The following four observed examples give a sense of some different scenarios where this kind of mixing typically occurs.

Example 1.

A senior Djinang man is conducting a lesson for young students in his role as a language and culture teacher at the local school. The small assembled group of students are predominantly Burarra children with just a couple of Djinang students present. The Djinang teacher is a senior knowledge holder of cultural information, including about Djinang bush medicine, and a fluent speaker of both Djinang and Burarra (although Djinang is his patrilect). He begins his short lesson by speaking about bush medicine for about a minute in Djinang. He then switches to Burarra for the rest of the lesson and uses Burarra to frame occasional key terms in Djinang.

Example 2.

The same Djinang man is leading a re-enactment of the Stations of the Cross as part of Good Friday celebrations at the church. He draws on Djinang, Burarra and English when welcoming the worshippers, introducing the event and in the subsequent (unscripted) re-enactment (see Vaughan 2020 for further discussion). In this particular example, his talk is performative and broadcast to a general audience rather than targeted to a specific interlocutor:

(2.1) yaw lim-buŋi-ban Jesus lim-buŋi-ban Jesus! yes 1pl-hit-tf 1pl-hit-tf DJINANG nguburr-bu barra nguburr-bu barra! 12a-hit fut 12a-hit fut BURARRA ‘We’re hitting Jesus, we’re hitting Jesus!

We’re going to hit him, we’re going to hit him!’[ELAR deposit 0488: burarra_lects078]

Example 3.

At the football Grand Final in 2014, a small group of men from different language groups (Burarra, Ndjébbana and Yolngu Matha) are commentating on the play and communicating with the crowd using a microphone and speakers set up on the back of a flatbed truck. One of the Yolngu Matha men, who also uses Burarra on a daily basis, commentates in both Yolngu Matha and Burarra and then switches to Ndjébbana to berate a section of the crowd—supporters of the typically Ndjébbana-speaking Hawks team.

Example 4.

A Na-kara woman is tasked with recording a ‘cultural warning’7for the website of a linguistic archive. Although Na-kara is her patrilect, she is more comfortable in Ndjébbana and does not use Na-kara as a daily language. She is accompanied by an Ndjébbana woman who has higher fluency in Na-kara than she does and who is assisting with the recording. They discuss and plan the recording in Ndjébbana, and then switch to Na-kara for the recording’s content.

In each of these examples, the choice of code reflects a tension between several pressures:

- (i).

- Audience design (e.g., Bell 2001)—shaping the message to cater to the linguistic repertoires of the interlocutor(s). In example 1, for instance, Djinang man Stanley draws on Burarra in acknowledgement of the repertoires of the predominantly Burarra audience, while in example 3 the Yolngu commentator switches into Ndjébbana when targeting his message to the Hawks supporters.

- (ii).

- Social and cultural identity—where the speaker has a personal connection to a code and is compelled to use it (as in Sutton’s key ‘propositions’ (Sutton 1997) (Section 3)). This is relevant in example 4 where the woman for whom Na-kara is the ideologically prescribed language is expected to use it rather than the woman who speaks the language fluently (but is not patrilineally connected to it). This pressure also plays out when a code is appropriate for a particular topic, as in example 1 where Djinang is the ‘right’ language to discuss Djinang bush medicine.

- (iii).

- Linguistic competence—where a speaker is more comfortable in one code than in another, as in the use of Ndjébbana by the Na-kara woman in example 4. In example 2, there is some redundancy in the sematic content with the Burarra clauses largely repeating the message of the Djinang clauses. However, in cases like these, I would argue that code-switches serve to build semiotic complexity into composite utterances (following Carew 2016, p. 134)—in cases like these “when encountering multiple signs which are presented together, take them as one” (Enfield 2009, p. 6). As in these examples, it is often the case that intersentential switching between traditional languages in Maningrida serves relatively clearly discernible interactional goals.

Receptive multilingualism is not usually considered to be a form of code-switching as receptive multilingualism does not refer to the use of multiple languages by one speaker, but rather to the use of one language per interlocutor in an interaction. However, as a closely related practice the use of receptive multilingualism in Maningrida bears mentioning here. For example, there are married couples in the community who are known to me and for whom this mode of communication is the norm at home (e.g., one person using Burarra and the other Kuninjku), but I have not closely documented these practices (see Singer 2018 for an account of this practice among a married couple not far afield at Warruwi, north-western Arnhem Land).

4.1.2. Intrasentential Switching between Traditional Languages

Code-switching between traditional languages that occurs inside the level of the clause is much less common than intersentential switching, and is typically quite situationally restricted8. It is also the case that code boundaries are frequently blurred in possible examples. Nevertheless, a small number of cases are to be found in the corpus. In the following three examples there are particular features of the local interaction or the social identity of the speaker which contribute to the choice of switching.

Example 5.

An Elder of the Kunibídji group (the landowners of Maningrida), whose patrilect is Ndjébbana, is seated outside her home with three other women: a senior Burarra woman, a young Na-kara woman, and an Anglo-Celtic English speaker (the author). We had been discussing local child-rearing practices, with the Kunibídji Elder using Ndjébbana and English. In this example, she also draws on Burarra, partly to address her question to the Burarra woman (and likely the Na-kara woman, who also speaks Burarra), but also in response to a topic shift. Both the Burarra and the Na-kara women understand Ndjébbana, so the switch is not strictly necessary for their comprehension.

(5.1) and an-guna an-nga jay barra-ngúddjeya ‘babbúya’? i-prox i-what att 1a-say ironwood ENGLISH BURARRA NDJÉBBANA ‘And what’s that, hey, that they (Burarra people) say for ‘ironwood”? [ELAR deposit 0488: burarra_lects085]

The Burarra woman responds to her question in Burarra: (‘Jarlawurra? Ngardichala?’ (‘Leaves? Ironwood?’)).

Example 6.

In a domestic exchange witnessed by linguist Margaret Carew during a recent fieldtrip, a Gun-nartpa man is among a family group encompassing speakers of Gun-nartpa and Djambarrpuyngu. His sister-in-law, to whom he is culturally expected to perform respect, earlier brought a fish to the house. He makes the following statement as part of an exchange in Gun-nartpa, drawing on the Djambarrpuyngu noun in deference to his sister-in-law’s main language:

(6.1) guya ana-ga-nyja. fish 3i.to-take-rls DJAMBARRPUYNGU GUN-NARTPA ‘She brought a fish.’ (Fieldnotes 2017, M. Carew)

Example 7.

A Yan-nhangu woman recounts a narrative about her past to linguist Beulah Lowe. The recording was made at Milingimbi, an Arnhem Land community east of Maningrida. The exact date is unknown but her granddaughter, who shared the recording with me, estimates it to be the 1970s. This text is unusual for the high frequency of insertional and alternational (as well as intersentential) code-switching between Yan-nhangu and Burarra, for example:

(7.1) nyirriny-barra nyirriny-ninya dina gun-gapa arrinyjila exc.ua.f-eat exc..ua.f-be.pc dinner iv-dist 12ua.f.dat BURARRA jorrnyjurra ngaja higher.ground indeed.f BURARRA marn.gi nhuma ‘jorrnyjurra’? knowledge 2pl higher.ground BURARRA YAN-NHANGU BURARRA nhakun ‘hill’ like YAN-NHANGU ENGLISH […] tape an-ngunyjuta nyiburr-balaki-ja nyiburr-workiya i-prox.opp exc.a-send-c exc.a-do.always.c ENGLISH BURARRA gunarda ana-gorrburrwa janguny iv.dem 2a.dat story BURARRA manymak good YAN-NHANGU ‘We were eating dinner, that one for us. Higher up, indeed. Do you know that ‘jorrnyjurra’? Like ‘hill’. […] These tape recordings we’re always sending—that one there, that story is for you all. Good.’ [ELDP deposit 0488: burarra_lects025]

I suggest that the comparatively high and sustained levels of mixing here, unusual in the Maningrida context for mixing between traditional varieties, is a linguistic reflex of a hybrid ‘Yan-nhangu-Burarra’ identity which, in contemporary times, is now largely expressed through the Burarra language (as very few speakers now have fluent command of Yan-nhangu). Speakers who align with this identity category connect to traditional homelands from the mouth of the Blyth River east to the Crocodile Islands. ‘Yan-nhangu-Burarra’ is enumerated among the Burarra cultural subgroups and even as a Burarra dialect label by some speakers. It is plausible that in situations of very close bilingualism, where both languages index connections to important land and clan groups, this kind of code-switching might more readily arise.

4.2. Code-Switching between Traditional Languages and English and/or Kriol

McConvell notes the emergence across northern Australia of a standardised style of ‘unmarked’ code-switching (McConvell 2002, p. 337) between Non-Pama-Nyungan prefixing languages and English and/or Kriol (Section 2.2). This is broadly speaking also true of the Maningrida context, with patterns of intrasentential switching also predominantly, although not exclusively, reflecting the regional tendency whereby the traditional language functions as the matrix, with English and/or Kriol contributing nominal-related features and vocabulary. As we will see, the familiar pattern (Mansfield 2016; McConvell 2002) of using light verbs as a strategy for incorporating ‘foreign’ verbal material is also in operation here. Intersentential mixing between traditional languages and English is also fairly widely attested, although as Elwell (1977, p. 100) notes, stretches of English talk between Indigenous interlocutors is usually dispreferred outside of western institutional settings in Maningrida.

As Hamilton-Holloway (forthcoming) notes, looking at the relative frequencies of different code-switching patterns might provide more insight than focusing only on the occurrence/non-occurrence of different types. To this end, a comparison of code-switching types in the Good Friday data (introduced in Section 4.1) gives a small window into which strategies are most commonly drawn upon. Of the 154 clauses/short utterances transcribed from this event, 59% were in a single code (and were not followed by a switch to another code), 21% involved insertional code-switching, 7% involved alternational code-switching, and another 7% involved an intersentential switch after the clause. A breakdown of the specific languages used is given in Table 1:

Table 1.

A breakdown of code-switching types in the Good Friday text (burarra_lects078).

Among the code-switched examples here, the higher frequency of switching between traditional languages and English (especially Burarra-English) is notable, and there is only a single case of intrasentential switching between traditional languages only. Given the nature of the data, however—that is to say a small corpus of public, often broadcast and highly performative language use—this cannot provide a full picture of code-switching more generally, especially as these practices vary significantly across different social contexts. For example, the high levels of English use here (as the only language in a clause) is in part to do with the church context which draws significantly on English in its characteristic discourse, while the relatively high levels of Kuninjku and Burarra/Gun-nartpa in part reflect the language demographics of the church attendees and the status of these languages as common L2s in Maningrida.

The following examples show mixing between Burarra and English, between English, Burarra and Yolŋu languages, and between English and Ndjébbana. Burarra-English mixing is a particularly interesting case as it appears to be implicated in the emergence of a mixed variety (Carew 2017, forthcoming), or rather a translingual ‘style’ (in the sense of, e.g., Eckert 2008). This ‘Maningrida Burarra style’ (Vaughan and Carter, forthcoming) is not currently the primary code of any speaker but rather is associated with particular domains (such as ‘hybrid’ spaces), interactional types and indexical values. In this way, although it is still the case that no true lingua franca has ever emerged at Maningrida, this style functions as a kind of ‘multilingua franca’ (Makoni and Pennycook 2012, p. 447) in some contexts—a mode of communication which draws on a multilayered chain of features in adaptation to different moments (Vaughan 2018b).

Example 8.

A senior Gun-nartpa woman is giving a short speech at the local school to launch a book featuring the stories of her clan group, An-nguliny. She is describing the compilation of the book with linguist Margaret Carew, and draws features from her main language, Gun-nartpa—a dialect of Burarra—and from English. Mixing here is less constrained and much more extensive than intrasentential mixing between traditional languages, which in examples 5 and 6 above mark a rare single moment within a longer, largely monolingual text. This is a fairly typical example of ‘Maningrida Burarra style’. Burarra/Gun-nartpa lexical stock is underlined.

- (8.1)

- Jina-bona1999, collecting the stories. Gu-manga janguny, gu-gurtuwurra gu-manga from elders, aburr-ngaypa tribe, Gun-nartpa people. Collecting jiny-ni stories, pictures mu-manga. […] But it’s good for our young generation, so grow up aburr-ni barra mbi-na barra who they family. Then, ngaypa half way ngu-gortkurrchinga. 2014 nguna-manga nyirriny-bona mun-gata last finish mu-ni m-bamana this book.

‘She came in 1999, collecting the stories. She collected stories, gathered and collected them from elders, my tribe—Gun-nartpa people. She collected stories, and took pictures. […] But it’s good for our young generation, so when they grow up they will see that book, see who their family is. Then, half way through I came on board. In 2014 she came and got me and we finished off this book.’[ELDP deposit 0488: burarra_lects077]

Example 9.

At the 2014 football Grand Final between local teams Hawks and Baru, several commentators from different language groups address the crowd (as in Example 3). In this utterance, a Yolngu man speaks to the crowd as a whole, reminding them about the food on offer at the game:

| (9.1) | Don’t forget there’s going to be so many | ngatha | balaji |

| food | food | ||

| YOLŊU MATHA | BURARRA | ||

| ‘Don’t forget there’s going to be so much food’ | |||

In the next extract, also from the Grand Final, a Burarra man is attempting to control the Baru supporters following some tensions after the game. Most local teams have an association with regional clan groups and, by extension, with broader identity categories such as language groups. Baru is traditionally a Burarra team and the team name, the Yolngu word for ‘crocodile’, refers to a clan totem for some Burarra people. Burarra is, therefore, likely to be understood by a majority of supporters:

| (9.2) | Good | afternoon | ||||||||||||

| ENGLISH | ||||||||||||||

| if | jal | nyiburr-ni | mari | |||||||||||

| desire | exc.a-be | trouble | ||||||||||||

| ENGLISH | BURARRA | |||||||||||||

| stop | buburr-ninya | right now | gurdiya | |||||||||||

| exc.a-be | iv.foc.emph | |||||||||||||

| ENGLISH | BURARRA | ENGLISH | BURARRA | |||||||||||

| rrapa | starting up | nyibi-ne-nga | nyiburr-ni-rra | mari | ||||||||||

| and | exc.a:3-cause-im | exc.a-be-c | trouble | |||||||||||

| BURARRA | ENGLISH | BURARRA | ||||||||||||

| no trophy | rrapa | no medal | rrapa | no supporting | ||||||||||

| and | and | |||||||||||||

| ENGLISH | BURARRA | ENGLISH | BURARRA | |||||||||||

| rrapa | no more game | |||||||||||||

| and | ||||||||||||||

| BURARRA | ENGLISH | |||||||||||||

| if right now stop | nyiburr-ni | barra | gun-mola | |||||||||||

| exc.a-be | fut | good | ||||||||||||

| ENGLISH | BURARRA | |||||||||||||

‘Good afternoon. Unless you want trouble, stop that right now. And causing trouble means no trophy, and no medals, and no supporting, and no more game. If you all stop right now, it’ll be OK.’[ELDP deposit 0488: burarra_lects075]

Example 10.

Here, the Kunibídji Elder introduced in Example 5, whose patrilect is Ndjébbana, is speaking about her experiences as a grandmother helping raise her grandchildren. In this utterance, she switches from English to Burarra and Ndjébbana for direct reported speech, one of the few examples of code-switching used to structure narrative identified in the corpus.

(10.1) But I was holding that baby and I was telling her “nya djíya” take.2sg dem.m BURARRA NDJÉBBANA ‘But I was holding that baby and I was telling her, “here, take him”’. [ELDP deposit 0488: burarra_lects085]

4.3. Linguistic and Typological Effects in Code-Switching

Code-switching in Maningrida recruits over a dozen languages, and it is evident that the grammatical structures of the contributing codes play a central role in determining the shape of the resulting switching. Here, I revisit three key predictions from the literature about how intrasentential code-switching is expected to be constrained by linguistic factors (Section 2.1) and consider to what extent these align with code-switching in the Maningrida region. It should be acknowledged that the small set of data presented here is limited in its capacity to fully interrogate the applicability of these frameworks to the diversity of mixing in the Maningrida context—this would necessitate a more in-depth exploration of how each constraint accounts for mixing in a much larger corpus. Nevertheless, the data do provide some insight into potential challenges to these influential models and constraints. As suggested in the literature, it does not seem that linguistic/typological factors exert any significant pressure on intersentential code-switching.

- (i).

- Myers-Scotton’s Matrix Language Frame and 4-M models

In the small corpus interrogated here, Myers-Scotton’s assumption that one language functions as the matrix into which material from the other language(s) is embedded is broadly borne out. For example, in example 7, Yan-nhangu material is embedded in a Burarra matrix, and not the other way around. It is not the case that in language pairs one language takes on the matrix role across all situations, but recent iterations of the Matrix Language Frame model do not predict this, so this is not taken as evidence that the data here contradicts the current model. For example, in Burarra–English mixing, examples 6 and 9.2 show Burarra in use as the matrix, while example 8 shows a predominantly Burarra matrix with an occasional switch to English (but a clear preference for Burarra verbal and English nominal material). In the examples of Ndjébbana-English mixing, an Ndjébbana matrix is used in 5, while 10 shows an English matrix. Therefore, McConvell’s (2002) observation that traditional languages in northern Australia tend to function as the matrix is therefore only partially borne out here. Myers-Scotton’s predictions regarding content vs. system morphemes are broadly supported by the data. Although system morphemes such as demonstratives and plural marking from English are used within a Burarra matrix (e.g., example 8), since these are considered ‘early’ and not ‘outsider late’ system morphemes this does not contradict the model’s predictions (e.g., Myers-Scotton and Jake 2017). Furthermore, several of these morphemes in example 8 may be considered part of embedded language islands which are in any case understood to be able to carry outsider late system morphemes from the embedded language10.

- (ii).

- Switch points

Poplack’s ‘free morpheme constraint’, stipulating that switching cannot occur between a free morpheme and its bound morpheme, is not challenged by the data here. Like Meakins (2011, p. 123) notes for Gurindji–Kriol mixing, relying on the linear equivalence of elements to determine switch sites (the ‘equivalence constraint’) is inappropriate for mixing involving languages with wholly or partially pragmatically based word order (as is the case for Maningrida languages).

- (iii).

- Typological congruence

Typological congruence (and likely also congruence resulting from long-term diffusion) between languages certainly has an effect on the resultant shape of code-switching in Maningrida, but not to the extent predicted by dominant theories in the literature. Where this factor does appear to have an effect is in the emergence and prevalence of certain grammatical constructions in local traditional languages which facilitate the incorporation of material from English and Kriol (especially Burarra, which as we have seen is the most common target for switching with English, in large part due to ‘Maningrida Burarra style’). These strategies are necessary due to ‘incongruence’ between traditional languages and the newer arrivals, and especially the challenge of code-switching within morphologically complex words. Two examples from Burarra (also noted in Carew 2017) are the rise of light verbs—which have long been part of the language’s grammar—as a welcoming environment for English and Kriol verbal material (as seen in example 8 and repeated below, allowing incorporation of collecting and grow up), and the emergence of the locational post-position ginda (the contracted form of gu-gu-yinda (loc.iv-der-do.thus)) to incorporate switched nouns which would otherwise need a nominal prefix to express locational information (11).

(8.1) Collecting jiny-ni stories pictures 3ii-be ENGLISH BURARRA ENGLISH mu-manga […] 3:3iii-get.pc BURARRA so grow up aburr-ni barra 3a-be fut ENGLISH BURARRA ENGLISH mbi-na barra who they family 3a:3iii-see fut BURARRA ENGLISH ‘She collected stories, and took pictures […] so when they grow up they will see that book, see who their family is’. [ELDP deposit 0488: burarra_lects077]

(11) A: Mun-werranga wartpirricha ee iii-different yam.sp yes BURARRA B: Gipa mu-rrima-nga murda gipa mu-rrima-nga already 3iii-hold-rls iii.foc already 3iii-hold-rls BURARRA Book ginda mu-yu-rra <gu-gu-yinda

loc.iv-der+do.thus3iii-lie-c ENGLISH BURARRA ‘She already has that one, she already has it. It’s in the book.’ (Carew 2017, p. 226)

Yet, despite the grammatical ‘challenge’ of incorporating English or Kriol material in a traditional language matrix and the suggestion in the literature that intrasentential code-switching ought to be somehow ‘easier’ between traditional languages due to their closer congruence, we have seen that mixing between traditional languages below the level of the clause is much less frequent and much more constrained than mixing between traditional languages and English or Kriol. As noted in Section 2.1, of course this paper is not the first to question the universality of the equivalence constraint and of restrictions imposed on code-switching by typological congruence (Chan 2009), but the discussion of the data here is intended to provide further weight to these existing challenges. The following section considers possible reasons (beyond the purely linguistic) why these patterns might have emerged in the Maningrida context.

4.4. Social-Psychological, Ideological and Discourse Effects in Code-Switching

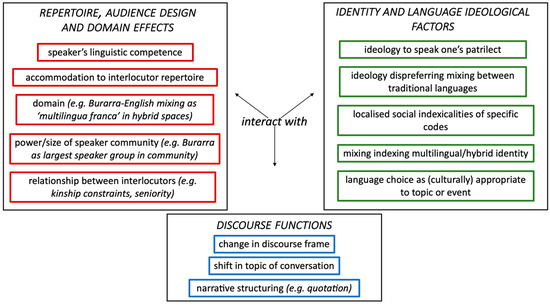

In this section, I respond to claims that, while social theories can reveal motivations behind the occurrence of code-switching, it is structural constraints theories that help explain the specific linguistic characteristics of the practice (e.g., Backus 2003; Meakins 2011; Pfaff 1979). I argue that although typological and other linguistic facts are certainly central to understanding the characteristics of code-switching in Maningrida, social factors do in fact exert significant pressure on its resultant shape as well as its functions. To this end, I outline the most salient social-psychological, ideological and discourse effects acting on local code-switching practices to have emerged from analysis of the data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Social and pragmatic pressures on code-switching in Maningrida.

The composition of speaker and interlocutor repertoires unsurprisingly contributes significantly to language choice across the community, with code-switching often reflecting a compromise or a meeting-point between the two (e.g., example 1). A kind of audience design is also at play in situations where language choice reflects some aspect of the speaker-interlocutor relationship, such as performance of respect for certain kinship pairs. However, as Elwell (1977) observed, this factor alone was not sufficient to predict which codes would be drawn on in any given interaction. The role of linguistic competence is particularly noticeable when the language the speaker is most comfortable in is not the ideologically prescribed lect (example 4, cf. discussion of Sutton (1997) in Section 3). The choice of English in interactions, including as a contributor to code-switching, is often a result of audience design even though English is rarely a first language in the community—as Djinang man Stanley Rankin explained to me, English is useful for communicating across diverse speaker groups and is a good choice “because English is new, just came in”, but that he also needed to use Burarra features because “some [kids] don’t really understand” English. Although in Maningrida the domain of interaction has a less central role than has been found in studies of code-switching elsewhere (e.g., Fishman 1972), there is a clear divide between patterns of code-switching in western-dominated and hybrid spaces, such as at the school and the football, and elsewhere. In these spaces, a large number of languages are drawn upon in response to the linguistic diversity of the audience, and Burarra–English mixing as part of Maningrida Burarra style has emerged as a widespread strategy for communication here. Furthermore, Burarra is frequently drawn upon as an L2 across the community reflecting the fact that Burarra people make up the largest local speaker group.

Local language ideologies are major drivers behind code choice in the Maningrida context, although—as is the nature of ideologies—these influence but do not determine behaviours, and often sit in tension with other ideologies. Key language ideologies in the region derive from the fundamental connection between language and territory (Merlan 1981; Sutton 1997) and are centrally implicated in the perseverance of small-scale multilingualism in the region (Section 3). We have seen several examples of the pressure to perform use of one’s patrilect (e.g., examples 1, 2, and 4), and have also seen how the cultural, ideological and ontological connections between clan, country and language can, in some quite specific contexts, have reflexes in intra-sentential code-switching between traditional languages. Illustrations of this include the hybrid ‘Yan-nhangu-Burarra’ identity exemplified in 7.1, the polyglot narratives presented in Evans (2010), and perhaps also the Jingulu-Mudburra switching born of long-term close contact between those groups (Pensalfini 2003; Pensalfini and Meakins 2019) (Section 2.2). In other settings, however, ideologies are in operation which prohibit or at least disapprove of mixing between traditional languages, through a kind of linguistic purism which can prioritise the perceived distinction between codes. This is evident in the metalinguistic policing of ‘appropriate’ traditional language use and boundary maintenance between languages which is particularly notable in commentary from local Elders. Vaughan (2020) gives the examples of young people being chastised for using the ‘wrong’ language or dialectal variants, individuals being mocked for ‘trying’ to speak a language not theirs (even if they have high levels of competence in it), and the attribution of traditional language mixing to drunken behaviour. In Woolard’s (2008) terms, traditional languages might be ontologically positioned as ‘languages from somewhere’—strongly indexical of territory, clan and other cultural touchstones (reflecting Sutton’s (1997) key propositions), which restricts the ways they can be recruited in mixing—while English is locally construed as a ‘language from nowhere’ and, therefore, is able to be drawn on more freely in this practice.

The discourse functions of code-switching in the Maningrida context have only been superficially addressed here. Three examples show use of the practice to structure talk: in example 4, Ndjébbana is used to shift the discourse frame for meta-textual commentary about a core text in Na-kara (akin to McConvell 1994), in example 5 switching in part flags a topic switch in the conversation, and in example 10 the switch marks reported speech. The list of factors identified here is by no means exhaustive and, as Mushin’s (2010) work shows, there are doubtless many more discourse functions served by code-switching to be discovered and other local factors that further ethnographic work might reveal.

Returning to the question of how social factors might impact the shape of code-switching, I have endeavoured to show that although typological factors might be expected to facilitate intrasentential switching between traditional languages, in fact this practice is strongly constrained by the local operation of language ideologies. These ideologies guide speakers to maintain (and even police) boundaries between traditional languages in metalinguistic commentary and in practice, and to adhere to their patrilect in many contexts. Conversely, mixing between traditional languages (especially Burarra) and English or Kriol serves an important function in community discourse and is not restricted in the same way by traditional ideologies. However, as has been noted, in some specific contexts such as in expressing a longstanding hybrid identity or in aesthetic performance, intrasentential mixing between traditional languages is licensed and even celebrated.

Following McConvell’s (1988) perspective, I have been wary of attempting to fit this analysis of instances of code-switching into strict dichotomies and deterministic categories. Any given case of code-switching is likely to be influenced by multiple interacting pressures, the balance of which is affected by shifting nuances of the local interactional context. Insight into the motivations behind any language choice can only be gained through close knowledge of the community and the social identities and interactional goals of the interlocutors involved. As an outsider to the community, it is important to be circumspect about assigning meaning and intent to the ways in which speakers draw upon their own resources (Wei 1998). I have been assisted greatly in these analyses by conversations with the relevant speakers and extended time spent in Maningrida but, nevertheless, any analysis of these complex factors must inevitably be incomplete and reductive.

5. Conclusions: Linguistic and Social ‘Congruence’ in Local Outcomes of Language Contact

Exploring of the shape and function of code-switching and language choice in a particular community provides a rich insight into local ontologies of language, culture and personal identity. In this case, this exploration has also revealed further evidence of the rich, creative and adaptive language practices of Indigenous speakers amidst rapidly shifting ‘langscapes’ (Angelo 2006). In this paper, I have delineated aspects of the place of code-switching in a contemporary, highly diverse Indigenous language ecology in northern Australia by contributing recent data from a range of multilingual community interactions. These data have been interrogated to provide insights into how code-switching may have changed in form and function since colonisation, and to better understand the observable differences between switching between traditional languages on the one hand, and switching between a traditional language and English or Kriol on the other. The data have further served as a limited testing ground for general predictions from dominant theories of code-switching in the field. These explorations have revealed that although many of the linguistic factors favoured in the literature as key drivers of the shape of code-switching (e.g., the matrix language frame model, typological congruence) are observable in operation in Maningrida, the extent of their influence is somewhat attenuated, and their operation interacts fundamentally with social and ideological pressures. Shifting socio-interactional goals and especially constraints exerted by local ideologies of multilingualism and linguistic purism have a significant effect, not just on the motivations behind code-switching but also on the particular linguistic characteristics of the practice. Specifically, intrasentential (both insertional and alternational) code-switching between local traditional languages has been shown to be substantially restricted despite predictions that greater typological congruence between the lects ought to facilitate the practice among bi/multilinguals. In this sense, I suggest that codes may be linguistically ‘congruent’ but not socially congruent (Sebba 1998), and that both linguistic/typological and social-psychological pressures fundamentally contribute to shaping the diverse outcomes of language contact.

Ultimately, this investigation of code-switching and language choice has also been an exploration of local understandings of cultural and linguistic boundary maintenance, and of the maintenance and even cultivation of difference. Linguistic difference, in the Maningrida region, is not a source of division but rather is “part of the common condition […] internal to society, not markers of the edges of different societies” (Sutton 1997, p. 240). These ideologies also have reflexes in language-internal variation (such as in the ‘deliberate elaboration’ of dialectal differences (Garde 2008)) and in other cultural domains such as art, music, ceremony and football (e.g., Keen 1994; Elliott 1991; Brown 2016). These formations, and the particularities of code-switching in Maningrida, are also comparable to other regions in the world characterised by small-scale, egalitarian multilingualism—for example, the avoidance of code-switching between local languages (but not between these and European-mediated contact languages) in the highly multilingual Vaupés region of the Amazon basin (e.g., Epps 2018) and the strong sociolinguistic loyalties to the patrilect among women in the Sui villages of southwestern China (Stanford 2009). In these regions, as in Arnhem Land, local ideologies of divergence and convergence in cultural and linguistic practice have helped explain local particularities in language contact outcomes.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Endangered Languages Documentation Project (C.I. Jill Vaughan, grant IPF0256), the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (C.I. Felicity Meakins, University of Queensland, grant CE140100041), the Linguistic Complexity in the Individual and Society project (C.I. Terje Lohndal) at the Norwegian University for Science and Technology, and a University of Melbourne Early Career Researcher Grant (C.I. Jill Vaughan).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Humanities Law & Social Sciences Human Ethics Sub-Committee of the University of Melbourne (ID 1851389.1, approved 4th May 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results is accessible through the Endangered Languages Archive at https://elar.soas.ac.uk/Collection/MPI1079933 (accessed on 17 May 2021).

Acknowledgments

This research is deeply indebted to the contributions of many members of Maningrida community, to Indigenous knowledge holders of all the languages and cultures mentioned here, and to their generosity and trust in sharing their knowledge with me. I am especially grateful to Abigail Carter, Doreen Jinggarrabarra, Stanley Rankin, Cindy Jin-marabynana, Laurie Guraylayla, Betty Nguraba Nguraba, Rebecca Baker and Joseph Diddo.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| : | Subject acting on object |

| 1 | First person exclusive |

| 12 | First person inclusive |

| 2 | Second person |

| 3 | Third person |

| a | Augmented number |

| att | Attention getter |

| c | Contemporary tense |

| dat | Dative |

| dem | Demonstrative |

| der | Denominaliser/deverbaliser |

| dist | Distal demonstrative |

| dur | Durative |

| emph | Emphasis |

| exc | First or second person exclusive |

| f | Feminine |

| foc | Focus demonstrative |

| fut | Future |

| i, ii, iii, iv | Noun class: male, female, edible and land |

| im | Imperfective aspect |

| loc | Local case |

| m | Masculine |

| npst | Non-past |

| opp | Opposite demonstrative |

| pc | Precontemporary tense |

| pl | Plural number |

| prox | Proximal demonstrative |

| rls | Realis |

| sg | Singular |

| tf | Temporal focus |

| to | Directional prefix |

| ua | Unit augmented number |

References

- Angelo, Denise. 2006. Shifting Langscape of Northern Queensland. Paper presented at the Workshop on Australian Aboriginal Languages, Sydney, Australia, March 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, Peter. 1998. Code-Switching in Conversation: Language, Interaction and Identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, Peter. 1999. From codeswitching via language mixing to fused lects: Toward a dynamic typology of bilingual speech. International Journal of Bilingualism 3: 309–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, Ad. 2003. Can a mixed language be conventionalized alternational codeswitching? In The Mixed Language Debate: Theoretical and Empirical Advances. Edited by Yaron Matras and Peter Bakker. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 237–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, Ephraim. 1976. The language situation in the Torres Strait. In Languages of Cape York. Edited by Peter Sutton. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Allan. 2001. Back in style: Reworking audience design. In Style and Sociolinguistic Variation. Edited by Penelope Eckert and John R. Rickford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139–69. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Paul. 1997. Lexicostatistics and Australian languages: Problems and prospects. In Boundary Rider: Essays in Honour of Geoffrey O’Grady. Edited by Darrell Tryon and Michael Walsh. Pacific Linguistics C-136. Canberra: Australian National University, pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, Jan-Petter, and John J. Gumperz. 1972. Some social determinants of verbal behaviour. In Directions in Sociolinguistics. Edited by John Gumperz and Del Hymes. New York: Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Bowern, Claire, and Quentin Atkinson. 2012. Computational phylogenetics and the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan. Language 88: 817–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, John. 1988. Yanyuwa: “Men speak one way, women speak another. ” Aboriginal Linguistics 1: 126–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Reuben. 2016. Following Footsteps: The Kun-Borrk/Manyardi Song Tradition and Its Role in Western Arnhem Land Society. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Carew, Margaret. 2016. Gun-ngaypa Rrawa “My Country”: Intercultural Alliances in Language Research. Ph.D. Thesis, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Carew, Margaret. 2017. Gun-nartpa Grammar. Available online: http://call.batchelor.edu.au/gun-nartpa-grammar/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Carew, Margaret. forthcoming. The Maningridan languages, with a focus on Burarra and Gun-nartpa. In Oxford Handbook of Australian Languages. Edited by Claire Bowern. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chan, Brian Hok-Shing. 2009. Code-switching between typologically distinct languages. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-Switching. Edited by Barbara E. Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 182–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Michael. 1967. Transference and Triggering: Observations on the Language Assimilation of Postwar German-Speaking Migrants in Australia. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, Michael. 1980. Triggering and language processing. Canadian Journal of Psychology 34: 400–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Michael. 1987. Constraints on codeswitching: How universal are they? Linguistics 25: 739–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Michael. 2003. Dynamics of Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Ron. 1983. The language situation on Mer. In Ngali: School of Australian Linguistics Newsletter: 1983. Batchelor: School of Australian Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Robert M. W. 1970. Languages of the Cairns rain forest region. In Pacific Linguistic Studies in Honour of Arthur Capell. Pacific Linguistics C-13. Edited by Stephen A. Wurm and Donald C. Laycock. Canberra: Australian National University, pp. 651–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Robert M. W. 1980. The Languages of Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 2007. Putting communities of practice in their place. Gender and Language 1: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Craig. 1991. “Mewal is Merri’s Name”: Form and Ambiguity in Marrangu Cosmology, North Central Arnhem Land. Master’s Arts Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Elwell, Vanessa. 1977. Multilingualism and Lingua Francas among Australian Aborigines: A Case Study of Maningrida. Honours Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Elwell, Vanessa. 1982. Some social factors affecting multilingualism among Aboriginal Australians: A case study of Maningrida. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 36: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfield, Nick. 2009. The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture and Composite Utterances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epps, Patience. 2018. Contrasting linguistic ecologies: Indigenous and colonially mediated language contact in northwest Amazonia. Language & Communication 62: 156–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Nicholas. 2010. A tale of many tongues: Polyglot narrative in North Australian oral traditions. In Indigenous Language and Social Identity: Papers in Honour of Michael Walsh. Edited by Brett Baker, Ilana Mushin, Mark Harvey and Rod Gardner. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, pp. 275–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Joshua. 1967. Bilingualism with and without diglossia: Diglossia with and without bilingualism. Journal of Social Issues 23: 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, Joshua. 1972. Domains and the relationship between micro- and macro- sociolinguistics. In Directions in Sociolinguistics. Edited by John Gumperz and Del Hymes. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 435–53. [Google Scholar]

- François, Alexandre. 2012. The dynamics of linguistic diversity: Egalitarian multilingualism and power imbalance among northern Vanuatu languages. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 214: 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]