Abstract

There is a longstanding debate in the literature about if, and where, recursion occurs in prosodic structure. While there are clear cases of genuine recursion at the phrase level and above, there are very few convincing cases of word-level recursion. Most cases are—by definition—not recursive and instead best analyzed as different constituents (e.g., the Composite Group, Prosodic Word Group, etc.). We show that two convincing cases of prosodic word-level recursion can easily be reanalyzed without recursion if phonology and prosody are evaluated cyclically at syntactic phase boundaries. Our analysis combines phase-based spell-out and morpheme-specific subcategorization frames of Cophonologies by Phase with Tri-P Mapping prosodic structure building. We show that apparent word-level recursion is due to cyclic spell-out, and non-isomorphisms between syntactic and prosodic structure are due to morpheme-specific prosodic requirements.

1. Introduction

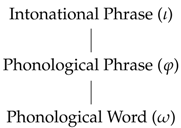

Phonology is sensitive to prosodic structure related to—but not necessarily identical to—morpho-syntactic structure. The following interface constituents (above the word level) are widely accepted as members of the Prosodic Hierarchy (originally formalized in Nespor and Vogel 1986; Selkirk 1986).

- (1)

There is a longstanding debate in the literature about if, and where, recursion occurs in prosodic structure (e.g., Cheng and Downing 2021; Itô and Mester 2009a; Selkirk 1995, 2011; Truckenbrodt 1999; Vogel 2009a, 2019; Wagner 2005). While there are clear cases of genuine recursion of constituents at and above (Selkirk 2011), there are very few convincing cases of word-level recursion. Most cases are—by definition—not recursive and instead best reanalyzed as different constituents (e.g., the Composite Group in Vogel 2019, the Prosodic Word Group in Vigário 2010, Constituent in Miller 2020, the Prosodic Stem in Downing 1998, 1999). In fact, to date, we have only found two convincing cases for word-level recursion: Bennett (2018)’s analysis of Kaqchikel inner and outer affixes and Weber (2020)’s analysis of embedded roots in Blackfoot.

This paper investigates the question of whether there are any true cases of recursion at the word level. We show that the few possible candidates for genuine word-level recursion can easily be reanalyzed without recursion if phonology and prosody are evaluated cyclically at syntactic phase boundaries. Our analysis combines phase-based spell-out and morpheme-specific subcategorization frames of Cophonologies by Phase (CbP) (Sande 2017, 2019; Sande et al. 2020) with Phase-based Prosodic Phonology (Tri-P Mapping) prosodic structure building (Miller 2018, 2020). By doing so, we expand on the CbP literature, fleshing out how CbP can build prosodic structure by combining it with Tri-P. Apparent word-level recursion can be reanalyzed as due to cyclic spell-out, and non-isomorphisms between syntactic and prosodic structure are due to morpheme-specific prosodic requirements. As a consequence, no attested cases of word-level recursion actually require a recursive analysis, and we can maintain that phonology below the phrase does not involve recursive structures.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: in Section 2, we provide an overview of the three categories of existing recursive word proposals: compound phonology (Section 2.1), different prosodic domains with distinct phonological properties (Section 2.2), and iterative application of the same phenomena (Section 2.3). We provide a definition of recursion, which rules out the first two categories and selects the third as the focus of this paper. In Section 3, we introduce Tri-P Mapping and Cophonologies by Phase to be used in the subsequent analyses. Section 4 and Section 5 are dedicated to two possible genuine cases of word-level recursion. Each section provides an overview of the relevant data, the previous analyses, and our revised analysis that does not involve recursive structures. Finally, Section 6 includes a discussion of the wider implications of our results, questions for future research, and our conclusions.

2. Recursion at the Word-Level

We propose that current recursive word proposals fall into three categories: compound phonology, different prosodic domains with distinct phonological properties, and iterative application of the same phenomena. The vast majority of work is found in the first two categories, which we posit are not actually instances of recursion. Aligning with recent work by Downing and Kadenge (2020) based on definitions provided in Jackendoff and Pinker (2005) and Vogel (2012), we define prosodic recursion as follows:

- (2)

- Prosodic structure exhibits recursion if the constituents in question:

- a.

- are mapped in the same way from morphosyntactic structure, and

- b.

- are hierarchically embedded (an entity of prosodic category X is an atom hierarchically within another entity of prosodic category X), and

- c.

- share identical phonological properties (i.e., the same phonological processes apply iteratively at each recursive level)

2.1. Compound Phonology as “Recursion”

First, recursive word proposals have been put forth for compounds in numerous languages (among others, Danish in Itô and Mester 2015; Kalivoda and Bellik 2018; Dutch in Wheeldon and Lahiri 2002, Finnish in Karvonen 2005, Italian in Peperkamp 1997, Japanese in Itô and Mester 2007, Korean in Han 1994, Murrinhpatha in Mansfield 2017, Portuguese in Vigário 2003, Russian in Gouskova 2010, Somali in Green and Morrison 2016, Spanish in Shwayder 2015, and Swedish in Myrberg and Riad 2015). In each case, however, the recursive word containing the full compound demonstrates different phonological properties than that of the inner word (i.e., compound-specific phonology). Thus, none of these cases demonstrate genuine recursion according to (2).

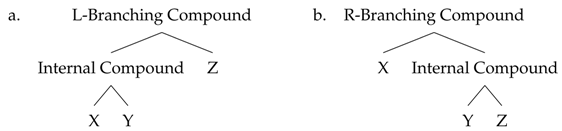

As an example, consider Itô and Mester’s analysis of Japanese branching compounds. Each compound consists of three elements X, Y, and Z, and two of the elements join together to form an internal compound within the larger compound. The compound may be left-branching with component members [XY] and [Z] (3a) or right-branching with component members [X] and [YZ] as in (3b).

- (3)

In a left-branching compound, the second member [Z]—or head—is assigned a junctural accent (a HL tone). Any lexical accent present when that member is an independent word is replaced. If the first member bore a lexical accent, it is then deaccented. Finally, rendaku—or compound voicing—applies across the two members. Consider the compound for ‘climbing of badger valley’, which shows /t/ surfacing as [d] in ‘valley.’

- (4)

- Left-Branching Compound

/tanúki/ + /taní/ + /nobori/ → [[tanukidani]nóbori] badger + valley + climbing → climbing of badger valley

Rendaku never applies in right-branching compounds. Instead, three types of right-branching compounds differ entirely according to whether or not they exhibit junctural accent and/or deaccentuation. The first type (henceforth R-1) exhibits both the junctural accent and deaccentuation:1

- (5)

- R-1 Type Compound2

/genkín/ + /furí/ + /komi/ → [genkin[fúrikomi]] cash + transfer + transfer → cash transfer

The second type (R-2) exhibits deaccentuation but not the junctural accent.

- (6)

- R-2 Type Compound

/hatsú/ + /kao/ + /áwase/ → [hatsu[kaoáwase]] first + face + meeting → first face-to-face meeting

The third type (R-3) exhibits neither the junctural accent nor deaccentuation.

- (7)

- R-3 Type Compound

/zénkoku/ + /kaisha/ + /annái/ → [zénkoku[kaishaánnai]] nationwide + corporate + guide → nationwide corporate guide

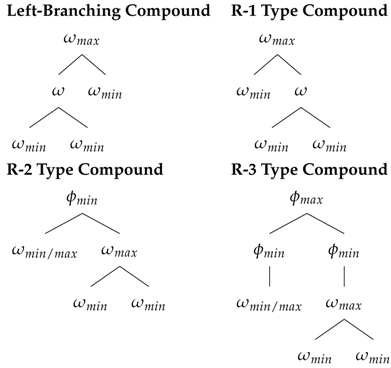

Itô and Mester rely on recursive words and phrases to account for the phenomena in (5)–(7) above. Left-Branching compounds are mapped using Align-L (, MWd) requiring s and morphological words to align at the left edge. R-1 and R-2 Type Compounds arise from a combination of Align-Left (, MWd) and two other constraints: MaxBin (Head()) requiring the head of a compound to be maximally binary and Wrap (, MWd) requiring a morphological word consist of one . Since MaxBin (Head()) is ranked above Wrap (, MWd), it ensures that “super-binary” heads in R-2 Type Compounds map as joining with the other compound element at the phrase-level as in (8). R-1 Type compounds do not violate MaxBin (Head() and therefore may surface as all s (like the seen in (8b) below). Though these would include three word-levels, only minimal and maximal levels are referenced in the analysis.

- (8)

- Align-Left (, MWd) >> MaxBin (Head()) >> Wrap (, Mwd)

/{{hatsu{{kao}{áwase}}} / Align-L (, MWd) MaxBin (Head()) Wrap (, Mwd) a. ☞[(hatsu) ((kao) (áwase))] * b. ((hastu) ((k’ao) (awase))) *!

Itô and Mester explain that R-3 Type Compounds (those with two phrase-levels) may arise due to multiple factors. In some cases, the compound head exceeds three feet suggesting a threshold which triggers phrase-parsing (e.g., MaxTri). The first member in some cases is intrinsically marked as phrasal (e.g., móto ’former’) suggesting the head may parse as phrasal in parallelism. The exact reason for bi-phrasal compounds was left to future research. Interested readers are directed to Itô and Mester (2007) and the sources cited therein for more discussion.

The prosodic structures for each type of compound (min/max levels indicated as such with subscripts) are provided below.

- (9)

- Prosodic Structure of Compounds (Itô and Mester 2007, p. 7)

First, rendaku is limited to the minimal word. Specifically, it may apply in minimal words where the first is not the first member of a maximal word. In other words, left-branching compounds exhibit two potential rendaku sites in (9): the second and third . In all right-branching compounds, the only potential site for rendaku is the final inside the internal compound.

Second, the junctural accent is assigned at the maximal word. Specifically, it applies at the juncture between its minimal word members. This explains why we only see the junctural accent apply in left-branching and R-1 Type Compounds, as they are headed by maximal word projections. R-1 and R-2 Type Compounds are headed by types of phrases and are thus exempt.

Finally, deaccentuation falls out from pitch accent acting as a head feature in Japanese. Specifically, each accent must be the head of a minimal phrase. As Japanese compounds are right-headed, the only heads of minimal phrases which are allowed to retain their accents are the second in an R-2 Type Compound and both s in an R-3 Type Compound. All other maximal words will deaccentuate.

While it is clear that there are multiple interacting phonological domains in Japanese compounds, the maximal and minimal projections proposed by Itô and Mester cannot be instances of the same prosodic constituent according to the definition in (2). Aside from the fact that these levels demonstrate different properties in compounds, a larger look at Japanese further cements that they are not in fact the same. Itô and Mester mention further phonological corroboration for the minor word in Japanese—velar nasalation and epenthesis as discussed in Itô and Mester (2003)—but these are not present at higher levels. Thus, we argue such a proposal does not in fact show recursion at the word-level but merits future reanalysis.

2.2. Distinct Domains and Properties as “Recursion”

Recursive words are often proposed to account for the phonology of function words, clitics, and noncohering affixes. While some researchers don’t distinguish levels of recursion, many choose to distinguish the different domains like the compound analyses above by assigning them different names such as “Major Word” for the outer phonological word and “Minor Word” for the inner phonological word. Though given different names and showing a different set of properties, they are often still considered recursive instances of the same prosodic constituent (Booij 1996; Booij and Rubach 1984, 1987; Guekguezian 2017a, 2017b; Hall 1999; Hildebrandt 2007, 2015; Itô and Mester 2003, 2007, 2009a, 2009b, 2012, 2013, 2015; Kabak and Revithiadou 2009; Nikolou 2008; Peperkamp 1997; Selkirk 1996, 2011; van der Hulst 2010, among many others).3 In the majority of the above cases, there are at most two proposed prosodic levels (an inner and outer word), though some authors argue for more (e.g., three words in Hildebrandt 2007) or that there could be unlimited word domains depending on the language (e.g., Schiering et al. 2010). Regardless, the different levels are again characterized by different phonological properties. Thus, as with the compound analyses above, they do not satisfy the definition in (2).

As an example, consider Limbu, which, as Schiering et al. point out, shows multiple distinct word-internal levels, which cannot be analyzed as recursive due to their differing phonological processes. In Limbu, nouns and verbs are organized according to morpheme templates or slots of the form prefix–stem–suffix=clitic where multiple prefixes, suffixes, and clitics are possible. Two word-level domains are identified: the major prosodic word (prefix–stem–suffix=clitic) and the minor prosodic word (stem–suffix=clitic). The major prosodic word is the domain for stress assignment and coronal-to-labial assimilation. Primary stress is realized on stem-initial syllables, which means that stress may be found initially in words that do not include a prefix (10) or on the second syllable in prefixed words (11). If stem-initial stress would form an illicit iambic foot (Limbu requires bimoraic trochaic feet), stress shifts to the prefix as in (12). Thus, the prefix is included in the stress domain, too, or in a second iteration of stress assignment that differs from initial stress assignment at the minor word level:

- (10)

/pe:g -i/ [ˈpe:gi] stem -suffix go -IPL.S ‘We go’

- (11)

- a.

/a- oŋ -e:/ [ʔaˈʔoŋˌŋe:] prefix- stem -suffix 1POSS- brother.in.law -VOC ‘My brother in law!’ - b.

/ku- taŋ =mε/ [kuˈtaŋmε] prefix- stem =clitic 3POSS- horn =CTR ‘its horn, on the contrary’ - c.

/mε- tanŋ -e =aŋ/ [mεˈthaŋˌjaŋ] prefix- stem -suffix =clitic 3NS- come.up -PST =and ‘they come up and...’

- (12)

/ku- laːp/ [ˈkulaːp] prefix- stem 3POSS- wing ‘its wing’

The major prosodic word is also the domain for regressive coronal-to-labial assimilation (13). Coronals (/t/ and /n/) become bilabial before bilabials (/p/ and /m/) across the entire template within the major prosodic word (14).4

- (13)

- Regressive Coronal to Labial Assimilation

- (14)

- a.

/ɔ:mɔt -maʔ/ [ʔɔ:mɔpmaʔ] stem -suffix look.at -INF ‘I did not tell him’ - b.

/mε- n- mε -paŋ/ [mεmmεppaŋ] prefix- prefix- stem -suffix NS.A- NEG- tell -1SG>3PST ‘I did not tell him.’ - c.

/si -aŋ -mεn -pa/ [sjaŋmεmba] stem -suffix -suffix -suffix die -1SG.S.PST -COND -IPFV ‘I might die’ - d.

/myaŋluŋ =hεlle hεn =phεlle/ [mjaŋluŋbhεllε hεmbhεlle] stem =clitic stem =clitic Myaŋluŋ =SUB what =SUB ‘What does Myaŋluŋ mean?’

The minor prosodic word is the domain for an [l]∼[r] alternation and [ʔ]-Insertion process. In Limbu, /l/ surfaces as [r] word-medially after open syllables or syllables ending in /ʔ/. It surfaces as [l] elsewhere.5 As seen in (15), this alternation is present in morphologically simple and complex words. It is also present in words with complex stems and clitics (16). In both (15) and (16), the forms on the left show /l/ following an open syllable and thus undergoing the change to [r], and the forms on the right show /l/ following a closed syllable and thus surfacing unchanged.

- (15)

a. neret b. lipli ‘heart’ ‘earthquake’ c. pha -re siŋ d. mik -le raŋ stem -suffix stem stem -suffix stem bamboo -GEN wood eye -GEN color ‘the wood of bamboo’ ‘the color of the eyes’

- (16)

a. peːg -i =roː b. peːg -aŋ =loː stem -suffix =CLITIC stem -suffix =CLITIC go -PL =ASS go -1SG.PST =ASS ‘come on, let’s go!’ ‘I’m on my way!’

Crucially, however, /l/ surfaces unchanged across the prefix-stem boundary, thus excluding prefixes from the minor prosodic word (17a).

- (17)

- a.

ke- lɔʔ prefix- stem 2- say ‘you say’ - b.

mε l- lε -baŋ prefix- prefix- stem -suffix NEG- NEG- know -1SG>3.PST ‘I didn’t know it’

The minor prosodic word also forms the domain for [ʔ]-insertion, which epenthesizes a [ʔ] before a vowel-initial stem as in (18a). The process also applies when the stem follows a prefix (18c), indicating that the domain is not simply word-initial insertion. Crucially, the process still applies even after a vowel-final prefix in (18c). In contrast, vowel hiatus after the stem is resolved through diphthongization as in (18d). Thus, the prefix is not included in the same phonological domain as the stem. Otherwise, dipthongization would apply.

- (18)

- a.

/iŋghɔŋ/ [ʔiŋghɔŋ] ‘message’ - b.

/ku- iŋghɔŋ/ [kuʔiŋghɔŋ] prefix- stem 3POSS- message ‘his news’ - c.

/a- iːr -ε/ [ʔaʔiːrε] prefix- stem -suffix I- wander -PST ‘We (plural, inclusive) wandered.’ - d.

/nu- ba =iː/ [nubaiː] stem -suffix =clitic be.alright -NOM =Q ‘Is it good?’

Schiering et al. have clearly identified two distinct phonological domains for Limbu, one forming the domain for stress and coronal labial assimilation and one forming the domain for the [l]∼[r] alternation and [ʔ]-insertion.6 As Schiering et al. point out, they cannot be instances of the same prosodic constituent according to our definition in (2). The two domains demonstrate entirely different phonological properties. Thus, Limbu word-internal domains do not show recursion at the word-level but require reference to multiple (sub-)word prosodic levels.

2.3. Iterative Application as Convincing Recursion

Once we rule out recursive proposals pertaining to compound phonology and distinct domains and properties, we are left with instances of convincing recursion. In accordance with (2), multiple word levels exhibit iterative application of the same phonological processes and properties. To date, we have only identified two such proposals: Bennett’s 2018 analysis of Kaqchikel inner and outer affixes and Weber’s 2020 analysis of Blackfoot embedded roots. Both analyses are presented in detail in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively.

While we acknowledge that other convincing cases may exist or may be proposed in the future, the fact that we find only two in the vast recursive word literature is telling. Word-level recursion, if it exists, is rare. Thus, we argue that, if reanalysis is possible, it is preferred. Restricting recursion to the phrase and above confirms that there is a fundamental difference between phonology and syntax, and it is reflected in the Prosodic Hierarchy (see also Vogel 2019). Though as we discuss in Section 6, the precise way in which recursion is banned and what that means for the prosodic hierarchy as a whole is an issue for future research.

3. The Models

3.1. Tri-P Mapping

Tri-P Mapping (or Phase-based Prosodic Phonology)7 is a model of the phonology–syntax interface, which builds on Miller’s (2018) findings that current interface models (i.e., Relational Mapping as in Nespor and Vogel 1986; Vogel 2019; Syntax-Driven Mapping as in Selkirk 2011; and Syntactic Spell-Out Approaches as in Pak 2008; Sato 2006; Samuels 2011) fall short when tested against data from languages with extreme morpho-syntactic complexity. Relational Mapping and (Direct Reference) Syntactic-Spell Out Approaches alone correctly predicted verb-internal domains in languages like Kiowa and Saulteaux Ojibwe, but neither provided full accounts for either language. Arguing a combined approach with assumptions from both models is necessary, and (Miller 2018, 2020) advanced such a model in Tri-P Mapping.

Tri-P Mapping uses an Indirect Reference strategy for mapping prosodic constituents from morpheme- and clause-level phases (Miller 2018, 2020). Phonology may reference any spelled-out phase to map to prosodic structure, but phonology itself does not apply cyclically.8 This allows for domains of smaller sizes, as opposed to work like Cheng and Downing (2016) which assumes phonology applies after all Spell-Out operations.

As in other Indirect Reference Spell-Out accounts (Ahn 2015; Cheng and Downing 2007; Compton and Pittman 2007; Dobashi 2003, 2004a, 2004b; Ishihara 2007; Kratzer and Selkirk 2007; Piggott and Newell 2006), morpheme-level phases (those headed by a categorizing head) map to and clause-level phases little v/voice map to . C’s phase maps to . Phonologically motivated restructuring may then occur including or excluding various elements within the tree. In the discussion below, a revised definition for becomes necessary. See Section 5.3 for that discussion.

Crucially, recursion is banned below , as in Vogel’s Composite Prosodic Model (Vogel 2019). This suggests at least one intermediate constituent between and is necessary: Constituent . We leave discussion of this ban and its implications for compounds, morphologically conditioned phenomena, and outer prosodic domains to Section 6.

3.2. Cophonologies by Phase

Cophonologies by Phase (CbP) is a model of the interface between morphosyntax and phonology, which assumes late insertion of vocabulary items, spell-out at syntactic phase boundaries, and a constraint-based phonology (Sande 2019, 2020; Sande and Jenks 2018; Sande et al. 2020). The innovation of CbP is in the content of vocabulary items, or lexical items. Specifically, in addition to their phonological feature content (), vocabulary items also contain a prosodic subcategorization frame (Inkelas 1990; Paster 2006), and a morpheme-specific constraint ranking adjustment (19).9

- (19)

- Example CbP vocabulary entry[n]

The segmental and suprasegmental content of the plural marker in (19) is /in-/, the prosodic subcategorization frame says it should be a prefix within a prosodic word, and the constraint adjustment tells the phonological grammar to rank NasalPlaceAssimilation above Ident-Place. In the spell-out domain containing the morpheme in (19), the default ranking of Ident-Place ≫ NasalPlaceAssimilation will be reversed, resulting in assimilation in this domain, even if assimilation is not a general process in the language. That is, similar to traditional Co-Phonology Theory (Anttila 2002; Inkelas and Zoll 2005; Orgun 1996), there are multiple phonological rankings of constraints within the same language, which vary with the specific morphemes present in a spell-out domain. The key difference is that, in CbP, phonological evaluation applies at phase boundaries, rather than on the addition of each morpheme.

The result of adding morpheme-specific constraint ranking adjustments to vocabulary items is a specific mechanism of communication between the morphology and phonology, such that the phonology knows which grammar or cophonology to apply in a given instance of phonological evaluation. Additionally, the fact that CbP assumes spell-out at syntactic phase boundaries means that morpheme-specific effects are predicted to apply within the phase in which they are introduced, but they are not predicted to affect morphemes introduced in higher phase boundaries (20).

- (20)

- Phase containment principle (Sande and Jenks 2018; Sande et al. 2020):Morphophonological operations conditioned internal to a phase cannot affect the phonology of phases that are not yet spelled out.

The phase containment principle, which is related to previous predictions of level-ordering theories and cophonologies (cf. Orgun and Inkelas 2002) holds of morpheme-specific constraint rankings, but also of morpheme-specific prosodic subcategorization effects, as will be shown in Section 4 and Section 5.

Previous work in CbP has shown that this framework can account for morpheme-specific phonological effects that apply in domains smaller than a word (Sande 2019), larger than a word (Sande and Jenks 2018; Sande et al. 2020), competing morpheme-specific specifications within a phase (Sande et al. 2020), category-specific effects (Sande and Jenks 2018; Sande et al. 2020), and morpheme-specific phonology conditioned by two simultaneous morphological triggers within a phase domain (Sande 2020). Here, we show that phase based spell-out can account for effects that have previously been claimed to involve recursive prosodic word boundaries. While the predictions of the morpheme-specific constraint ranking associated with CbP vocabulary items have been thoroughly examined (Sande 2019, 2020; Sande et al. 2020), this paper begins to explore the predictions of the morpheme-specific prosodic subcategorization frame in CbP.

3.3. Combining Tri-P Mapping and Cophonologies by Phase

Both CbP and Tri-P mapping assume phase-based spell-out. We combine CbP vocabulary items with the syntax-to-prosody mapping of Tri-P, resulting in a model that predictably builds prosodic structure at syntactic boundaries and applies morpheme-specific effects within those boundaries. We show that, in this model, two of the most convincing cases of recursive prosodic words—Kaqchikel glottal stop insertion (Section 4) and Blackfoot embedded roots (Section 5)—need not actually be analyzed as involving word-level recursion.

4. Kaqchikel Inner and Outer Affixes

4.1. Kaqchikel Data

In Kaqchikel (Mayan, Guatemala), Bennett (2018) argues that there is evidence of prosodic word-level recursion: [[]]. He proposes two sets of prefixes, high-attaching and low-attaching, which show different sets of phonological properties. Generally across the language, underlying vowel-initial words surface with an initial glottal stop. All examples provided here come from (Patal Majzul 2007) and are cited by (Bennett 2018).

- (21)

- Initial glottal stop insertion

- a.

- ik [ʔikh] ‘chile’

- b.

- ixim [ʔi.ˈʃim] ‘corn’

- c.

- eleq’om [ʔe.le.om] ‘thief’

Vowel-initial roots do not surface with an initial glottal stop after low-attaching prefixes. Low-attaching prefixes include aspect marking (22a), ergative possessives (22b), and agreement on verbs (22c).

- (22)

- Low-attaching prefixes block glottal stop insertion

- a.

∫-ok 3sg-enter ‘(s)he entered’ (*∫-ʔok) - b.

r-ut∫uaʔ 3sg.poss-strength ‘his/her strength’ (*r-ʔut∫uaʔ) - c.

∫-aw-i 3sg-2sg-find ‘you found it’ (*∫-aw-i)

However, when high-attaching prefixes are present, we see glottal stop insertion before the root-initial vowel, immediately following the high prefix (as well as at the beginning of the whole word, if the prefix is vowel-initial). High attaching prefixes include absolutive prefixes on non-verbal predicates (23a) and derivational morphology like agentive nominalizers (23b). Bennett (2018) differentiates high-attaching prefixes from low-attaching ones in by using ‘=’ rather than ‘-’ to demarcate them. We follow his notation here in examples, but not in formal representations like tableaux. When multiple vowel-initial high-attaching prefixes are present on the same root, we see multiple instances of glottal stop insertion (23c):

- (23)

- High-attaching prefixes and glottal stop insertion

- a.

oj aq ʔoχ=ʔaqx 1pl=pigs ‘We are pigs’ (cf. r-aqx ‘his/her pig) - b.

ajejqa’n ʔaχ=ʔeχqaχn agt=cargo ‘porter’ (cf. r-eχqaʔn ‘his/ her cargo’) - c.

in ajik’ ʔin=ʔaχ=ʔikʔ 1sg.abs=agt=month ‘I am a domestic worker’

Other phonological processes are also sensitive to the low—versus high—attaching boundary. Degemination of adjacent identical consonants across a morpheme boundary applies between low-attaching prefixes and roots, but not between high-attaching prefixes and roots Bennett (2018, p. 7).

4.2. Previous Analysis: Recursive Words

Bennett adopts a recursive word analysis of the Kaqchikel data, where word-initial vowels are preceded by a glottal stop, and high-attaching prefixes introduce additional word boundaries while low-attaching prefixes do not: [LowPref-Stem], [HighPref=[ Stem]]. He uses a Match constraint (Selkirk 2009, 2011) to ensure that morphological words (terminal nodes) are dominated by a single prosodic word, and adopts an OCP constraint active within but not across word boundaries to account for gemination. He shows that an alternative prosodic parse involving a lack of recursion and a constituent intermediate between prosodic word and phonological phrase is not sufficient to account for the Kaqchikel facts, since, when multiple high-attaching prefixes are present, we would need to posit multiple intermediate phrase types to avoid recursion, and all of them would coincidentally undergo the same processes as word boundaries (see example 23c).

Bennett considers numerous analytical options for differentiating low-attaching from high-attaching prefixes in the grammar. He ultimately determines that a subcategorization account makes the best predictions for the data. High-attaching prefixes are associated with a lexically listed subcategorization frame specifying that they attach to a prosodic word and are dominated by a prosodic word: [ HighPrefix [ ]].

He rules out a stratal or level-ordering account because it would predict that all low-attaching affixes surface closer to the root than high-attaching prefixes, which is not the case. Low-attaching prefixes (ergative possessive) can appear outside of high-attaching prefixes (agentive) (24):

- (24)

- Order of low- and high-attaching prefixes

- a.

r-aχ=toʔ-o 3sg.erg-agt=help-nmlz ‘his/her helper’ - b.

w-aχ=tʔis 1sg.erg-agt=sew ‘my tailor’

He also rules out a morphosyntactic account of differentiating high- from low-attaching prefixes. His explanation is that, if categorizing prefixes like the agentive are high-attaching, we would expect all categorizing affixes to pattern the same way. While some derivational affixes like the agentive are high-attaching, there is a nominalization suffix /-il/ which is never preceded by a glottal stop. This argument does not suffice, however, since definitionally we would never expect the /-il/ suffix to be word initial under any prosodic parse; it is a suffix. If there was a word boundary between the stem and suffixal high prefix, we would expect the structure [ [ Stem]-il]. If it does not introduce a prosodic boundary, we’d expect the prosodic parse [ Stem-il]. Either way, the suffix is not at the beginning of a prosodic word, so it is not predicted to be preceded by a glottal stop. Appropriate counterevidence to a morphosyntactic account would be a derivational (categorizing head) vowel-initial prefix that patterns phonologically differently from, say, the Kaqchikel agentive prefix. We do not see such a prefix in the data.

4.3. Updated (Non-Recursive) Analysis: Phase-Based Spell-Out

Here, we enhance Bennett’s account of high and low prefixes, showing that a morphosyntactic account indeed can differentiate high from low prefixes, and does so in a principled rather than coincidental way. Specifically, high-attaching prefixes are proposed to be syntactic phase heads. Phase heads trigger spell-out of their complements, and phonology applies at phase boundaries (Miller 2020; Sande 2019; Sande et al. 2020). Following Miller (2020), phases headed by C map to , other clause-level phases such as v/Voice map to , and “morpheme-level” phases map to , or prosodic words. We propose that all high-attaching prefixes such as the agentive introduce morpheme-level phase boundaries, triggering spell-out of their complements, which map to prosodic words.

At each instance of spell-out, if a word (the spell-out domain) is vowel-initial, a glottal stop is inserted before the vowel due to regular phonological constraint interaction: Onset ≫ Dep. At later phase domains when more material is added, the glottal stop may no longer be word-initial, but its presence reflects that it was initial during one instance of cyclic spell-out.

A notable fact about the data is that glottal-stop insertion takes place after high-attaching prefixes, not before them unless they are vowel-initial and there is no additional affix to their left. Thus, the high-attaching prefixes themselves are not the left edge of a spell-out domain, but their complement is. Existing ideas about phase boundaries assume that a phase head triggers spell-out of its complement (Abels 2012; Bošković 2014; Chomsky 2001, 2004, 2008), which is consistent with what we see in the data. However, this idea differs from previous assumptions in Tri-P mapping (Miller 2020) and Cophonologies by Phase (Sande 2019; Sande et al. 2020),10 where phase heads are assumed to be spelled out together with their complements.11 The assumption that phase heads are spelled out together with their complements is non-standard, and we need not adopt it here. While there is a possible adequate analysis of the Kaqchikel facts (and the Blackfoot facts in (Section 5)) that does assume phase heads are spelled out together with their complements, we choose to work under the more standard assumption that phase heads trigger spell-out of their complements.

The analysis of high-attaching prefixes as phase heads is supported by their morphosyntactic functions, which correspond to those that we expect from phase heads. Phase boundaries are predicted to include syntactic nodes v/Voice, C, and D, as well as categorizing heads (or derivational morphemes) (Arad 2003; Chomsky 2001, 2004; Embick 2010; Marvin 2002). High-attaching prefixes in Kaqchikel include derivational morphology like the agentive, as well as absolutive prefixes. Aspectual morphemes and ergative possessive prefixes, on the other hand, are low-attaching. The difference between absolutive prefixes and other agreement prefixes may seem unexpected in a phase-based account, but see Coon et al. (2021) on the different extraction properties of ergative and absolutive arguments in the Kichean branch of Mayan (which includes Kaqchikel). They suggest that ergative morphology is lower in the syntactic structure than absolutive morphology, accounting for the extraction asymmetries.12 The different syntactic positions of ergative and absolutive morphology also account for their different patterning here: absolutive markers are phase heads (or are in the specifier of a null phase head), while other agreement markers are not.

Example vocabulary items in CbP for a root, a high-attaching prefix, and a low-attaching prefix are given in (25).

- (25)

- Kaqchikel vocabulary items

- a.

- b.

- [agt]

- c.

- [3sg.erg]

Note that there is no morpheme-specific phonology necessary to get the Kaqchikel facts to come out, so none of the vocabulary items is associated with a . However, the use of prosodic specifications shown here differs slightly from previous assumptions in CbP (Sande and Jenks 2018; Sande et al. 2020), where morpheme-specific prosodic subcategorization frames would also build or specify prosodic structure. For example, a listed as -X ] would specify that the relevant morpheme is a suffix within a prosodic word, and ]-X would result in suffixation outside of a prosodic word (a clitic, perhaps). Here, Tri-P mapping systematically tells us how prosodic structure is built, so we only need specify a morpheme’s relationship to prosodic structure in the Vocabulary Item if it is exceptional (see (44) in Section 5 for an example from Blackfoot). Note that the analysis provided by Bennett (2018) crucially relies on high- and low-attaching prefixes having different prosodic subcategorization requirements. However, that is not the case in our analysis, as in (25b) versus (25c).

Low-attaching prefixes do not trigger spell-out or phonological evaluation, since they are not phase heads. When a high-attaching prefix is added in the syntax, its complement is spelled out as a prosodic word, and if vowel initial, surfaces with an initial glottal stop, as in the tableau in (26), which shows phonological evaluation of the first spell-out domain of (23c). When the agentive prefix, a derivational categorizing head n, attaches to the vowel-initial root ‘month’, the agentive prefix itself is not spelled out, but the root is.

- (26)

- Derivation of ʔaχ=ʔikʔ, ‘domestic worker’

/ikʔ/ Onset Max Dep a. [ ikʔ] *! b. [ kʔ] *! c. ☞[ ʔikʔ] *

When a second high-attaching prefix is added in the syntactic structure, such as an absolutive subject prefix, its complement is spelled out. The complement includes the previously spelled out [ʔikʔ], as well as the agentive morpheme. Because the agentive morpheme is vowel-initial and now is at the beginning of the spell-out domain, we again see glottal stop insertion, as in (27). Morpheme-specific requirements of morphemes introduced in previous phases are no longer available to the phonology.

- (27)

- Derivation of ʔin=ʔaχ=ʔikʔ, ‘I am a domestic worker’ (to be revised)

/aχ-[ω ʔikʔ]/ Onset Max Dep a. [ aχ. [ω ʔikʔ]] *! b. [ ʔa.χ [ω ikʔ]] *! c.☞[ ʔaχ. [ω ʔikʔ]] *

Because the output of the previously spelled out phase, ʔikʔ is part of the input in (27), deleting the initial glottal stop on this root violates Max, ruling out a candidate like (27b). The optimal candidate is one that does not delete output structure, but where every syllable has an onset, as in (27c), even if that means inserting another glottal stop.

Let us compare (27), where the outputs include recursive words, with (28), where we assume a constraint against recursive words. We see that the two have the same segmental result; however, recursive words are not optimal in (28). Whether word-level recursion is banned with a highly ranked constraint or some fundamental, inviolable principle, an issue discussed further in Section 6, (28) shows that recursive words are not necessary to derive the optimal output.

- (28)

- Derivation of ʔin=ʔaχ=ʔikʔ, ‘I am a domestic worker’

/aχ-[ωʔikʔ]/ *Recursive- Onset Max Dep a. [ aχ.ʔikʔ] *! b. [ a.χikʔ] *! c. [ ʔaχ.[ωʔikʔ]] *! * d. ☞[ ʔaχ.ʔikʔ] *

We adopt the latter version of the analysis, without word-level recursion as in (28), in order to make the point that word-level recursion is not necessary to derive the Kaqchikel facts.

At the next phase boundary, the absolutive morpheme is spelled out. Its prosodic specification states that it must appear at the left edge of , so the only candidates considered are those where it is leftmost within a word.

- (29)

- [1sg.abs]

As it surfaces at the beginning of the prosodic domain, the optimal candidate is one that shows glottal stop insertion, much like in (27). The result is what appears to be recursion of glottal stop insertion at the word level, ʔin=ʔaχ=ʔikʔ but in actuality the multiple insertion is due to multiple instances of spell-out at syntactic phase boundaries.

On this analysis, the apparent recursive word effects in Kaqchikel are just that: apparent. They are due to multiple instances of spell-out, determined by syntactic phase boundaries. The resulting structure may still contain recursive words, as in (27), but need not, as in (28). Instead, the best generalization about the position of glottal stop insertion is that a syntactic phase that begins with a vowel in the input is preceded by a glottal stop in the output. This case study is one of very few that shows properties of word-level recursion, and it can be analyzed without a recursive prosodic structure. Perhaps, then, there is a universal ban on word-level recursion, and this case is best analyzed without recursion as in (28).

Many cases of multiple different prosodic word levels, such as minimal and maximal words or clitic groups, can also be analyzed in CbP+Tri-P, though with morpheme-specific phonological effects (s) associated with different syntactic domains. These are discussed further in Section 6.

One question that arises in our model is whether non-regular phonology should be accounted for as domain-sensitive boundary effects, or as morpheme-specific cophonologies. We propose that the difference between prosodic and morpheme-specific phenomena should be determined based on whether every instance of some domain is subject to a particular phonological process versus only the domain containing a particular morpheme being subject to a phonological process. The latter would justify a morpheme-specific cophonology. Kaqchikel glottal-stop insertion is an example of the former, where every prefixal syntactic phase head correlates with left-edge glottal-stop insertion. If it was just one or two phase heads, but not all of them, we would analyze this as a cophonology as opposed to a general left-edge process within a spell-out domain. For clear examples of morpheme-specific effects that are not general across all prosodic words, see prior work in Cophonologies by Phase (Sande 2019; Sande et al. 2020).

5. Blackfoot Embedded Roots

5.1. Blackfoot Data

In Blackfoot (Algonquian), Weber (2020) also argues that there is evidence of prosodic word-level recursion: [[]]. Verb stems in Blackfoot are morphologically complex, allowing more than one a-categorical root.13 Two types of are described: obligatory High Roots and optional Low Roots. High Roots are XP-adjoined to vP or VP as in (30a). Though an adjunct, a High Root is required for both transitive and intransitive verbs to complete event semantics and the first phase. A Low Root is either (a) head-adjoined to v0 or V0 as in (30b) or (b) an XP-adjoined that does not complete event semantics. High and Low Roots demonstrate different phonological properties. All examples here come from Weber (2020). Unless otherwise cited, they come from Weber’s own fieldwork.14

- (30)

- Root Adjunction to XP or X

Consonant-initial Low Roots demonstrate an epenthesis process following consonants to satisfy syllabification requirements. An [o] is epenthesized before a Low Root with an /o/ as its first underlying vowel as in /toji/ ’tail’ (31a).15 The same Low Root is seen surfacing unchanged in (31b) following a vowel:

- (31)

- a.

pi:n- otój -∅ -∅ -w NEG tail -AI -IND -PRX ‘wolverine’ - b.

á:wa -toj -â:piks:i -t -∅ wander -tail -throw/AI -2SG.IMP -CMD ‘wag your tail!’

An [i] is inserted in all other cases (32–33). In (32a), the Low Root /p/ ’by mouth’ surfaces with an epenthetic [i] following the final consonant in [ipon] ’cease.’ It surfaces as [p] after the final vowel in [ato] ’taste’ in (32b). In (33a), the Low Root /p/ ’tie’ surfaces with an epenthetic [i] following the final affricate in [ip:o

] ’secure.’ It surfaces as [p] after the final vowel in [amo] ‘gather.’

- (32)

- a.

â:- ipon -ip -i: -∅ -w =áji̥ FUT- cease -by.mouth.v -3SUB -IND -3 =OBV.SG ‘She will stop carrying him with her teeth.’ - b.

á:to -p -i: -∅ -w =aji̥ taste -by.mouth.v -3SUB -IND -3 =OBV.SG ‘he tasted him’ (Taylor 1969, p. 239)

- (33)

- a.

p:o -íp -ist -a: -∅ -wḁ secure -tie -v -AI -IND -3 ‘she wore braids’ - b.

amo -p -íst -a -n -i̥ gather -tie -v -AI -NMLZ -IN.SG ‘ceremonial bundle’

In contrast, vowel-initial Low Roots surface unchanged after consonants (34).

- (34)

â:k -xxp -im: -i: -∅ -w =áji̥ FUT -ASSOC -by.mind.v -3SUB -IND -3 =OBV.SG ‘she will associate him with something or someone’

After vowels, vowel-initial Low Roots undergo coalescence with the preceding vowel to resolve hiatus. Below, the same Low Root ‘by mind’ now follows a vowel-final High Root. The final /a/ of the root /sata/ ‘offended’ coalesces with the initial /i/ of /im:/ ‘by mind,’ and it surfaces as [έm:]

- (35)

sat -έm: -is -∅ (cf. /sata-im:-s-∅/) offended -by.mind.v -2SG:3.IMP -CMD ‘wish evil on him!’

High Roots show two relevant alternations in Blackfoot, depending on their location in the clause. First, initial glides delete when the High Root occurs clause-initially, but they surface unchanged when the High Root follows a prefix (36). As seen in (36a), the initial glide in /ja:t/ ’growl’ deletes. It surfaces with the underlying glide in (36b), though, following the imperfective prefix.

- (36)

- a.

a:t -ó: -t -∅ growl -AI -2SG.IMP -IMP ‘howl (as a dog)!’ - b.

á- ja:t -kin -a -∅ -wḁ IPFV- growl -throat -AI -IND -3 ‘she is growling.’

Second, initial stops surface when the High Root occurs clause-initially, but after a prefix they are subject to a combination of epenthesis and phonologically optimizing allomorphy. The epenthesis process is similar to the epenthesis observed with Low Roots, by default inserting an [i], but it is conditioned by the prosodic position of the left-edge of the High Root rather than by syllabification. In fact, the left edge of a High Root often occurs in the middle of a syllable. Ultimately, there are three surface variants of stop-initial High Roots when following a prefix: an initial epenthetic [i], root-internal gemination, and initial [oxw].

In (37), epenthesis applies. As seen in (37a), /pʊm:/ ‘transfer’ surfaces as [ipʊm:] following the future prefix. It surfaces unchanged in (37b):

- (37)

- a.

â:- ipʊ́m: -o -ji: -∅ -w =áji̥ FUT- transfer -v -3SUB -IND -3 =OBV.SG ‘he will transfer it to her.’ - b.

pʊm: -o -:s -∅ transfer -v -2SG:3.IMP -CMD ‘transfer (e.g., the medicine bundle) to him!’

Next, a set of lexically marked morphemes demonstrate root-internal gemination following a prefix (38). In (38a), /kipita/ surfaces as [ippit] following a future prefix.16 It surfaces unchanged in (38b). Weber (2020) analyzes this as phonologically optimizing suppletive allomorphy:

- (38)

- a.

â:- ippit -εːstaw -at -a -∅ -wḁ FUT- aged -grow -v -3OBJ -IND -3 ‘she will be raised by the elderly.’ - b.

kipitá -a:ki aged -woman.n ‘old woman’

Finally, a set of lexically marked morphemes demonstrate what Weber calls initial [oxw] allomorphs following a prefix (39). In (39a), /pʊm:/ ’buy’ surfaces as [xwpʊm:].17 It surfaces unchanged in (39b).

- (39)

- a.

â:k- xwpʊm: -a: -∅ -wḁ FUT- buy -AI -IND -3 ‘she will buy’ - b.

pʊm: -a: -t -∅ buy -AI -2.SG.IMP -CMD ‘buy!’

Additional High Roots in the verb complex yield layered application of the epenthesis process and/or phonologically optimizing allomorphy. In (40a), epenthesis applies twice, once at the left edge of each High Root in the embedded structure. /ko:tski/ ’extreme’ surfaces as [ikotski].18 While obscured at the surface, the root /sto/ also undergoes epenthesis. It is preceded by the imperfective prefix /á-/ in the underlying form. Epenthesis applies and forms [isto], and then the prefix and epenthetic [i] coalesce to ultimately surface as [εs:to]. The same roots are seen clause-initially in (40b)–(40c). As indicated below, the root /sto/ is almost always produced without the initial [i], though there is some inter-speaker variation.

- (40)

- a.

â:- ikotski- εsto -ji -∅ -wḁ (c.f. /â:k-ko:tski-á-sto-ji-∅-wa/) FUT- extreme- cold.IPFV -II -IND -3 ‘it will be extremely cold.’ - b.

ko:tski- έ:saj- â:ki: -∅ -wḁ extreme- IPFV- lie.AI.IPFV- woman -IND -3 ‘she is a terrible liar.’ - c.

(i)sto -jí: -∅ -wḁ cold -II -IND -3 ‘it is/was cold.’

5.2. Previous Analysis: Recursive Words

Weber adopts a recursive word analysis of the Blackfoot data. Low Root epenthesis is a word-internal process, while the High Root alternations described in the previous section then fall out from interacting edge-based constraints at the word- and phrase-levels. Stops are disallowed at the left edge of the word, but they are allowed at the left edge of the phonological phrase. Likewise, glides are disallowed at the left edge of the phrase, but word-initial glides may surface unchanged when the phrase and word boundaries are misaligned.

Weber argues for a modification of Match Theory’s (Selkirk 2011) definitions based on phases. While Selkirk argues that the X0, XP, CP correspond with the , , and , respectively, this is found to be too restrictive for Blackfoot. Thus, the following definitions are given.19 Phase I is understood to be when event semantics is complete (like in Ramchand 2008), and it corresponds to the v*P phase. Given the recursive account, a verb complex with only one High Root would correspond to a minimal prosodic word. Additional High Roots introduce more word-boundaries and also form prosodic words. Phase II is triggered by C.

- (41)

- Phase-based Correspondence in Blackfoot (Weber 2020, p. 15)

Phase II CP ⟷ PPh (phonological phrase) Phase I vP/VP ⟷ PWd (prosodic word) v*P ⟷ PWdmin (minimal prosodic word)

Weber argues that a recursive account is the only one that correctly accounts for the data in Blackfoot. Consider the following logical possibilities for the prosodification of embedded roots.20 Multiple High Roots exhibit the same patterns of allomorphy and edge effects at the left edge of the phonological word. Tree (b) is thus incorrect. There are no CP-internal domains of PPh-right edge effects (see Weber’s discussion of devoicing and degenerate syllables). Therefore, Tree (c) is incorrect. Weber concludes only Tree (a) provides an accurate account.

- (42)

- Potential Prosodic Structures in Blackfoot (Weber 2020, pp. 284–85)21

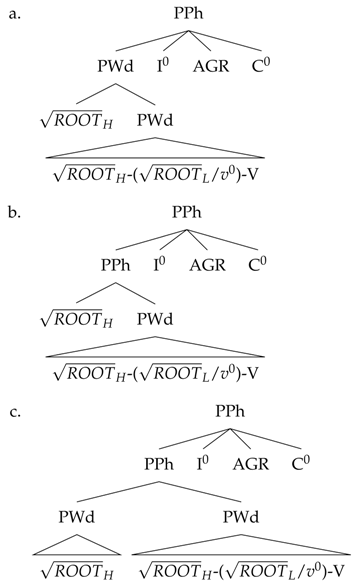

5.3. Updated (Non-Recursive) Analysis: Phase-Based Spell Out

Like Kaqchikel, we put forward an alternative analysis of Blackfoot that bypasses the need for recursive prosodic words. First, however, we must address Weber’s proposal that the full v*P phase corresponds with the phonological word and the VP phase corresponds with the phonological phrase. As originally proposed, Tri-P Mapping maps v*P phases as phonological phrases and CP phases as intonational phrases. Blackfoot is a particular challenge, as the current Tri-P definitions would not map anything in Blackfoot to a phonological word. Tri-P references morpheme-level phases (or those with categorizing heads), and Blackfoot’s a-categorical heads merge, definitionally, without categorizing heads. Just as Weber needed to revise previous definitions, we must too.

Rather than referencing specific types of phases (i.e., morpheme-level vs. clause-level), Tri-P’s definition of may be modified to reference phase size relative to others (43). The revised definition allows Tri-P to account for languages like Blackfoot and become less reliant on other theoretical models (i.e., Distributed Morphology).

- (43)

- Tri-P Word (Revised)The first, most embedded phase maps to .

Note that Weber’s account of the full CP mapping to also poses a challenge for Tri-P Mapping. C’s phase is defined as mapping to , but Weber requires that to map to a . One might consider revising all of Tri-P’s definitions in terms of relative size of phases (i.e., the smallest corresponds to the word, the next smallest the phrase, the next smallest the intonational phrase). It is not this simple, though, as and may exhibit recursion. Since the is the relevant constituent for our analysis, we leave the question of whether to revise the Tri-P definitions of and to future work. Weber notes that there is no literature about the intonational phrase in Blackfoot. Perhaps what is analyzed as the phrase is in fact an intonational phrase, and no revision to the higher Tri-P definitions is needed.

Returning to the Blackfoot analysis, we align with Weber in acknowledging that High Roots complete event semantics, thus closing out a phase. To reflect the semantic reality, we propose that there is a functional head that is a sister to each High Root. That functional head is a phase head, though the particular nature of that head is left to future work. Low Roots are not sister to a phase head, and at least one High Root is obligatory; thus, Low Roots will never occur at the left-edge of a phase and therefore are never subject to left-edge alternations.

We propose that High s bear a subcategorization frame which requires them to be both inside and at the left-edge of a PWd. An example Vocabulary Item for the root /ko:tski/ is given in (44). None of the other relevant vocabulary items are associated with or specifications:

- (44)

- ⟷

These morpheme-specific prosodic requirements then interact with phonological constraints to result in the cyclic application of edge-based processes but only one prosodic word. We focus our analysis on the High Root epenthesis facts and apparent recursive structure, and point readers to Weber (2020) for an analysis of the High Root suppletive allomorphy facts discussed in Section 5.1.

The following three tableaux show a step-wise derivation of example (40), where there are two High Roots.22 In (45), we see the stem spelled out, which includes the first High Root and suffixes. The optimal candidate is that which includes the initial epenthetic [i].

- (45)

- Derivation of /sto-ji-∅-wa/

/sto-ji-∅-wa/ *Recursive-ω *#C Dep *V: a. [ sto.ji.wa] *! ☞b. [ i.sto.ji.wa] *

The prosodic subcategorization requirement that the High Root /sto/ be inside at the left edge of a prosodic word is met at this stage. Candidates with alternate prosodifications are not considered because Tri-P specifies that the first, most embedded phase domain is mapped to a .

After the functional morpheme above the next High Root /ko:tski/ is added, its complement is spelled out. This second spell-out domain includes /ko:tski/, the imperfective /a-/, and the previously spelled out [stojiwa]. The *ai constraint ensures coalescence of the imperfective /a-/ and epenthetic [i].

- (46)

- Derivation of /ko:tski-á-[istojiwa]/

/ko:tski-á-[istojiwa]/ *Recursive-ω *#C Dep *V: *ai a. [ kot.ski.á.is.to.ji.wa] *! * b. [ i. kot.ski.á.is.to.ji.wa] * *! c. [ ko:t.ski.εs.to.ji.wa] *! * d. [ i.ko:t.ski.εs.to.ji.wa] * *! e. [ kot.ski.εs.to.ji.wa] *! ☞f. [ i.kot.ski.εs.to.ji.wa] * g. [ i.kot.ski [ εs.to.ji.wa]] *! *

At this second phase level, the morpheme-specific prosodic requirements of /sto/ are no longer available to the phonology, but the subcategorization requirement of /ko:tski/ is active and is met: it surfaces at the left edge of the prosodic word. The *Recursive- constraint prevents a recursive structure, which means that /sto/ is no longer at the left edge of a prosodic word. This is is not problematic for the analysis, since the morpheme-specific requirements of /sto/ are no longer active.23

After further inflectional affixes like the future /a:k-/ are added, the C head triggers spell-out, as in (47). Sequences of /ki/ surface as [i], which we motivate with a *ki constraint. The winning candidate then violates an Ident-Manner constraint, which is ranked below *ki.

- (47)

- Derivation of /á:k-[ikotεskistojiwa]/

/á:k-[ikotskiεstojiwa]/ *Recursive- *#C Dep *V: *ki Id-Manner a. [ á:k [ ikotskiεstojiwa]] *! * ☞b. [ â[ ikotskiεstojiwa]] * c. [ â[ ikotski[ εstojiwa]]] *!

As with Kaqchikel, the apparent recursion in Blackfoot can be analyzed without recursive structure, by mapping syntactic phase domains to prosodic structures and adhering to morpheme-specific prosodic requirements.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

We have shown that apparent word-level recursion in Kaqchikel and Blackfoot can be reanalyzed without recursion in a CbP + Tri-P account. This section presents unanswered questions regarding word-level recursion. Section 6.1 addresses whether intermediate prosodic domains such as the clitic group can be done away with on a CbP+Tri-P analysis. Section 6.2 addresses how to formally prevent word-level recursion. Section 6.3 presents further questions for future research, and Section 6.4 concludes.

6.1. Do We Still Need Distinct Intermediate Domains between Word and Phrase?

In Section 4 and Section 5, we reanalyze recursive prosodic words as multiple instances of spell-out, where spell-out domains are determined by syntactic structure, and phonological constraints interact with Tri-P mapping and morpheme-specific prosodic subcategorization. The result is a non-recursive structure. Additionally, in Section 5, we do away with the need for a distinction between minimal and . One question raised by this reanalysis is whether we can also be rid of other intermediate prosodic levels such as the clitic group or maximal word, both introduced in Section 2. It is likely that many such intermediate levels can be reanalyzed as due to cyclic spell-out plus morpheme-specific subcategorization requirements () or phonological constraint rankings ().

For example, in northern Italian, /s/ is voiced intervocalically within prosodic words, but not between clitics or between clitics and prosodic words: [cauz-ano] ‘they cause’, but [lo si [sala]] ‘he salts it for himself’ (Vogel 2009b, p. 66). Vogel analyzes clitics as being outside the prosodic word level, but inside a separate prosodic domain, the clitic group. In this process, there is clearly no word-level recursion, at least based on the definition in (2), since different phonological processes apply in each domain. However, an analysis similar to the Kaqchikel and Blackfoot analyses presented here is possible as long as clitics are associated with a morpheme-specific constraint ranking (). That ranking would require a faithfulness constraint like Ident to outrank a markedness constraint ensuring no voiceless /s/ between vowels. This ranking would only apply in the spell-out domain containing relevant clitics.

The question is whether one or two functional morphemes could be associated with the relevant ranking to derive the correct output in every case, or whether every clitic would need to be associated with this same ranking. If the latter, then an analysis that allows for an intermediate prosodic domain like a clitic group may in fact be preferred, as it would be more economical.

Further work is needed to determine exactly which phenomena can be reanalyzed in CbP+Tri-P, and which require intermediate prosodic levels.

One alternative analysis to consider here is whether all sub-word prosodic domains may be the result of lexical levels in a level-ordering framework (Bermúdez-Otero 1999; Kiparsky 1982; Mohanan 1982). In level-ordering theories, words are built in the lexicon and morphemes are grouped into levels or strata, where morphemes within each level or stratum are subject to a single set of phonological restrictions or processes. On this analysis, level-1 morphemes would be predicted to attach closest to the root, and would all be subject to one set of phonological rules or constraints, whereas level-2 morphemes are predicted to attach further from the root and be sensitive to a different phonological grammar. Another prediction of most level-ordering frameworks is that sub-word levels can by cyclic, while word- and phrase-levels are not cyclic (Bermúdez-Otero 1999, 2011, 2018; Booij and Rubach 1987; Kiparsky 1982; Pesetsky 1979).

While a level-ordering model may account for some cases of apparent (sub-)word level recursion, it cannot account for all of the cases discussed here. For example, in Kaqchikel (Bennett 2018), high- and low-attaching prefixes show different phonological properties with respect to gemination and glottalization, but they can be interleaved: HighPref-LowPref-HighPref-Root. This interleaving of low prefixes (level-1) and high prefixes (level-2) is not predicted by level ordering models (though see Mohanan 1982 on Malayalam compounds). Additionally, high-attaching prefixes are said to introduce word-boundaries in Bennett’s analysis, and word-levels are not expected to be cyclic in level-ordering theories. Thus, a level-ordering model would not actually predict the multiple glottal-stop insertion effects introduced by each high-affix in Kaqchikel.

6.2. What Prevents Recursive Words?

We have shown that two cases of possible recursion at the level can be reanalyzed without recursion. We have also proposed that word-level recursion is universally banned, since the very few convincing cases of it can be reanalyzed without it. Here, we begin to address the question of how the phonological grammar bans word-level recursion. What formal mechanism prevents word-level recursion?

The first option we consider is that a ban on recursive words is a standard markedness constraint in a constraint-based framework of phonological evaluation. On this approach, it would be coincidental that no language needs to be analyzed as showing recursive words in the output. Since the restriction on recursive words seems to be universal, rather than a tendency, this approach is not satisfactory.

An alternative is to adopt a modified constraint-based theory where not all constraints are violable. On this analysis, there would be a subset of (markedness) constraints that are universally upheld that are undominated in all human languages. A constraint against recursive words would fall within this set, explaining their cross-linguistic absence. Other possible universals that may be ensured with universally undominated, inviolable constraints include those discussed by Hyman (2008).

A third possibility is that there is a different formal mechanism for building s than for building s or s. In a lexicalist account, this difference would be trivial to implement, since words are built in a different module than larger structure. In fact, in any model where a separate morphological module of grammar is responsible for building words, while a syntactic module builds higher levels of structure, this difference would be easily implemented (cf. Vogel’s 2019 top-down versus bottom-up distinction). However, in a model like Distributed Morphology, where words and phrases are built simultaneously with syntactic structure, ideally, a single set of mapping procedures could build s, s, and s (Miller 2018).

In our analyses in Section 4 and Section 5, we adopt the second option: *Recursive- is a universally undominated constraint. However, we acknowledge that the other options presented here are possible alternatives, and we leave the best analysis of why recursion at the word level is universally banned for future work. The important point for this paper is that a formal mechanism blocks prosodic words from being recursive, since we have yet to find a data set that requires recursive prosodic words.

One may wonder whether a formal explanation of the lack of recursive words is needed at all. Perhaps a functional explanation is sufficient. A functional explanation would assert that phonological universals exist due to pressures external to the phonological system itself. For recursion in particular, recursive words may be systematically absent because they are difficult to process or learn. Evidence has shown that recursion, and specifically unbounded recursion, may not be necessary or desired in linguistic models based on language processing data (Christiansen 1992; Christiansen and MacDonald 2009). Children show knowledge of prosodic boundaries very early in language learning (Gerken 1996). Recursion, and specifically recursion of prosodic words, may make it more difficult for language learners to distinguish one word from the next, adding pressure for words not to be recursive. As far as we know, there have been no processing or acquisition studies of word-level recursion, though this would be a fruitful area for research and would certainly shed light on a cross-linguistic explanation for the lack of word-level recursion.

6.3. Questions for Future Work

The data and analyses presented in this paper raise some additional questions for future work.

For Blackfoot specifically, Weber (2021) expands on their original analysis of Blackfoot prosody to include all left-adjoining morphemes. Further research is needed to determine whether a syntactic phase-based analysis can explain these additional patterns in Blackfoot.

As discussed in Section 6.1, future work will determine which cross-linguistic phenomena can be accounted for without intermediate prosodic domains such as clitic groups, and which still require additional prosodic structure. Along the same lines, future work will determine whether a CbP+Tri-P analysis helps to account for recursion (or the lack of true recursion) in compound structures like those discussed in Section 2.1.

As mentioned in Section 6.2, we also leave for future work how to best formally implement a universal ban on recursion at the word level. We also acknowledge that the specific nature of the interaction between morpheme-specific CbP subcategorization requirements and Tri-P mapping requirements needs to be fully formalized based on additional empirical evidence.

Outside of word-level recursion, future work will examine the extent to which higher-level prosodic structure can also be analyzed as due to phase-based spell-out domains (Cheng and Downing 2016, 2021; Miller 2018; Sande 2019; Sande and Jenks 2018; Sande et al. 2020).

6.4. Conclusions

As shown in Section 4 and Section 5, the few known cases of apparent word-level recursion can be reanalyzed without recursive words, as long as prosody and phonology are spelled out at phase boundaries, and morpheme-specific cophonologies and prosodic requirements are permitted. In examining possible cases of word-level recursion, we further test the predictions of Cophonologies by Phase and Tri-P mapping.

In Kaqchikel, the position of glottal-stop insertion is shown to be predictable based on syntactic phase boundaries. Phonological evaluation applies at phase boundaries, and constraint interaction ensures that any phase that has an underlying initial vowel will surface with an initial glottal stop. Our analysis differs from Bennett’s (2018) analysis in two significant ways. First, whether high-attaching and low-attaching prefixes trigger glottal-stop-insertion is not due to different subcategorization frames, but is predicted by syntactic structure. Specifically, phase heads (high-attaching prefixes) trigger spell-out, which triggers left-edge glottal stop insertion. Second, our analysis does not require word-level recursion.

In Blackfoot, the position of epenthesis before High Roots is also determined by syntactically determined spell-out domains. Using a revised version of Tri-P’s definition of , which requires to be mapped from the first, most embedded phrases, instead of appealing to categorical heads, Tri-P is able to account for the full v*P in Blackfoot corresponding to the . Together with morpheme-specific prosodic requirements, our analysis predicts the position of epenthesis without appealing to word-level recursion.

In both cases, cyclic spell-out and application of phonology at phase boundaries result in the appearance of recursion. If our analysis is correct, we would not expect to find this kind of apparent recursive structure at multiple, nested, (sub-)word levels when those levels fail to align with syntactic phase boundaries.

The fact that it is possible to reanalyze the Blackfoot and Kaqchikel facts without recursion, using previously motivated theoretical tools, brings into question whether word-level recursion is ever necessary. In fact, future work will determine whether prosodic recursion at other levels of prosodic structure (such as the phonological phrase) can also be reanalyzed as due to spell-out at syntactic phase boundaries plus cophonologies. In addition, it is left for future work whether prosodic categories are best analyzed as emergent (as per Itô and Mester 2013) or universal. We specifically propose that recursion at the word level is universally prohibited, and that we only expect to see apparent word-level recursion at syntactic phase boundaries.

Author Contributions

T.L.M. and H.S. contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Natalie Weber, Ryan Bennett, and the audience at the Keio-ICU Linguistics Colloquium Series for their comments on this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1 | first person |

| 2 | second person |

| 3 | third person |

| A | transitive subject |

| ABS | absolutive |

| AGT | agent |

| AI | animate intransitive |

| ASSOC | associative |

| ASS | assertive |

| COND | conditional |

| CTR | contrastive |

| CMD | command |

| ERG | ergative |

| FUT | future |

| GEN | genitive |

| II | inanimative intransitive |

| IMP | imperative |

| IN | inanimate |

| IND | independent order |

| INF | infinitive |

| IPFV | imperfective |

| NEG | negative |

| NMLZ | nominalizer |

| NOM | nominative |

| NS | non-singular |

| OBV | obviative |

| PL | plural |

| POSS | possessive |

| PST | past |

| PRX | proximate |

| Q | question particle |

| S | sole argument of intransitives |

| SG | singular |

| SUB | subject |

| VOC | vocative |

References

- Abels, Klaus. 2012. Phases: An Essay on Cyclicity in Syntax. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 543. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Byron. 2015. Giving Reflexivity a Voice: Twin Reflexives in English. Ph.D. thesis, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, Arto. 2002. Morphologically conditioned phonological alternations. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 20: 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2003. Locality constraints on the interpretation of roots: The case of Hebrew denominal verbs. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21: 737–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Ryan. 2018. Recursive prosodic words in Kaqchikel (Mayan). Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo. 1999. Constraint interaction in Language Change: Quantity in English and Germanic. Ph.D. thesis, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo. 2011. Cyclicity. In The Blackwell Companion to Phonology. Edited by Marc van Oostendorp, Colin Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 4, pp. 2019–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo. 2018. Stratal phonology. In The Routledge Handbook of Phonological Theory. Edited by S. J. Hannahs and Anna Bosch. London: Routledge, pp. 100–34. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, Geert. 1996. Cliticization as prosodic integration: The case of Dutch. The Linguistic Review 13: 219–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, Geert, and Jerzy Rubach. 1984. Morphological and prosodic domains in lexical phonology. Phonology Yearbook 1: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, Geert, and Jerzy Rubach. 1987. Postcyclic versus postlexical rules in lexical phonology. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bošković, Željko. 2014. Now I’m a phase, now I’m not a phase: On the variability of phases with extraction and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 27–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, Željko. 2016. What is sent to spell-out is phases, not phasal complements. Linguistica 56: 25–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Lisa, and Laura Downing. 2021. Recursion and the definition of universal prosodic categories. Languages. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Lisa, and Laura J. Downing. 2007. The prosody and syntax of Zulu relative clauses. SOAS Papers in Linguistics 15: 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen, and Laura J. Downing. 2016. Phasal syntax= cyclic phonology? Syntax 19: 156–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A Life in Language. Edited by Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structures and Beyond. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Adriana Belletti. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 104–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory: Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Edited by Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 133–66. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Morten H. 1992. The (non)necessity of recursion in natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Indiana: Indiana University, pp. 665–70. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Morten H., and Maryellen C. MacDonald. 2009. A usage-based approach to recursion in sentence processing. Language Learning 59: 126–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Richard, and Christine Pittman. 2007. Affixation by phase: Inuktitut word-formation. Paper presented at the 81st Annual Meeting of the Linguistics Society of America, Anaheim, CA, USA, January 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Coon, Jessica, Nico Baier, and Theodore Levin. 2021. Mayan agent focus and the ergative extraction constraint: Facts and fictions revisited. Language 97. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Déchaine, Rose-Marie. 2002. On the Significance of (Non)-Augmented Roots. Toronto: Canadian Linguistic Association, University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Déchaine, Rose-Marie, and Natalie Weber. 2015. Head-merge, adjunct-merge, and the syntax of root categorisation. In Proceedings of the Poster Session of the 33rd West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, Simon Fraser University Working Papers in Linguistics. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, vol. 5, pp. 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Déchaine, Rose-Marie, and Natalie Weber. 2018. Root syntax: Evidence from Algonquian. In Papers of the Forty-Seventh Algonquian Conference. Edited by Monica Macaulay. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi, Yoshihito. 2003. Phonological Phrasing and Syntactic Derivation. Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi, Yoshihito. 2004a. Multiple spell-out, label-free syntax, and PF-interface. Explorations in English Linguistics 19: 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi, Yoshihito. 2004b. Restructuring of phonological phrases in Japanese and syntactic derivation. Manuscript, Kitami Institute of Technology, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, Laura J. 1998. Prosodic misalignment and reduplication. In Yearbook of Morphology 1997. Berlin: Springer, pp. 83–120. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, Laura J. 1999. Prosodic stem≠ prosodic word in Bantu. Studies on the Phonological Word 174: 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, Laura J., and Maxwell Kadenge. 2020. Re-placing PStem in the prosodic hierarchy. The Linguistic Review 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embick, David. 2010. Localism Versus Globalism in Morphology and Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Gerken, LouAnn. 1996. Prosodic structure in young children’s language production. Language 72: 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouskova, Maria. 2010. The phonology of boundaries and secondary stress in Russian compounds. The Linguistic Review 27: 387–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Green, Christopher R., and Michelle E. Morrison. 2016. Somali wordhood and its relationship to prosodic structure. Morphology 26: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guekguezian, Peter Ara. 2017a. Prosodic Recursion and Syntactic Cyclicity Inside the Word. Ph.D. thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Guekguezian, Peter Ara. 2017b. Templates as the interaction of recursive word structure and prosodic well-formedness. Phonology 34: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T. Alan. 1999. The phonological word: A review. In Studies on the Phonological Word. Edited by Tracy A. Hall and Ursula Kleinhenz. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 174, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Eunjoo. 1994. A prosodic analysis of Korean compounding. In Theoretical Issues in Korean Linguistics. Edited by Young-Key Kim-Renaud. Stanford: CSLI Publiciations for Stanford Linguistics Society, pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, Kristine A. 2007. Prosodic and grammatical domains in Limbu. Himalayan Linguistics 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, Kristine A. 2015. The prosodic word. In The Oxford Handbook of the Word. Edited by John R. Taylor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 221–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, Larry M. 2008. Universals in phonology. The Linguistic Review 25: 83–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkelas, Sharon. 1990. Prosodic Constituency in the Lexicon. New York: Garland Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Inkelas, Sharon, and Cheryl Zoll. 2005. Reduplication: Doubling in Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2007. Major phrase, focus intonation, multiple spell-out (MaP, FI, MSO). The Linguistic Review 24: 137–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2003. Weak layering and word binarity. In A New Century of Phonology and Phonological Theory. A Festschrift for Professor Shosuke Haraguchi on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Edited by Takeru Honma, Masao Okazaki, Toshiyuki Tabata and Shin-ichi Tanaka. Tokyo: Kaitakusha. [Google Scholar]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2007. Prosodic adjunction in Japanese compounds. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 55: 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2009a. The extended prosodic word. In Phonological Domains: Universals and Deviations. Edited by Janet Grijzenhout and Baris Kabak. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 135–94. [Google Scholar]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2009b. The onset of the prosodic word. In Phonological Argumentation: Essays on Evidence and Motivation. Edited by Steve Parker. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 227–60. [Google Scholar]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2012. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In Prosody Matters: Essays in Honor of Elisabeth Selkirk. Edited by Toni Borowski, Shigeto Kawahara, Takahito Shinya and Mariko Sugahara. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 280–303. [Google Scholar]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2013. Prosodic subcategories in Japanese. Lingua 124: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2015. The perfect prosodic word in Danish. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 38: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackendoff, Ray, and Steven Pinker. 2005. The nature of the language faculty and its implications for evolution of language (reply to fitch, hauser, and chomsky). Cognition 97: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]