Structural Changes in Bengali–English Bilingual Verbs through the Exploration of Bengali Films

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| 1. | Ora | park-ta | renovate | kor-ech-e |

| 3PL | park-CL | renovate | do-PFV-3P P | |

| ‘They have renovated the park.’ | ||||

| 2. | amra | tɔkhon | discussion | kor-chi-lam |

| 1PL | then | discussion | do-PROG-PST.1P | |

| ‘We were discussing then…’ | ||||

2. Background of Bengali and English Use in India

3. Methodology

Coding and Data Analysis

4. Complex Verb Constructions in Bengali

| 3. | she | gach | theke | por-ech-e | (simple verb) |

| 3SG | tree | from | fall-PFV-3P | ||

| ‘He/She has fallen from the tree.’ (Thompson 2010) | |||||

4.1. Monolingual Complex Verbs

- (N(Beng) + kᴐra/hᴐwa ‘do’/’be’)

| 4.a. | robi | lok-er | ɔnek | upokar | kor-ech-e | (N+‘do’) | |||||||

| Robi | people-GEN | much | help | do-PFV-3P | |||||||||

| ‘Robi has helped people a lot.’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | bæpar-ta | na | jene | jiggesh | kor-e | bosh-ech-i | (N+‘do’+V) | ||||||

| thing-DEF | NEG | knowing | question | do-PFV.PTCP | sit-PFV-1P | ||||||||

| ‘Without knowing, (I) suddenly (and unintentionally) asked him/her about the thing.’ | |||||||||||||

| c. | uni | amar | theke | shahajjo | ni-ech-e-n | (O V) |

| 3SG.HON | 1SG.GEN | from | help | take-PFV-3P-HON | ||

| ‘He/She has taken help from me.’ | ||||||

4.2. Bilingual Complex Verbs

- (N(Eng) + kᴐra/hᴐwa ‘do’/’be’; V(Eng) + kᴐra/hᴐwa ‘do’/’be’;

- N/V(Eng) + kᴐra/hᴐwa ‘do’/’be’)

| 5a. | shei | moment-e | operation | kor-l-o | (N(Eng)+’do’) | |||||||||||||||||||

| that | moment-LOC | operation | do-PST-3P | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘In that moment, (he) did the operation (surgery).’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | tui | o-r | shɔŋge | shopping | kor-b-i? | (Verbal noun(Eng)+’do’) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2SG | 3SG-GEN | with | shopping | do-FUT-2P | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘You will be shopping with her?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | cinema-ta | je | bhabe | build up | kor-echil-o | (Phrasal V(Eng)+’do’) | ||||||||||||||||||

| cinema-DEF | COMP | way | build up | do-PST.PFV-3P | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The way they had built up the movie…….’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | ora | bol-ech-e | application-ta | renew | kor-b-e | (V(Eng)+’do’) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3PL | say-PFV-3P | application-DEF | renew | do-FUT-3P | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘They said (they) would renew the application.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

4.3. Literature Review on Bilingual Complex Verbs

5. Analysis of BCV Use in the Bengali Films

5.1. Distribution of Complex Verbs in the Films of the Three Decades

5.1.1. Distribution of Complex Verbs in the Films of 1970s

| 6. | aapni | ei | shɔb | tribes der ke | study korechen |

| 2SG.HON | DEM | all | tribes PL ACC | study do-PFV.3P-HON | |

| ‘You have studied all of these tribes/You have done studies on all of these tribes.’ | |||||

5.1.2. Distribution of Complex Verbs in the Films of 1990s

5.1.3. Distribution of Complex Verbs in the Films post-2010

5.2. Qualitative Examination of Bilingual Complex Verb Use in the Films of the Three Decades

5.3. Discussion of the Results

| 7a. | tomake | bhalo | bashi | sheta | ɔsshikar | korchi na | (N(Beng)+’do’) | |||||||||

| 2SG-ACC | good | love-PRS.1P | that | denial | do-PRS-1P-NEG | |||||||||||

| ‘(I) am not denying that I love you.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | tui | to | baar baar | deny | kor-e | jacchish | (V(Eng)+’do’) | |||||||||

| 2SG | FOC | constantly | deny | do-PFV.PTCP | do-PRS.PROG-3P | |||||||||||

| ‘You are constantly denying it.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| c. | chatro-ta | accusation-ta-ke | denial | kor-ech-e | (N(Eng)+’do’) | |||||||||||

| Student-DEF | accusation-DEF-ACC | deny | do-PFV-3P | |||||||||||||

| ‘The student has denied the accusation.’ | ||||||||||||||||

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kachru, B.B. The Englishization of Hindi: Language rivalry and language change. In Linguistic Method: Papers in Honor of Herbert Penzl; Gerald, F., Rauch, C.I., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyter: The Hague, the Netherlands, 1978; pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B.B. Toward Structuring code-mixing: An Indian perspective. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. (Aspects of sociolinguistics in South Asia). 1978, 16, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaine, S. The syntax and semantics of the code-mixed compound verb in Panjabi/English bilingual discourse. In Languages and Linguistics: The Interdependence of Theory, Data and Application; Tannen, D., Alatis, J.E., Eds.; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai, E. The anglicized Indian languages: A case study of code-mixing. Int. J. Dravid. Linguist. 1978, 7, 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai, E. The language factor in codemixing. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 1989, 75, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, M.S. English borrowings in educated Tamil. In Studies in Indian Linguistics; Krishnamurti, B., Ed.; Center of Advanced Study in Linguistics: Annamalainagar, India, 1968; pp. 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, T. Bangla. In Facts About the World’s Languages: An Encyclopeia of the World’s Major Languages, Past and Present; Garry, J., Rubino, C., Eds.; Wilson: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, A. Two in one. In Bilingual speech of Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands; Tilburg University Press: Tilburg, the Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken, P. Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken, P. From Colombo to Athens: Areal and Universalist Perspectives on Bilingual Compound Verbs. Languages 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, S.; Wohlegemuth, J. Loan Verbs in a Typological Perspective; Romanisation Worldwide: Bremen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth, J. A Typology of Verbal Borrowings; Mouton de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Si, A. A diachronic investigation of Hindi-English code-switching using Bollywood film scripts. Int. J. Biling. 2011, 15, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, T.K.; Ritchie, W.C. The Bilingual mind and linguistic creativity. J. Creative Commun. 2008, 3, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, T.K. English and the vernaculars of India: Contact and change. Appl. Linguist. 1982, 3, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailaja, P. Indian English, 1st ed.; Dialects of English; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2009; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C. The History of Bengal: From the First Mohammedan Invasion until the Virtual Conquest of that Country by the English, A.D. 1757; Bangabasi: Calcutta, India, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.K. The Raj and the Bengali People; Firma KLM: Kolkata, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, T.K.; Richie, W.C. Bilingualism in South Asia. In The Handbook of Bilingualism; Bhatia, T.K., Ritchie, W.C., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 780–807. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, S. Rethinking English: Essays in Literature, Language, History; Oxford University Press: Delhi, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Agradoot. Chadmabeshi; Dutta, S.; Laha, B. Productions; Angel Digital Video: Calcutta, India, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, D. Basanta Bilap; Sonali Productions; Angel Digital Video: Calcutta, India, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S. Agantuk (The Stranger); DD Productions; Mr Bongo: Calcutta, India, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, R. Unishe April (19th April); Spandan films; Angel Digital Video: Calcutta, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, J.B.; Bhaumik, M. Maach Mishti & More; Mojo Productions & Tripod Entertainment: Kolkata, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, P. Hawa Badal; Workshop Productions; RTC Entertainment Private Limited: Kolkata, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sailaja, P. Indian English: Features and sociolinguistic aspects. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2012, 6, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, P.E. The Compound Verb in Hindi; Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Abbi, A.; Gopalakrishnan, D. Semantics of explicator compound verbs in South Asian languages. Lang. Sci. 1991, 13, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M. The Light Verb Jungle. Available online: http://ling.sprachwiss.unikonstanz.de/pages/home/butt/main/papers/harvard-work.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2015).

- Butt, M. The Light Verb Jungle: Still hacking away. In Complex Predicates; Mengistu, A., Baker, B., Harvey, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 48–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, H.R. Bengali: A Comprehensive Grammar; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Chakrabarti, D.; Sharma, V.M. Complex predicates in Indian languages and wordnets. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2006, 40, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. The internal grammar of compound verbs in Bangla. Indian Linguist. 1977, 38, 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand, G. Complex predicate formations in Bangla. In Proceedings of the Ninth West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 443–452.

- Basu, D. Syntax-Semantics Issues for Multiple Event Clauses in Bangla. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, T. Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them? In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 47–62.

- Moravcsik, E. Verb borrowing. Wien. Linguist. Gaz. 1975, 8, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, M.; University of Michigan. Personal Communication, 2015.

- Chatterjee, T. Bilingualism, Language Contact and Change: The Case of Bengali and English in India. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balam, O. Code-switching and linguistic evolution: The case of 'Hacer + V' in Orange Walk, Northern Belize. Leng. Migr. 2015, 7, 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Balam, O. Mixed Verbs in contact Spanish: Patterns of Use among Emergent and Dynamic Bilinguals. Languages 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1The recipient language, which integrates the non-native lexical element.

- 2Bengal Province was partitioned to create West and East Bengal in 1905 by the British administration in India. East Bengal Province became a part of Pakistan in 1947 (when India gained independence and Pakistan was born out of India), and came to be identified as East Pakistan. In 1971, East Pakistan seceded from Pakistan and became a new country, Bangladesh.

- 3This generalization is surprising, given that in some languages verbs can be borrowed as verbs, such as French Quebecois verbs such as tier ‘to tie (one’s shoe laces)’ + French infinitival suffix –er. It’s usually presented as a borrowing from English due to phonological adaptation, but it is a case of a verb being borrowed as a verb (Marlyse Baptista, p.c. [39]).

| Verb Types | Sub Types | Components of Verbs | Examples of Each Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | Gloss | Translation | |||

| Simple Verbs | 1 verb | bɔla | speak | ‘to speak’ | |

| Monolingual Complex Verbs | Conjunct verbs | N + kɔra/hɔwa N + kɔra/hɔwa + (V) | bikri kɔra jiggesh kore newa | sale do question do take | ‘to sell’ ‘to ask for oneself’ |

| Compound verbs | V + V | khe newa | eat take | ‘to eat for oneself’ | |

| Bilingual Complex Verbs | Conjunct verbs | N (Eng) + kɔra/hɔwa N (Eng) + kɔra/hɔwa + (V) | drawing kɔra manage kore jawa | drawing do manage do go | ‘to draw’ ‘to manage continuously’ |

| Compound verbs | V (Eng) + kɔra/hɔwa V (Eng) + kɔra/hɔwa + (V) | deny kɔra decide kore phæla | deny do decide do throw | ‘to deny’ ‘to decide (completely)’ | |

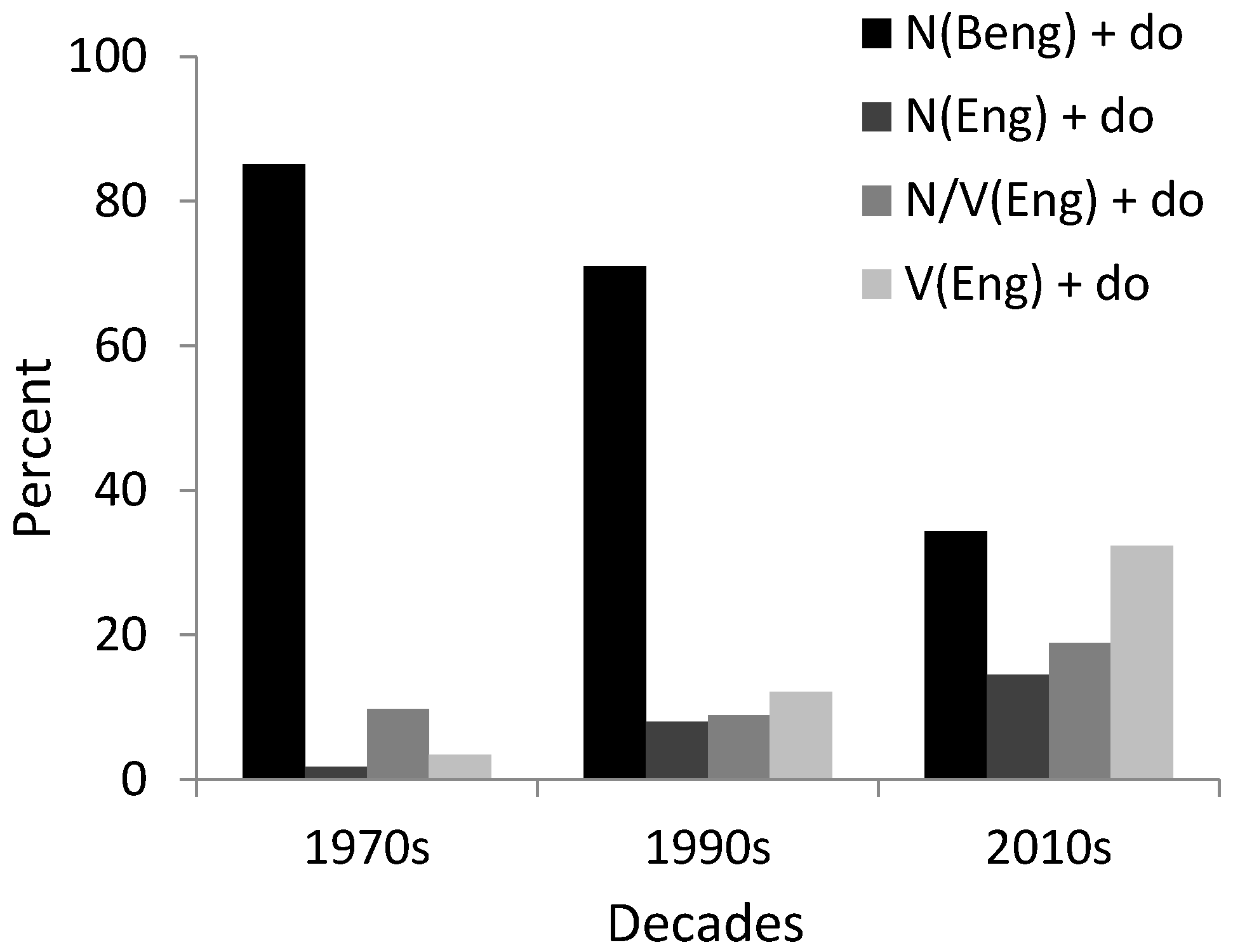

| Films of 1970s | Complex verbs N = 236 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(Beng) + ‘do’ % | N(Eng) + ‘do’ % | N/V(Eng) + ‘do’ % | V(Eng) + ‘do’ % | |

| 85.16 | 1.69 | 9.74 | 3.38 | |

| Films of 1990s | Complex verbs N = 214 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(Beng) + ‘do’ % | N(Eng) + ‘do’ % | N/V(Eng) + ‘do’ % | V(Eng) + ‘do’ % | |

| 71.02 | 7.94 | 8.87 | 12.14 | |

| Films of 2010s | Complex verbs N = 297 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(Beng) + ‘do’ % | N(Eng) + ‘do’ % | N/V(Eng) + ‘do’ % | (Eng) + ‘do’ % | |

| 34.34 | 14.47 | 18.87 | 32.32 | |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatterjee, T. Structural Changes in Bengali–English Bilingual Verbs through the Exploration of Bengali Films. Languages 2016, 1, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages1010005

Chatterjee T. Structural Changes in Bengali–English Bilingual Verbs through the Exploration of Bengali Films. Languages. 2016; 1(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages1010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatterjee, Tridha. 2016. "Structural Changes in Bengali–English Bilingual Verbs through the Exploration of Bengali Films" Languages 1, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages1010005

APA StyleChatterjee, T. (2016). Structural Changes in Bengali–English Bilingual Verbs through the Exploration of Bengali Films. Languages, 1(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages1010005