Facile Interfacial Engineering of Mesoporous TiO2 for Low-Temperature Processed Perovskite Solar Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate Fabrication

2.2. PSC Fabrication

2.3. Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Levi, D.H.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Yoshita, M.; Ho-Baillie, A.W. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 54). Prog. Photovolt. 2019, 27, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Park, E.Y.; Moon, C.S.; Shin, T.J.; Yang, T.-Y.; Noh, J.H.; Seo, J. Efficient, stable and scalable perovskite solar cells using poly(3-hexylthiophene). Nature 2019, 567, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomo, F.D.; Zardetto, V.; D’Epifanio, A.; Pescetelli, S.; Matteocci, F.; Razza, S.; Di Carlo, A.; Licoccia, S.; Kessels, W.M.M.; Creatore, M.; et al. Flexible perovskite photovoltaic modules and solar cells based on atomic layer deposited compact layers and UV-irradiated TiO2 scaffolds on plastic substrates. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Q.; Wu, B.S.; Lin, G.H.; Xing, Z.; Li, S.H.; Deng, L.L.; Chen, D.C.; Yun, D.Q.; Xie, S.Y. Interfacing pristine C60 onto TiO2 for viable flexibility in perovskite solar cells by a low-temperature all-solution process. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Giacomo, F.D.; Zhang, D.; Shanmugam, S.; Senes, A.; Verhees, W.; Hadipour, A.; Galagan, Y.; Aernouts, T.; Veenstra, S.; et al. Highly efficient stable flexible perovskite solar cells with metal oxides nanoparticle charge extraction layers. Small 2018, 14, 1702775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dkhissi, Y.; Meyer, S.; Chen, D.; Weerasinghe, H.C.; Spiccia, L.; Cheng, Y.B.; Caruso, R.A. Stability comparison of perovskite solar cells based on zinc oxide an titania on polymer substrates. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Sato, W.; Shoyama, K.; Nakamura, E. Sulfamic acid-catalyzed lead perovskite formation for solar cell fabrication on glass or plastic substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5410–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.S.; Park, B.W.; Jung, E.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Lee, D.U.; Shin, S.S.; Seo, J.; Kim, E.K.; Noh, J.H.; et al. Iodide management in formamidinium-lead-halide–based perovskite layers for efficient solar cells. Science 2017, 356, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Park, E.Y.; Moon, C.S.; Shin, T.J.; Yang, T.Y.; Noh, J.H.; Seo, J. Efficient, stable and scalable perovskite solar cells using poly(3-hexylthiophene). Nature 2019, 567, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Noh, J.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Ryu, S.; Seo, J.; Seok, S.I. High-performance photovoltaic perovskite layers fabricated through intramolecular exchange. Science 2015, 348, 1234–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.; Teuscher, J.; Miyasaka, T.; Murakami, T.N.; Snaith, H.J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 2012, 338, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, K.; Sarwar, S.; Mehran, M.T. Current status of electron transport layers in perovskite solar cells: Materials and properties. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 17044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Tao, H.; Qin, P.; Ke, W.; Fang, G. Recent progress in electron transport layers for efficient perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huwang, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y. Low-temperature processed SnO2 compact layer by incorporating TiO2 layer toward efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 164, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, C.H.; Du, T.; Morbidoni, M.; Lin, C.T.; Xu, S.; Durrant, J.R.; McLachlan, M.A. ZnO-PCBM bilayers as electron transport layers in low-temperature processed perovskite solar cells. Sci. Bull. 2018, 63, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Hong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cai, M.; Song, T.B.; Chen, C.C.; Lu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Low-temperature solution-processed perovskite solar cells with high efficiency and flexibility. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1674–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.S.; Yang, W.S.; Noh, J.H.; Suk, J.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Seong, W.M.; Seok, S.I. High-performance flexible perovskite solar cells exploiting Zn2SnO4 prepared in solution below 100 °C. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.M.; Lee, M.M.; Hey, A.; Snaith, H.J. Low-temperature processed meso-superstructured to thin-film perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1739–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, Y.Y.; Shin, H.W.; Han, G.S.; Hong, J.S.; Mahmood, K.; Ahn, T.K.; Joo, Y.C.; Hong, K.S.; et al. Highly efficient and bending durable perovskite solar cells: Toward a wearable power source. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Naka, S.; Okada, H. Annealing effect of E-beam evaporated TiO2 films and their performance in perovskite solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2018, 360, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, R.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.F.; Li, C. High efficiency flexible perovskite solar cells using superior low temperature TiO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3208–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Dutta, V. Low-temperature synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles and preparation of TiO2 thin films by spray deposition. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2007, 91, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Conings, B.; Baeten, L.; Jacobs, T.; Dera, R.; D’Haen, J.; Manca, J.; Boyen, H.G. An easy-to-fabricate low-temperature TiO2 electron collection layer for high efficiency planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. APL Mater. 2014, 2, 081505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, Q.; Iqbal, Y.; Pal, B.; Lowe, A.; Jose, R. Tin oxide as an emerging electron transport medium in perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2018, 179, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliman, P.J.; Muslem, D.K.; Jones, E.W.; Connell, A.; Davies, M.L.; Charbonneau, C.; Carnie, M.J.; Worsley, D.A. Low temperature sintering of binder-containing TiO2/metal peroxide pastes for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 11134–11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.L.; Yao, D.S.; Gu, X.O.; Song, J.; Qiang, Y.H. Enhancing current density of perovskite solar cells using TiO2-ZrO2 composite scaffold layer. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2016, 56, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wu, J.; Lan, F.; Tao, Q.; Gao, D.; Li, G. Enhancing the performance of planar organo-lead halide perovskite solar cells by using a mixed halide source. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazaki, J.; Segawa, H. Evolution of organometal halide solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2018, 35, 74–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Nattestad, A.; Yu, H.; Bai, Y.; Wang, L.; Dou, S.X.; Kim, J.H. Highly connected hierarchical textured TiO2 spheres as photoanodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 8902–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Murakami, T.N.; Comte, P.; Liska, P.; Grätzel, C.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M. Fabrication of thin film dye sensitized solar cells with sola to electric power conversion efficiency over 10%. Thin Solid Films 2008, 516, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

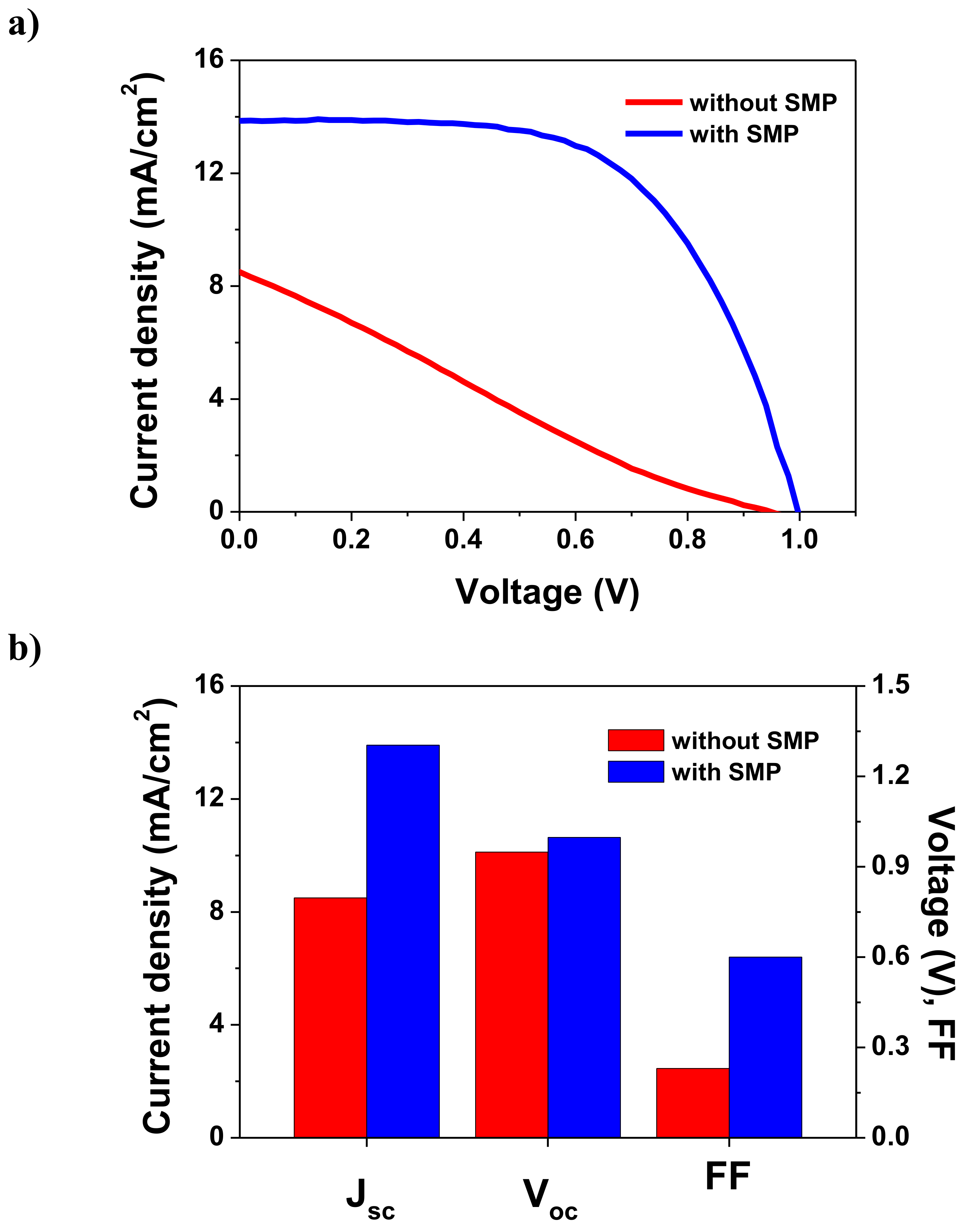

| TiO2 Sintering Temperature (°C) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (V) | FF | PCE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 | 20.61 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 13.67 |

| 450 | 20.46 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 13.49 |

| 350 | 19.23 | 1.03 | 0.68 | 13.45 |

| 250 | 13.20 | 0.97 | 0.52 | 6.63 |

| 150 (without SMP) | 8.50 | 0.95 | 0.23 | 1.85 |

| 150 (with SMP) | 13.86 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 8.27 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nam, J.; Nam, I.; Song, E.-J.; Kwon, J.-D.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.S.; Jo, S. Facile Interfacial Engineering of Mesoporous TiO2 for Low-Temperature Processed Perovskite Solar Cells. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9091220

Nam J, Nam I, Song E-J, Kwon J-D, Kim J, Kim CS, Jo S. Facile Interfacial Engineering of Mesoporous TiO2 for Low-Temperature Processed Perovskite Solar Cells. Nanomaterials. 2019; 9(9):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9091220

Chicago/Turabian StyleNam, Jiyoon, Inje Nam, Eun-Jin Song, Jung-Dae Kwon, Jongbok Kim, Chang Su Kim, and Sungjin Jo. 2019. "Facile Interfacial Engineering of Mesoporous TiO2 for Low-Temperature Processed Perovskite Solar Cells" Nanomaterials 9, no. 9: 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9091220