Abstract

The Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ), originally written in the German language, was translated and validated into 11 languages, but not Latin languages, such as Brazilian Portuguese. This study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of the SpNQ after translation and transcultural adaptation to the Portuguese language, identifying unmet spiritual needs in a sample of patients living with HIV in Brazil. This pioneering study conformed a four-factor structure of 20 items, differentiating Religious Needs (α = 0.887), Giving/Generativity Needs (α = 0.848), Inner Peace (α = 0.813) and a new item: Family Support Needs (α = 0.778). The Brazilian version of the SpNQ (SpNQ-BR) had good internal validity criteria and can be used for research of the spiritual needs for Brazilian patients. The cross-cultural adaptation and comparison with previous studies showed that the SpNQ is sensitive to the cultural characteristics of different countries.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines a four-fold approach as a health concept to assess individual and community well-being that includes biological, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects (). Among them, spirituality/religiosity has been deeply studied in the last decade and its positive effects on health are well established (). Spirituality is defined as “dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred, expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices” (). A further, rather broad definition assumes “spirituality as all attempts to find meaning, purpose, and hope in relation to the sacred or significant (which may have a secular, religious, philosophical, humanist, or personal dimension)”, and the related “spiritual practices have commitment to values, beliefs, practices, or philosophies which may have an impact on patients’ cognition, emotion, and behavior” (). Although spirituality is often used as an opposite dimension to religiosity, “spirituality can be found through religious engagement”, but also independent from specific religion “through an individual experience of the Divine, and/or through a connection to other people, the environment and the Sacred” ().

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is one of the chronic diseases that most mobilizes human beings from a bio-psycho-socio-spiritual view. People with this disease often face isolation, anxiety, stress, depression, stigma and discrimination, characterizing a situation where subjective, supportive, and resilience need to be addressed in physical and mental healthcare (). Although AIDS has figured in the scientific literature since 1981, study on the importance given to spirituality by AIDS patients has been directed toward the role of spirituality/religiosity (S/R) on coping with their illness (; ) or the disease in its final phase. Few studies have focused on the spiritual needs () of people living with HIV (PLHIV—seropositive patients who still do not show signs of disease progression), and none have been done in Brazil.

To help health services reflect the spiritual angle, several questionnaires have been proposed to check the relevance of S/R for chronic disease patients. The Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ) is one of the most widely used. Originally written in the German language, by (, ), this instrument can be used as a diagnostic instrument with 29 items and as a 20-item research instrument, which was validated in persons with chronic diseases, and also in (healthy) elderly and stressed people (). It avoids the exclusive use of religious terminology and is, thus, applicable also to persons living in secular societies and atheist/agnostic populations, relying on the bio-psycho-socio-spiritual or a “holistic” perspective of health. It has been translated into English, Italian, Polish, Danish, Chinese, Indonesian, Farsi, Croatian, and Lithuanian (), but not Latin languages, such as Brazilian Portuguese.

In this study, we aimed to identify spiritual needs in a sample of PLHIV in Brazil, translating SpNQ to the Portuguese Language and adapting it for cross-cultural purposes. It may highlight high-priority spiritual needs in a transdisciplinary perspective, contributing to a whole-person healthcare for these patients in Brazil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The cross-sectional, longitudinal validation study included application of the SpNQ-BR and a demographic information questionnaire (including age, educational status, gender and religious organizational or non-organizational practices) for 200 seropositive patients, randomly selected among patients who followed up at the AIDS Outpatient Clinic of the Medical School Hospital, located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This hospital is accredited as a National Aids Reference Center by the Brazilian Ministry of Health and it is the largest clinic with this specialty in Rio de Janeiro State. The inclusion criteria was to be older than or equal to 18 years of age, of all genders, HIV positive followed at Rio de Janeiro Federal State University Medical School HIV/AIDS Outpatient Clinic, to have the capacity to read, understand, fill out the instrument at the time of application. Patients with some level of clinical disorientation, unable to read, to understand, and to fill out the instrument, or those who refuse to sign the informed consent form were excluded. All participants were informed about confidentiality assurance and the purpose of the study and freely signed the informed consent form, consented to participate.

The study was carried out according to ethical principles in research and was approved by the Rio de Janeiro Federal State University (UNIRIO) Ethics Committee on Research in Human Beings (2.316.525/2017).

2.2. Questionnaire and Translation Process

To measure patients’ spiritual needs, we used the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ) (, ). In its primary version, it differentiates between four main factors:

- Religious Needs (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92), e.g., praying for and with others, praying alone, participating in a religious ceremony, reading spiritual/religious books, turning to a higher presence (e.g., God, angels);

- Existential Needs (Reflection/Meaning) (alpha = 0.82), e.g., reflecting on one’s life, talking with someone about the meaning of life/suffering, resolving open aspects in life, talking about the possibility of life after death, etc.;

- Need for Inner Peace (alpha = 0.82), e.g., wish to dwell in places of quietness and peace, plunge into the beauty of nature, finding inner peace, talking with others about fears and worries, turning to someone in a loving attitude;

- Need for Active Giving/Generativity (alpha = 0.74), e.g., active and autonomous intention to provide solace to someone, passing along one’s own life experiences to others, and to be assured that life was meaningful and of value.

All items were scored with respect to self-ascribed importance on a 4-point scale from disagreement to agreement (0—not at all; 1—somewhat; 2—very; 3—extremely). For all analyses, we used the mean scores of the respective scales described above; the higher the scores, the stronger the respective needs were.

Translation and validation of the questionnaire was performed using the World Health Organization recommendations for the translation and adaptation of instruments (). After reading other papers about SpNQ transcultural adaptation, we asked the author for authorization, and the transcultural translation procedure followed the steps described below:

- Step 1:Translation of the 27-item English version into Portuguese by two bilingual professionals, aware of the objectives of the study, resulting in two Portuguese versions of SpNQ.

- Step 2:The versions were compared by another bilingual researcher, resulting in a reconciled version in Portuguese.

- Step 3:The reconciled version was translated back into English by two other bilingual professionals, and the versions were compared by another bilingual researcher, resulting in an SpNQ reconciled version in English.

- Step 4:The English and Portuguese versions were sent to the author of the instrument for review and approval.

- Step 5:The final version was approved by the author and was revised for Portuguese grammar, punctuation and formatting, obtaining a translated version of SpNQ for the pre-test.

- Step 6:The translated instrument was presented to 26 outpatients in 4 Brazilian health services, and individual interviews were conducted with each of them to identify problems in understanding the instrument’s questions, obtaining the 27-item SpNQ Portuguese final version (27 SpNQ-BR).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency (Cronbach’s coefficient α) and factor analyses (principal component analysis using Varimax rotation with Kaiser’s normalization), as well as first order correlations, were computed using SPSS 21.0 and 23.0.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Data were collected in July, 2017. In the studied population, most were male (57%), with age ranging from 30–49 years old (57%) and 61% had a high school level education. Spiritists and religious organizational practices were the majority in the religious aspect (27%), as shown on Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and religion of HIV positive Brazilian participants (N = 200).

3.2. Validation of the Questionnaire

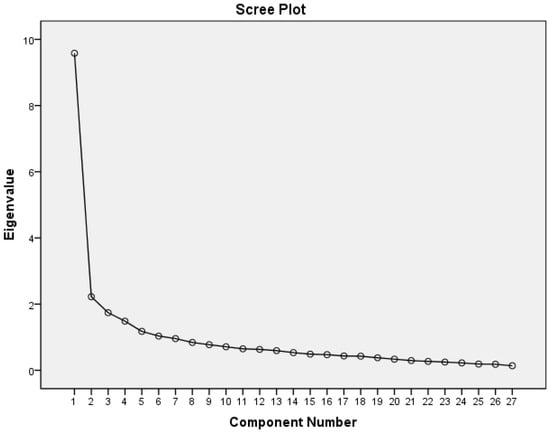

With KMO indexes = 0.89 and Bartlett’s sphericity test, X2(351) = 2775.405, p < 0.001 the item pool was suited for factor analysis. Together, they showed the association between items, which corroborated the factorial validity of the instrument and allowed us to continue analyses. The second step was the factorial analysis, fixing the number of factors to 4, as noted by (). To do so, we used the method for main components, with orthogonal rotation types. It is important to point out that, in fact, this solution presented the best statistical parameters, compared with other alternatives (example: Trifactorial, bifactorial, or unifactorial). The quadrifactorial structure obtained values (eigenvalues) of 9.58; 2.22; 1.74 and 1.48 (shown in Figure 1), explaining 55.6% of the total variance.

Figure 1.

Graphical distribution of eigen values of Spiritual Needs Questionnaire —Portuguese Version (SpNQ-BR).

Thus, the Portuguese version of the SpNQ (SpNQ-BR) included 20 items and differentiated four factors. The first factor was composed of seven items, accounting for 18.5% of the explained variance and with an eigenvalue of 9.58. From its semantic content, it was named “Religious Needs”, and obtained loads between 0.52 and 0.83 factorials. The second factor was comprised of six items, explaining 14.9% of the variance, with an eigenvalue of 2.22 and factorial loads ranging from 0.51 to 0.69, and was called “Giving/Generativity Needs”. The third factor was labeled “Inner Peace”, and was composed of three items, explaining 11.6% of variance, with an eigenvalue of 1.74 and factorial loads ranging from 0.79 to 0.83. Finally, the fourth factor, named “Family Support Needs”, contained three items which were intended as additional ‘psychosocial’ items of the SpNQ, and explained 10.5% of the variance, showed a 1.48 eigenvalue and factorial loads between 0.64 and 0.72. The factorial structure obtained can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factorial structure, means, standard deviations, correlation items and factorial loads of the 20 Spiritual Needs Questionnaire Portuguese Version (SpNQ-BR) in a four-factors structure.

A solution of five factors (supposing Family Support Needs to be an additional dimension), Varimax rotation, and main axis extraction () was also considered. However, it was not observed to be statistically well grounded: Giving/Generativity Needs consisted, on this solution, of only two items, as can be seen in Table 3. Also on this statistical version many items (N27, N24, N02, N14, N15, N04, and N05) would have to be excluded making five factors version use inappropriate.

Table 3.

Factorial structure, means and standard deviations of the SpNQ—Portuguese Version in a structure of five factors.

4. Discussion

Spirituality is one of the aspects that differentiates human beings from other creatures, and a way to highlight differences among societies and individuals. In Brazil, we do not have data regarding PLHIV spiritual needs, as such, this is a pioneering study.

The SpNQ was originally written in German by (, ), and included 29 items that are not all used for the construct (19 items were used for the research instrument). In the Polish language () 20 items were tested and two items were deleted during the factorial analyses (item N4W and N6W). The Chinese version () was tested with 20 items, resulting in 17 items due to a weak factor loading of N2, N11, and N14. The Polynesian version () tested 19 items and for the Iranian and New Zealand English Languages translation there is no information about the tested items (); however, all these translations processes included the four-factor structure: Religious Needs, Existential Needs, Inner Peace Needs, and Giving/Generativity Needs. In the Croatian Language translation process () version 20 + 3 items was used to calculate the five factor scales, and, as an additional “non-spiritual” category, Social Support Needs (which is like our Family Support Needs scale). For the Persian version, the 19-item version was tested, and the five factors were tested and approved.

Nevertheless, there was stability of the four main factors with some variances, because some ‘existential’ items could be also be called ‘inner peace’ items, and vice versa. However, one has to take into account cultural and religious differences, because spirituality is a highly diverse set of beliefs, attitudes, and practices, and probably also needs. Moreover, the validation process of an interculturally-used instrument requires larger and more heterogeneous samples. This is also true for our sample of HIV positive patients, with 42% of them not stating their religious/spiritual orientation.

The diversity of translated versions caused a great deal of doubt in choosing the model to be tested in Brazil. Due to this, in the pilot test, we applied the SpNQ—27-item version to 26 in-patients with other diseases, using a five factor scale: Religious Needs, Existential Needs, Inner Peace Needs, Giving/Generativity Needs, and adding a category called Family Support Needs, which included questions regarding: Feeling connected with family, transmitting one’s own life experiences to others, being assured that your life was meaningful and of value, being rather involved by your family in their life concerns, and receiving more support from your family. These questions were present in former SpNQ versions. In that pilot test, Family Support Needs was the most important domain to the interviewed Brazilian patients ().

Family Support Needs was also found to be relevant in the Brazilian PLHIV sample, confirming the former pilot test results; this was different from other countries, where SpNQ was previously translated (; ; ; ), where these items were used only as ‘informative’ items because of their lack of a ‘spiritual’ connotation. Data about the spiritual needs of PLHIV in other countries were not found, making it impossible to compare data.

This fact, and the way in which spiritual needs are linked to religious needs in the researched Brazilian population, is probably linked to the cultural characteristics of the Brazilian people, who are markedly religious, so that it is reflected in their everyday lives, in the capacity of expression of multiple forms of religious faith. These cultural and religious beliefs account for a fundamental part of the ethos of Brazilian culture and are often confused with spirituality ().

These results reinforce the need to have a spiritual needs measure that, not only can be translated into several languages, but also fits the cultural characteristics of each country, allowing comparison of the obtained results. SpNQ has promising characteristics to be a measure that strengthens efforts that are being done to broaden the integration of spiritual care as an essential aspect of person-centered healthcare in many countries, as proposed by the Global Network for Spirituality and Health ().

The main limitation of this study is the rather small and young sample, as well as its exclusive focus on persons living with HIV. Therefore, further studies that enroll other persons from Brazil with chronic diseases are needed. With a more heterogeneous sample, the factorial structure may change slightly. The current validation process of the 20-item version (), enrolling healthy elderly and persons with chronic diseases showed that some items have a distinct relevance to persons with different life and health.

5. Conclusions

The translation of SpNQ showed that this measure had good internal validity and that its 20-item version can be used for research on the spiritual needs of Brazilian patients.

Cross-cultural adaptation and comparison with previous studies showed that the SpNQ can be adjusted to the cultural characteristics of different countries, especially regarding to the role and importance that societies give to religion and spirituality, remembering that the results of modifications to be proposed will certainly be influenced by the disease, the size of the sample to be researched and the study design.

We encourage subsequent studies regarding the theme in the largest Brazilian populations and in other Latin countries to confirm the results of this research.

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding are reported. We sincerely are grateful to Bussing who helped in the translation process and presented our work at the international meetings. We are very grateful to the undergraduate students, especially Anderson Tarocco Junior, that collaborated in the SpNQ translation and pilot test and Thiago Falheiros, undergraduate social sciences student that did the data collection

Author Contributions

Tania C. O. Valente and Ana Paula R. Cavalcanti conceived and designed the study. Rogerio N. Motta conducted data collection. Tania C. O. Valente, Ana Paula Cavalcanti, Clovis P. Costa Junior and Arndt Bussing analyzed the data. Tania C. O. Valente, Ana Paula R. Cavalcanti and Arndt Bussing wrote and revised the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Büssing, Arndt. 2015. Spirituality/Religiosity as a Resource for Coping in Soldiers: A Summary Report. Medical Acupuncture 27: 360–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Hans-Joachim Balzat, and Peter Heusser. 2009. Spirituelle Bedürfnisse von Patienten mit chronischen Schmerz- und Tumorerkrankungen. Perioperative Medizin 1: 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Hans-Joachim Balzat, and Peter Heusser. 2010. Spiritual needs of patients with chronic pain diseases and cancer—Validation of the spiritual needs questionnaire. European Journal of Medical Research 15: 266–73. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20696636 (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Büssing, Arndt, J. Janko, Andreas Kopf, Eberhard Lux, and Eckhard Frick. 2012. Zusammenhänge zwischen psychosozialen und spirituellen Bedürfnissen und Bewertung von Krankheit bei Patienten mit chronischen Erkrankungen. Spiritual Care 1: 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Xiao-Feng Zhai, Wen-Bo Peng, and Chang-Quan Ling. 2013. Validation of the Chinese Version of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire. Journal of Integrative Medicine 11: 106–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Klaus Baumann, Niels Christian Hvidt, Harold G. Koenig, Christina M. Puchalski, and John Swinton. 2014. Spirituality and Health. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014: 682817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Iwona Pilchowska, and Janusz Surzykiewicz. 2015. Spiritual Needs of Polish Patients with Chronic Diseases. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 1524–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Tânia Cristina de Oliveira Valente, Ana Paula Rodrigues Cavalcanti, Anderson Luís Carvalho Tarocco Jr., and Daniela Rodrigues Recchia. 2016. Brazilian Transcultural of Patient’s Spiritual Needs Questionnaire. Paper presented at 5th European Conference on Religion, Spirituality and Health and 4th International Conference of the British Association for the Study of Spirituality, Gdansk, Poland, May 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Daniela Rodrigues Recchia, Harold Koenig, Klaus Baumann, and Eckhard Frick. 2018. Factor Structure of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ) in Persons with Chronic Diseases, Elderly and Healthy Individuals. Religions 9: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Christopher Lance, Jeanne K. Kemppainen, William L. Holzemer, Lucille Sanzero Eller, Inge Corless, Nancy Reynolds, Kathleen M. Nokes, Pam Dole, Kenn Kirksey, Liz Seficik, and et al. 2006. Gender Differences in Use of Prayer as a Self-Care Strategy for Managing Symptoms in African Americans Living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 17: 16–23. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16849085 (accessed on 19 February 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Andrade, Maristela Oliveira. 2009. Brazilian Religiosity: Religious Pluralism, Diversity of Beliefs and the Syncretic Process. CAOS-Revista Eletrônica de Ciências Sociais 14: 106–18. Available online: http://www.cchla.ufpb.br/caos/n14/6A%20religiosidade%20brasileira.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Glavas, Andrijana, Karin Jors, Arndt Büssing, and Klaus Baumann. 2017. Spiritual Needs of PTSD Patients in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina: A Quantitative Pilot Study. Psychiatria Danubina 29: 282–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatamipour, Khadijeh, Maryam Rassouli, Farideh Yaghmaie, Kazem Zendedel, and Hamid Alavi Majd. 2018. Development and Psychometrics of a ‘Spiritual Assessment Scale of Patients with Cancer’: A Mixed Exploratory Study. International Journal of Cancer Management 11: e10083. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/ijcm.10083 (accessed on 25 January 2018). [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, Jeanne, Lucille Sanzero Eller, Eli Haugen Bunch, Mary J. Hamilton, Pamela J. Dole, William L. Holzemer, Kenn Kirksey, Patrice K. Nicholas, Inge Corless, Christopher Lance Coleman, and et al. 2006. Strategies for Self-Management of HIV-Related Anxiety. AIDS Care 18: 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2015. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: A Review and Update. Advances 29: 11–18. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26026153 (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Nejat, Nazi, Lisa Whitehead, and Marie Crowe. 2016. Exploratory Psychometric Properties of the Farsi and English Versions of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ). Religions 7: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraeni, Aan, Ikeu Nurhidayah, Nuroktavia Hidayati, Citra Windani Mambang Sari, and Ristina Mirwanti. 2015. Kebutuhan Spiritual pada Pasien Kanker. Jurnal Keperawatan Padjadjaran 3: 57–66. Available online: http://jkp.fkep.unpad.ac.id/index.php/jkp/article/view/101 (accessed on 2 February 2018). [CrossRef]

- Offenbaecher, M., N. Kohls, L. L. Toussant, C. Sigl, A. Winkelmann, R. Hieblinger, A. Whalter, and A. Büssing. 2013. Spiritual Needs in Patients Suffering from Fibromyalgia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013: 178547. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/178547 (accessed on 25 January 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, Christina M., Robert Vitillo, Sharon K. Hull, and Nancy Reller. 2014. Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: Reaching National and International Consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 642–65. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24842136 (accessed on 19 February 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, Christina M., Robert J. Vitillo, and Najmeh Jafari. 2016. Global Network for Spirituality and Health (GNSAH): Seeking More Compassionate Health Systems. Journal for the Study of Spirituality 1: 106–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Inez, Nancy L. McCain, and Ronald K. Elswick Jr. 2001. Spirituality and psychosocial factors in persons living with HIV. Journal of Advanced Nursing 33: 776–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, Tânia Cristina de Oliveira, Cavalcanti Ana Paula Rodrigues, Büssing Arndt, and Clóvis Pereira Costa Júnior. 2018. Transcultural adaptation and psychometric properties of Portuguese version of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire among people living with HIV in Brazil. Paper presented at 6th European Conference on Religion, Spirituality and Health and 5th International Conference of the British Association for the Study of Spirituality, Coventry, UK, May 17–19. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyngaard, Arnau. 2013. Addressing the Spiritual Needs of People Infected with and Affected by HIV and AIDS in Swaziland. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care 9: 226–40. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 1998. WHOQOL and Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs (SRPB)—Report on WHO Consultation. WHO/MSA/MHP/98.2, 2-23. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2014. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. Available online: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed on 19 February 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).