Ecclesial Opposition to Large-Scale Mining on Samar: Neoliberalism Meets the Church of the Poor in a Wounded Land

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Neoliberal Mining in the Philippines

2.1. Neoliberalism

2.2. Neoliberalism and Mining

2.3. Neoliberal Mining in the Philippines

3. The Church of the Poor

3.1. Historical Background

When the Roman Catholic Church opened the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, she was obliged to recognize and confront the rapid changes and the situation of humankind in the world. The church declared her gravest error to be the dichotomization between faith and practice; between professional and social activity, on the one hand, and the religious life on the other.

3.2. From Vatican II to PCP II: The Church of the Poor in the Philippines

Essentially the vision of the church in the Philippines in PCP II is to become a Church of the Poor- a church whose members are ‘in solidarity with the poor,’ and who ‘collaborate with the poor themselves and with others to uplift the poor from their poverty.’

3.3. Ecclesial Opposition to Mining in the Philippines

One social issue on which the Catholic Church has not remained silent in the face of what she perceives as injustices committed against the poor is that of mining. On this particular issue, the Philippine bishops have given credible witness to PCP II’s vision of a Church of the Poor. They have spoken out strongly against large-scale mining in a series of pastoral statements, marshaled the organizational resources and networks of the Church behind their advocacy, and shown remarkable solidarity with their poor and marginalized constituents.

To live, poor people eat and sell the fish they catch or the crops they grow-and typically those who manage to subsist in this way do so with very little margin. Natural resource degradation often becomes an immediate and life-and livelihood-threatening crisis- a question of survival.

| Environmental Effect | What This Entails |

|---|---|

| Hazardous Chemicals | Cyanide is frequently used as a processing agent in gold and silver mining and mercury is frequently produced as a by-product during mining. Spills of these chemicals can constitute a substantial threat to human health. |

| Water Contamination | Acid mine drainage can occur if the ore body contains iron and sulfur and if these minerals are exposed to water and oxygen. Acid mine drainage poses a serious threat to all aquatic biota and can lead to the mobilization of heavy metals such as arsenic, mercury, cadmium, and lead. |

| Air Pollution | Fugitive dust emissions from mining activities may cause serious respiratory problems in humans and lead to the asphyxia of plants and trees. |

| Deforestation | The removal of trees in open pit mining reduces habitat for endemic species and leads to more rapid runoff and flooding during the rainy season. |

| Water Siltation | Increased erosion leads to siltation of water systems and the degradation of fish habitat. |

| Water Depletion | Mining’s heavy use of water, in mineral processing and in pit dewatering, leads to a diminution of groundwater resources. |

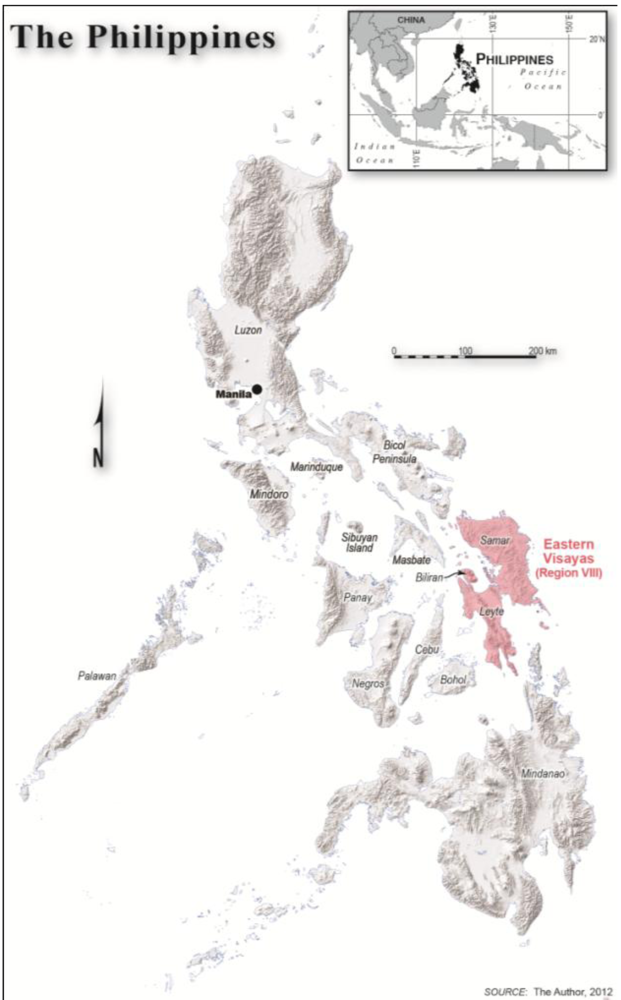

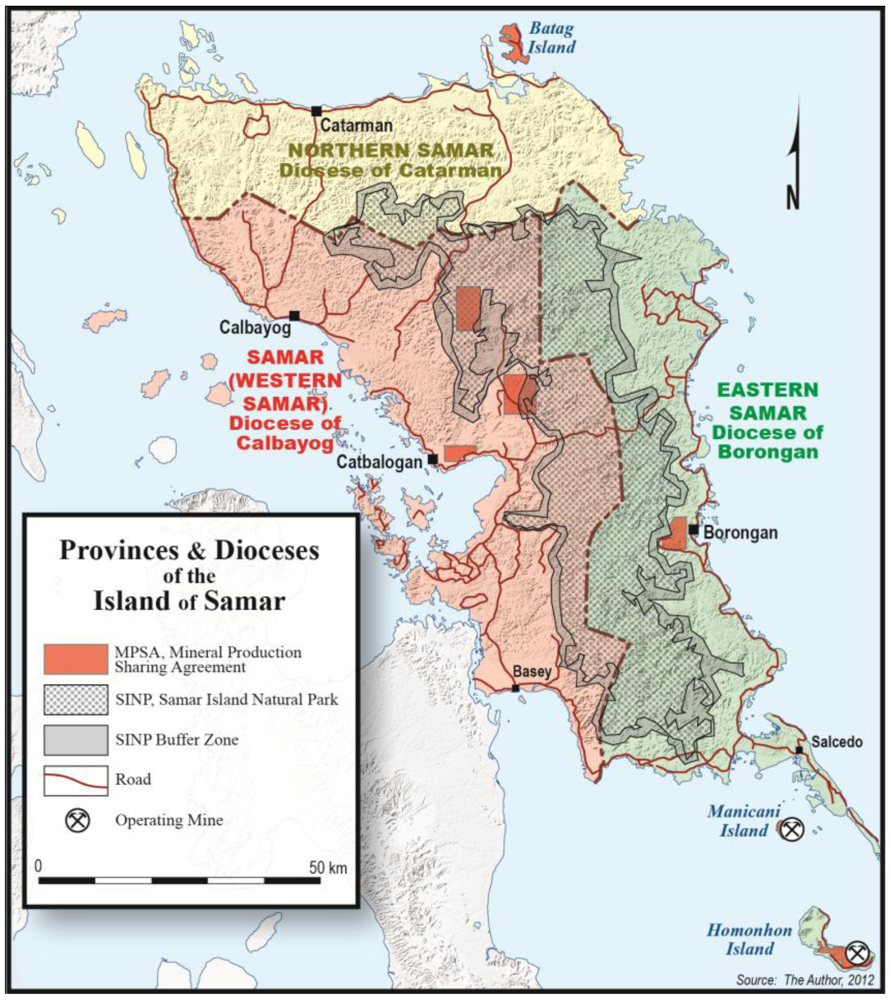

4. Samar: the Wounded Land

4.1. The Physical Geography of Samar

4.2. The Human Geography of Samar

Samar is without a doubt the poorest place we have seen in the Philippines. The people are deprived of the most elementary government services. The island has only a coastal road. The many barrios in the interior are not considered important enough for roads to be built. The traffic is carried out on the many waterways, which cut up the island, with small unmotorized prows, or on foot. The rivers are crossed by means of a simple bamboo bridge, with an improvised raft of banana stems or by wading through the stream. In the rainy season, many villages are cut off for months from the outside world.[60], p. 92

4.3. Samar: An Insurgency Hotbed

4.4. Human Rights Abuses in the Wounded Land

5. Ecclesial Opposition to Mining on Samar

5.1. Mining and Mineral Resources of Samar

5.2. Mining’s Impacts upon the Poor

| Date | Ecclesial Action Against Mining |

|---|---|

| 16 July 2003 | In response to information it had received regarding heavy siltation in the seas near Homonhon and Manicani islands the Diocese of Borongan asked the Secretary of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to conduct an investigation into the impact of mining operations on those islands [78]. |

| 8 August 2003 | A protest caravan, organized by all three dioceses, started from Catarman, Borongan, and Basey and ended in Catbalogan to protest the 5 December 2002 granting of Mineral Production Sharing Agreements for bauxite mining in the interior of Samar [78]. |

| 27 September 2003 | The Diocese of Calbayog, lauded Western Samar for passing a 50 year moratorium on large-scale mining. The Dioceses of Borongan and Catarman both urged their respective provinces to follow suit [78]. |

| 22 July 2004 | The Diocese of Borongan articulated its opposition to government efforts promoting mining and stating that it will not surrender its call for the preservation of the Samar Island Natural Park as well as an island wide ban on mining [78]. |

| 5 March 2006 | The Diocese of Borongan sent a letter to the DENR secretary asking for the cancellation of mining on Homonhon island. The letter stated that mining on Homonhon island has done harm to the environment and little to alleviate poverty [79]. |

| 10 March 2006 | Father Cesar Aculan, the Social Action Director of the Diocese of Calbayog, testified before a committee of the Philippine Senate and referred to the logging and mining industries as “twin industries of mass destruction” and called for a cleansing of the DENR of corrupt officials who act as fixers for those industries [80]. |

| 29 February 2008 | The three Samareño bishops, in conjunction with the bishops of Leyte, issued a pastoral letter warning that recent flooding in the Eastern Visayas is attributable to irresponsible mining. The bishops also stated that environmental abuse for money gives only minimal compensation and temporary employment to the poor [81]. |

| 22 October 2010 | The three Samarnon bishops, along with the other Eastern Visayan bishops, signed a pastoral letter warning that relying upon mining to act as a form of development will lead to a threatening of the ability of people to draw their life’s sustenance [82]. |

| 21 March 2011 | The Diocese of Borongan again called for an end to mining on Homonhon island [83]. |

| 2 February 2012 | The Diocese of Borongan appealed to President Benigno Aquino to impose a moratorium on mining in Eastern Samar to prevent further environmental degradation and to preserve farming and fishing [84]. |

| 19 March 2012 | All three Samareño dioceses, along with the other dioceses in the Eastern Visayas and a group of protestant churches, signed an ecumenical pledge to condemn and oppose large-scale mining [85]. |

| 15 May 2012 | All three Samarnon dioceses issued a joint pastoral letter expressing their outrage at the 1 May 2012 killing of Francisco Canayong, an anti-mining activist in Salcedo, Eastern Samar [86]. |

5.3. Mining and Samar’s Vulnerability to Natural Hazards

5.4. A Lack of Faith in Technology

5.5. The Threat Mining Poses to Samar’s Biodiversity

5.6. Mining and Militarization

The New People’s Army is under orders to dismantle large-scale mining projects and to attack and disarm the military, paramilitary, police and private security guarding these projects until they are forced to shut down.[97]

5.7. Mining and Human Rights Abuses

5.8. Mining is not Development

6. Discussion

6.1. The Effectiveness of Ecclesial Opposition

6.2. The Influence of the Church of the Poor

We are the heirs of earlier generations, and we reap benefits from the efforts of our contemporaries; we are under obligation to all men. Therefore we cannot disregard the welfare of those who will come after us to increase the human family. The reality of human solidarity brings us not only benefits but also obligations.[111], p. 5

Because the integrity of God’s creation is violated our people suffer the destruction brought about by droughts and floods. Those disasters cannot be traced merely to the uncontrollable powers of nature, but also to human greed for short term economic gain.

6.3. The Church of the Poor in Contradistinction to Neoliberalism

Clearly the neoliberals [were] not talking about workers in factories, nor women in families, nor peasants on plantations. They [meant], by the free individual, the entrepreneur, the capitalist, the boss. And they [meant], by freedom, the opportunity to make money.

6.4. The Church of the Poor as a Counter-Hegemonic Discourse

7. Conclusions

References and Notes

- A.F. Nicart. “Environmentalist Killed, 3 Samar Bishops Cry for Justice.” Philippine Information Agency, 17 May 2012. Available online: http://www.pia.gov.ph/news/index.php?article=1231336974282 (access on 10 June 2012).

- Dioceses of Borongan, Calbayog, and Catarman, A Prayer and Cry for Justice: Joint Pastoral Letter of Samar Island Catholic Bishops on the Brutal Murder of Francisco “Mano Francing” Canayong. Borongan: Diocese of Borongan, 2012.

- R.G. Mabunga. “Church witnessing: Values reflected in and the laity’s response to the pastoral letters of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines.” In Democracy and Citizenship in Filipino Political Culture. Edited by M.S.I. Diokino. Quezon City: The Third World Studies Center, 1997, Volume 1, pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- R.A.M. Santos, and B.O. Lagos. “The Untold People’s History: Samar Philippines.” Los Angeles: Sidelakes Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- K. Ward, and K. England. “Introduction: Reading Neoliberalization.” In Neoliberalization: States, Networks, Peoples. Edited by K Ward and K. England. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- D. Harvey. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- R. Blakeley. State Terrorism and Neoliberalism: The North in the South. London: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- J.A. Tyner. The Philippines: Mobilities, Identities, Globalization. London: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- R. Broad, and J. Cavanagh. Development Redefined: How the Market Met Its Match. London: Paradigm, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, H. Docena, M. de Guzman, and M.L. Malig. The Anti-Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines. Manila: Anvil Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 5.

- See ref. 8.

- A. Bebbington, I. Hinojosa, D.H. Bebbington, M. Burneo, and X. Warnaars. “Contention and Ambiguity: Mining and the Possibilities of Development.” Development and Change 39, 6 (2008): 887–914. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank, “Strategy for African Mining. World Bank Technical Paper Number 181 Africa Technical Department Series Mining Unit, Industry and Energy Division.” Washington: World Bank, 1992.

- Strongman, Strategies to Attract New Investment for African Mining. Washington: World Bank, 1994.

- R. Moody. Rocks and Hard Places: The Globalization of Mining. London: Zed Books, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- G. Bridge. “Acts of Enclosure: Claim Staking and Land Conversion in Guyana’s Gold Fields.” In Neoliberal Environments: False Promises and Unnatural Consequences. Edited by N. Heynen, J. Mccarthy, S. Prudham and P. Robbins. London: Routledge, 2007, pp. 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser Institute, Fraser Institute Annual Survey of Mining Companies 2011/2012. Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2012.

- N.G. Quimpo. “The Philippines: Predatory Regime, Growing Authoritarian Features.” The Pacific Review 22, 3 (2009): 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- See ref. 10.

- W.N. Holden, and R.D. Jacobson. Mining and Natural Hazard Vulnerability in the Philippines: Digging to Development or Digging to Disaster. London: Anthem Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- R.L. Neri. Importance of the Mining Sector to the Philippine Economy. Manila: National Economic Development Authority, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- L. Ilagan. “Legislative Actions on the Mining Issue in the Philippines.” In Mining and Women in Asia: Experiences of Women Protecting Their Communities and Human Rights against Corporate Mining. Edited by V. Yocogan-Diano. Chiang Mai: Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development, 2009, Volume 115-123. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 21.

- W.N. Holden, and R.D. Jacobson. “Ecclesial Opposition to Nonferrous Metals Mining in Guatemala and the Philippines: Neoliberalism Encounters the Church of the Poor.” In Engineering the Earth: The Impacts of MegaEngineering Projects. Edited by S. Brunn. Dordreccht: Kluwer, 2011, pp. 383–411. [Google Scholar]

- Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church. Vatican City: Libreia Editrice Vaticana, 2004.

- See ref. 3.

- M. Ramos-Llana. “The Church of the Poor in the Province of Albay: The Diocesan Social Action Center of Legazpi.” In Becoming a Church of the Poor: Philippine Catholicism after the Second Plenary Council. Edited by E.R. Dionisio. Quezon City: John J. Carroll Institute on Church and Social Issues, 2011, pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 25.

- R.O. Borrinaga. “Barangay Triana: The Right Site of the First Mass in Limasawa in 1521.” In Leyte-Samar Shadows: Essays on the History of Eastern Visayas. Edited by R.O. Borrinaga. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 2008, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- K.M. Nadeau. The History of the Philippines. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R. Constantino. The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Quezon City: Tala Publishing Service, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- E.A. Ordonez. “Recrudescence.” In Serve the People: Ang Kasaysayan ng Radikal na Kilusan sa Unibersidad ng Pilipinas. Edited by B. Lumbera, J. Taguiwalo, R. Tolentino, R. Guillermo and A. Alamon. Quezon City: IBON Books, 2008, pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- W.N. Holden, and K.M. Nadeau. “Philippine Liberation Theology and Social Development in Anthropological Perspective.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 38, 2 (2010): 89–129. [Google Scholar]

- T. Danenberg, C Ronquillo, J. de Mesa, E. Villegas, and M. Piers. Fired from within: Spirituality in the Social Movement. Manila: Institute of Spirituality in Asia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O.S. Suarez. Protestantism and Authoritarian Politics: The politics of Repression and the Future of Ecumenical Witness in the Philippines. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- G.R. Jones. Red Revolution: Inside the Philippine Guerrilla Movement. Boulder: Westview Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- E. Mendoza. Radical and Evangelical: Portrait of a Filipino Christian. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- R.L. Youngblood. “Marcos against the Church: Economic Development and Political Repression in the Philippines.” New York: CornellUniversity Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, Acts and Decrees of the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines. Pasay City: Pauline Publishing House, 1992.

- See ref. 28.

- A.M. Karaos. “The Church and the Environment: Prophets against the Mines.” In Becoming a Church of the Poor: Philippine Catholicism after the Second Plenary Council. Edited by E.R. Dionisio. Quezon City: John J. Carroll Institute on Church and Social Issues, 2011, pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 13.

- R. Broad. “The Poor and the Environment: Friends or Foes? ” World Development 22, 6 (1994): 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See ref. 42.

- F. Quimpo. “Current Trends in World Mining.” In Mining and Women in Asia: Experiences of Women Protecting Their Communities and Human Rights against Corporate Mining. Edited by V. Yocogan-Diano. Chiang Mai: Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development, 2009, pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 4.

- R.M. Rosales, and H.A. Francisco. “Estimating Non-Use Values of the Samar Island Forest Reserve.” Washington: United States Agency for International Development, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program, Samar Island Biodiversity Project: Final Report of the Terminal Evaluation Mission. New York: United Nations Development Program, 2006.

- See ref. 21.

- “National Statistics Office, Philippines in Figures, 2012.” Available online: http://www.census.gov.ph/data/census2010/index.html (accessed on 12 June 2012).

- S.C. Monsod, and T.C. Monsod. Philippines: Case Study on Human Development Progress Towards the MDG at the Sun-National Level, Human Development Report Office Occasional Paper, Background Paper for HDR 2003. New York: United Nations Development Program, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 49.

- C. Varquez. “Bishop, Diocese of Borongan.” Personal Interview, Borongan: Borongan, Eastern Samar, 4 June 2012.

- See ref. 4.

- See ref. 49.

- National Statistical Coordination Board, Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines. Quezon City: National Statistical Coordination Board, 2005.

- See ref. 4.

- C. Aculan. “Father, Social Action Director, Diocese of Calbayog.” Personal Interview, Catbalogan, Samar, Philippines, 6 June 2012.

- B. De Belder, and R. Vanobberghen. Kasama: The Philippine Struggle for Health Care and Liberation through the Eyes of Two Belgian Doctors. Brussels: Anti-Imperialist League, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 4.

- C. Conde. “Journalist, International Herald Tribune.” Personal Interview, Quezon City, 12 November 2009.

- International Crisis Group, The Communist Insurgency in the Philippines: Tactics and Talks. Asia Report No. 202; Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2011.

- R. Rutten. “Introduction: Cadres in Action, Cadres in Context.” In Brokering a Revolution: Cadres in a Philippine Insurgency. Edited by R. Rutten. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila Press, 2008, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 52.

- See ref. 4.

- Samar Island Biodiversity Project, Samar Island Natural Park Management Manual. Quezon City: Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 2006.

- W.N. Holden. “A Neoliberal Landscape of Terror: Extrajudicial Killings in the Philippines.” Acme 11, 1 (2012): 145–176. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch, The Philippines: Scared Silent: Impunity for Extrajudicial Killings in the Philippines. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2007.

- Karapatan, Karapatan 2011 Report on the Human Rights Situation in the Philippines. Quezon City: Karapatan, 2011.

- A.A. Parreno. Report on the Philippine Extrajudicial Killings (2001–August 2010). San Francisco: The Asia Foundation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- A.A. Parreno. “Human Rights Activist.” Personal Interview, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 2012.

- See ref. 49.

- “Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Mines and Geosciences Bureau, Mining Tenements Management Division, Complete List of Existing Mineral Production Sharing Agreements, as of 30 June 2012.” Available online: http://www.mgb.gov.ph/Files/Permits/Applications/May_2011_MPSA_2A.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2012).

- “Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Mines and Geosciences Bureau, RD De Dios Extends IEC to SIPPAD, Warns of Social Repercussions on Mining Moratorium.” 2012. Available online: http://web.evis.net.ph/lineagencies/mgb/mgb_drupal/mgb/?q=content/rd-de-dios-extends-iec-sippad-warns-social-repercussions-mining-moratorium (accessed on 5 July 2012).

- V.C. Abueme. “President, Homonhon Environment Resources Organization.” Personal Interview, Borongan, Eastern Samar, Philippines, 4 June 2012.

- N. Baddilla. “Coordinator, Save Manicani Movement, Borongan.” Personal Interview, Eastern Samar, Philippines, 5 June 2012.

- Justice Peace Integrity of Creation Commission-Association of Major Religious Superiors of the Philippines, The Church’s Perspective on Mining in the Philippines. Quezon City: Justice Peace Integrity of Creation Commission-Association of Major Religious Superiors of the Philippines, 2007.

- J.A. Gabieta. “Samar Clergy Want Chromite Mining Permit Cancelled.” Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2006. Available online: http://news.inq7.net/regions/index.php?index=1&story_id=68350.

- See ref. 78.

- C.G. Cabuenas. “Samar, Leyte Bishops Appeal for Environment Protection.” Philippine Daily Inquirer. 29 February 2008. Available online: http://www.inquirer.net/specialreports/theenvironmentreport/view.php?db=1&article=20080229-121978.

- GMA News. “6 Bishops Appeal to Government: Stop Mining in Eastern Visayas.” GMA News. 31 October 2010. Available online: http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/204773/news/regions/6-bishops-appeal-to-govt-stop-mining-in-eastern-visayas.

- N.I. Quirante. “Bishop backs anti-mining group in Homonhon.” Philippine Information Agency. 2011. Available online: http://www.pia.gov.ph/?m=1&t=1&id=23491.

- CBCP News. “Samar Bishops Outraged Over Killing of Anti-Mining Advocate.” CBCP News. 2012. Available online: http://www.cbcpnews.com/?q=node/19480.

- Samar News. “An ecumenical pledge to condemn and oppose large-scale mining in Eastern Visayas, Masbate province and all over the country.” Samar News. 19 March 2012. Available online: http://www.samarnews.com/news2012/mar/b691.htm.

- 86. See ref. 2.

- See ref. 21.

- J. Calumpiano. “Father. Chairman, Diocesan Commission on Social Action, Justice, and Peace, Diocese of Borongan.” Personal Interview, Diocese of Borongan, Borongan, Eastern Samar, Philippines, 4 June 2012.

- A. Galo. “Father. Member, Diocesan Commission on Social Action, Justice, and Peace, Diocese of Borongan.” Personal Interview, Diocese of Borongan, Borongan, Eastern Samar, Philippines, 4 June 2012.

- See ref. 21.

- W.N. Holden. “A Lack of Faith in Technology? Civil Society Opposition to Large-Scale Mining in the Philippines.” The International Journal of Science in Society 2, 2 (2011): 274–299. [Google Scholar]

- J. Emel, and R. Krueger. “Spoken but not Heard: The Promise of the Precautionary Principle for Natural Resource Development.” Local Environment 8, 1 (2003): 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See ref. 13.

- See ref. 49.

- See ref. 67.

- See ref. 21.

- National Democratic Front of the Philippines, Eastern Visayas. “NDF-EV is in solidarity with the stand of church leaders in the region against large-scale mining.” 3 April 2012. Available online: http://www.samarnews.com/news2012/apr/b734.htm.

- M. Patalinghug-Vasquez. “Central and Eastern Visayas Coordinator, Task Force Detainees of the Philippines.” Personal Interview, Cebu City, Philippines, 12 June 2005.

- “Citizens’ Council for Human Rights. “Documented Cases of Human Rights Violations.” January 2004 to June 2006.” Available online: http://www.pinoyhr.net/reports/CCHRcases.pdf.

- See ref. 21.

- See ref. 4.

- R.E. Ofreneo. “Failure to Launch: Industrialization in Metal-Rich Philippines.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 14, 2 (2009): 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.M. Nadeau. “Christians against Globalization in the Philippines.” Urban Anthropology 34, 4 (2005): 317–339. [Google Scholar]

- C. Avila. “The Philippine Church on Mining Issues.” Impact: Asian Magazine for Human Transformation 42, 3 (2008): 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser Institute, Fraser Institute Annual Survey of Mining Companies 2010/2011. Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2011.

- See ref. 21.

- See ref. 42.

- See ref. 49.

- See ref. 67.

- World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- VI. Paul. “Populorum Progressio. Encyclical of Pope Paul VI on the Development of Peoples.” Vatican City: Vatican, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- J.L. Kater. “Whatever Happened to Liberation Theology? New Directions for Theological Reflection in Latin America.” Anglican Theological Review 30, 4 (2001): 735–773. [Google Scholar]

- D. Tombs. “Latin American Liberation Theology Faces the Future.” In Faith in the Millennium. Edited by S.E. Porter, M.A. Haynes and D. Tombs. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001, pp. 32–58. [Google Scholar]

- S. Baltodano. “Pastoral Care in Latin America.” American Journal of Pastoral Counseling 5, 3 (2002): 191–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Brackley, and T.L. Schubeck. “Moral Theology in Latin America.” Theological Studies 63 (2002): 123–160. [Google Scholar]

- G. Gutiérrez. A Theology of Liberation, 15th Anniversary ed. New York: Orbis Books, Maryknoll, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 42.

- See ref. 40.

- See ref. 21.

- D. Harvey. “Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction.” Geografiska Annaler B 88, 2 (2006): 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, Letter to President Benigno Aquino, Manila: Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, 2010.

- See ref. 35.

- R. Peet, and E. Hartwick. Theories of Development: Contentions, Arguments, Alternatives. New York: Guildford Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- R. Peet. Unholy Trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO. London: Zed Books, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 9.

- M. Watts. “What might resistance to neoliberalism consist of? ” In Neoliberal Environments: False Promises and Unnatural Consequences. Edited by N. Heynen, J. Mccarthy, S. Prudham and P. Robbins. London: Routledge, 2007, pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- See ref. 124.

- H. Moksnes. “Suffering for Justice in Chiapas: Religion and the Globalization of Ethnic Identity.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 32, 2 (2005): 584–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See ref. 115.

- See ref. 4.

- See ref. 25.

- L. Boff. Global Civilization: Challenges to Society and Christianity. London: Equinox, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- P. Berryman. “Church and revolution: Reflections on Liberation Theology.” NACLA Report on the Americas 30, 5 (1997): 10–15. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Holden, W.N. Ecclesial Opposition to Large-Scale Mining on Samar: Neoliberalism Meets the Church of the Poor in a Wounded Land. Religions 2012, 3, 833-861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3030833

Holden WN. Ecclesial Opposition to Large-Scale Mining on Samar: Neoliberalism Meets the Church of the Poor in a Wounded Land. Religions. 2012; 3(3):833-861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3030833

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolden, William Norman. 2012. "Ecclesial Opposition to Large-Scale Mining on Samar: Neoliberalism Meets the Church of the Poor in a Wounded Land" Religions 3, no. 3: 833-861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3030833

APA StyleHolden, W. N. (2012). Ecclesial Opposition to Large-Scale Mining on Samar: Neoliberalism Meets the Church of the Poor in a Wounded Land. Religions, 3(3), 833-861. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3030833