Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Mental Health Care, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy

Abstract

: Integrating spirituality into mental health care, psychiatry and psychotherapy is still controversial, albeit a growing body of evidence is showing beneficial effects and a real need for such integration. In this review, past and recent research as well as evidence from the integrative concept of a Swiss clinic is summarized.Religious coping is highly prevalent among patients with psychiatric disorders. Surveys indicate that 70–80% use religious or spiritual beliefs and activities to cope with daily difficulties and frustrations. Religion may help patients to enhance emotional adjustment and to maintain hope, purpose and meaning. Patients emphasize that serving a purpose beyond one's self can make it possible to live with what might otherwise be unbearable.Programs successfully incorporating spirituality into clinical practice are described and discussed. Studies indicate that the outcome of psychotherapy in religious patients can be enhanced by integrating religious elements into the therapy protocol and that this can be successfully done by religious and non-religious therapists alike.1. Spirituality in Mental Illness and Psychiatric Disorders

Spiritual approaches to mental illness are still at their infancy, certainly in Europe. There is an ongoing controversy on whether or not to integrate spirituality into the treatment of persons suffering from mental illness, mainly due to concerns about harmful side effects from encouraging and supporting religious involvement. On the other hand, a growing body of evidence is showing beneficial outcomes of religious and spiritual approaches to psychiatric disorders. Spirituality can be seen as a unique human dimension [1], making life sacred and meaningful [2], being an essential part of the physician-patient-relationship [3] and the recovery process [4,5].

Persons suffering from mental illness emphasize that understanding one's problems in religious or spiritual terms can be a powerful alternative to a biological or psychological framework. Although reframing the issue in this manner may not change reality, having a higher purpose may make a big difference in an individual's willingness to bear pain, to cope with difficulties, and to make sacrifices. Given the fact that people with serious mental illnesses already struggle against widespread prejudice and discrimination, it would seem important to maintain or strengthen people's existing religious affiliations and support systems as part of their treatment or rehabilitation plan [2].

Lindgren and Coursey [6] interviewed participants in a psychosocial rehabilitation program: 80% said that religion and spirituality had been helpful to them. Trepper et al. [7] found that participants experiencing greater symptom severity and lower overall functioning are more likely to use religious activities as part of their coping. Symptom-related stress leads to greater use of religious coping, a phenomenon that has also been shown in other studies [8,9]. Baetz et al. [10] demonstrated among psychiatric inpatients that both public religion (e.g., worship attendance) and private spirituality were associated with less severe depressive symptoms. Religious patients also had shorter lengths of stay in the hospital and higher life satisfaction.

Koenig, George, and Peterson [11] followed medically ill elderly persons who were diagnosed with a depressive disorder and found that intrinsic religiosity (following religion as an “end in itself,” rather than as a means to another end) was predictive of shorter time to remission of depressive disorder, after controlling for multiple other predictors of remission. Pargament [12,13] has extensively studied the role of religious coping methods in dealing with stress. He found consistent connections between positive styles of religious coping and better mental health outcomes. Religious coping styles such as perceived collaboration with God, seeking spiritual support from God or religious communities, and benevolent religious appraisal of negative situations have been related to less depression [11], less anxiety [14] and more positive affect [15].

2. A Holistic and Integrative Framework for Therapy

2.1. The Extended Bio-Psycho-Social Model

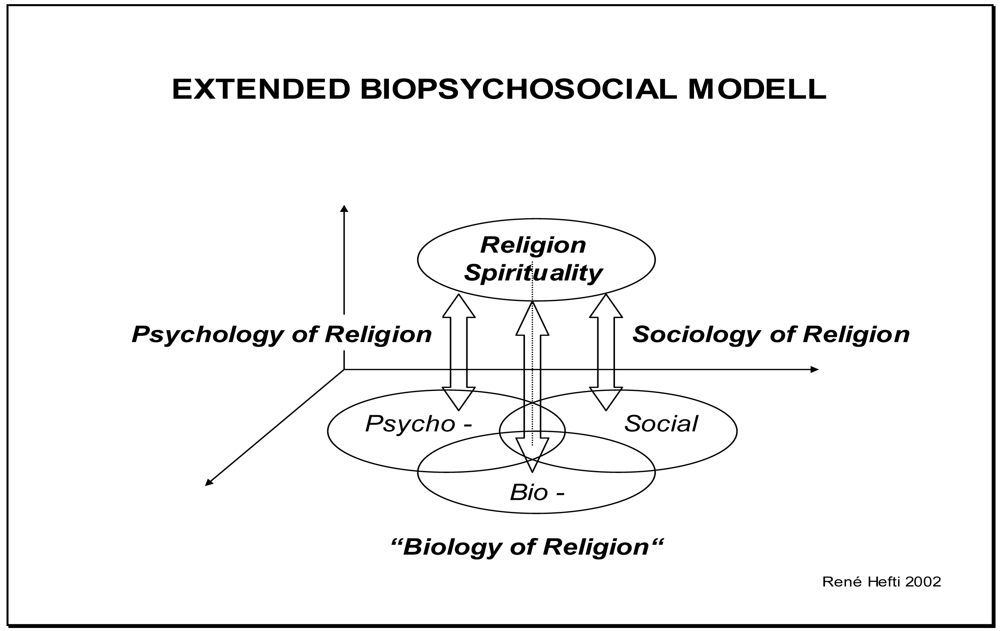

In psychiatry and psychosomatic medicine, the bio-psycho-social model introduced by George L. Engel in 1977 [16], is the predominant concept in clinical practice and research. It shows that biological, psychological and social factors interact in a complex manner in health and disease. In the extended bio-psycho-social model [17], religion and spirituality constitute a fourth dimension (Figure 1). This holistic and integrative framework is a useful tool to understand how religion and spirituality influence mental as well as physical health. Interactions with the biological, psychological and social dimension constitute the distinct disciplines of “biology of religion”, psychology of religion and sociology of religion. The extended bio-psycho-social model illustrates that a holistic approach in mental health has to integrate pharmacotherapeutic, psychotherapeutic, sociotherapeutic and spiritual elements.

2.2. Religion and Spirituality as Resource or Burden

Religion and spirituality can have beneficial or adverse effects on health. In general, people who are more religious report better physical health, psychological adjustment, and lower rates of problematic social behavior [18-21]. Spirituality strengthens a sense of self and self-esteem [22,23], of feeling more like a “whole person” and of being valued by the divine (as part of creation, as a “child of God”), countering stigma and shame with positive self-attributions and, by all of this, reinforcing “personhood” [24].

Spirituality is associated with decreased levels of depression [25], especially among people with intrinsic religious orientation based on internalized beliefs [26]. Spirituality correlates with lower levels of general anxiety [27] and with positive outcomes in coping with anxiety [28]. Higher levels of spirituality among individuals recovering from substance abuse are related to optimism and resiliency against stress [29], and spiritual coping methods are found to have positive effects for persons diagnosed with schizophrenia [30]. Participation in spiritual and religious activities helps to integrate individuals into their families [31].

Religion and spirituality also deliver social and community resources [22,23] which are enhanced by the “transcendent nature” of the support. Belonging to and finding acceptance in a religious community may have special importance for people who are often rejected, isolated, or stigmatized [32]. Spiritual experiences facilitate the development of a fundamental sense of connectedness. Religion and spirituality also foster a sense of hope and purpose, a reason for being, as well as opportunities for growth and positive change [5,23,33]. These are ways in which patients have expressed their experience of enhanced personhood or empowerment.

Aside from the beneficial effects, it is important to be aware of the “negative” influence religion and spirituality can have on mental health outcomes and recovery. Negative religious coping involves beliefs and activities such as expressing anger at God, questioning God's power, attributing negative events to God's punishment, as well as discontent with religious communities and their leadership. Negative religious coping has been linked to greater affective distress, including greater anxiety, depression and lower self-esteem [34]. Religious struggles involving interpersonal strain rather than social support and conflicts with God rather than perceived collaboration have been linked to higher levels of depression and suicidality [35]. Negative experiences with religious groups can aggravate feelings of rejection and marginalization [36].

Unfavorable religious convictions can intensify excesses of self-blame and perceptions of unredeemable sinfulness. If they are woven into obsessive or depressive symptom patterns, they can be even more distressing. Furthermore, emotional struggles and feelings of rejection can be reinforced by religious communities who see mental disorders as signs of moral or spiritual weakness or failure. Prayer or other religious rituals can become compulsive and interfere with overall daily functioning [7]. Finally, beliefs involving themes of divine abandonment or condemnation, unrelenting rejection, or powerful retribution may make recovery seem unattainable or unimportant [37].

3. The Key Roles of Religious and Spiritual Coping

3.1. Findings from the Literature

Several surveys showed a high prevalence of religious coping among patients with severe and persistent mental illness. Tepper et al. [7] investigated 406 patients at one of thirteen Los Angeles County mental health facilities. More than 80 percent of the participants used religious beliefs or activities to cope with daily difficulties or frustrations. A majority of participants devoted as much as half of their total coping time to religious practices, with prayer being the most frequent activity. Specific religious coping strategies, such as prayer or reading the Bible, were associated with higher SCL-90 scores (indicating more severe symptoms), more reported frustration, and a lower GAF score (indicating greater impairment). The amount of time that participants devoted to religious coping was negatively related to reported levels of frustration and scores on the SCL-90 symptom subscales. The results of the study suggest that religious activities and beliefs may be particularly important for persons who are experiencing more severe symptoms, and increased religious activity may be associated with reduced symptoms over time.

This is not only true in the United States but also in Europe. The findings of Tepper et al. have been replicated by Mohr et al. in Geneva, Switzerland [38]. Semi-structured interviews focused on religious coping were conducted with a sample of 115 outpatients with psychotic illness at one of Geneva's four psychiatric outpatient facilities. For a majority of patients, religion instilled hope, purpose, and meaning in their lives (71%), whereas for some, it induced spiritual despair (14%). Patients also reported that religion lessened (54%) or increased (10%) psychotic and general symptoms. Religion was found to increase social integration (28%), although on occasion led to social isolation (3%). It reduced (33%) or increased (10%) the risk of suicide attempts, reduced (14%) or increased (3%) substance use, and fostered adherence to (16%) or was in opposition to (15%) psychiatric treatment. The results highlight the clinical significance of religion and religious coping for patients with schizophrenia, encouraging integration of spirituality into the psychosocial dimension of care.

Huguelet et al. from the same public psychiatric outpatient department in Geneva investigate spirituality and religious practices of outpatients (N = 100) with schizophrenia and compared them with their clinician's knowledge of patients' religious involvement [39]. Audio-taped interviews were conducted about spirituality and religious coping. The patients' clinicians (N = 34) were asked about their own beliefs and religious activities as well as their patients' religious and clinical characteristics. A majority of the patients reported that religion was an important aspect of their lives, but only 36 percent of them had raised this issue with their clinicians. Fewer clinicians were religiously involved, and, in half the cases, their perceptions of patients' religious involvement were inaccurate. Some patients considered treatment to be incompatible with their religious practice, but clinicians were seldom aware of such conflicts.

3.2. Clinical Experience and Qualitative Research

The findings about religious coping reflect the experiences made at a clinic for psychosomatics, psychiatry and psychotherapy in Langenthal, Switzerland ( www.klinik-sgm.ch). For a majority of the patients, religious or spiritual coping is an essential part of their coping behavior. Religion provides patients with a framework to cope with disease-related struggles. Existential needs such as being secure, valued and having meaning [40] are addressed by clinicians and pastoral counselors—despite and beyond psychiatric conditions. Two examples of open, unstructured interviews performed with depressed patients at the clinic as part of a qualitative study [41] illustrate this:

First example

A 32-year-old male patient is married and has a one-year-old son. He has been working in the same company for many years and is a member of a Protestant Church. He was hospitalized because of a severe depressive episode. How did he use religious coping to overcome his depression?

By reading scriptures/psalms: “Reading psalms helped me a lot to feel closer to God in difficult times. I realized that others (the writers of the psalms) also had to cry and felt desperate in their situation. They argued with God and pleaded to him.”

By getting spiritual support: “In the very dark moments, when I felt totally lost and abandoned by God, I couldn't cope with my situation anymore. I couldn't fight negative thoughts about the future and myself. I needed somebody from outside to tell me that these are lies, that I am not abandoned either by God or by my family, that I am not worthless but loved.”

Second example

A 65-year-old female patient grew up in a small country village. She had five brothers and sisters. Her father was an alcoholic. The patient left home at an early age. Her first marriage collapsed because of her husband's alcoholism. They had two children. After the divorce, the patient experienced her first depression. Later, she married again and became a member of a Methodist Church (after a religious conversion). Depressive episodes became less frequent and less severe. What helped the patient to cope better with depression?

Controlling depression by faith/prayer: “When I feel sad and my thoughts become gloomy, when I wake up early in the morning and can't sleep anymore, then I go outside into nature and speak with God, thanking him for being in control and for not letting me go down.”

Not asking why: “In past times I always began to ask why, why did I marry this man, why did God let this happen? But this made things worse. Today I stop this kind of thinking and focus on God.”

4. Mental Health Care Programs Integrating Religion and Spirituality

In the following paragraphs, four mental health care programs integrating religion and spirituality into a mental health care setting are summarized. A more detailed description of these programs can be found elsewhere [42].

4.1. Therapy Group on Spiritual Issues at Cambridge Health Alliance Belmont

The first therapy group on spiritual issues was started by Nancy Kehoe in 1981 in the department of psychiatry at Cambridge Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School, Belmont, Massachusetts [43]. She felt the need to provide seriously mentally ill persons with an opportunity to explore religious and spiritual issues in relation to their mental illness. At first, the idea of having such a group generated anxiety, fear, and doubt among staff members. It brought out the ambivalence that many mental health professionals have about religious issues, an ambivalence reflected in Gallup poll findings [44]. In addition, Bergin and Jensen's work [45] has highlighted the marked difference between the religious beliefs and practices of the general population and those of the mental health professionals. Staff training and instruction alleviated some staff concerns about Kehoe's group. However, the long-term success of the group has been the strongest factor in staff acceptance. Group rules contributing to its success are tolerance of diversity, respect of others' beliefs, and a ban on proselytizing. Another factor is that membership is open to all, regardless of religious background or diagnosis.

4.2. Spirituality Group at the Hollywood Mental Health Center Los Angeles

In a standard psychosocial rehabilitation program emphasizing skills training, psycho-education, and cognitive behavioral treatment [46], a spirituality group was offered as a 60-minute optional weekly session [47] in the same time slot as the regular standard group. Each session focused on a topic of interest (e.g., forgiveness). Spiritual interventions included discussing spiritual concepts (e.g., helping participants to see their self-worth based in God's promises), encouraging forgiveness, referring to spiritual writings (e.g., the story of the prodigal son, Luke 15, 11–32), listening to spiritual music, and encouraging spiritual and emotional support among the group members (e.g., praying for one another).

The general purposes of the interventions were to help participants understand their problems from an eternal, spiritual perspective, to gain a greater sense of hope, to emotionally forgive and heal past pain, to accept responsibility for their own actions, and to experience and affirm their sense of identity and self-worth. Participants were also encouraged to connect with their faith communities.

All 20 participants (100%) in the spirituality group achieved their treatment goals, compared to 16 out of 28 people (57%) in the non-spirituality group. The difference in goal attainment between the two groups was highly significant (p = 0.0001). One participant with a 30-year history of agoraphobia and daily panic attacks shared that she was able to “push away” the symptoms by utilizing a combination of prayer and relaxation techniques. Participants as a group stated that sensing God's presence helped to lessen feelings of sadness, calm fears and anxieties, deal with forgiveness and resolve daily problems. The findings from the Wong study suggest that inclusion of spirituality in psychiatric rehabilitation is a promising approach.

4.3. Spirituality Matters Group at the Nathan Kline Institute New York

The Spirituality Matters Group (SMG) was developed in 2001 at the Clinical Research Evaluation Facility of the Nathan Kline Institute for hospitalized persons with persistent psychiatric disabilities [48], following the rationale that spiritual support fosters the recovery process. SMG is distinct from comparable groups in its multidisciplinary leadership that focuses on integrating spiritual/religious, psychological and rehabilitative perspectives. The SMG is made up of self-referred persons who join three group co-leaders (representing psychology, pastoral care and rehabilitation) in exploring non-denominational religious and spiritual themes designed to facilitate comfort and hope, while addressing prominent therapeutic concerns. Patients are told this group “focuses on the use of spiritual beliefs for coping with one's illness and hospitalization”. The highly-structured group format accommodates cognitive deficits and limited social skills that are prevalent in persons with persistent psychiatric disabilities.

During each session's initial phase, new members are introduced, the group's purpose reviewed, the multi-religious and non-denominational nature of the group affirmed, and spirituality defined as “personal beliefs and values related to the meaning and purpose of life, which may include faith in a higher purpose or power.” In the middle phase, a topic with a related group activity is presented. Topics are selected by leaders on a rotating basis and carefully prepared so that both negative and positive emotions are addressed. Group members are encouraged to share how the topic has relevance to the perception of their illness, previous behavior patterns, treatment failures, and future goals. In the ending phase, group members summarize the session's emergent themes and new learning's.

Group activities are: 1. Readings from the Book of Psalms [49]. Psalms evoke the full range of human emotions from thanksgiving and praise to anger, fear, desperation, despair, abandonment, hope and protection. Reading selected Psalms emphasizes the universal nature of experiencing conflicts and struggles in daily life, while focusing on elements of faith that maintain strength and perseverance during these difficulties. 2. Reciting prayers together that are familiar and common reinforce individuals' existing religious and spiritual practices. 3. Writing prayers helps improve self-awareness of one's needs and allows articulation of one's experiences in a setting that brings comfort and a sense of closure. 4. Reading spiritual stories allows group members to identify personal values.

Most of these group activities can be understood as emotion-focused coping [50]. It includes cognitive reframing, social comparisons, minimization (“looking on the bright side of things”), and behavioral efforts to feel better (exercise, relaxation, meditation). Emotion-focused coping is useful when a situation cannot be changed, but only the emotional response can be changed, which is self-affirming and empowering. This coping style can co-exist with problem-focused approaches.

4.4. Spiritual Issues Psychoeducational Group at Bowling Green State University

The program was a seven-week semi-structured, psycho-educational intervention at the Psychology Department of Bowling Green State University Ohio [51]. Two doctoral students in clinical psychology served as ongoing facilitators for each group session (1.5 hours). Participants discussed religious resources, spiritual struggles, forgiveness, and hope. The intervention was designed to provide new information about spirituality to participants and to allow them to share experiences and knowledge. An additional goal was to present a more inclusive set of spiritual topics to clients with severe mental illness (Table 1).

Group members were recruited through referrals from mental health workers at a local community mental health center. Potential members participated in individual interviews to determine whether their needs, expectations and level of functioning were appropriate for the group. One third of the group members reported a diagnosis of schizophrenia, one third indicated a diagnosis of depression, and one-third reported personality disorders as their primary diagnosis. In terms of religious affiliation, thirty percent identified themselves as Roman Catholic while all others were affiliated with Protestant denominations. Seventy percent indicated that they attend church on a weekly basis.

In conclusion, this intervention provided a safe environment for those with severe mental illness to discuss spiritual concerns. This unique intervention appeared to be highly valued by participants. Community mental health professionals may feel that it is not their place to employ a spiritual issues group in a publicly funded agency. Yet Richards and Bergin [55] note that there “are no professional ethical guidelines that prohibit therapists in civic settings from discussing religious issues or using spiritual interventions with clients.” In fact, they assert, it is unethical to derogate or overlook this dimension. With some training in the area of serious mental illness and spiritual concerns, professionals from diverse areas of training could lead such “spirituality groups”.

5. Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Psychotherapy

5.1. The Holistic Concept of a Swiss Clinic

The Clinic SGM Langenthal for psychosomatics, psychiatry and psychotherapy has integrated religion and spirituality into the therapeutic concept from the beginning. The theoretical framework for this integration is the extended bio-psycho-social model [17] as described earlier in this article. In mental as well as in physical illness, there is always an existential and therefore spiritual dimension which should be explored, because it will influence therapy in an explicit or implicit way. For this reason, a short spiritual history is taken from every patient to assess the relevance of spirituality in the patient's life and illness. A special emphasis lies on identifying spiritual resources and burdens. If religion or spirituality is relevant for a patient, it is important to understand how he/she wants to implement this dimension into therapy and what the therapist's role should be.

A patient can, as an example, integrate spiritual goals into his/her treatment plan: e.g. regaining hope and meaning; strengthening the relationship with God to better cope with mental illness; persevering in difficult psychosocial circumstances; resolving anger, frustration or disappointment towards God; understanding why God allows bad things to happen in a patient's life, working towards forgiveness in broken relationships; and being more aware of God's presence and guidance in daily life. Spiritual goals are discussed in the interdisciplinary team, of which the pastoral counselor is a full member. It is important that spiritual goals are in line (do not conflict) with other treatment goals. “Spirituality” can be used (or misused) to escape from difficult circumstances. This would not be supported in the therapeutic context.

For many years, the clinic offers psycho-educational group meetings focusing on the integration of therapeutic and spiritual aspects, and emphasizing the benefit and importance of religious and spiritual coping [7,12,38,51]. Topics of these psycho-educational group meetings are: Developing a positive perspective for life despite illness and limitations, coping with fear and depression, listening to the Book of Psalms, developing a spiritual identity (“I called you by your name”), fostering personhood, and reflecting on healthy and unhealthy religious and spiritual beliefs.

The integration of spiritual issues into psychotherapy [24] represents a further aspect of the clinic's holistic concept. A patient in a psychotic state felt energized by God's overwhelming presence in his mind and body. The therapist challenged this “spiritual perception” during the psychotherapeutic consultation, and asked for other possible explanations. If a patient has unhealthy beliefs, it is important to challenge them from a spiritual as well as a psychotherapeutic point of view. Further topics are feelings of guilt, being rejected or abandoned by the divine, working towards forgiveness.

5.2. The Impact of Religiosity on the Outcome of Psychotherapy in a Inpatient Sample

To evaluate the impact of religiosity on the outcome of psychotherapy, a longitudinal study with a pre-post-design has been conducted at the clinic in Langenthal, Switzerland [56]. The rationale behind this investigation was that religiosity can be conceptualized as a personal resource for religiously oriented patients [57], and that the activation of this resource may support therapeutic processes [58] and improve health outcomes. In the newer literature on empirically validated mechanisms of change in psychotherapy, personal resources seem to play an important role. According to Klaus Grawe,“resource activation” is a key mechanism of change [59] and also an important factor for the improvement of subjective well-being [60]. In psychosomatic and psychiatric patients' religious behaviour, experience and thinking may be particularly important for well-being. According to Howard et al. [61], the improvement of subjectively experienced well-being is associated with reduction in symptomatic distress, and the latter is associated with changes of life functioning.

The sample consisted of 189 inpatients from the clinic for psychosomatics, psychiatry and psychotherapy in Langenthal. Data was collected as a standard quality management procedure. The mean age was 43 years. More than two thirds of the patients were female. The mean duration of treatment was 70 days. There were some chronically ill patients with a long history of suffering. To assess religiosity, the Munich Motives for Religiosity Inventory (MMRI) was used, a measure developed by Grom, Hellmeister, and Zwingmann [62]. The questionnaire consists of eight subscales that cover different motives of intrinsic religiosity: Moral self-control (α = 0.76), cooperative control of significant life events (α = 0.75), passive control of significant life events (α = 0.81), justice or reward for actions (α = 0.79), positive self-esteem (α = 0.85), gratitude and worship (α = 0.89), prosocial attitude and behavior (α = 0.84), and readiness to reflection (α = 0.71). The eight dimensions were theoretically derived from psychological motivational theories (e.g. self-efficacy, prosocial behavior).

To assess mental health, the well-known Symptom Check List (SCL-90-R, Derogatis 1977) was adopted, focusing on the Global Severity Index scale (GSI) as a measure of total symptom distress. Subjective well-being (SWB) has been measured with a four-item scale including items on distress (“At the present time, how upset or distressed have you been feeling?”), energy and health (“At the present time, how healthy and fit have you been feeling?”), emotional and psychological adjustment (“At the present time, how well do you feel that you are getting along emotionally and psychologically?”), and current life satisfaction (“At the present time, how satisfied are you with your current life?”).

To evaluate whether intrinsic religiosity does change during treatment paired sample t-tests was performed on MMRI measures. Table 2 shows means and standard deviations of MMRI subscales pre-and post-treatment as well as pre-post differences calculated with paired sample t-tests. Five subscales of the MMRI showed significant pre-post differences, at which “cooperative control”, “passive control” and “positive self-esteem” demonstrated the largest changes. All subscales with the exception of “moral self-control” and “justice or reward for actions” increased in numbers. Religiosity was found to be significantly changed during treatment.

To examine the degree of change of religiosity, symptomatic distress and subjective well-being during therapy, effect sizes (ESpre = Diffpre-post/SDpre) have been calculated. The mean of all MMRI subscales was used as an integrated measure of religiosity. Subjective well-being (ESpre = 1.34) and symptomatic distress (ESpre = 0.81) showed substantial changes over the treatment period, while changes in religiosity were small (ESpre = 0.15). This was expected because religiosity can be conceptualized as a personality characteristic/trait and is quite stable.

Pre-test correlations (Table 3) demonstrate that patients with higher religiosity tend to have better well-being. Religiosity is not associated with symptomatic distress at pre-test assessment. In contrast, subjective well-being was significantly and negatively associated with symptomatic distress, showing that patients with higher symptomatic burden have poorer well-being.

Post-test correlations (Table 4) exhibit basically the same pattern of relationship between religiosity, subjective well-being and symptomatic distress. The association between religiosity and subjective wellbeing was stronger and highly significant. In contrast to the pre-test findings there was a small but slightly significant negative correlation between religiosity and symptomatic distress.

To predict subjective well-being on post-test assessment, a hierarchical regression analysis was performed. In the first step, initial scores of subjective well-being, symptomatic distress, and initial MMRI mean scores were entered simultaneously as independent variables. In the next step, difference scores of symptomatic distress and difference scores of the MMRI mean were supplied. The results are summarized in Table 5. The first step explained 12% of the variance in subjective well-being. The second step explained another 38% of the variance. The standardized regression coefficients demonstrated that religiosity and also changes in religiosity play a significant role in predicting subjective well-being and lowering symptomatic distress.

First, the findings support the idea that religious faith is an important resource for religiously oriented patients [57] and is associated with therapeutic outcomes. Second, findings show that significant changes in subjective well-being are associated with religiosity. These results, then, provide empirical evidence that favors the integration of religious behavior, experience, and thinking into psychotherapy in order to enhance treatment outcomes in psychosomatic and psychiatric (in)patients.

5.3. Religious Patients Benefit from Religious Therapy by Religious and Non-Religious Therapists

There are only few studies which investigate the outcome of “religious therapies” [63-65]. The integration of religious elements into psychotherapy is typically used for religious patients. Rebecca Probst from the Department of Counseling Psychology, Portland, conducted a comparative study of the efficacy of religious and non-religious cognitive-behavioral therapy with religious and non-religious therapists on religious patients with clinical depression [65]. She hypothesized that religious cognitive-behavioral therapy (RCT) might be more effective for religious patients than standard cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) because of higher consistency of values and frameworks. Religious cognitive-behavioral therapy (RCT) gave religious rationales for the procedures, used religious arguments to counter irrational thoughts, and used religious imagery procedures according to a manual published by Probst 1988 [66]. Furthermore, the study was designed to determine whether non-religious therapists could successfully implement religious cognitive-behavioral therapy (RCT).

Focusing on pre- and post-treatment results, Probst et al. found that religious individuals receiving religious cognitive-behavioral therapy (RCT) reported more reduction in depression (BDI) and greater improvement in social adjustment (SAS) and general symptomatology (GSI, SCL-90-R) than patients in the standard cognitive-behavioral therapy group (CBT). Individuals in the pastoral counseling treatment group (PCT), which was included to control for the nonspecific effects of the treatment delivery system, also showed significant improvement at post-treatment and even outperformed standard CBT. This finding was similar to the results obtained with a non-clinical population [67].

The most surprising finding in the Probst study was a strong therapist-treatment interaction. The group showing the best performance on all measures was the RCT condition with the non-religious therapists (RCT-NT), whereas the group with the worst pattern of performance was the standard CBT with the non-religious therapists (CBT-NT). There was less difference in performance between the cognitive-behavioral therapy conditions for the religious therapists (RCT/CBT-RT). This pattern of therapist-treatment interaction suggests the following: 1. Effectiveness of CBT for religious patients delivered by non-religious therapists can be enhanced significantly by using a religious framework. 2. Impact of similarity of value orientation of therapists/therapy and patients on outcome of therapy seem to suggest that neither extreme value similarity nor extreme value dissimilarity facilitates outcome. Value similarity must be defined as a combination of the personal values of the therapist and the value orientation of the treatment. The RCT conditions with religious therapists and standard CBT with non-religious therapists show the most value similarity. Neither of them, however, showed high performance and was particularly relevant in this study.

6. Conclusions for the Integration of Religion and Spirituality into Therapy

The studies reviewed in this article support the integration of religion and spirituality into mental health care, psychiatry and psychotherapy. Many patients want service providers to address spiritual and religious issues during therapy [68]. Some fear that clinicians will “reduce” or “trivialize” their beliefs or that they will see them as a sign of pathology. This requires clinicians to take a respectful and individualized approach to patient's spiritual and religious background [69].

To develop competence in integrating religion and spirituality into mental health care, clinicians (including psychiatrists, psychotherapists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses) need professional training pertinent to the particular service setting [70]. Such training has to address the following topics: (1) Understanding the ways in which religion and spirituality relate to patients' overall well-being, evaluating whether patients' particular expression of spirituality is helpful or harmful for the recovery process. (2) Taking a spiritual history, developing the ability to talk with patients about spirituality in a manner that is neither intrusive nor reductive but which communicates respectful openness to a patient's unique spiritual experiences, both positive and negative. (3) Supporting religious and spiritual coping, e.g., prayer and meditation, reading psalms or other religious/spiritual literature, attending religious services. (4) Considering counter transference reactions that can be influenced by the therapists' religious or spiritual experiences [71]. (5) Delivering social and community resources, providing opportunities to expand the connections between religious or spiritual activities in the community and in the mental health program itself. (6) Learning when and how to make referrals to religious professionals, to faith-based programs or to centers of spiritual activity.

Mental health care programs integrating spiritual issues range from short-term psycho-educational groups to open-ended discussions of “religious issues” and the way they relate to mental health concerns. Programs illustrate possible forms of integration. For psychotherapy, the Probst study [65] as well as the Azahr studies [63,64] clearly indicate that the outcome in religious patients can be enhanced by integrating religious elements into therapy and that this can be successfully done by religious and non-religious therapists alike. Further studies need to investigate this promising area.

| Week | Topic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction | Facilitators give group members an overview of the group format and the topics. In addition, the group rules were reviewed and group members share their “personal spiritual journey” [43]. |

| 2 | Spiritual Resources | This session is intended to elicit members' ideas of personal and community spiritual resources [12]. The session begins by providing the group with definitions and examples of spiritual resources. The potential barriers to utilizing these resources are explored and discussed. |

| 3 | Spiritual Strivings | The primary objective is to have group members explore ways to create and achieve meaningful, realistic goals related to their spiritual journey. Facilitators discuss the importance of having strivings [52]. To promote discussion, group members generate personal lists of their strivings. |

| 4 | Spiritual Struggles | The overall goal is to emphasize the importance of expressing thoughts and feelings about spiritual struggles, validate and normalize anger with God or the Church, and reframe struggles as a time of personal growth. |

| 5 | Forgiveness of Others | Group members discuss the definition of forgiveness. Then they reflect on incidents in their life when they were hurt by another person or institution. Finally, steps towards forgiveness are briefly outlined [53]. |

| 6 | Hope | The primary goal is to explore spiritual strategies that can be used to hold on to hope [54]. Group members talk about the meaning of hope and reasons to retain hope. Major pathways used to foster hope are rituals, hymns, trusting that God has a greater purpose, and supporting each other. |

| 7 | Wrap-up | In the final session, the two permanent facilitators review the topics covered by the group and solicit feedback from group members. Emphasis is placed on maintaining confidentiality. |

| MMRI subscales | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | t (188) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral self-control | 4.46 (1.02) | 4.37 (1.06) | 1.58 |

| Cooperative control | 4.16 (1.02) | 4.39 (0.99) | 3.76*** |

| Passive control | 3.99 (1.09) | 4.22 (1.07) | 3.42*** |

| Justice/reward for actions | 2.89 (1.34) | 2.84 (1.33) | 0.68 |

| Positive self-esteem | 4.75 (1.04) | 5.03 (1.03) | 4.89*** |

| Gratitude and worship | 4.47 (1.08) | 4.65 (1.13) | 2.87** |

| Prosocial attitude/behavior | 4.49 (1.08) | 4.54 (1.13) | 0.83 |

| Readiness to reflection | 4.13 (1.03) | 4.28 (1.04) | 2.33* |

| Religiosity (MMRI mean) | 4.17 (0.78) | 4.29 (0.82) | 2.89** |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Religiosity (MMRI mean, t1) | (0.93) | ||

| 2. Subjective wellbeing (SWB, t1) | 0.17 * | (0.82) | |

| 3. Symptomatic distress (GSI, t1) | -0.08 | −0.43 *** | (0.97) |

Note. N = 189, reliabilities (Cronbach's α) in brackets;*p < 0.05,***p < 0.001.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Religiosity (MMRI mean, t2) | (0.95) | ||

| 2. Subjective wellbeing (SWB, t2) | 0.35 *** | (0.79) | |

| 3. Symptomatic distress (GSI, t2) | −0.15 * | −0.58 *** | (.97) |

Note. N = 189, reliabilities (Cronbach's α) in brackets;*p < 0.05,***p < 0.001.

| Variable | ΔR2 | β |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.12 | |

| Subjective well-being (SWB, t1) | 0.24 *** | |

| Symptomatic distress (GSI, t1) | −0.48 *** | |

| Religiosity (MMRI mean, t1) | 0.22 *** | |

| Step 2 | 0.38 | |

| ΔSymptomatic distress (ΔGSI) | −0.70 *** | |

| ΔReligiosity (ΔMMRI mean) | 0.24 *** | |

| All variables | 0.50 | |

Note. β = Standardized regression coefficients;***p < 0.001.

References

- V. Frankl. Men's Search for Meaning. New York, NY, USA: Washington Square Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- A. Blanch. “Integrating religion and spirituality in mental health: The promise and the challenge.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 30 (2007): 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- D.A. Matthiews. The Faith Factor: Proof of the Healing Power of Prayer. New York, NY, USA: Penguin Books, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Russinova, and A. Blanch. “Supported spirituality: A new frontier in the recovery-oriented mental health system.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 30 (2007): 247–249. [Google Scholar]

- R.D. Fallot. “Spirituality and religion in recovery from mental illness.” New Dir. Ment. Health Serv. 80 (1998): 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- K.N. Lindgren, and R.D. Coursey. “Spirituality and serious mental illness: A two-part study.” Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 18 (1995): 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- L. Tepper, S.A. Rogers, E.M. Coleman, and H.N. Malony. “The prevalence of religious coping among persons with persistent mental illness.” Psychiatr. Serv. 52 (2001): 660–665. [Google Scholar]

- H.G. Koenig. “Religious coping and depression in elderly hospitalized medically ill men.” Amer. J. Psychiat. 149 (1992): 1693–1700. [Google Scholar]

- B.H. Chang. “Religion and mental health among women veterans with sexual assault experience.” Int. J. Psychiat. Med. 31 (2001): 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- M. Baetz, D.B. Larson, G. Marcoux, R. Bowen, and R. Griffin. “Canadian psychiatric inpatient religious commitment: An association with mental health.” Can. J. Psychiatr. 47 (2002): 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- H.G. Koenig, L.K. George, and B.L. Peterson. “Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older patients.” Amer. J. Psychiat. 155 (1998): 536–542. [Google Scholar]

- K. Pargament. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- K. Pargament. “The bitter and the sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness.” Psychol. Inq. 13 (2002): 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- K. Pargament, H.G. Koenig, and L.M. Perez. “The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE.” J. Clin. Pyschol. 56 (2000): 519–543. [Google Scholar]

- E.G. Bush, M.S. Rye, C.R. Brant, E. Emery, K. Pargament, and C.A. Riessinger. “Religious coping with chronic pain.” Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedbac. 24 (1999): 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- G.L. Engel. “The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine.” Science 196 (1977): 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hefti. “Unser Therapiekonzept.” Infomagazin 5 (2003): 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- W.R. Miller, and C.E. Thoresen. Spirituality and health. In Integrating Spirituality into Treatment: Resources for Practitioners. Edited by W.R. Miller. Washington DC, USA: American Psychological Association, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- R. Mulligan, and T. Mulligan. “The science of religion in health care.” Veterans Health Syst. J., 1999, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- P.S. Richards, and A.E. Bergin. Toward religious and spiritual competency for mental health professionals. In Handbook of Psychotherapy and Religious Diversity. Edited by R. Richards, and A. Bergin. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association, 2000, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- K. Seybold, and P. Hill. “The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health.” Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 10 (2001): 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- D.A. Longo, and M.S. Peterson. “The role of spirituality in psychosocial rehabilitation.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 25 (2002): 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- W.P. Sullivan. “Recoiling, regrouping, and recovering: First-person accounts of the role of spirituality in the course of serious mental illness.” New Dir. Ment. Health Serv. 80 (1998): 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- W.A. Anthony. “The principle of personhood: The field's transcendent principle.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 27 (2004): 205. [Google Scholar]

- B. Cosar, N. Kocal, Z. Arikan, and E. Isik. “Suicide attempts among Turkish psychiatric patients.” Can. J. Psychiatr. 42 (1997): 1072–1075. [Google Scholar]

- J. Mickley, V. Carson, and L. Soeken. “Religion and adult mental health: State of the science in nursing.” Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 16 (1995): 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- A.E. Bergin, K.S. Masters, and P.S. Richards. “Religiousness and mental health reconsidered: A study of an intrinsically religious sample.” J. Couns. Psychol. 34 (1987): 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- F. Jahangir. “Third force therapy and its impact on treatment outcome.” Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 5 (1995): 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- D. Pardini, T.G. Plante, and A. Sherman. “Strength of religious faith and its association with mental health outcomes among recovering alcoholics and addicts.” J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 19 (2001): 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- J. Walsh. “The impact of schizophrenia on clients' religious beliefs: Implications for families.” Fam. Soc. 76 (1995): 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- D. MacGreen. “Spirituality as a coping resource.” Behav. Ther. 20 (1997): 28. [Google Scholar]

- R.D. Fallot. Spirituality in trauma recovery. In Sexual Abuse in the Lives of Women Diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness. Edited by M. Harris. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997, pp. 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- S.J. Onken, J.M. Dumont, P. Ridgway, D.H. Dornan, and R.O. Ralph. “Mental Health Recovery: What Helps and What Hinders? National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD).” Res. Rep., 2002, 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- J.J. Exline, A.M. Yali, and M. Lobel. “When God disappoints: Difficulty forgiving God and its role in negative emotion.” J. Health Psychol. 4 (1999): 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- J.J. Exline, A.M. Yali, and W.C. Sanderson. “Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality.” J. Clin. Psychol. 56 (2000): 1481–1496. [Google Scholar]

- K.E. Bussema, and E.F. Bussema. “Is there a balm in Gilead? The implications of faith in coping with a psychiatric disability.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 24 (2000): 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- J.J. Exline. “Stumbling blocks on the religious road: Fractured relationships, nagging vices, and the inner struggle to believe.” Psychol. Inq. 13 (2002): 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- S. Mohr, P-Y. Brandt, L. Borras, C. Gilliéron, and P. Huguelet. “Toward an integration of spirituality and religiousness into the psychosocial dimension of schizophrenia.” Am. J. Psychiatr. 163 (2006): 1952–1959. [Google Scholar]

- P. Huguelet, S. Mohr, P-Y. Brandt, L. Borras, and C. Gillieron. “Spirituality and religious practices among outpatients with schizophrenia and their clinicians.” Psychiatr. Services 57 (2006): 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- A. Längle. “The art of involving the person—fundamental existential motivations as the structure of the motivational process.” Eur. Psychother. 4 (2003): 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- T. Schmidt, and S. Adami. Depression und Glaube—eine qualitative Studie an der Universität Freiburg. Freiburg, Germany: Diplomarbeit, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hefti. Integrating Spiritual Issues into Therapy. In Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry. Edited by P. Huguelet, and H.G. Koenig. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 244–267. [Google Scholar]

- N.C. Kehoe. “A therapy group and spirituality issues fro patients with chronic mental illness.” Psychiatr. Services 50 (1999): 1081–1083. [Google Scholar]

- G. Gallup. The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion. Wilmington, DE, USA: Scholarly Resources, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- A.E. Bergin, and J.P. Jensen. “Religiosity of psychotherapists: A national survey.” Psychotherapy 27 (1990): 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- G. Reger, A. Wong-McDonald, and R. Liberman. “Psychiatric rehabilitation in a community mental health center.” Psychiatr. Serv. 54 (2003): 1457–1459. [Google Scholar]

- A. Wong-McDonald. “Spirituality and psychosocial rehabilitation: Empowering persons with serious psychiatric disabilities at an inner-city community program.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 30 (2007): 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- N. Revheim, and W.M. Greenberg. “Spirituality matters: Creating a time and place for hope.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 30 (2007): 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- S.Y. Weintraub. From the depths: Psalms as a spiritual reservoir in difficult times. In The Outstretched Arm. New York, NY, USA: National Center for Jewish Healing of JBFCS, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- S. Folkman, M. Chesney, L. McKusick, G. Ironson, D.S. Johnson, and T.J. Coates. Translation coping theory into an intervention. In The Social Context of Coping. Edited by J. Eckenrode. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- R.S. Phillips, R. Lakin, and K. Pargament. “Development and implementation of a spiritual issues psychoeducational group for those with serious mental illness.” Community Ment. Health J. 38 (2002): 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- R.A. Emmons. The Psychology of Ultimate Concerns. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- R.D. Enright, and R.P. Fitzgibbons. Helping Clients Forgive. An Empirical Guide for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- C.E. Yahne, and W.R. Miller. Evoking Hope. In Integrating Spirituality into Treatment. Edited by W.R. Miller. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999, pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- P.S. Richards, and A.E. Bergin. A Spiritual Strategy for Counseling and Psychotherapy. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- M. Allemand, and M. Kliegel. “Religiosity and its relation to therapeutic changes in subjective well-being and mental health in a Swiss inpatient sample.” Paper presented at the Psychology of Religion Conference, Glasgow, UK, 28-31 August 2003.

- H.G. Koenig, and J.T. Pritchett. Religion and psychotherapy. In Handbook of Religion and Mental Health. Edited by H.G. Koenig. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, 1998, pp. 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- T.G. Plante, and A.C. Sherman. Faith and Health: Psychological Perspectives. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- K. Grawe. Psychologische Therapie. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- K. Grawe, and M. Grawe-Gerber. “Ressourcenaktivierung. Ein primäres Wirkprinzip der Psychotherapie.” Psychotherapeut 2 (1999): 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- K.I. Howard, R.J. Lueger, M.S. Maling, and Z. Martinovich. “A phase model of psychotherapy outcome: Causal mediation of change.” J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 61 (1993): 678–685. [Google Scholar]

- B. Grom, G. Hellmeister, and C. Zwingmann. Münchner Motivationspsychologisches Religiositäts-Inventar (MMRI). Entwicklung eines neuen Meßinstruments für die religionspsychologische Forschung. In Religion und Religiosität zwischen Theologie und Psychologie. Edited by C. Henning, and E. Nestler. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Lang, 1998, pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- M. Azahr, S.L. Varma, and A.S. Dharap. “Religious psychotherapy in anxiety disorders.” Acta Psychiat. Scand. 90 (1994): 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- M. Azahr, and S.L. Varma. “Religious psychotherapy in depressive patients.” Psychother. Psychosom. 63 (1995): 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- L.R. Propst, R. Ostrom, P. Watkins, T. Dean, and D. Mashburn. “Comparative efficacy of religious and nonreligious cognitive-behavior therapy for the treatment of clinical depression in religious individuals.” J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 60 (1992): 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- L.R. Probst. Psychotherapy in a Religious Framework: Spirituality in the Emotional Healing Process. New York, NY, USA: Human Sciences Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- L.R. Propst. “The comparative efficacy of religious and nonreligious imagery for the treatment of mild depression in religious individuals.” Cognitive Ther. Res. 4 (1980): 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- R. D'Souza. “Do patients expect psychiatrists to be interested in spiritual issues? ” Australas. Psychiatr. 10 (2002): 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- T.G. Plante. “Integrating spirituality and psychotherapy: Ethical issues and principles to consider.” J. Clin. Psychol. 63 (2007): 891–902. [Google Scholar]

- R.D. Fallot. “Spirituality and religion in recovery: Some current issues.” Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 30 (2007): 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- H.G. Koenig. Spirituality in Patient Care: Why, How, When and What. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Templeton Foundation Press, 2002, p. 165. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hefti, R. Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Mental Health Care, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Religions 2011, 2, 611-627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040611

Hefti R. Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Mental Health Care, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Religions. 2011; 2(4):611-627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040611

Chicago/Turabian StyleHefti, René. 2011. "Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Mental Health Care, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy" Religions 2, no. 4: 611-627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040611