Balancing Acts: Unveiling the Dynamics of Revitalization Policies in China’s Old Revolutionary Areas of Gannan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Policy Background and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Policy Background

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

3. Method and Variable Setting

3.1. Model Specification

- Step 1: PSM Matching

- 2: DID Estimation

3.2. Variable Setting

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Data

4. Empirical Results

4.1. PSM Processing

4.2. PSM-DID Results

4.2.1. Baseline Results

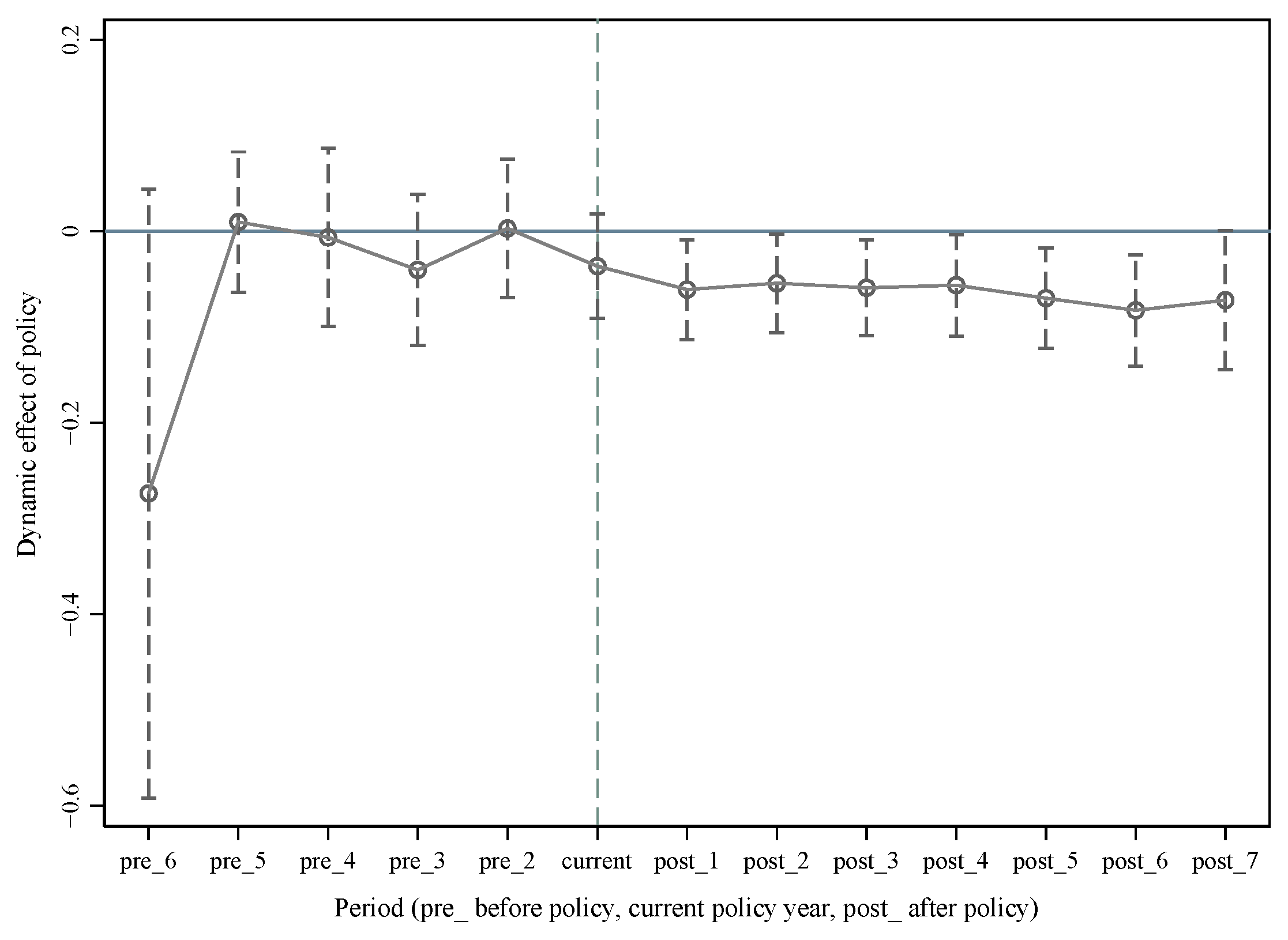

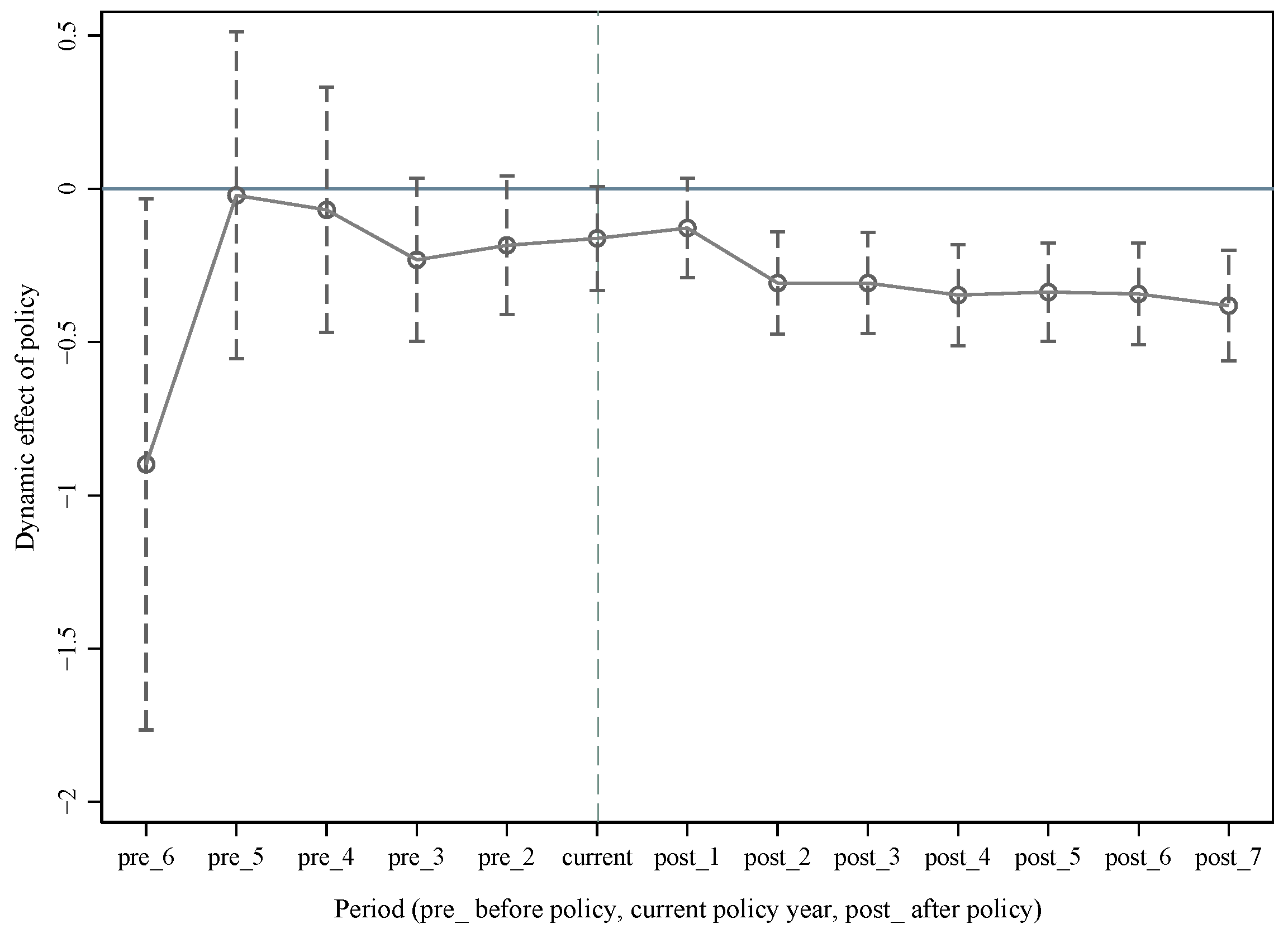

4.2.2. Parallel Trends Assumptions Test

4.2.3. Robustness Checks

4.2.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.2.5. Mechanism Test

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L. Place-based policies, creation, and agglomeration economies: Evidence from China’s economic zone program. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2019, 11, 325–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y. Demystifying the geography of income inequality in rural China: A transitional framework. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Heterogeneity Perspective on the Dynamic Identification of Low-Income Groups and Quantitative Decomposition of Income Increase: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, J. Urbanization forces driving rural urban income disparity: Evidence from metropolitan areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Fang, P.; Chen, S. Can place-based policies reduce urban-rural income inequality? Evidence from China’s Old Revolutionary Development Program based on county-level data. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wu, T.; Li, H.M. The drivers of air pollution in the development of western China: The case of Sichuan province. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.B.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.Y. The status quo, causes and countermeasures of economic differentiation in North and South China: A new trend that needs attention. J. Hebei Univ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 40, 801–808. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, M. Targeted Business Incentives and Local Labor Markets. J. Hum. Resour. 2013, 48, 311–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bernini, C.; Pellegrini, G. How are Growth and Productivity in Private Firms Affected by Public Subsidy? Evidence from a Regional Policy. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2011, 41, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, A. Regional development through place-based policies: Evidence from a spatial discontinuity. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 130, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E.; Pollio, C.; Prota, F. The impacts of spatially targeted programmes: Evidence from Guangdong. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Zhang, W. Industrial structure upgrading, urbanization and urban-rural income disparity: Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P.; Moretti, E. People, places, and public policy: Some simple welfare economics of local economic development programs. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2014, 6, 629–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zhou, C.; Wen, H. Improving the consumer welfare of rural residents through public support policies: A study on old revolutionary areas in China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 91, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, O.; Koenen, J.; Lohse, T. Evaluating a place-based innovation policy: Evidence from the innovative Regional Growth Cores Program in East Germany. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2019, 79, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Xue, B.; Yang, J.; Lu, C. Effects of the Northeast China revitalization strategy on regional economic growth and social development. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 791–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shao, S.; Xu, L.; Yang, L. Can regional development plans promote economic growth? City-level evidence from China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 83, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, M.; Xu, X. Status and path of intergenerational transmission of poverty in rural China: A human capital investment perspective. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Chen, Y.G.; Kong, F. The role of place-based policies on carbon emission: A quasi-natural experiment from China’s old revolutionary development program. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Tan, R.; He, X. How does economic agglomeration affect energy efficiency in China? Evidence from endogenous stochastic frontier approach. Energy Econ. 2022, 108, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Ma, G.; Qin, C.; Wang, L. Place-based policies, state-led industrialisation, and regional development: Evidence from China’s Great Western Development Programme. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 123, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Q. Effect of Western Development Strategy on carbon productivity and its influencing mechanisms. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 4963–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I.; Common, M.S.; Barbier, E.B. Economic growth and environmental degradation: The environmental Kuznets curve and sustainable development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Meng, X.; Tao, R.; Umar, M. Policy turmoil in China: A barrier for FDI flows? Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17, 1617–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishti, M.Z.; Alam, N.; Murshed, M.; Rehman, A.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Pathways towards environmental sustainability: Exploring the influence of aggregate domestic consumption spending on carbon dioxide emissions in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 45013–45030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassoued, M. Control of corruption, microfinance, and income inequality in MENA countries: Evidence from panel data. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, C.K. Financial reforms and corruption: Which dimensions matter? Int. Rev. Financ. 2020, 20, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.H.; Samargandi, N.; Ahmed, A. Economic Development, Energy Consumption, and Climate Change: An Empirical Account from Malaysia. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2021; Volume 45, pp. 397–423. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J.; Poterba, J. Tax Incentives and the Decision to Purchase Health Insurance: Evidence from the Self-employed. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 701–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Cheng, S.; Cui, J. Environmental and economic effects of China’s carbon market pilots: Empirical evidence based on a DID model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, M.; Liu, Q. How does targeted poverty alleviation policy influence residents’ perceptions of rural living conditions? A study of 16 villages in Gansu Province, Northwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, O.P.; Picci, L.; Scorcu, A.E. Saving, Growth, and Investment; A Macroeconomic Analysis Using a Panel of Countries. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2000, 82, 182–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H. Analysis of the impact of tourism development on the urban-rural income gap: Evidence from 248 prefecture-level cities in China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 5, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Jiang, L. Promoting sustainable development in less developed regions: An empirical study of old revolutionary base areas in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H. Aggregate consumption function and income distribution effect: Some evidence from developing countries. World Dev. 1987, 15, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Document | Main Content |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | ⟪Opinions of the State Council on Supporting the Revitalization and Development of Gannan and Other Former Central Soviet Areas⟫ | Policy support and organizational leadership have been strengthened in terms of improving livelihood issues, infrastructure development, cultivation of special industries, ecological and environmental protection, public services, and optimization of institutional reforms. |

| 2013 | ⟪Implementation Programme of the Central State Organ and Related Units’ Oral Support to Gannan and Other Former Central Soviet Areas⟫ | 52 state organs and related units, counterpart support to pick up Ganzhou City, Ji’an City, and Fuzhou City, a total of 31 counties (cities and districts), including talent and technical support, business guidance support, and cracking development problems. |

| 2014 | ⟪Plan for the Revitalization and Development of the Former Central Soviet Area in Gan, Fujian, and Guangdong Province⟫ | Coordinate regional spatial layout; strengthen industrial system construction; basic design construction; increase ecological protection; promote social development and poverty alleviation and development; coordinate urban and rural development; improve regional cooperation mechanisms; and establish safeguards. |

| 2021 | ⟪Work Programme of the Central State Organs and Related Units in Support of Gannan and Other Former Central Soviet Areas in the New Era⟫ | The counterpart support units include 63 central state organs and related units, and the recipient areas include a total of 43 counties (cities and districts) under the jurisdiction of Ganzhou City, Ji’an City and Fuzhou City in Jiangxi Province and Longyan City and Sanming City in Fujian Province. |

| 2021 | ⟪Implementation Opinions on Further Promoting the Revitalization and Development of the Old Revolutionary Areas in Jiangxi in the New Era⟫ | Implementation of the rural revitalization strategy: development of modern agriculture, infrastructure construction, cultivation of advantaged industries, docking of regional strategies, upgrading of ecological quality, green transformation, enhancement of people’s well-being, and strengthening of policy protection. |

| Variable | Definition | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained Variables | |||

| GDP per capita | GDP per capita (logarithm) | 9.7440 | 0.6514 |

| Farmers’ income | Disposable income of farmers (logarithm) | 8.7367 | 0.5769 |

| Farmers’ income gap | The proportion of the disposable income of farmers in Jiangxi Province and ORA counties (districts and cities) | 1.2954 | 0.3569 |

| Core Explanatory Variables | |||

| Revitalization Policy | Dummy variable (0, 1) | 0.2166 | 0.4123 |

| Investment Level | Total fixed asset investment per capita (logarithm) | 8.0634 | 1.0570 |

| Resident saving level | Per capita residential savings deposit balance (taking logarithm) | 8.1358 | 0.7914 |

| Fiscal revenue level | Fiscal revenue per capita (logarithm) | 6.2621 | 0.8276 |

| Control Variables | |||

| Government Expenditure | Financial expenditure within the general public budget per capita (logarithm) | 7.0037 | 0.7786 |

| Industrialization level | Value-added of secondary industry per capita (logarithm) | 7.6302 | 0.7804 |

| Advanced industrial structure | Value-added of tertiary industry per capita (logarithm) | 7.3001 | 0.7517 |

| Opening up level | Amount of actual foreign capital utilized per capita (logarithm) | 5.2456 | 0.7431 |

| Variables | Overall | Experimental Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2019 | 2006–2011 | 2013–2019 | 2006–2011 | 2013–2019 | |

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| GDP per capita (yuan) | 21,321.41 (13.44%) | 10,639.54 (15.03%) | 26,718.43 (8.51%) | 11,721.08 (15.65%) | 32,846.64 (9.98%) |

| Farmers’ income (yuan) | 7443.16 (11.64%) | 3194.87 (9.42%) | 8704.51 (11.43%) | 4635.90 (11.29%) | 11,931.28 (8.53%) |

| Investment Level (million yuan) | 735,478.80 (19.59%) | 183,507.80 (24.03%) | 802,029.50 (11.19%) | 357,075.10 (23.23%) | 1,404,346.40 (12.22%) |

| Resident saving level (million yuan) | 672,497.10 (15.48%) | 311,073.20 (18.39%) | 988,522.90 (12.48%) | 302,079.90 (16.06%) | 1,015,485.23 (11.65%) |

| Fiscal revenue level (million yuan) | 103,138.20 (17.37%) | 37,435.03 (19.83%) | 122,271.40 (8.47%) | 44,290.53 (24.41%) | 184,250.60 (8.44%) |

| Government Expenditure (million yuan) | 210,521.60 (17.79%) | 86,178.32 (18.80%) | 311,021.60 (12.20%) | 93,670.78 (23.64%) | 320,784.41 (10.10%) |

| Industrialization level (million yuan) | 392,759.50 (13.94%) | 176,189.70 (19.31%) | 445,231.10 (5.39%) | 232,068.70 (21.18%) | 633,040.12 (7.39%) |

| Advanced industrial structure (million yuan) | 282,038.70 (14.80%) | 144,439.90 (14.57%) | 423,014.20 (11.76%) | 123,570.30 (14.10%) | 413,783.40 (12.83%) |

| Opening up level (million yuan) | 35,090.18 (9.10%) | 26,014.7 (2.37%) | 43,197.85 (10.37%) | 19,001.01 (10.47%) | 50,074.80 (10.72%) |

| Variable | Experimental Group | Control Group | Standardized Deviation (%) | Decrease (%) | T-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revitalization Policy | U | 8.3234 | 7.9791 | 36.6 | 57.8 | 3.13 | 0.002 |

| M | 8.3519 | 8.4971 | −15.4 | −1.06 | 0.292 | ||

| Investment Level | U | 8.5817 | 7.9912 | 84.2 | 89.1 | 7.49 | 0.000 |

| M | 8.5513 | 8.6158 | −9.2 | −0.62 | 0.538 | ||

| Resident saving level | U | 6.6014 | 6.1521 | 64.6 | 81 | 5.31 | 0.000 |

| M | 6.5888 | 6.6743 | −12.3 | −0.93 | 0.352 | ||

| Fiscal revenue level | U | 7.5177 | 6.837 | 106.5 | 88.5 | 8.97 | 0.000 |

| M | 7.4759 | 7.5544 | −12.3 | −0.91 | 0.362 | ||

| Government Expenditure | U | 7.8139 | 7.5706 | 33.7 | 49.3 | 2.99 | 0.003 |

| M | 7.8331 | 7.9565 | −17.1 | −1.18 | 0.239 | ||

| Industrialization level | U | 7.7687 | 7.1482 | 94.7 | 90.3 | 8.4 | 0.000 |

| M | 7.7242 | 7.7846 | −9.2 | −0.69 | 0.488 | ||

| Advanced industrial structure | U | 5.4678 | 5.1736 | 41.6 | 80.8 | 3.82 | 0.000 |

| M | 5.4603 | 5.5169 | −8 | −0.61 | 0.543 |

| Matching Method | Pseudo-R2 | LR Statistic | Mean Value of Deviation (%) | Median Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | 0.352 | 192.22 *** | 66 | 64.6 |

| Nearest Neighbor Matching Method | 0.013 | 3.73 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Caliper Matching Method | 0.007 | 1.67 | 6.6 | 7 |

| Kernel Matching Method | 0.012 | 3.5 | 11.9 | 12.3 |

| Variable | (1): Economic Growth | (2): Farmers’ Income | (3): Farmers’ Income Gap | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Revitalization Policy | −0.0564 *** | 0.0167 | 0.130 *** | 0.0266 | −0.218 *** | 0.0442 |

| Investment Level | 0.0950 *** | 0.0317 | −0.0141 | 0.0506 | 0.0157 | 0.0840 |

| Resident saving level | −0.0625 * | 0.0331 | 0.361 *** | 0.0528 | −0.581 *** | 0.0877 |

| Fiscal revenue level | 0.0270 | 0.0416 | 0.0288 | 0.0664 | −0.0121 | 0.110 |

| Government Expenditure | 0.0666 ** | 0.0338 | −0.135 ** | 0.0539 | 0.221 ** | 0.0896 |

| Industrialization level | 0.431 *** | 0.0273 | 0.143 *** | 0.0435 | −0.233 *** | 0.0722 |

| Advanced industrial structure | 0.171 *** | 0.0164 | −0.0196 | 0.0262 | 0.0226 | 0.0435 |

| Opening up level | −0.0161 | −0.0161 | 0.0922 *** | 0.0256 | −0.153 *** | 0.0426 |

| Constant | 4.339 *** | 0.3940 | 4.623 *** | 0.629 | 6.601 *** | 1.044 |

| Time Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| R2 | 0.990 | 0.9779 | 0.5222 | |||

| Variable | (4): Economic Growth | (5): Farmers’ Income | (6): Farmers’ Income Gap | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Revitalization Policy | −0.0433 *** | 0.0109 | 0.0869 *** | 0.0185 | −0.164 *** | 0.0290 |

| Investment Level | 0.0153 | 0.0132 | 0.0144 | 0.0223 | −0.0222 | 0.0349 |

| Resident saving level | −0.0424 | 0.0261 | 0.275 *** | 0.0443 | −0.458 *** | 0.0692 |

| Fiscal revenue level | 0.0941 *** | 0.0297 | −0.0433 | 0.0504 | 0.102 | 0.0788 |

| Government Expenditure | 0.0179 | 0.0211 | 0.0328 | 0.0358 | 0.00190 | 0.0559 |

| Industrialization level | 0.479 *** | 0.0186 | 0.0724 ** | 0.0315 | −0.124 ** | 0.0493 |

| Advanced industrial structure | 0.198 *** | 0.0152 | −0.0236 | 0.0258 | 0.0380 | 0.0403 |

| Opening up level | 0.000709 | 0.0101 | 0.0495 *** | 0.0171 | −0.0865 *** | 0.0267 |

| Constant | 4.027 *** | 0.289 | 5.452 *** | 0.489 | 5.074 *** | 0.765 |

| Time Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| R-squared | 0.994 | 0.980 | 0.378 | |||

| Variable | (7): Advanced to 2008 | (8): Advanced to 2009 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Growth | Farmers’ Income | Farmers’ Income Gap | Economic Growth | Farmers’ Income | Farmers’ Income Gap | |

| Revitalization Policy | −0.000100 (0.0139) | 0.00275 (0.0237) | −0.0235 (0.0375) | −0.00725 (0.0132) | 0.0160 (0.0225) | −0.0447 (0.0355) |

| Investment Level | 0.00573 (0.0132) | 0.0334 (0.0225) | −0.0572 (0.0356) | 0.00667 (0.0133) | 0.0315 (0.0227) | −0.0526 (0.0358) |

| Resident saving level | −0.0393 (0.0266) | 0.269 *** (0.0454) | −0.445 *** (0.0717) | −0.0384 (0.0266) | 0.267 *** (0.0454) | −0.440 *** (0.0717) |

| Fiscal revenue level | 0.0755 ** (0.0305) | −0.00495 (0.0521) | 0.0210 (0.0824) | 0.0743 ** (0.0300) | −0.00327 (0.0511) | 0.0235 (0.0807) |

| Government Expenditure | 0.0516 *** (0.0199) | −0.0344 (0.0340) | 0.125 ** (0.0537) | 0.0476 ** (0.0210) | −0.0262 (0.0357) | 0.105 * (0.0564) |

| Industrialization level | 0.474 *** (0.0190) | 0.0812 ** (0.0323) | −0.139 *** (0.0511) | 0.475 *** (0.0190) | 0.0797 ** (0.0323) | −0.136 *** (0.0511) |

| Advanced industrial structure | 0.204 *** (0.0154) | −0.0360 (0.0263) | 0.0616 (0.0415) | 0.204 *** (0.0154) | −0.0364 (0.0263) | 0.0627 (0.0414) |

| Opening up level | 0.0157 (0.0101) | 0.0201 (0.0172) | −0.0353 (0.0272) | 0.0133 (0.0105) | 0.0248 (0.0179) | −0.0446 (0.0283) |

| Constant | 3.929 *** (0.297) | 5.640 *** (0.506) | 4.781 *** (0.800) | −0.00725 (0.0132) | 5.608 *** (0.503) | 4.817 *** (0.794) |

| Time Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.994 | 0.979 | 0.3326 | 0.994 | 0.979 | 0.3344 |

| Variable | (9): Economic Growth | (10): Farmers’ Income | (11): Farmers’ Income Gap | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q25 | q50 | q75 | q25 | q50 | q75 | q25 | q50 | q75 | |

| Revitalization Policy | −0.0497 (0.0362) | −0.0560 ** (0.0262) | −0.0639 * (0.0351) | 0.0987 ** (0.0494) | 0.120 (0.0839) | 0.165 (0.228) | −0.271 * (0.140) | −0.209 *** (0.0800) | −0.170 * (0.0923) |

| Investment Level | 0.123 (0.0778) | 0.0967 * (0.0566) | 0.0630 (0.0756) | −0.0468 (0.0816) | −0.0244 (0.138) | 0.0222 (0.377) | −0.0426 (0.227) | 0.0264 (0.129) | 0.0689 (0.150) |

| Resident saving level | −0.0771 (0.0707) | −0.0633 (0.0513) | −0.0459 (0.0687) | 0.254 *** (0.0849) | 0.327 ** (0.146) | 0.479 (0.394) | −0.770 *** (0.238) | −0.547 *** (0.139) | −0.409 *** (0.157) |

| Fiscal revenue level | 0.0107 (0.0818) | 0.0260 (0.0594) | 0.0455 (0.0795) | 0.0172 (0.110) | 0.0252 (0.186) | 0.0417 (0.509) | −0.0268 (0.308) | −0.00938 (0.175) | 0.00133 (0.203) |

| Government Expenditure | 0.0620 (0.0781) | 0.0663 (0.0567) | 0.0718 (0.0759) | −0.120 (0.0957) | −0.130 (0.162) | −0.152 (0.442) | 0.236 (0.273) | 0.218 (0.155) | 0.208 (0.181) |

| Industrialization level | 0.438 *** (0.0729) | 0.431 *** (0.0529) | 0.423 *** (0.0709) | 0.124 * (0.0664) | 0.137 (0.112) | 0.163 (0.307) | −0.248 (0.185) | −0.230 ** (0.105) | −0.219 * (0.122) |

| Advanced industrial structure | 0.203 * (0.107) | 0.173 ** (0.0776) | 0.134 (0.104) | −0.0166 (0.0403) | −0.0187 (0.0682) | −0.0229 (0.186) | 0.0322 (0.113) | 0.0208 (0.0642) | 0.0137 (0.0747) |

| Opening up level | −0.00731 (0.0422) | −0.0156 (0.0307) | −0.0261 (0.0410) | 0.104 ** (0.0486) | 0.0958 (0.0823) | 0.0794 (0.224) | −0.130 (0.136) | −0.157 ** (0.0776) | −0.174 * (0.0901) |

| Time Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variable | Investment Level | Resident Saving Level | Fiscal Revenue Level | Government Expenditure | Industrialization Level | Advanced Industrial Structure | Opening Up Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revitalization Policy | 0.102 * (0.0550) | −0.0390 (0.0411) | 0.00613 (0.0240) | −0.262 *** (0.0541) | −0.0944 (0.0598) | −0.118 *** (0.0414) | −0.475 *** (0.0778) |

| policy | 1.396 *** (0.0367) | 1.138 *** (0.0227) | 1.244 *** (0.0179) | 1.448 *** (0.0342) | 1.019 *** (0.0507) | 1.133 *** (0.0277) | 0.936 *** (0.0709) |

| dt | −0.726 *** (0.212) | −0.0213 (0.156) | −0.0418 (0.114) | −0.146 (0.124) | −0.318 * (0.177) | 0.125 (0.151) | 0.315 (0.209) |

| Constants | 7.552 *** (0.132) | 7.504 *** (0.0922) | 6.309 *** (0.0791) | 5.561 *** (0.0728) | 7.207 *** (0.0969) | 6.628 *** (0.0896) | 4.692 *** (0.124) |

| Observations | 490 | 490 | 490 | 490 | 490 | 490 | 490 |

| R-squared | 0.7308 | 0.7435 | 0.7621 | 0.7898 | 0.7133 | 0.7223 | 0.6059 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, W.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Qiu, H. Balancing Acts: Unveiling the Dynamics of Revitalization Policies in China’s Old Revolutionary Areas of Gannan. Agriculture 2024, 14, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030354

Liao W, Yuan R, Zhang X, Li N, Qiu H. Balancing Acts: Unveiling the Dynamics of Revitalization Policies in China’s Old Revolutionary Areas of Gannan. Agriculture. 2024; 14(3):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030354

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Wenmei, Ruolan Yuan, Xu Zhang, Na Li, and Hailan Qiu. 2024. "Balancing Acts: Unveiling the Dynamics of Revitalization Policies in China’s Old Revolutionary Areas of Gannan" Agriculture 14, no. 3: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030354