Effects of Stocking Density on Milk Fatty Acids Composition and Oxidative Stability of Mid- and Late-Lactating Dairy Cows

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

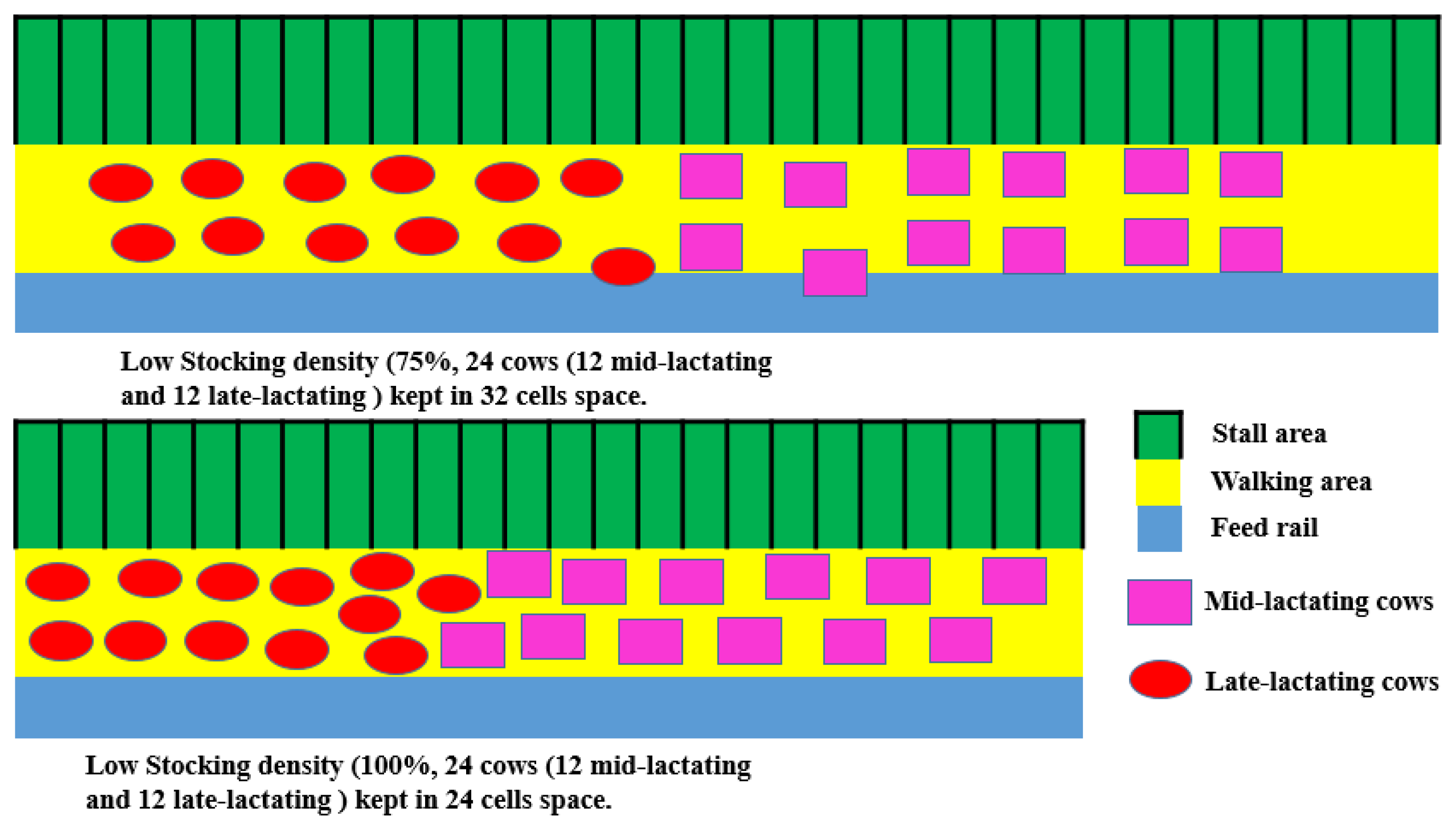

2.1. Animals, Diets and Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection and Measurement

2.2.1. Feed Sample

2.2.2. Lactation Performance and Body Weight Change

2.2.3. Plasma Variables

2.2.4. Milk FAs Determination

2.2.5. Oxidation Capacity Variables in Milk

2.3. Calculation and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aigster, A.; Sims, C.; Staples, C.; Schmidt, R.; O’Keefe, S.F. Comparison of cheeses made from milk having normal and high oleic fatty acid compositions. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbright, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary heart disease: Seven dietary factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.A.; Griinari, J.M.; Kennelly, J.J. Effect of safflower oil, flaxseed oil, monensin, and vitamin E on concentration of conjugated linoleic acid in bovine milk fat. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.P.; Wang, J.Q.; Dhiman, T.R.; Liu, S.J. Effectiveness of oils rich in linoleic and linolenic acids to enhance conjugated linoleic acid in milk from dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmley, E.; Nicholson, J.W.G. Influence of dietary fat source on oxidative stability and fatty acid composition of milk from cows receiving a low or high level of dietary vitamin E. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 74, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksombat, W.; Thanh, L.P.; Meeprom, C.; Mirattanaphrai, R. Effects of linseed oil or whole linseed supplementation on performance and milk fatty acid composition of lactating dairy cows. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Bu, D.; Cui, H.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, L. Effects of different fat mixtures on milk fatty acid composition and oxidative stability of milk fat. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2013, 185, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, J.X.; Cao, H.; Guo, F.C.; Vázquez-Añón, M. Effect of different rumen-inert fatty acids supplemented with a dietary antioxidant on performance and antioxidative status of early-lactation cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 3738–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.L.; Yang, D.P.; Chen, P.; Dong, W.X.; Wang, D.M. Supplementation with selenium and vitamin E improves milk fat depression and fatty acid composition in dairy cows fed fat diet. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 21, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelder, T.L. The impact of head gates and overcrowding on production and behavior patterns of lactating dairy cows. In Dairy Housing and Equipment Systems. Managing and Planning for Profitability; Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service: Camp Hill, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.J.; Albright, J.L. Effect of animal grouping on feeding behavior and intake of cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, E156–E163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczel, P.D.; Klaiber, L.B.; Butzler, R.E.; Klaiber, L.M.; Dann, H.M.; Mooney, C.S.; Grant, R.J. Short-term increases in stocking density affect the lying and social behavior, but not the productivity, of lactating Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 4298–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.X.; Shao, D.F.; Li, S.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Azarfar, A.; Cao, Z.J. Effects of stocking density on behavior, productivity, and comfort indices of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3709–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fustini, M.; Galeati, G.; Gabai, G.; Mammi, L.E.; Bucci, D.; Baratta, M.; Accorsi, P.A.; Formigoni, A. Overstocking dairy cows during the dry period affects dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol secretion. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 100, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner-Storch, A.M.; Palmer, R.W.; Kammel, D.W. Factors affecting stall use for different freestall bases. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists International. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Arlington, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods of dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, A.A.; Carroll, W.E.; Sterling, R.E.; Davis, H.A.; Ware, A.G. Use of the Berthelot reaction in the automated analysis of serum urea nitrogen. Clin. Chem. 1966, 12, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Mayne, C.S.; Patterson, D.C.; Agnew, R.E. Prediction of body weight and empty body composition using body size measurements in lactating dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 2009, 124, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 1969, 244, 6049–6055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.; Stain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Tan, Y.L.; Cao, L.Y.; Wu, G.Y.; Xu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, D.F. Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in different forms of schizophrenia treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 81, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopster, H.; Van der Werf, J.T.; Erkens, J.H.; Blokhuis, H.J. Effects of repeated jugular puncture on plasma cortisol concentrations in loose-housed dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, A.; Radin, N.S. Lipid extraction of tissues with a low-toxicity solvent. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 90, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, A.L.; Preseault, C.L.; Rico, J.E.; DeLand, K.E.; Allen, M.S. Feeding a C16:0-enriched fat supplement increased the yield of milk fat and improved conversion of feed to milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 6650–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goth, L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta 1991, 196, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STATISTICAL ANALYSIS SYSTEM Institute. SAS User’s Guide: Statistics, version 8.01; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pence, K.J. The Effects of Dietary Forage, Social Hierarchy, and Stocking Density on Stress in Lactating Cows during Relocation [Electronic Resource]. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Telezhenko, E.; Von Keyserlingk, M.A.; Talebi, A.; Weary, D.M. Effect of pen size, group size, and stocking density on activity in freestall-housed dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3064–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, J.L.; Gee, G. Kinetic studies in the chemistry of rubber and related materials. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1946, 42, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Murcia, M.A.; Chirico, S.; Aruoma, O.I. Free radicals and antioxidants in food and in vivo: What they do and how they work. CRC Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1995, 35, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlelie, J.; Venardos, V.L.; Clifton, V.L.; Gude, N.M.; Clarke, F.M.; Perkins, A.V. Increased biological oxidation and reduced anti-oxidant enzyme activity in pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta 2005, 26, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czernichow, S.; Hercberg, S. Interventional studies concerning the role of antioxidant vitamins in cardiovascular diseases: A review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2001, 5, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, D.; Hedegaard, R.V.; Nielsen, J.H.; Skibsted, L.H. Oxidative stability of buttermilk as influenced by the fatty acid composition of cow’s milk manipulated by diet. J. Dairy Res. 2004, 71, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item, % of Dry Matter | Composition, % |

|---|---|

| Alfalfa hay | 13.80 |

| Corn silage | 36.86 |

| Distillers dried grains with solubles | 13.45 |

| Corn | 13.10 |

| Soybean meal | 9.33 |

| Whole cottonseeds | 3.80 |

| Steam-flaked corn | 4.10 |

| Sugar beet pulp | 3.90 |

| Calcium bicarbonate | 0.15 |

| Salt | 0.27 |

| Limestone | 0.45 |

| Dicarbonate | 0.36 |

| Magnesium oxide | 0.13 |

| Premix 1 | 0.30 |

| Chemical composition, % of dry matter | |

| Crude protein | 16.8 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 32.1 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 17.9 |

| Ca | 0.94 |

| P | 0.43 |

| Ash | 7.79 |

| NEL, Mcal/kg of DM | 1.68 |

| Items | Treatment 1 | Standard Error of Means | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid | Late | SD | Stage | SD × Stage | ||||

| LSD | HSD | LSD | HSD | |||||

| Milk yield, kg | ||||||||

| Milk | 36.3 | 36.1 | 27.9 | 28.5 | 0.38 | 0.66 | <0.01 | 0.34 |

| Fat | 1.29 | 1.27 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 0.023 | 0.96 | <0.01 | 0.84 |

| Protein | 1.05 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.016 | 0.75 | <0.01 | 0.56 |

| Lactose | 1.80 | 1.82 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 0.021 | 0.46 | <0.01 | 0.38 |

| Milk compositions, g/100 g | ||||||||

| Fat | 3.54 | 3.5 | 3.69 | 3.67 | 0.051 | 0.57 | <0.01 | 0.91 |

| Protein | 2.89 | 2.93 | 3.43 | 3.36 | 0.040 | 0.75 | <0.01 | 0.21 |

| Lactose | 4.97 | 4.98 | 5.03 | 5.07 | 0.048 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.52 |

| MUN, mg/dL 2 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 0.30 | 0.86 | 0.61 | 0.46 |

| BW 3 change, kg/cow | 16.1 | 16.8 | 23.8 | 22.4 | 2.62 | 0.82 | <0.01 | 0.54 |

| Items 1 | Treatment | Standard Error of Mean | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid | Late | SD | Stage | SD × Stage | ||||

| LSD | HSD | LSD | HSD | |||||

| Cortisol, ng/mL | 3.96 a | 5.24 b | 4.05 | 4.18 | 0.233 | <0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| NEFA, umol/L | 334 | 373 | 371 | 364 | 15.2 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.13 |

| BHBA, umol/L | 490 | 499 | 505 | 502 | 9.9 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.58 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 5.37 | 5.39 | 5.43 | 5.52 | 0.091 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.66 |

| SOD, U/mL | 106 | 109 | 103 | 101 | 1.95 | 0.85 | 0.16 | 0.81 |

| GSH-Px, U/mL | 117 | 120 | 115 | 117 | 2.53 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.76 |

| T-AOC, U/mL | 3.62 | 3.55 | 3.65 | 3.58 | 0.088 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.38 |

| MDA, mg/mL | 173 a | 194 b | 171 | 180 | 6.5 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Items 1 | Treatment | Standard Error of Mean | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid | Late | SD | Stage | SD × Stage | ||||

| LSD | HSD | LSD | HSD | |||||

| FA summary, g/100 g | ||||||||

| UFA | 32.5 b | 29.1 a | 30.9 | 30.7 | 0.60 | <0.01 | 0.91 | <0.01 |

| SFA | 67.5 a | 70.9 b | 69.1 | 69.3 | 0.54 | <0.01 | 0.92 | <0.01 |

| Selected individual FA | ||||||||

| C4:0 | 2.96 | 2.88 | 3.05 | 3.20 | 0.091 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.46 |

| C6:0 | 1.94 | 1.77 | 1.95 | 2.09 | 0.105 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.54 |

| C8:0 | 1.42 | 1.28 | 1.08 | 1.32 | 0.108 | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.35 |

| C10:0 | 3.30 | 3.23 | 3.38 | 3.31 | 0.044 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| C12:0 | 3.43 | 3.40 | 3.47 | 3.69 | 0.083 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| C14:0 | 11.5 a | 13.2 b | 12.2 | 11.6 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.05 |

| C14:1, cis-9 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 0.049 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.64 |

| C16:0 | 29.6 a | 31.4 b | 30.2 | 30.8 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| C16:1, cis-9 | 1.82 | 1.71 | 1.71 | 1.72 | 0.059 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.22 |

| C18:0 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.68 | 0.14 |

| C18:1, trans-9 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.061 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.22 |

| C18:1, trans-10 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.047 | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.61 |

| C18:1, trans-11 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.046 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.21 |

| C18:1, cis-9 | 20.8 b | 18.0 a | 19.6 | 19.2 | 0.51 | <0.01 | 0.89 | 0.02 |

| C18:1, cis-11 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.091 | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0.14 |

| C18:2, cis-9, cis-12 | 3.17 b | 2.74 a | 2.71 | 2.84 | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 0.04 |

| C18:2, cis-9, cis-12, cis-15 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.022 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| C18:2, trans-9, trans-11 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.045 | 0.87 | 0.37 | 0.48 |

| 18:2, trans-10, cis-12 | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.0051 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.39 |

| Items 1 | Treatment | Standard Error of Mean | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid | Late | SD | Stage | SD × Stage | ||||

| LSD | HSD | LSD | HSD | |||||

| SOD, U/mL | 4.47 a | 5.18 b | 4.74 | 4.62 | 0.207 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.04 |

| GSH-Px, U/mL | 411 a | 455 b | 435 | 432 | 8.2 | 0.02 | 0.90 | <0.01 |

| CAT, U/mL | 34.8 | 36.1 | 36.9 | 35.4 | 0.84 | 0.36 | 0.87 | 0.13 |

| T-AOC, U/mL | 1.44 a | 1.69 b | 1.56 | 1.56 | 0.064 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.05 |

| MDA, mg/mL | 1.41 b | 1.11 a | 1.27 | 1.24 | 0.071 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.04 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, D. Effects of Stocking Density on Milk Fatty Acids Composition and Oxidative Stability of Mid- and Late-Lactating Dairy Cows. Animals 2018, 8, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8090148

Lin S, Liu J, Wang K, Wang D. Effects of Stocking Density on Milk Fatty Acids Composition and Oxidative Stability of Mid- and Late-Lactating Dairy Cows. Animals. 2018; 8(9):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8090148

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Shixin, Jianxin Liu, Kaiying Wang, and Diming Wang. 2018. "Effects of Stocking Density on Milk Fatty Acids Composition and Oxidative Stability of Mid- and Late-Lactating Dairy Cows" Animals 8, no. 9: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8090148

APA StyleLin, S., Liu, J., Wang, K., & Wang, D. (2018). Effects of Stocking Density on Milk Fatty Acids Composition and Oxidative Stability of Mid- and Late-Lactating Dairy Cows. Animals, 8(9), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8090148