An Updated List of Generic Names in the Thoracosphaeraceae

Abstract

:1. Historical Survey

2. Taxonomy

3. Brief Summary of Methods

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elbrächter, M.; Gottschling, M.; Hildebrand-Habel, T.; Keupp, H.; Kohring, R.; Lewis, J.; Meier, K.J.S.; Montresor, M.; Streng, M.; Versteegh, G.J.M.; et al. Establishing an Agenda for Calcareous Dinoflagellate Research (Thoracosphaeraceae, Dinophyceae) including a nomenclatural synopsis of generic names. Taxon 2008, 57, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, K.J.S.; Young, J.R.; Kirsch, M.; Feist-Burkhardt, S. Evolution of different life-cycle strategies in oceanic calcareous dinoflagellates. Eur. J. Phycol. 2007, 42, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, A. Polythalamien des Seewerkalkes. In Die Urwelt der Schweiz; (in German). Heer, O.V., Ed.; Schultheß: Zurich, Switzerland, 1865; pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, T. Geologische Studien im Grenzgebiet zwischen helvetischer und ostalpiner Facies. II. Der südliche Rhaetikon. Ber. Naturf. Ges. Freiburg 1902, 12, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Deflandre, G. Micropaléontologie—Calciodinellum nov. gen., premier repésentant d’une famille nouvelle de dinoflagellés à thèque calcaire. Compt. Rend. Hebd. Séances Acad. Sci. 1947, 224, 1781–1782. (in French). [Google Scholar]

- Kamptner, E. Coccolithineen-Skelettreste aus Tiefseeablagerungen des Pazifischen Ozeans. Ann. Naturhistorischen Musums Wien 1963, 66, 139–204. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Bolli, H.M. Jurassic and Cretaceous Calcisphaerulidae from DSDP Leg 27, eastern Indian Ocean. Init. Rep. 1974, 27, 843–907. [Google Scholar]

- Pflaumann, U.; Krasheninnikov, V.A. Cretaceous calcisphaerulids from DSDP Leg 41, eastern North Atlantic. Init. Rep. 1978, 41, 817–839. [Google Scholar]

- Keupp, H. Die kalkigen Dinoflagellaten-Zysten der borealen Unter-Kreide (Unter-Hauterivium bis Unter-Albium). Facies 1981, 5, 1–189. (in German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janofske, D. Kalkiges Nannoplankton, insbesondere Kalkige Dinoflagellaten-Zysten der alpinen Ober-Trias: Taxonomie, Biostratigraphie und Bedeutung für die Phylogenie der Peridiniales. Berliner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen 1992, 4, 1–53. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Willems, H. Kalkige Dinoflagellaten-Zysten aus der oberkretazischen Schreibkreide-Fazies N-Deutschlands (Coniac bis Maastricht). Senckenbergiana Lethaea 1988, 68, 433–477. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Versteegh, G.J.M. New Pliocene and Pleistocene calcareous dinoflagellate cysts from southern Italy and Crete. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1993, 78, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohring, R. Kalkdinoflagellaten aus dem Mittel- und Obereozän von Jütland (Dänemark) und dem Pariser Becken (Frankreich) im Vergleich mit anderen Tertiär-Vorkommen. Berliner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen 1993, 6, 1–164. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Kienel, U. Die Entwicklung der kalkigen Nannofossilien und der kalkigen Dinoflagellaten-Zysten an der Kreide/Tertiär-Grenze in Westbrandenburg im Vergleich mit Profilen in Nordjütland und Seeland (Dänemark). Berliner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen 1994, 12, 1–87. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand-Habel, T. Die Entwicklung kalkiger Dinoflagellaten im Südatlantik seit der höheren Oberkreide. Berichte Fachbereich Geowissenschaften Universität Bremen 2002, 192, 1–152. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Zügel, P. Verbreitung kalkiger Dinoflagellaten-Zysten im Cenomen/Turon von Westfrankreich und Norddeutschland. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 1994, 176, 1–120. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Streng, M. Phylogenetic aspects and taxonomy of calcareous dinoflagellates. Berichte Fachbereich Geowissenschaften Universität Bremen 2003, 210, 1–157. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, K.J.S. Calcareous dinoflagellates from the Mediterranean Sea: Taxonomy, ecology and palaeoenvironmental application. Berichte Fachbereich Geowissenschaften Universität Bremen 2003, 206, 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, D.; Dale, B. Quaternary calcareous dinoflagellates (Calciodinellideae) and their natural affinities. J. Paleontol. 1968, 42, 1395–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. Cyst-theca relationships in Scrippsiella (Dinophyceae) and related orthoperidinoid genera. Bot. Mar. 1991, 34, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Montresor, M.; Janofske, D.; Willems, H. The cyst-theca relationship in Calciodinellum operosum emend. (Peridiniales, Dinophyceae) and a new approach for the study of calcareous cysts. J. Phycol. 1997, 33, 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Montresor, M.; Zingone, A.; Marino, D. The calcareous resting cyst of Pentapharsodinium tyrrhenicum comb. nov. (Dinophyceae). J. Phycol. 1993, 29, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio, G.; Marino, D.; Bianco, L.; Busico, E.; Montresor, M. Toward an assessment on the taxonomy of dinoflagellates that produce calcareous cysts (Calciodinelloideae, Dinophyceae): A morphological and molecular approach. J. Phycol. 1999, 35, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Karwath, B. Ecological studies on living and fossil calcareous dinoflagellates of the equatorial and tropical Atlantic Ocean. Berichte Fachbereich Geowissenschaften Universität Bremen 2000, 152, 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, K.J.S.; Janofske, D.; Willems, H. New calcareous dinoflagellates (Calciodinelloideae) from the Mediterranean Sea. J. Phycol. 2002, 38, 602–615. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling, M.; Knop, R.; Plötner, J.; Kirsch, M.; Willems, H.; Keupp, H. A molecular phylogeny of Scrippsiella sensu lato (Calciodinellaceae, Dinophyta) with interpretations on morphology and distribution. Eur. J. Phycol. 2005, 40, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinssmeister, C.; Soehner, S.; Kirsch, M.; Facher, E.; Meier, K.J.S.; Keupp, H.; Gottschling, M. Same but different: Two novel bicarinate species of extant calcareous dinophytes (Thoracosphaeraceae, Peridiniales) from the Mediterranean Sea. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Kirsch, M.; Zinssmeister, C.; Soehner, S.; Meier, K.J.; Liu, T.; Gottschling, M. Waking the dead: Morphological and molecular characterization of extant †Posoniella tricarinelloides (Thoracosphaeraceae, Dinophyceae). Protist 2013, 164, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, H. Die Bevölkerung des Ozeans mit Plankton. Nach den Ergebnissen der Zentrifugenfänge während der Ausreise der “Deutschland” 1911. Zugleich ein Beitrag zur Biologie des Atlantischen Ozeans. Arch. Biontologie 1920, 4, 1–617. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Fütterer, D.K. Kalkige Dinoflagellaten (“Calciodinelloideae”) und die systematische Stellung der Thoracosphaeroideae. Neues Jahrbuch Geologie Paläontologie Abhandlungen 1976, 151, 119–141. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Inouye, I.; Pienaar, R.N. Observations on the life cycle and microanatomy of Thoracosphaera heimii (Dinophyceae) with special reference to its systematic position. S. Afr. J. Bot. 1983, 2, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tangen, K.; Brand, L.E.; Blackwelder, P.L.; Guillard, R.R.L. Thoracosphaera heimii (Lohmann) Kamptner is a dinophyte: Observations on its morphology and life cycle. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1982, 7, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensome, R.A.; Taylor, F.J.R.; Norris, G.; Sarjeant, W.A.S.; Wharton, D.I.; Williams, G.L. A Classification of Living and Fossil Dinoflagellates. In Micropaleontology; Special Publication 7; American Museum of Natural History: : New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 1–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling, M.; Keupp, H.; Plötner, J.; Knop, R.; Willems, H.; Kirsch, M. Phylogeny of calcareous dinoflagellates as inferred from ITS and ribosomal sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2005, 36, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D.; Dale, B. Modern dinoflagellate cysts and evolution of the Peridiniales. Micropaleontology 1968, 14, 265–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, A.R.; Saito, K.; Deeds, J.R.; Robledo, J.A.F.; Vasta, G.R. A Decade of Research on Pfiesteria spp. and Their Toxins: Unresolved Questions and an Alternative Hypothesis. In Seafood and Freshwater Toxins: Pharmacology, Physiology, and Detection, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 717–751. [Google Scholar]

- Steidinger, K.A.; Burkholder, J.M.; Glasgow, H.B., Jr; Hobbs, C.W.; Garrett, J.K.; Truby, E.W.; Noga, E.J.; Smith, S.A. Pfiesteria piscicida gen. et sp. nov. (Pfiesteriaceae fam. nov.), a new toxic dinoflagellate with a complex life cycle and behavior. J. Phycol. 1996, 32, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

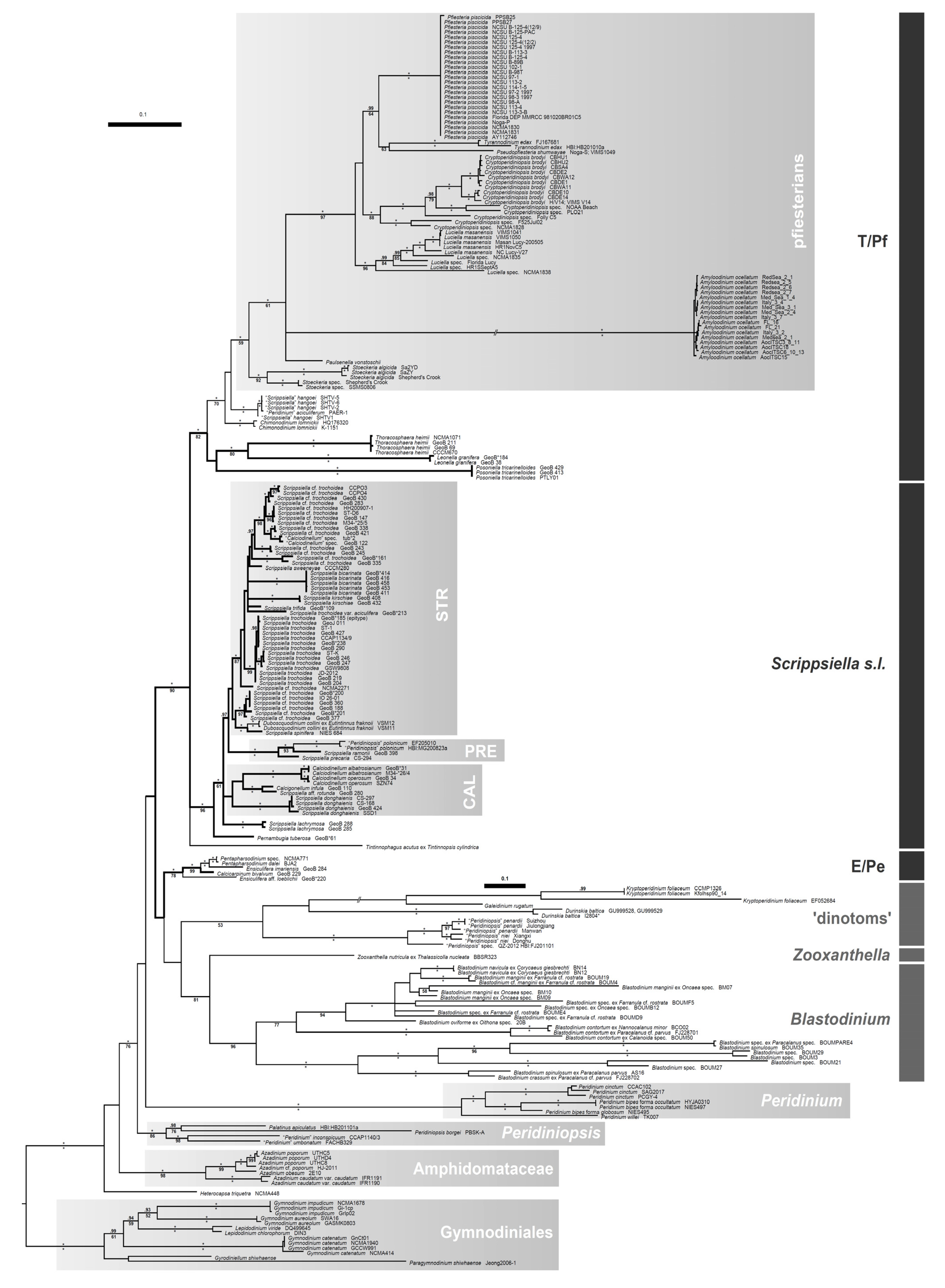

- Gottschling, M.; Soehner, S.; Zinssmeister, C.; John, U.; Plötner, J.; Schweikert, M.; Aligizaki, K.; Elbrächter, M. Delimitation of the Thoracosphaeraceae (Dinophyceae), including the calcareous dinoflagellates, based on large amounts of ribosomal RNA sequence data. Protist 2012, 163, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bhattacharya, D.; Lin, S.J. A three-gene dinoflagellate phylogeny suggests monophyly of Prorocentrales and a basal position for Amphidinium and Heterocapsa. J. Mol. Evol. 2007, 65, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, U.; Salas, R.; Gottschling, M.; Krock, B.; O’Driscol, D.; Elbrächter, M. Amphidoma languida sp. nov. (Dinophyceae) reveals a close relationship between Amphidoma and Azadinium. Protist 2012, 163, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidinger, K.A.; Landsberg, J.H.; Mason, P.L.; Vogelbein, W.K.; Tester, P.A.; Litaker, R.W. Cryptoperidiniopsis brodyi gen. et sp. nov. (Dinophyceae), a small lightly armored dinoflagellate in the Pfiesteriaceae. J. Phycol. 2006, 42, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.L.; Litaker, R.W.; Jeong, H.J.; Ha, J.H.; Reece, K.S.; Stokes, N.A.; Park, J.Y.; Steidinger, K.A.; Vandersea, M.W.; Kibler, S.; Tester, P.A.; Vogelbein, W.K. Description of a new genus of Pfesteria-like dinoflagellate, Luciella gen. nov. (Dinophyceae), including two new species: Luciella masanensis sp. nov. and Luciella atlantis sp. nov. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, A.J. On the identity of the freshwater dinoflagellate Glenodinium edax, with a discussion on the genera Tyrannodinium and Katodinium, and the description of Opisthoaulax gen. nov. Phycologia 2011, 50, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.F.; Andersen, R.A.; Jameson, I.; Kuepper, F.C.; Coffroth, M.-A.; Vaulot, D.; le Gall, F.; Veron, B.; Brand, J.J.; Skelton, H.; et al. Evaluating the ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) as a candidate dinoflagellate barcode marker. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, D.W.; Kim, S.; Bachvaroff, T.R.; Handy, S.M.; Delwiche, C.F. Tintinnophagus acutus n. g., n. sp. (Phylum Dinoflagellata), an ectoparasite of the ciliate Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday 1887, and its relationship to Duboscquodinium collini Grassé 1952. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2010, 57, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.D.; Dodson, M.; Santos, S.; Gast, R.; Rogerson, A.; Sullivan, B.; Moss, A.G. Pentapharsodinium tyrrhenicum is a parasitic dinoflagellate of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.D. A Parasitic Dinoflagellate of the Ctenophore Mnemiopsis sp. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Montresor, M.; Sgrosso, S.; Procaccini, G.; Kooistra, W.H.C.F. Intraspecific diversity in Scrippsiella trochoidea (Dinophyceae): Evidence for cryptic species. Phycologia 2003, 42, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soehner, S.; Zinssmeister, C.; Kirsch, M.; Gottschling, M. Who am I—And if so, how many? Species diversity of calcareous dinophytes (Thoracosphaeraceae, Peridiniales) in the Mediterranean Sea. Org. Divers. Evol. 2012, 12, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschling, M.; McLean, T.I. New home for tiny symbionts: Dinophytes determined as Zooxanthella are Peridiniales and distantly related to Symbiodinium. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 67, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, A.; Massana, R.; Saiz, E. Parasitic species of the genus Blastodinium (Blastodiniphyceae) are peridinioid dinoflagellates. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, D.W.; Bachvaroff, T.; Handy, S.M.; Kim, S.; Gárate-Lizárraga, I.; Delwiche, C.F. Prevalence and phylogeny of parasitic dinoflagellates (genus Blastodinium) infecting copepods in the Gulf of California. CICIMAR Oceánides 2008, 23, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, M.; Shimada, S.; Horiguchi, T. Galeidiniium rugatum gen. et sp. nov. (Dinophyceae), a new coccoid dinoflagellate with a diatom endosymbiont. J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, T.; Takano, Y. Serial replacement of a diatom endosymbiont in the marine dinoflagellate Peridinium quinquecorne (Peridiniales, Dinophyceae). Phycol. Res. 2006, 54, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, G.X.; Hu, Z.-Y. Durinskia baltica (Dinophyceae), a newly recorded species and genus from China, and its systematics. J. Syst. Evol. 2011, 49, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ride, W.D.L.; Cogger, H.G.; Dupuis, C.; Krauss, O.; Minelli, A.; Thompson, F.C.; Tubbs, P.K. International code of zoological nomenclature: Adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences; International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Buck, W.R.; Demoulin, V.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Marhold, K.; Prado, J.; et al. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011; Koeltz: Königstein, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Litaker, R.W.; Tester, P.A.; Colorni, A.; Levy, M.G.; Noga, E.J. The phylogenetic relationship of Pfiesteria piscicida, cryptoperidiniopsoid sp. Amyloodinoum ocellatum and a Pfiesteria-like dinoflagellate to other dinoflagellates and apicomplexans. J. Phycol. 1999, 35, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.F.; Medlin, L.K. The systematic position of the parasitoid marine dinoflagellate Paulsenella vonstoschii (Dinophyceae) inferred from nuclear-encoded small subunit ribosomal DNA. Protist 2005, 156, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, I.; Lee, S.H.; Ha, J.H.; Yih, W.H. Stoeckeria algicida n. gen., n. sp. (Dinophyceae) from the coastal waters off southern Korea: Morphology and small subunit ribosomal DNA gene sequence. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2005, 52, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasová, M.; Kopčáková, J.; Reháková, D. Bádenské asociácie vápnitých dinoflagelát z vrtu Stupava HGP-3 a Malacky-101 (viedenská panva). Mineralia Slovaca 2007, 39, 107–122. (in Slovak). [Google Scholar]

- Calado, A.J.; Craveiro, S.C.; Daugbjerg, N.; Moestrup, Ø. Description of Tyrannodinium gen. nov., a freshwater dinoflagellate closely related to the marine Pfiesteria-like species. J. Phycol. 2009, 45, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdikmen, H. Substitute names for some unicellular animal taxa (Protozoa). Munis Entomol. Zool. 2009, 4, 233–256. [Google Scholar]

- Streng, M.; Banasová, M.; Reháková, D.; Willems, H. An exceptional flora of calcareous dinoflagellates from the middle Miocene of the Vienna Basin, SW Slovakia. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2009, 153, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, S.C.; Calado, A.J.; Daugbjerg, N.; Hansen, G.; Moestrup, Ø. Ultrastructure and LSU rDNA-based phylogeny of Peridinium lomnickii and description of Chimonodinium gen. nov. (Dinophyceae). Protist 2011, 162, 590–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, S.C.; Pandeirada, M.S.; Daugbjerg, N.; Moestrup, Ø.; Calado, A.J. Ultrastructure and phylogeny of Theleodinium calcisporum gen. et sp. nov., a freshwater dinoflagellate that produces calcareous cysts. Phycologia 2013, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatton, É.; Grassé, P.-P. Classe des Dinoflagelles ou Péridiniens. In Phylogénie. Protozoaires: Généralités. Flagellés 1; (in French). Grassé, P.-P., Ed.; Masson: Paris, France, 1952; pp. 309–406. [Google Scholar]

- Balech, E. Two new genera of dinoflagellates from California. Biol. Bull. 1959, 116, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeblich, A.R. Dinoflagellate nomenclature. Taxon 1965, 14, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, J.E.; Bown, P. Exceptionally well-preserved Cretaceous microfossils reveal new biomineralization styles. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2052. [Google Scholar]

- Bourrelly, P. Notes sur les péridiniens d’eau douce. Protistologica 1968, 4, 5–13. (in French). [Google Scholar]

- Pascher, A. Über die Beziehungen der Cryptomonaden zu den Algen. Berichte Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft 1911, 29, 193–203. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Blank, R.J.; Trench, R.K. Nomenclature of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates. Taxon 1986, 35, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, A.T.; Iglesias-Prieto, R.; Trench, R.K. Scrippsiella velellae sp. nov. (Peridiniales) and Gloeodinium viscum sp. nov. (Phytodiniales), dinoflagellate symbionts of two hydrozoans (Cnidaria). J. Phycol. 1993, 29, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.C. Report of the Committee for Algae: 2. Taxon 1994, 43, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebs, G.A. Flagellatenstudien. Zeitschrift Wissenschaftliche Zoologie 1892, 5, 265–445. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Loeblich, A.R. The Amphiesma or Dinoflagellate Cell Covering. In Proceedings of the North American Paleontological Convention 2; Yochelson, E.L., Ed.; Allen Press: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1971; pp. 867–929. [Google Scholar]

- Cavers, F. Recent work on flagellata and primitive algæ. New Phytol. 1913, 12, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J. Coccolithineae. In Dr. L. Rabenhorst’s Kryptogamen-Flora 10, Abt. 2; (in German). Kolkwitz, R., Ed.; Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft: Leipzig, Germany, 1930; pp. 89–273. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 2688–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Gottschling, M.; Soehner, S. An Updated List of Generic Names in the Thoracosphaeraceae. Microorganisms 2013, 1, 122-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms1010122

Gottschling M, Soehner S. An Updated List of Generic Names in the Thoracosphaeraceae. Microorganisms. 2013; 1(1):122-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms1010122

Chicago/Turabian StyleGottschling, Marc, and Sylvia Soehner. 2013. "An Updated List of Generic Names in the Thoracosphaeraceae" Microorganisms 1, no. 1: 122-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms1010122

APA StyleGottschling, M., & Soehner, S. (2013). An Updated List of Generic Names in the Thoracosphaeraceae. Microorganisms, 1(1), 122-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms1010122