Sending a Dear John Letter: Public Information Campaigns and the Movement to “End Demand” for Prostitution in Atlanta, GA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Prostitution Policy Narratives & PICs

3. Materials & Methods

4. Results & Discussion

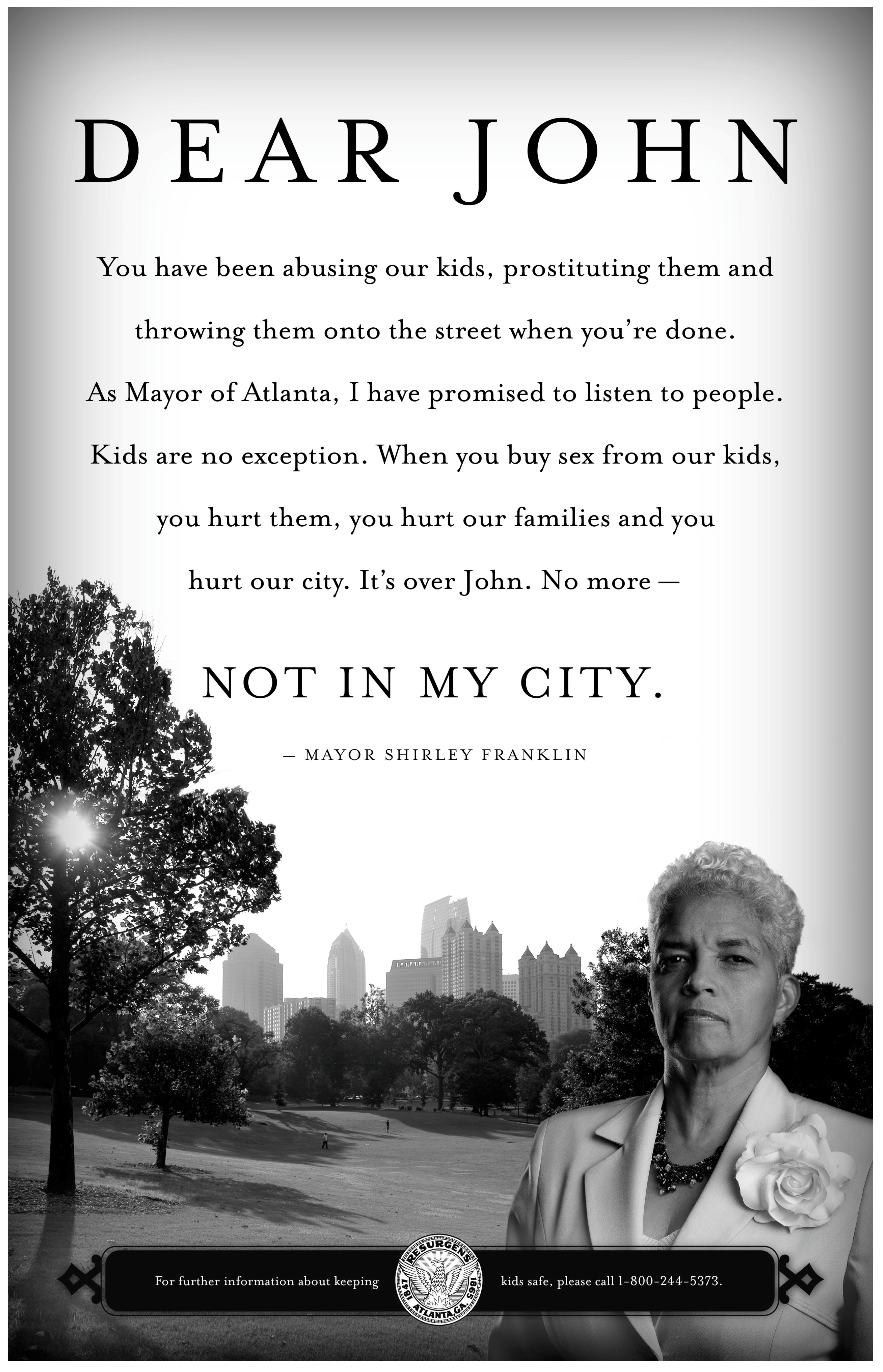

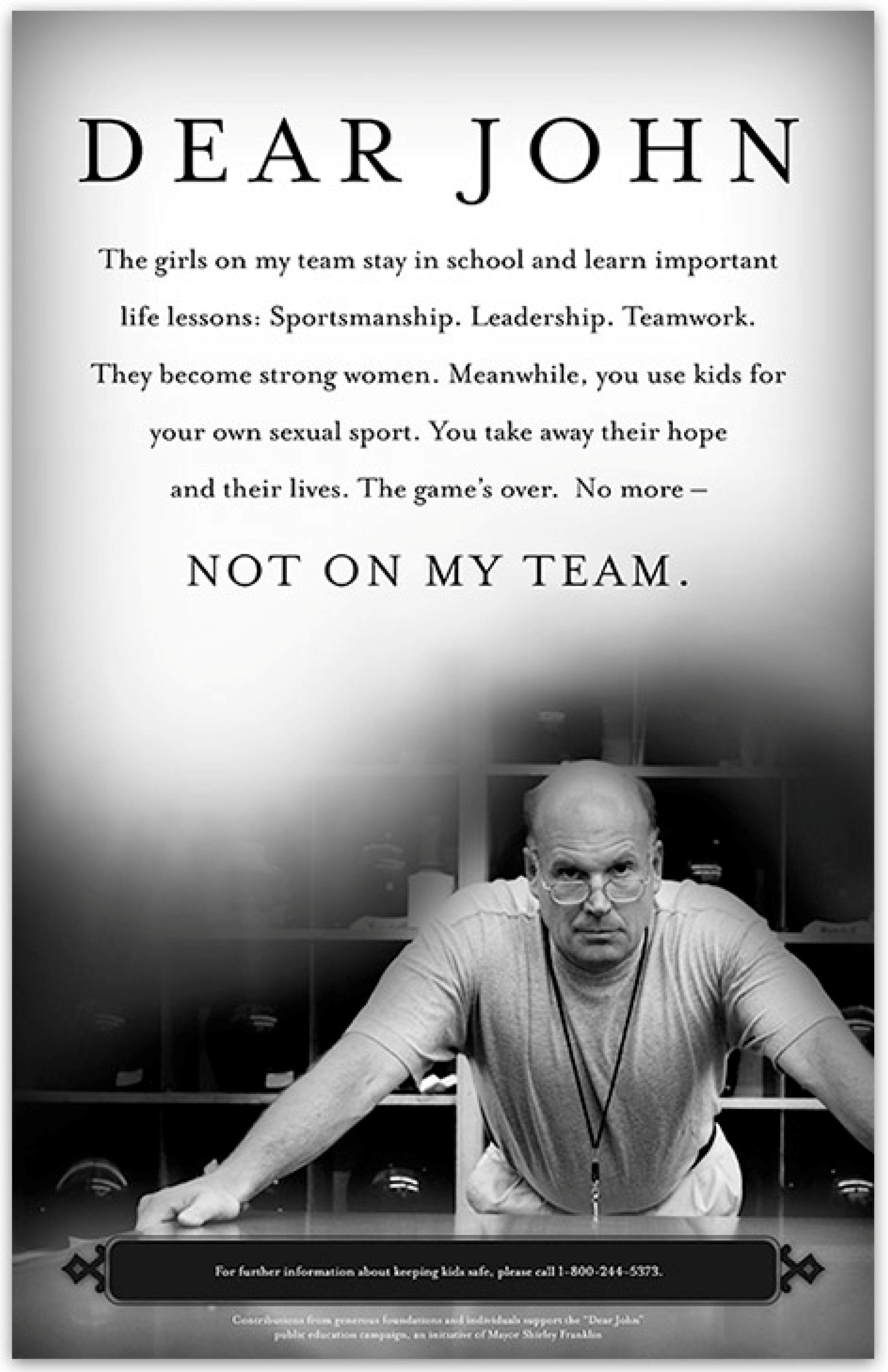

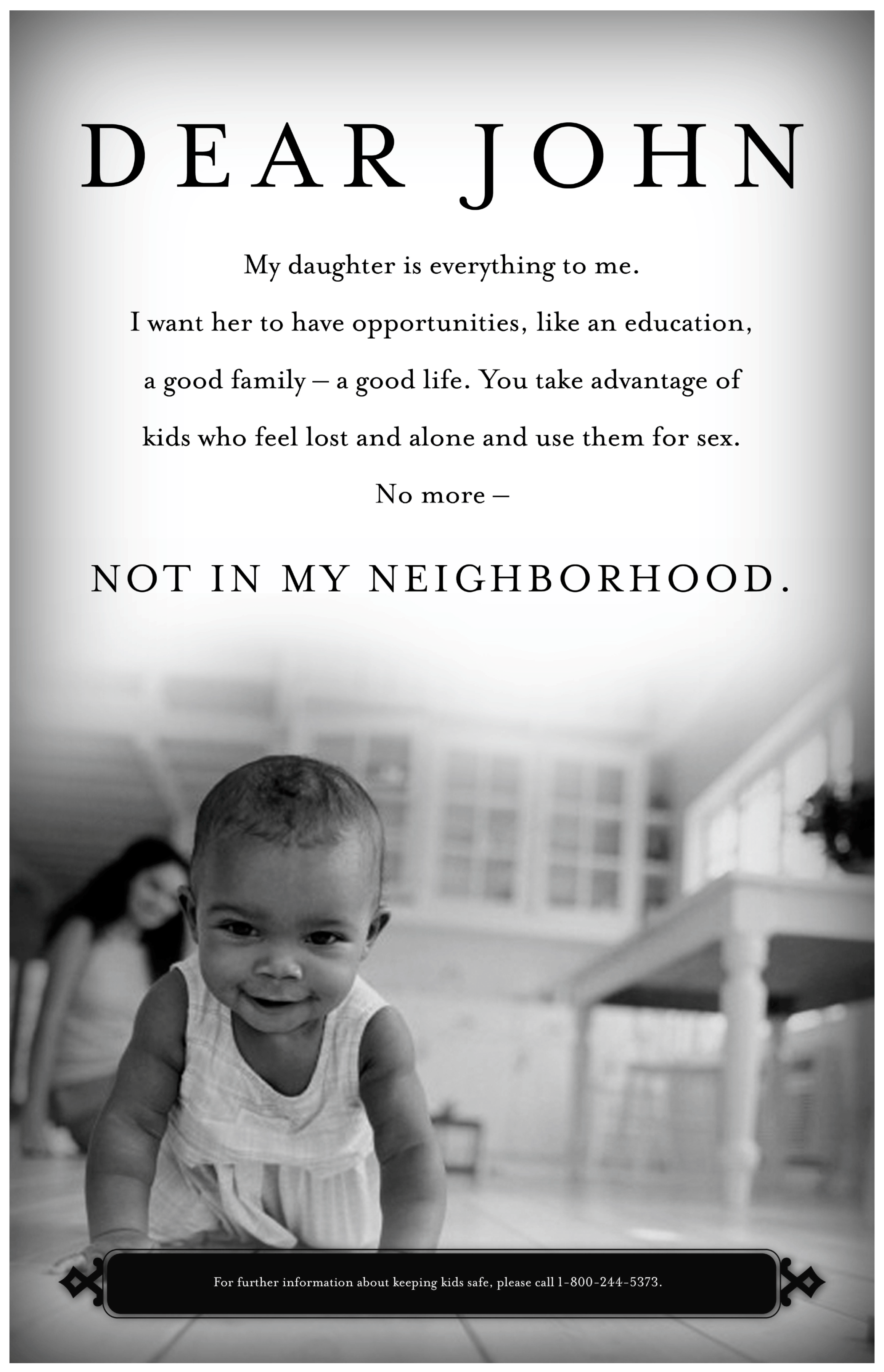

4.1. The Male Demand Narrative in Atlanta & Dear John

Yes, there was legislative resistance. Some legislators said that we already had laws (for statutory rape, etc.) that would cover this issue, but the DAs [district attorneys] were not using them because these are hard cases to make. Many girls don’t see themselves as victims because of their relationship with their pimps, so it is hard to get them to testify. Also, these girls often run away—their defenses are high and they are not easy children to deal with. Many [legislators] see [the girls] as “asking for it”. Also, some legislators just said that prostitution will always be with us(Interview, Nina Hickson, 6 January 2014).

4.2. Dear John: Telling a Story

4.2.1. Victims

4.2.2. Villains

4.2.3. Solutions

4.2.4. Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abt Associates & National Institutes of Justice. 2014. Tally of US Cities and Counties throughout May 2014. Available online: http://www.demandforum.net/tactics/ (accessed on 19 September 2015).

- Andrijasevic, Rutvica. 2007. Beautiful Dead Bodies: Gender, migration and representation in anti-trafficking campaigns. Feminist Review 86: 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijasevic, Rutvica, and Nicola Mai. 2016. Trafficking (in) Representations: Understanding the recurring appeal of victimhood and slavery in neoliberal times. Anti-Trafficking Review 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, Carol Lee. 2009. Analysing Policy: What's the Problem Represented to Be? Frenchs Forest: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Carrie. 2014. An Intersectional Analysis of Sex Trafficking Films. Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 12: 208–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Carrie N. 2015. An Examination of Some Central Debates on Sex Trafficking in Research and Public Policy in the United States. Journal of Human Trafficking 1: 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, Michael G. W., and Molly Andrews. 2004. Considering Counter Narratives: Narrating, Resisting, Making Sense, Studies in Narrative. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Elizabeth. 2010. Militarized Humanitarianism Meets Carceral Feminism: The Politics of Sex, Rights, and Freedom in Contemporary Antitrafficking Campaigns. Signs 36: 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, Joel. 2017. Social Problems, 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Joel, and Scott R. Harris. 2012. Making Sense of Social Problems: New Images, New Issues, Social Problems, Social Constructions. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, Christina. 2011. Migration Control and Narratives of Steering. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 13: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, Chistina, Andrew Geddes, and Peter Scholten. 2011. The Role of Narratives in Migration Policy-Making: A Research Framework. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 13: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, Anne, Terry Lilley, and Chrysanthi Leon. 2016. Reform or Remand? Race, Nativity, and the Immigrant Family in the History of Prostitution. Studies in Law, Politics and Society 71: 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Boxill, Nancy A., and Deborah J. Richardson. 2007. Ending Sex Trafficking of Children in Atlanta. Affilia 22: 138–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucken-Knapp, Gregg, Johan Karlsson Schaffer, and Pia Levin. 2014. Comrades, Push the Red Button! Prohibiting the purchase of sexual services in Sweden but not in Finland. In Negotiating Sex Work : Unintended Consequences of Policy and Activism. Edited by Carisa Renae Showden and Samantha Majic. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cojucaru, Claudia. 2015. Sex trafficking, captivity, and narrative: Constructing victimhood with the goal of salvation. Dialectical Anthropology 39: 183–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowhurst, Isabel, Joyce Outshoorn, and May-Len Skilbrei. 2012. Introduction: Prostitution Policies in Europe. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 9: 187–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Emilio, John, and Estelle Freedman. 1997. Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, James Price, and Eugenia Peck. 2000. Affect and Persuasion: Emotional Responses to Public Service Announcements. Communication Research 27: 461–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditmore, Melissa, Anna Maternick, and Katherine Zapert. 2012. The Road North: The rol of Gender, Poverty and Violence in Trafficking from Mexico to the US. New York: Sex Workers Project. [Google Scholar]

- Dobash, Emerson, and Russell Dobash. 2000. The politics and policies of responding to violence against women. In Home Truths About Domestic Violence: Feminist Influences on Policy and Practice. Edited by Jalna Hanmer. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Doezema, Jo. 2010. Sex Slaves and Discourse Masters: The Construction of Trafficking. London and New York: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, Brian. 2006. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-Vice Activism, 1887–1917. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman & Associates. 2008. Dear John: Ending Child Prostitution in Atlanta. Atlanta: Edelman & Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Emmison, Michael, Philip Smith, and Margery Mayall. 2012. Researching the Visual, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Rebecca, Jamilia Blake, and Thalia Gonzalez. 2017. Girl Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood. Washington: Center on Poverty and Inequality. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank. 2003. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, Charles, and Karyn Lacy. 2003. The Changing Face of Atlanta. Footnotes. Available online: http://www.asanet.org/footnotes/jan03/indextwo.html (accessed on 9 November 2017).

- Gira Grant, Melissa. 2014. Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, Erich, and Noah Ben-Yehuda. 1994. Moral panics: Culture, politics, and social construction. Annual Review of Sociology 20: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2007. When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm. Perspectives on Politics 5: 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Jane O. 2001. World Of Pimps Is Sordid, Scary, but Is It Racketeering? Special Report: Selling Atlanta’s Children. Atlanta Journal Constitution, April 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Jane O. 2002. Judge throws the book at pimps; “Sir Charles” gets 30 years, “Batman,” 40. Atlanta Journal Constitution, July 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hickson, Nina. 2000. An Epidemic of Tragic Proportions. Atlanta Journal Constitution, June 11. [Google Scholar]

- Horning, Amber, and Anthony Marcus. 2017. Introduction: In Search of Pimps and Other Varieties. In Third Party Sex Work and Pimps in the Age of Anti-Trafficking. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, Carolyn, Mary Bosworth, and Michelle Dempsey. 2011. Labelling the Victims of Sex Trafficking: Exploring the Borderland between Rhetoric and Reality. Social & Legal Studies 20: 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Ronald N., and Sarah Sobieraj. 2007. Narrative and Legitimacy: U.S. Congressional Debates about the Nonprofit Sector. Sociological Theory 25: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Michael, and Mark McBeth. 2010. A Narrative Policy Framework: Clear Enough to be Wrong. Policy Studies Journal 38: 329–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempadoo, Kamala. 2015. The Modern-Day White (Wo)Man’s Burden: Trends in Anti-Trafficking and Anti-Slavery Campaigns. Journal of Human Trafficking 1: 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimm, Susanne, and Birgit Sauer. 2010. Discourses on forced prostitution, trafficking in women, and football: A comparison of anti-trafficking campaigns during the World Cup 2006 and the European Championship 2008. Soccer & Society 11: 815–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, John. 1995. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, 2nd ed. New York: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, Michelle. 2007. Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: Articulating a feminist discursive practice. Critical Discourse Studies 4: 141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutnick, Alexandra. 2016. Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Beyond Victims and Villains. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Anthony, Amber Horning, Ric Curtis, Jo Sanson, and Efram Thompson. 2014. Conflict and Agency among Sex Workers and Pimps: A Closer Look at Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 653: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, Willoughby. 2012. Faulty figures mask trafficking reallity. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 30. [Google Scholar]

- Matheson, Catherine M., and Rebecca Finkel. 2013. Sex trafficking and the Vancouver Winter Olympic Games: Perceptions and preventative measures. Tourism Management 36: 613–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, Mark K., Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Paul L. Hathaway, Linda E. Tigert, and Lynette J. Sampson. 2010. Buffalo tales: Interest group policy stories in Greater Yellowstone. Policy Sciences 43: 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musto, Jennifer. 2016. Control and Protect: Collaboration, Carceral Protection, and Domestic Sex Trafficking in the United States. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Erin. 2013. Ideal Victims in Trafficking Awareness Campaigns. In Crime, Justice and Social Democracy: International Perspectives. Edited by Kerry Carrington, Matthew Ball, Erin O’Brien and Juan Marcellus Tauri. Houndmills, Basingstoke and Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 315–26. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Erin. 2015. Human Trafficking Heroes and Villains: Representing the Problem in Anti-Trafficking Awareness Campaigns. Social & Legal Studies 25: 205–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ocen, Priscilla. 2015. (E)racing Childhood: Examining the Racialized Construction of Childhood and Innocence in the Treatment of Sexually Exploited Minors. UCLA Law Review 62: 1586–640. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Kimala. 2011. The Quest for Purity: The Role of Policy Narratives in Determining Teen Girls’ Access to Emergency Contraception in the USA. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 8: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priebe, Alexandra, and Cristen Suhr. 2005. Hidden in Plain View: The Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Girls in Atlanta. Atlanta: Atlanta Women’s Agenda. [Google Scholar]

- Queen, Carol. 1997. Real Live Nude Girl: Chronicles of Sex-Positive Culture, 1st ed. Pittsburgh: Cleis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raible, John. 2011. Queering the Adult Gaze: Young Male Hustlers and Their Alliances with Older Gay Men. Journal of LGBT Youth 8: 260–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Amy Cabrera. 2011. Contraception as Health? The Framing of Issue Categories in Contemporary Policy Making. Administration & Society 43: 930–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 3rd ed. London and Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Ruth. 1982. The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900–1918. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, Paul A., and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith. 1993. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach, Theoretical Lenses on Public Policy. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schloenhardt, Andreas, Paris Astill-Torchia, and Jarrod Jolly. 2012. Be Careful What You Pay For: Awareness Raising on Trafficking in Persons. Washington University Global Studies Law Review 11: 415–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Anne L., and Helen M. Ingram. 2005. Deserving and Entitled: Social Constructions and Public Policy, SUNY Series in Public Policy. Albany: State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, Rachel. 2015. Somone you know is a sex worker. In Queer Sex Work. Edited by Mary Whowell Laing. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 253–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Shea, Peregrine, and Dvora Yanow. 2012. Interpretive Research Design: Concepts and Processes, Routledge Series on Interpretive Methods. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, Elizabeth, Michael Jones, Mark McBeth, and Ross Lane. 2013. An Angel on the Wind: How Heroic Policy Narratives Shape Policy Realities. Policy Studies Journal 41: 453–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhav, Shaul. 2005. Thin and thick narrative analysis: On the question of defining and analyzing political narratives. Narrative Inquiry 15: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, Michael, Karen McLaughlin, Rachel Durchslag, Hugh McDonough, Dana Hunt, Kristina Kliorys, Caroline Nobo, Lauren Olsho, Stephanie Davis, Sara Collins, and et al. 2010. Developing a National Action Plan for Eliminating Sex Trafficking. Cambridge: Abt Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Shively, Michael, Kristina Kliorys, Kristin Wheeler, and Dana Hunt. 2012. An Overview of Anti-Demand Public Education in the United States. Washington: Abt Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Showden, Carisa Renae, and Samantha Majic. 2018. Forthcoming. Youth Who Trade Sex in the US: Intersectionality, Agency, and Vulnerability. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sidney, Mara. 2005. Contested Images of Race and Place: The politics of housing discrimination. In Deserving and Entitled: Social Constructions and Public Policy. Edited by Ann Schneider and Helen Ingram. Albany: State University of New York, pp. 111–38. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund, Gretchen. 2005. Running from the Rescuers: New US Crusades Against Sex Trafficking and the Rhetoric of Abolition. NWSA Journal 17: 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, Sarah. 2010. ‘Combating the Scourge’: Constructing the Masculine ‘Other’ through U.S. Government Anti-trafficking Campaigns. Journal of Hate Studies 9: 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Deborah A. 2002. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Carol A. B., and Tracy X. Karner. 2015. Discovering Qualitative Methods: Ethnography, Interviews, Documents, and Images, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Janet, and Mary Tschirhart. 1994. Public information campaigs as policy instruments. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 13: 82–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzer, Ronald. 2015. Human Trafficking and Contemporary Slavery. Annual Review of Sociology 41: 223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, Mark. 1995. The Legislative Impact of Social Movement Organizations: The Anti-Drunken-Driving Movement and the 21-Year-Old Drinking Age. Social Science Quarterly 76: 311–27. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Iris. 2003. The Logic of Masculinist Protection: Reflections on the Current Security State. Signs 29: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | To avoid conflating voluntary and coerced sex work and stigmatizing those involved in these activities, a note on terms is important. I use “sex work” in reference to a range of legal and illegal sexual activities that are voluntarily exchanged for cash or other trade, and I use “prostitution” in reference to the specific form of sex work that is criminalized in the majority of the US. I use “sex trafficking” and/or “commercial sexual exploitation” (CSE, the term used by advocates in Atlanta) to describe a commercial sex act induced by force, fraud, or coercion. I refer to persons who engage in these activities as sex workers or “person who trade sex”, and minors (persons under 18) as “young people who trade sex”. I refer to “girls and young women” when specifying the gendered population of minors that is the target of Dear John. Additionally, following Marcus et al. (2014), I use “purchasers” in reference to those who purchase sexual services, and “facilitators” regarding third parties who procure commercial sexual services (to avoid the more derogatory terms “johns” and “pimps”, respectively). When quoting individuals directly, however, I provide their terms for the activities/persons they describe. |

| 2 | Notable examples include Melissa Farley, Kathleen Barry, Donna Hughes, and Sheila Jeffreys. |

| 3 | The majority of U.S. states criminalize prostitution to some degree, with the exception of eleven Nevada counties where prostitution is currently legal in brothels. Additionally, state and federal laws that target organized crime (e.g., prohibiting racketeering), kidnapping, and rape may also be used to target persons who facilitate commercial sex. Federal laws that address sex trafficking specifically emerged with the passage of the Mann Act, noted previously, and through treaties such as the International Agreement for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic, the first in a series of anti-human trafficking treaties that were initially negotiated in Paris in 1904. More recently, in response to advocates’ and policymakers concerns about sex trafficking, Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000. By 2013, all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and all but one U.S. territory enacted TVPA-like laws, and in 2015, the bipartisan Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act (JVTA) augmented the TVPA by increasing penalties for the trafficking of minors. |

| 4 | This video is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fRsbo6g21hU. |

| 5 | Since all of these interviews were conducted with adults (persons over the age of 18), many of whom were public figures, my University’s Human Research Protection Program determined the project was one that posed “minimal risk” to participants. No unanticipated ethical or other problems arose during the course of my research interviews. |

| 6 | Prior to Dear John, prostitution and related crimes such as pimping and pandering (so labeled) were and are predominantly criminalized under Title 16: Chapter 6 (Crimes and Offenses: Sexual Offenses) of Georgia’s state code. And regarding sex trafficking, in 2001, Georgia passed the Child Sexual Commerce Protection Act, which criminalized the purchase of sexual services from minors and specified that minors could not be charged with prostitution. As well, Section 106 of Atlanta’s Code of Ordinances further prohibits engaging in and profiting from prostitution. |

| 7 | This claim is sustained by state prostitution arrest statistics provided by Cheryl Payton ([email protected]), a program manager with the Georgia Crime Information Center (email correspondence, 6 April 2017). |

| 8 | Only Hickson and Davis were available for interviews. |

| 9 | Georgia Arrest statistics (see note 7). |

| 10 |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majic, S. Sending a Dear John Letter: Public Information Campaigns and the Movement to “End Demand” for Prostitution in Atlanta, GA. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040138

Majic S. Sending a Dear John Letter: Public Information Campaigns and the Movement to “End Demand” for Prostitution in Atlanta, GA. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(4):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040138

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajic, Samantha. 2017. "Sending a Dear John Letter: Public Information Campaigns and the Movement to “End Demand” for Prostitution in Atlanta, GA" Social Sciences 6, no. 4: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040138