Eluding National Boundaries: A Case Study of Commodified Citizenship and the Transnational Capitalist Class

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Question and Case Selection

1.2. Background

2. Commodification of the Dominica Citizenship

- (A)

- “Donation” to Government Fund

- ❑

- A—Single ApplicantNon-refundable investment of US $100,000

- ❑

- B—Family Application (one applicant plus spouse)Non-refundable investment of US $175,000

- ❑

- C—Family Application 2 (one applicant plus spouse and two children under age 18Non-refundable investment of US $200,000

- ❑

- D—Family Application 3 (one applicant plus more than two children under age 18)Non-refundable investment of US $200,000 and $50,000 for each additional person under age 18

- (B)

- Real Estate Investment

- ❑

- US $50,000 for the main applicant

- ❑

- US $25,000 for the spouse of the main applicant

- ❑

- US $20,000 for each child of the main applicant under eighteen (18) years of age

- ❑

- US $50,000 for each dependent of the main applicant above the age of eighteen (18) years, other than his or her spouse.

2.1. Dominica’s Commodified Citizenship in Context

2.2. Dominica’s Commodified Citizenship since 2004

3. Commodified Citizenship and the TCC

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boatca, M. Commodification of Citizenship: Global Inequalities and the Modern Transmision of Property. In Overcoming Global Inequalities; Wallerstein, I., Chase-Dun, C., Suter, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dominica News Online. PM Skerrit Says Value of CBI Should Never Be Underestimated. Dominica News Online, 10 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods., 2nd ed.; Sage Publishing: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 1st ed.; Sage Publishing: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gerring, J. Single-Outcome Studies: A Methodological Primer. Int. Sociol. 2006, 21, 707–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Political Sci. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, J. CBI Rankings. Available online: http://cbiindex.com/rankings (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Chen, M. Nation Loses Diplomatic Ally Dominica. Taipei Times, 31 March 2004. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Republic of Ministry of Commerce. China Establishes Diplomatic Relations with the Commonwealth of Dominica; MOFCOM: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jamaican Observer. China to Pump US $ 16m into Dominica. Jamaican Observer: Jamaica News Online, 3 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dominica Vibes. Dominica Reiterates Committed to One China Policy. Dominica Vibes, 24 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The American Interest Magazine. China “Takes Over” Island of Dominica. The American Interest Magazine (Online), 12 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guangqian, P.; Youzhi, Y. The Science of Military Strategy; Military Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13CBI Unit. Dominica Citizenship by Investment. Available online: https://cbiu.gov.dm/the-benefits/ (accessed on 25 July 2014).

- Henley & Partners. Henley & Partners Visa Restrictions Index. Available online: http://visaindex.com/# (accessed on 6 July 2017).

- Douglas, S.; Dominica, P.S. Prime Minister Skerrit Leads High Level Delegation to The People’s Republic of China. Dominic. 2005, 1 (71). Available online: http://www.thedominican.net/articles/chinanew.htm (accessed on 25 July 2014).

- The Sun Dominica. Skerrit: No Worries about Influx of Chinese. The Sun Dominica, 4 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DA Vibes. PM Hails Recent CBI Promotion Trip as Successful. DA Vibes: The Caribbean’s News Portal, 22 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniewicz, R.P.; Moran, T.P. Unveiling Inequality: A World Historical Perspective; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zolberg, A. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K.; Scully, B. A Hidden Counter-Movement? Precarity, Politics, and Social Protection before and beyond the Neoliberal Era. Theory Soc. 2015, 44, 414–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 20DNO Staff Writer. PM Defends “Red Clinic”. Dominica News Online, 28 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Skerrit, R. Budget Address for Fiscal Year 2017/2018; Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica: Roseau, Dominica, 2017.

- Huang, Y. Rethinking the Beijing Consensus. Asia Policy 2011, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi, G.; Zhang, L. Beyond the Washington Consensus: A New Bandung? In Globalization and Beyond: New Examinations of Global Power and Its Alternatives; Penn State Press: State College, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, L.; Mepham, D. The New Sinosphere: China in Africa; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sautman, B.; Hairong, Y. Friends and Interests: China’s Distinctive Links with Africa. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2007, 50, 75–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiwei, Z. The Allure of the Chinese Model. International Herald Tribune, 2 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam, D. The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ramo, J.C. The Beijing Consensus; Foreign Policy Centre: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Joppke, C. Transformation of Citizenship: Status, Rights, Identitiy. Citizensh. Stud. 2007, 11, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimmler, A.; Højlund, H.; Kristensen, N.N. Citizenship under Transformation. Distinktion Scand. J. Soc. Theory 2011, 12, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T. Citizenship as a Weapon. Citizensh. Stud. 2013, 17, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studemeyer, C.C. Geographies of Flexible Citizenship. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desforges, L. New Geographies of Citizenship. Citizensh. Stud. 2005, 9, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamian, A.A. The Cosmopolites: The Coming of the Global Citizens; Columbia Global Reports: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, V. Inherited Multiple Citizenships: Opportunities, Happenstances and Improvisations among Mobile Young Adults. Soc. Anthropol. 2014, 22, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faist, T. Dual Citizenship in Europe: From Nationhood to Societal Integration; Faist, T., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Macklin, A. Multiple Citizenship, Identity and Entitlement in Canada; Issue 6 of IRPP Study; Institute for Research on Public Policy: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Deth, J.W. New Modes of Participation and Norms of Citizenship. In Joint Sessions of the European Consortium for Political Research Workshop, “Professionalization and Individualized Collective Action: Analyzing New ‘Participatory’ Dimensions in Civil Society.”; European Consortium for Political Research: Lisbon, Portugal, 2009; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sprague-Silgado, J. The Caribbean Cruise Ship Business and the Emergence of a Transnational Capitalist Class. J. World-Syst. Res. 2017, 23, 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, H.A. Transnational Capitalist Globalization and the Limits of Sovereignty: State, Security, Order, Violence, and the Caribbean. In Caribbean Sovereignty, Development and Democracy in an Age of Globalization; Lewis, L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, H.A. (Ed.) Globalization, Sovereignty and Citizenship in the Caribbean; University of the West Indies: Mona, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.S. Citizenship and Capitalism: The Debate over Reformism; Allen and Unwin: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Isin, E.F.; Nyers, P. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Global Citizenship Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.S. (Ed.) Citizenship and Social Theory; Politics and Culture Series; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Isin, E.F.; Turner, B.S. (Eds.) Handbook of Citizenship Studies; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, J.; Philo, C. Spaces of Citizenship: An Introduction. Political Geogr. 1995, 14, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.I. A Theory of Global Capitalism: Production, Class, and State in a Transnational World; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heater, D. World Citizenship and Government; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 1996; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, C.; Clay, E. Economic and Financial Impacts of Natural Disasters: An Assessment of Their Effects and Options for Mitigation : Synthesis Report; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, C.; Clay, E. Dominica: Natural Disasters and Economic Development in a Small Island State; Disaster Risk Management Working Paper Series; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio, L. Small Island Developing States and Their Economic Vulnerabilities. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1615–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, J. Budget Address of Fiscal Year 1996/1997; Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica: Roseau, Dominica, 1996.

- International Monetary Fund. Dominica: Second Review Under the Three-Year Arrangement Under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility and Request for Waiver of Performance Criterion—Staff Report; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, P. Caribbean Warms to Beijing. Asia Times (Online), 20 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K. The Spectre of Global China. New Left Rev. 2014, 89, 29–65. [Google Scholar]

- Simoes, A.; Hidalgo, C.A. The Economic Complexity Observatory: An Analytical Tool for Understanding the Dynamics of Economic Development. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. In 2011 Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sklair, L. Sociology of the Global System, 1st ed.; Johns Hopins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sklair, L. Sociology of the Global System. In Globalization: The Reader; Lechner, F., Boli, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NCU Media Group. Corruption-Accused Nigerian Minister Issued Dominica Diplomatic Passport. NCU Media Group, 21 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dominica Vibes Online. Dominica Cancels Diplomatic Passport of Iranian Businessman. Dominica Vibes Online, 26 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zagaris, B. Antigua and Dominica Make Changes to Diplomatic Passports as Proper Regulation of Citizenship-by-Investment Continues to Be an Issue for the Caribbean. Cayman Financial Review, 18 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dunaway, W.; Clelland, D. China’s Going Out: The Ethnic Complexities of Semiperipheral Transnational Capitalism in Sub-Saharan Africa 2000–2015. In American Sociological Association Annual Meeting; American Sociological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Green, T. (GIS). Government Signs over $ 18 Million Agreement with China. Dominica News Online, 12 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- DNO Staff Writer. Tremendous Opportunities for Dominica in South East Asia—PM Skerrit. Dominica News Online, 16 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DA Vibes. PM’s CBI Promotion Tour “Very Successful”. DA Vibes: The Caribbean’s News Portal, 18 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- China Merchants Bank; Bain and Company. China Private Wealth Report—China’s Private Banking Industry: Competition Is Getting Fierce; China Merchants Bank: Shenzhen, China, 2011; Volume 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, W.I. The Transnational State and the BRICS: A Global Capitalism Perspective. Third World Q. 2015, 36, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.I. Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, A.; Nonini, D.M. Chinese Transnationalism as Alternative Modernity. In Ungrounded Empires: The Cultural Politics of Modern Chinese Transnationalism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Staff Writer. Kempinski Hotel Project Moving Forward in Dominica. Caribbean Journal, 18 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow, W.W. Stages of Economic Growth. Econ. Hist. Rev. 1959, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominica Vibes Online. New West Bridge Officially Commissioned. Dominica Vibes Online, 1 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Skerrit, R. Budget Address for Fiscal Year 2015/2016; Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica: Roseau, Dominica, 2015.

- International Monetary Fund. Dominica: Selected Issues; IMF Country Report 17/392; April 27, 2017; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Skerrit, R. Budget Address of Fiscal Year 2011/2012; Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica: Roseau, Dominica, 2011.

- Skerrit, R. Budget Address for Fiscal Year 2014/2015; Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica: Roseau, Dominica, 2014.

| 1 | For a snapshot of Dominica’s key development indicators, see https://data.worldbank.org/country/Dominica. |

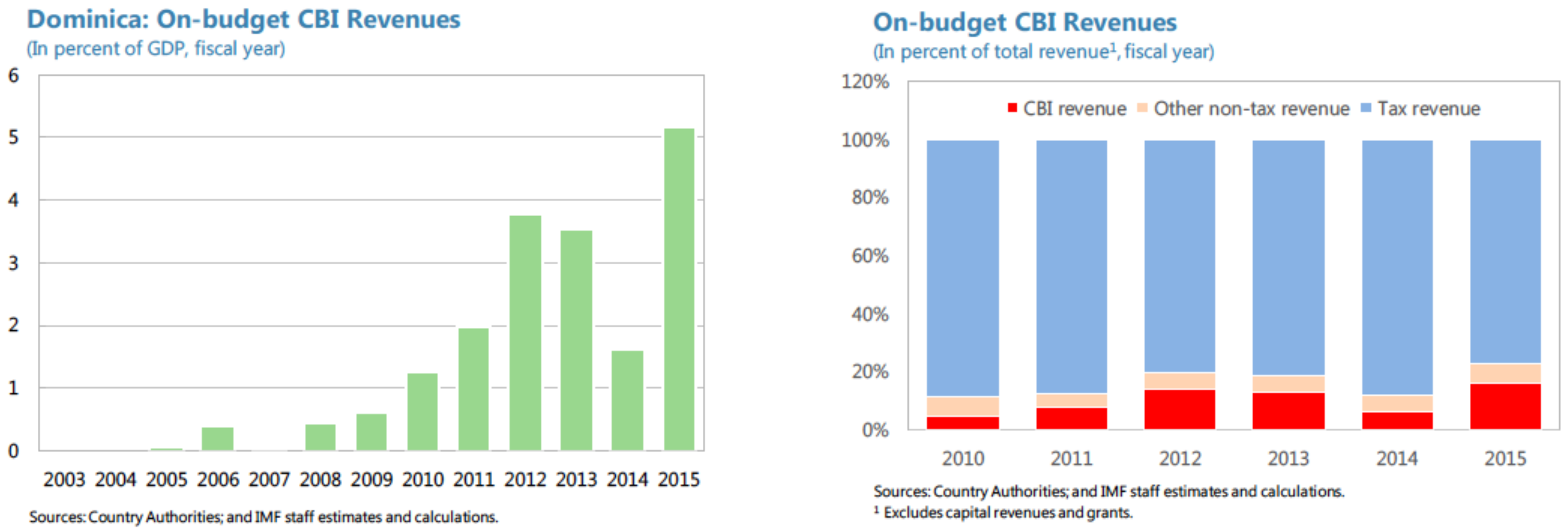

| 2 | See Figure 1. More citizenships were sold in 2013 alone compared to the years 1990–2003 combined. |

| 3 | CARICOM is a union of 20 countries the main objective of which is economic integration and the coordination of foreign policy. CARICOM is home to 60 million people and includes islands in the Caribbean, Guyana, Suriname, and Belize. http://caricom.org/about-caricom/who-we-are/. |

| 4 | The Caribbean Basin Initiative provides duty-free access to US markets for most goods. https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/trade-development/preference-programs/caribbean-basin-initiative-cbi. |

| 5 | One-China Policy is a foreign relations approach in which the PRC requires its partners to accept that there is one legitimate government which represents the people of China and to engage in diplomatic relations with the PRC means breaking relations with the ROC (Taiwan). This policy is based on the idea that “if Taiwan should be alienated from the mainland, China will forever be locked to the west side of the first chain of islands in the West Pacific, and … the essential strategic space for China’s rejuvenation will be lost” [13]. |

| 6 | TCC in this article means those seeking to organize the conditions under which global capital and the global system under which it operates can be furthered within the transnational, interstate, national, and local contexts. |

| 7 | For an in-depth look at the proliferation of social assistance in the form of “Red Clinics” in the developing world as a response to the neoliberal era, see Kevan Harris and Ben Scully’s paper [21], A Hidden Counter-Movement? |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | This is part of an ongoing project by the author that began in 2014. The author has collected data (and continues to collect data) on naturalized citizenship in Dominica (including citizenship by cash payment, purchase of real estate, and residency). This data includes the names of these citizens, their countries of origin, their countries of residency, and the year they received their citizenship. |

| 11 | Taiwan ICDF (established in 1996) has its roots in the International Economic Cooperation Development Fund (IECDF), which was started during the height of Taiwan’s economic boom, to provide economic assistance to its developing partner countries. Today, ICDF provides lending and investment, technical cooperation, humanitarian assistance, and international education and training for its partner countries. In the Caribbean, it is part of the ROC’s continuing efforts to preserve its existing foreign relationships with the developing world especially given the increasing Chinese influence in those regions. |

| 12 | Formed in 1981, the OECS is an intergovernmental organization dedicated to economic harmonization and integration, protection of human and legal rights, and the encouragement of good governance between 7 (now 10) countries in the Eastern Caribbean. http://www.oecs.org/. |

| 13 | Dominica has a small population of indigenous people called the Kalinago. The Carib Territory was established in 1903 by British colonial authorities. The Carib people refer to themselves as the Kalinago People and in 2015 lobbied the government to officially rename the Carib Territory the Kalinago Territory. |

| 14 | The idea of a “cabbage strategy” is attributed to Chinese military theorist and member of the People’s Liberation Army Navy, Zhang Zhaozhong. It involves asserting a territorial claim and gradually surrounding the area with multiple layers of security, thus denying access to a rival. The strategy relies on a steady progression of steps to outwit opponents and create new facts on the ground. |

| 15 | That tendency to present China as an all-encompassing entity when studying its relationship with countries both in the Global North and South has been diminishing in academia. A good example, would be C.K. Lee’s article for the New Left Review [57] calling for more sophistication in studying China’s relation to the world. |

| 16 | One could also argue that criminals are also natural consumers of commodified citizenship. However, for now, the expectation is that countries like Dominica that engage in commodified citizenship are doing their due diligence with regards to the sale of citizenships. Of course, like other small island nations engaging in commodified citizenship, Dominica has experienced its share of scandals (such as the Nigerian former Minister of Petroleum Resources, Diezani Alison-Madueke, being issued a diplomatic passport on 29 May 2015, within one month of meeting Dominica’s Prime Minister R. Skerrit—Madueke was being investigated for corruption in Great Britain [61]; and Alireza Zibahalat Monfared who was carrying a diplomatic passport of Dominica when he was arrested during an international manhunt [62]) that the Skerrit administration is addressing through a series of policy changes [63]. Both cases involve diplomatic passports, which is mostly left to the discretion of the Prime Minister. This aspect of the commodified citizenship program is important but should be best pursued in a different article due to space limitations here. |

| 17 | The data is collected from the Commonwealth of Dominica Official Gazette, Published by Authority, Roseau, Dominica. Each year, a number of volumes are published documenting official government announcements. The gazettes are mined for data for each year from all the issues beginning with Volume CXVI No. 20 to Volume CXXXIX No. 14. Every first and last name, the country of current citizenship, the country of residence, country of birth, and date registered as a Dominican citizenship through the citizenship by investment (CBI) program are recorded. Figure 1 provides a summary of this data. |

| 18 | Here, I mean development either from the point of view of industrialization/manufacturing as a means of “catching up” (à la Rostow [73]) or from a poverty reduction/sustainable development perspective. |

| Name of Authorized Agency | Location of Offices |

|---|---|

| AAA Investor Immigration Ltd. | Roseau |

| Alick C. Lawrence Chambers/The Nestman Group Ltd. | Roseau |

| Apex Capital Partners | Roseau and Moscow |

| Arton Capital (Dominica) Ltd. | Roseau |

| Bayat Law Group Inc. | Dubai |

| Belnor Associates Inc. | Roseau |

| Caribbean Citizenship Inc. | Roseau |

| Caribbean Commercial & IP Law Practitioners LLP | Roseau |

| Passpro Immigration Services | Dubai |

| Caribbean Consulting Services Ltd. | Roseau |

| Caribbean Consulting Service Ltd. | Rotterdam |

| Caribbean –Sino Consulting Services Ltd. | Zicak, Portsmouth |

| CCP Inc. | Roseau |

| Citizenship Invest Ltd. | Roseau |

| CTrust Global Ltd. | Dubai |

| De Freitas, De Freitas & Johnson Chambers | Roseau |

| Design Management Ltd. | Roseau |

| Dominica International Investment Corporation Ltd. | Roseau, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, |

| Duncan G. Stowe | Roseau |

| Global Citizenship Programs Ltd. | Roseau |

| Guide Consultants Inc. | Roseau |

| Harvey Law Group | Roseau |

| IMT Inc. | Roseau |

| Lennox Lawrence | Roseau |

| Lennox Lawrence (Vardikos and Vardikos) | Athens |

| Lennox Lawrence (Alfred Management and Business Consultancy) | Dubai |

| Lennox Lawrence (Corporate Solutions) | St. Kitts |

| Modern Agricultural Ventures Inc. | Roseau |

| Montreal Management Consultants Est. Ltd. | Morne Daniel, Roseau, Sharjah |

| NL Citizenship Ltd. | Roseau |

| Paradise Citizens | Roseau |

| Savory and Partners | Dubai |

| Second Citizenship Ltd. | Roseau |

| Sunstone Incorporated—Tranquility BeachDominica DOMINICA | Roseau |

| Verlyn Liz-Ann Faustin | Roseau |

| Whitco Inc. | Roseau |

| Financial Year | Project Description | Budget in Millions XCD | Actual Exp. in Millions XCD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009–2010 | Const. Melville Hall Fire Station | 1 | 0.73 |

| Reconst. of Portsmouth Secondary School | 1.71 | 1.5 | |

| Rehab. of West Coast Road | 5.81 | 5.81 | |

| 2010–2011 | Const. Melville Hall Fire Station | 2 | 1.28 |

| Rehab. of West Coast Road | 44.18 | 44.18 | |

| Repairs to Primary Schools | 0.214 | 0.214 | |

| Assistance to Farmers affected | |||

| by Hurricane Tomas | 0.28 | 0.28 | |

| Housing Assistance in LaPlaine | 0.045 | 0.045 | |

| 2011–2012 | Const. Melville Hall Fire Station | 3 | 1.93 |

| Reconst. of Newtown Primary School | 0.4 | 0.376 | |

| Const. Carib Territory Housing Project | 1.3 | 1.29 | |

| Rehab. of West Coast Road | 25 | 41 | |

| Assistance to Layou River Flood Victims | 0.37 | 0.21 | |

| 2012–2013 | Const. Carib Territory Housing Project | 2.6 | 1.48 |

| Const. Melville Hall Fire Station | 1.8 | 1.24 | |

| 2012–2014 (YTD) | Const. Carib Territory Housing Project | 1.29 | 0.84 |

| YTD:8/2014 | 90.999 | 102.405 |

| IMPORTS | |

|---|---|

| 2002 Total = $185M US—5% ($46.9M) China—5% ($28.7M) Trinidad and Tobago—11% ($19.6M) South Korea—7.5% ($14M) UK—6.7% ($12.4M) Japan—5.5% ($10.3M) | 2008 Total = $361M US—32% ($117M) Trinidad and Tobago—13% ($48.8M) China—13% ($48.7M) UK—3.6% ($12.9M) |

| 2004 Total = $213MUS—27% ($56.8M) China—12% ($26.3M) Trinidad and Tobago—11% ($23.7M) UK—7.7%($16.5M) South Korea—4.4% ($9.31M) France—3.7% ($7.87M) | 2010 Total = $321M US—30% ($96.3M) Trinidad and Tobago—10%($33.2M) China—9.8% ($31.4M) |

| 2006 Total = $272M US—29% ($79.8M) Trinidad and Tobago—14% ($37.5M) China—14% ($37.1M) UK—4% ($10.9M) | 2012 Total = $258M US—32% ($82M) Trinidad and Tobago—13% ($34.4M) China—5.9% ($15.3M) |

| EXPORTS | |

|---|---|

| 2002 Total = $68.1M UK—32% ($21.7M) Jamaica—14% ($9.59M) US—8.5% ($5.8M) France—5.9% ($4.02M) Antigua and Bermuda—5.2% ($3.5M) | 2008 Total = $97.3M Saudi Arabia—12% ($11.5M) Vietnam—12% ($11.2M) Jamaica—7.7% ($7.5M) UK—7.6% ($7.38M) France—7.5% ($7.25M) Trinidad and Tobago—5.2% ($5.07M) |

| 2004 Total = $77.1M UK—22% ($16.8M) Jamaica—12% ($8.96M) France—10% ($7.71M) Japan—5.5% ($4.23M) Antigua and Bermuda—5.4% ($4.14M) | 2010 Total = $59.2M Jamaica—14% ($8.3M) UK—7.8% ($4.64M) France—7.6% ($4.49M) Trinidad and Tobago—7.4% ($4.36M) Saudi Arabia—5.7% ($3.39M) |

| 2006 Total = $80.9M UK—20% ($16.4M) Jamaica—10% ($8.45M) China—9.8% ($7.9M) Antigua and Bermuda—7.2% ($5.85M) France—6.5% ($5.26M) | 2012 Total = $81.4M Jamaica—12% ($9.74M) Trinidad and Tobago—8.5% ($6.91M) Saudi Arabia—7.7% ($6.26M) Sweden—5.6% ($4.95M) |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grell-Brisk, M. Eluding National Boundaries: A Case Study of Commodified Citizenship and the Transnational Capitalist Class. Societies 2018, 8, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020035

Grell-Brisk M. Eluding National Boundaries: A Case Study of Commodified Citizenship and the Transnational Capitalist Class. Societies. 2018; 8(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrell-Brisk, Marilyn. 2018. "Eluding National Boundaries: A Case Study of Commodified Citizenship and the Transnational Capitalist Class" Societies 8, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020035