Abstract

Groundwater pumping along portions of the binational San Pedro River has depleted aquifer storage that supports baseflow in the San Pedro River. A consortium of 23 agencies, business interests, and non-governmental organizations pooled their collective resources to develop the scientific understanding and technical tools required to optimize the management of this complex, interconnected groundwater-surface water system. A paradigm shift occurred as stakeholders first collaboratively developed, and then later applied, several key hydrologic simulation and monitoring tools. Water resources planning and management transitioned from a traditional water budget-based approach to a more strategic and spatially-explicit optimization process. After groundwater modeling results suggested that strategic near-stream recharge could reasonably sustain baseflows at or above 2003 levels until the year 2100, even in the presence of continued groundwater development, a group of collaborators worked for four years to acquire 2250 hectares of land in key locations along 34 kilometers of the river specifically for this purpose. These actions reflect an evolved common vision that considers the multiple water demands of both humans and the riparian ecosystem associated with the San Pedro River.

1. Introduction

Many aquifers within the United States contain an essential—yet shrinking—supply of water for both people and natural systems. Groundwater resources support the irrigation of crops, drinking water supplies, and industry. Declining groundwater levels strongly affect riparian ecosystems in the semi-arid southwestern United States, where many aquifer systems are characterized by a large volume of water in storage, but a relatively small rate of natural annual recharge and discharge [1]. Because groundwater also supports natural systems such as wetlands, riparian systems, lakes, streams, and rivers, it has become increasingly difficult for water managers in this region to meet both increasing human water demands and the water needs of natural systems under persistent drought conditions [1,2]. In Arizona, perennial streamflows have significantly declined across the state—at least seven river systems could be dewatered over time, and an additional four will experience degradation if actions are not taken to reverse these trends [2]. In other words, it is increasingly difficult to manage groundwater supplies sustainably in either short or long time frames.

Widespread acceptance/adoption of “sustainable yield,” which acknowledges long-term impacts of human pumping but tries to balance those impacts with environmental flow needs, represents a paradigm shift in groundwater management from the more common “safe yield” management paradigm that assumes it is acceptable for consumptive human uses of water to equal groundwater inflows. The name “safe yield” implies some level of security in terms of water availability, which by the very definition of the term is not afforded to water dependent natural systems if they are downstream of human water uses. Sustainable yield, on the other hand, more broadly addresses social, economic and environmental aspects of water availability. The methods for estimating sustainable yield, however, remain largely subjective and poorly understood by the general public, decision makers, and even water resources professionals.

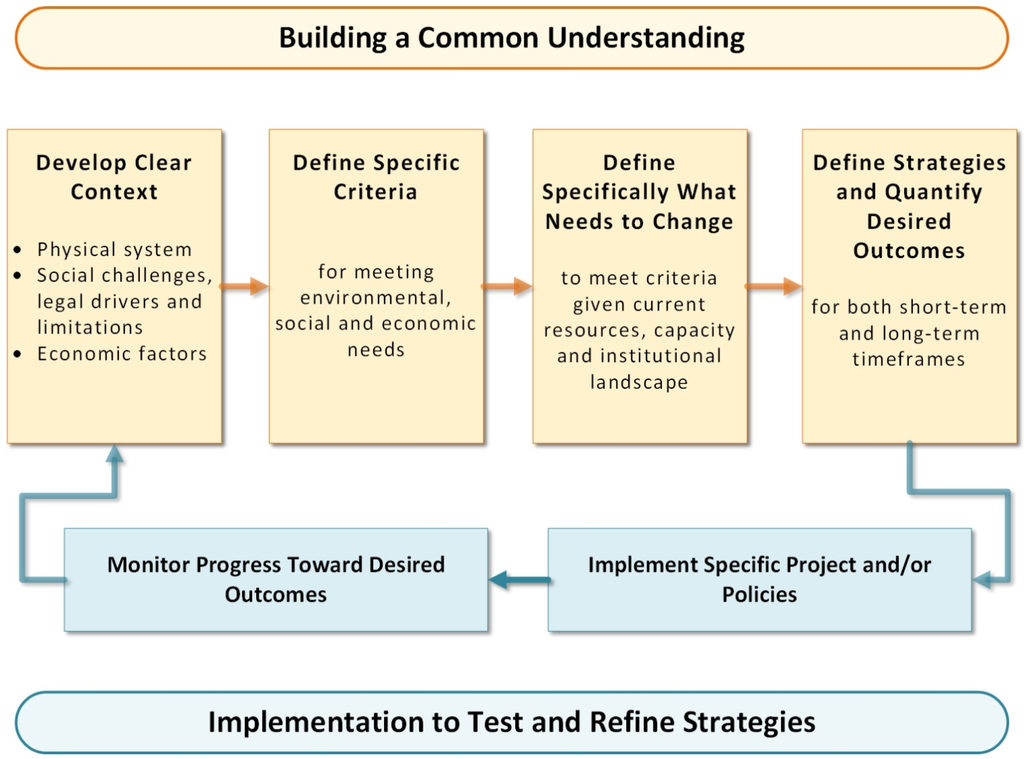

This paper provides a regional case study of the Upper San Pedro River Basin of southeastern Arizona where groundwater management has focused for over a decade on the goal of sustainable groundwater yield, and proposes a generic framework for stakeholder engagement in this process, as well as lessons learned. While several questions and challenges persist, and the implementation of key strategies is ongoing, we present the tools and processes that have proven effective to date there. In particular, we offer a clear definition of sustainable use of groundwater, a conceptual framework for collaborative regional efforts to work toward attaining it along with an example of how the framework was applied in the basin, and examples of specific policies and projects that were developed to foster sustainable use there.

2. The Upper San Pedro Basin

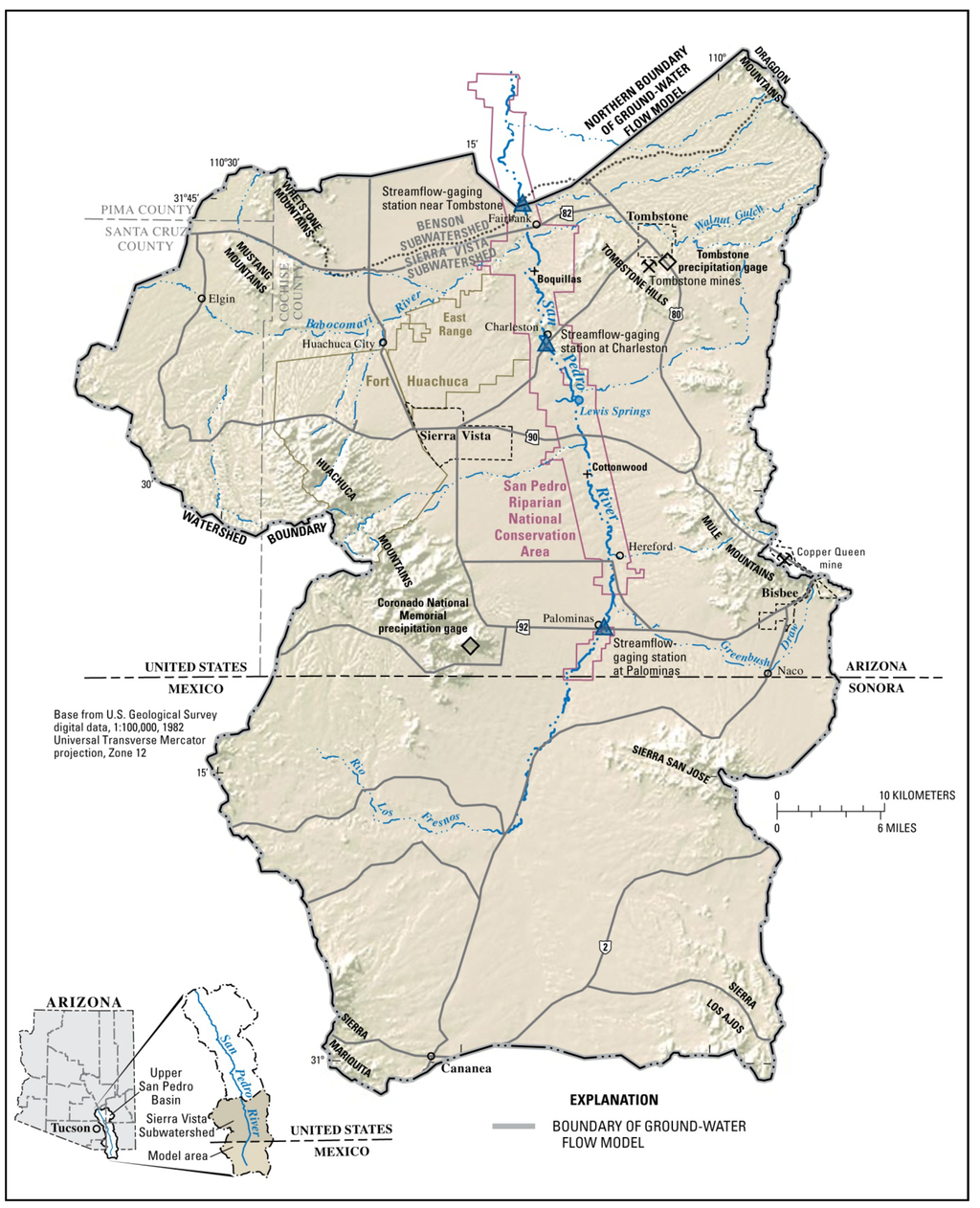

The Upper San Pedro Basin lies within the Basin and Range Province of the southwestern United States and is roughly bisected by the international boundary between Mexico and the United States (Figure 1). The basin is bounded on the east, west, and south by mountains that drain to the river near the center of the alluvial valley. The basin contains up to 520 meters of fill accumulated during the late Tertiary and early Pleistocene [3]. Runoff from the mountains recharged the basin fill over millennia, creating a vast aquifer underlying the San Pedro River. Today, dry-season flows in the San Pedro River depend almost entirely on groundwater discharge. In recent years, concern over potential pumping-related depletions of fragile surface water supplies has lent urgency to efforts to integrate the management of these two connected resources.

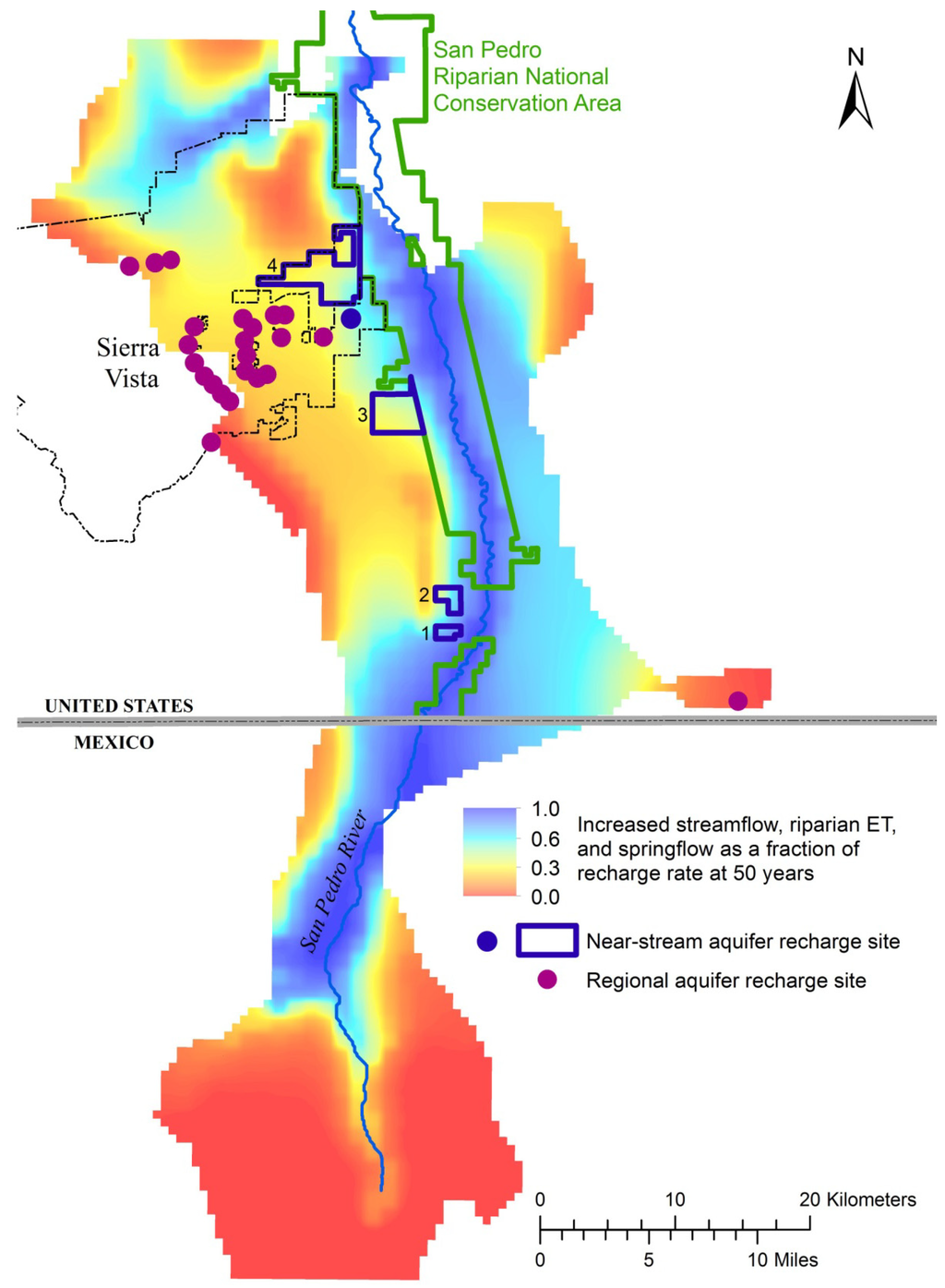

Figure 1.

Map of the Upper San Pedro Basin showing the location of the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Army installation at Fort Huachuca within the Sierra Vista Subwatershed, just north of the United States—Mexico international boundary. From [4] (Figure 1).

Despite the fact that Arizona law generally does not recognize the hydrologic connection between groundwater and surface water, collaboration aimed at integrated groundwater-surface water management in the Upper San Pedro basin has been ongoing for decades, both within the United States and, to a lesser extent, between the United States and Mexico. The State of Arizona is in the process of delineating the “subflow zone” of river alluvium adjacent to the San Pedro River in order to protect senior surface water rights. Management, monitoring and modeling efforts focused on groundwater-surface water interactions in the Sierra Vista Subwatershed (Subwatershed) have supported vital scientific understanding of the physical basin. However, building a shared vision toward such an integrated water management approach along the binational San Pedro River is challenging for many reasons, including: differences in the political structure, economic development, cultural norms and values, water law, and language on either side of the border combined with a highly variable and complex physical system. Browning-Aiken et al. [5] laid out some of the processes used for collaborative watershed management of the San Pedro based on the principles of collective action theory, dispute resolution, adaptive management, power dynamics, and sustainability. The complex binational legal constraints pertinent to San Pedro water issues were also described by Browning-Aiken et al. [6]. This paper, however, focuses only on activities on the United States side of the border.

Within the United States, Congress created the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA) in 1988 [7], the first Riparian National Conservation Area of its kind in the nation, and charged the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, to manage it “…in a manner that conserves, protects, and enhances the riparian area…” and other resources. This streamside riparian habitat, composed of Fremont cottonwood, Goodding willow, mesquite bosques, and sacaton floodplain grasslands, supports high levels of biodiversity and functions as a migratory bird corridor of hemispheric importance [8]. It includes approximately 64 km of the 279-km river that flows north to eventually join the Gila River, itself a tributary river to the larger Colorado River (Figure 1).

Several miles away from the SPRNCA another national asset, the U.S. Army installation at Fort Huachuca, had its own needs for groundwater to sustain its military mission associated with national security including communications testing. Fort Huachuca represents a major driver for southern Arizona’s economy as the largest employer in the region and contributes approximately $2 billion (U.S.) annually to the state’s economy [9]. Located between these two federal interests, the residents of the City of Sierra Vista and Cochise County depend upon the same limited groundwater resources as the National Conservation Area and Fort Huachuca.

In terms of the legal and regulatory context, there are no state restrictions on groundwater extraction along the San Pedro River except for pumping from the zone of subflow, typically a narrow band along the river corridor corresponding to fluvially deposited alluvium. In Arizona, the legal priority of surface water rights is governed by the claim filing date: the earlier the filing date, the more senior and defensible the water right. However, a comprehensive adjudication of water rights on the Gila River system has been ongoing for decades, including federal and other water rights claims along the San Pedro, therefore, considerable uncertainty regarding the nature of surface water rights continues to exist. However, there is a clear legal distinction between surface water rights, which can be defended against more junior competing surface claims, and groundwater use, which is almost wholly unregulated in the state outside of specifically designated Active Management Areas.

Arizona law prevents placing any use limitations—or even requiring a water meter—on wells with a maximum pump capacity of 132 liters/min or less [10], even within the state’s Active Management Areas. While the Upper San Pedro River Basin is outside of any state groundwater management area, Cochise County is one of only two counties in Arizona that have adopted requirements that subdivisions in the County must obtain a Designation of Water Adequacy. This program, administered by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) requires water companies or subdivisions to show proof of a 100-year water supply before development is permitted. A total of twenty-seven privately owned local water utilities that depend upon groundwater supplies are regulated at the state level by the Arizona Corporation Commission and Arizona Department of Environmental Quality and operate in the area. In addition, three public water supply providers operate municipal water utilities.

3. History of Collaborative Water Management in the Basin

A consortium named the Upper San Pedro Partnership (Partnership) was created through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in 1998 in response to the Arizona Department of Water Resources Rural Watershed Initiative. This collaboration also developed, at least partially, in response to a situation where “dueling hydrologists” hired by different factions provided widely varying opinions about the fate of groundwater and the San Pedro River. The Partnership provided a vehicle for local jurisdictions to work together alongside a range of federal and state agencies, as well as with non-governmental organizations and business interests. The organization’s purpose is to meet the long-term water needs of both the SPRNCA and the area’s residents [11]. According to the Partnerships mission statement, this goal is to be accomplished through the identification, prioritization, and implementation of policies and projects related to groundwater conservation and (or) enhancement [12].

One of the first objectives for the Partnership was to create a collaboratively-developed regional groundwater model on which all interests could agree and then utilize it for decision making. The model, developed by the USGS, was funded through multiple federal agency budgets, with additional supporting studies funded by other some of the other Partnership members. Over the course of the five years it took to build, USGS hydrologists provided a high level of transparency about the structure of the model and the empirical data sources used to calibrate it [8]. Ultimately, this collaborative model building process served to establish a clear context and common understanding of the complexities of the hydrogeology, surface and groundwater systems, human water demands, and riparian vegetation trends and water needs. During this time, the Partnership was also recognized (in 2003) by the U.S. Congress via Public Law 108-136, (Section 321) [13], which charged the Partnership with achieving sustainable yield of the Sierra Vista Subwatershed regional aquifer by 30 September 2011.

The Section 321 legislation also required the U.S. Secretary of the Interior to deliver nine annual reports to Congress on the water management and conservation measures necessary to restore and maintain the sustainable yield of the regional aquifer by and after 30 September 2011. Future federal appropriations to the Partnership were to depend on the Partnership’s ability to meet its annual goals for groundwater deficit reduction. On behalf of the Secretary and following Partnership decisions about methods and content, the reports were compiled and written by USGS staff of the Arizona Water Science Center with the assistance of other Partnership members. What the 321 legislation did not provide was a Congressional definition of the term “sustainable yield of the regional aquifer.”

The Partnership chose a definition of sustainable yield based on the competing objectives view of sustainability [14]

“…managing [groundwater] in a way that can be maintained for an indefinite period of time, without causing unacceptable environmental, economic, or social consequences”.[15]

This was operationalized to mean, “…a sustainable level of groundwater pumping for the Sierra Vista subwatershed could be an amount between zero and a level that arrests storage depletion, with the understanding that to call a level of use sustainable (other than zero) will entail some consequences at some point in the future” [16].

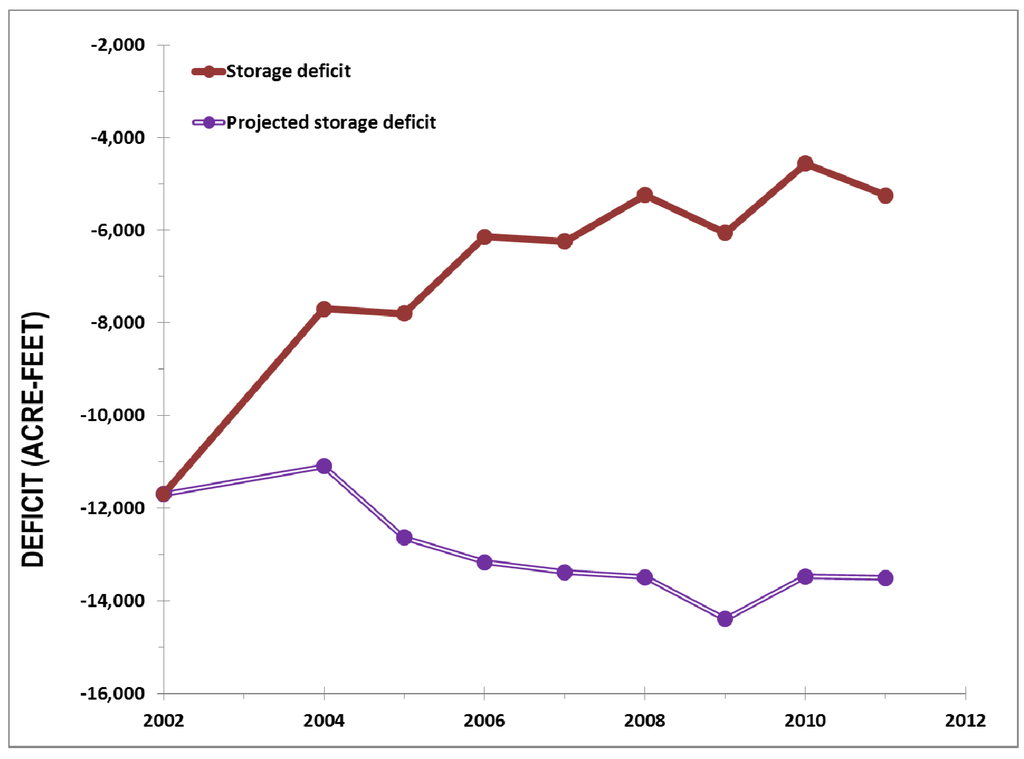

Figure 2 summarizes the progress of the 23 member agencies in their collaborative efforts to reduce the groundwater deficit through water conservation, recharge and reuse programs after the Section 321 legislation was enacted.

Figure 2.

Estimated actual Sierra Vista subwatershed annual storage deficit and projected annual storage deficit that would have occurred had no management, conservation, or incidental yields due to human activity taken place. Incidental yields include increased recharge of runoff due to urbanization. The projected annual storage deficit is based on 2002 pumping rates and actual (not projected) population data from the State of Arizona and the U.S. Census through 2012. Modified from [17].

5. Results and Conclusions

Based on the San Pedro experience, approaches such as the Partnership that directly engage affected policy makers, stakeholder organizations, regulatory agencies, and the scientific community can more effectively implement the necessary projects or policies, than if the partners were addressing the same challenge as individual interests. The involved partners more deeply understand the need for management measures, but are engaged in the actual exploration and development of possible alternatives, and witness the results and progress toward specific desired outcomes through adaptive management over time [35]. This was certainly the case for the Partnership as they first quantified the annual yield from a wide array of member agency water conservation, reuse, and recharge projects, then implemented dozens of them since 1998 [6] (Figure 2).

However, the Upper San Pedro Basin is unique in many ways. The presence of an important federal military installation and a federally protected riparian corridor within the Sierra Vista Subwatershed have brought a level of interest and involvement absent from many other basins with similar hydrogeologic conditions. The federal nexus in water issues has also resulted in significant funding to assess groundwater pumping impacts and to help mitigate those effects. Without Congressional funding for the Partnership and much of the federally-sponsored scientific research that supported development of the groundwater model, the state of the science would likely not have advanced to its current level.

Despite these unique socio-political aspects, the San Pedro Basin represents one of the best examples of riparian corridors remaining in the desert Southwest. The Gila River that drains more than 60% of the state no longer has any undammed perennially flowing segments, and is dry over most of its length. Many of the state’s once-flowing, now-dry rivers reflect the impacts of long-term groundwater pumping in the mid to late 20th century. They provide a stark reminder of how directly connected groundwater and surface water resources are for our desert rivers.

5.1. Lessons Learned

- Lesson 1: Engage decision makers and key stakeholders early in the process to define the science and technical tools needed for an integrated water management approach.These needs should be tailored explicitly to the existing conceptual models of key stakeholders, and the gaps in understanding, disagreements and/or misperceptions that they hold. This approach strengthens the foundation for shaping meaningful criteria for success, the formation of effective strategies, and the definition of meaningful desired outcomes. The Upper San Pedro provides an example of a stakeholder-driven process where project implementation was driven by an evolving science-based understanding of the system, and additional financial resources and political support were generated over time in response to an enhanced understanding and appreciation of the challenges and opportunities. As stakeholders progressively learned more about the system, they were also in a better position to make the case for generating additional public and private funding to support their efforts.

- Lesson 2: Collaboratively define desired outcomes as specifically as possible both temporally and spatially.The process of defining “sustainable yield” for the San Pedro is still underway more than 11 years after Congress mandated its implementation in the Subwatershed. By some measures, such as per-capita water consumption rates and managed aquifer recharge, efforts to mitigate the effects of groundwater pumping have been very successful. However, developing the predictive models to more specifically understand the response of the physical system allowed decision makers to recognize that, while their previous efforts would aid in slowing overall aquifer storage depletion, they would not necessarily protect the river from pumping-induced capture in shorter time frames (years to decades). Later efforts to initiate near-stream recharge arose from a better understanding of both the spatial and temporal aspects of the system, and strengthened the recognition that both short-term and long-term actions and effects were important.

- Lesson 3: Stakeholders with varied interests are more likely to work successfully toward a common goal if they feel that their individual interests are represented, and can actually benefit from the process.Challenging economic and legal contexts should not prevent diverse parties from working toward a solution if they perceive that their interests are represented in, and perhaps even benefit from a shared vision with other interests. Even though some objectives may seem to be competing (e.g., preserving reasonable depths to groundwater for water supply wells AND preserving baseflows in the river), finding a common thread among the parties—such as preservation of a vital economic driver for the region—can lead diverse parties to define and accept a mutually beneficial outcome. Once stakeholders recognize what outcomes of a solution might look like (such as baseflow supported by near-stream recharge), they may better reach consensus about how to achieve that proposed solution. For the San Pedro, the acknowledgement of all three aspects of sustainability—economic, social and environmental—helped to build trust, agreement and eventually support among interests. In addition, it opened conversations to the consideration of more specific objectives aimed at both the short- and long-term. The parties acknowledged that preserving flow in the river was the most immediate short-term concern, while also recognizing the need for longer-term efforts to maintain supplies at municipal pumping centers.

- Lesson 4: The importance of effective communication and two-way learning between scientists and decision makers cannot be overstated.While scientists and subject experts may recognize specific physical trends and processes in respect to hydrologic systems, other stakeholders may not agree on the nature or even the existence of them. Conversely, water managers and decision makers function within an operating environment that includes many dynamic political, financial, and legal factors that are not clear to scientists. Developing a shared understanding of these challenges as they relate to key water management decisions may take years. How do we help decision makers with little or no technical knowledge of complex groundwater hydrology understand that the pumping of half a century ago will manifest as declines in baseflow over the next half century? Even more problematic is trying to convince them to invest in expensive solutions to a crisis that—if the solution works—will never materialize. Accepting these hydrologic “mysteries” that are taking place in an invisible underground system they will never see requires a considerable leap of faith.The burden lies with both the scientific community and decision makers to invest the required time and effort communicating and learning about the environmental, social, and economic aspects of regional water management to be able to develop meaningful collaborative strategies together. The development of a set of specific criteria for meeting environmental, social, and economic needs as part of a shared vision of sustainable groundwater management is an essential first step toward the development of that understanding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the support of the Upper San Pedro Partnership, and its respective 23 member agencies, over the past 15 years in developing the science and fostering the collaboration required for the progress that has been made toward groundwater sustainability in the Upper San Pedro Basin. The USGS has also made significant contributions toward not only the development of the groundwater model in the basin, but also toward the conceptual understanding of sustainable yield on a broader basis. Lacher Hydrological Consulting has played a pivotal role in running various groundwater model simulations. The Department of Defense Army Compatible Use Buffer (ACUB) Program provided significant funding for the acquisition of land for aquifer recharge sites, and the Walton Family Foundation generously provided private funding for the subsequent design and engineering of initial aquifer recharge facilities. The authors thank David Goodrich and two anonymous reviewers for substantially improving this article.

Author Contributions

The text of this article was written by Holly E. Richter, Bruce Gungle, Laurel J. Lacher, Dale S. Turner and Brooke M. Bushman. Holly E. Richter and Bruce Gungle wrote the bulk of the history of the partnership and development of the shared vision content. Laurel Lacher helped formulate the basic concept of the paper, provided input on the concept of sustainable groundwater use, and assisted with organizing the paper’s structure. Dale S. Turner conducted background research on the technical tools, helped hone the sustainable yield concepts, provided content review, and also served as our primary internal editor. Brooke Bushman added current project implementation content, developed several figures and maps, and also provided content review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Webb, R.H.; Leake, S.A. Ground-water surface-water interactions and long-term change in riverine riparian vegetation in the southwestern United States. J. Hydrol. 2006, 320, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.M.; Robles, M.D.; Majka, D.R.; Haney, J.A. Sustainable water management in the southwestern United States: Reality or rhetoric? PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.G.; Davidson, E.S.; Kister, L.R.; Thomsen, B.W. Water Resources of Fort Huachuca Military Reservation, Southeastern Arizona; Water-supply Paper 1819-D; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1966; pp. D1–D57.

- Pool, D.R.; Dickinson, J.E. Ground-Water Flow Model of the Sierra Vista Subwatershed and Sonoran Portions of the Upper San Pedro Basin, Southeastern Arizona, United States, and Northern Sonora, Mexico; Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5228; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2007; p. 47.

- Browning-Aiken, A.; Richter, H.; Goodrich, D.; Strain, B.; Varady, R. Upper San Pedro Basin: Fostering collaborative binational watershed management. Water Resour. Dev. 2004, 20, 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Browning-Aiken, A.; Varady, R.; Richter, H.; Goodrich, D.; Sprouse, T.; Shuttleworth, W.J. Integrating Science and policy for water management: A case study of the Upper San Pedro Basin. In Hydrology and Water Law-Bridging the Gap; Wallace, J., Wouters, P., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arizona-Idaho Conservation Act of 1988. Public Law 100-696 Title 1, 1988.

- Skagen, S.K.; Melcher, C.P.; Howe, W.H.; Knopf, F.L. Comparative use of riparian corridors and oases by migrating birds in southeast Arizona. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, R. Economic Impact of Fort Huachuca. Undated White Paper. Available online: http://www.cochise.edu/cfiles/files/CER/CER%20Studies/Economic_Impact_of_Fort_Huachuca.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2014).

- Exemption of small non-irrigation wells; definitions. Arizona Revised Statutes Section 45-454, 2013.

- Upper San Pedro Partnership History. Available online: http://www.usppartnership.com/about_history.htm (accessed on 16 June 2014).

- Upper San Pedro Partnership MISSION & GOALS. Available online: http://www.usppartnership.com/press_mission.htm (accessed 16 June 2014).

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2004. Public Law 108-136 Section 321, 2003.

- Farrell, A.; Hart, M. What does sustainability really mean? The search for useful indicators. Environment 1998, 40, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, W.; Reilly, T.E.; Franke, O.L. Sustainability of ground-water resources. In USGS Circular 1186; USGS Information Services: Reston, VA, USA, 1999; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Water Management of the Regional Aquifer in the Sierra Vista Subwatershed, Arizona—2004 Report to Congress; U.S. Department of Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 36.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Water Management of the Regional Aquifer in the Sierra Vista Subwatershed, Arizona—2012 Report to Congress; U.S. Department of Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; p. 18.

- Costanza, R.; Folke, C. Valuing ecosystem services with efficiency, fairness, and sustainability as goals. In Natures Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Daily, G.C., Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, H.; Goodrich, D.C.; Browning-Aiken, A.; Varady, R.G. Integrating science and policy for water management. In Ecology and Conservation of the San Pedro River; Stromberg, J.C., Tellman, B.J., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2009; pp. 388–406. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, H. Participatory learning on the San Pedro: Designing the crystal ball together. Southwest Hydrol. 2006, 5, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Browning-Aiken, A.; Lansey, K.; Finan, T.; Valdés, J.B. Increasing social-ecological resilience by placing science at the decision table: The role of the San Pedro Basin (Arizona) decision-support system model. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, art.37. [Google Scholar]

- Lacher, L.J.; Turner, D.S.; Gungle, B.; Bushman, B.M.; Richter, H.E. Application of hydrologic tools and monitoring to support managed aquifer recharge decision making in the upper San Pedro River, Arizona, USA. Water 2014. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Fluid Solutions and BBC Research and Consulting. Preliminary Cost/Benefit Analysis for Water Conservation, Reclamation, and Augmentation Alternatives for the Sierra Vista Subwatershed; Prepared for the Upper San Pedro Partnership c/o City of Sierra Vista, Office of Purchasing Manager: Sierra Vista, AR, USA, November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, P.M.; Leake, S.A. Streamflow depletion in wells-understanding and managing the effects of groundwater pumping on streamflow. In USGS Circular 1376; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2012; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg, J.C.; Bagsted, K.J.; Leenhouts, J.M.; Lite, S.J.; Making, E. Effects of stream flow intermittency on riparian vegetation of a semiarid region river (San Pedro River, Arizona). River Res. Appl. 2005, 21, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, J.C.; Lite, S.J.; Dixon, M.; Rychener, T.; Makings, E. Relations between streamflow regime and riparian vegetation composition, structure, and diversity within the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona. In Hydrologic Requirements of and Consumptive Ground-Water Use by Riparian Vegetation along the San Pedro River, Arizona; Leenhouts, J.M., Stromberg, J.C., Scott, R.L., Eds.; U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5163; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2006; pp. 57–106. [Google Scholar]

- Poff, B.; Koestner, K.A.; Neary, D.G.; Henderson, V. Threats to riparian ecosystems in western North America: An analysis of existing literature. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2011, 47, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paretti, N. U.S. Geological Survey. Personal communication, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. A critical review of groundwater budget myth, safe yield and sustainability. J. Hydrol. 2009, 370, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Vrba, J.; Hirata, R.; Girman, J.; Haie, N.; Lipponen, A.; Neupane, B.; Shah, T.; Wallin, B. Groundwater resources sustainability indicators. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Groundwater Sustainability (ISGWAS), The University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 24–27 January 2006; pp. 33–55.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Biological and Conference Opinion for Ongoing and Future Military Operations and Activities at Fort Huachuca, Arizona; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Lacher, L.J. Simulated Groundwater and Surface Water Conditions in the Upper San Pedro Basin, 1902–2105, Preliminary Baseline Results; Task 1 Report prepared for the Friends of the San Pedro River; Lacher Hydrological Consulting: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2011; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Lacher, L.J. Simulated Near-Stream Recharge at Three Sites in the Sierra Vista Subbasin, Arizona; Tasks 2–4 Report for December 2010 Contract, Prepared for Friends of the San Pedro River; Lacher Hydrological Consulting: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2012; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Leake, S.A.; Pool, D.R.; Leenhouts, J.M. Simulated Effects of Ground-Water Withdrawals and Artificial Recharge on Discharge to Streams, Springs, and Riparian Vegetation in the Sierra Vista Subwatershed of the Upper San Pedro Basin, Southeastern Arizona (ver. 1.1, April 2014); U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5207; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2008; p. 14.

- Caves, J.K.; Bodner, G.S.; Simms, K.; Fisher, L.A.; Robertson, T. Integrating collaboration, adaptive management, and scenario-planning: Experiences at Las Cienegas National Conservation Area. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, art.43. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).