The Molecular Basis of Retinal Dystrophies in Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

3. Results

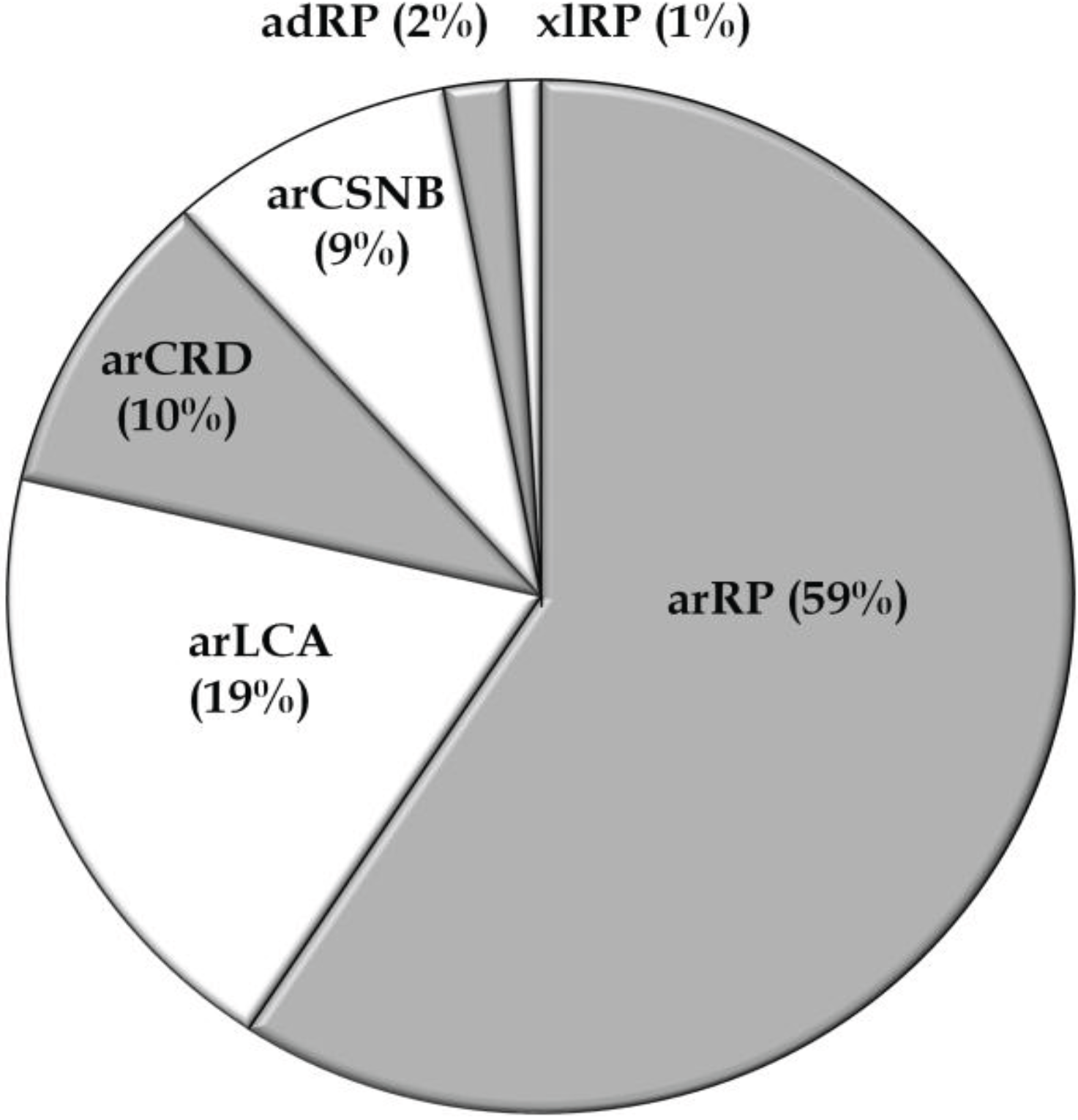

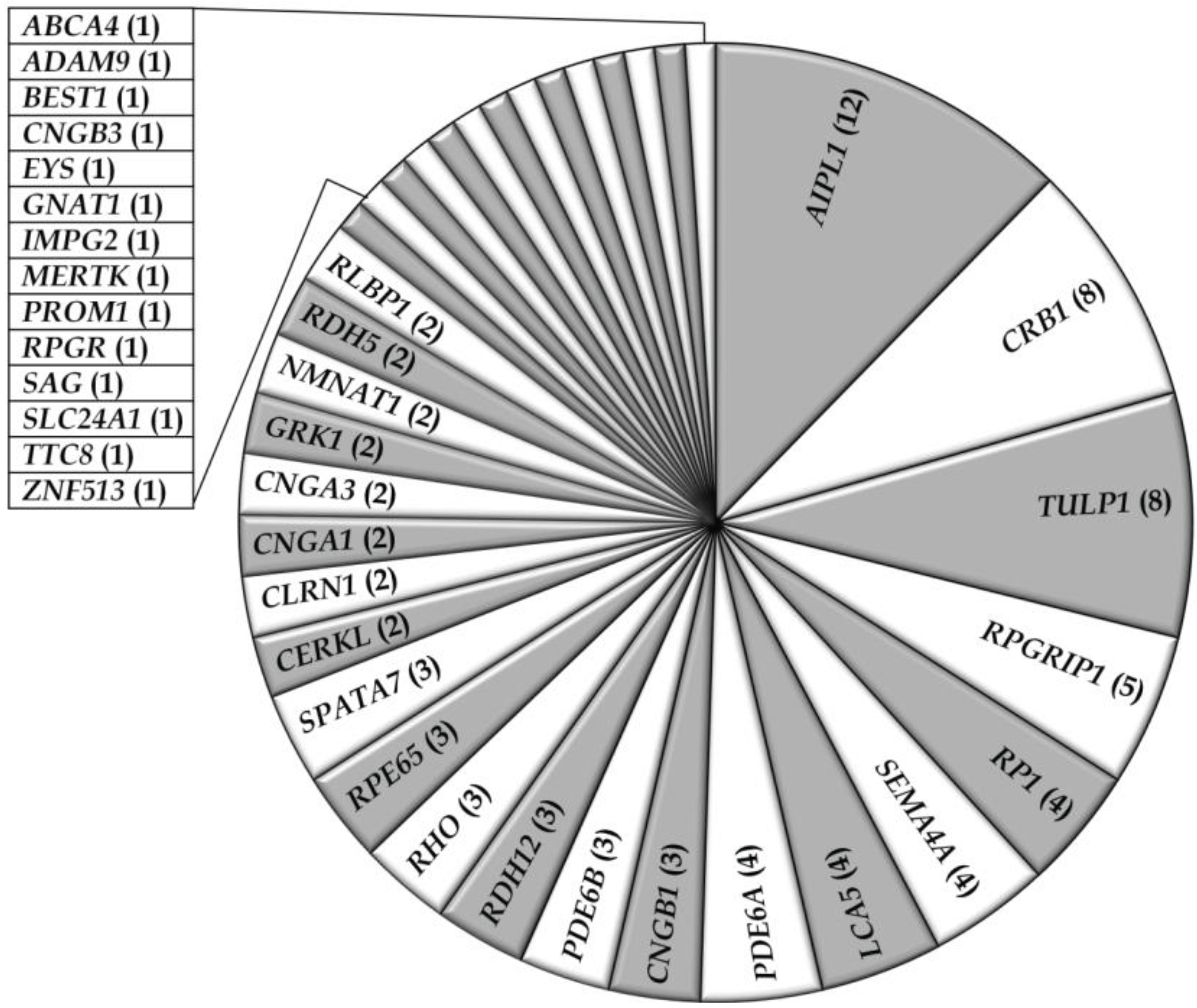

3.1. Overview of Molecular Genetic Studies in Non-Syndromic RD in Pakistan

| Gene | RefSeq Id | Nucleotide variant | Protein variant | Phenotype | # Families | # Patients | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA4 | NM_000350.2 | c.6658C>T | p.(Gln2220*) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [28,29] |

| ADAM9 | NM_003816.2 | c.766C>T | p.(Arg256*) | arCRD | 1 | 4 | [30] |

| AIPL1 ‡ | NM_201253.2 | c.116C>A | p.(Thr39Asp) | arLCA | 1 | 6 | [31] |

| AIPL1 ‡ | NM_014336.3 | c.834G>A | p.(Trp278*) | EORP | 11 | 25 | [29,31,32,33,34] |

| BEST1 ‡ | NM_001139443.1 | c.418C>G | p.(Leu140Val) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [35] |

| CERKL | NM_001030311.2 | c.316C>A | p.(Arg106Ser) | arRP | 1 | 3 | [36] |

| CERKL | NM_001030311.2 | c.847C>T | p.(Arg283*) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [29,37,38] |

| CLRN1 † | NM_001195794.1 | c.92C>T | p.(Pro31Leu) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [39] |

| CLRN1 † | NM_001195794.1 | c.461T>G | p.(Leu154Trp) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [39] |

| CNGA1 | NM_00142564.1 | c.626_627del | p.(Ile209Serfs*26) | arRP | 1 | 7 | [40] |

| CNGA1 | NM_00142564.1 | c.1298G>A | P.(Gly433Asp) | arRP | 1 | 3 | [41] |

| CNGA3 | NM_001298.2 | c.822G>T | p.(Arg274Ser) | arCRD (ACHM) | 1 | 4 | [42] |

| CNGA3 | NM_001298.2 | c.827A>G | p.(Asn276Ser) | arCRD (ACHM) | 1 | 6 | [43] |

| CNGB1 | NM_001297.4 | c.412-1G>A | p.(?) | arRP | 1 | 10 | [44] |

| CNGB1 | NM_001297.4 | c.2284C>T | p.(Arg762Cys) | arRP | 1 | 5 | [44] |

| CNGB1 | NM_001297.4 | c.2493-2A>G | p.(?) | arRP | 1 | 10 | [41] |

| CNGB3 | NM_019098.4 | c.1825del | p.(Val609Trpfs*9) | arCRD (ACHM) | 1 | 2 | [42] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.107C>G | p.(Ser36*) | arLCA | 1 | 10 | [33] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.2234C>T | p.(Thr745Met) | arRP | 1 | 2 | [41,45] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.2536G>A | p.(Gly846Arg) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [31] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.3101T>C | p.(Leu989Thr) | arLCA | 1 | 8 | [31] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.3296C>A | p.(Thr1099Lys) | arRP | 1 | 9 | [44] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.3343_3352del | p.(Gly1115Ilefs*23) | arRP | 1 | 9 | [46] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.3347T>C | p.(Leu1071Pro) | arRP | 1 | 7 | [31] |

| CRB1 | NM_201253.2 | c.3962G>C | p.(Cys1321Ser) | arRP | 1 | 5 | [46] |

| EYS | NM_001142800.1 | c.8299G>T | p.(Asp2767Tyr) | arRP | 1 | 7 | [47] |

| GNAT1 | NM_144499.2 | c.386A>G | p.(Asp129Gly) | arCSNB | 1 | 1 | [48] |

| GRK1 | NM_ 002929 | c.614C>A | p.(Ser205*) | arCSNB (Oguchi) | 1 | 9 | [49] |

| GRK1 | NM_ 002929 | c.827+623_883del | p.(?) | arCSNB (Oguchi) | 1 | 3 | [50] |

| IMPG2 ‡ | NM_016247.3 | c.1680T>A | p.(Tyr560*) | arRP | 1 | 2 | [51] |

| LCA5 ‡ | NM_181714.3 | c.643del | p.(Leu215Tyrfs*11) | arLCA | 1 | 4 | [52] |

| LCA5 ‡ | NM_181714.3 | c.1151del | p.(Pro384Glnfs*17) | arLCA | 3 | 13 | [33,53] |

| MERTK | NM_00634.2 | c.718G>T | p.(Glu240*) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [54] |

| NMNAT1 ‡ | NM_022787.3 | c.25G>A | p.(Val9Met) | arLCA | 1 | 5 | [55] |

| NMNAT1 ‡ | NM_022787.3 | c.838T>C | p.*280Glnext*16 | arLCA | 1 | 8 | [56] |

| PDE6A | NM_000440.2 | c.889C>T | p.(Gly297Ser) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [57] |

| PDE6A | NM_000440.2 | c.1264-2A>G | p.(?) | arRP | 1 | 5 | [57] |

| PDE6A | NM_000440.2 | c.1630C>T | p.(Arg544Trp) | arRP | 1 | 3 | [29] |

| PDE6A | NM_000440.2 | c.2218_2219insT | p.(Ala740Valfs*2) | arRP | 1 | 3 | [57] |

| PDE6B | NM_000283.3 | c.1160C>T | p.(Pro387Leu) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [58] |

| PDE6B | NM_000283.3 | c.1655G>A | p.(Arg552Gln) | arRP | 1 | 9 | [58] |

| PDE6B | NM_000283.3 | c.1722+1G>A | p.(?) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [44] |

| PROM1 | NM_006017.2 | c.1726C>T | p.(Gln576*) | arRP | 1 | 6 | [59] |

| RDH12 | NM_152443.2 | c.506G>A | p.(Arg169Gln) | arLCA/EORD | 2 | 2 | [60] |

| RDH12 | NM_152443.2 | c.619A>G | p.(Asn207Asp) | arLCA/EORD | 1 | 1 | [60] |

| RDH5 | NM_001199771.1 | c.758T>G | p.(Met253Arg) | arCSNB (FA) | 1 | 6 | [61] |

| RDH5 | NM_001199771.1 | c.913_917del | p.(Val305Hisfs*29) | arCSNB (FA) | 1 | 2 | [61] |

| RHO | NM_000539.3 | c.448G>A | p.(Glu150Lys) | arRP | 2 | 6 | [62] |

| RHO | NM_000539.3 | c.1045T>G | p.(*349Gluext*52) | adRP | 1 | 8 | [26] |

| RLBP1 | NM_000326.4 | c.346G>C | p.(Gly116Arg) | FA | 1 | 4 | [63] |

| RLBP1 | NM_000326.4 | c.466C>T | p.(Arg156*) | FA | 1 | 6 | [63] |

| RP1 | NM_006269.1 | c.1458_1461dup | p.(Glu488*) | arRP | 2 | 9 | [64,65] |

| RP1 | NM_006269.1 | c.4555del | p.(Arg1519Glufs*2) | arRP | 1 | 5 | [65] |

| RP1 | NM_006269.1 | c.5252del | p.(Asn1751Ilefs*4) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [65] |

| RPE65 | NM_000329.2 | c.131G>A | p.(Arg44Gln) | EORP | 1 | 3 | [41,66,67] |

| RPE65 | NM_000329.2 | c.361del | p.(Ser121Leufs*6) | EORP | 1 | 4 | [41,67] |

| RPE65 | NM_000329.2 | c.751G>T | p.(Val251Phe) | arLCA | 1 | 6 | [33] |

| RPGR | NM_001034853.1 | c.2426_2427del | p.(Glu809Glyfs*25) | xlRP | 1 | 8 | [41,68] |

| RPGRIP1 | NM_020366.3 | c.587+1G>C | p.(?) | arLCA | 1 | 1 | [33] |

| RPGRIP1 | NM_020366.3 | c.1180C>T | p.(Gln394*) | arLCA | 1 | 1 | [33] |

| RPGRIP1 | NM_020366.3 | c.2480G>T | p.(Arg827Leu) | arCRD, arLCA | 2 | 9 | [33,69] |

| RPGRIP1 | NM_020366.3 | c.3620T>G | p.(Leu1207*) | arLCA | 1 | 1 | [33] |

| SAG | NM_000541.4 | c.916G>T | p.(Glu306*) | arCSNB | 1 | 1 | [70] |

| SEMA4A ‡ | NM_022367.3 | c.1033G>C | p.(Asp345His) | arCRD, arRP | 4 | 4 | [27] |

| SEMA4A ‡ | NM_022367.3 | c.1049T>G | p.(Phe350Cys) | ||||

| SLC24A1 ‡ | NM_004727.2 | c.1613_1614del | p.(Phe538Cysfs*23) | arCSNB | 1 | 5 | [71] |

| SPATA7 | NM_018418.4 | c.253C>T | p.(Arg85*) | arLCA/arRD | 2 | 3 | [72] |

| SPATA7 | NM_018418.4 | c.960dup | p.(Pro321Thrfs*6) | arLCA/arRD | 1 | 6 | [72,73] |

| TTC8 † | NM_144596.2 | c.115-2A>G | p.(?) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [74] |

| TULP1 | NM_003322.3 | c.1138A>G | p.(Thr380Ala) | arRP | 3 | 34 | [33,75,76] |

| TULP1 | NM_003322.3 | c.1445G>A | p.(Arg482Gln) | arRP | 1 | 8 | [75] |

| TULP1 | NM_003322.3 | c.1466A>G | p.(Lys489Arg) | arRP | 4 | 19 | [41,76,77] |

| ZNF513 | NM_144631.5 | c.1015T>C | p.(Cys339Arg) | arRP | 1 | 4 | [78,79] |

| Gene | RefSeq Id | Nucleotide variant | Protein variant | Phenotype | # Families | # Patients | Ref. | phyloP | Grantham distance | PolyPhen | SIFT | EVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP1 | NM_006269.1 | c.1118C>T | p.(Thr373Ile) | arRP | 2 | 11 | [64] | 0.61 | 89 | Benign (0.01) | Tolerated (0.50) | T = 152; C = 12,854 (rs77775126) |

| RPGRIP1 | NM_020366.3 | c.1639G>T | p.(Ala547Ser) | arCRD | 3 | 12 | [69] | 0.29 | 99 | Probably damaging (1.00) | Tolerated (0.49) | T = 2,792; G = 9,214 (rs10151259) |

| SEMA4A | NM_022367.3 | c.2138G>A | p.(Arg713Gln) | adRP | 1 | 4 | [27] | 1.25 | 43 | Benign (0.23) | Tolerated (0.43) | A = 451; G = 12,555 (rs41265017) |

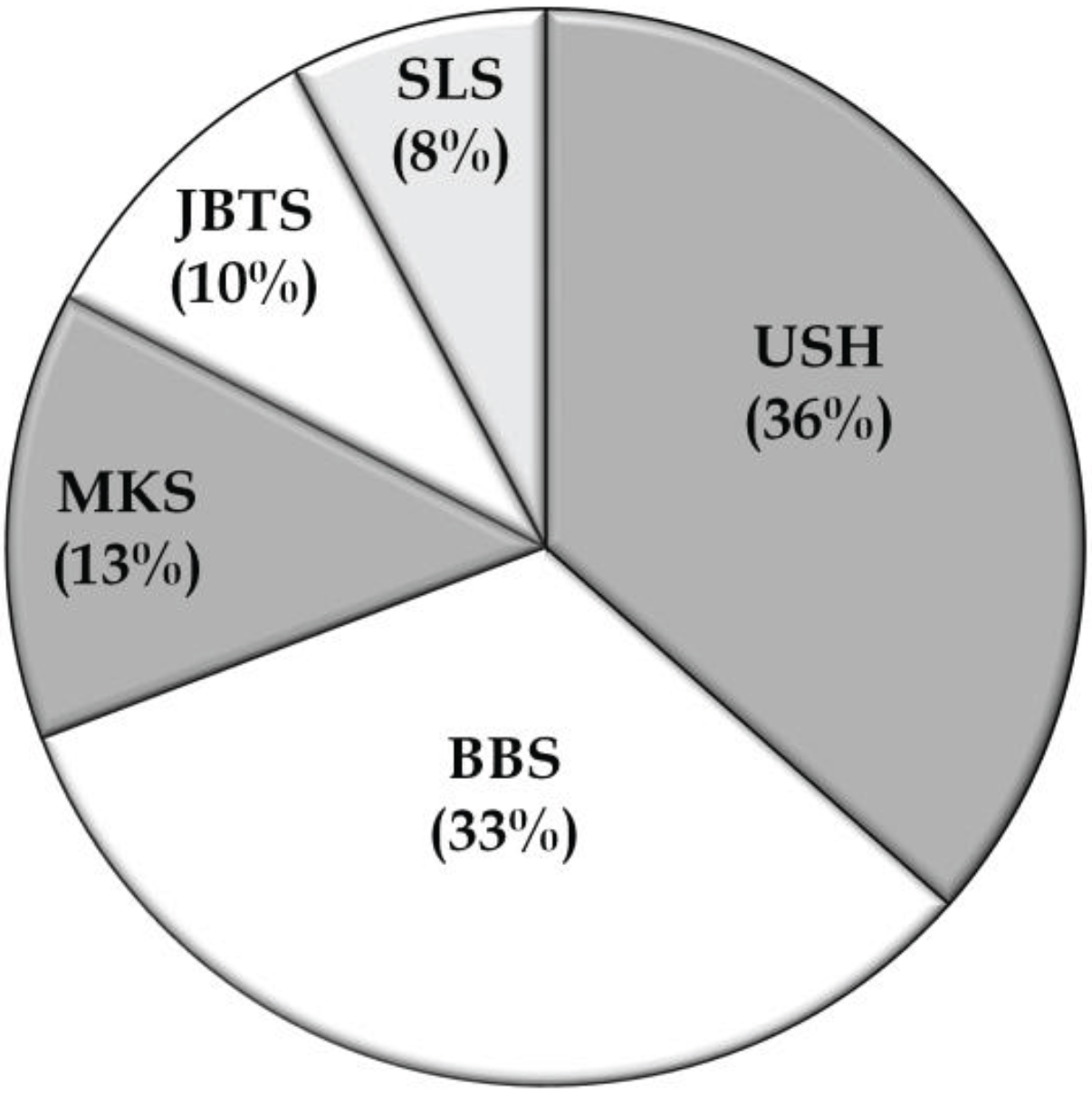

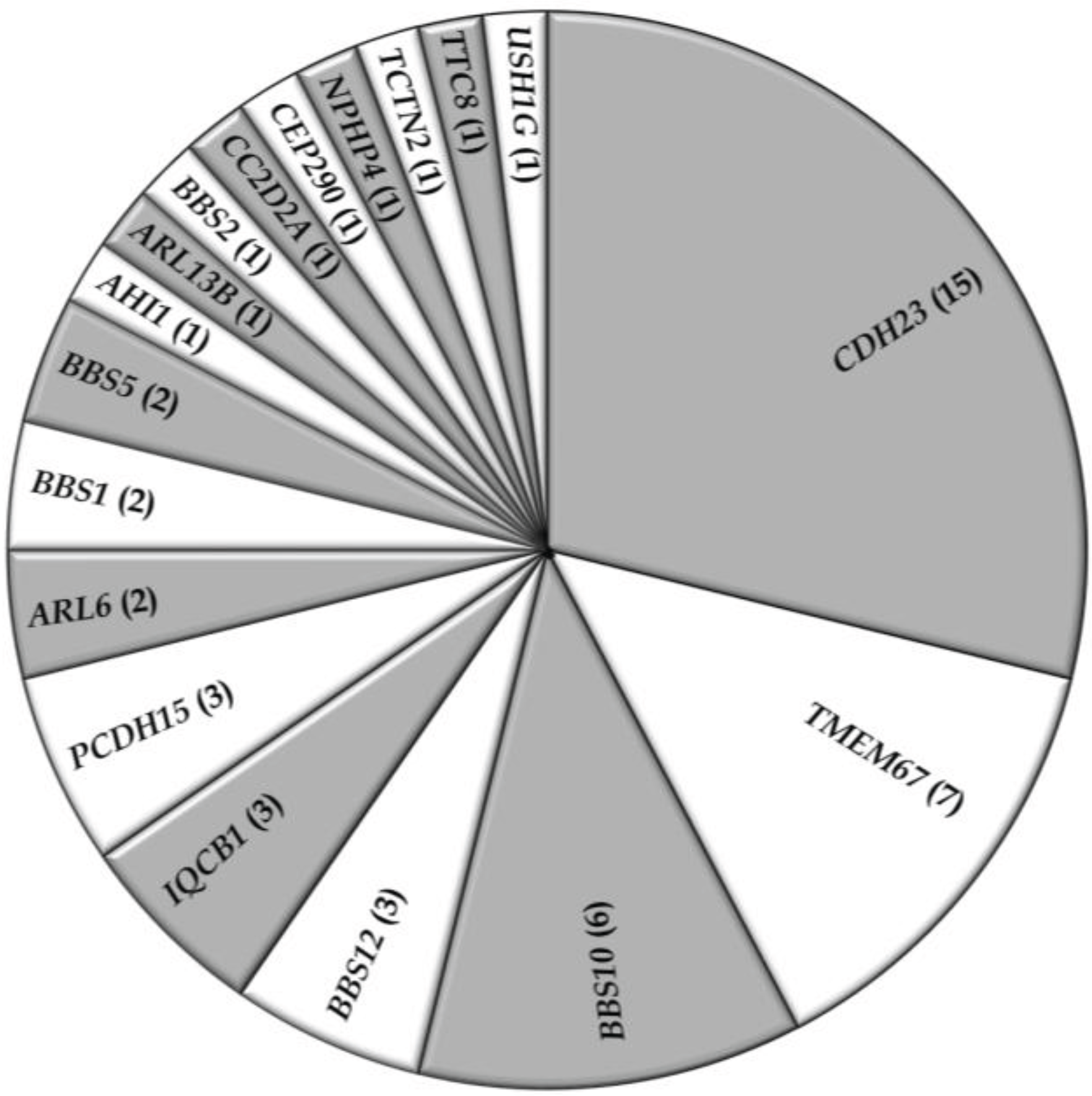

3.2. Overview of Molecular Genetic Studies in Syndromic RDs in Pakistan

4. Discussion

| Gene | RefSeq Id | Nucleotide variant | Protein variant | Phenotype | # Families | # Patients | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI1 | NM_017651.4 | c.2370dup | p.(Lys791*) | arJBTS | 1 | 2 | [90] |

| ARL6 | NM_032146.3 | c.281T>C | p.(Ile94Thr) | arBBS | 1 | 5 | [91] |

| ARL6 | NM_032146.3 | c.123+1119del | p.(?) | arBBS | 1 | 1 | [92] |

| ARL13B | NM_182896.2 | c.236G>A | p.(Arg79Gln) | arJBTS | 1 | 3 | [93] |

| BBS1 | NM_02464.9.4 | c.47+1G>T | p.(?) | arBBS | 1 | 2 | [94] |

| BBS1 | NM_02464.9.4 | c.442G>A | p.(Asp148Asn) | arBBS | 1 | 2 | [94] |

| BBS2 | NM_031885.3 | c.1237C>T | p.(Arg413*) | arBBS | 1 | 1 | [95] |

| BBS5 | NM_152384.2 | c.2T>A | p.(Met1Lys) | arBBS | 2 | 2 | [95] |

| BBS10 | NM_024685.3 | c.271dup | p.(Cys91Leufs*5) | arBBS | 2 | 4 | [96] |

| BBS10 | NM_024685.3 | c.1075C>T | p.(Gln359*) | arBBS | 1 | 7 | [91] |

| BBS10 | NM_024685.3 | c.1091del | p.(Asn364Thrfs*5) | arBBS | 1 | 1 | [96] |

| BBS10 | NM_024685.3 | c.1958_1967del | p.(Ser653Ilefs*4) | arBBS | 1 | 2 | [97] |

| BBS10 | NM_024685.3 | c.2121dup | p.(Lys708*) | arBBS | 1 | 1 | [96] |

| BBS12 | NM_152618.2 | c.1589T>C | p.(Leu530Pro) | arBBS | 2 | 2 | [95] |

| BBS12 | NM_152618.2 | c.2102C>A | p.(Ser701*) | arBBS | 1 | 3 | [98] |

| CC2D2A ‡ | NM_001080522.2 | c.2003+1G>C | p.(?) | arJBTS | 1 | 5 | [82] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.1114C>T | p.(Gln372*) | arUSH1 | 1 | 3 | [83] |

| CDH23 | NM_022124.5 | c.2587+1G>A | p.(?) | arUSH1 | 1 | 4 | [99] |

| CDH23 | NI | NI | p.(Arg1305*) | arUSH1 | 1 | 4 | [99] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.3106_3106+11delinsTGGT | p.(Gly1036delinsTrpCys) | arUSH1 | 1 | 5 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.6050-9G>A | p.(?) | arUSH1 | 4 | 13 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.6050-1G>C | p.(?) | arUSH1 | 1 | 6 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.6054_6074del | p.(Val2019_Val2025del) | arUSH1 | 1 | 3 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.6845del | p.(Asn2282Thrfs*91) | arUSH1 | 1 | 3 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.7198C>T | p.(Pro2400Ser) | arUSH1 | 1 | 4 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.8150A>G | p.(Asp2717Gly) | arUSH1 | 1 | 3 | [83] |

| CDH23 ‡ | NM_022124.5 | c.8208_8209del | p.(Val2737Alafs*2) | arUSH1 | 2 | 11 | [83] |

| CEP290 | NM_025114.3 | c.5668G>T | p.(Gly1890*) | arJBTS | 1 | 1 | [100,83] |

| IQCB1 | NM_001023570.2 | c.488-1G>A | p.(?) | arSLSN | 1 | 1 | [41,102] |

| IQCB1 | NM_001023570.2 | c.1465C>T | p.(Arg489*) | arSLSN | 1 | 1 | [102] |

| IQCB1 | NM_001023570.2 | c.1796T>G | p.(*599Serext*2) | arSLSN | 1 | 1 | [102] |

| NPHP4 | NM_015102.3 | c.3272dup | p.(Ser1092Valfs*11) | arSLSN | 1 | 1 | [102] |

| PCDH15 ‡ | NM_001142763.1 | c.7C>T | p.(Arg3*) | arUSH1 | 1 | 5 | [84] |

| PCDH15 ‡ | NM_001142763.1 | c.1927C>T | p.(Arg643*) | arUSH1 | 1 | 3 | [103] |

| PCDH15 ‡ | NM_001142763.1 | c.3389-2A>G | p.(?) | arUSH1 | 1 | 3 | [84] |

| TCTN2 | NM_024809.3 | c.1873C>T | p.(Gln625*) | arJBTS | 1 | 4 | [104] |

| TMEM67 | NM_153704.5 | c.647del | p.(Val217Leufs*5) | arMKS | 1 | 2 | [105] |

| TMEM67 | NM_153704.5 | c.715-2A>G | p.(?) | arMKS | 1 | 1 | [105] |

| TMEM67 | NM_153704.5 | c.1127A>C | p.(Gln376Pro) | arMKS | 2 | 2 | [105] |

| TMEM67 | NM_153704.5 | c.1575+1G>A | p.(?) | arMKS | 3 | 5 | [105] |

| TTC8 | NM_144596.2 | c.1049+2_1049+4del | p.(?) | arBBS | 1 | 3 | [106] |

| USH1G | NM_173477.2 | c.163_164+13del | p.(Gly56*) | arUSH1 | 1 | 4 | [107] |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berger, W.; Kloeckener-Gruissem, B.; Neidhardt, J. The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010, 29, 335–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, P.; Moore, A.T. Molecular genetics of infantile-onset retinal dystrophies. Eye 2007, 21, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, A.I.; Black, A.; Bennett, J.; Cremers, F.P.M. Lighting a candle in the dark: Advances in genetics and gene therapy of recessive retinal dystrophies. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 3042–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiners, J.; Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; Jurgens, K.; Marker, T.; Wolfrum, U. Molecular basis of human usher syndrome: Deciphering the meshes of the usher protein network provides insights into the pathomechanisms of the usher disease. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 83, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Zhou, W. Nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 1855–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Benzing, T.; Katsanis, N. Ciliopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, A.G.; Michaelides, M.; Saihan, Z.; Bird, A.C.; Webster, A.R.; Moore, A.T.; Fitzke, F.W.; Holder, G.E. Functional characteristics of patients with retinal dystrophy that manifest abnormal parafoveal annuli of high density fundus autofluorescence; a review and update. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2008, 116, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, M. On the heredity of retinitis pigmentosa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1982, 66, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, C.; Millan, J.M. Retinitis pigmentosa and allied conditions today: A paradigm of translational research. Genome Med. 2010, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhi, M.I.; Ahmed, J. Frequency and clinical presentation of retinal dystrophies—A hospital based study. Pak. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 18, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bittles, A.H. Endogamy, consanguinity and community disease profiles. Community Genet. 2005, 8, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittles, A. Consanguinity and its relevance to clinical genetics. Clin. Genet. 2001, 60, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, E.S.; Botstein, D. Homozygosity mapping: A way to map human recessive traits with the DNA of inbred children. Science 1987, 236, 1567–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.G.; Cox, J.; Springell, K.; Hampshire, D.J.; Mohamed, M.D.; McKibbin, M.; Stern, R.; Raymond, F.L.; Sandford, R.; Malik Sharif, S.; et al. Quantification of homozygosity in consanguineous individuals with autosomal recessive disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 78, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retinal Information Network. Available online: https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/ (accessed on 2 August 2013).

- Estrada-Cuzcano, A.; Roepman, R.; Cremers, F.P.M.; den Hollander, A.I.; Mans, D.A. Non-syndromic retinal ciliopathies: Translating gene discovery into therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, R111–R124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, K.; Zacks, D.N.; Caruso, R.; Karoukis, A.J.; Branham, K.; Yashar, B.M.; Haimann, M.H.; Trzupek, K.; Meltzer, M.; Blain, D.; et al. Molecular testing for hereditary retinal disease as part of clinical care. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2007, 125, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenekoop, R.K.; Lopez, I.; den Hollander, A.I.; Allikmets, R.; Cremers, F.P.M. Genetic testing for retinal dystrophies and dysfunctions: Benefits, dilemmas and solutions. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2007, 35, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.P.; Macdonald, I.M.; Tumminia, S.J.; Smaoui, N.; Blain, D.; Nezhuvingal, A.A.; Sieving, P.A. National Ophthalmic Disease Genotyping, N. Genomics in the era of molecular ophthalmology: Reflections on the national ophthalmic disease genotyping network (eyegene). Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008, 126, 424–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Biotechnology information. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ (accessed on 21 November 2013).

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Available online: http://www.omim.org/ (accessed on 21 November 2013).

- The Human Gene Mutation Database. Available online: http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php/ (accessed on 13 May 2013).

- Adzhubei, I.A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V.E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Henikoff, S.; Ng, P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the sift algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Available online: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ (accessed on 1 July 2013).

- Bessant, D.A.; Khaliq, S.; Hameed, A.; Anwar, K.; Payne, A.M.; Mehdi, S.Q.; Bhattacharya, S.S. Severe autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa caused by a novel rhodopsin mutation (Ter349Glu). Mutations in brief no. 208. Online. Hum. Mutat. 1999, 13, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, A.; Ismail, M.; Mehdi, S.Q.; Khaliq, S. Identification of novel mutations in the SEMA4A gene associated with retinal degenerative diseases. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 43, 378–381. [Google Scholar]

- Maugeri, A.; Klevering, B.J.; Rohrschneider, K.; Blankenagel, A.; Brunner, H.G.; Deutman, A.F.; Hoyng, C.B.; Cremers, F.P.M. Mutations in the ABCA4 (ABCR) gene are the major cause of autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Ajmal, M.; Micheal, S.; Azam, M.; Hussain, A.; Shahzad, A.; Venselaar, H.; Bokhari, H.; de Wijs, I.; Hoefsloot, L.; et al. Homozygosity mapping identifies genetic defects in four consanguineous families with retinal dystrophy from pakistan. Clin. Genet. 2013, 84, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, D.A.; Toomes, C.; Bida, L.; Danciger, M.; Towns, K.V.; McKibbin, M.; Jacobson, S.G.; Logan, C.V.; Ali, M.; Bond, J.; et al. Loss of the metalloprotease ADAM9 leads to cone-rod dystrophy in humans and retinal degeneration in mice. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, S.; Abid, A.; Hameed, A.; Anwar, K.; Mohyuddin, A.; Azmat, Z.; Shami, S.A.; Ismail, M.; Mehdi, S.Q. Mutation screening of Pakistani families with congenital eye disorders. Exp. Eye Res. 2003, 76, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damji, K.F.; Sohocki, M.M.; Khan, R.; Gupta, S.K.; Rahim, M.; Loyer, M.; Hussein, N.; Karim, N.; Ladak, S.S.; Jamal, A.; et al. Leber’s congenital amaurosis with anterior keratoconus in pakistani families is caused by the Trp278X mutation in the AIPL1 gene on 17p. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 36, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin, M.; Ali, M.; Mohamed, M.D.; Booth, A.P.; Bishop, F.; Pal, B.; Springell, K.; Raashid, Y.; Jafri, H.; Inglehearn, C.F. Genotype-phenotype correlation for leber congenital amaurosis in Northern Pakistan. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohocki, M.M.; Bowne, S.J.; Sullivan, L.S.; Blackshaw, S.; Cepko, C.L.; Payne, A.M.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Khaliq, S.; Mehdi, S.Q.; Birch, D.G.; et al. Mutations in a new photoreceptor-pineal gene on 17p cause leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 2000, 24, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.E.; Millar, I.D.; Urquhart, J.E.; Burgess-Mullan, R.; Shweikh, Y.; Parry, N.; O’Sullivan, J.; Maher, G.J.; McKibbin, M.; Downes, S.M.; et al. Missense mutations in a retinal pigment epithelium protein, bestrophin-1, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 85, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ramprasad, V.L.; Soumittra, N.; Mohamed, M.D.; Jafri, H.; Rashid, Y.; Danciger, M.; McKibbin, M.; Kumaramanickavel, G.; Inglehearn, C.F. A missense mutation in the nuclear localization signal sequence of CERKL (p.R106S) causes autosomal recessive retinal degeneration. Mol. Vis. 2008, 14, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Littink, K.W.; Koenekoop, R.K.; van den Born, L.I.; Collin, R.W.J.; Moruz, L.; Veltman, J.A.; Roosing, S.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Omar, A.; Darvish, M.; et al. Homozygosity mapping in patients with cone-rod dystrophy: Novel mutations and clinical characterizations. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 5943–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Fernandez, A.; Riveiro-Alvarez, R.; Vallespin, E.; Wilke, R.; Tapias, I.; Cantalapiedra, D.; Aguirre-Lamban, J.; Gimenez, A.; Trujillo-Tiebas, M.J.; Ayuso, C. CERKL mutations and associated phenotypes in seven spanish families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 2709–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Kersten, F.F.; Azam, M.; Collin, R.W.J.; Hussain, A.; Shah, S.T.A.; Keunen, J.E.E.; Kremer, H.; Cremers, F.P.M.; Qamar, R.; et al. CLRN1 mutations cause nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zulfiqar, F.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Xiao, X.; Ahmad, Z.; Riazuddin, S.; Hejtmancik, J.F. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa in a Pakistani family mapped to CNGA1 with identification of a novel mutation. Mol. Vis. 2004, 10, 884–889. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmal, M.; COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan, and Department of Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Personal Communications, 2014.

- Azam, M.; Collin, R.W.J.; Shah, S.T.A.; Shah, A.A.; Khan, M.I.; Hussain, A.; Sadeque, A.; Strom, T.M.; Thiadens, A.A.H.J.; Roosing, S.; et al. Novel CNGA3 and CNGB3 mutations in two Pakistani families with achromatopsia. Mol. Vis. 2010, 16, 774–781. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, M.A.; Awan, B.M.; Sarfraz, M.; Khan, M.N.; Rashid, S.; Ansar, M. Genetic analysis of four Pakistani families with achromatopsia and a novel S4 motif mutation of CNGA3. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 55, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Collin, R.W.J.; Malik, A.; Khan, M.I.; Shah, S.T.A.; Shah, A.A.; Hussain, A.; Sadeque, A.; Arimadyo, K.; Ajmal, M.; et al. Identification of novel mutations in pakistani families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 1377–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, A.I.; ten Brink, J.B.; de Kok, Y.J.M.; van Soest, S.; van den Born, L.I.; van Driel, M.A.; van de Pol, T.J.R.; Payne, A.M.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Kellner, U.; et al. Mutations in a human homologue of Drosophila crumbs cause retinitis pigmentosa (RP12). Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotery, A.J.; Malik, A.; Shami, S.A.; Sindhi, M.; Chohan, B.; Maqbool, C.; Moore, P.A.; Denton, M.J.; Stone, E.M. CRB1 mutations may result in retinitis pigmentosa without para-arteriolar RPE preservation. Ophthalmic Genet. 2001, 22, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Collin, R.W.J.; Arimadyo, K.; Micheal, S.; Azam, M.; Qureshi, N.; Faradz, S.M.H.; den Hollander, A.I.; Qamar, R.; Cremers, F.P.M. Missense mutations at homologous positions in the fourth and fifth laminin A G-like domains of eyes shut homolog cause autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Vis. 2010, 16, 2753–2759. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.A.; Chavali, V.R.; Ali, S.; Iqbal, M.; Riazuddin, S.; Khan, S.N.; Husnain, T.; Sieving, P.A.; Ayyagari, R.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; et al. GNAT1 associated with autosomal recessive congenital stationary night blindness. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Collin, R.W.J.; Khan, M.I.; Shah, S.T.A.; Qureshi, N.; Ajmal, M.; den Hollander, A.I.; Qamar, R.; Cremers, F.P.M. A novel mutation in GRK1 causes oguchi disease in a consanguineous Pakistani family. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 1788–1793. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zulfiqar, F.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Xiao, X.; Yasmeen, A.; Rogan, P.K.; Caruso, R.; Sieving, P.A.; Riazuddin, S.; Hejtmancik, J.F. A variant form of Oguchi disease mapped to 13q34 associated with partial deletion of GRK1 gene. Mol. Vis. 2005, 11, 977–985. [Google Scholar]

- Bandah-Rozenfeld, D.; Collin, R.W.J.; Banin, E.; van den Born, L.I.; Coene, K.L.M.; Siemiatkowska, A.M.; Zelinger, L.; Khan, M.I.; Lefeber, D.J.; Erdinest, I.; et al. Mutations in IMPG2, encoding interphotoreceptor matrix proteoglycan 2, cause autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Daud, S.; Kakar, N.; Nurnberg, G.; Nurnberg, P.; Babar, M.E.; Thoenes, M.; Kubisch, C.; Ahmad, J.; Bolz, H.J. Identification of a novel LCA5 mutation in a Pakistani family with Leber congenital amaurosis and cataracts. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 1940–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hollander, A.I.; Koenekoop, R.K.; Mohamed, M.D.; Arts, H.H.; Boldt, K.; Towns, K.V.; Sedmak, T.; Beer, M.; Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; McKibbin, M.; et al. Mutations in LCA5, encoding the ciliary protein lebercilin, cause leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzadi, A.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Ali, S.; Li, D.; Khan, S.N.; Husnain, T.; Akram, J.; Sieving, P.A.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; Riazuddin, S. Nonsense mutation in MERTK causes autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa in a consanguineous Pakistani family. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 94, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.J.; Zhang, Q.; Nakamaru-Ogiso, E.; Kannabiran, C.; Fonseca-Kelly, Z.; Chakarova, C.; Audo, I.; Mackay, D.S.; Zeitz, C.; Borman, A.D.; et al. NMNAT1 mutations cause leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenekoop, R.K.; Wang, H.; Majewski, J.; Wang, X.; Lopez, I.; Ren, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Fishman, G.A.; Genead, M.; et al. Mutations in NMNAT1 cause leber congenital amaurosis and identify a new disease pathway for retinal degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazuddin, S.A.; Zulfiqar, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, W.; Li, S.; Jiao, X.; Shahzadi, A.; Amer, M.; Iqbal, M.; Hussnain, T.; et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the alpha-subunit of rod phosphodiesterase in consanguineous Pakistani families. Mol. Vis. 2006, 12, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Shahzadi, A.; Nasir, I.A.; Khan, S.N.; Husnain, T.; Akram, J.; Sieving, P.A.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; Riazuddin, S. Mutations in the beta-subunit of rod phosphodiesterase identified in consanguineous Pakistani families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zulfiqar, F.; Xiao, X.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Caruso, R.; MacDonald, I.; Sieving, P.; Riazuddin, S.; Hejtmancik, J.F. Severe retinitis pigmentosa mapped to 4p15 and associated with a novel mutation in the PROM1 gene. Hum. Genet. 2007, 122, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, D.S.; Dev Borman, A.; Moradi, P.; Henderson, R.H.; Li, Z.; Wright, G.A.; Waseem, N.; Gandra, M.; Thompson, D.A.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; et al. RDH12 retinopathy: Novel mutations and phenotypic description. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 2706–2716. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmal, M.; Khan, M.I.; Neveling, K.; Khan, Y.M.; Ali, S.H.; Ahmed, W.; Iqbal, M.S.; Azam, M.; den Hollander, A.I.; Collin, R.W.J.; et al. Novel mutations in RDH5 cause fundus albipunctatus in two consanguineous Pakistani families. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, M.; Khan, M.I.; Gal, A.; Hussain, A.; Shah, S.T.A.; Khan, M.S.; Sadeque, A.; Bokhari, H.; Collin, R.W.J.; Orth, U.; et al. A homozygous p.Glu150Lys mutation in the opsin gene of two pakistani families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 2526–2534. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, S.; Ali, S.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Farooq, T.; Butt, N.H.; Zafar, A.U.; Khan, S.N.; Husnain, T.; Macdonald, I.M.; Sieving, P.A.; et al. Mutations in RLBP1 associated with fundus albipunctatus in consanguineous Pakistani families. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 95, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, S.; Abid, A.; Ismail, M.; Hameed, A.; Mohyuddin, A.; Lall, P.; Aziz, A.; Anwar, K.; Mehdi, S.Q. Novel association of RP1 gene mutations with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. J. Med. Genet. 2005, 42, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazuddin, S.A.; Zulfiqar, F.; Zhang, Q.; Sergeev, Y.V.; Qazi, Z.A.; Husnain, T.; Caruso, R.; Riazuddin, S.; Sieving, P.A.; Hejtmancik, J.F. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa is associated with mutations in RP1 in three consanguineous Pakistani families. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 2264–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simovich, M.J.; Miller, B.; Ezzeldin, H.; Kirkland, B.T.; McLeod, G.; Fulmer, C.; Nathans, J.; Jacobson, S.G.; Pittler, S.J. Four novel mutations in the RPE65 gene in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum. Mutat. 2001, 18, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Coppieters, F.; de Baere, E.; Leroy, B. Development of a next-generation sequencing platform for retinal dystrophies, with LCA and RP as proof of concept. Bull. Soc. Belg. Ophtalmol. 2011, 317, 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort, R.; Lennon, A.; Bird, A.C.; Tulloch, B.; Axton, R.; Miano, M.G.; Meindl, A.; Meitinger, T.; Ciccodicola, A.; Wright, A.F. Mutational hot spot within a new RPGR exon in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Abid, A.; Aziz, A.; Ismail, M.; Mehdi, S.Q.; Khaliq, S. Evidence of rpgrip1 gene mutations associated with recessive cone-rod dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, N.K.; Qavi, A.H.; Malik, S.N.; Maria, M.; Riaz, M.; Cremers, F.P.M.; Azam, M.; Qamar, R. A nonsense mutation in S-antigen (p.Glu306*) causes Oguchi disease. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Riazuddin, S.A.; Shahzadi, A.; Zeitz, C.; Ahmed, Z.M.; Ayyagari, R.; Chavali, V.R.; Ponferrada, V.G.; Audo, I.; Michiels, C.; Lancelot, M.E.; et al. A mutation in SLC24A1 implicated in autosomal-recessive congenital stationary night blindness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, D.S.; Ocaka, L.A.; Borman, A.D.; Sergouniotis, P.I.; Henderson, R.H.; Moradi, P.; Robson, A.G.; Thompson, D.A.; Webster, A.R.; Moore, A.T. Screening of SPATA7 in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis and severe childhood-onset retinal dystrophy reveals disease-causing mutations. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 3032–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; den Hollander, A.I.; Moayedi, Y.; Abulimiti, A.; Li, Y.; Collin, R.W.J.; Hoyng, C.B.; Lopez, I.; Abboud, E.B.; Al-Rajhi, A.A.; et al. Mutations in SPATA7 cause Leber congenital amaurosis and juvenile retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazuddin, S.A.; Iqbal, M.; Wang, Y.; Masuda, T.; Chen, Y.; Bowne, S.; Sullivan, L.S.; Waseem, N.H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Daiger, S.P.; et al. A splice-site mutation in a retina-specific exon of BBS8 causes nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Khan, M.I.; Micheal, S.; Ahmed, W.; Shah, A.; Venselaar, H.; Bokhari, H.; Azam, A.; Waheed, N.K.; Collin, R.W.J.; et al. Identification of recurrent and novel mutations in TULP1 in Pakistani families with early-onset retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 1226–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Naeem, M.A.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Ali, S.; Farooq, T.; Qazi, Z.A.; Khan, S.N.; Husnain, T.; Riazuddin, S.; Sieving, P.A.; et al. Association of pathogenic mutations in TULP1 with retinitis pigmentosa in consanguineous Pakistani families. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Lennon, A.; Li, Y.; Lorenz, B.; Fossarello, M.; North, M.; Gal, A.; Wright, A. Tubby-like protein-1 mutations in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 1998, 351, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Nakaya, N.; Chavali, V.R.; Ma, Z.; Jiao, X.; Sieving, P.A.; Riazuddin, S.; Tomarev, S.I.; Ayyagari, R.; Riazuddin, S.A.; et al. A mutation in ZNF513, a putative regulator of photoreceptor development, causes autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Li, L.; Shahid, M.; Kousar, S.; Sieving, P.A.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; Riazuddin, S. A novel locus for autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa in a consanguineous Pakistani family maps to chromosome 2p. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 149, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.A.; Ansar, M.; Marshall, C.R.; Noor, A.; Shaheen, N.; Mowjoodi, A.; Khan, M.A.; Ali, G.; Amin-ud-Din, M.; Feuk, L.; et al. Mapping of three novel loci for non-syndromic autosomal recessive mental retardation (NS-ARMR) in consanguineous families from pakistan. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, N.; Goebel, I.; Daud, S.; Nurnberg, G.; Agha, N.; Ahmad, A.; Nurnberg, P.; Kubisch, C.; Ahmad, J.; Borck, G. A homozygous splice site mutation in TRAPPC9 causes intellectual disability and microcephaly. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 55, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Windpassinger, C.; Patel, M.; Stachowiak, B.; Mikhailov, A.; Azam, M.; Irfan, M.; Siddiqui, Z.K.; Naeem, F.; Paterson, A.D.; et al. CC2D2A, encoding a coiled-coil and C2 domain protein, causes autosomal-recessive mental retardation with retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.M.; Bhatti, R.; Madeo, A.C.; Turriff, A.; Muskett, J.A.; Zalewski, C.K.; King, K.A.; Ahmed, Z.M.; Riazuddin, S.; Ahmad, N.; et al. Allelic hierarchy of CDH23 mutations causing non-syndromic deafness DFNB12 or usher syndrome USH1D in compound heterozygotes. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 48, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.M.; Riazuddin, S.; Bernstein, S.L.; Ahmed, Z.; Khan, S.; Griffith, A.J.; Morell, R.J.; Friedman, T.B.; Wilcox, E.R. Mutations of the protocadherin gene PCDH15 cause usher syndrome type 1f. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Abid, A.; Anwar, K.; Mehdi, S.Q.; Khaliq, S. Refinement of the locus for autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy (CORD8) linked to chromosome 1q23-q24 in a pakistani family and exclusion of candidate genes. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 51, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Khaliq, S.; Ismail, M.; Anwar, K.; Mehdi, S.Q.; Bessant, D.; Payne, A.M.; Bhattacharya, S.S. A new locus for autosomal recessive RP (RP29) mapping to chromosome 4q32-q34 in a pakistani family. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 1436–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zulfiqar, F.; Xiao, X.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Ayyagari, R.; Sabar, F.; Caruso, R.; Sieving, P.A.; Riazuddin, S.; Hejtmancik, J.F. Severe autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa maps to chromosome 1p13.3-p21.2 between D1S2896 and D1S457 but outside ABCA4. Hum. Genet. 2005, 118, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.M.; Riazuddin, S.; Khan, S.N.; Friedman, P.L.; Riazuddin, S.; Friedman, T.B. USH1H, a novel locus for type I Usher syndrome, maps to chromosome 15q22-23. Clin. Genet. 2009, 75, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworek, T.J.; Bhatti, R.; Latief, N.; Khan, S.N.; Riazuddin, S.; Ahmed, Z.M. USH1K, a novel locus for type I Usher syndrome, maps to chromosome 10p11.21-q21.1. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 57, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsch, B.; Sayer, J.A.; Attanasio, M.; Pereira, R.R.; Eccles, M.; Hennies, H.C.; Otto, E.A.; Hildebrandt, F. Identification of the first AHI1 gene mutations in nephronophthisis-associated Joubert syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006, 21, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ullah, I.; Irfanullah, I.; Touseef, M.; Basit, S.; Khan, M.N.; Ahmad, W. Novel homozygous mutations in the genes ARL6 and BBS10 underlying Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Gene 2013, 515, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Smaoui, N.; Hammer, M.B.; Jiao, X.; Riazuddin, S.A.; Harper, S.; Katsanis, N.; Riazuddin, S.; Chaabouni, H.; Berson, E.L.; et al. Molecular analysis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome families: Report of 21 novel mutations in 10 genes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 5317–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantagrel, V.; Silhavy, J.L.; Bielas, S.L.; Swistun, D.; Marsh, S.E.; Bertrand, J.Y.; Audollent, S.; Attie-Bitach, T.; Holden, K.R.; Dobyns, W.B.; et al. Mutations in the cilia gene ARL13B lead to the classical form of Joubert syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Khan, M.I.; Neveling, K.; Tayyab, A.; Jaffar, S.; Sadeque, A.; Ayub, H.; Abbasi, N.M.; Riaz, M.; Micheal, S.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies a novel and a recurrent BBS1 mutation in Pakistani families with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 644–653. [Google Scholar]

- Harville, H.M.; Held, S.; Diaz-Font, A.; Davis, E.E.; Diplas, B.H.; Lewis, R.A.; Borochowitz, Z.U.; Zhou, W.; Chaki, M.; Macdonald, J.; et al. Identification of 11 novel mutations in eight BBS genes by high-resolution homozygosity mapping. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.R.; Ganesh, A.; Nishimura, D.; Rattenberry, E.; Ahmed, S.; Smith, U.M.; Pasha, S.; Raeburn, S.; Trembath, R.C.; Rajab, A.; et al. Autozygosity mapping of Bardet-Biedl syndrome to 12q21.2 and confirmation of FLJ23560 as BBS10. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, Z.; Iqbal, Z.; Azam, M.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; van Bokhoven, H.; Qamar, R. A novel homozygous 10 nucleotide deletion in BBS10 causes Bardet-Biedl syndrome in a Pakistani family. Gene 2013, 519, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, B.; Mir, A.; Iqbal, H.; Li, Y.; Nurnberg, G.; Becker, C.; Qamar, R.; Nurnberg, P.; Wollnik, B. A novel familial BBS12 mutation associated with a mild phenotype: Implications for clinical and molecular diagnostic strategies. Mol. Syndromol. 2010, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, J.M.; Peters, L.M.; Riazuddin, S.; Bernstein, S.L.; Ahmed, Z.M.; Ness, S.L.; Polomeno, R.; Ramesh, A.; Schloss, M.; Srisailpathy, C.R.; et al. Usher syndrome 1D and nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness DFNB12 are caused by allelic mutations of the novel cadherin-like gene CDH23. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, E.A.; Ramaswami, G.; Janssen, S.; Chaki, M.; Allen, S.J.; Zhou, W.; Airik, R.; Hurd, T.W.; Ghosh, A.K.; Wolf, M.T.; et al. Mutation analysis of 18 nephronophthisis associated ciliopathy disease genes using a DNA pooling and next generation sequencing strategy. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 48, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.A.; Otto, E.A.; O’Toole, J.F.; Nurnberg, G.; Kennedy, M.A.; Becker, C.; Hennies, H.C.; Helou, J.; Attanasio, M.; Fausett, B.V.; et al. The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, E.A.; Helou, J.; Allen, S.J.; O’Toole, J.F.; Wise, E.L.; Ashraf, S.; Attanasio, M.; Zhou, W.; Wolf, M.T.F.; Hildebrandt, F. Mutation analysis in nephronophthisis using a combined approach of homozygosity mapping, CEL I endonuclease cleavage, and direct sequencing. Hum. Mutat. 2008, 29, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.M.; Riazuddin, S.; Ahmad, J.; Bernstein, S.L.; Guo, Y.; Sabar, M.F.; Sieving, P.; Griffith, A.J.; Friedman, T.B.; Belyantseva, I.A.; et al. PCDH15 is expressed in the neurosensory epithelium of the eye and ear and mutant alleles are responsible for both USH1F and DFNB23. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 3215–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Miller, J.J.; Corbit, K.C.; Giles, R.H.; Brauer, M.J.; Otto, E.A.; Baye, L.M.; Wen, X.; Scales, S.J.; Kwong, M.; et al. Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell 2011, 145, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, U.M.; Consugar, M.; Tee, L.J.; McKee, B.M.; Maina, E.N.; Whelan, S.; Morgan, N.V.; Goranson, E.; Gissen, P.; Lilliquist, S.; et al. The transmembrane protein meckelin (MKS3) is mutated in Meckel-Gruber syndrome and the wpk rat. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, S.J.; Badano, J.L.; Blacque, O.E.; Hill, J.; Hoskins, B.E.; Leitch, C.C.; Kim, J.C.; Ross, A.J.; Eichers, E.R.; Teslovich, T.M.; et al. Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature 2003, 425, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, R.; Fatima, A.; Naz, S. A frameshift mutation in SANS results in atypical Usher syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Safieh, L.; Alrashed, M.; Anazi, S.; Alkuraya, H.; Khan, A.O.; Al-Owain, M.; Al-Zahrani, J.; Al-Abdi, L.; Hashem, M.; Al-Tarimi, S.; et al. Autozygome-guided exome sequencing in retinal dystrophy patients reveals pathogenetic mutations and novel candidate disease genes. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartong, D.T.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveling, K.; Collin, R.W.J.; Gilissen, C.; van Huet, R.A.; Visser, L.; Kwint, M.P.; Gijsen, S.J.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Wieskamp, N.; de Ligt, J.; et al. Next-generation genetic testing for retinitis pigmentosa. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedahmadi, B.J.; Rivolta, C.; Keene, J.A.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Comprehensive screening of the USH2A gene in usher syndrome type II and non-syndromic recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Exp. Eye Res. 2004, 79, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, R.; Ayub, Q.; Mohyuddin, A.; Helgason, A.; Mazhar, K.; Mansoor, A.; Zerjal, T.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Mehdi, S.Q. Y-chromosomal DNA variation in pakistan. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 70, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, R.W.J.; van den Born, L.I.; Klevering, B.J.; de Castro-Miro, M.; Littink, K.W.; Arimadyo, K.; Azam, M.; Yazar, V.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Paun, C.C.; et al. High-resolution homozygosity mapping is a powerful tool to detect novel mutations causative of autosomal recessive RP in the dutch population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 2227–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohocki, M.M.; Perrault, I.; Leroy, B.P.; Payne, A.M.; Dharmaraj, S.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Kaplan, J.; Maumenee, I.H.; Koenekoop, R.; Meire, F.M.; et al. Prevalence of AIPL1 mutations in inherited retinal degenerative disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000, 70, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzer, S.; Leroy, B.P.; de Baere, E.; de Ravel, T.J.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Voesenek, K.; Kellner, U.; Martinez Ciriano, J.P.; de Faber, J.T.H.N.; Rohrschneider, K.; et al. Microarray-based mutation detection and phenotypic characterization of patients with leber congenital amaurosis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Stoetzel, C.; Vincent, M.C.; Leitch, C.C.; Laurier, V.; Danse, J.M.; Helle, S.; Marion, V.; Bennouna-Greene, V.; Vicaire, S.; et al. Identification of 28 novel mutations in the Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes: The burden of private mutations in an extensively heterogeneous disease. Hum. Genet. 2010, 127, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurg, A.; Tonisson, N.; Georgiou, I.; Shumaker, J.; Tollett, J.; Metspalu, A. Arrayed primer extension: Solid-phase four-color DNA resequencing and mutation detection technology. Genet. Test. 2000, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakson, K.; Zernant, J.; Kulm, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Tonisson, N.; Hawlina, M.; Ravnic-Glavac, M.; Meltzer, M.; Caruso, R.; Testa, F.; et al. Genotyping microarray (gene chip) for the ABCR (ABCA4) gene. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 22, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Fernandez, A.; Cantalapiedra, D.; Aller, E.; Vallespin, E.; guirre-Lamban, J.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Corton, M.; Riveiro-Alvarez, R.; Allikmets, R.; Trujillo-Tiebas, M.J.; et al. Mutation analysis of 272 spanish families affected by autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa using a genotyping microarray. Mol. Vis. 2010, 16, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.I.; Azam, M.; Ajmal, M.; Collin, R.W.J.; Den Hollander, A.I.; Cremers, F.P.M.; Qamar, R. The Molecular Basis of Retinal Dystrophies in Pakistan. Genes 2014, 5, 176-195. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes5010176

Khan MI, Azam M, Ajmal M, Collin RWJ, Den Hollander AI, Cremers FPM, Qamar R. The Molecular Basis of Retinal Dystrophies in Pakistan. Genes. 2014; 5(1):176-195. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes5010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Imran, Maleeha Azam, Muhammad Ajmal, Rob W. J. Collin, Anneke I. Den Hollander, Frans P. M. Cremers, and Raheel Qamar. 2014. "The Molecular Basis of Retinal Dystrophies in Pakistan" Genes 5, no. 1: 176-195. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes5010176

APA StyleKhan, M. I., Azam, M., Ajmal, M., Collin, R. W. J., Den Hollander, A. I., Cremers, F. P. M., & Qamar, R. (2014). The Molecular Basis of Retinal Dystrophies in Pakistan. Genes, 5(1), 176-195. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes5010176