Recent Advances in the Application of Piezoelectric Materials in Microrobotic Systems

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Movement Mechanism

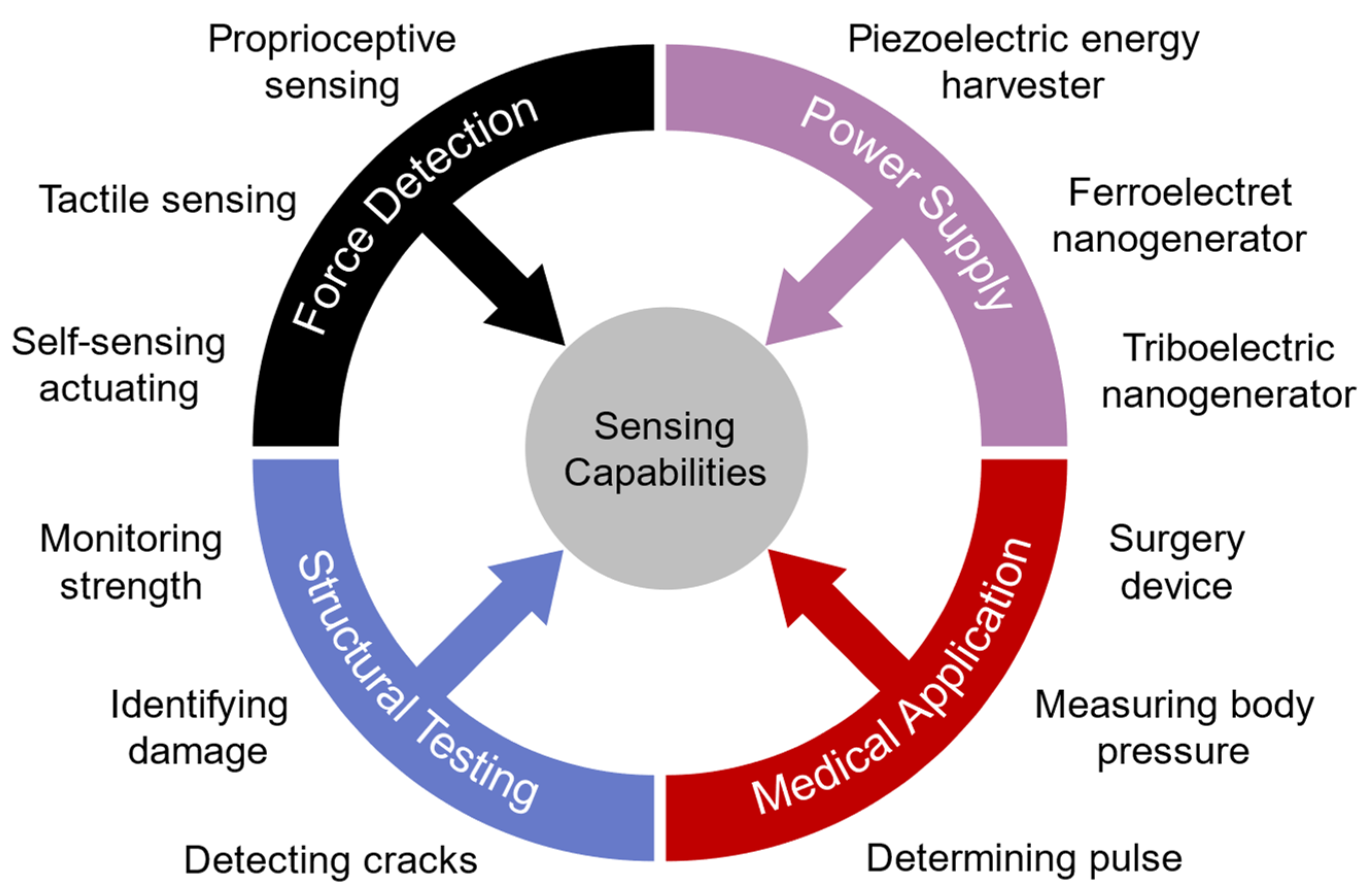

2.1. Ambulatory Locomotion

2.2. Friction-Based Locomotion

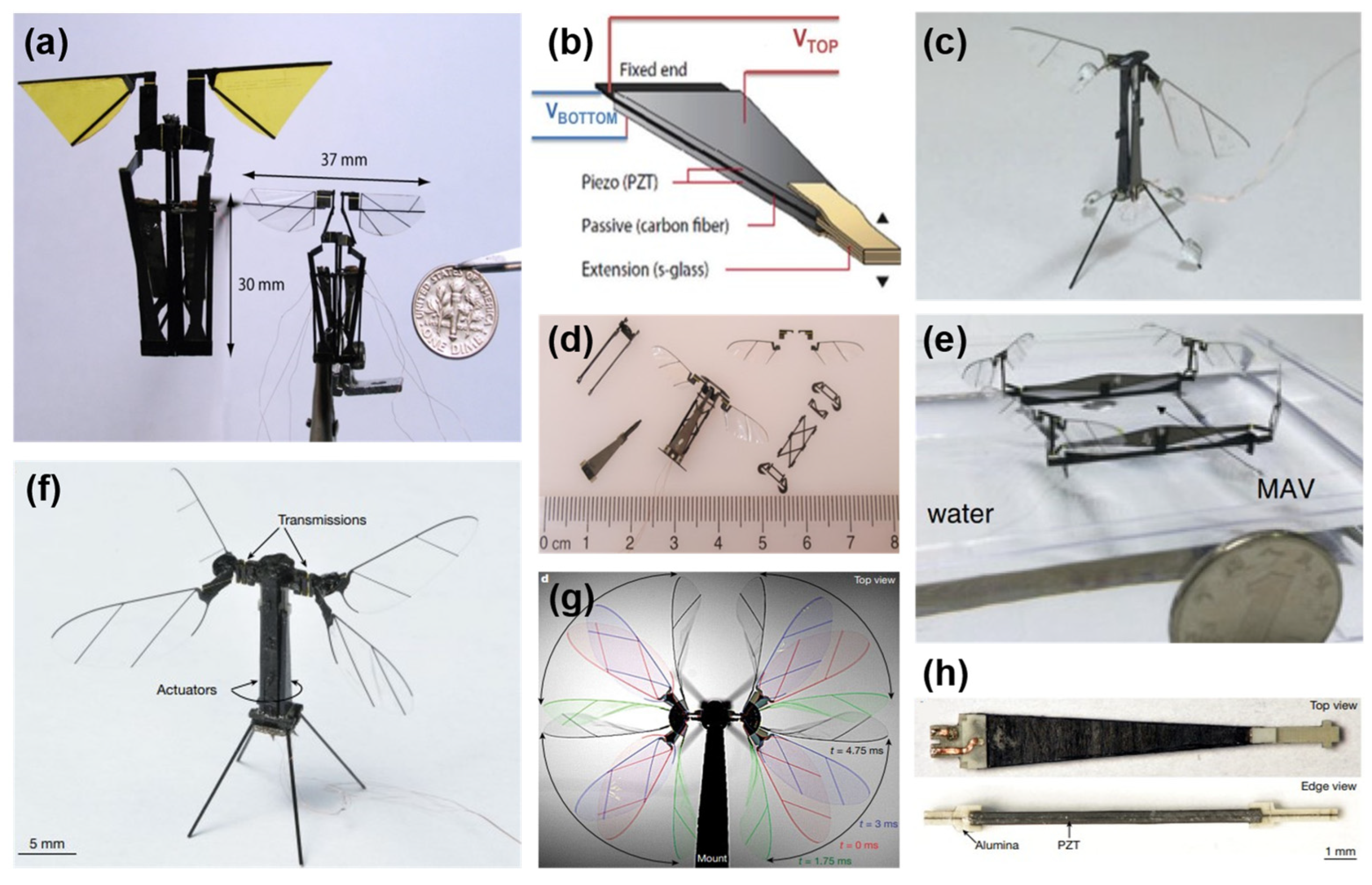

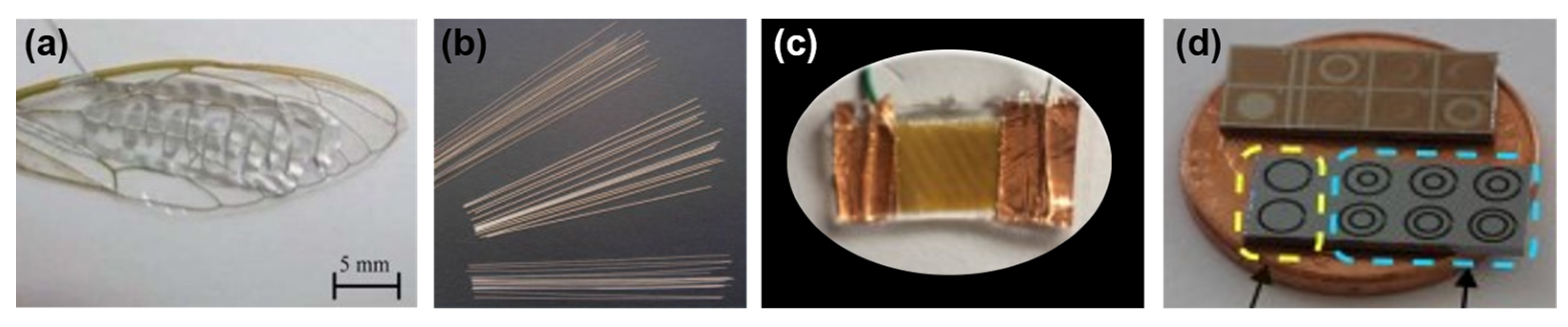

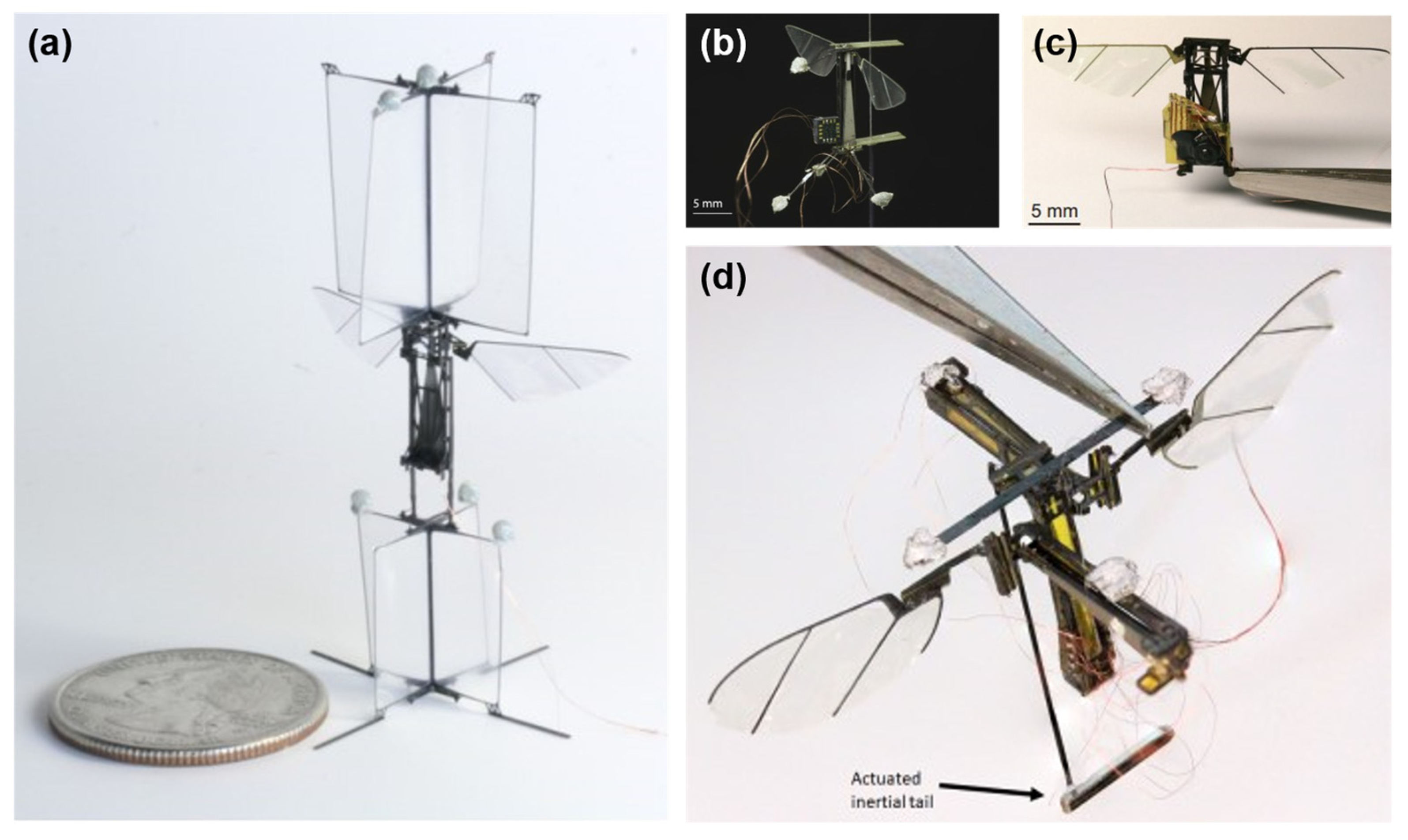

2.3. Flapping-Wing Locomotion

2.4. Amphibious and Swimming Locomotion

3. Power Supply

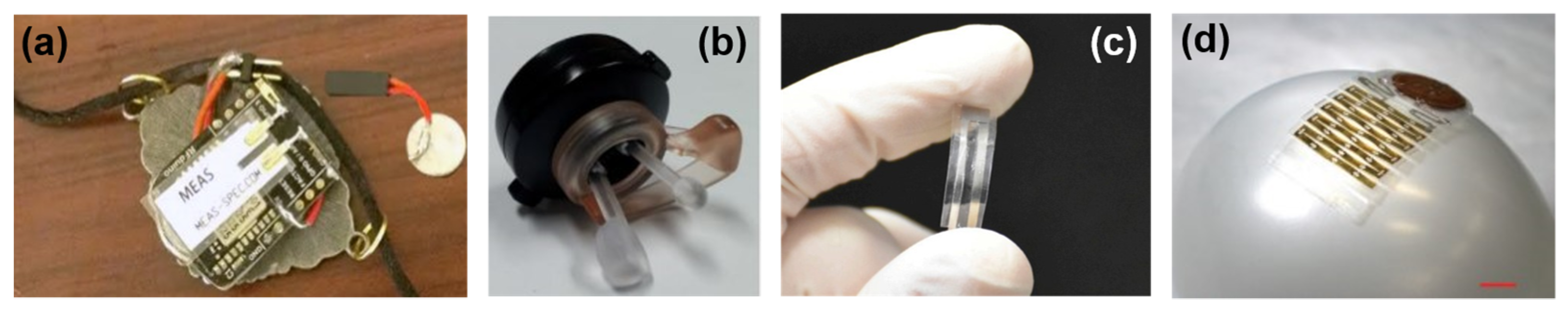

4. Sensing Capabilities

5. Control and Stability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farrell Helbling, E.; Wood, R.J. A review of propulsion, power, and control architectures for insect-scale flapping-wing vehicles. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2018, 70, 010801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapan, Y.; Yasa, O.; Yigit, B.; Yasa, I.C.; Erkoc, P.; Sitti, M. Microrobotics and microorganisms: Biohybrid autonomous cellular robots. Annu. Rev. Control Rob. Auton. Syst. 2019, 2, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.I.; Martella, D.; Nocentini, S.; Parmeggiani, C.; Taboryski, R.; Wiersma, D.S. Light—Powered Microrobots: Challenges and Opportunities for Hard and Soft Responsive Microswimmers. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Jeong, J.; Song, H.; Chung, S.K. Targeted drug delivery technology using untethered microrobots: A review. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2019, 29, 053002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, X. Compensation of hysteresis in piezoelectric actuators without dynamics modeling. Sens. Actuators A 2013, 199, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, X.; Li, Z. Inverse compensation for hysteresis in piezoelectric actuator using an asymmetric rate-dependent model. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, S.R.; Sodano, H.A. A review of power harvesting using piezoelectric materials (2003–2006). Smart Mater. Struct. 2007, 16, R1–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, M.; Sodano, H.A.; Anton, S.R. A review of energy harvesting using piezoelectric materials: State-of-the-art a decade later (2008–2018). Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.D.; Mohapatra, P.C.; Aria, A.I.; Christie, G.; Mishra, Y.K.; Hofmann, S.; Thakur, V.K. Piezoelectric Materials for Energy Harvesting and Sensing Applications: Roadmap for Future Smart Materials. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K. Piezoelectric actuators 2006. J. Electroceram. 2008, 20, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov, S.N.; Soloviev, A.N.; Parinov, I.A.; Cherpakov, A.V.; Chebanenko, V.A. Piezoelectric Actuators and Generators for Energy Harvesting: Research and Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Arockiarajan, A.; Menzel, A.; Delibas, B.; Seemann, W. Computational modeling of rate-dependent domain switching in piezoelectric materials. Eur. J. Mech. -A/Solids 2006, 25, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, R.; Avadhanula, S.; Groff, R.; Steltz, E.; Wood, R.; Fearing, R.S. Towards a 3g crawling robot through the integration of microrobot technologies. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 May 2006; pp. 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K.L.; Wood, R.J. Robustness of centipede-inspired millirobot locomotion to leg failures. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1472–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Itatsu, Y.; Torii, A.; Ueda, A. Inchworm type microrobot using friction force control mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Symposium on Micro-NanoMechatronics and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 6–9 November 2011; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, C.B.; Gomez, H.C.; Acker-James, D.; Teal, D.; Li, W.; Pister, K.S. 15 millinewton force, 1 millimeter displacement, low-power MEMS gripper. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 January 2020; pp. 485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.Y.; Chirarattananon, P.; Fuller, S.B.; Wood, R.J. Controlled flight of a biologically inspired, insect-scale robot. Science 2013, 340, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, F.; Zimmermann, K.; Volkova, T.; Minchenya, V.T. An amphibious vibration-driven microrobot with a piezoelectric actuator. Regul. Chaotic Dyn. 2013, 18, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpelson, M.; Wei, G.-Y.; Wood, R.J. A review of actuation and power electronics options for flapping-wing robotic insects. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008; pp. 779–786. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J. A review of piezoelectric energy harvesting based on vibration. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 12, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, İ.M.; Akça, E. Design of a piezoelectric based tactile sensor with bio-inspired micro/nano-pillars. Tribol. Int. 2013, 59, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ihn, J.-B.; Chang, F.-K. Detection and monitoring of hidden fatigue crack growth using a built-in piezoelectric sensor/actuator network: I. Diagnostics. Smart Mater. Struct. 2004, 13, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Carreira, S.C.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, C.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; Farrow, I.; Scarpa, F.; Rossiter, J. Stretchable piezoelectric sensing systems for self-powered and wireless health monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1900100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, Z.E.; Fuller, S.B.; Chirarattananon, P.; Prez-Arancibia, N.; Greenberg, J.D.; Wood, R.J. A hovering flapping-wing microrobot with altitude control and passive upright stability. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 3209–3216. [Google Scholar]

- Chirarattananon, P.; Chen, Y.; Helbling, E.F.; Ma, K.Y.; Cheng, R.; Wood, R.J. Dynamics and flight control of a flapping-wing robotic insect in the presence of wind gusts. Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20160080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Arancibia, N.O.; Whitney, J.P.; Wood, R.J. Lift force control of flapping-wing microrobots using adaptive feedforward schemes. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2011, 18, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirarattananon, P.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Adaptive control of a millimeter-scale flapping-wing robot. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2014, 9, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Arancibia, N.O.; Duhamel, P.-E.J.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Model-free control of a hovering flapping-wing microrobot. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2015, 77, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, T.S.; Ferrari, S.; Fuller, S.B.; Wood, R.J. Spiking neural network (SNN) control of a flapping insect-scale robot. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 3381–3388. [Google Scholar]

- Chirarattananon, P.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Single-loop control and trajectory following of a flapping-wing microrobot. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–5 June 2014; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Quan, Q.; Deng, J.; Yu, H. A quadruped micro-robot based on piezoelectric driving. Sensors 2018, 18, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; He, G.; Di, J.; Zhao, L.; Su, T.; Zhang, M.; Hou, Z. Fast-moving piezoelectric micro-robotic fish with double caudal fins. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2021, 140, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabagi, V.; Hines, L.; Sitti, M. Design and manufacturing of a controllable miniature flapping wing robotic platform. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2012, 31, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, M.; Helbling, E.F.; Zhang, X.; Wood, R.; Brooks, D.; Wei, G.-Y. A low mass power electronics unit to drive piezoelectric actuators for flying microrobots. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 3180–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baisch, A.T.; Sreetharan, P.S.; Wood, R.J. Biologically-inspired locomotion of a 2g hexapod robot. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 5360–5365. [Google Scholar]

- Baisch, A.T.; Heimlich, C.; Karpelson, M.; Wood, R.J. HAMR3: An autonomous 1.7 g ambulatory robot. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; pp. 5073–5079. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K.L.; Wood, R.J. Myriapod-like ambulation of a segmented microrobot. Auton. Robot. 2011, 31, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.L.; Wood, R.J. Towards a multi-segment ambulatory microrobot. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 1196–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Baisch, A.T.; Ozcan, O.; Goldberg, B.; Ithier, D.; Wood, R.J. High speed locomotion for a quadrupedal microrobot. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2014, 33, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, S.A.; Fleming, A.J.; Yong, Y.K. Miniature Resonant Ambulatory Robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando-García, J.; García-Caraballo, J.L.; Ruiz-Díez, V.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.L. Comparative Study of Traveling and Standing Wave-Based Locomotion of Legged Bidirectional Miniature Piezoelectric Robots. Micromachines 2021, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Shin, M.; Rudy, R.Q.; Kao, C.; Pulskamp, J.S.; Polcawich, R.G.; Oldham, K.R. Thin-film piezoelectric and high-aspect ratio polymer leg mechanisms for millimeter-scale robotics. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2017, 1, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigoli, A.K.; Vossoughi, G. Dynamic Modeling of Stick-Slip Motion in a Legged, Piezoelectric Driven Microrobot. Int. J. Adv. Rob. Syst. 2010, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saadabad, N.A.; Moradi, H.; Vossoughi, G. Dynamic modeling, optimized design, and fabrication of a 2DOF piezo-actuated stick-slip mobile microrobot. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 133, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, H.; Salarieh, H.; Vossoughi, G. Study of a piezo-electric actuated vibratory micro-robot in stick-slip mode and investigating the design parameters. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 89, 1927–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutama, R.Y.; Khalil, M.M.; Mashimo, T. A Millimeter-Scale Rolling Microrobot Driven by a Micro-Geared Ultrasonic Motor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 8158–8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.H.; Tzou, S.S.; Shiu, R.Y. A novel wireless and mobile piezoelectric micro robot. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Xi’an, China, 4–7 August 2010; pp. 1158–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, I.A.; Hwang, G.; Agnus, J.; Rakotondrabe, M.; Chaillet, N.; Régnier, S. First experiments on magpier: A planar wireless magnetic and piezoelectric microrobot. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, J.C.; Escareno, J.A.; Etcheverry, G.; Rakotondrabe, M. Getting started with peas-based flapping-wing mechanisms for micro aerial systems. Actuators 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpelson, M.; Wei, G.-Y.; Wood, R.J. Driving high voltage piezoelectric actuators in microrobotic applications. Sens. Actuators A 2012, 176, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ke, X.; Lou, X.; Zhou, S. The design and microfabrication of a sub 100 mg insect-scale flapping-wing robot. Micro Nano Lett. 2017, 12, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafferis, N.T.; Helbling, E.F.; Karpelson, M.; Wood, R.J. Untethered flight of an insect-sized flapping-wing microscale aerial vehicle. Nature 2019, 570, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Zou, Y.; Ou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Piezoelectric-driven self-assembling micro air vehicle with bionic reciprocating wings. Electron. Lett. 2018, 54, 551–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukewad, Y.M.; James, J.; Singh, A.; Fuller, S. RoboFly: An Insect-Sized Robot With Simplified Fabrication That Is Capable of Flight, Ground, and Water Surface Locomotion. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 2025–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Z.; Liu, J.-H.; Dong, M.; Müller, L.; Chatzipirpiridis, G.; Hu, C.; Terzopoulou, A.; Torlakcik, H.; Wang, X.; Mushtaq, F. Magnetically driven piezoelectric soft microswimmers for neuron-like cell delivery and neuronal differentiation. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 1512–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sui, F.; Huang, Y.; Guo, R.; Lin, L. Micro Swimming Robots Powered by a Single-Axis Alternating Magnetic Field with Controllable Manipulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 21st International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (Transducers), Orlando, FL, USA, 20–24 June 2021; pp. 357–360. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.-T.; Yen, C.-K.; Lin, L.; Lu, Y.-S.; Li, H.-W.; Huang, J.C.-C.; Kuo, S.-W. Energy harvesting with piezoelectric poly(γ-benzyl-l-glutamate) fibers prepared through cylindrical near-field electrospinning. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 21563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Dommer, M.; Chang, C.; Lin, L. Piezoelectric nanofibers for energy scavenging applications. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Zhang, L.; Gui, J.; Cui, H.; Guo, S. A flexible piezoelectric nanogenerator based on aligned P (VDF-TrFE) nanofibers. Micromachines 2019, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yun, K.-S. Helical piezoelectric energy harvester and its application to energy harvesting garments. Micromachines 2017, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beker, L.; Benet, A.; Meybodi, A.T.; Eovino, B.; Pisano, A.P.; Lin, L. Energy harvesting from cerebrospinal fluid pressure fluctuations for self-powered neural implants. Biomed. Microdevices 2017, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qichang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wei, W. Theoretical Study on Widening Bandwidth of Piezoelectric Vibration Energy Harvester with Nonlinear Characteristics. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Torres, D.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Sepúlveda, N. Flexible and biocompatible polypropylene ferroelectret nanogenerator (FENG): On the path toward wearable devices powered by human motion. Nano Energy 2016, 30, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Ferroelectret Nanogenerator (FENG) for Mechanical Energy Harvesting and Self-Powered Flexible Electronics. Ph.D. Thesis, Michigan State University, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Torres, D.; Díaz, R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Lin Wang, Z.; Sepúlveda, N. Nanogenerator-based dual-functional and self-powered thin patch loudspeaker or microphone for flexible electronics. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Figueroa, J.; Pastrana, J.J.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Sepúlveda, N. Flexible Ferroelectret Polymer for Self-Powering Devices and Energy Storage Systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 17400–17409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Figueroa, J.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Sepúlveda, N. Understanding the dynamic response in ferroelectret nanogenerators to enable self-powered tactile systems and human-controlled micro-robots. Nano Energy 2019, 63, 103852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.; Iyer, V.; Chukewad, Y.; Gollakota, S.; Fuller, S.B. Liftoff of a 190 mg laser-powered aerial vehicle: The lightest wireless robot to fly. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 3587–3594. [Google Scholar]

- Karpelson, M.; Waters, B.H.; Goldberg, B.; Mahoney, B.; Ozcan, O.; Baisch, A.; Meyitang, P.-M.; Smith, J.R.; Wood, R.J. A wirelessly powered, biologically inspired ambulatory microrobot. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–5 June 2014; pp. 2384–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, V.; Gaensbauer, H.; Daniel, T.L.; Gollakota, S. Wind dispersal of battery-free wireless devices. Nature 2022, 603, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. External Power-Driven Microrobotic Swarm: From Fundamental Understanding to Imaging-Guided Delivery. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, O.; Erkoc, P.; Alapan, Y.; Sitti, M. Microalga-powered microswimmers toward active cargo delivery. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1804130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlbusch, S.; Fatikow, S. Force sensing in microrobotic systems-an overview. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems. Surfing the Waves of Science and Technology (Cat. No. 98EX196), Lisboa, Portugal, 7–10 September 1998; pp. 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Choi, W.; Yoo, Y.K.; Hwang, K.S.; Lee, S.-M.; Kang, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.H. A micro-fabricated force sensor using an all thin film piezoelectric active sensor. Sensors 2014, 14, 22199–22207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, G.; Chowdhury, S.; Guix, M.; Johnson, B.V.; Bi, C.; Cappelleri, D. Towards functional mobile microrobotic systems. Robotics 2019, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, K.; Jafferis, N.T.; Doshi, N.; Goldberg, B.; Wood, R.J. Concomitant sensing and actuation for piezoelectric microrobots. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 065028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, N.; Jayaram, K.; Castellanos, S.; Kuindersma, S.; Wood, R.J. Effective locomotion at multiple stride frequencies using proprioceptive feedback on a legged microrobot. Bioinspiration Biomim. 2019, 14, 056001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Gravish, N. Piezoelectric actuators with on-board sensing for micro-robotic applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 115036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, V.; Najafi, A.; James, J.; Fuller, S.; Gollakota, S. Wireless steerable vision for live insects and insect-scale robots. Sci. Rob. 2020, 5, eabb0839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Jiao, P.; Zhu, Z. Combination of piezoelectric and triboelectric devices for robotic self-powered sensors. Micromachines 2021, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, K.; Chansomphou, L.; Murakami, H.; Okuyama, M. Ultrasonic micro array sensors using piezoelectric thin films and resonant frequency tuning. Sens. Actuators A 2004, 114, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, W. A monolithic self-sensing precision stage: Design, modeling, calibration, and hysteresis compensation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2014, 20, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.; Liao, W. Sensitivity analysis and energy harvesting for a self-powered piezoelectric sensor. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2005, 16, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Cai, J.; Wang, M.; Lv, X. A piezoelectric bimorph micro-gripper with micro-force sensing. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Information Acquisition, Hong Kong, China, 27 June 2005–3 July 2005; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Tan, C.Y.; Yao, K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.F. A miniaturized wireless accelerometer with micromachined piezoelectric sensing element. Sens. Actuators A 2016, 241, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Yousefi, A.A. Piezoelectric sensor based on electrospun PVDF-MWCNT-Cloisite 30B hybrid nanocomposites. Org. Electron. 2017, 50, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yan, X.; Gong, L.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y. Improved piezoelectric sensing performance of P (VDF–TrFE) nanofibers by utilizing BTO nanoparticles and penetrated electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 7379–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, W.; Sepulveda, N. Performance of Self-Powered, Water-Resistant Bending Sensor Using Transverse Piezoelectric Effect of Polypropylene Ferroelectret Polymer. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 10327–10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Cheng, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, M. Identifying technology for structural damage based on the impedance analysis of piezoelectric sensor. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2522–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.W.; Qureshi, A.R.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yun, C.B. Piezoelectric sensor based nondestructive active monitoring of strength gain in concrete. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 055002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Song, G.; Ren, Z. Piezo-based wireless sensor network for early-age concrete strength monitoring. Optik 2016, 127, 2983–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.-H.; Tsai, M.-Y. Acoustic emission sensor with structure-enhanced sensing mechanism based on micro-embossed piezoelectric polymer. Sens. Actuators A 2010, 162, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Egbe, K.-J.I.; Xie, Y.; Matin Nazar, A.; Alavi, A.H. Piezoelectric sensing techniques in structural health monitoring: A state-of-the-art review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalange, A.; Gangal, S. Piezoelectric sensor for human pulse detection. Def. Sci. J. 2007, 57, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantarian, H.; Alshurafa, N.; Le, T.; Sarrafzadeh, M. Monitoring eating habits using a piezoelectric sensor-based necklace. Comput. Biol. Med. 2015, 58, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H.; Jang, D.-G.; Park, J.W.; Youm, S.-K. Wearable sensing of in-ear pressure for heart rate monitoring with a piezoelectric sensor. Sensors 2015, 15, 23402–23417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yao, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhu, Z. A piezoelectric sensing neuron and resonance synchronization between auditory neurons under stimulus. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, E.J.; Ke, K.; Chorsi, M.T.; Wrobel, K.S.; Miller, A.N.; Patel, A.; Kim, I.; Feng, J.; Yue, L.; Wu, Q. Biodegradable piezoelectric force sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadnia, M.; Kottapalli, A.G.P.; Shen, Z.; Miao, J.; Triantafyllou, M. Flexible and surface-mountable piezoelectric sensor arrays for underwater sensing in marine vehicles. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 3918–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Deng, W.; Gao, Y.; Xiong, D.; Yan, C.; He, X.; Yang, T.; Jin, L.; Chu, X.; Zhang, H. Rich lamellar crystal baklava-structured PZT/PVDF piezoelectric sensor toward individual table tennis training. Nano Energy 2019, 59, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, Z.E.; Wood, R.J. A flapping-wing microrobot with a differential angle-of-attack mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6–10 May 2013; pp. 1381–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Helbling, E.F.; Fuller, S.B.; Wood, R.J. Pitch and yaw control of a robotic insect using an onboard magnetometer. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–5 June 2014; pp. 5516–5522. [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel, P.-E.J.; Pérez-Arancibia, N.O.; Barrows, G.L.; Wood, R.J. Altitude feedback control of a flapping-wing microrobot using an on-board biologically inspired optical flow sensor. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; pp. 4228–4235. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, S.B.; Karpelson, M.; Censi, A.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Controlling free flight of a robotic fly using an onboard vision sensor inspired by insect ocelli. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teoh, Z.E.; Wood, R.J. A bioinspired approach to torque control in an insect-sized flapping-wing robot. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, São Paulo, Brazil, 12–15 August 2014; pp. 911–917. [Google Scholar]

- Chukewad, Y.; Fuller, S. Yaw Control of a Hovering Flapping-Wing Aerial Vehicle With a Passive Wing Hinge. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fuller, S.B.; Dantu, K. Quadrobee: Simulating flapping wing aerial vehicle dynamics on a quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 5957–5964. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Libby, T.; Fuller, S.B. Rapid inertial reorientation of an aerial insect-sized robot using a piezo-actuated tail. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 4154–4160. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Planar Aerial Reorientation of an Insect Scale Robot Using Piezo-Actuated Tail Like Appendage; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Mao, J.; Chirarattananon, P.; Helbling, E.F.; Hyun, N.-S.P.; Clarke, D.R.; Wood, R.J. Controlled flight of a microrobot powered by soft artificial muscles. Nature 2019, 575, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, J.; Fuller, S. A high-voltage power electronics unit for flying insect robots that can modulate wing thrust. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May 2021–5 June 2021; pp. 7212–7218. [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan, O.; Baisch, A.T.; Wood, R.J. Design and feedback control of a biologically-inspired miniature quadruped. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1438–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi, N.; Jayaram, K.; Goldberg, B.; Wood, R.J. Phase control for a legged microrobot operating at resonance. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May 2017–3 June 2017; pp. 5969–5975. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, B.; Zufferey, R.; Doshi, N.; Helbling, E.F.; Whittredge, G.; Kovac, M.; Wood, R.J. Power and control autonomy for high-speed locomotion with an insect-scale legged robot. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.; Tavakolpour-Saleh, A.R.; Norouzi, A. Optimal nonlinear PID control of a micro-robot equipped with vibratory actuator using ant colony algorithm: Simulation and experiment. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2020, 99, 773–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, L.; Fruchard, M.; Ferreira, A. Adaptive controller and observer for a magnetic microrobot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2013, 29, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmand, M.J.; Sharifi, M. Navigation and control of endovascular helical swimming microrobot using dynamic programing and adaptive sliding mode strategy. In Control Systems Design of Bio-Robotics and Bio-Mechatronics with Advanced Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Yang, Z.; Ferreira, A.; Zhang, L. Control and autonomy of microrobots: Recent progress and perspective. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, E.; Giltinan, J.; Sitti, M. Independent control of multiple magnetic microrobots in three dimensions. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, L. Motion control in magnetic microrobotics: From individual and multiple robots to swarms. Annu. Rev. Control Rob. Auton. Syst. 2021, 4, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Movement Mechanism | Author | Year | Weight | Length Scale | Speed | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory | Sahai et al. | 2006 | 3.1 g | mm | 10 mm/s | [13] |

| Ambulatory | Hoffman and Wood | 2011 | 750 mg | mm | 0.3 mm/s (0.1 bl/s) | [37] |

| Ambulatory | Baisch et al. | 2014 | 1.27 g | mm | 440 mm/s (10.1 bl/s ) | [39] |

| Ambulatory | Rios et al. | 2017 | 16 g | mm | 520 mm/s | [40] |

| Ambulatory | García et al. | 2021 | 250 mg | mm | 280 mm/s (14 bl/s) | [41] |

| Friction-based | Hutama et al. | 2021 | 640 mg | mm | 5.6 mm/s | [46] |

| Friction-based | Pan et al. | 2010 | 100 g | mm | 14 mm/s | [47] |

| Friction-based | Su et al. | 2018 | 49.8 g | mm | 33.45 mm/s | [31] |

| Flapping-wing | Ma et al. | 2013 | 80 mg | mm | - | [17] |

| Flapping-wing | Lok et al. | 2017 | 70 mg | mm | - | [34] |

| Flapping-wing | Zou et al. | 2017 | 84 mg | mm | - | [51] |

| Flapping-wing | Zhou et al. | 2018 | 247 mg | mm | - | [52] |

| Amphibious | Becker et al. | 2013 | 2.5 g | mm | 30 mm/s | [18] |

| Amphibious | Chukewad et al. | 2021 | 74 mg | mm | 5 mm/s | [54] |

| Swimming | Zhao et al. | 2021 | 1.93 g | mm | 45 mm/s | [32] |

| Swimming | Sui et al. | 2021 | - | mm | 19.1 bl/s | [56] |

| Authors | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Fahlbusch and Fatikow | Force sensor in microgripper | [73] |

| Koç and Akça | Tactile sensing | [21] |

| Lee et al. | Biomedical applications | [74] |

| Adam et al. | Real-time micro-force sensing | [75] |

| Jayaram et al. | Control and tracking trajectories | [76] |

| Doshi et al. | Leg trajectories estimation and control | [77] |

| Chopra and Gravish | Detecting wing-collision | [78] |

| Iyer et al. | Object tracking | [79] |

| Yamashita et al. | Measurement of position | [81] |

| Chen and Li | Monitoring displacement and dynamic features | [82] |

| Ng and Liao | Self-powered sensors | [83] |

| Huang et al. | Identifying micro-force | [84] |

| Shen et al. | Measuring acceleration | [85] |

| Hosseini and Yousefi | Flexible force sensor | [86] |

| Hu et al. | Dynamic loading observation | [87] |

| Cao et al. | Athletic performance | [88] |

| Ihn and Chang | Identifying fatigue cracks | [22] |

| Xu et al. | Structural damage identifying | [89] |

| Shin et al. | Structural strength monitoring | [90] |

| Chen et al. | Structural strength monitoring | [91] |

| Feng and Tsai | Industrial transducers | [92] |

| Kalange and Gangal | Human pulse measuring | [94] |

| Kalantarian et al. | Monitoring eating habits | [95] |

| Park et al. | Heart rate measurement | [96] |

| Zhou et al. | Sound signal detection | [97] |

| Curry et al. | Internal body pressure | [98] |

| Sun et al. | Continuous health monitoring | [23] |

| Asadnia et al. | Avoiding obstacles | [99] |

| Tian et al. | Training for table tennis | [100] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fath, A.; Xia, T.; Li, W. Recent Advances in the Application of Piezoelectric Materials in Microrobotic Systems. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13091422

Fath A, Xia T, Li W. Recent Advances in the Application of Piezoelectric Materials in Microrobotic Systems. Micromachines. 2022; 13(9):1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13091422

Chicago/Turabian StyleFath, Alireza, Tian Xia, and Wei Li. 2022. "Recent Advances in the Application of Piezoelectric Materials in Microrobotic Systems" Micromachines 13, no. 9: 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13091422