Identification of Distinct Bacillus thuringiensis 4A4 Nematicidal Factors Using the Model Nematodes Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

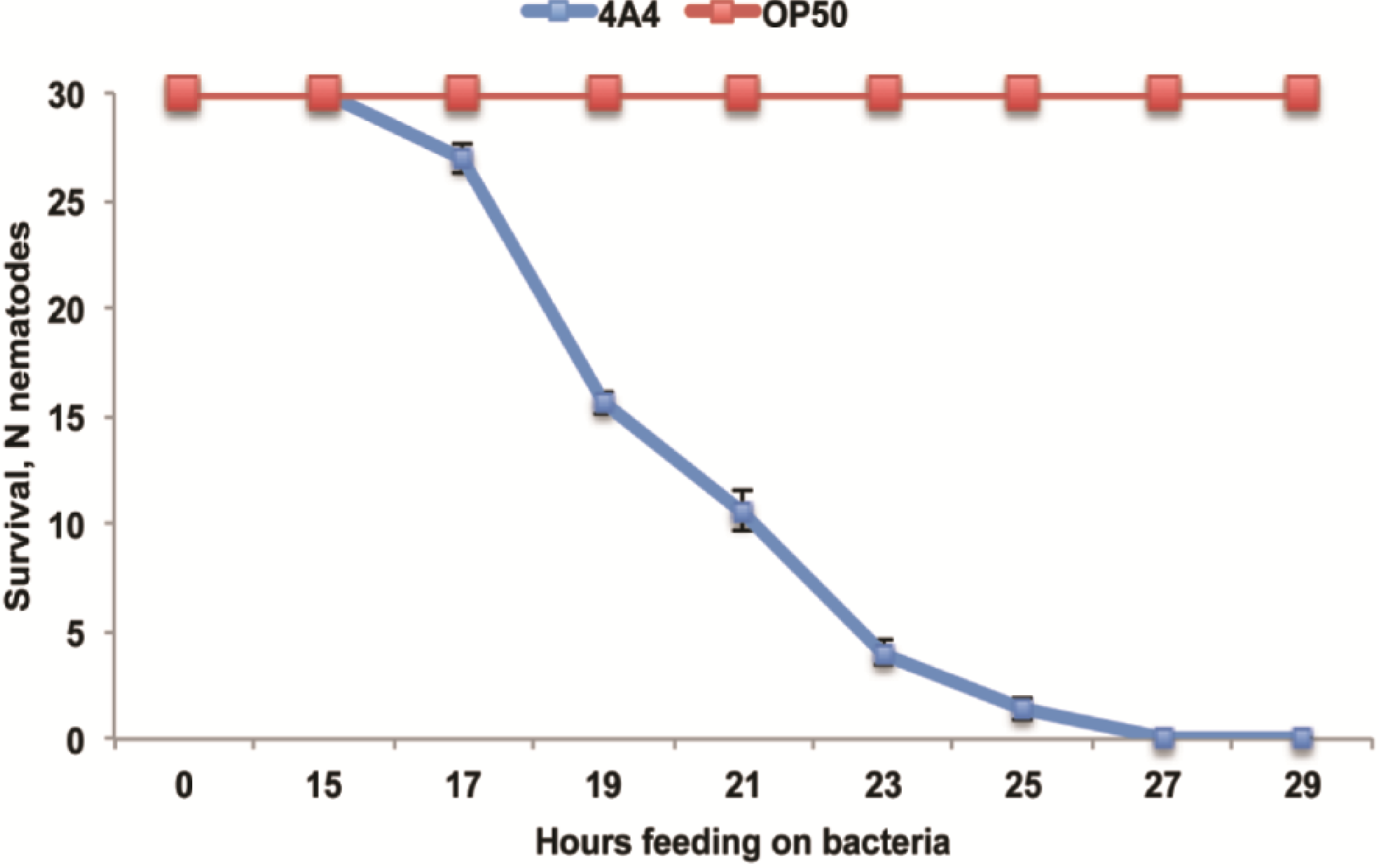

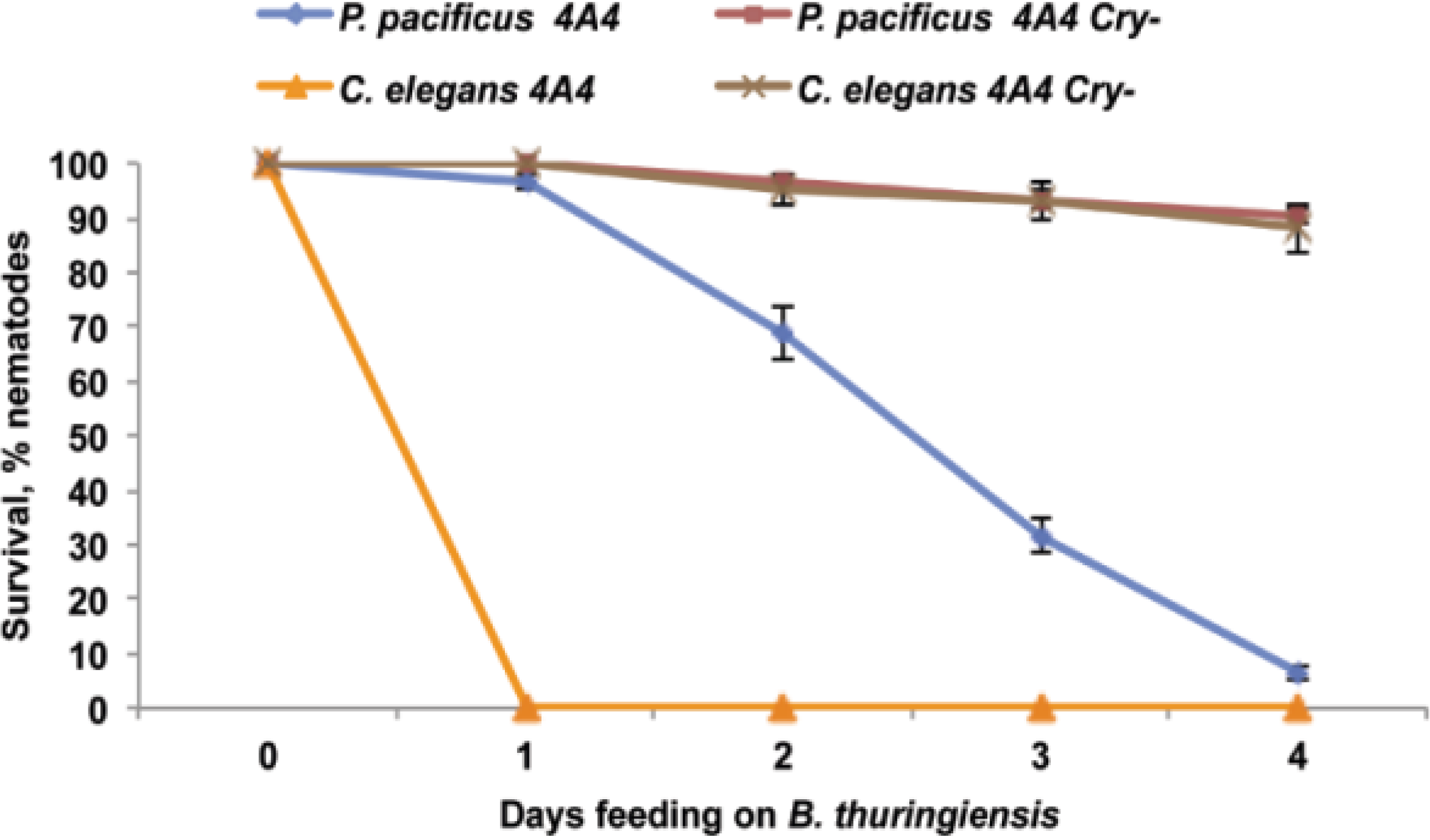

2.1. B. thuringiensis 4A4 Is Virulent to P. pacificus

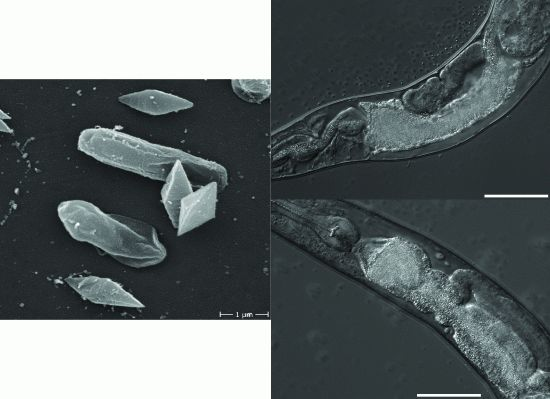

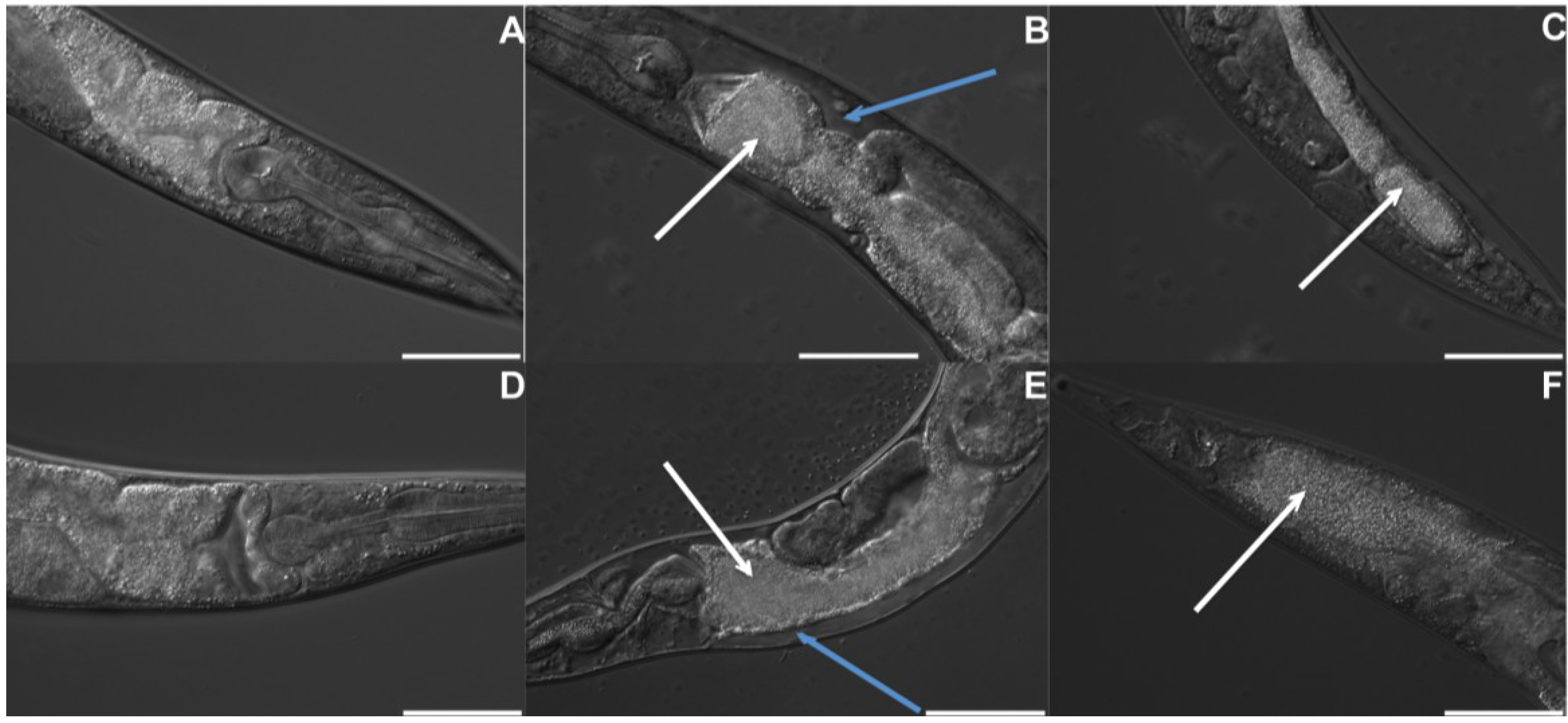

2.2. B. thuringiensis 4A4 Damages Intestines of P. pacificus and C. elegans

2.3. B. thuringiensis 4A4 Is Avoided by Nematodes

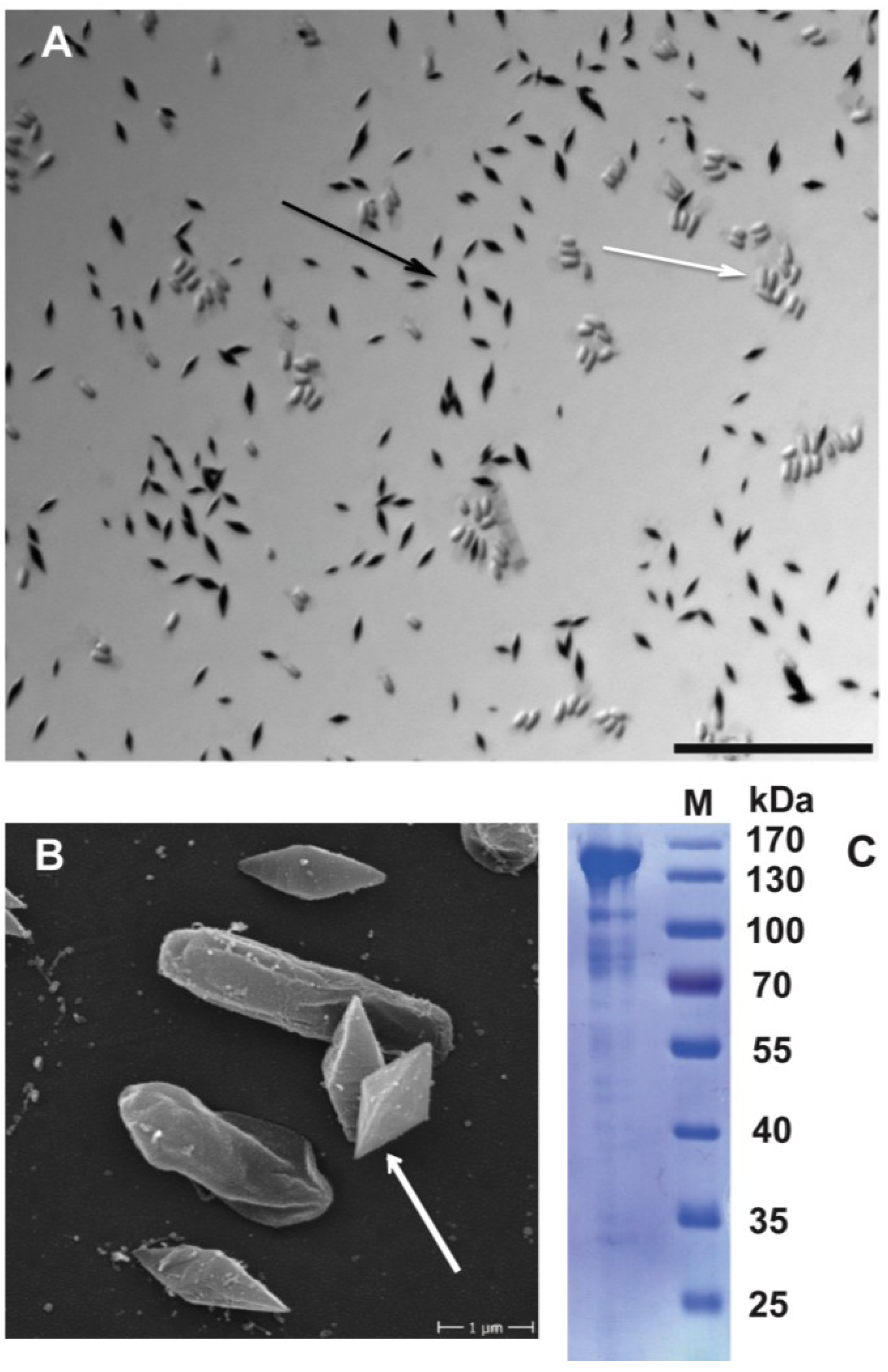

2.4. B. thuringiensis 4A4 Cry Toxins Are Involved in Nematode Killing

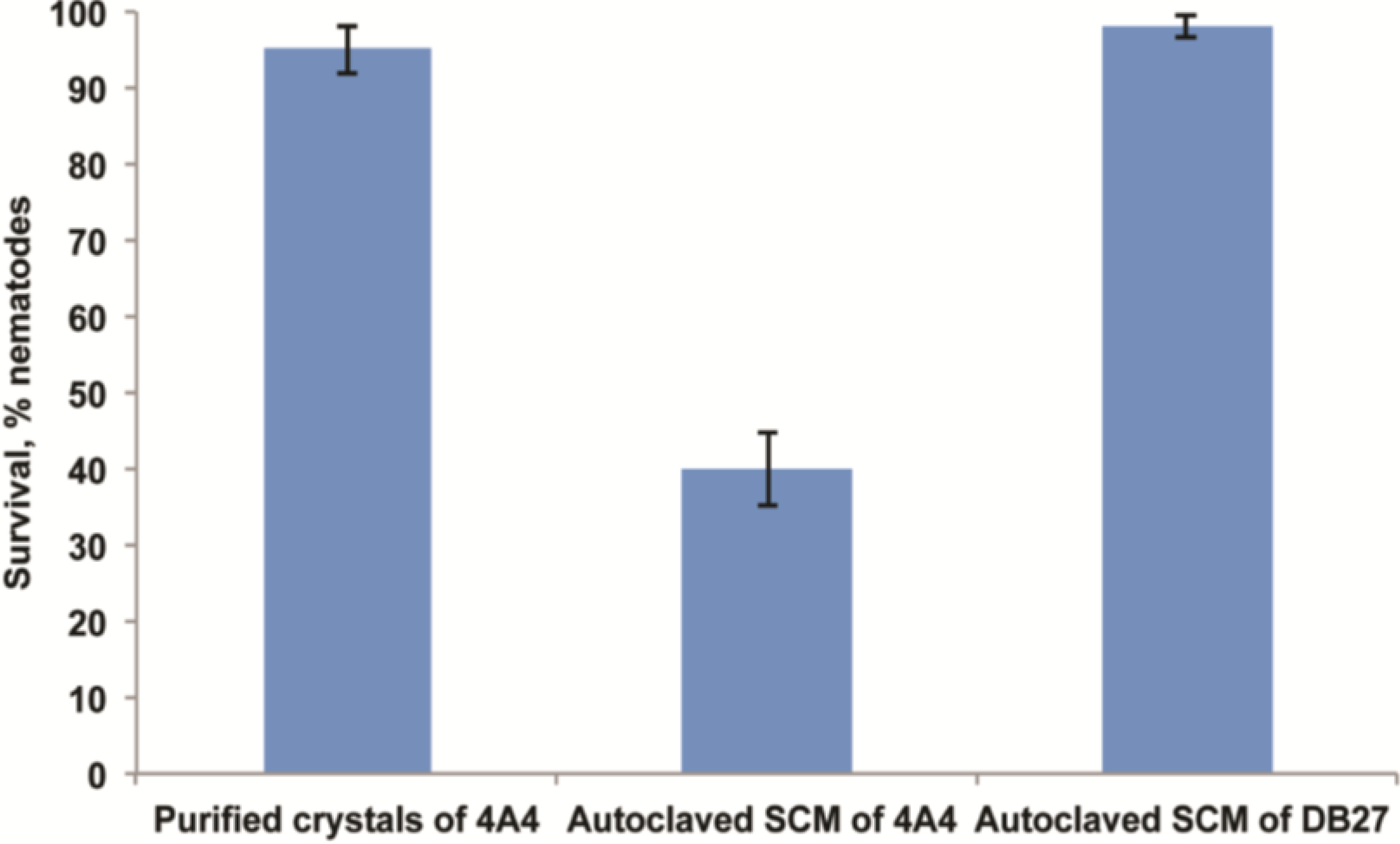

2.5. Identification of Potential Toxins

2.6. Functional Validation of Toxins

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Nematode and Bacterial Strains

3.2. Nematode Killing Assays

3.3. Chemotaxis Assay

3.4. Coomassie Stain and Electron Microscopy of Crystals

3.5. Solubilization and SDS-PAGE Profiling of Crystal Proteins

3.6. Toxin Cloning, Protein Expression and Killing Assay

3.7. Effect of Purified Crystals and SCM on Survival

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bravo, A.; Likitvivatanavong, S.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Bacillus thuringiensis: A story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Gómez, I.; Porta, H.; García-Gómez, B.I.; Rodriguez-Almazan, C.; Pardo, L.; Soberón, M. Evolution of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry toxins insecticidal activity. Microb. Biotechnol. 2013, 6, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-López, L.; Soberón, M.; Bravo, A. Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal three-domain Cry toxins: Mode of action, insect resistance and consequences for crop protection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 2007, 49, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, M.; López-Díaz, J.A.; Bravo, A. Cyt toxins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis: A protein fold conserved in several pathogenic microorganisms. Peptides 2013, 41, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, M.; Pardo, L.; Muñóz-Garay, C.; Sánchez, J.; Gómez, I.; Porta, H.; Bravo, A. Pore formation by Cry toxins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 677, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maagd, R.A.; Bravo, A.; Crickmore, N. How Bacillus thuringiensis has evolved specific toxins to colonize the insect world. Trends Genet. 2001, 17, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dov, E. Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis and its dipteran-specific toxins. Toxins 2014, 6, 1222–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, B.; Johnston, P.R.; Nielsen-LeRoux, C.; Lereclus, D.; Crickmore, N. Bacillus thuringiensis: An impotent pathogen? Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, C.S.; Boets, A.; van Rie, J.; Ferré, J. Screening and identification of vip genes in Bacillus thuringiensis strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, J.J.; Warren, G.W.; Mullins, M.A.; Nye, G.J.; Craig, J.A.; Koziel, M.G. Vip3A, a novel Bacillus thuringiensis vegetative insecticidal protein with a wide spectrum of activities against lepidopteran insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5389–5394. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, G.W. Vegetative insecticidal proteins: Novel proteins for control of corn pests. In Advances in Insect Control: The Role of Transgenic Plants; Carozzi, N., Koziel, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 1997; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Espinasse, S.; Gohar, M.; Chaufaux, J.; Buisson, C.; Perchat, S.; Sanchis, V.; Espinasse, S.; Gohar, M.; Chaufaux, J.; Buisson, C. Correspondence of high levels of β-exotoxin I and the presence of cry1B in Bacillus thuringiensis correspondence of high levels of β-Exotoxin I and the presence of cry1B in Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4182–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y.; Ruan, L.-F.; Hu, Z.-F.; Peng, D.-H.; Cao, S.-Y.; Yu, Z.-N.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.-S.; Sun, M. Genome-wide screening reveals the genetic determinants of an antibiotic insecticide in Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 39191–39200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara Hernández, C.; Martı́nez, C.; Porcar, M.; Caballero, P.; Ferré, J. Correlation between serovars of Bacillus thuringiensis and type I β-exotoxin production. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2003, 82, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.-Z.; Hale, K.; Carta, L.; Platzer, E.; Wong, C.; Fang, S.-C.; Aroian, R.V. Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins that target nematodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2760–2765. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Liu, M.; Peng, D.; Ji, S.; Wang, P.; Yu, Z.; Sun, M. New strategy for isolating novel nematicidal crystal protein genes from Bacillus thuringiensis strain YBT-1518. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 6997–7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatsenko, I.; Boichenko, I.; Sommer, R.J. Bacillus thuringiensis DB27 produces two novel protoxins, Cry21Fa1 and Cry21Ha1, which act synergistically against nematodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3266–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.-Y.; Los, F.C.O.; Huffman, D.L.; Wachi, S.; Kloft, N.; Husmann, M.; Karabrahimi, V.; Schwartz, J.-L.; Bellier, A.; Ha, C.; et al. Global functional analyses of cellular responses to pore-forming toxins. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chen, L.; Huang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, W.; Peng, D.; Ruan, L.; Sun, M. Bacillus thuringiensis metalloproteinase Bmp1 functions as a nematicidal virulence factor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatsenko, I.; Sinha, A.; Rödelsperger, C.; Sommer, R.J. New role for DCR-1/dicer in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity against the highly virulent bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis DB27. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3942–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.J.; McGaughran, A. The nematode Pristionchus pacificus as a model system for integrative studies in evolutionary biology. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 2380–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, R.; Riebesell, M.; Dinkelacker, I.; Wang, Q.; Herrmann, M.; Weller, A.M.; Dieterich, C.; Sommer, R.J. Isolation of naturally associated bacteria of necromenic Pristionchus nematodes and fitness consequences. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 211, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, R.; Iatsenko, I.; Witte, H.; Sommer, R.J. A subset of naturally isolated Bacillus strains show extreme virulence to the free-living nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans and Pristionchus pacificus. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 3007–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Rae, R.; Iatsenko, I.; Sommer, R.J. System wide analysis of the evolution of innate immunity in the nematode model species Caenorhabditis elegans and Pristionchus pacificus. PLoS One 2012, 7, e44255. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, R.; Sinha, A.; Sommer, R.J. Genome-wide analysis of germline signaling genes regulating longevity and innate immunity in the nematode Pristionchus pacificus. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, R.; Witte, H.; Rödelsperger, C.; Sommer, R.J. The importance of being regular: Caenorhabditis elegans and Pristionchus pacificus defecation mutants are hypersusceptible to bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Parasitol. 2012, 42, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, F.; Scheib, U.; Hu, Y.; Sommer, R.J.; Aroian, R.V.; Ghosh, P. Structure and Glycolipid Binding Properties of the Nematicidal Protein Cry5B. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 9911–9921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatsenko, I.; Corton, C.; Pickard, D.J.; Dougan, G.; Sommer, R.J. Draft Genome Sequence of Highly Nematicidal Bacillus thuringiensis DB27. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Marroquin, L.D.; Elyassnia, D.; Griffitts, J.S.; Feitelson, J.S.; Aroian, R.V. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin susceptibility and isolation of resistance mutants in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2000, 155, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg, H.; Ewbank, J.J. The genetics of pathogen avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 66, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasshoff, M.; Böhnisch, C.; Tonn, D.; Hasert, B.; Schulenburg, H. The role of Caenorhabditis elegans insulin-like signaling in the behavioral avoidance of pathogenic Bacillus thuringiensis. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, H.; Bargmann, C.I. Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2005, 438, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffitts, J.S.; Haslam, S.M.; Yang, T.; Garczynski, S.F.; Mulloy, B.; Morris, H.; Cremer, P.S.; Dell, A.; Adang, M.J.; Aroian, R.V. Glycolipids as receptors for Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin. Science 2005, 307, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Crickmore, N.; Peng, D.; Ruan, L.; Sun, M. Mining new crystal protein genes from Bacillus thuringiensis on the basis of mixed plasmid-enriched genome sequencing and a computational pipeline. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4795–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.J.; Sternberg, P.W. Apoptosis and change of competence limit the size of the vulva equivalence group in Pristionchus pacificus: A genetic analysis. Curr. Biol. 1996, 6, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampersad, J.; Khan, A.; Ammons, D. Usefulness of staining parasporal bodies when screening for Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2002, 79, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, L.J.; Huffman, D.L.; Aroian, R.V. Assays for toxicity studies in C. elegans with Bt crystal proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006, 351, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Borgonie, G.; Claeys, M.; Leyns, F.; Arnaut, G.; DeWaele, D.; Coomans, A.V. Effect of nematicidal Bacillus thuringiensis strains on free-living nematodes 1. Light microscopic observations, species and biological stage specificity and identification of resistant mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nematology 1996, 19, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Iatsenko, I.; Nikolov, A.; Sommer, R.J. Identification of Distinct Bacillus thuringiensis 4A4 Nematicidal Factors Using the Model Nematodes Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxins 2014, 6, 2050-2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6072050

Iatsenko I, Nikolov A, Sommer RJ. Identification of Distinct Bacillus thuringiensis 4A4 Nematicidal Factors Using the Model Nematodes Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxins. 2014; 6(7):2050-2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6072050

Chicago/Turabian StyleIatsenko, Igor, Angel Nikolov, and Ralf J. Sommer. 2014. "Identification of Distinct Bacillus thuringiensis 4A4 Nematicidal Factors Using the Model Nematodes Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans" Toxins 6, no. 7: 2050-2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6072050

APA StyleIatsenko, I., Nikolov, A., & Sommer, R. J. (2014). Identification of Distinct Bacillus thuringiensis 4A4 Nematicidal Factors Using the Model Nematodes Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxins, 6(7), 2050-2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6072050