Resveratrol Based Oral Nutritional Supplement Produces Long-Term Beneficial Effects on Structure and Visual Function in Human Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group (M) to the DNA base cytosine (C) from folate (B9) and B12, is most active during embryogenesis and early childhood.

- (2)

- Histone modification include protein spools that control gene expression by winding or unwinding DNA strands around histone bodies by such natural/dietary histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors as sulforaphane in cruciferous vegetables, diallyl disulfide in garlic, nigella sativa in black cumin seed oil, and resveratrol (RV) in red wine.

- (3)

- MicroRNA, short 22 base pair strands of RNA that mesh with messenger RNA, silences a segment of genes during translation. Therefore, microRNAs block the protein-making ability of gene(s). MicroRNA is called the “guiding hand of the human genome” [2].

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Selecting an Oral OTC-RV AMD Supplement with Established Bioavailability and Short-Term Efficacy

- (1)

- ↓ Inflammation (COX-2, CRP, TNF)

- (2)

- ↓ HIF-1 and VEGF genes (microRNA 21, 20b, 539)

- (3)

- ↑ Nrf2 endogenous antioxidants (glutathione, SOD, catalase) via the Nrf2 gene.

- (4)

- ↓ Blood clotting (platelet stickiness)

- (5)

- ↑ Vasodilation (nitric oxide)

- (6)

- ↑ Metal chelation (copper)

- (7)

- ↓ Oxidation, peroxidation (mega-dose increases oxidation)

- (8)

- ↓ Cell adhesion (platelets, microbes, tumor)

- (9)

- ↓ Calcification (i.e., Bruch’s membrane)

- (10)

- ↓ Bacteria, viruses, fungi

- (11)

- ↑ Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) activities via RV and vitamin D3, responsible for anti-VEGF therapy failure

2.2. Dosage and Clinical Safety Considerations

2.3. Consent/IRB

2.4. Participants

- Patient 1, a 64-year-old Caucasian glaucoma suspect with photophobia, atrophic AMD (worse right eye), and diabetes with declining vision function right eye, has been on L/RV for 2.5 years and is maintaining visual function.

- Patient 2, an 89-year-old Caucasian with chronic kidney disease and cataracts, has been on L/RV for 3 years maintaining his visual function requirements to retain his driver’s license.

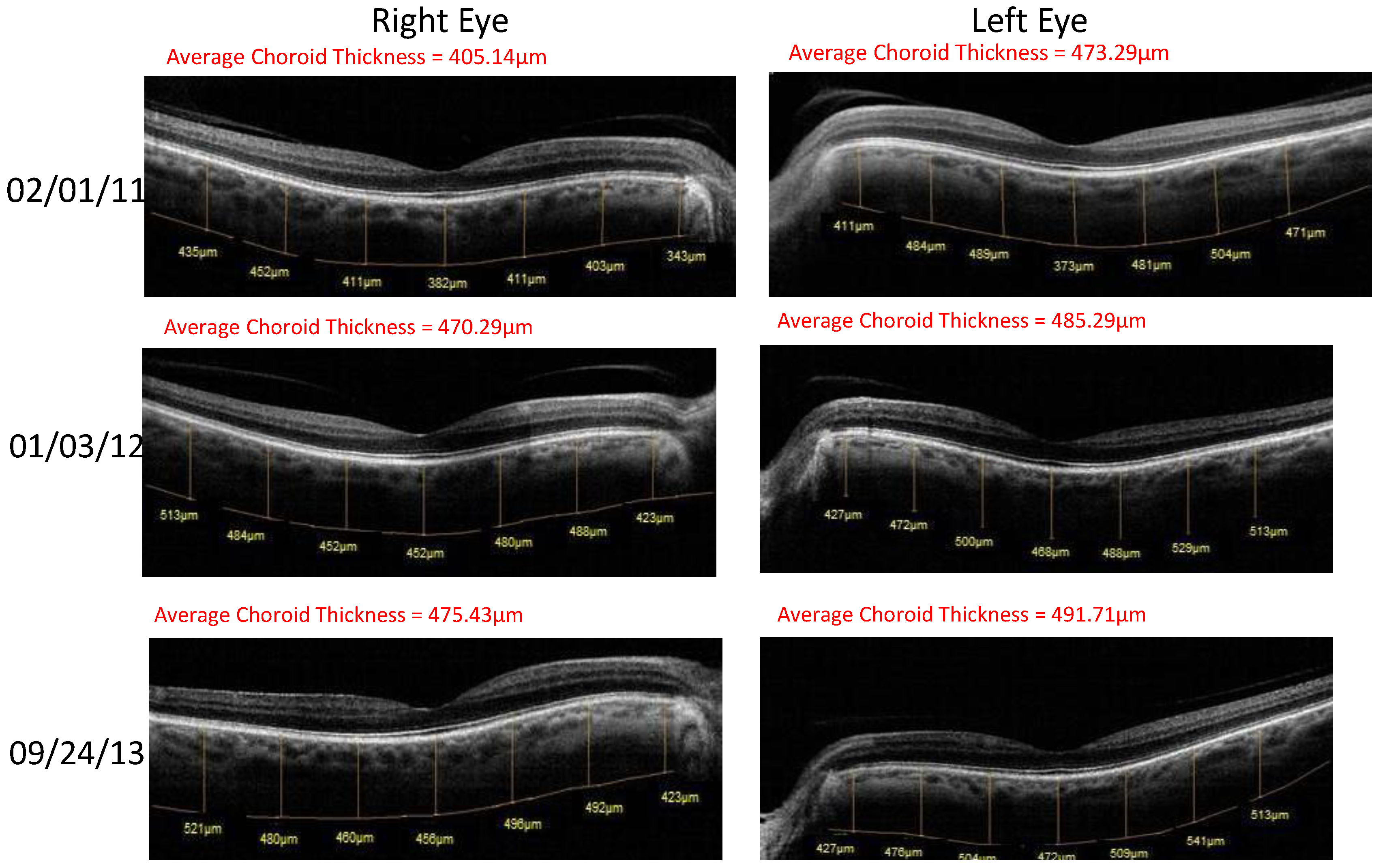

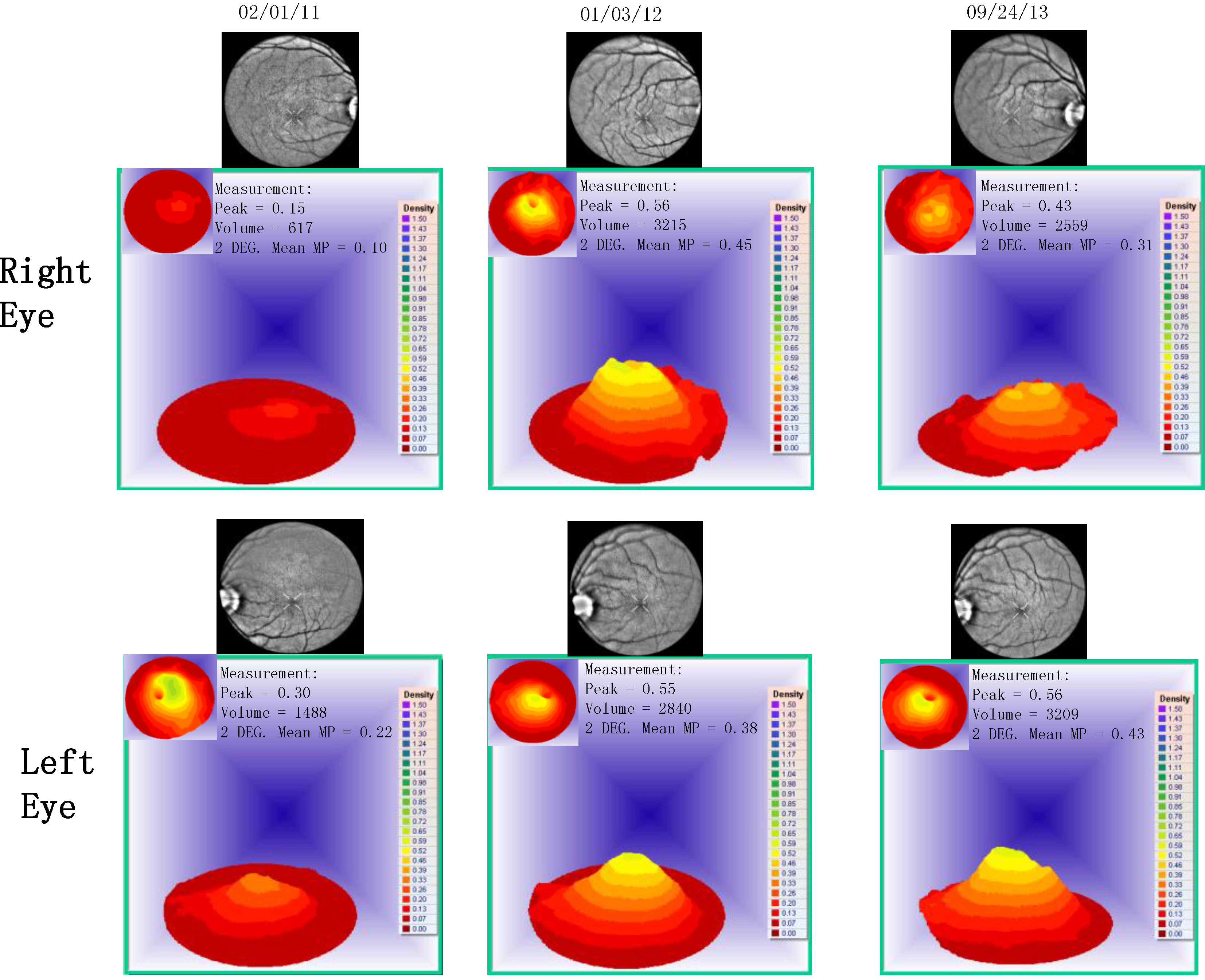

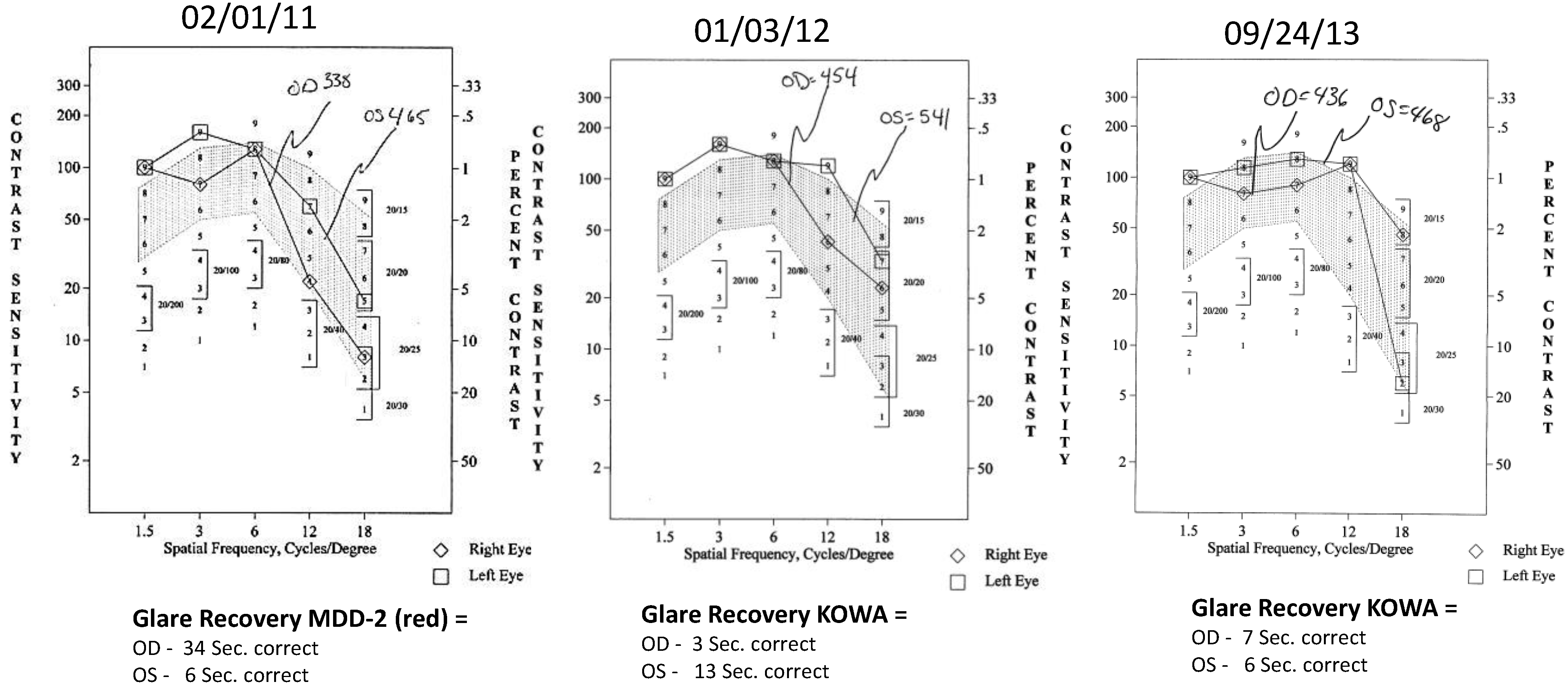

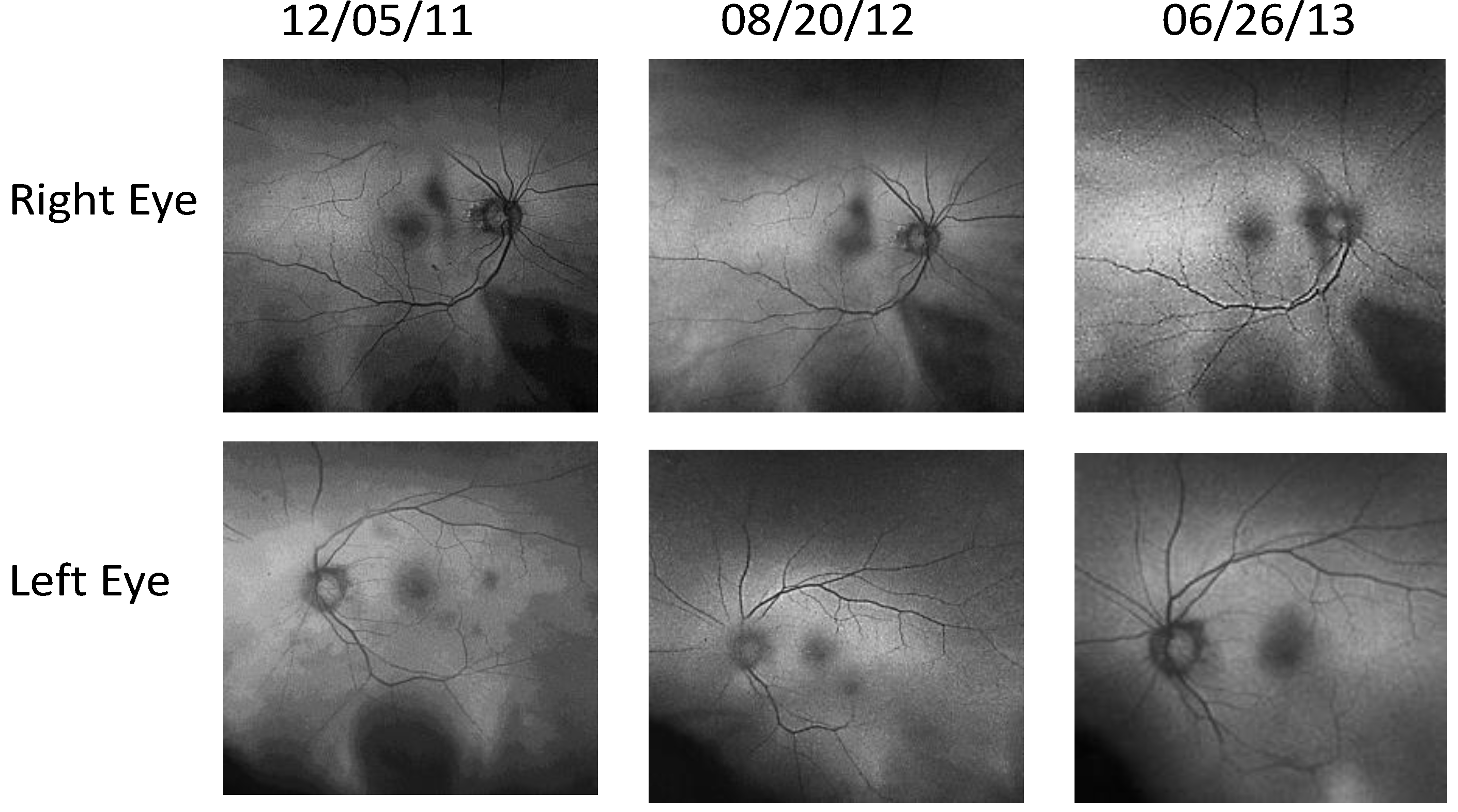

- Patient 3, a 67-year old Caucasian with bilateral Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy (PCV), a treatment resistant AMD variant, worse right eye. He also has a history of central serous retinopathy above the right optic nerve and a left retinal central foveal photoreceptor integrity line defect and impaired color vision. Improved retinal/choroid structure was observed.

2.5. Methodology

- Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) Fundus Auto Fluorescence (FAF) images were obtained with Optos® 200Tx, (Optos PLC, Dunfermline, UK), a wide-field camera that images the ocular fundus using specialized laser light. It captures a 200-degree field in one image, as compared to standard cameras that image only 50 degrees, allowing for extended evaluation. FAF images were obtained in order to identify lipofuscin granule accumulation in the lysosomal compartment of RPE cells Lipofuscin, is a mixture of autofluorescent pigments that accumulates in the RPE as a byproduct from incomplete degradation of photoreceptor outer segment, and is associated with the disease progression in AMD and retinal disease.

- Retinal Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomographic (SD OCT) images were obtained with an RTVue® instrument (OptoVue, Freemont, CA, USA). These images depict precisely aligned high-resolution in vivo histologic sagittal retinal cross sections as well as “extended-depth” choroidal vasculature cross-section images. The OCT highlights retinal alterations in morphology, structure and reflectivity, facilitating baseline and serial clinical evaluation of individual retinal layers. Using “extended depth SD-OCT” the choroid is visible. Choroid thickness decreases with age and even faster in AMD and glaucoma patients, suggestive of diminished choroidal perfusion at least partially responsible for a decline in visual function.

- Visualized macular pigment volume imaged by ARIS® (Automated Retinal Imaging System) (Visual Pathways, Inc., Prescott, AZ, USA) that also depicts retinal layers by spectral separation. We employ the spectral (visible/IR) separation images for AMD patients because, compared to traditional fundus photographs, there is high sensitivity in identifying intra-retinal pathology (retinal drusen), the critical underlying blood supply underneath the retina (i.e., the choroidal network that becomes less dense in AMD), as well as MPOD typically diminished in AMD. Traditional colored fundus photographs are also derived through wavelength recombination.

- Visual Acuity (VA—high contrast, high spatial frequency): The clinical best-refracted Snellen acuity was taken in a semi-darkened room using a digital Smart Systems® projection system (M and S Technologies, Skokie, IL, USA).

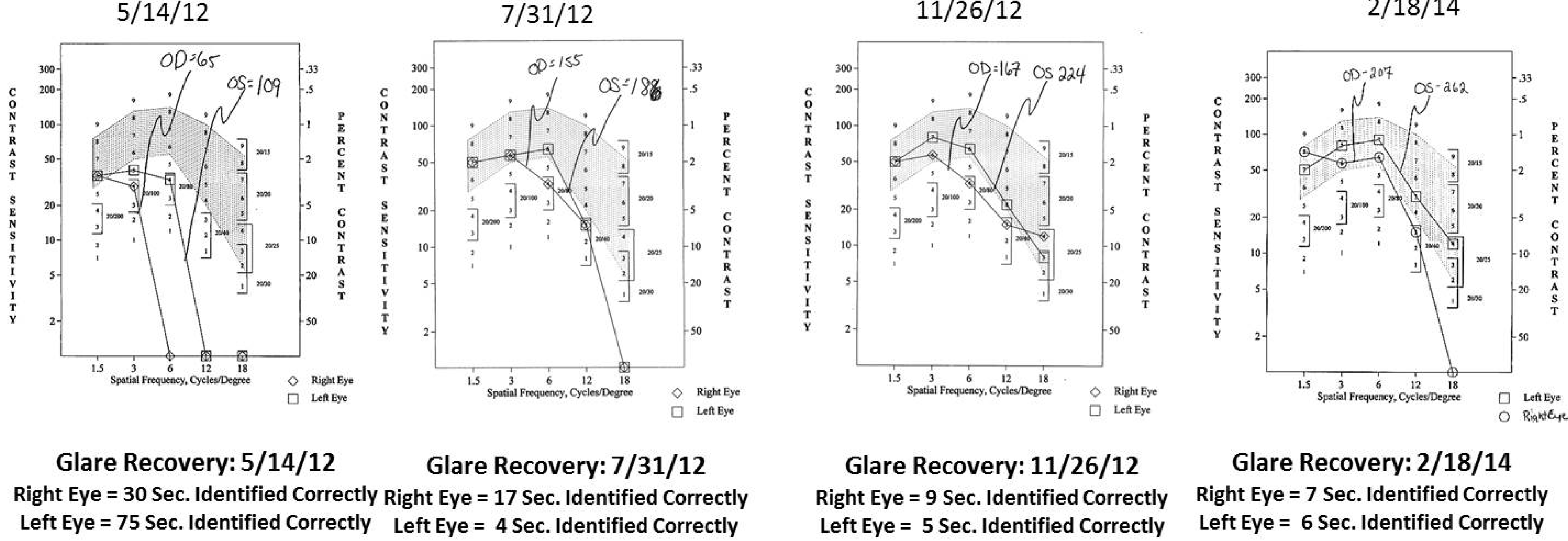

- Contrast Sensitivity (CSF—all contrasts, all spatial frequencies): The contrast sensitivity function (CSF), a measure of how an eye sees large objects (low spatial frequencies at 1.5 and 3 cycles/degree) and small objects such as Snellen letters (higher spatial frequencies, i.e., 18 cycles/degree)—x axis, at differing contrasts—y axis. The area under the curve of the resulting CSF at five spatial frequencies was measured with the validated instrument (Functional Vision Analyzer® (Stereo Optical, Chicago, IL, USA) with best refraction at each visit.

- Glare Recovery (GR—in seconds): Photo-stress cone glare recovery in seconds to a bright flash that induces retinal-RPE dysfunction was measured with a validated clinical Macular Disease Detection MDD-2® macular adaptometer (Health Research Sciences, Lighthouse Point, FL, USA).

3. Results

| Parameter | Average (SD) before Longevinex | Average (SD) While on Longevinex |

|---|---|---|

| A1C | 6.43 (0.26) | 6.07 (0.35) |

| BMI | 35.75 (0.96) | 33.88 (0.89) |

| BP-Systolic | 129.50 (4.04) | 116.13 (10.19) |

| BP-Diastolic | 76.50 (8.02) | 73.81 (6.28) |

| Pulse | 96.50 (9.33) | 86.63 (7.23) |

| Pulse-Pressure | 53.00 (7.53) | 42.31 (10.52) |

| RDW | 12.42 (1.02) | 13.95 (0.49) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juhasz, B.; Mukherjee, S.; Das, D.K. Hormetic response of resveratrol against cardioprotection. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2010, 15, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. Small RNAs: The genome’s guiding hand? Nature 2002, 420, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCay, C.M.; Crowel, M.F.; Maynard, L.A. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of the life span and upon the ultimate body size. J. Nutr. 1989, 5, 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Li, X.; Chan, N.; Hinton, D.R. Review: Epigenetic mechanisms in ocular disease. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar, K.B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Resveratrol: A multitargeted agent for age-associated chronic diseases. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 1020–1035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pervaiz, S.; Holme, A.L. Resveratrol: Its biologic targets and functional activity. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2009, 11, 2851–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bola, C.; Bartlett, H.; Eperjesi, F. Resveratrol and the eye: Activity and molecular mechanisms. Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2014, 252, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richer, S.; Stiles, W.; Ulanski, L.; Carroll, D.; Podella, C. Observation of human retinal remodeling in octogenarians with a resveratrol based nutritional supplement. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1989–2005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagineni, C.N.; Raju, R.; Nigineni, K.K.; Kommineni, V.K.; Cherukuri, A.; Kutty, R.K.; Hooks, J.J.; Detrick, B. Reseveratrol suppresses expression of VEGF by human retinal pigment epithelial cells: Potential nutraceutical for age-related macular degeneration. Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Walle, T; Hsieh, F.; DeLegge, M.H.; Oatis, J.E., Jr.; Walle, U.K. High absorption but very low bioavailability of oral resveratrol in humans. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangeetha, M.K.; Vallabi, D.E.; Sali, V.K.; Thanka, J.; Vasanthi, H.R. Sub-acute toxicity profile of a modified resveratrol supplement. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Shrinivas, K.; Bagchi, B. A stochastic chemical dynamic approach to correlate autoimmunity and optimal vitamin-D range. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itty, S.; Day, S.; Lyles, K.W.; Stinnett, S.S.; Vajzovic, L.M.; Mruthyunjaya, P. Vitamin D deficiency in neovascular versus nonneovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2014, 34, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, E.D. Therapeutic potential of iron chelators in diseases associated with iron mismanagement. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2006, 58, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurin, E.; Atanasov, A.G.; Donath, O.; Heiss, E.H.; Dirsch, V.M.; Nagy, M. Synergy study of the inhibitory potential of red wine polyphenols on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 772–778. [Google Scholar]

- Longevinex®. Available online: http://www.longevinex.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2014).

- Richer, S.; Stiles, W.; Thomas, C. Molecular Medicine in Ophthalmic Care. Optometry 2009, 80, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barger, J.L.; Kayo, T.; Pugh, T.D.; Prolla, T.A. Short-term consumption of a resveratrol-containing nutraceutical mixture mimics gene expression of long-term caloric restriction in mouse heart. Weindruch R. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.; Pratt, S.; Richer, S. Food and nutrients in disease management. In Strategies for Medical Doctors, Section I. Conditions of the Ears, Eyes, Nose, and Mouth, Age-Related Macular Degeneration, 2nd ed.; Kohlstadt, I., Ed.; CRC Press: Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fujitaka, K.; Otani, H.; Jo, F.; Jo, H.; Nomura, E.; Iwasaki, M.; Nishikawa, M.; Iwasaka, T.; Das, D.K. Modified resveratrol Longevinex improves endothelial function in adults with metabolic syndrome receiving standard treatment. Nutr. Res. 2011, 12, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longevinex® for Life. Available online: http://www.longevinex.com/articles/longevinex-first-red-wine-anti-aging-capsule-to-pass-sub-acute-toxicity-testing (accessed on 5 May 2014).

- Richer, S. A protocol for the evaluation and treatment of atrophic age-related macular degeneration. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1999, 70, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esmaeelpour, M.; Ansari-Shahrezaei, S.; Glittenberg, C.; Nemetz, S; Kraus, M.F.; Hornegger, J.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Drexler, W.; Binder, S. Choroid, Haller’s, and Sattler’s layer thickness in intermediate age-related macular degeneration with and without fellow neovascular eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 5074–5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, E.H.; Khanna, A.; Tucker, B.A.; Abràmoff, M.D.; Stone, E.M.; Mullins, R.F. Structural and biochemical analyses of choroidal thickness in human donor eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Ahsan, K.; Bagchi, A.; Pacher, P.; Das, D.K. Restoration of altered microRNA expression in the ischemic heart with resveratrol. PLoS One 2010, 5, e15705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Das, S.; Ahsan, M.K.; Otani, H.; Das, D.K. Modulation of microRNA 20b with resveratrol and longevinex is linked with their potent anti-angiogenic action in the ischaemic myocardium and synergestic effects of resveratrol and γ-tocotrienol. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 2504–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhasz, B.; Das, D.K.; Kertesz, A.; Juhasz, A.; Gesztelyi, R.; Varga, B. Erratum to: Reduction of blood cholesterol and ischemic injury in the hypercholesteromic rabbits with modified resveratrol, longevinex. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2011, 348, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanGiovanni, J.P.; Chew, E.Y. Clinical applications of age-related macular degeneration genetics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a017228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsche, L.G.; Chen, W.; Schu, M.; Yaspan, B.L.; Yu, Y.; Thorleifsson, G.; Zack, D.J.; Arakawa, S.; Cipriani, V.; Ripke, S.; et al. Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richer, S.; Patel, S.; Sockanathan, S.; Ulanski, L.J., II; Miller, L.; Podella, C. Resveratrol Based Oral Nutritional Supplement Produces Long-Term Beneficial Effects on Structure and Visual Function in Human Patients. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4404-4420. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6104404

Richer S, Patel S, Sockanathan S, Ulanski LJ II, Miller L, Podella C. Resveratrol Based Oral Nutritional Supplement Produces Long-Term Beneficial Effects on Structure and Visual Function in Human Patients. Nutrients. 2014; 6(10):4404-4420. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6104404

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicher, Stuart, Shana Patel, Shivani Sockanathan, Lawrence J. Ulanski, II, Luke Miller, and Carla Podella. 2014. "Resveratrol Based Oral Nutritional Supplement Produces Long-Term Beneficial Effects on Structure and Visual Function in Human Patients" Nutrients 6, no. 10: 4404-4420. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6104404