1. Introduction

While the concept of development mainly looks to reconcile economic growth with increasing wealth quality indicators, sustainable development looks to align economic growth with economic independence, social justice, and the conservation of natural resources [

1]. According to an analysis by Koroneos and Rokos (2012) [

2], despite innumerable efforts to promote sustainable development around the world, more than 20% of the world’s population lives on less than one US dollar per day, 70% of whom work and live in rural areas. Therefore, the development of effective projects aiming at sustainable development and poverty eradication, especially in agricultural countries like Brazil, must be implemented in rural areas [

3].

In this framework, solidarity economy organizations provide an alternative in relation to the contemporary model of economic development, offering more opportunities and better quality of life, while also preserving the environment and natural resources [

4]. Recent studies show that solidarity organizations have had a positive impact on sustainable development in low-income economies around the world, achieving a variety of outcomes, such as social innovation, preservation of natural resources, economic autonomy, and social transformation [

4,

5,

6,

7]. As described by Koroneos and Rokos (2012) [

2], the concept of Worth-Living Integrated Development can be reached only through a commitment to building a better world, based on human values of peace, justice, solidarity, democracy, and political, economic, and social ethics, including the conservation of nature and valuing of cultural identities. These aspects are extremely relevant in the evaluation of SEROs acting as alternative paths for sustainable development and the maintenance of local people in rural areas.

In Brazil, the principles of solidarity economy were defined in 2003 in the Brazilian Declaration of Solidarity Economy Principles [

8], and focused on five main concepts: (1) social valorization of people’s work; (2) full satisfaction of people’s needs through technological creativity and economic activity; (3) recognition of women as having a fundamental place in the solidarity economy; (4) promotion of a respectful relationship with nature; and (5) values of cooperation and solidarity. Brazilian public policies, through various programs such as Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos (Food Procurement Program, PAA) and the Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar (National School Meal Program, PNAE), among others, guide the development of SEROs and how they are integrated across a region. These policies are created by the Federal Government, but executed and coordinated by municipalities, enabling SEROs to retain local and regional characteristics.

However, the fostering of SEROs as a means to support rural development has occurred only recently. During the military government (1964–1985), Brazilian agrarian policy basically consisted of the opening up of the Amazon region and the establishment of farmers on public lands. Since the late 1980s, through the political process of democratization and the enactment of the New Constitution in 1988, new opportunities were created for historically marginalized social groups, including small-scale family farmers. In the 1990s, rural development focused on new policies for agrarian settlements, land reform, and access to credit for small-scale family farmers. The main achievement was the creation of the National Program for the Enhancement of Family Farming (PRONAF) in 1995, which was the first agricultural policy to effectively recognize the specific characteristics of family farming. Nevertheless, significant changes in rural development have taken place since the year 2000, with special attention given to food security, improvement of existing programs, and the implementation of news programs, such as: Food Procurement Program (PAA), Program of support to family agroindustry and the National Program for the Production and Use of Biofuels, among others [

9].

In 2013, the participants of the 2nd National Conference on Sustainable and Solidarity Rural Development, agreed that is was necessary for sustainable rural development “to strengthen integration between the countryside and the city based on solidarity, sustainability and cooperation, such as associations, solidarity cooperatives, fairs, fair trade and solidarity, among others” [

10] (p. 37). Overall, working towards social impact and sustainability goals results in greater value placed on solidarity organizations which can consequently improve local economies [

11]. As mentioned above, solidarity economy organizations are guided by social and solidarity values, and unlike traditional entrepreneurial organizations, their objectives are linked to social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors in a different way than traditional entrepreneur organizations [

12]. Thus, the indicators used to evaluate their performance must carefully assess their objectives and organizational interactions and how the objectives are linked to a variety of local and global factors [

13].

The process of measuring and/or evaluating performance in solidarity economy organizations encourages improvement and provides direction on how to achieve the organization’s mission [

14]. As with other non-profit organizations, this is a complex process because the outcomes are often unquantifiable [

15], making them difficult to measure, and it is complicated by the difficulty of converting qualitative data related to social goals into quantitative metrics [

16]. Herman and Henz (2008) [

17] argue that the effectiveness of nonprofit organizations is a multidimensional social construction and as such there are no universally applicable best practices.

Performance can be evaluated in many different forms, both in terms of the methodologies used and the nature of the information analyzed, and can be adapted to different objectives and organizational activities, and cultural and territorial features, among others. There are several studies in the literature that present a variety of approaches to addressing performance measurement in social and/or non-profit organizations, including: Kaplan (2001) [

18] and Greiling (2010) [

19] who approach performance measurement from the perspective of the Balanced Scorecard; Straub, Koopman and Van Mossel (2010) [

20], Ebraim and Rangan (2014) [

21], and Maclndoe and Barman (2013) [

22] who employ models and frameworks based on logic models or a conceptual systems approach. However, only a few studies specifically address the solidarity economy, including: Bellucci et al. (2012) [

23] using a model based on multicriteria methods, and Cançado, Vieira and Cançado (2011) [

24] and Socias and Horrach (2013) [

12] who apply other models and frameworks.

The objective of this study is to present a theoretical model that provides indicators to evaluate the performance of Solidarity Economy Rural Organizations in Southern Brazil based on the perceptions of decision makers within these organizations. We provide information about SEROs established in the Southwest region of Paraná State, and their close engagement with sustainable rural development, and we also discuss the development of further studies, administrative tools and models to evaluate SERO performance. We expect that the results presented will contribute to SEROs improvement, and consequently support the organizations’ goals to achieve sustainable rural development in the surveyed region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location/Sample Site

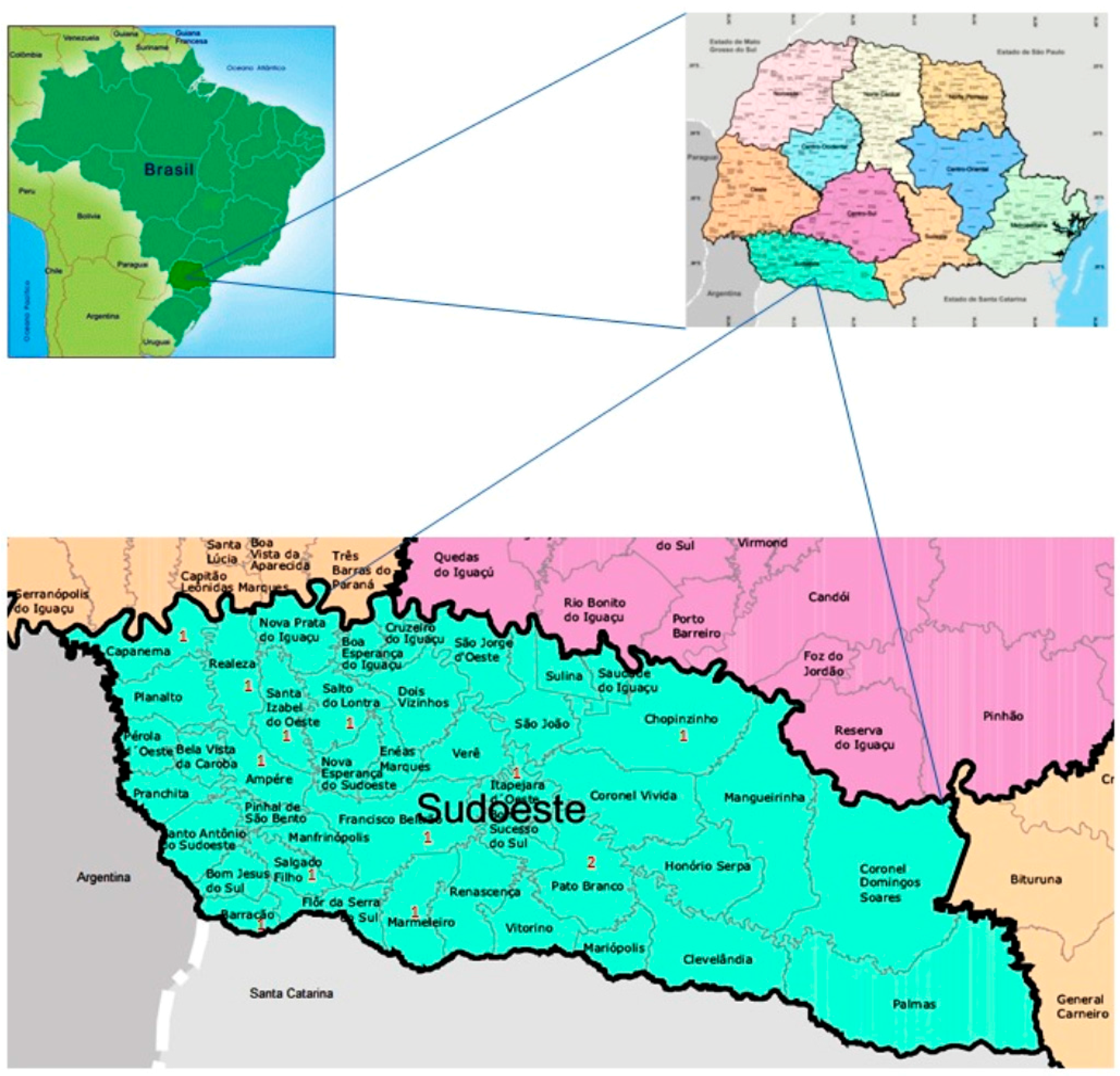

The study involved the administration of a questionnaire to representatives of SEROs who were acting in the Southwest Region of Paraná State, Southern Brazil. According to a survey performed in 2013 [

25], this region has the highest concentration of SEROs activity of Paraná State (30.46%). This region is bordered by the Iguaçu River, with the Argentinian border to the west, and Santa Catarina State to the south (

Figure 1).

With an estimated population of 620,000 habitants [

28], Southwest Paraná State includes 42 municipalities distributed across an area of 17,060 km

2 (about 8.5% of the state’s territory). In this mesoregion, agriculture is the most important economic activity, followed by the forestry sector (97.4% of area) [

29]. Farms are mostly small, family owned properties of less than 100 hectares (72.7% of area) [

30], and as such, SEROs play an important role in supporting the maintenance of families in rural areas.

To identify the active SEROs in the survey region, we used The Solidarity Economy Tracker Tool, a search engine that was launched in 2003 at the Brazilian Forum of Solidarity Economy. The tool lists the solidarity organizations and main products and services offered [

31]. To build the research sample, only solidarity organizations operating in rural areas (SEROs) were considered.

The Solidarity Economy Tracker Tool identified 93 SEROs in the studied region, highlighting the adherence to the ideologies of association and cooperation. Of those identified, 32 organizations were found to be inactive, three could no longer be classified as solidarity economy organizations, and 34 were inaccessible (non-existent or incorrect phone number or address). Of the 24 accessible and active identified SEROs, only 13 were able to answer the questionnaire satisfactorily in the given timeframe. Among these 13 SEROs, two (SERO 3 and 4) were represented by the same person; therefore, only 12 questionnaires were considered during the analysis of Blocks II and III of the questionnaire. These 13 SEROs assist approximately 2000 stakeholders distributed across 12 municipalities, in which more than 300,000 citizens live [

28]. The stakeholders work mainly on the family farmers system, devoted to food production for the local market. This sample size of 13 SEROs represents about 50% of active organizations.

2.2. Data Collection

This study presents a descriptive and qualitative theoretical model as it seeks to understand actual processes and causal relationships, and to provide elements of response to the questions arising from a process, without aiming at a single, true solution. Data was collected through survey interviews conducted between May and July 2016, aiming to understand what the representatives of SEROs consider important in their performance evaluation process. The survey was structured in three blocks, as follows:

Block I: SERO Identification. This block identifies the representative of the organization and briefly characterizes the organizational structure.

Block II: Importance of criteria. In this block, several performance evaluation criteria were listed across six dimensions. The respondents attributed a degree of importance for each criterion using the Likert scale [

32]: (1) not important; (2) somewhat important; (3) indifferent; (4) important; (5) very important; and (6) unable to answer.

Block III: Suggestions from surveyed organizations. In this block, the respondent was given the opportunity to suggest other criteria and evaluation dimensions not listed in Block II that they consider relevant based on experience.

During SERO characterization (Block I), the representatives were asked to list the main products marketed by their organizations, grouped into five categories: vegetable, fruit, meat and eggs, processed products, and others. The vegetable category included all types of leafy vegetables, roots, tubers and potatoes. The fruit category only included unprocessed fresh fruit. All types of meat and eggs were included in that category, and within processed products, we included all products that are processed in some way. The others category encompassed all products not included in the previously defined categories.

After a brief characterization of the organization, the next stage of the survey (Block II) sought to validate the performance evaluation criteria presented by the questionnaire. The research tool was based mainly on the common principles of the solidarity economy as presented by Fórum Brasileiro de Economia Solidária (FBES) [

8], and in recent studies [

19,

20,

22,

23,

24]. These principles led to the development of several criteria, grouped into six evaluation dimensions: (1) legal documents and standards; (2) valuing of human work; (3) technology and economy; (4) acknowledgment of women; (5) preservation of and respect for nature; and (6) cooperation and solidarity.

The legal documents and standards dimension encompasses the legal processes of a formally registered cooperative or association. This includes registrations, such as the Brazilian National Registry of Legal Entities (CNPJ), state registration, by laws, internal regulations and mandatory books, among others. In some cases, legal registrations are mandatory for the organization to participate in governmental programs. However, not all forms of solidarity economy organizations have the same requirements.

The valuing of human work dimension represents the values that each organization attributes to knowledge, participation, and work of their associates. This dimension highlights the importance of human development within the organizations and community. The associates’ educational backgrounds are considered, as well as their knowledge based on previous experience, and how the organization contributes to the creation of new knowledge and experiences.

Technology and economy dimension include criteria related to an organization’s economic outcomes and the returns it provides to its associates. Although these organizations are nonprofit, it is important to maintain a balance between social objectives and economic outcomes [

33]. The acknowledgment of women dimension involves discussion around the participation of women as associate rural workers and as directors in the organizations. Waltz (2016) [

34] assessed the evaluation of gender empowerment in rural areas of Brazil and notes that despite improvements, women’s work is not properly recognized and men continue to be responsible for decision-making and external relations. As such, our study considered criteria that focused on the integration of rural women into the management of the family and the organization.

The preservation of and respect for the nature dimension is directly linked to the maintenance and protection of environmental integrity and its natural resources. Thus, this dimension relates to meeting current production demands without compromising the environment for future generations. The criteria include awareness of correct garbage disposal, the importance of organic production as an alternative for agriculture and the organization’s responsibility as a member of the solidarity economy in the conservation of natural resources.

The cooperation and solidarity dimension is a key aspect of the investigated organizations. As solidarity economy presupposes cooperation and solidarity amongst associates and integration with the community in which they operate. According to Bhattacharyya (2004, p. 14) [

35] “solidarity demands that we feel a concern for every person in the nation and the world as a whole (the solidarity of the species), extending solidarity to people we do not know”. Therefore, this dimension represents the evaluation criteria related to ease of accessing an organization’s documents, and to commitment and solidarity among associates.

In Block III the SERO representatives were free to make any suggestions in relation to evaluation criteria.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using an electronic spreadsheet. The gathered data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, mainly measures of absolute frequency, which are useful for describing discrete variables with small variation intervals and few differing values, such as the Likert Scale [

36], and synthetic measures. We considered the criteria that presented an absolute frequency above 6 in options 4 (important) and 5 (very important) as validated. The suggested criteria were assigned to one of the six dimensions.

Only the main products identified in Block I were used to characterize the SEROs in terms of production volume. Other vegetables not listed in

Table 1, but produced and commercialized by SEROs, were recorded separately.

3. Results

3.1. SEROs Characterization

The analysis of SERO characteristics showed that the majority operate as cooperative systems (10 SEROs or 77%), while two of them are run as associations (15%), and only one was categorized as another system (commission). In relation to the length of time acting in the region, just one SERO has operated for more than 20 years, while six SEROs have been running between 10 and 15 years, and another six have operated in the region for up to 10 years.

Figure 2 presents the activities developed by the surveyed SEROs. Based on the SEROs representative’s perception, the main activities are linked to processed products, which was mentioned by 62% of respondents. The category with the lowest responses was meat and eggs, which was mentioned by only 23% of respondents.

Table 1 presents the products marketed by the surveyed SEROs, organized into seven categories. Of the seven product categories evaluated, vegetable products was the category with the greatest diversity of products, with 19 different products cited, followed by processed products, with 17 products cited. Coffee, sugarcane, and fruit juices were listed by just one SERO, which operates in open-air markets, selling a wide variety of beverages.

3.2. Validation of Performance Evaluation Criteria

The six dimensions described include 36 criteria assessed for their degree of importance by the 12 respondents representing 13 SEROs. Of the 432 responses, 414 indicated the criteria as being important or very important. This data supports the relevance of these criteria for those who experience and work in the reality of SEROs.

In relation to legal documents and standards, listed in

Table 2, we can verify the importance of including these criteria in SERO performance evaluation processes to ensure the continuation of their activities, since many resources and the funding received by these organizations are based on performance in this dimension. Despite the wide scope of legal documents and standards, all representatives surveyed consider these criteria to be important or very important. The criteria of “having municipal registration and a charter” and “having internal regulations” were considered as somewhat important and indifferent, respectively, by one of the respondents; the criteria of “having a structured and active fiscal board” was considered somewhat important by another respondent.

As shown in

Table 3, we can see the perception of SERO representatives in relation to the valuing of human work in the performance evaluation process. The results suggested that most of the respondents consider these five criteria as important or very important. However, one SERO representative considered four of the five criteria indifferent for the performance evaluation process and only other one SERO representative considered one criteria as indifferent.

The survey evaluated the importance of seven criteria in relation to technology and economy.

Table 4 shows that the respondents predominantly considered the criteria important or very important. The existence of an administrative fee was the most controverted criteria, and was considered somewhat important or indifferent by three respondents, and very important to three representatives. Furthermore, one respondent that was indifferent to the existence of an administrative fee also considered the criteria of regular presentation of management reports as indifferent. Moreover, the maintenance of a database identifying the producers and their products was considered somewhat important by another respondent.

The criteria related to women acknowledgment, in management and decision making, and their perceived importance in the performance evaluation process, are shown in

Table 5. In the survey, one of respondents commented that this theme always brought about much deliberation, and it is better for organizations not to engage in this debate. This experience demonstrates that although these criteria are considered by representatives as mainly very important or important, none of the interviewees are female, and the organizations consider themselves exempt from the recognition of gender equity. Additionally, two criteria related to the incentive and recognition of women in the organization were ranked as indifferent in the evaluation process by two different SEROs.

Table 6 presents the SERO representatives’ perceptions regarding the importance of preservation of and respect for the environment. This dimension is critical to sustainable rural development. As with other evaluate dimensions, most of the respondents regarded the criteria as very important or important in performance evaluations. However, when asked about subjects related to pesticides, one respondent expressed the insignificance of recommendations focused on the correct disposal of pesticide packaging. According to this SERO representative, who works with organic products, there is no need to assess awareness about the correct disposal of pesticide packaging for organizations that produce organic products.

In relation to cooperation and solidarity, presented in

Table 7, the results indicate that all respondents expressed their view of the importance of the included criteria. Two respondents regarded the assessment of ways to organize mutual help as indifferent. These responses demonstrate strong adherence to the concept of solidarity in the organization’s philosophy.

3.3. Suggestions from Organizations

After ranking the importance of the criteria presented in the questionnaire, the participants had the opportunity to contribute suggestions for criteria and dimensions they considered important but that were not included in the survey. In addition, participants could suggest the exclusion of criteria and dimensions they considered unimportant.

Table 8 summarizes the suggestions presented by the respondents.

The representatives of SEROs 6, 8, 10 and 11 did not suggest the inclusion of new criteria. None of the respondents suggested the exclusion of existing dimensions or the inclusion of new ones, thus supporting the division of criteria into dimensions as presented in Block II of the survey. Nine new criteria were suggested, demonstrating the need to go beyond the criteria reported in the literature and to consider the perspectives of those involved in these organizations.

Moreover, in opening the survey to any comments that respondents wished to make, the representative of SERO 2 commented that the entry of new members is approved in a forum of the associates, and the representative of SEROs 3 and 4 suggested a few criteria that he considered similar. Furthermore, the representative of SERO 5 observed that, due to several unsuccessful attempts, solidarity economy organizations are not well regarded in society, which is an issue that the organizations need to address. The representative of SERO 8 mentioned the lack of people with the necessary background to train human resources in the organizations and those that are available either do not focus on the solidarity economy or charge fees that are unfeasible for the organizations. The representative of SERO 11 also commented on the lack of trainers qualified to address solidarity economy organizations as well as the lack of proper governmental support not only in financial terms, but also at the municipal, state, and federal levels. Finally, the representative of SERO 13 mentioned the need for partnerships with universities and institutes in terms of research and extension that can support the development of activities in these organizations.

4. Discussion

In Brazil, the first solidarity economy initiatives that gave rise to SEROs began in the 1970s with the development of popular cooperatives to confront economic and social crises. In the 1990s, the movement gained force. From the 2000s onward, this system was restructured when left-leaning representatives from the working classes helped to elect the Brazilian president. At that time, the perception of the viability of solidarity economy experiences and the potential to bring about many benefits, not only to their members but also to wider society, led the Brazilian Government to promote cooperative systems as a means of generating profit and social cohesion across the country [

37,

38]. Current Brazilian public policies are executed and coordinated at the municipal level through financial transfers from the federal government, thus allowing regional diversity to be incorporated into solidarity economy entities.

As shown in

Figure 2, the activities of SEROs are diverse and mainly related to food production. As recognized by Schneider and Niederle (2010) [

39], the diversity of SEROs production is directly related to the struggle for family farm autonomy, and contributes to social, economic and cultural development strategies. Additionally, the respondents engaged in fruit production stated that the supply of some products fluctuates throughout the year due to seasonality and regional climatic characteristics, aspects that negatively affect the consolidation of these activities.

Of the six dimensions evaluated, the representatives attributed greater relevance to technical and legal regulatory aspects than solidarity and humanitarian criteria. The results show that most of the respondents considered the 36 criteria mostly important or very important. Four out of five criteria were considered indifferent to the performance evaluation process by at least one of the respondents. This scenario reinforces the importance of studies and tools that approach performance evaluation from the principles of the solidarity economy, with the goal of assessing these principles in an equitable way. Our results confirm that the representatives perceive the importance of evaluating support for human work. However, we note that there is a greater emphasis on the importance of criteria related to technical development than those related to solidarity economy, self-management, or the management of associates.

The validation stage of the proposed criteria carried out in this study was important to assess the perception of SERO representatives in relation to their reality. The process shows the willingness of organizations to evaluate their performance and attain the principles of the solidarity economy. It is important to point out that each respondent answered based on their actual experience, demonstrating the need to consider the perspectives of the organizations in the development of performance evaluation processes and instruments, thus highlighting the importance of this study in this context. Our results also support the premise of the Intercontinental Network for the Promotion of Social Solidarity Economy (RIPESS) [

40], that suggests the contribution of SEROs to their evaluation in a range of outcomes, including: their impact on local, national, and international development, the creation of permanent employment, the development of new services and improved standards of living, their contribution to equality, the protection of the environment and the ethical creation of wealth. All of these factors are integrated into the principles of Solidarity Economy Organizations.

In relation to perceptions about Dimension 1 (Legal Documents and Standards), the results show a concern for the evaluation and compliance with legislation; these are important factors for the sustainable maintenance of organizations despite the high cost related to such procedures. In Dimension 2 (Valuing of Human Work), with the exception of one SERO that responded indifferent to four of five criteria presented, all others validated the relevance of criteria related to developing human labor. Additionally, we noticed a greater emphasis on technical development criteria than on those related to solidarity economy, self-management, or the benefits of association.

In the technology and economy dimension, the data suggest that greater relevance is attributed to evaluation criteria related to controls, than criteria linked to valuing the participation of associates, such as the presentation of administration reports. For the women acknowledgment dimension, respondents acknowledged the importance of improvements related to the process of gender integration as part of the solidarity economy principles in the local community. The results observed in this survey were similar to those discussed by Waltz (2016) [

34] who discussed various ways in which the women are disempowered and lack autonomy.

In terms of nature preservation, the fact that one of the respondents mentioned that is it not necessary to evaluate if pesticides are correctly disposed of because the production is organic, suggest that predatory and unsustainable agricultural practices continue, even in the context of family agriculture, an issue also mentioned by Paulino (2014) [

41]. On the other hand, these criteria were considered relevant and validated by the other SEROs. Although the correct disposal of pesticide packing has a cost and is time consuming, it is carried out by SEROs to ensure compliance with Brazilian regulations. Compliance with the legislation in a context of non-organic production is extremely relevant to the preservation of and respect for nature dimension.

In relation to cooperation and solidarity, the two SEROs that perceived the criterion “existence of ways to organize mutual help if a producer is unable to work” as indifferent reinforces the relevance of performance evaluations based on the principles of the solidarity economy. Such an evaluation can assess the way in which SEROs are, or are not, achieving these principles.

Of the six evaluated dimensions, the results show a gap between the academy and the practice, which can be filled by universities and research institutions. This study demonstrates that the analyzed organizations understand performance evaluation that considers the principles of solidarity economy as relevant, and such a process enables the continuous improvement of these indicators. Measurements of performance can improve and stimulate organizations to achieve their mission [

14]. In general, as well as validating the proposed criteria, the suggestion of new criteria to be considered in the creation of performance evaluation instruments transforms the evaluation into a collective and democratic process. Similar experiences are being developed in other countries; for example Social Market Aragón, Spain, had their Social Balance Impact evaluated based on social and solidarity economy principles [

42], from which further indicators and instruments have been developed since it was first conducted in 2014.

5. Conclusions

The organizations discussed herein consider it relevant to evaluate performance based on criteria from the principles of the solidarity economy. Moreover, the results show a greater concern for criteria related to legal demands than for criteria related to the valuing of human work, as well as a greater interest in evaluating technical aspects rather than solidarity aspects. Additionally, due to the predominance of males within the SEROs administration, the surveyed data demonstrate the need for improved tools related to gender equity, as these principles are integral to achieving solidarity economy in rural areas.

Our results show the validity of the performance evaluation criteria proposed in the research instrument. Of the 12 SERO representatives, only four did not suggest new evaluation criteria. This demonstrates interest and the representatives’ ability to compromise with the enterprises that are involved. This compromise strengthens the solidarity economy enterprises and also contributes to sustainable development of the territory.

This study contributes to the understanding of the role of Solidarity Economy Organizations in sustainable rural development and provides a foundation on which to collectively and democratically develop performance evaluation processes and tools, based on the solidarity economy principles established in Brazil. The analysis represents an important academic contribution when we consider the gap between the academy and the practice, which can contribute significantly to the development of future studies on the topic.

A limitation of this study is that it only included one region. We therefore suggest that future work expands the scope of the research, applying it to other areas in Paraná State and across Brazil, using the background presented here to develop processes and performance evaluation models applicable to other organizations.