The Role of Company-Cause Fit and Company Involvement in Consumer Responses to CSR Initiatives: A Meta-Analytic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Company-Cause Fit and Its Types

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Company-Cause Fit and CSR Attributions

3.2. Company-Cause Fit and Consumer Outcomes of CSR Initiatives

3.3. The Moderating Role of Company Involvement

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Selection of Studies and Sample Characteristics

4.2. Statistical Procedure

5. Results

5.1. Hypothesis Tests

5.2. Supplementary Analysis

6. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Product Type/Company | Cause/Charity | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barone, et al., 2007 [23] | apparel brands | nature conservation | students |

| Becker-Olsen, et al., 2006 [18] | Home Depot, Revlon | homelessness, domestic violence | students |

| Becker-Olsen, Hill 2006 [62] | Alpo Petfoods, Sport Authority | Humane Society, Special Olympic | students |

| Bower, Grau 2009 [63] | early learning tools | early literacy, childhood obesity | students |

| Buil, et al., 2012 [64] | printer, mp3, pasta, chocolates | Red Cross, Greenpeace | consumers |

| Chéron, et al., 2012 [65] | pet-toy | cruelty to animals, AIDS | students |

| Das, et al., 2016 [66] | coffee drink, toothpaste | Coffee Kids, Oral Health America | students |

| Ellen, et al., 2000 [67] | grocery store, building supply store | disaster, ongoing cause | consumers |

| Ellen, et al., 2006 [31] | gas station | older and disabled people, wildlife habitats, homelessness | consumers |

| Gu, Morrison 2009 [68] | timber based furniture manufacturer, Hewlett-Packard | early literacy, childhood obesity, recycling, cleaning the Everest | students |

| Gupta, Pirsch 2006 [44] | Disney entertainment park, AT&T, MCI WorldCom | St Jude Children’s Research Hospital | students, consumers |

| Ham, Han 2013 [69] | hotel | green practice | consumers |

| Han, et al., 2013 [70] | Adidas, Nike, Hyundai Motors, Samsung Electronics | World Cup | consumers |

| Kerr, Das 2013 [71] | chocolates | Children’s Hunger Fund, Save the Whales | students |

| Kim 2011 [72] | computer technology company | education for low-income families, transportation for older and disabled people | students |

| Kim, Kim 2016 [73] | movie tickets | Not revealed | students |

| Kim, Sung, Lee 2012 [29] | construction company | Habitat for Humanity, Magpie Nest, Red Cross, Society for Cerebral Palsy | students |

| Koschate-Fischer, et al., 2015 [74] | mineral water | natural environment, abused dogs | students |

| Kuo, Rice 2015 [75] | candies, lemonade | Susan G. Komen Foundation, leukemia | students |

| Lafferty 2007 [76] | shampoo | American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Save the Whales | students |

| Lafferty 2009 [77] | shampoo | National Cancer Institute, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals | students |

| Lafferty, et al., 2004 [10] | mineral water, instant soup | Red Cross, Famine Relief | students |

| Lee, Ferreira 2013 [78] | t-shirt | Boys and Girls Club, Pop Warner Football League, Human Rights Campaign, Planned Parenthood | students |

| Menon, Kahn 2003 [26] | orange juice, pet foods | cancer, skin cancer, homelessness, green forests | students |

| Myers, Kwon 2013 [41] | Ralph Lauren, Converse | Habitat for Humanity, Red Cross | students |

| Myers, et al., 2012 [37] | clothes | water conservation | students |

| Nan, Heo 2007 [79] | orange juice | Healthy Diet Research Association, Traffic Safety Research Association | students |

| Pirsch, et al., 2007 [13] | food producer | environmental causes, breast cancer | students |

| Rifon, et al., 2004 [80] | shoes, medicines | contraception | students |

| Rim, et al., 2016 [81] | pharmaceutical company | St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, United Cerebral Palsy Association, Humane Society | students |

| Robinson, et al., 2012 [25] | notebook | education, water conservation | students |

| Samu, Wymer 2009 [82] | Gerber | Save the Children, National Wildlife Federation | students |

| Samu, Wymer 2014 [83] | bookstore | environment conservation, education | students |

| Seok Sohn, et al., 2012 [84] | milk brand | clean water for African children | students |

| Simmons, Becker-Olsen 2006 [28] | pet foods | Paralympic games, animal protection | students |

| Van den Brink, et al., 2006 [45] | trousers, staples | pollution in rivers, living conditions of poor iron or cotton suppliers of the company | students |

| Westberg, Pope 2005 [85] | soft drinks | homelessness | students |

| Yang, et al., 2015 [86] | cosmetics company | animal testing | students |

| Yoon, et al., 2006 [17] | tobacco company, oil company | lung cancer, natural environment | students |

References

- Lii, Y.S.; Wu, K.W.; Ding, M.C. Doing good does good? Sustainable marketing of CSR and consumer evaluations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate social responsibility. In Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.S.; Lee, M. Doing right leads to doing well: When the type of CSR and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Speed, R. Linking sponsorship and cause related marketing: Complementary and conflicts. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 1361–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanska, M.; Nestorowicz, R. (Eds.) Fair Trade in CSR Strategy of Global Retailers; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagawa, S.; Segal, E. Common interest, common good: Creating value through business and social sector partnerships. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Hult, G.T.M. The impact of the alliance on the partners: A look at cause-brand alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Company associations and corporate consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsch, J.; Gupta, S.; Grau, S.L. A framework for understanding corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Rita, P.; Trigueiros, D.A. Text Mining-Based Review of Cause-Related Marketing Literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 139, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, R.P.; Wilson, T. The impact of cause branding on consumer reactions to products: Does product/cause ‘fit’ really matter? J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Company advertising with a social dimension: The role of noneconomic criteria. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gürhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracejus, J.W.; Olsen, G.D. The role of brand/cause fit in the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, E.B.; Cáceres, R.C.; Pérez, R.C. Alliances between brands and social causes: The influence of company credibility on social responsibility image. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Eaton, J. Building brand image through event sponsorship: The role of image transfer. J. Advert. 1999, 28, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, S. The Effects of sponsor relevance on consumer reactions to internet sponsorships. J. Advert. 2003, 32, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Norman, A.T.; Miyazaki, A.D. Consumer response to retailer use of cause-related marketing: Is more fit better? J. Retail. 2007, 83, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.R.; Irmak, C.; Jayachandran, S. Choice of cause in cause-related marketing. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, B.E. Corporate sponsorships of philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of sponsor brand? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, E.; Currás-Pérez, R.; Aldás-Manzano, J. Dual nature of cause-brand fit: Influence on corporate social responsibility consumer perception. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.J.; Becker-Olsen, K.L. Achieving marketing objectives through social sponsorships. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Sung, Y.; Lee, M. Consumer evaluations of social alliances: The effects of perceived fit between companies and non-profit organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, S.; Magnusson, P.; Stanley, S.M. Dimensions of fit between a brand and a social cause and their influence on attitudes. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A. Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. Human Motivation: Metaphors, Theories, and Research, 2nd revised ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Stefan, I.V.; Hoyer, W.D. Willingness to pay for cause-related marketing: The impact of donation amount and moderating effects. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.; Kwon, W.S.; Forsythe, S. Creating effective cause-related marketing campaigns: The role of cause-brand fit, campaign news source, and perceived motivations. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasuwa, G. Do the ends justify the means? How altruistic values moderate consumer responses to corporate social initiatives. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3714–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosmanoglu, E.; Altinigne, N.; Isiksal, D.G. CSR motivation and customer extra-role behavior: Moderation of ethical corporate identity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4161–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Tsamakos, A.; Vrechopoulos, A.P.; Avramidis, P.K. Corporate social responsibility: Attributions, loyalty, and the mediating role of trust. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.; Kwon, W.S. A model of antecedents of consumers’ post brand attitude upon exposure to a cause–brand alliance. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2013, 18, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné-Alcañiz, E.; Currás-Pérez, R.; Sánchez-García, I. Brand credibility in cause-related marketing: The moderating role of consumer values. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2009, 18, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pirsch, J. The company-cause-customer fit decision in cause-related marketing. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 23, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, D.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Pauwels, P. The effect of strategic and tactical cause-related marketing on consumers’ brand loyalty. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Rapert, M.I.; Newman, C.L. Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. Available online: http://sharedvalue.org/resources/strategy-society-link-between-competitive-advantage-and-corporate-social-responsibility (accessed on 10 May 2015). [PubMed]

- Irmak, C.; Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Consumer reactions to business-nonprofit alliances: Who benefits and when? Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, J.A.G.; Niedrich, R.W.; Grau, S.L. Cause-relating marketing: The effects of purchase quantity and firm donation amount on consumer inferences and participation intentions. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Lynch, R.; Melewar, T.C.; Jin, Z. The moderating influences on the relationship of corporate reputation with its antecedents and consequences: A meta-analytic review. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Spector, P.E. The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2003, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 555–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osbaldiston, R.; Schott, J.P. Environmental sustainability and behavioral science: Meta-analysis of proenvironmental behavior experiments. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 257–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Wilson, D.B. Practical Meta-Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Card, N.A. Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, T.D. Wheat from chaff: Meta-analysis as quantitative literature review. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Basil, D.Z.; Herr, P.M. Attitudinal balance and cause-related marketing: An empirical application of balance theory. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V. Fitting categorical models to effect sizes from a series of experiments. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1982, 7, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Hill, R.P. The impact of sponsor fit on brand equity the case of nonprofit service providers. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, A.B.; Grau, L. Explicit donations and inferred endorsements. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; Montaner, T. La influencia de las acciones de marketing con causa en la actitud hacia la marca. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2012, 15, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéron, E.; Kohlbacher, F.; Kusuma, K. The effects of brand-cause fit and campaign duration on consumer perception of cause-related marketing in Japan. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Guha, A.; Biswas, A.; Krishnan, B. How product–cause fit and donation quantifier interact in cause-related marketing (CRM) settings: Evidence of the cue congruency effect. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. Charitable programs and the retailer: Do they mix? J. Retail. 2000, 76, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Morrison, P. An examination of the formation of consumer CSR association: When corporate social responsible initiatives are effective. Asia Pac. Adv. Consum. Res. 2009, 8, 68–75. Available online: http://www.acrwebsite.org/search/view-conference-proceedings.aspx?Id=14762 (accessed on 12 May 2015).

- Ham, S.; Han, H. Role of perceived fit with hotels’ green practices in the formation of customer loyalty: Impact of environmental concerns. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Choi, J.; Kim, H.; Davis, J.A.; Lee, K.Y. The effectiveness of image congruence and the moderating effects of sponsor motive and cheering event fit in sponsorship. Int. J. Advert. 2013, 32, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A.H.; Das, N. Thinking about fit and donation format in cause marketing: The effects of need for cognition. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2013, 21, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S. A reputational approach examining publics’ attributions on corporate social responsibility motives. Asian J. Commun. 2011, 21, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Kim, S. Product Donations in Cause-Related Marketing Campaigns. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2016, 20, 66–78. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/openview/e58dd159d88724e93a47dbcd007b6753/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=38744 (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Huber, I.V.; Hoyer, W.D. When will price increases associated with company donations to charity be perceived as fair? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 44, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, A.; Rice, D.H. The impact of perceptual congruence on the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. The relevance of fit in a cause–brand alliance when consumers evaluate corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. Selecting the right cause partners for the right reasons: The role of importance and fit in cause-brand alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ferreira, M. A role of team and organizational identification in the success of cause-related sport marketing. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Heo, K. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N.J.; Choi, S.M.; Trimble, C.S.; Li, H. Congruence effects in sponsorship: The mediating role of sponsor credibility and consumer attributions of sponsor motive. J. Advert. 2004, 33, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Yang, S.U.; Lee, J. Strategic partnerships with nonprofits in corporate social responsibility (CSR): The mediating role of perceived altruism and organizational identification. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3213–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, S.; Wymer, W. The effect of fit and dominance in cause marketing communications. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, S.; Wymer, W. Cause marketing communications: Consumer inference on attitudes towards brand and cause. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1333–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, S.Y.; Han, J.K.; Lee, S.H. Communication strategies for enhancing perceived fit in the CSR sponsorship context. Int. J. Advert. 2012, 31, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberg, K.; Pope, N. An examination of cause-related marketing in the context of brand attitude, purchase intention, perceived fit and personal values. In Proceedings of the ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Social, Not-for-Profit and Political Marketing, Fremantle, Australia, 5–7 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.F.; Lai, C.S.; Kao, Y.T. The determinants of attribution for corporate social responsibility. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

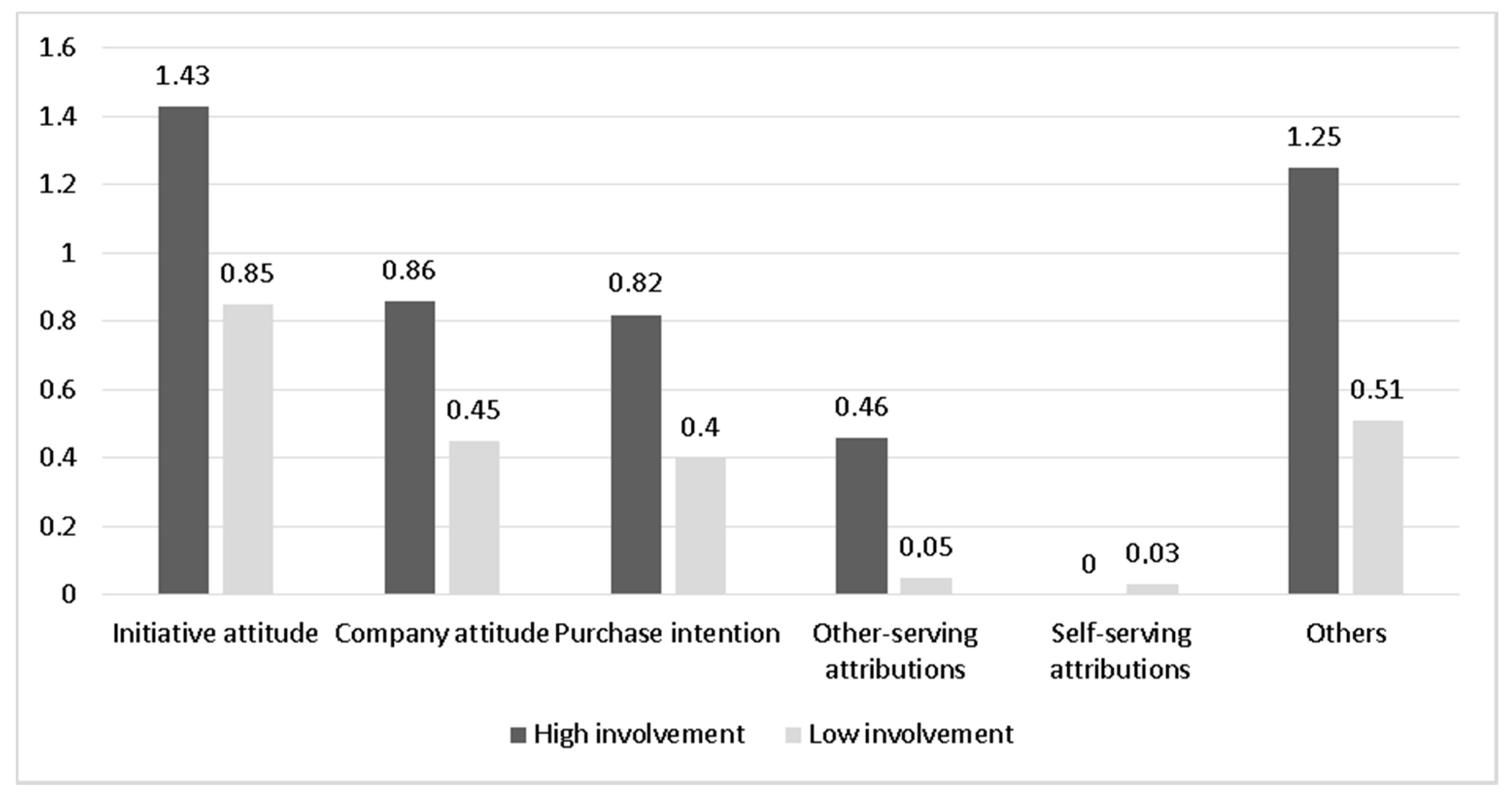

| CSR Outcome | C In. | K | N | Z | CI− | CI+ | QT | QB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiative attitude | |||||||||

| Total | 20 | 4816 | 0.93 | 30.06 *** | 0.87 | 0.99 | 344.42 | ||

| High | 6 | 718 | 1.43 | 16.70 *** | 1.26 | 1.59 | 59.09 | 38.98 *** | |

| Low | 14 | 4098 | 0.85 | 25.76 *** | 0.79 | 0.92 | 246.34 | ||

| Company attitude | |||||||||

| Total | 31 | 5387 | 0.53 | 18.85 *** | 0.48 | 0.59 | 352.66 | ||

| High | 7 | 1060 | 0.86 | 13.31 *** | 0.73 | 0.99 | 28.14 | 32.03 *** | |

| Low | 24 | 4327 | 0.45 | 14.49 *** | 0.39 | 0.52 | 292.49 | ||

| Purchase intention | |||||||||

| Total | 27 | 4582 | 0.52 | 17.13 *** | 0.46 | 0.58 | 163.53 | ||

| High | 8 | 1346 | 0.82 | 14.30 *** | 0.71 | 0.93 | 60.76 | 38.31 *** | |

| Low | 19 | 3236 | 0.40 | 11.28 *** | 0.33 | 0.47 | 64.45 | ||

| Other-serving attributions | |||||||||

| Total | 23 | 5326 | 0.25 | 8.83 *** | 0.19 | 0.30 | 348.46 | ||

| High | 12 | 2610 | 0.46 | 11.34 *** | 0.38 | 0.54 | 165.92 | 52.40 *** | |

| Low | 11 | 2716 | 0.05 | 1.33 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 130.14 | ||

| Self-serving attributions | |||||||||

| Total | 8 | 1371 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 17.18 | ||

| High | 2 | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.39 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| Low | 6 | 1271 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.11 | 17.17 | ||

| Others | |||||||||

| Total | 8 | 1377 | 0.69 | 12.10 *** | 0.57 | 0.80 | 153.00 | ||

| High | 3 | 391 | 1.25 | 10.75 *** | 1.03 | 1.48 | 78.38 | 31.29 *** | |

| Low | 5 | 986 | 0.51 | 7.73 *** | 0.38 | 0.63 | 43,32 | ||

| Positive Reputation | Negative Reputation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR Outcomes | C In. | K | N | K | N | QB pos vs. neg | ||

| Initiative attitude | ||||||||

| High | 1.56 | 5 | 663 | 0.17 | 1 | 55 | 23.99 *** | |

| Low | 0.85 | 14 | 4098 | n.a. | ||||

| QB low vs. high | 54.98 *** | n.a. | ||||||

| Company attitude | ||||||||

| High | 0.86 | 7 | 1060 | n.a. | ||||

| Low | 0.57 | 20 | 3907 | −0.69 | 4 | 420 | 132.13 *** | |

| QB low vs. high | 16.33 *** | n.a. | ||||||

| Purchase intention | ||||||||

| High | 0.82 | 8 | 1346 | n.a. | ||||

| Low | 0.41 | 18 | 3152 | −0.02 | 1 | 84 | 3.73 * | |

| QB low vs. high | 35.96 *** | n.a. | ||||||

| Other-serving attributions | ||||||||

| High | 0.47 | 11 | 2550 | 0.07 | 1 | 60 | 2.27 | |

| Low | 0.19 | 7 | 2388 | −1.09 | 4 | 328 | 111.12 *** | |

| QB low vs. high | 23.08 *** | 16.85 *** | ||||||

| Self-serving attributions | ||||||||

| High | 0.00 | 2 | 100 | n.a. | ||||

| Low | 0.17 | 3 | 358 | 0.02 | 2 | 100 | 0.01 | |

| QB low vs. high | 0.00 | n.a. | ||||||

| Others | ||||||||

| High | 1.25 | 3 | 391 | n.a. | ||||

| Low | 0.51 | 5 | 986 | n.a. | ||||

| QB low vs. high | 31.29 *** | n.a. | ||||||

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zasuwa, G. The Role of Company-Cause Fit and Company Involvement in Consumer Responses to CSR Initiatives: A Meta-Analytic Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9061016

Zasuwa G. The Role of Company-Cause Fit and Company Involvement in Consumer Responses to CSR Initiatives: A Meta-Analytic Review. Sustainability. 2017; 9(6):1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9061016

Chicago/Turabian StyleZasuwa, Grzegorz. 2017. "The Role of Company-Cause Fit and Company Involvement in Consumer Responses to CSR Initiatives: A Meta-Analytic Review" Sustainability 9, no. 6: 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9061016

APA StyleZasuwa, G. (2017). The Role of Company-Cause Fit and Company Involvement in Consumer Responses to CSR Initiatives: A Meta-Analytic Review. Sustainability, 9(6), 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9061016