Modes of Governing and Policy of Local and Regional Governments Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives; Exploring the Cases of the Dutch Regions of Overijssel and Fryslân

Abstract

:1. Introduction

In what ways do local and regional governments in the Dutch regions of Overijssel and Fryslân innovate in governing to respond to the emergence of LLCEIs?

2. Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Background

2.1. Conceptualizing Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives

2.2. The Role of LLCEIs in Governing Low-Carbon Energy Transitions

2.3. The Role of Government in Harnessing the Potential of LLCEIs

2.4. Enabling and Authoritative Modes of Governing

2.5. The Need for Experimental Meta-Governance

2.6. The Role of Institutional Adaptation

2.7. Policy Innovation

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Units of Analysis

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Limitations

4. Results

4.1. Provincial Governments and Municipalities in the Netherlands

4.2. The Case of Overijssel

4.2.1. The Provincial Government

4.2.2. Municipalities

4.3. The Case of Fryslân

4.3.1. The Provincial Government

4.3.2. Municipalities

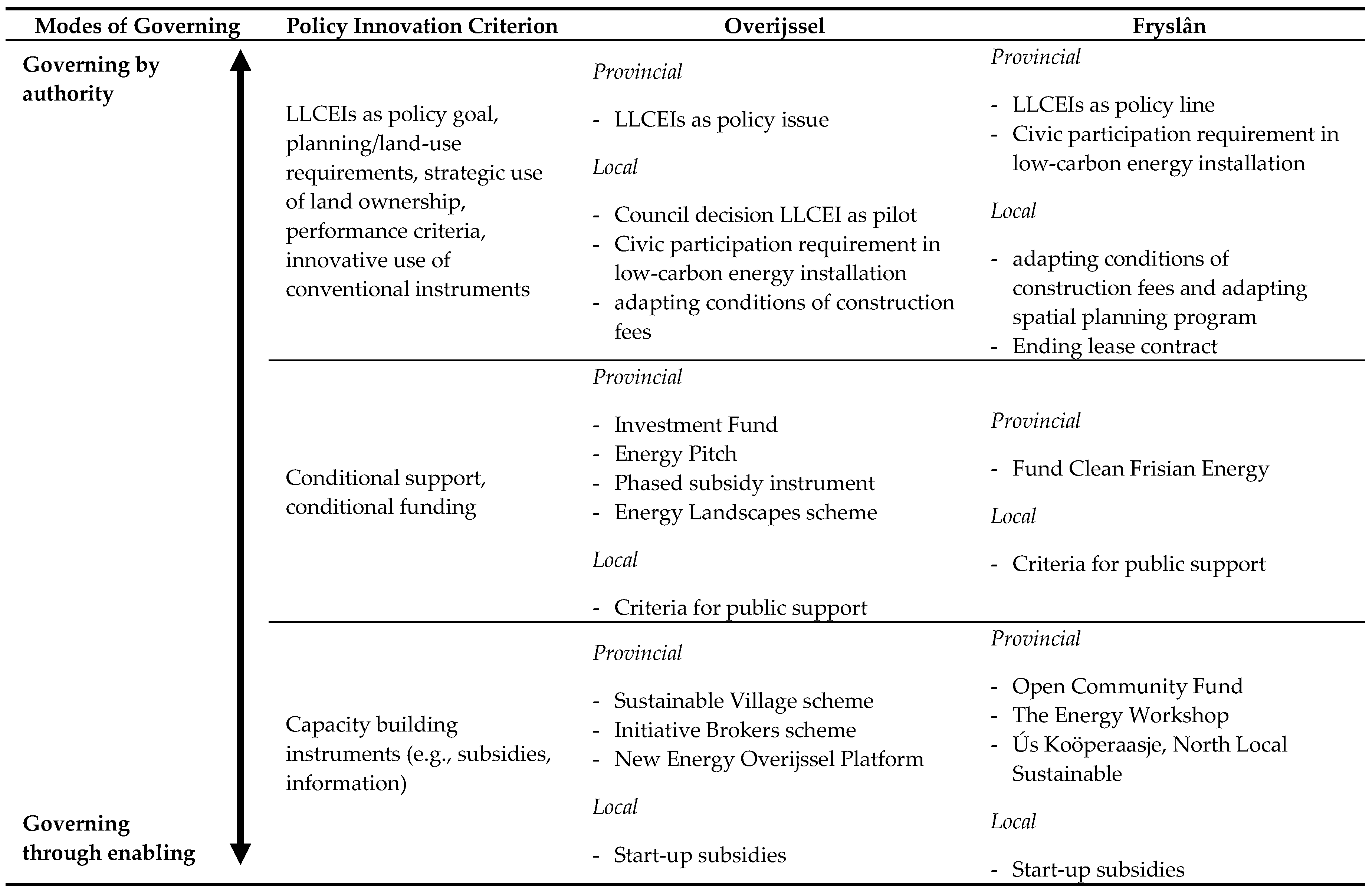

4.4. Results of the Comparative Analysis

4.4.1. Institutional Adaptation

4.4.2. Policy Innovation

5. Discussion

5.1. Innovations in Governing

5.2. Innovating within the Confines of Existing Structures

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLCEIs | Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives |

| NLD | Noordelijk Lokaal Duurzaam |

| FSFE | Fûns Skjinne Fryske Enerzjy |

| ECW | Energie Coöperatie Westeinde |

| WEN | Wijnjewoude Energie Neutraal |

| ECHT | Energie Coöperatie Hof van Twente |

| EK | EnergieKûbaard |

| EKE | Enerzjy Koöperaasje Easterwierrum |

| GEKE | Griene Enerzjy Koöperaasje Easterein |

| WEK | Wommelser Enerzjy Koöperaasje |

| CRL | Crisis and Recovery Law |

References

- Agterbosch, S. Empowering Wind Power; on Social and Institutional Conditions Affecting the Performance of Entrepreneurs in the Wind Power Supply Market in the Netherlands; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenke, A.M. Lokale Energie Monitor 2015; Hier Opgewekt: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oteman, M.; Wiering, M.; Helderman, J.-K. The institutional space of community initiatives for low-carbon energy: A comparative case study of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boon, F.P.; Dieperink, C. Local civil society based renewable energy organisations in the Netherlands: Exploring the factors that stimulate their emergence and development. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Who is in Charge here? Governance for Sustainable Development in a Complex World*. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chmutina, K.; Goodier, C.I. Alternative future energy pathways: Assessment of the potential of innovative decentralised energy systems in the UK. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mey, F.; Diesendorf, M.; MacGill, I. Can local government play a greater role for community renewable energy? A case study from Australia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.; Mayne, R.; Parag, Y.; Bergman, N. Scaling up local carbon action: The role of partnerships, networks and policy. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, S.; Shaw, A.; Dale, A.; Robinson, J. Triggering transformative change: A development path approach to climate change response in communities. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, J. Community-based energy policy: A practical approach to carbon reduction. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2007, 50, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B.G. Beyond Kyoto: Climate Change Policy in Multilevel Governance Systems. Governance 2007, 20, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufen, J.A.; Koppenjan, J.F. Local low-carbon energy cooperatives: Revolution in disguise? Energy Sustain. Soc. 2015, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wade, J.; Eyre, N.; Parag, Y.; Hamilton, J. Local energy governance: Communities and energy efficiency policy. In Proceedings of the ECEEE 2013 Summer Study on Energy Efficiency, Stockholm, Sweden, 3–8 June 2013.

- Hoppe, T.; Graf, A.; Warbroek, B.; Lammers, I.; Lepping, I. Local Governments Supporting Local Energy Initiatives: Lessons from the Best Practices of Saerbeck (Germany) and Lochem (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2015, 7, 1900–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.; Denters, B.; Oude vrielink, M.; Klok, P.-J. Citizens’ Initiatives: How Local Governments Fill their Facilitative Role. Local Gov. Stud. 2012, 38, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schoor, T.; Scholtens, B. Power to the people: Local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. Low-Carbon Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugetta, Y.; Jackson, T.; van der Horst, D. Carbon reduction at community scale. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7541–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomberg, E.; McEwen, N. Mobilizing community energy. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swyngedouw, E. Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownill, S.; Carpenter, J. Governance and ‘Integrated’ Planning: The Case of Sustainable Communities in the Thames Gateway, England. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Sullivan, H. How low can you go? Rationales and challenges for neighbourhood governance. Public Adm. 2008, 86, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Head, B.W. Community Engagement: Participation on Whose Terms? Aust. J. Political Sci. 2007, 42, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Hess, M. Community in Public Policy: Fad or Foundation? Aust. J. Public Adm. 2001, 60, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, G.C. Escaping carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D. Innovations in climate policy: The politics of invention, diffusion, and evaluation. Environ. Politics 2014, 23, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D. Policy innovation in a changing climate: Sources, patterns and effects. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broto, V.C.; Bulkeley, H. Maintaining climate change experiments: Urban political ecology and the everyday reconfiguration of urban infrastructure. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1934–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bulkeley, H.; Castán Broto, V. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castán Broto, V.; Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D. Innovations in climate policy: Conclusions and new directions. Environ. Politics 2014, 23, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genschel, P. The Dynamics of Inertia: Institutional Persistence and Change in Telecommunications and Health Care. Governance 1997, 10, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzara, G.F. Self-destructive processes in institution building and some modest countervailing mechanisms. Eur. J. Political Res. 1998, 33, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, K. How Institutions Evolve; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Streeck, W.; Thelen, K. Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Kern, K. Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, B.; Boelens, L. Self-organization in urban development: Towards a new perspective on spatial planning. Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederhand, J.; Bekkers, V.; Voorberg, W. Self-Organization and the Role of Government: How and why does self-organization evolve in the shadow of hierarchy? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, J.; van Meerkerk, I.; Koppenjan, J. The challenge of innovating politics in community self-organization: The case of Broekpolder. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 9037, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerkerk, I.; Boonstra, B.; Edelenbos, J. Self-Organization in Urban Regeneration: A Two-Case Comparative Research. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 21, 1630–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, G.; Cass, N. Carbon reduction, “the public” and low-carbon energy: Engaging with socio-technical configurations. Area 2007, 39, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Wiersma, B. Opening up the “local” to analysis: Exploring the spatiality of UK urban decentralised energy initiatives. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 1099–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.R. Spaces of dependence, spaces of engagement and the politics of scale, or: Looking for local politics. Political Geogr. 1998, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. The role for “community” in carbon governance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Kunze, C. Transcending community energy: Collective and politically motivated projects in renewable energy (CPE) across Europe. People Place Policy J. Compil. 2014, 8, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arentsen, M.; Bellekom, S. Power to the people: Local energy initiatives as seedbeds of innovation? Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vleuten, E.; Raven, R. Lock-in and change: Distributed generation in Denmark in a long-term perspective. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 3739–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.E.; Wenger, H.J.; Farmer, B.K. An alternative to electric utility investments capacity Brian K Farmer in system. Energy Policy 1996, 24, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeppel, G. Distributed Generation—Literature Review and Outline of the Swiss Situation; Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH): Zürich, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pepermans, G.; Driesen, J.; Haeseldonckx, D.; Belmans, R.; D’haeseleer, W. Distributed generation: Definition, benefits and issues. Energy Policy 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.M.; High-Pippert, A. From private lives to collective action: Recruitment and participation incentives for a community energy program. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7567–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E. “Let’s do it ourselves” Individual motivations for investing in renewables at community level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.C.; Simmons, E.A.; Convery, I.; Weatherall, A. Public perceptions of opportunities for community-based renewable energy projects. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4217–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Park, J.J.; Smith, A. A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agterbosch, S.; Meertens, R.M.; Vermeulen, W.J.V. The relative importance of social and institutional conditions in the planning of wind power projects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, C. Community perspectives of wind energy in Australia: The application of a justice and community fairness framework to increase social acceptance. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2727–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Planning of renewables schemes: Deliberative and fair decision-making on landscape issues instead of reproachful accusations of non-cooperation. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2692–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toke, D.; Breukers, S.; Wolsink, M. Wind power deployment outcomes: How can we account for the differences? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 1129–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, R.; Bristow, G.; Munday, M. Acceptance, acceptability and environmental justice: The role of community benefits in wind energy development. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musall, F.D.; Kuik, O. Local acceptance of renewable energy—A case study from southeast Germany. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3252–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.; Onkila, T.; Kuittinen, V. Realizing the social acceptance of community renewable energy: A process-outcome analysis of stakeholder influence. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R.; McFadyen, M. Does community ownership affect public attitudes to wind energy? A case study from south-west Scotland. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Co-provision in sustainable energy systems: The case of micro-generation. Energy Policy 2004, 32, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, R.; Watson, J. Strategies for the deployment of micro-generation: Implications for social acceptance. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2770–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E.; Petersen, A.C. Exploring the transition potential of renewable energy communities. Futures 2015, 66, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoor, T.; van der Lente, H.; van Scholtens, B.; Peine, A. Challenging obduracy: How local communities transform the energy system. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitlin, D. With and beyond the state—Co-production as a route to political influence, power and transformation for grassroots organizations. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geelen, D.; Reinders, A.; Keyson, D. Empowering the end-user in smart grids: Recommendations for the design of products and services. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxon, T.J. Transition pathways for a UK low carbon electricity future. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.; Hall, S. Community energy and equity: The distributional implications of a transition to a decentralised electricity system. People Place Policy Online 2014, 8, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolden, C. Governing community energy—Feed-in tariffs and the development of community wind energy schemes in the United Kingdom and Germany. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T.; Gotchev, B.; Holstenkamp, L. What drives the development of community energy in Europe? The case of wind power cooperatives. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, N.; Eyre, N. What role for microgeneration in a shift to a low carbon domestic energy sector in the UK? Energy Effic. 2011, 4, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Osti, G. Does civil society matter? Challenges and strategies of grassroots initiatives in Italy’s energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, G.C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Hinderer, N. Situative governance and energy transitions in a spatial context: Case studies from Germany. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, N.; Wiek, A. Success factors and strategies for sustainability transitions of small-scale communities—Evidence from a cross-case analysis. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, N.; Hawkes, A.; Brett, D.J.; Baker, P.; Barton, J.P.; Blanchard, R.E.; Brandon, N.P.; Infield, D.; Jardine, C.; Kelly, N.; et al. UK microgeneration. Part I: Policy and behavioural aspects. Proc. ICE Energy 2009, 162, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A.; Berkhout, F. The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaï, A.; Labussière, O.; Debourdeau, A.; Régnier, Y.; Cointe, B.; Dobigny, L. French policy localism: Surfing on “Positive Energie Territories” (Tepos). Energy Policy 2015, 78, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. The research agenda on social acceptance of distributed generation in smart grids: Renewable as common pool resources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyterlinde, M.A.; Sambeek, E.J.W.; Cross, E.D.; JörX, W.; Löffler, P.; Morthorst, P.E.; Jørgensen, B.H. Decentralised Generation: Development of EU Policy; Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN): Petten, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang, G.; Hielscher, S.; Hargreaves, T.; Martiskainen, M.; Smith, A. A grassroots sustainable energy niche? Reflections on community energy in the UK. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markantoni, M. Low Carbon Governance: Mobilizing Community Energy through Top-Down Support? Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Fudge, S.; Sinclair, P. Mobilising community action towards a low-carbon future: Opportunities and challenges for local government in the UK. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7596–7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.; Healey, P. A Sociological Institutionalist Approach to the Study of Innovation in Governance Capacity. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2055–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.; Joas, M.; Sundback, S.; Theobald, K. Governing local sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2006, 49, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.V.; Wang, X. Sustainable Development Governance: Citizen Participation and Support Networks in Local Sustainability Initiatives. Public Works Manag. Policy 2012, 17, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M. The Energetic Society: In Search of a Governance Philosophy for a Clean Economy; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, J.; Peters, G.B. Governance, Politics and the State; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, K.H. Governance as a Path to Government. West Eur. Politics 2008, 31, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.J.; Lynn, L.E. Is hierarchical governance in decline? Evidence from empirical research. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Hindmoor, A.; Mols, F. Persuasion as governance: A state-centric relational perspective. Public Adm. 2010, 88, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. Capitalism and its future: Remarks on regulation, government and governance. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 1997, 4, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. Governance and Meta-governance in the Face of Complexity: On the Roles of Requisite Variety, Reflexive Observation, and Romantic Irony in Participatory Governance. In Participatory Governance in Multi-Level Context; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, P. Community governance and democracy. Policy Politics 2005, 33, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Making governance networks effective and democratic through metagovernance. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, E.; Torfing, J. Metagoverning Collaborative Innovation in Governance Networks. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Healey, P. “My Voice: My Place”: Tracking Transformations in Urban Governance. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1979–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M. Policy without Polity? Policy Analysis and the Institutional Void. Policy Sci. 2003, 36, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski, I.; Carmin, J. Something borrowed, everything new: Innovation and institutionalization in urban climate governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; van den Berg, M.M.; Coenen, F.H. Reflections on the uptake of climate change policies by local governments: Facing the challenges of mitigation and adaptation. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, R.; Hamilton, J.; Lucas, K. Roles and Change Strategies of Low Carbon Communities; Evaluating Low Carbon Communities (EVALOC): Oxford, UK, 2013; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, E. Metagovernance: The Changing Role of Politicians in Processes of Democratic Governance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 36, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, P.; Dowling, R.; Bulkeley, H. Repositioning urban governments? Energy efficiency and Australia’s changing climate and energy governance regimes. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2717–2734. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Dowling, R.; McGuirk, P.; Bulkeley, H. Governing Carbon in the Australian City: Local Government Responses; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H. Reconfiguring environmental governance: Towards a politics of scales and networks. Political Geogr. 2005, 24, 875–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jordan, A.; Wurzel, R.K.W.; Zito, A.R. Still the century of “new” environmental policy instruments? Exploring patterns of innovation and continuity. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham, N. Enforcing Environmental Regulation. J. Environ. Law 2011, 23, 169–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Schroeder, H. Governing Climate Change Post-2012: The Role of Global Cities—London. 2008. Available online: http://www.tyndall.ac.uk/content/governing-climate-change-post-2012-role-global-cities-london (accessed on 22 December 2016).

- Baker, S.; Mehmood, A. Social innovation and the governance of sustainable places. Local Environ. 2013, 20, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F.W. Games real actors could play: Positive and negative coordination in embedded negotations. J. Theor. Politics 1994, 6, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity 2009; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M. Community Participation in the Real World: Opportunities and Pitfalls in New Governance Spaces. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Urban Regeneration’s Poisoned Chalice: Is There an Impasse in (Community) Participation-based Policy? Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.; Wright, E.O. Deepening democracy: Innovations in empowered participatory governance. Politics Soc. 2001, 29, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E.; Ghosh, A. Innovations for enabling urban climate governance: Evidence from Mumbai. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 926–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, J. Experimental governance for low-carbon buildings and cities: Value and limits of local action networks. Cities 2016, 53, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, P.; Dowling, R.; Brennan, C.; Bulkeley, H. Urban Carbon Governance Experiments: The Role of Australian Local Governments. Geogr. Res. 2015, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gordon, D.J. Between local innovation and global impact: Cities, networks, and the governance of climate change. Can. Foreign Policy J. 2013, 19, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Wilson, D. Social Capital and Local Governance: Exploring the Institutional Design Variable. Political Stud. 2001, 49, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Wilson, D.J. Balancing revisability and robustness? A new institutionalist perspective on local government modernization. Public Adm. 2003, 81, 275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, M. Partnership and the Limits to Local Governance in England: Institutionalist Analysis and Neoliberalism. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, M.A. From the Bottom up Local and Subnational Climate Change Politics. J. Environ. Dev. 2008, 17, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.D.; Ferreira, L.D.C. Opportunities and constraints for local and subnational climate change policy in urban areas: Insights from diverse contexts. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2011, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsill, M.M. Mitigating Climate Change in US Cities: Opportunities and obstacles. Local Environ. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2001, 6, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T.; Becker, S.; Naumann, M. Whose energy transition is it, anyway? Organisation and ownership of the Energiewende in villages, cities and regions. Local Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews-Speed, P. Applying institutional theory to the low-carbon energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M.; Kuzemko, C.; Mitchell, C.; Hoggett, R. Historical institutionalism and the politics of sustainable energy transitions: A research agenda. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave, T.J.; Van De Ven, A.H. A collective action model of institutional innovation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 864–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, L.M.; Elmore, R.F. Getting the Job Done: Alternative Policy Instruments. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1987, 9, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, I.; Heldeweg, M.A. Smart Design Rules for Smart Grids: Analysing Local Smart Grid Development through an Empirico-Legal Institutional Lens. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; McCaughie, K. Weathering the perfect storm? Austerity and institutional resilience in local government. Policy Politics 2013, 41, 533–549. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson, P. When Effect Becomes Cause: Policy Feedback and Political Change. World Politics 1993, 45, 595–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T.; Hielscher, S.; Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kivimaa, P. Government-affiliated intermediary organisations as actors in system-level transitions. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.; Barnes, J. Scaling up community activism: The role of intermediaries in collective approaches to community energy. People Place Policy Online 2014, 8, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J. Intermediaries as Innovating Actors in the Transition to a Sustainable Energy System. Cent. Eur. J. Public Policy 2010, 4, 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- Parag, Y.; Hamilton, J.; White, V.; Hogan, B. Network approach for local and community governance of energy: The case of Oxfordshire. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T. Intermediaries and the governance of sociotechnical networks in transition. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Wurzel, R.K.W.; Zito, A. The Rise of “New” Policy Instruments in Comparative Perspective: Has Governance Eclipsed Government? Political Stud. 2005, 53, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedby, N.; Quitzau, M.-B. Municipal Governance and Sustainability: The Role of Local Governments in Promoting Transitions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, E. The double-edged sword of grant funding: A study of community-led climate change initiatives in remote rural Scotland. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B. Participation or Co-Governance? Challenges for regional natural resource management. In Participation and Governance in Regional Development: Global Trends in an Australian Context; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2005; pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Province of Overijssel. Motie energie van de samenleving. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/sis/16301427653066.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Fryslân. Afhandeling Amendement Lokale en kleinschalige initiatieven duurzame energie. 2014. Available online: 05-Brief DS Afhandeling amendement lokale en kleinschalige initiatieven duurzame energie 20140703.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Gerring, J. Case Study Research. Principles and Practices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F. Creating an analytical framework for local sustainability performance: A Dutch Case Study. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressers, H.; de Bruijn, T. Conditions for the success of negotiated agreements: Partnerships for environmental improvement in the Netherlands. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, F.; Menkveld, M. The role of local authorities in a transition towards a climate-neutral society. In Global Warming; Social Innovation. The Challenge of a Climate-Neutral Society; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002; pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Straatman, E.; Hoppe, T.; Sanders, M.P.T. Bestuurlijke ondersteuning van lokale energie-initiatieven: Duurzaam dorp in Overijssel. ROmagazine, 2013; 31, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M.P.; Heldeweg, M.A.; Straatman, E.G.; Wempe, J.F. Energy policy by beauty contests: The legitimacy of interactive sustainability policies at regional levels of the regulatory state. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Province of Overijssel. Duurzaam Dorp Overijssel. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/thema’s/milieu/duurzaamheid/duurzaam-dorp/ (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Overijssel. Uitvoeringsprogramma Energiepact; PS/2011/206; 2011. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/sis/16301110238192.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Overijssel. Herijking programma Nieuwe Energie; PS/2014/442; 2014. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/sis/16301420533522.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Bressers, H.; Bruijn, T.D.; Lulofs, K. Environmental negotiated agreements in the Netherlands. Environ. Politics 2009, 18, 58–77. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Province of Overijssel. Participatiecode Overijssel; PS/2014/1080; 2014. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/sis/16301508541917.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Overijssel. Ontwikkelen Programma Nieuwe Energie 2016–2020; PS/2016/105; 2016. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/sis/16201607453548.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Overijssel. Subsidie voor Lokale Energie-Initiatieven. 2016. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/loket/subsidies/@Jg8/lokale-energie/ (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Overijssel. Energielandschappen Overijssel. 2014. Available online: http://www.overijssel.nl/loket/subsidies/@G8M/energielandschappen/ (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Hoppe, T.; van der Vegt, A.; Stegmaier, P. Presenting a Framework to Analyze Local Climate Policy and Action in Small and Medium-Sized Cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipal Council Raalte. Raadsbesluit grootschalige duurzame energiebronnen. Zaaknummer 3981. 2014. Available online: https://raalte.notubiz.nl/document/1155241/1/140206102140 (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Municipal Executive Raalte. Raadsvoorstel Grootschalige Duurzame Energiebronnen. Zaaknummer 3981; Municipal Executive Raalte: Dutch, The Netherlands, 2013. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, T.; Arentsen, M.J.; Sanders, M.P.T. Lokale Waarden voor lokale energiesystemen. Rooilijn 2015, 48, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Province of Fryslân. Fryslân Duurzaam—De kim voorbij: Een nieuwe koers voor een duurzame toekomst van Fryslân. 2009. Available online: http://www.fryslan.frl/2489/duurzame-energie/files/%5B95%5Dfryslan_duurzaam_definitieve_versie_vastgesteld_door_ps_090423.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Province of Fryslân. Fryslân geeft energie: Programmaplan Duurzame Energie; Province of Fryslân: Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 2009. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Province of Fryslân. Afhandeling motie over energiecoöperaties. 2012. Available online: http://www.fryslan.frl/3901/ingekomen-stukken-week-32,-33,-34,-35-2012/files/05.0%20gs%20-%20afhandeling%20motie%20energiecooperaties.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Friesland Provincial Council. Amendement ondersteuning lokale en kleinschalige initiatieven op Begroting 2013; Friesland Provincial Council: Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 2012. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Oskam, H.P. Rol gemeenten in lokale energiesector. Energie+ 2012, 6, 28–30. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Evaluatie wijkondernemingen wijk Achter de Hoven. 2015. Available online: http://leeuwarden.notubiz.nl/document/2873735/1 (accessed on 22 December 2016). (In Dutch)

- Lowndes, V.; Skelcher, C. The Dynamics of Multi-organizational Partnerships: An Analysis of Changing Modes of Governance. Public Adm. 1998, 76, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, A.; Hargreaves, T.; Hielscher, S.; Martiskainen, M.; Seyfang, G. Making the most of community energies: Three perspectives on grassroots innovation. Environ. Plan. A 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turnheim, B.; Berkhout, F.; Geels, F.; Hof, A.; McMeekin, A.; Nykvist, B.; van Vuuren, D. Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Blanchet, T.; Kunze, C. Social movements and urban energy policy: Assessing contexts, agency and outcomes of remunicipalisation processes in Hamburg and Berlin. Util. Policy 2016, 41, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, T. Struggle over energy transition in Berlin: How do grassroots initiatives affect local energy policy-making? Energy Policy 2014, 78, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, P.A.; Cowell, R.; Ellis, G.; Sherry-Brennan, F.; Toke, D. Promoting Community Renewable Energy in a Corporate Energy World. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolthuis, R.K.; Hooimeijer, F.; Bossink, B.; Mulder, G.; Brouwer, J. Institutional entrepreneurship in sustainable urban development: Dutch successes as inspiration for transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, E.; Shandas, V. Innovation and climate action planning: Perspectives from municipal plans. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M.; Parker, G.; Doak, J. Reshaping spaces of local governance? Community strategies and the modernisation of local government in England. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M.; Flint, J. Communities, places and institutional relations: Assessing the role of area-based community representation in local governance. Political Geogr. 2001, 20, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, S. Constructing Legitimacy in the New Community Governance. Urban Stud. 2010, 48, 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. Neighbourhood governance: Holy Grail or poisoned chalice? Local Econ. 2003, 18, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Transforming governance: Challenges of institutional adaptation and a new politics of space1. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Wurzel, R.K.W.; Zito, A.R. “New” Instruments of Environmental Governance: Patterns and Pathways of Change. Environ. Politics 2003, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F.; Loorbach, D. Outliers or frontrunners? Exploring the (self-) governance of community-owned sustainable energy in Scotland and the Netherlands. Renew. Energy Gov. Lect. Notes Energy 2013, 23, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F.; Bosman, R.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Akerboom, S.; Boontje, P.; Hoffman, J.; Wittmayer, J. The (Self-) Governance of Community Energy: Challenges & Prospects; The Dutch Research Institute For Transitions: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warbroek, B.; Hoppe, T. Modes of Governing and Policy of Local and Regional Governments Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives; Exploring the Cases of the Dutch Regions of Overijssel and Fryslân. Sustainability 2017, 9, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010075

Warbroek B, Hoppe T. Modes of Governing and Policy of Local and Regional Governments Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives; Exploring the Cases of the Dutch Regions of Overijssel and Fryslân. Sustainability. 2017; 9(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarbroek, Beau, and Thomas Hoppe. 2017. "Modes of Governing and Policy of Local and Regional Governments Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives; Exploring the Cases of the Dutch Regions of Overijssel and Fryslân" Sustainability 9, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010075