Tourism and Sustainability in the Evaluation of World Heritage Sites, 1980–2010

Abstract

:1. Introduction

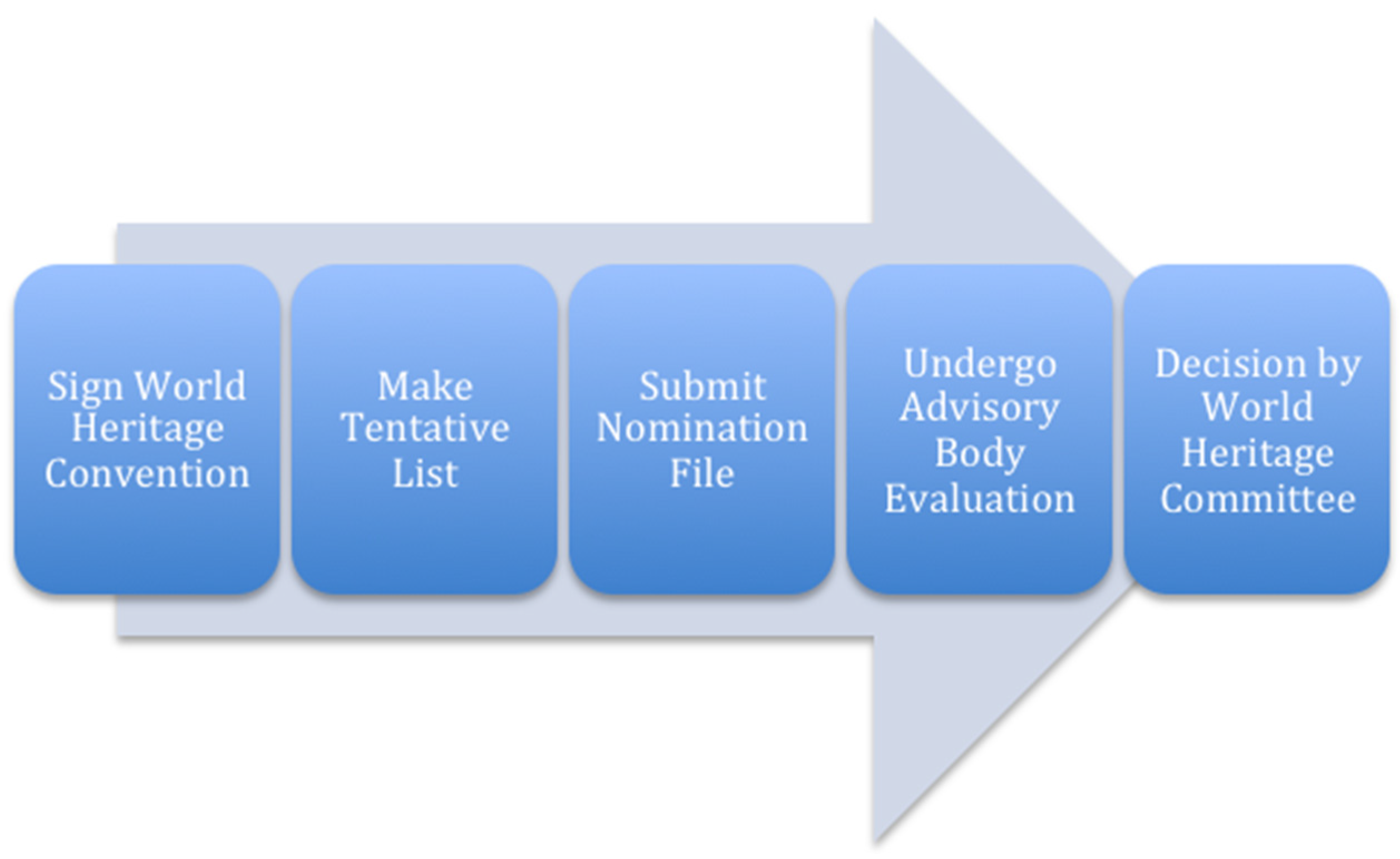

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials: Advisory Body Evaluations of Nominated Sites

2.2. Methods: Analysis of Advisory Body Evaluations

3. Results

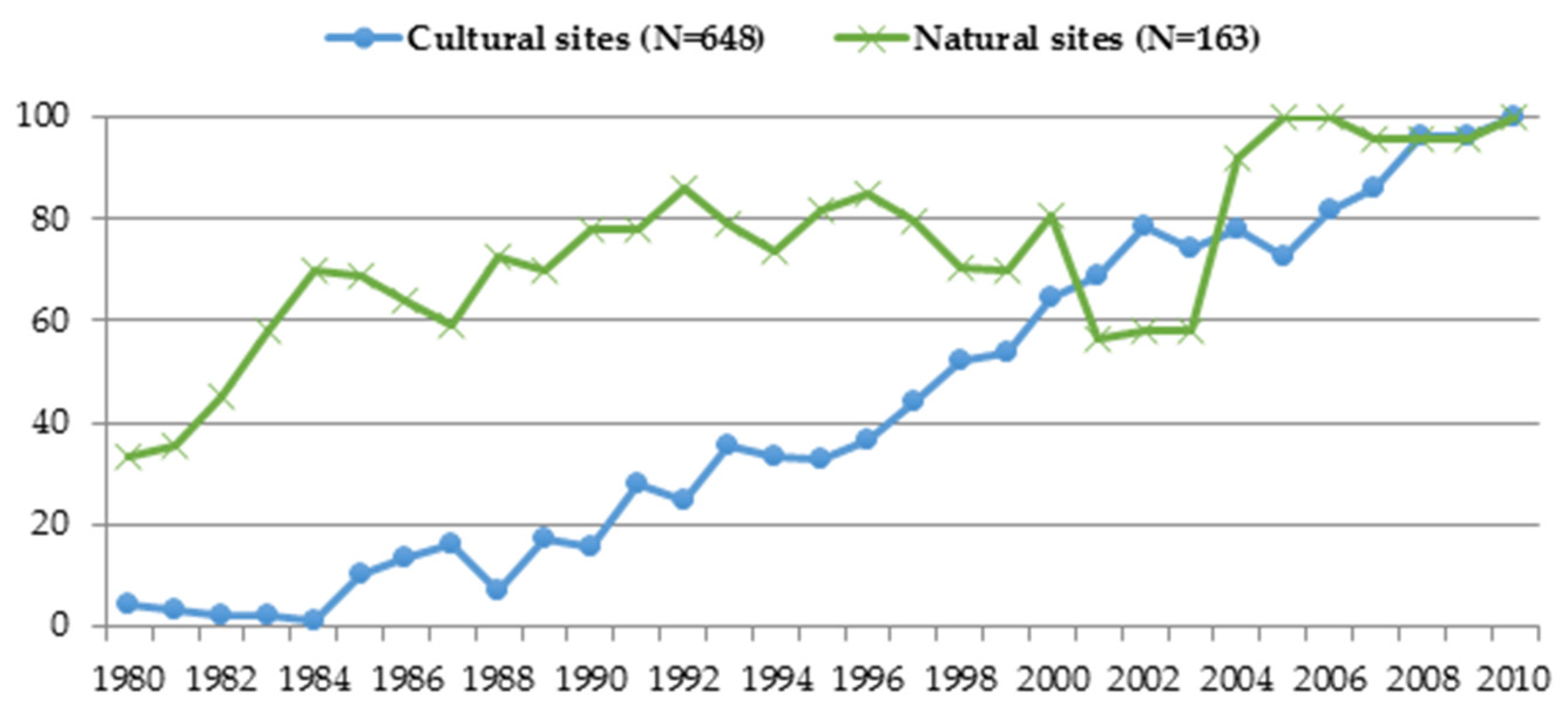

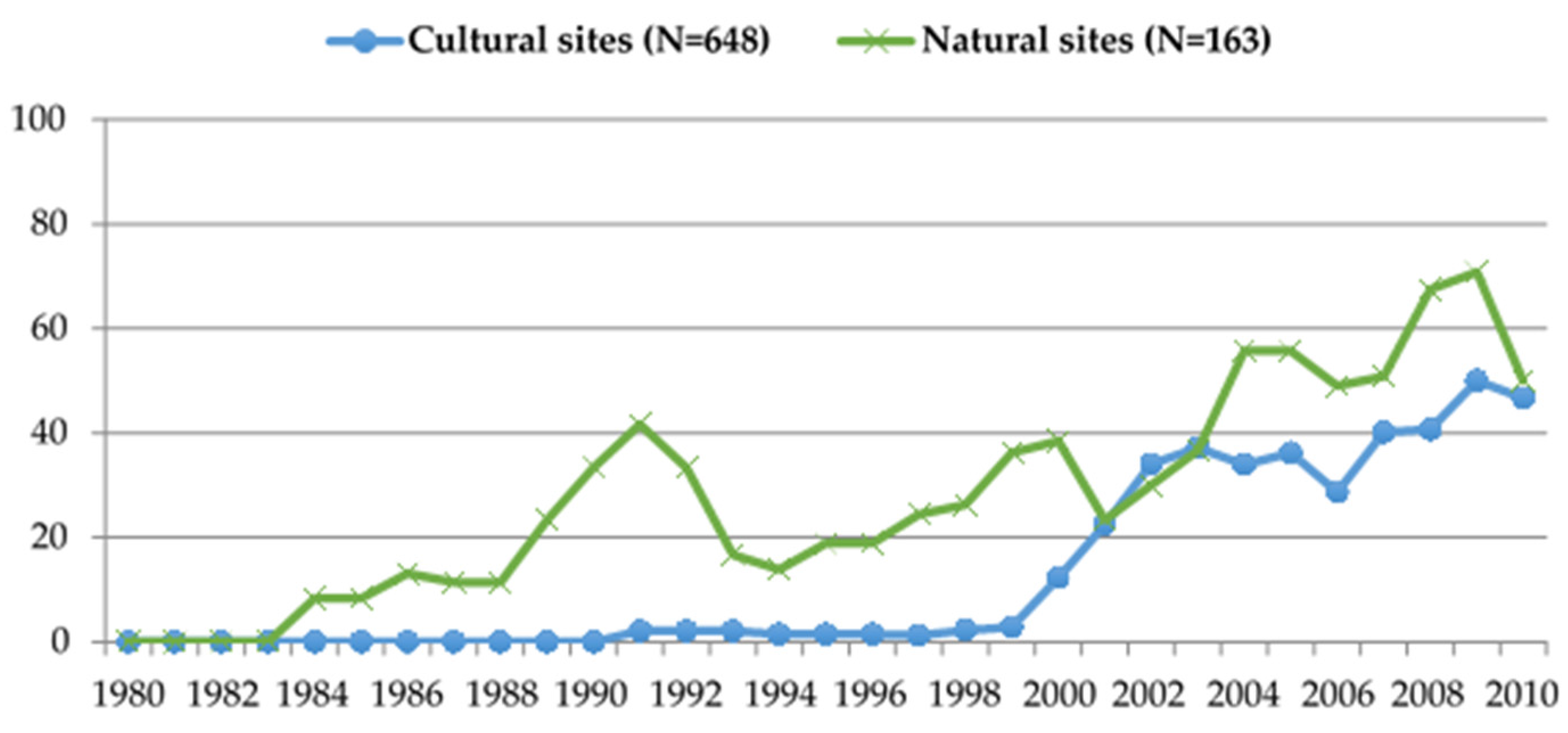

3.1. Word Count Results

3.2. Qualitative Coding Results

(a) maintains the current focus on low key, nature based tourism, based on the appreciation of natural values; (b) includes a carrying capacity assessment to guide tourism development …; (c) provides for direct and adequate financial contributions from tourism to … conservation and community development …; (d) closely involves the Yemeni General Tourism Development Authority and Tourism Promotion Board; (e) considers options for engaging in partnerships with environmentally sensitive private sector; and (f) addresses the lack of trained local tourist guides and literature[74] (p. 9).

4. Discussion

4.1. World Society Theory

4.2. Cultural Wealth of Nations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- Elliott, M.A.; Schmutz, V. World heritage: Constructing a universal cultural order. Poetics 2012, 40, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- States Parties Ratification Status. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/ (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- Schmutz, V.; Elliott, M.A. World heritage and the scientific consecration of “outstanding universal value”. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2016. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel-Bouchier, D. Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B. Some fundamental truths about tourism: Understanding tourism’s social and environmental impacts. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porananond, P.; King, V.T. Rethinking Asian Tourism: Culture, Encounters and Local Response; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Tomb raiding Angkor: A clash of cultures. Indone. Malay World 2003, 31, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S. UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism/ (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- World Heritage and Sustainable Development. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- Evans, G. World heritage and the World Bank: Culture and sustainable development? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2001, 26, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansing, P.; de Vries, P. Sustainable tourism: Ethical alternative or marketing ploy? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, J.W. World society, institutional theories, and the actor. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelj, N.; Wherry, F.F. The Cultural Wealth of Nations; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tunbridge, J.E.; Ashworth, G.J. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict; Wiley: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, I. The emergence of cultural heritage in Jordan: The itinerary of a colonial invention. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2009, 9, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleggi, M. National heritage and global tourism in Thailand. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Western hegemony in archaeological heritage management. Hist. Anthropol. 1991, 5, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleere, H. The World Heritage Convention in the third world. In Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites; McManamon, F., Hatton, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S. A review of the Global Strategy for a Balanced, Representative and Credible World Heritage List 1994–2004. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2005, 7, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel-Bouchier, D. Authenticity and identity: Theme-parking the Amanas. Int. Sociol. 2001, 16, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. A critical evaluation of the global accolade: The significance of World Heritage Site status for Maritime Greenwich. Int. J. Herit.Stud. 2002, 8, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Tsaur, J.; Yang, C. Does world heritage really induce more tourists? Evidence from Macau. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. Managing for sustainable tourism: A review of six cultural World Heritage Sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.M. The politics of heritage in Tana Toraja, Indonesia: Interplaying the local and the global. Indones. Malay World 2003, 31, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, R.; Morais, D.B.; Chick, G. Religion and identity in India’s heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 790–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.M. Art as Politics: Re-Crafting Identities, Tourism, and Power in Tana Toraja, Indonesia; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.C.; Milne, S.; Fallon, D.; Pohlmann, C. Urban heritage tourism: The global-local nexus. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W. The world polity and the authority of the nation-state. In Studies of the Modern World-System; Bergesen, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 109–137. [Google Scholar]

- Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M. World culture in the world polity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M. Constructing World Culture; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.J. Science, nature, and the globalization of the environment, 1870–1990. Soc. Forces 1997, 76, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.J.; Hironaka, A.; Schofer, E. The nation-state and the natural environment over the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandra, J.M.; Esparza, L.E.; London, B. Non-governmental organizations, democracy, and deforestation: A cross-national analysis. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Torres, A.; Palomeque, F.L. The growth and spread of the concept of sustainable tourism: The contribution of institutional initiatives to tourism policy. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, V. The production of cultural and natural wealth: An examination of world heritage sites. Poetics 2014, 44, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, M.A.; Bandelj, N.; Wherry, F.F. The political economy of cultural wealth. In The Cultural Wealth of Nations; Bandelj, N., Wherry, F.F., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, A. When cultural capitalization became global practice: The 1972 World Heritage Convention. In The Cultural Wealth of Nations; Bandelj, N., Wherry, F.F., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Regnault, M. Converting (or not) cultural wealth into tourism profits: Case studies of Reunion Island and Mayotte. In The Cultural Wealth of Nations; Bandelj, N., Wherry, F.F., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bair, J. Constructing scarcity, creating value: Marking the Mundo Maya. In The Cultural Wealth of Nations; Bandelj, N., Wherry, F.F., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, L.A. Impression management of stigmatized nations: The case of Croatia. In The Cultural Wealth of Nations; Bandelj, N., Wherry, F.F., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 114–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Field of Cultural Production; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tentative Lists. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/ (accessed on 26 January 2016).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 11 March 2013).

- Introducing ICOMOS. Available online: http://www.icomos.org/en/about-icomos/mission-and-vision/mission-and-vision (accessed on 6 March 2013).

- About IUCN. Available online: http://www.iucn.org/about/ (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- Meskell, L. States of conservation: Protection, politics, and pacting within UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee. Anthropol. Q. 2014, 87, 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention at 40: Challenging the economic and political order of international heritage conservation. Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heritage List. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/ (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Group of Monuments at Hampi; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Iguazu National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of the Medieval City of Rhodes; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Temple of Apollo Epicurius, Bassae; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Great Zimbabwe National Monument; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Chan Chan Archaeological Zone; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Kilimanjaro National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Paphos; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Royal Chitwan National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Ksar of Ait-Ben-Haddou; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Tipasa; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Historic Centre of Evora; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Comoe National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Gros Morne National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Bisotun; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of the Red Fort Complex; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Socotra Archipelago; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Tabriz Historic Bazaar; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of the Sacred Mijikenda Kaya Forests; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Fujian Tolou; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Old Town of Regensburg; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Genoa: Le Strade Nuove and the System of the Palazzi dei Rolli; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Evaluation of Jeju Volcanic Island and Lava Tubes; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Episcopal City of Albi; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Seventeenth-Century Canal Ring Area of Amsterdam; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gullino, P.; Becarro, G.L.; Larcher, F. Assessing and monitoring the sustainability in rural world heritage sites. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14186–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.A. The institutionalization of human rights and its discontents. Cult. Sociol. 2014, 8, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, F.; Boli, J. Trading diamonds responsibly: Institutional explanations for corporate social responsibility. Sociol. Forum 2011, 26, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.S.; Cho, M.; Drori, G.S. National transparency. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2014, 55, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. Toward a comparative sociology of valuation and evaluation. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2012, 38, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Cultural (ICOMOS) | Natural (IUCN) | Year Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980–1985 | 113 | 37 | 150 |

| 1986–1990 | 74 | 21 | 95 |

| 1991–1995 | 105 | 27 | 132 |

| 1996–2000 | 180 | 36 | 216 |

| 2001–2005 | 99 | 21 | 120 |

| 2006–2010 | 77 | 21 | 98 |

| Site total | 648 | 163 | 811 |

| Threat | No Threat/Unclear | Positive | Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL % (N = 44) | 25.0% (11) | 52.3% (23) | 22.7% (10) | 22.7% (10) |

| AFR % (N = 12) | 16.7% (2) | 41.7% (5) | 41.7% (5) | 25.0% (3) |

| APA % (N = 9) | 11.1% (1) | 88.9% (8) | 0.0% (0) | 22.2% (2) |

| ARB % (N = 3) | 0.0% (0) | 33.3% (1) | 66.7% (2) | 33.3% (1) |

| EUR % (N = 15) | 33.3% (5) | 53.3% (8) | 20.0% (3) | 20.0% (3) |

| LAC % (N = 5) | 60.0% (3) | 40.0% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 20.0% (1) |

| Threat | No Threat/Unclear | Positive | Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL % (N = 90) | 37.8% (34) | 63.3% (57) | 14.4% (13) | 57.8% (52) |

| AFR % (N = 9) | 44.4% (4) | 55.6% (5) | 0.0% (0) | 66.7% (6) |

| APA % (N = 31) | 54.8% (17) | 51.6% (16) | 9.7% (3) | 74.2% (23) |

| ARB % (N = 6) | 33.3% (2) | 66.7% (4) | 0.0% (0) | 83.3% (5) |

| EUR % (N = 33) | 24.4% (8) | 72.7% (24) | 21.2% (7) | 42.4% (14) |

| LAC % (N = 11) | 27.3% (3) | 72.7% (8) | 27.2% (3) | 36.4% (4) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmutz, V.; Elliott, M.A. Tourism and Sustainability in the Evaluation of World Heritage Sites, 1980–2010. Sustainability 2016, 8, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030261

Schmutz V, Elliott MA. Tourism and Sustainability in the Evaluation of World Heritage Sites, 1980–2010. Sustainability. 2016; 8(3):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030261

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmutz, Vaughn, and Michael A. Elliott. 2016. "Tourism and Sustainability in the Evaluation of World Heritage Sites, 1980–2010" Sustainability 8, no. 3: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030261