The Social Context of the Chinese Food System: An Ethnographic Study of the Beijing Seafood Market

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background of the Field Site and Methods

3. Conceptual Framework: Food Systems, Social Context and Chinese Consumption

4. Results

4.1. Changing Forms of Consumption and Trade in the Beijing Seafood Market

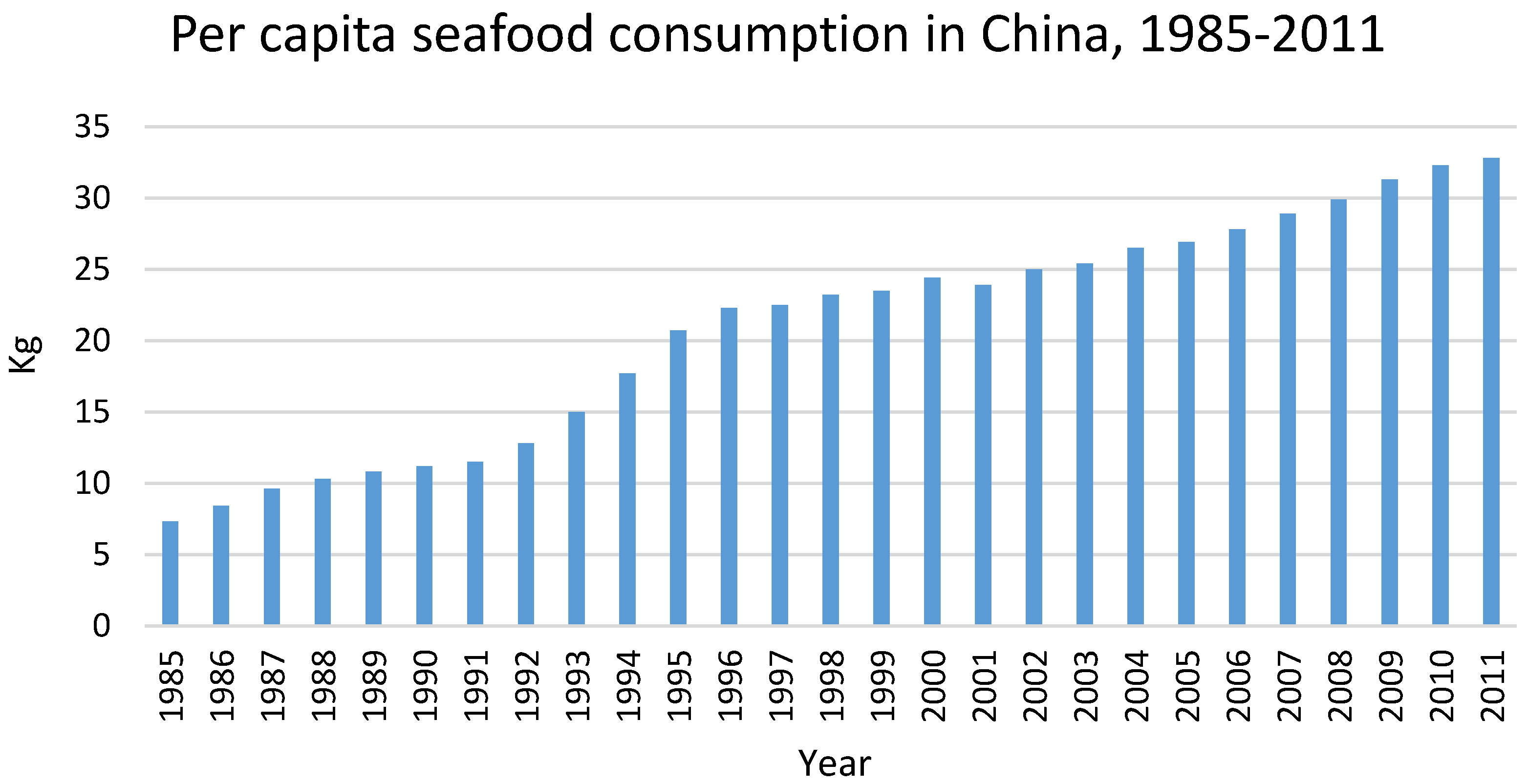

4.1.1. General Patterns of Seafood Consumption and Consumer Preferences

4.1.2. Logistics and Business Structures

4.2. Regulatory and Governance Environment

4.2.1. Government–Trader Relationship

4.2.2. Food Safety

4.2.3. Protected Species and Sustainability

4.2.4. Grey Trade

4.2.5. Anti-Corruption Campaign

“If you had come here for an interview in the past, we would have had no time for an interview… We used to sell 1000–2000 pieces per month (CNY 700–800,000), now just 1–2 pieces… For abalone in a month we could sell 70–80 jin a month. Now we cannot sell it at all for 1–2 months. Shark fin cannot sell, it is almost stagnant. The pressure is big. I have loans of approximately CNY5 million, interest of CNY 600,000 yuan a year. Plus CNY 250,000 rent for market, plus 4–5 workers, CNY 100,000 salary, food, housing rent, another 100,000 totaling CNY 1.2 million for a year. Let’s not speak of making money now. Isn’t the pressure huge?”

4.2.6. Social Institutions

5. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Z.; Tian, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Cao, L. Food consumption trends in China. Available online: http://www.agriculture.gov.au/ag-farm-food/food/publications/food-consumption-trends-in-china (accessed on 11 January 2016).

- Popkin, B. Synthesis and implications: China’s nutrition transition in the context of changes across other low- and middle-income countries. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, F.Y.; Du, S.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.G.; Du, W.W.; Popkin, B.M. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, T. Chinese drought, bread and the Arab Spring. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 34, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economy, E.; Levi, M. By All Means Necessary: How China’s Resource Quest Is Changing the World; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Fish to 2030: Prospects for Fisheries and Aquaculture; Agriculture and Environment Services Discussion Paper 3; World Bank Report number 83177-GLB; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fabinyi, M.; Liu, N. Seafood consumption in Beijing restaurants: Consumer perspectives and implications for sustainability. Conserv. Soc. 2014, 12, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, H.; Clarke, S. Chinese market responses to overexploitation of sharks and sea-cucumbers. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 184, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Naylor, R.; Henriksson, P.; Leadbitter, D.; Metian, M.; Troell, M.; Zhang, W. China’s aquaculture and the world’s wild fisheries. Science 2015, 347, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crona, B.I.; van Holt, T.; Petersson, M.; Daw, T.M.; Buchary, E. Using social–ecological syndromes to understand impacts of international seafood trade on small-scale fisheries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österblom, H.; Folke, C. Globalization, marine regime shifts and the Soviet Union. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2015, 370, 20130278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- French, P.; Crabbe, M. Fat China: How Expanding Waistlines Are Changing a Nation; Anthem Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Reardon, T.; Rozelle, S.; Timmer, P.; Wang, H. The Emergence of Supermarkets with Chinese Characteristics: Challenges and Opportunities for China’s Agricultural Development. Dev. Policy Rev. 2004, 22, 557–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, P.C.; Minten, B. Supermarket revolution in Asia and emerging development strategies to include small farmers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12332–12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villasante, S.; Rodríguez-González, D.; Antelo, M.; Rivero-Rodríguez, S.; de Santiago, J.A.; Macho, G. All fish for China? Ambio 2013, 42, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfray, H.C.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Nisbett, N.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Toulmin, C.; Whiteley, R. The future of the global food system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 2769–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B. Nutrition, agriculture and the global food system in low and middle income countries. Food Policy 2014, 47, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, J.G. Consumption. In Encyclopaedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology; Barnard, A., Spencer, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- Croll, E. China’s New Consumers: Social Development and Domestic Demand; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.Y.H.; Cheung, S.C.H. The Globalization of Chinese Food; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bestor, T.C. Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Turgo, N. ‘Laway lang ang kapital’ (Saliva as capital): Social embeddedness of market practices in brokerage houses in the Philippines. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 43, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.; Dicken, P.; Hess, M. Global production networks: Realizing the potential. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-Hart, N.; Stringer, C. Upgrading and exploitation in the fishing industry: Contributions of value chain analysis. Mar. Policy 2015, 63, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N. Geographies of production II: A global production network A–Z. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 36, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetham, D. The Legitimation of Power; Humanities Press International: Atlantic Highlands, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S. Legitimacy and disappointment in fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, P.E. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. A food systems approach to researching interactions between food security and global environmental change. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Ingram, J. Food Security Twists and Turns: Why Food Systems need Complex Governance. In Addressing Tipping Points for a Precarious Future; O’Riordan, T., Lenton, T., Eds.; British Academy Scholarship and Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, A.; Li, L.; Guo, S.; Bai, J.; Fedor, C.; Naylor, R.L. Feed and fish meal use in the production of carp and tilapia in China. Aquaculture 2013, 414–415, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org/ (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Rabobank. The Dragon’s Changing Appetite: How China’s Evolving Seafood Industry and Consumption Are Impacting Global Seafood Markets. Available online: http://transparentsea.co/images/c/c5/Rabobank_IN341_The_Dragons_Changing_Appetite_Nikolik_Chow_October2012.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2016).

- Campling, L. Assessing Alternative Markets: Pacific Islands Canned Tuna & Tuna Loins; Technical Report; Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency: Honiara, Solomon Islands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.N. The Food of China; Yale University Press: London, UK; New Haven, CT, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fabinyi, M. Producing for Chinese luxury seafood value chains: Different outcomes for producers in the Philippines and North America. Mar. Policy 2015, 63, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IbisWorld. Frozen Seafood Processing in China: 23 May 2014. Available online: http://www.companiesandmarkets.com/Market/Food-and-Drink/Market-Research/Frozen-Seafood-Processing-in-China/RPT944599 (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Purcell, S.; Choo, P.Z.; Akamine, J.; Fabinyi, M. Consumer packaging and alternative product forms for tropical sea cucumbers. S. Pac. Commission Beche-de-mer Inf. Bull. 2014, 34, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, B. The Crisscrossed Agency of a Toast: Personhood, Individuation and Deindividuation in Luzhou, China. Aust. J. Anthropol. 2014, 25, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, M. Cold chain service to expand across China. Available online: http://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/26949-cold-chain-service-to-expand-across-china (accessed on 13 May 2015).

- Godfrey, M. Multinationals Link with Cold-Chain Solution Lanesync. Available online: http://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/27126-multinationals-link-with-cold-chain-solution-lanesync (accessed on 13 May 2015).

- KPMG. E-Commerce in China: Driving a New Consumer Culture. Available online: http://www.kpmg.com/CN/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Newsletters/China-360/Documents/China-360-Issue15–201401-E-commerce-in-China.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2015).

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Post-Modernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge, UK; Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, V.; Opper, S. Capitalism from Below: Markets and Institutional Change in China; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Ease of Doing Business Rankings. Available online: http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings (accessed on 15 May 2015).

- Forum on Health, Environment and Development (FORHEAD) Working Group on Food Safety. Food Safety in China: A Mapping of Problems, Governance and Research. Available online: http://www.ssrc.org/publications/view/food-safety-in-china-a-mapping-of-problems-governance-and-research/ (accessed on 3 March 2016).

- Broughton, E.I.; Walker, D.J. Policies and practices for aquaculture food safety in China. Food Policy 2010, 35, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Wild Abalone. Available online: www.australianwildabalone.com.au (accessed on 3 March 2016).

- Sadovy, Y.J. Humphead wrasse and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. SPC Live Reef Fish Inf. Bull. 2010, 19, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fabinyi, M.; Liu, N. The Chinese policy and governance context for global fisheries. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 96, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, A.; Cui, H.; Zou, L.; Clarke, S.; Muldoon, G.; Potts, J.; Zhang, H. Greening China’s Fish and Fish Products Market Supply Chains; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, M. China Cracks Down on Seafood Smuggling. Available online: http://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/27236-china-cracks-down-on-seafood-smuggling (accessed on 13 May 2015).

- Cheung, G.C.K.; Chang, C.Y. Cultural identities of Chinese business: Networks of the shark-fin business in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2011, 17, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Urban Life and Price Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buluswar, S.; Cook, S.; Stephenson, J.; Au, B.; Mylavarapu, S.; Ahmad, N. Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture in China: Scoping Opportunities for Engagement; Report prepared for the David and Lucile Packard Foundationby Dalberg Global Development Advisors, Seaweb and Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, in association with M. Siggs of Seaweb, K Short and W. Songlin of WWF and D; Jones of Sustainable Fisheries Partnership; David and Lucile Packard Foundation: Los Altos, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. Understanding China’s Fish Trade and Traceability; TRAFFIC East Asia: Hong Kong, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, M. China’s ‘Grey Trade’ Crackdown Could Change the Game for Seafood Industry. Available online: http://www.seafoodsource.com/seafood-expo-asia-2015/china-s-gray-channel-crackdown-could-change-the-game-for-seafood-industry (accessed on 2 October 2015).

- Fisheries and Food Security in China. Available online: http://fse.fsi.stanford.edu/events/fisheries_and_food_security_in_china (accessed on 3 March 2016).

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Origin | Price in CNY per jin (1 jin Equals 500 g, and Is the Standard Measure for Food in China) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live freshwater | Live freshwater | ||

| Mandarin fish | Siniperca chuatsi | Guangdong | 38/jin |

| Perch | Perca | Guangdong | 26/jin |

| Catfish | Siluriformes | Henan | 11/jin |

| Carps | Cypranidae | China | 6–11/jin |

| Snakeheads | Channidae | Guangdong | 13/jin |

| Bullfrogs | Lithobates catesbeianu | Guangdong, Fujian | 17.5/jin |

| Soft-shelled turtles | Trionychidae | Zhejiang | 17/jin |

| Live marine | Live marine | ||

| Turbot | Scophthalmidae | Shandong | 20/jin |

| Lobster | Nephropidae | Australia, NZ, South Africa, USA, Canada | Australian lobster 280–320/jin, Boston lobster 68/jin |

| Groupers | Serranidae | Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Australia, Hainan, Guangdong, Taiwan | 40–50/jin (cultured from Hainan); leopard coral grouper (imported) 3–400/jin |

| Crabs | Brachyura | Zhejiang, Australia | 30–70/jin |

| Scallops | Pectinidae | Liaoning | 20/jin |

| Clams (e.g., Venus, Razor) | Bivalvia | Liaoning | 4–10/jin |

| Ribbonfish | Trichiuridae | Zhejiang, Fujian | 60–70/jin (live), |

| Yellow Croakers | Larimichthys | Zhejiang, Fujian | 3–50/jin (farmed), 8–900 (wild-caught) |

| Frozen | Frozen | ||

| Salmon | Salmonidae | Norway, Scotland | 56/jin |

| Clams | Bivalvia | Canada | 20/jin |

| Ribbonfish | Trichiuridae | Zhejiang, Fujian | 20/jin |

| Dried | Dried | ||

| Abalone | Haliotidae | Dalian, Japan, South Africa, Australia | 1000/jin |

| Shark fin | Elasmobranchii | Hong Kong | Most common types at 400/jin |

| Sea cucumber | Holothuridae | Liaoning, Shandong | 200–3000/jin |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fabinyi, M.; Liu, N. The Social Context of the Chinese Food System: An Ethnographic Study of the Beijing Seafood Market. Sustainability 2016, 8, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030244

Fabinyi M, Liu N. The Social Context of the Chinese Food System: An Ethnographic Study of the Beijing Seafood Market. Sustainability. 2016; 8(3):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030244

Chicago/Turabian StyleFabinyi, Michael, and Neng Liu. 2016. "The Social Context of the Chinese Food System: An Ethnographic Study of the Beijing Seafood Market" Sustainability 8, no. 3: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030244

APA StyleFabinyi, M., & Liu, N. (2016). The Social Context of the Chinese Food System: An Ethnographic Study of the Beijing Seafood Market. Sustainability, 8(3), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030244