1. Introduction

As one of the globally important terrestrial ecosystems, grasslands provide livelihoods for nearly 800 million people and are a crucial source of livestock forage and wildlife habitat [

1]. With recent climate change, rapid population growth, and land-use and cover changes, three quarters of the world’s grasslands have been degraded and more than 25% of their animal support capacity has been lost [

2].

The degradation of China’s grasslands began to accelerate after the 1950s [

3]. In addition to climate, population, land use, and other driving factors, major policies in China have had a more prominent impact on grassland environments than in other regions of the world. Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, there were no clear policy constraints on farmers’ grassland management. Because grasslands were sparsely populated, farmers usually adopted a nomadic mode of production [

4]. At that time, grasslands experienced less pressure, and their natural productivity and self-recovery capability maintained ecosystem equilibrium [

5,

6]. During the period of 1950–1978, with the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the population grew rapidly. Thus, food production became one of the most important enterprises at that time. A large-scale land reclamation policy was implemented in this context [

7]. As the population increased and the conflicts between arable land and grassland intensified, the nomadic distance gradually narrowed and slowly evolved into sedentary grazing [

8]. With excessive use and lack of any protection, this led to the degradation of many grassland regions [

9,

10]. At this time, all the grassland and livestock were owned by communes. With the reform of the economic system in 1978 (the communes were replaced by a household contract responsibility system), grasslands were contracted to farmers. However, due to the higher cost of grassland fencing, most of them were not separated [

11]. Therefore, this did not change the nature of the common-pool grassland management. Livestock were also distributed to households, which greatly promoted farmers’ enthusiasm for production. The average number of livestock increased from 30 × 10

6 heads in 1949 to 100 × 10

6 in the 1990s. This led to an approximate 70% decrease in the average land area per head of livestock. This trend also caused the overall grassland area to decrease by 65 × 10

6 hm

2. This then led to a sharp decline in the quality of grassland. These factors created a vicious cycle of grassland degradation [

12].

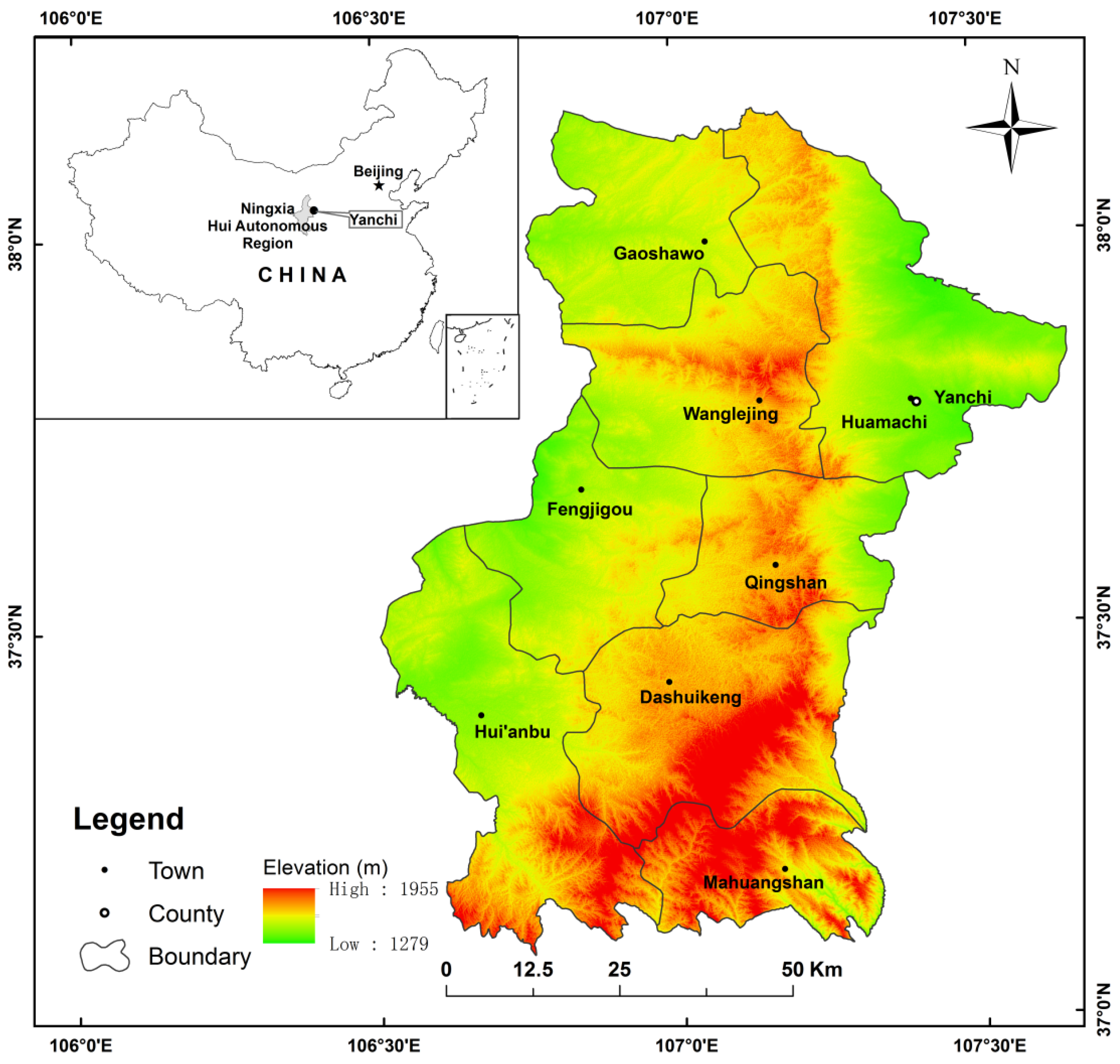

To curb the trend of grassland degradation and coordinate China’s western development strategy, the state implemented a series of policies primarily aimed at environmental protection. The grazing ban policy (GBP) is one of these policies. In 2003, a GBP was implemented in Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Qinghai, Yunnan, Sichuan, Tibet, Xinjiang, and the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (the policy was expanded to Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Hebei, and Shanxi in 2012). The main component of the policy is the fencing of seriously degraded grassland, in exchange for subsidies including feed grain (for five years) and capital grants (for the construction of grassland fencing, etc.) tailored to regional differences. By 2013, the total area of GBP implementation reached 0.96 × 108 hm2. Following the implementation of the GBP, the grassland ecological environment significantly improved. The grassland vegetation coverage, vegetation height, and fresh yield compared with areas without grazing control are 10%, 34.8%, and 53.5% higher, respectively.

The implementation area of the GBP is focused on China’s ethnic minority areas (including Hui, Mongolian, Tibetan, and Kazak minorities) where grassland is a main source of income. The vast majority of farmers have difficulty accepting these mandatory changes to their traditional means of livelihood. Moreover, according to the survey, more than 70% of farmers engaged in illegal grazing following the GBP implementation. Therefore, understanding the attitude of farmers to the GBP and their perceptions of the environment is critically important for future conservation strategies.

Previous evaluations of new or reformed rangeland policies focused more on changes in soil physical and chemical properties [

13,

14,

15,

16], grassland community characteristics [

17,

18], farmers’ livelihoods [

19,

20,

21], and farming inputs and outputs [

22,

23]. Other studies used governmental or public interview data from a small number of farmers to examine the implications of policies [

24,

25]. However, these studies are limited to cross-sectional data for one year, and there is a lack of comparative studies over different years.

In this study, household surveys were conducted over three stages (2003–2004, 2007–2008, and 2011–2012) to explore changes in farmers’ attitudes towards the GBP over time and their awareness of ecological changes after the GBP. Although there are certain discrepancies between farmers’ answers and their actual behavior, farmers’ attitudes toward the policy over time still reflect their behavior to a certain extent. This analysis also lays the groundwork to explore root causes of illegal grazing behavior.

The main objectives of this study are to: (1) identify how well farmers’ perception reflects actual environmental change; (2) follow changes in farmers’ perception over time and determine the causes of these changes; and (3) recommend improved strategies for the GBP.

4. Discussion

The development of an effective policy requires understanding the background and structure of the policy as well as considering the role of the main body of people affected. Effective incentives and management mechanisms support the implementation of the policy. Because of their high dependency on grassland, changes in rights of use directly affect farmers’ production and lifestyle. Therefore, all aspects of grassland ecosystem management should be considered when developing a grassland policy, including grasses, animals, and human beings.

In recent years, in the study of grassland resource management, adaptive management and community management have gradually garnered more attention [

26,

27,

28,

29]. These management regimes emphasize the role of resource utilization participants at different levels. The participation of the people cannot be separated from their perception and understanding of the ecological environment. Environmental perception is the psychological basis of people’s environmental behavior, and proper environmental perception is the foundation of reasonable environmental behavior [

30]. As the most important economic entities and the most basic decision-making units, the farmers’ perceptions and attitudes towards the environment reflect the changes and functions of the regional development.

Atteh (1984) [

31] showed that Nigerian farmers’ perceptions of the environment are very good, and they have a strong ability to identify pest problems and consciously conduct efficient management and decisions according to the perception of pests. Gasson and Potter (1988) [

32] found that if farmers have strong ecological protection awareness, their protective behavior is stronger. Whitby (1994) [

33] pointed out that participation in environmental planning helped farmers change their attitude towards the environment.

This study shows that farmers’ perceptions of ecological environment improvement are accurate, but they have wide-ranging comments on the GBP. According to the survey, the sheep breeding rate was higher during barn feeding than grazing periods, and the rate of return increased to a certain extent. However, farmers focused on short-term cost reduction and did not consider that after the grazing ban was lifted, the sheep breeding rate would decline to the level of the past. Thus, farmers’ perceptions of the ecological environment are closely related to their economic interests and show a certain short-term bias. Cary and Wilkinson (1997) [

34] showed that farmers’ environmental awareness does not translate into specific environmental protection behavior unless the behavior has corresponding economic benefits. The grassland utilization behavior follows, to a certain extent, the theory of the Tragedy of the Commons [

35].

Most ecological protection projects cannot immediately produce economic benefits (there are many uncertainties about the future of the project), and it is not difficult to understand why the majority of farmers with a positive environmental attitude conduct illegal grazing. Farmers have self-awareness of the illegal grazing behavior. Most of them think that the GBP policy should not be endless and that grasslands should be grazed appropriately after the reversion of grassland desertification to maintain self-renewal capacity. They engage in illegal grazing for their own interest while expressing positive attitudes towards the survival of grasslands. Many studies indicate that after degraded grassland is restored, it should be sustainably grazed. A positive feedback relationship between plant growth and livestock feed can then be gradually established. Long-term prohibition of grazing is not conducive to the regeneration of grasslands [

36,

37]. In fact, after the implementation of the GBP, despite some illegal grazing, the overall pressure on grasslands was reduced compared with periods with no government supervision. Grassland desertification reversion in Yanchi County is the result of the interaction between the GBP and farmers’ illegal grazing behavior.

5. Conclusions

This case study highlights changes in the perception of farmers over 10 years of GBP implementation. Knowledge of the policy and economic background of the study area gave us a preliminary understanding of the underlying causes of these changes. Farmers’ answers inevitably reflect strong emotions towards the long-term implementation of the GBP. Even so, the results can reflect farmers’ ideas to a certain extent via the comprehensive analysis of the data over several years. Additionally, the results provide a reference for subsequent rational policy formulation.

As can be seen from the response of farmers to the GBP, ecological awareness of farmers tends to be short term. In areas with a degraded environment, farmers were eager to implement policies to improve the environment and recognized the positive impact of the GBP. However, as conditions improved, farmers’ recognition and acceptance attitudes toward the GBP became negative. Although farmers recognize the effect of the GBP, they have little understanding of the long-term process of environmental governance. As can be seen from the attitudes of farmers toward the GBP and their ecological awareness, they are more inclined to value short-term economic interests than ecological protection.

As the direct users of grassland, farmers have a small farmers’ consciousness, but they are sensitive to the perception of the quality of resources. A good ecological policy should take into account the ecological environment and the income of the farmers. Therefore, the formulation of future policies should take into account the views of those who will be most directly affected by its implementation. Given that farmers are driven by economic interests, the government should formulate corresponding incentive mechanisms, such as grazing fees or payments based on the provision of ecosystem services.

This article is a preliminary study, and a follow-up study should include controlled experiments to explore ways to motivate farmers and realize the sustainable management and utilization of the grassland.