How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

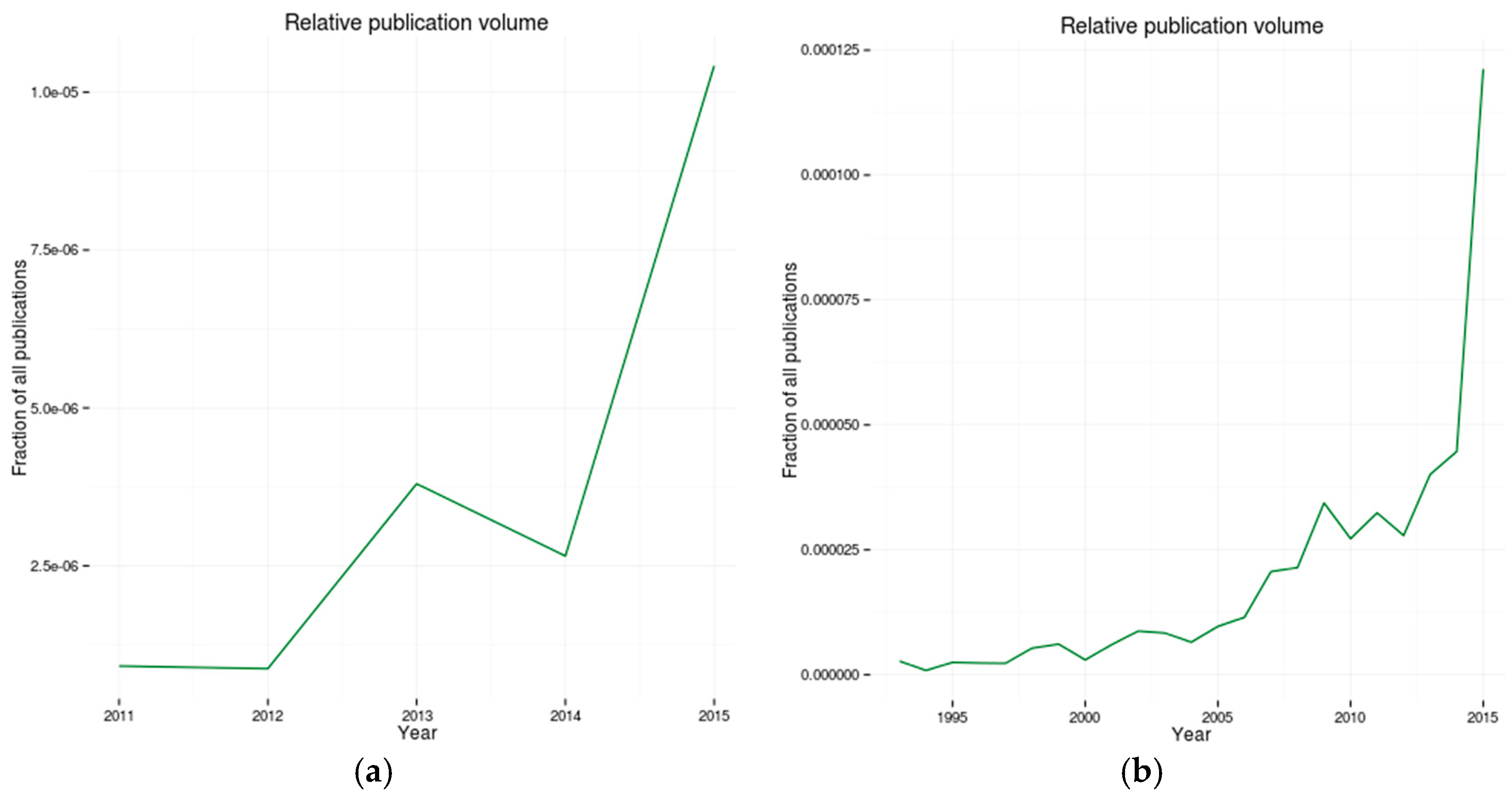

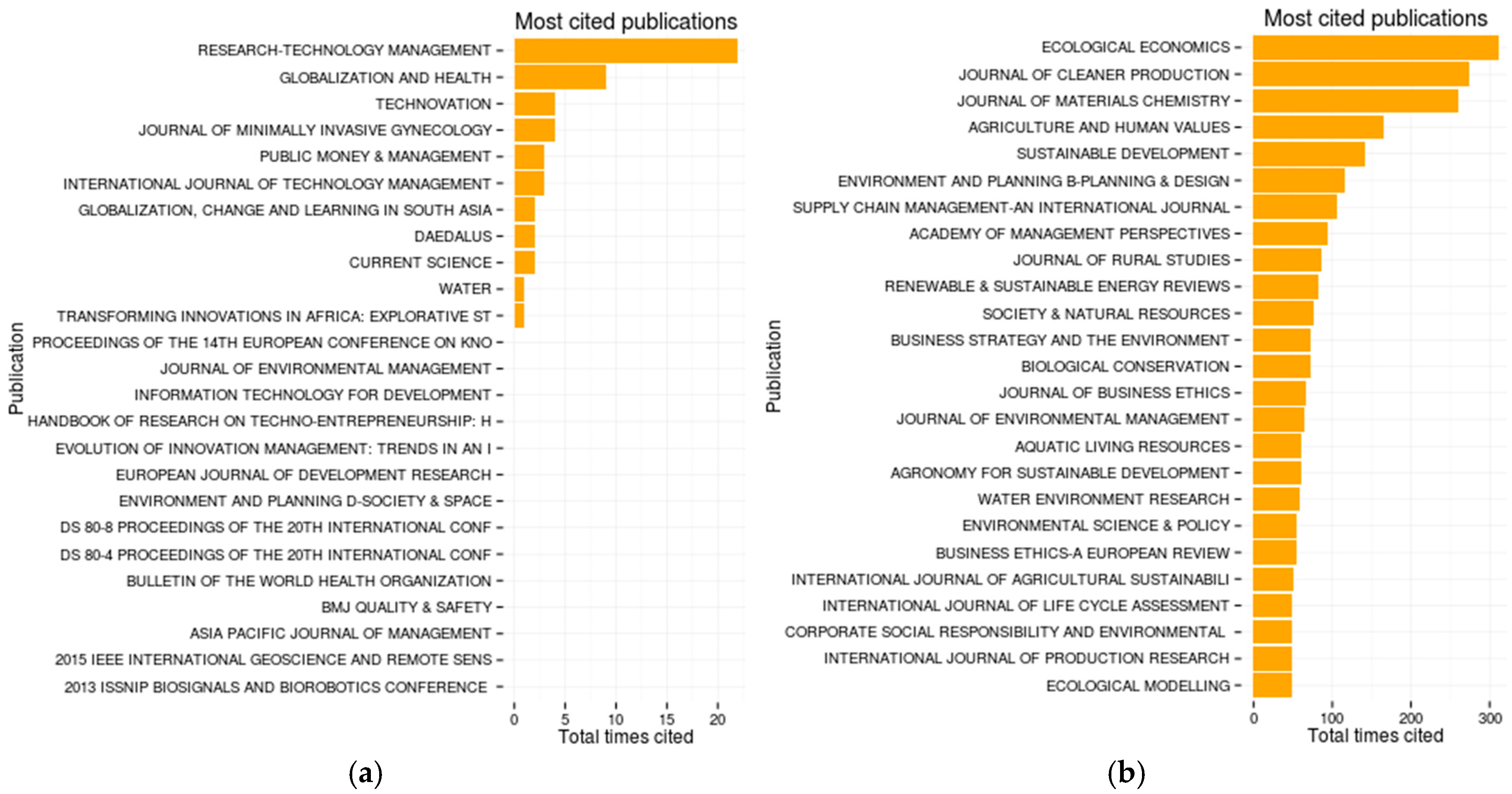

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Collection

2.2. Material Selection

2.3. Material Analysis

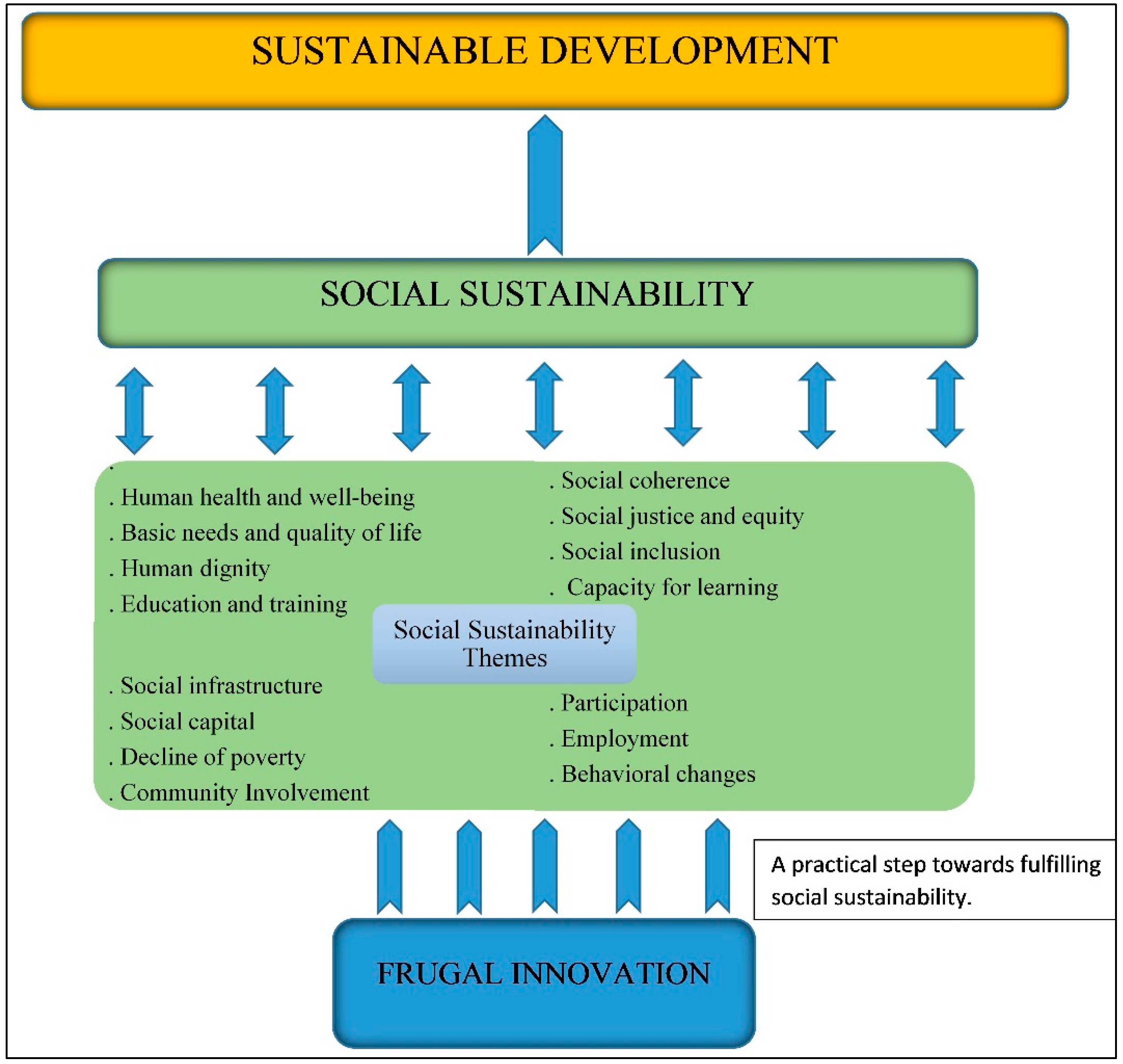

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. What Is Frugal Innovation?

3.2. What Is Social Sustainability?

3.3. Establishing a Connection between Social Sustainability and Frugal Innovation: Practical Cases of Frugal Innovation and Their Links to the Social Sustainability Themes and SDGs

3.3.1. Aravind Eye Care

3.3.2. Jaipur Foot

3.3.3. Kerala’s Palliative Care

3.3.4. Narayana Hrudayalaya

3.3.5. Vortex Engineering (Solar Powered ATMs)

3.3.6. SELCO

3.3.7. M-Pesa

3.3.8. Craftskills East Africa limited

4. Implications for Theory and Practice

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vavik, T.; Keitsch, M. Exploring relationships between Universal Design and Social Sustainable Development: Some Methodological Aspects to the Debate on the Sciences of Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M. The environmental-social interface of sustainable development: Capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, E. Social sustainability: A useful theoretical framework? In Proceedings of the Australasian Political Science Association Annual Conference, Dunedin, New Zealand, 28–30 September 2005.

- Torjman, S. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development, a Paper Prepared for Commissioner of Environment and Sustainable Development; Caledon Institute of Social Policy: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R.; Herstatt, C. India—A Lead Market for Frugal Innovations? Extending the Lead Market Theory to Emerging Economies; Working Paper No. 67; Institute for Technology and Innovation Management, Hamburg University of Technology: Hamburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone, L.D.; Popoff, F. Eco-Efficiency: The Business Link to Sustainable Development; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Porritt, J. Capitalism as if the World Matters; Earthscan: Sterling, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, D. Innovation and Growth: How Business Contributes to Society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.; Ivens, B. Do Frugal and Reverse Innovation Foster Sustainability? Introduction of a Conceptual Framework. J. Technol. Manag. Grow. Econ. 2013, 4, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Levänen, J.; Hossain, M.; Lyytinen, T.; Hyvärinen, A.; Numminen, S.; Halme, M. Implications of Frugal Innovations on Sustainable Development: Evaluating Water and Energy Innovations. Sustainability 2016, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, B.; Grießler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bound, K.; Thornton, I.W. Our Frugal Future: Lessons from India’s Innovation System; Nesta: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zeschky, M.; Widenmayer, B.; Gassmann, O. Frugal Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Case of Mettler Toledo. Res. Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeschky, M.B.; Winterhalter, S.; Gassmann, O. From Cost to Frugal and Reverse Innovation: Mapping the Field and Implications for Global Competitiveness. Res. Technol. Manag. 2014, 57, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, P. Innovation Management and New Product Development, 4th ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: Essex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Radjou, N.; Prabhu, J. Frugal Innovation: How to Do More with Less, 1st ed.; Profile Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Iyer, G.R. Resource-constrained product development: Implications for green marketing and green supply chains. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Herstatt, C. Assessing India’s lead market potential for cost-effective innovations. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2012, 4, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolridge, A. The World Turned Upside Down. Economist 2010. Available online: http://www.economist.com/node/15879369 (accessed on 20 March 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Immelt, J.R.; Govindarajan, V.; Trimble, C. How GE is disrupting itself. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, Y.A.; Ventresca, M. The Emerging Market for Frugal Innovation: Fad, Fashion, or Fit? 2012. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2005983 (accessed on 3 March 2016).

- Hart, S.; Christensen, C.M. The great leap. Driving innovation from the Base of the Pyramid. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2002, 44, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Baumann, H.; Ruggles, R.; Sadtler, T.M. Disruptive innovation for social change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schuh, G.; Lenders, M.; Hieber, S. Lean Innovation—Introducing Value Systems to Product Development. Int. J. Innov. Techol. Manag. 2011, 8, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hart, S.L. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Strategy+Business. 2002. Available online: http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~brewer/ict4b/Fortune-BoP.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2016).

- Radjou, N.; Prabhu, J.; Ahuja, S. Jugaad Innovation: Think Frugal, Be Flexible, Generate Breakthrough Growth; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Fressoli, M.; Thomas, H. Grassroots innovation movements: Challenges and contributions. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; McGahan, A.M.; Prabhu, J.; Macgahan, A. Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 662–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Herstatt, C. Frugal Innovation: A Global Networks’ Perspective in Die Unternehmung. Swiss J. Bus. Res. Pract. 2012, 66, 245–274. [Google Scholar]

- Simula, H.; Hossain, M.; Halme, M. Frugal and Reverse Innovations—Quo Vadis? Curr. Sci. 2015, 109, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, V.; Ramamurti, R. Reverse innovation, emerging markets, and global Strategy. Glob. Strategy J. 2011, 1, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, V.J.; Trimble, C. Reverse Innovation: Create Far from Home, Win Everywhere; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan, V. Reverse innovation playbook. Strateg. Direct. 2012, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Frugal and Reverse Innovation—Literature Overview and Case Study Insights from a German MNC in India and China. In Proceedings of the 2012 18th International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation, Munich University of Applied Sciences, Munich, Germany, 18–20 June 2012; Katzy, B., Holzmann, T., Sailer, K., Thoben, K.D., Eds.; Strascheg Center for Entrepreneurship (SCE): Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zeschky, M.; Widenmayer, B.; Gassmann, O. Organising for reverse innovation in Western MNCs: The role of frugal product innovation capabilities. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2014, 64, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedtwitz, M.; Corsi, S.; Søberg, P.V.; Frega, R. A typology of reverse innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobel, I. Jugaad: A New Innovation Mindset. J. Bus. Financ. Aff. 2012, 1, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtchnell, T. Jugaad as systemic risk and disruptive innovation in India. Contemp. South Asia 2011, 19, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R. From Jugaad to Systematic Innovation: The Challenge for India; Utpreraka Foundation: Bangalore, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, A.; Wolfram, P. Research and development from the bottom up-introduction of terminologies for new product development in emerging markets. J. Innov. Entrep. 2014, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, R.; Gupta, V.; Mondal, A. Jugaad—From ‘Making Do’ and ‘Quick Fix’ to an Innovative, Sustainable and Low-Cost Survival Strategy at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Int. J. Rural. Manag. 2012, 8, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, C.J.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.B. Globalizing Business Ethics Research and the Ethical Need to Include the Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Countries: Redefining the Global Triad as Business Systems and Institutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 9, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I.; Ventresca, M.J. Building Inclusive Markets in Rural Bangladesh: How Intermediaries Work Institutional voids. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 819–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, D.A.; Guesalaga, R.; Marshall, P. The quest for the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Potential and challenges. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V. Africa Rising: How 900 Million African Consumers Offer More Than You Think; Wharton School Publishing: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, V.; Banga, K.; Gunther, R. The 86 Percent Solution: How to Succeed in the Biggest Market Opportunity of the Next 50 Years; Wharton School Publishing: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abayomi, B.; Jaspar, R. Disruptive Innovations at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Can they impact on the sustainability of today’s companies? In Proceedings of the Trends and Future of Sustainable Development Conference, Tampere, Finland, 9–10 June 2011; pp. 325–336.

- Karnani, A. The Mirage of Marketing to the Bottom of the Pyramid: How the Private Sector can help Alleviate Poverty. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T. Making Better Investments at the Base of the Pyramid. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- London, T.; Hart, S.T. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the Transnational Model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansera, M.; Sarkar, S. Crafting Sustainable Development Solutions: Frugal Innovations of Grassroots Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Matos, S.; Sheehan, L.; Silvestre, B. Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the Base of the Pyramid: A Recipe for Inclusive Growth or Social Exclusion? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavul, S.; Bruton, G.D. Harnessing Innovation for Change: Sustainability and Poverty in Developing Countries. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K. Bottom of the Pyramid as a Source of Breakthrough Innovations. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Mashelkar, R.A. Innovation’s Holy Grail. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kandachar, P.; Halme, M. Introduction: An Explanatory Journey towards the Research and Practice of the Base of the Pyramid. Green. Manag. Int. 2007, 51, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, B.; Halme, M. Bringing the needs of the poor into the BOP debate. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, T.; Maritz, A.; Waal, A. Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship at the bottom of the pyramid—A Conceptual Framework. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 16, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K. The innovation sandbox. Strategy+Business. 2006. Available online: http://www.strategy-business.com/media/file/sb44_06306.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2016).

- Anderson, J.; Markides, C. Strategic Innovation at the Base of the Pyramid. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri, A. Revisiting the Debate over the Bottom of the Pyramid Market. J. Macromark. 2012, 32, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K. Grassroot Green Innovations for Inclusive, Sustainable Development. In The Innovation for Development Report 2009–2010: Strengthening Innovation for the Prosperity of Nations; López-Carlos, A., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2010; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. Innovations for the poor by the poor. Int. J. Technol. Learn. Innov. Dev. 2012, 5, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufin, C. Reviewing a Decade of Research on the ‘Base/Bottom of the Pyramid’ (BOP) Concept. Bus. Soc. 2013, 20, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. The Bottom of the Pyramid Strategy for Reducing Poverty: A Failed Promise. In Poor Poverty: The Impoverishment of Analysis; Sundaram, J.K., Chowdhury, A., Eds.; DESA, Bloomsbury Academic and United Nations: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karnani, A. Misfortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Green. Manag. J. 2007, 51, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. Doing Well by Doing Good: The Grand Illusion. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Romijn, H. The empty rhetoric of poverty reduction at the base of the pyramid. Organization 2011, 19, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.R.; Banerjee, P.M.; Sweeny, E.G. Frugal Innovation: Core Competencies to address Global Sustainability. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain. 2013, 1, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathap, G. The myth of frugal innovation in India. Curr. Sci. 2014, 106, 374–377. [Google Scholar]

- Inno. Post. What Everybody Ought to Know about Frugal Innovation. Available online: http://www.innovation-post.com/what-everybody-ought-to-know-about-frugal-innovation/#sthash.5iIrDjFs.dpuf (accessed on 21 March 2016).

- Rao, B.C. How disruptive is frugal? Technol. Soc. 2013, 35, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukerjee, K. Frugal Innovation: The Key to Penetrating Emerging Markets. Available online: http://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/frugal-innovation-the-key-to-penetrating-emerging-markets/ (accessed on 19 March 2016).

- Bhatti, Y. What Is Frugal, What Is Innovation? Towards a Theory of Frugal Innovation. 2012. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2005910 (accessed on 6 May 2016).

- Lim, C.; Han, S.; Ito, H. Capability building through innovation for unserved lower end mega markets. Technovation 2013, 3, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Krishnan, R.T. Frugal innovation: Aligning theory, practice, and public policy. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2013, 6, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angot, J.; Ple, L. Serving poor people in rich countries: The bottom-of-the-pyramid business model solution. J. Bus. Strategy 2015, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossberg, M.; Zimmerman, A. Developing Statewide Indices of Environmental, Economic and Social Sustainability: A look at Oregon and the Oregon Benchmarks. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldan, B.; Janouskova, S.; Hak, T. How to understand and measure environmental sustainability: Indicators and targets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. Strengthening the ‘social’ in sustainable development: Developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 18, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robert, K.H.; Broman, G.; Sverdrup, H. Exploring the possibility of a systematic and generic approach to social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Omann, I. Assessing social sustainability: Social sustainability and its multicriteria assessment in a sustainability scenario for Germany. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 1, 318–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, J. Social sustainability in a globalizing world context, theory and methodology explored. In Proceedings of the UNESCO/MOST Meeting, The Hague, The Netherlands, 22–23 November 2001.

- Vifell, A.C.; Soneryd, L. Organizing matters: How ‘the social dimension’ gets lost in sustainability projects. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcraft, S. Social Sustainability and New Communities: Moving from concept to practice in the UK Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vifell, A.C.; Thedvall, R. Organizing for social sustainability: Governance through bureaucratization in meta-organizations. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A. Social sustainability: Exploring the linkages between research, policy and practice. In European Research on Sustainable Development: Transformative Science Approaches for Sustainability; Jaeger, C.C., Tabara, J.D., Jaeger, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A. Social Sustainability: An Exploratory Analysis of Its Definition, Assessment Methods Metrics and Tools; EIBURS Working Paper 2007/01; Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD), Oxford Brooks University: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weingaertner, C.; Moberg, Å. Exploring social sustainability: Learning from perspectives on urban development and companies and products. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.Y.; Peacock, C.J. Social sustainability: A comparison of case studies in UK, USA and Australia. In Proceedings of the 17th Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, PRRES, Gold Coast, Australia, 16–19 January 2011.

- Davidson, M. Social sustainability: A potential for politics? Local Environ. 2009, 14, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Lamit, H.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban Social Sustainability Trends in Research Literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, N. Social sustainability and new communities: Moving from concept to practice in the UK. In Future Communities: Socio-Cultural and Environmental Challenges 2012; The Berkeley Group: Giza, Egypt, 2012; pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, I. Social Sustainability and Whole Development: Exploring the Dimensions of Sustainable Development. In Sustainability and the Social Sciences: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Integrating Environmental Considerations into Theoretical Reorientation; Egon, B., Thomas, J., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Polese, M.; Stren, R. The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Working Paper No. 27; Hawk Research Institute, University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, R. Social Sustainability, Sustainable Development and Housing Development: The Experience of Hongkong. In Housing and Social Change: East, West Perspectives; Forrest, R., Lee, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A. Urban social sustainability themes and assessment methods. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2010, 163, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G. A Strategic Approach to Social Sustainability—Part 1: Exploring the Social System. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K.; Shinn, C. Emergent themes of social sustainability. In Understanding the Social Aspect of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, G. An inquiry into the theoretical basis of sustainability: Ten propositions. In Understanding the Social Aspect of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 45–83. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, G.; Frostell, B. Social Sustainability and Social Acceptance in technology Assessment: A Case Study of Energy Technologies. Technol. Soc. 2007, 29, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E. Housing for an urban renaissance: Implications for social equity. Hous. Stud. 2003, 18, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geibler, J.; Liedtke, C.; Wallbaum, H.; Schaller, S. Accounting for the Social Dimension of Sustainability: Experiences from the Biotechnology Industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuschagne, C.; Brent, A.C. Social Indicators for Sustainable Project and Technology Life Cycle Management in the Process Industry. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2006, 11, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco, M. Social sustainability and urban mobility: Shifting to a socially responsible pro-poor perspective. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 11, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Dillard, J. Social sustainability: An Organizational—Level Analysis. In Understanding the Social Aspect of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Tirado, A.A.; Morales, M.R.; Lobato-Calleros, O. Additional Indicators to Promote Social Sustainability within Government Programs: Equity and Efficiency. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9251–9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G.; Rybchinski, T. Social Sustainability and its Indicators through a Disability Studies lens and an Ability Studies lens. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4889–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robèrt, K.H.; Broman, G. A strategic approach to social sustainability-Part 2: A principle-based definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, C.O.; Schmidheiny, S.; Watts, P. Walking the Talk: The Business Case for Sustainable Development; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W.; Sunter, C. Beyond Reasonable Greed: Why Sustainable Business Is a Much Better Idea; Human & Rousseau Tafelberg: Cape Town, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Building Sustainable Organizations: The Human Factor. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, M.J.; Sutherland, J.W. An exploration of measures of social sustainability and their application to supply chain decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, L.; Poelzer, G.A.; Ejdemo, T.; Klyuchnikova, E.; Korchak, E.; Nygaard, V. Social sustainability in northern mining communities: A study of the European North and Northwest Russia. Resour. Policy 2016, 47, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, R.V.; Klotz, L.E. Social Sustainability Considerations during Planning and Design: Framework of Processes for Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, F.A.; Stevenson, M.; Zorzini, M. Social sustainability in developing country suppliers. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 610–638. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgreen, A.; Antioco, M.; Harness, D.; van Sloot, R. Purchasing and Marketing of Social and Environmental Sustainability for High-Tech Medical Equipment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Dillard, J.; Marshall, R.S. Triple Bottom Line: A Business Metaphor for a Social Construct; School of Business Administration, Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Magee, L.; Scerri, A.; James, P.; Thom, J.A.; Padgham, L.; Hickmott, S.; Deng, H.; Cahill, F. Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.F.; Park, C.L. Self-claimed sustainability: Building social and environmental reputations with words. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Labuschagne, C.; Brent, A.C.; van Erck, R.P.G. Assessing the sustainability performances of industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, M.W.; Jorna, R.J.; van Engelen, J. Sustainability Quotients and the Social Footprint. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2008, 15, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, K.; King, M.C. Working out Social Sustainability on the Ground. In Understanding the Social Aspect of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Measuring Impact: Subject Paper of the Impact Measurement Working Group. Available online: http://www.socialimpactinvestment.org/reports/Measuring%20Impact%20WG%20paper%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2016).

- So, I.; Staskevicius, A. Measuring the Impact in Impact Investing. Available online: http://www.hbs.edu/socialenterprise/Documents/MeasuringImpact.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2016).

- Best, H.; Harji, K. Guidebook for Impact Investors: Impact Measurement. Available online: http://purposecap.com/wp-content/uploads/Purpose-Capital-Guidebook-for-Impact-Investors-Impact-Measurement.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2016).

- Galuppo, L.; Gorli, M.; Scaratti, G.; Kaneklin, C. Building social sustainability: Multi-stakeholder processes and confiict management. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 10, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, K. Sustainability and Performance. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fisk, P. People, Planet, Profit: How to Embrace Sustainability for Innovation and Business Growth; Kogan Page Limited: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, M. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, H.; Price, A.; Moobela, C.; Mathur, V. Assessing urban social sustainability: Current capabilities and opportunities for future research. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. 2007, 3, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, C. Measuring Corporate Social and Environmental Performance: The Extended Life-Cycle Assessment. J. Bus. Ethics. 2005, 59, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzil, D.; Beloff, B. Assessing Impacts: Overview on Sustainability Indicators and Metrics: Tools for Implementing Sustainable Development in the Chemical Industry, and Elsewhere. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 15, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Urban Regeneration and Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, D.S.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Antons, D.C.; Munoz, P.; Bai, X.; Fragkias, M.; Gutscher, H. A vision for human well-being: Transition to social sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, J.; Morgan, B. Sustainability Appraisal: A Social Perspective. In Sustainability Appraisal. A Review of International Experience And Practice; Dalal-Clayton, B., Sadler, B., Eds.; First Draft of Work in Progress; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ancell, S.; Thompson-Fawcett, M. The social sustainability of medium density housing: A conceptual model and Christchurch case study. Hous. Stud. 2008, 23, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carew, A.L.; Mitchell, A.A. Teaching sustainability as a contested concept: Capitalizing on variation in engineering educators’ conceptions of environmental, social and economic sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. The Social Pillar of Sustainable Development: A Literature Review and Framework for Policy Analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting them Together into Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G.R. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; IDS Discussion Paper 296; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thin, N.; Lockhart, C.; Yaron, G. Conceptualising Socially Sustainable Development. Unpublished work. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, M. Urban Policy Engagement with Social Sustainability in Metro Vancouver. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketschau, T.J. Social Justice as a Link between Sustainability and Educational Sciences. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15754–15771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.; Wilson, L. A Critical Assessment of Urban Social Sustainability; Working Paper; The University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Lee, K. Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magis, K. Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, W.B.; Kecskes, K. Social Capital and Community: University Partnerships. In Understanding the Social Aspect of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 248–263. [Google Scholar]

- Semenza, J.C. Advancing Social Sustainability: An Intervention Approach. In Understanding the Social Aspect of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 264–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.; Gardner, K.; Carlson, C. Social capital and walkability as social aspects of sustainability. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3473–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Husseiny, M.; Kesseiba, K. Challenges of Social Sustainability in Neo-liberal Cairo: Requestioning the role of public space. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocak, M.; Hospers, G.; Reverda, N. Searching for Social Sustainability: The Case of the Shrinking City of Heerlen, The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, S.U. Community based urban development: A strategy for improving social sustainability. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1999, 26, 327–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Demsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C. What is Social Sustainability and how do our existing urban forms perform in nurturing it? In Proceedings of the Planning Research Conference, Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, London, UK, 5–7 April 2006.

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District—Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, H.K.E.; Chan, H.W.E. Critical social sustainability factors in urban conservation: The case of the central police station compound in Hong Kong. Facilities 2012, 30, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcraft, S.; Hackett, T.; Caistor-Arendar, L. Design for Social Sustainability: A Framework for Creating Thriving New Communities; Young Foundation: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aravind Eye Care System. Available online: http://www.aravind.org/ (accessed on 3 April 2016).

- Kumar, S. Kerala, India, A regional community-based palliative care model. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2007, 33, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vortex. Available online: http://vortexindia.co.in/ (accessed on 21 February 2016).

- SELCO: Solar Lighting for the Poor. Available online: http://www.growinginclusivemarkets.org/media/cases/India_SELCO_2011.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2016).

- Solar Electric Light Company, India (SELCO). Available online: http://www.selco-india.com/pdfs/corporate_brochure_selco.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2016).

- Hughes, N.; Lonie, S. “M-PESA: Mobile Money for the unbanked,” Turning Cellphones into 24-Hour Tellers in Kenya. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2007, 2, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. The Economics of M-PESA. 2011. Available online: http://www.mit.edu/~tavneet/M-PESA.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2016).

- Buku, M.W.; Meredith, M.W. Safaricom and M-PESA in Kenya: Financial Inclusion and Financial Integrity. Wash. JL Tech. Arts 2013, 8, 375–399. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J. Craftskills East Africa Limited. In Cases with a Conscience: Entrepreneurial Solutions to Global Challenges; Dean, T.J., Birnbaum, M.D.M., Eds.; Sustainable Venturing Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2009; pp. 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaens, P.; de Lange, D. Field Structuration around New Issues: Clean Energy Entrepreneurialism in Emerging Economies. 2012. Available online: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/94215/1180_Adriaens.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 26 September 2016).

- Sustainability through Frugality. Available online: http://newglobal.aalto.fi/sustainability-through-frugality/ (accessed on 26 September 2016).

| Author | Characteristics | Implications for Society |

|---|---|---|

| Prahalad [42] | Price Performance Innovation: Hybrids Scale of operations Eco-friendly Identifying functionality Process innovation Deskilling of work Education of customers Designing for hostile infrastructure Interfaces Distribution: accessing the customer Unconventional way to deliver products | Making four billion poor people as customers and treating them as self-respecting citizens by understanding the fundamental needs of the BOP population and innovating for them. Building capacity for people to escape poverty and deprivation. Tackles basic needs, social inclusion, human dignity, participation. |

| Tiwari and Herstatt [5] | Affordable Robust User-friendly Easy to use Minimal use of raw materials Acceptable quality standard | Uplifting the standard of living of individual communities to the next better level. Tackles human well-being, quality of life, dealing with poverty. |

| Basu, Banerjee and Sweeny [70] | Ruggedization Light weight Mobile enabled solutions Human centric design Simplification New distribution models Adaptation Use of local resources Green technology Affordability | Needs and context of poor citizens in the developing world are put first in order to develop appropriate, adaptable, affordable and accessible solutions for them. Tackles social coherence, equity, social justice. |

| Rajdou, Prabhu and Ahuja [26] | Creative improvisation Innovation based on constraints Unusual skillset and mindset Flexibility Simplicity Social Inclusion | Innovating for the margins of the society and bringing them into the mainstream. Tackles social inclusion, social justice. |

| Rao [73] | No frills, low cost products/services robust, sustainable design, ease of use, Strong tendency to disrupt incumbents. | Innovating to harness frugality and improve profitability in a world conscious of cost and sustainability. Tackles human well-being and dealing with poverty. |

| Govindarajan and Trimble [32] | Clean-slate innovations (developed from scratch in the developing world) | Closing the wide gaps between the rich and the poor world. Tackles equity and social justice. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Authors |

|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | Boström [137], Polese and Stren [99], Magis and Shinn, [106], Chiu [101], McKenzie [100], Castillo et al. [138], Dempsey et al. [94], Gauthier [139], Geibler et al. [110], Tanzil and Beloff [140], Colantonio and Dixon [141], Rogers et al. [142], Partridge [3] |

| Basic needs and quality of life | Littig and Grießler [11], Polese and Stren [99], McKenzie [100], Magis and Shinn [106], Spangenberg and Omann [84], Baines and Morgan [143], Ancell and Thompson-Fawcett [144], Colantonio [102], Dempsey et al. [94], Carew and Mitchell [145], Partridge [3] |

| Social Coherence | Littig and Grießler [11], McKenzie [100], Vallance, Perkins and Dixon [104], Murphy [146] |

| Social justice and equity | Cuthill [82], Dempsey et al. [94], Littig and Grießler [11], McKenzie [100], Magis and Shinn [106], Vallance, Perkins and Dixon [104], Giddings, Hopwood and O’Brien [147], Spangenberg and Omann [84], Murphy [146], Chambers and Conway [148], Thin et al. [149], Koning [85], Chiu [101], Sachs [98], Holden [150], Baines and Morgan [143], Polese and Stren [99], Partridge [3], Ketschau [151] |

| Democratic/engaged government and democratic society | Cuthill [82], Magis and Shinn [106], Sachs [98], McKenzie [100], Larsen [107], Davidson and Wilson [152], Dempsey et al. [94] |

| Human rights | Bebbington and Dillard [113], Vavik and Keitsch [1], Sachs [98] |

| Social inclusion | Polese and Stren [99], Larsen [107], Davidson and Wilson [152], Ancell and Thompson-Fawcett [144], McKenzie [100], Dempsey et al. [94], Bramley and Power [153], Glasson and Wood [103], Partridge [3] |

| Diversity | Vavik and Keitsch [1], Polese and Stren [99], McKenzie [100], Spangenberg and Omann [84], Baines and Morgan [143] |

| Decline of poverty | Vavik and Keitsch [1], Vallance, Perkins and Dixon [104] |

| Social infrastructure | Cuthill [82], Chan and Lee [154] |

| Social capital | Cuthill [82], Lehtonen [2], Magis [155], Messer and Kecskes [156], Semenza [157], Baines and Morgan [144], Dempsey et al. [94], Vavik and Keitsch [1], Rogers, Gardner and Carlson [158], El-Husseiny and Kesseiba [159], Bramley and Power [153], Rocak, Hospers and Reverda [160], Colantonio and Dixon [141] |

| Behavioural changes | Vallance, Perkins and Dixon [104] |

| Preservation of socio-cultural patterns and practices | Vavik and Keitsch [1], Vallance, Perkins and Dixon [104], Davidson and Wilson [152], Colantonio and Dixon [141] |

| Participation (Including stakeholder participation) | Littig and Grießler [11], Boström [137], Giddings, Hopwood and O’Brien [147], Spangenberg and Omann [84], Murphy [146], Thin et al. [149], Baines and Morgan [143], U.O’Hara [161], Bramley et al. [162], Dempsey et al. [94], Vavik and Keitsch [1], Galuppo et al. [134], Funk [135], Lindgreen et al. [124], Labuschagne, Brent and Erck [128], Brown, Dillard and Marshall [125], Colantonio and Dixon [141], Partridge [3] |

| Human dignity | Littig and Grießler [11], Larsen [107], Vavik and Keitsch [1] |

| Safety and security | Thin et al. [149], Bramley et al. [162], Dempsey et al. [94], Vavik and Keitsch [1], Glasson and Wood [103], Gauthier [139], Geibler et al. [110], Tanzil and Beloff, [140] |

| Sense of place and belonging | Bramley et al. [162], Dempsey et al. [94], Glasson and Wood [103], Bramley and Power [153], Colantonio and Dixon [141], Yung, Chan and Xu [163], Yung and Chan [164] |

| Education and training | Spangenberg and Omann [84], Dempsey et al. [94], Colantonio and Dixon [141] |

| Employment | Sachs [98], Spangenberg and Omann [84], Dempsey et al. [94] |

| Community involvement and development, community resilience | Bramley et al. [162], Woodcraft, Hackett, and Caistor-arendar [165], Castillo et al. [138], Bramley and Power [153], Colantonio [102], Landorf [95], Magis [155], U. O’Hara [161] |

| Fair operating practices | Bebbington and Dillard [113] |

| Capacity for learning | Larsen [107] |

| No structural obstacles (to health, influence, competence, impartiality and meaning-making) | Missimer, Robert and Broman [116] |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (Aravind Eye Care) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | The eyesight of 45 million people worldwide has been snatched away, often needlessly [42]. Eradication of needless blindness contributes to human well-being. | SDG 3: Aravind Eye Care ensures healthy lives and promotes well-being by providing eyesight to millions of people. SDG 8: Aravind Eye Care promotes sustained inclusive and sustainable economic growth and provides productive employment to numerous people. SDG 9: Aravind Eye Care has built a resilient infrastructure. It promotes inclusive and sustainable eye care and fosters innovation. SDG 10: Aravind Eye Care reduces inequality within the country by empowering blind people with the gift of eye sight. SDG 12: By employing sustainable Aravind Eye Care model, each doctor at Aravind Eye Care performs about 2600 surgeries per year. SDG 16: Aravind Eye Care has emerged as a highly effective and inclusive institution, which promotes social inclusion. |

| Basic needs and quality of life | By empowering the blind people with the precious gift of eyesight, their quality of life improves. | |

| Social coherence | By seeking out and catering to the poor blind population and providing them with free treatment, social coherence is being achieved. | |

| Social justice and equity | Both rich and poor receive this treatment. Poor patients who would otherwise spend their lives in blindness receive the wondrous gift of eyesight free of cost. | |

| Social inclusion | By empowering poor and marginalized people with eyesight, Aravind Eye Care eradicates needless blindness thereby promoting social inclusion. | |

| Decline of poverty | Poor people regain their sight and receive another opportunity to earn a living. | |

| Social infrastructure | Aravind Eye Hospital accommodates social services thereby making it an excellent example of social infrastructure. | |

| Social capital | Community accountability and participation, which are distinct indicators of social capital, are clearly evident. | |

| Participation | Marginalized people are given a second chance at becoming contributing members of society. | |

| Human dignity | People regain their sight and are able to live a productive life. | |

| Employment | Aravind Eye Care caters to the problem of unemployment by employing numerous people in India. | |

| Education and training | Aravind Eye Care collaborates with the World Health Organization to design and offer structured training programmes to eye care professionals at all levels. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (Example: Jaipur Foot) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | Empowering the poor by allowing them to take control of their lives. | SDG 3: Jaipur Foot ensures healthy lives and promotes well-being by serving amputees. SDG 10: The Jaipur Foot reduces inequality within the country by empowering amputees with a prosthetic foot and allowing them to lead a more productive life. |

| Basic needs and quality of life | Amputees who receive Jaipur Foot have a better quality life. | |

| Social coherence | Promotes solidarity by helping poor sections of society. | |

| Social justice and equity | Rich and poor alike receive this treatment. Poor people, who have no means to afford expensive prosthetics, can still receive the Jaipur Foot free of charge. | |

| Social inclusion | Social inclusion is about closing the distance that separates people; this frugal innovation does just that by allowing the amputees to live a more productive life. | |

| Decline of poverty | People have better employment prospects to therefore support their families. | |

| Social infrastructure | The organization offering Jaipur Foot to the disabled, Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti (BMVSS) is the world’s largest organisation serving the disabled and a great example of a social infrastructure. | |

| Participation | Poor people who lose their limbs become unable to provide for themselves and their families; however, with the help of the Jaipur Foot, they are able to participate in society, despite their limitations. | |

| Human dignity | It empowers people and helps them continue their lives with dignity. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (Example: Kerala’s Palliative Care) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | Social care delivered to the chronically ill by volunteers from the local community is an excellent example of promoting human health and well-being. | SDG 3: Kerala’s Palliative Care promotes the well-being of severely sick people. SDG 16: Kerala’s Palliative Care is an inclusive institution that works on the principles of social inclusion and social justice. |

| Basic needs and quality of life | Through Kerala’s Palliative Care, quality of life of the acutely sick people is improved. | |

| Social coherence | It is an excellent example of social coherence, where importance of community is recognized. | |

| Social justice and equity | Through palliative care, access to basic services for health and well-being to all sick people, irrespective of their differences in status, religion or creed is possible. | |

| Social inclusion | It promotes inclusion at the level of individuals, groups and society. | |

| Social infrastructure | Kerala’s Palliative Care is an excellent example of a social infrastructure delivered through communities. | |

| Social capital | It shows community accountability, responsibility, compassion and social service. | |

| Behavioral/Attitude changes | Thinking selflessly about the old and sick members of the society and working towards the welfare of the society is the attitude that all communities need. | |

| Preservation of socio-cultural patterns and practices | This innovation preserves the socio-cultural practices of old India, which urban India has forgotten over time. Collectivism has been the essence of Indian culture. | |

| Participation | Approximately 5000 community volunteers participate in community welfare without a salary and care for more than 6000 patients. | |

| Human dignity | Palliative care aids chronically ill people and helps them live the rest of their lives with hope. | |

| Community involvement and development | It is an excellent example of how a community can get involved to deliver social care. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (Narayana Hrudayalaya) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | Offering world class cardiac care at radically low cost promotes human well-being by all means. | SDG 3: Narayana Hrudayalaya ensures healthy lives and promotes well-being. SDG 8: Narayana Hrudayalaya promotes sustained inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and provides productive employment to numerous people. SDG 9: Narayana Hrudayalaya has built resilient infrastructure, promoted inclusive and sustainable world class cardiac care at radically low cost and has employed a highly innovative healthcare model. SDG 10: Narayana Hrudayalaya reduces inequality within the country by operating people free of cost. SDG 12: Narayana Hrudayalaya represents an excellent case of sustainable production and consumption; it drastically lowers heart surgery costs through employing the principles of mass production and lean manufacturing. SDG 16: Narayana Hrudayalaya has emerged as a highly effective and inclusive institution that promotes social inclusion. |

| Basic needs and quality of life | By allowing access to the best healthcare, even to those who otherwise cannot afford it, Narayana Hrudayalaya improves quality of life. | |

| Social coherence | Offering free cardiac care to thousands of patients, social coherence is being achieved. | |

| Social justice and equity | Both rich and poor receive this treatment. Poor patients who otherwise cannot dream of highly expensive surgeries, such as those performed in the US, receive it free of charge in India. | |

| Social inclusion | By curing poor and marginalized people, Narayana Hrudayalaya promotes social inclusion. | |

| Decline of poverty | Poor people regain their health and get an opportunity to earn a living again. | |

| Social infrastructure | Narayana Hrudayalaya accommodates social services thereby making it an excellent example of a social infrastructure. | |

| Social capital | Community accountability and participation which are distinct indicators of social capital are clearly evident. | |

| Participation | By providing a micro-insurance scheme that allows poor people to access quality healthcare at INR 5 (11 cents) per month, Narayana Hrudayalaya promotes participation. | |

| Human dignity | Poor people get a chance to live their lives with dignity. | |

| Employment | Narayana Hrudayalaya provides employment to numerous people. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (Vortex Engineering ATMs) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Social inclusion | It promotes social inclusion by providing the BOP population with easy access to ATM technology. | SDG 9: Vortex Engineering is considered a highly innovative company, which designs highly reliable and eco-friendly technology. SDG 10: It gives poor people an opportunity to use ATMs, even if they are illiterate. SDG 12: Solar powered ATMs are the most sustainable ATMs made; they consume approximately 10% of the total energy of a conventional ATM and reduce CO2 emissions by at least 18,500 kg per annum [29]. |

| Social justice and equity | It provides poor people with an opportunity to use technology. | |

| Basic needs and quality of life | The quality of life of rural population improves. | |

| Capacity for learning | Provides illiterate people a chance to learn to operate previously unfamiliar technology and build new skills. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (SELCO) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | Less dependency on conventional non-renewable energy resources has a positive effect on the health and well-being of people. | SDG 3: SELCO ensures good health and well-being by enabling people to use clean energy instead of traditional fossil fuels. SDG 4: Due to uninterrupted power supply, poor students have an increased opportunity to spend more hours studying in the evenings. SDG 7: Solar power is a renewable, non-polluting energy resource. In the absence of such an inclusive business model, it would not have been possible to involve the BOP population as consumers. SDG 8: SELCO has promoted sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth and provided employment to many. SDG 9: SELCO’s innovative potential and inclusive business model have been appreciated worldwide. This is evident from the fact that the founder of SELCO received the ‘Asian. Nobel Prize’ in 2011 as well as the Ashden Award and the Outstanding Achievement Award [12,170]. SDG 10: SELCO has been successful in reducing inequality in society by enabling poor customers to build links to financial institutions and enabling them to use solar electric systems. |

| Basic needs and quality of life | 44% of the Indian population lack electricity. SELCO has provided reliable electricity to millions who otherwise had no or limited access to electricity. This has resulted in a better quality of life. Further, working for longer hours has a positive impact on the income level of BOP population. | |

| Social justice and equity | Provided an opportunity to BOP population to become respected customers. | |

| Social inclusion | Enabled the poorest segments of the population to buy solar electric systems through an innovative business model. Electricity enables them to work for longer hours, which was previously impossible. | |

| Behavioral changes | Shifting to green energy has resulted in promotion of ecofriendly behavior. | |

| Education and training | Poor students who had no or limited access to electricity in the evenings can now study longer. | |

| Employment | SELCO has not only provided employment to its own employees but also to many rural entrepreneurs who rent out solar lights to vendors and institutions. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (M-Pesa) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Basic needs and quality of life | M-Pesa has improved the quality of life of millions of BOP customers by empowering them with branchless banking service. | SDG 1: M-Pesa has reduced poverty in the regions of its operation. SDG 3: M-Pesa has been involved with Bridge International Academy which provides education to poorest areas of Kenya at a very low cost ($4 in monthly tuition per student). SDG 8: M-Pesa has promoted sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth. SDG 9: M-Pesa is a highly innovative solution, which has dramatically improved the lives of millions of people. SDG 10: M-Pesa has succeeded in reducing inequality in society by enabling BOP customers to build links to financial services. SDG 12: M-Pesa is an excellent case of sustainable mobile phone based financial service. |

| Social justice and equity | It provides an opportunity to millions of poor people to become respected customers. | |

| Social inclusion | It promotes social inclusion by providing the poor population with an access to financial services that they were otherwise devoid of. | |

| Decline of poverty | M-Pesa program has transferred more than US $1.4 trillion in electronic funds and significantly contributed to poverty alleviation [173]. | |

| Capacity for learning | It provides people with an opportunity to operate mobile phone technology and build new skills. | |

| Safety and security | Research has indicated that services like M-Pesa might play a significant role in anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing efforts [173]. It is also a safe alternative to travelling with large amounts of cash. | |

| Human dignity | This service has improved the lives of millions of Kenyans. | |

| Participation (Including stakeholder participation) | Since the launch of M-Pesa in 2007, over 15 million users have been using the service [173]. |

| Themes of Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability through Frugal Innovations (Craftskills East Africa Limited) | Promotion of SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | Use of wind power has positive health benefits compared to non-renewable energy resources. | SDG 3: Craftskills ensures good health and well-being by enabling people to use clean wind energy instead of traditional fossil fuels. SDG 7: Wind power is a renewable, non-polluting energy resource. Craftskills ensures access to affordable, reliable and clean energy to Kenyan people. SDG 9: Craftskills’ ability to generate frugal innovation in a resource constrained environment and create more from less is a step towards building resilient infrastructure. SDG 10: Craftskills has been successful in reducing inequality in society by providing poor people an access to electricity. |

| Basic needs and quality of life | Craftskills has provided clean electricity to people who otherwise had no or limited access to electricity. They have also supported farms by selling them electricity equipment for water pumps used for agricultural purposes. | |

| Social justice and equity | It provides an opportunity to BOP population to become respected customers. | |

| Social inclusion | Poor segments of population get an opportunity to buy reliable wind turbines at low costs and electrify their homes. | |

| Behavioral changes | In Africa, renewable energy is perceived as second class [175]. Motivating people to use electricity generated through green wind energy turbines is a positive behavioural change that promotes ecofriendly behaviour. | |

| Human dignity | Electrifying villages or supplying power to schools, health facilities, market places or hotels has changed the lives of people in BOP market like Kenya. |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, R. How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101034

Khan R. How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability. 2016; 8(10):1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101034

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Rakhshanda. 2016. "How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability" Sustainability 8, no. 10: 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101034

APA StyleKhan, R. (2016). How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability, 8(10), 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101034