Testing Silica Fume-Based Concrete Composites under Chemical and Microbiological Sulfate Attacks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

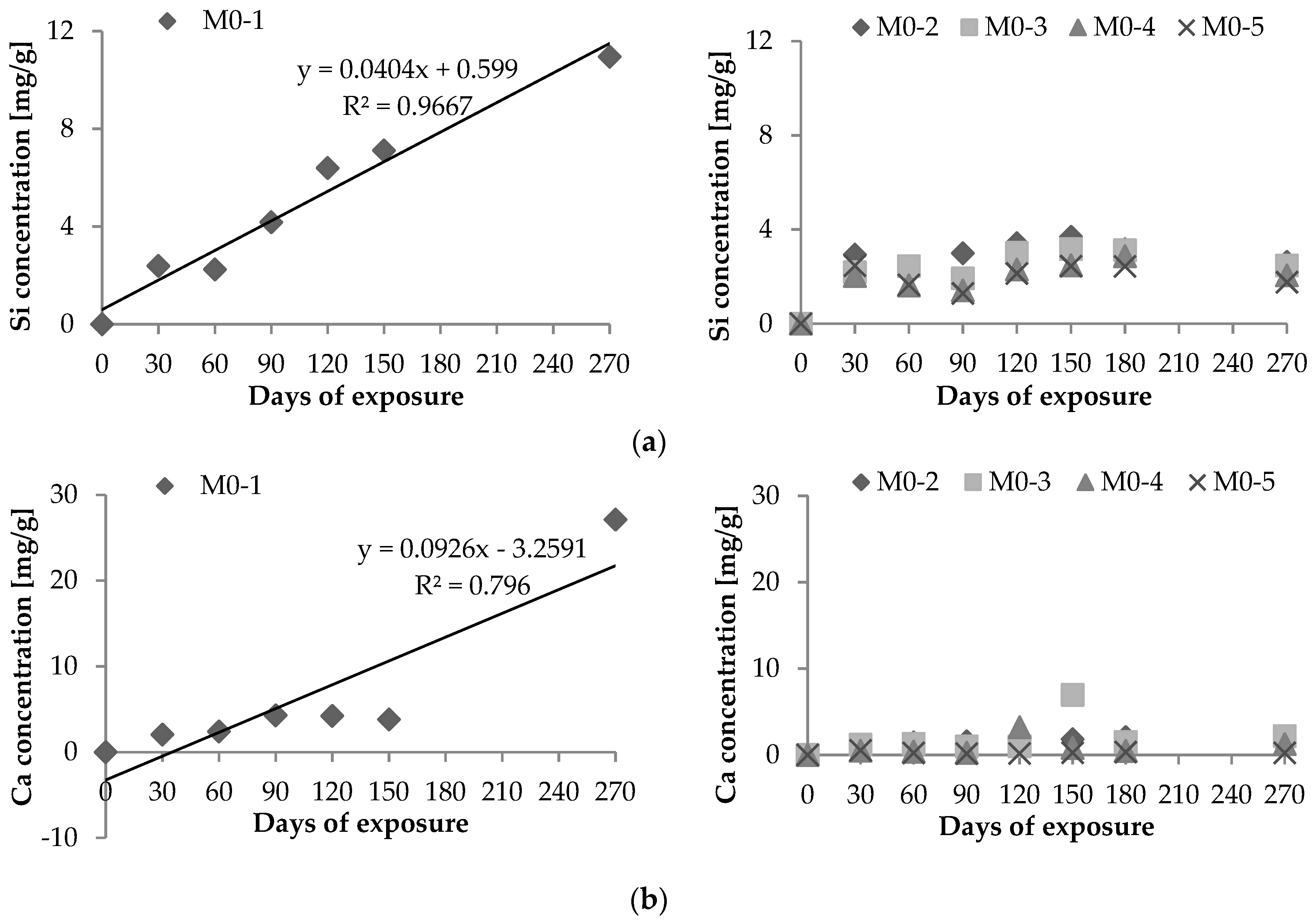

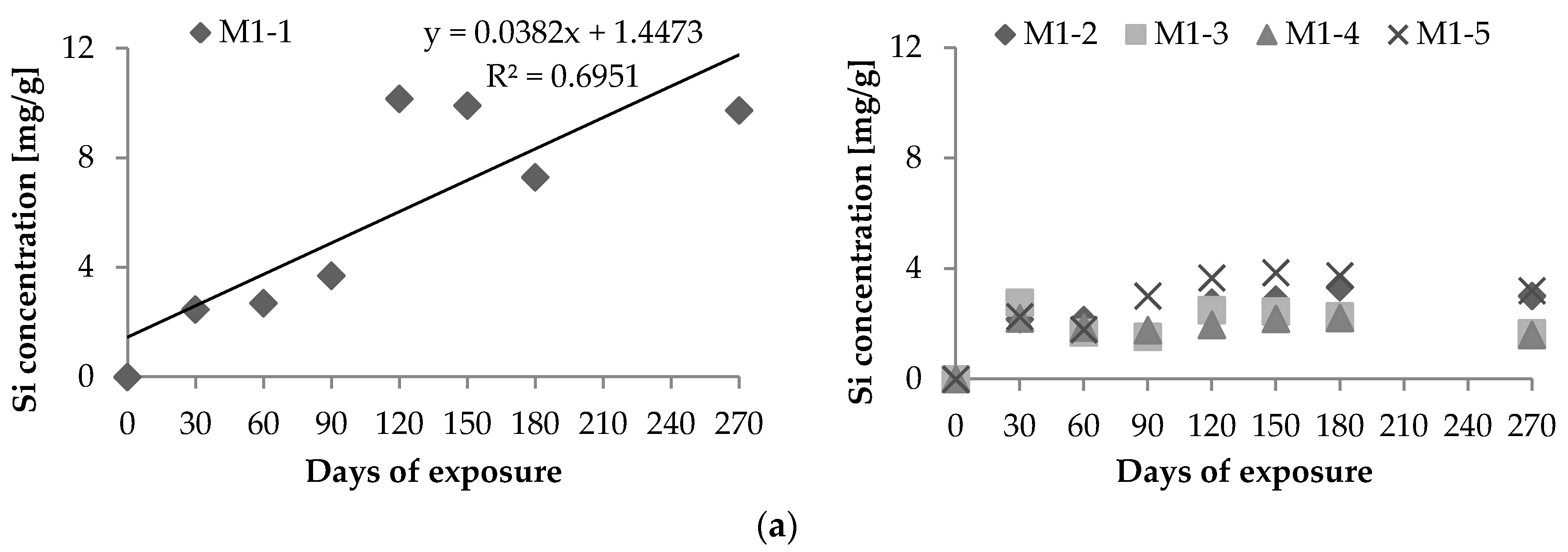

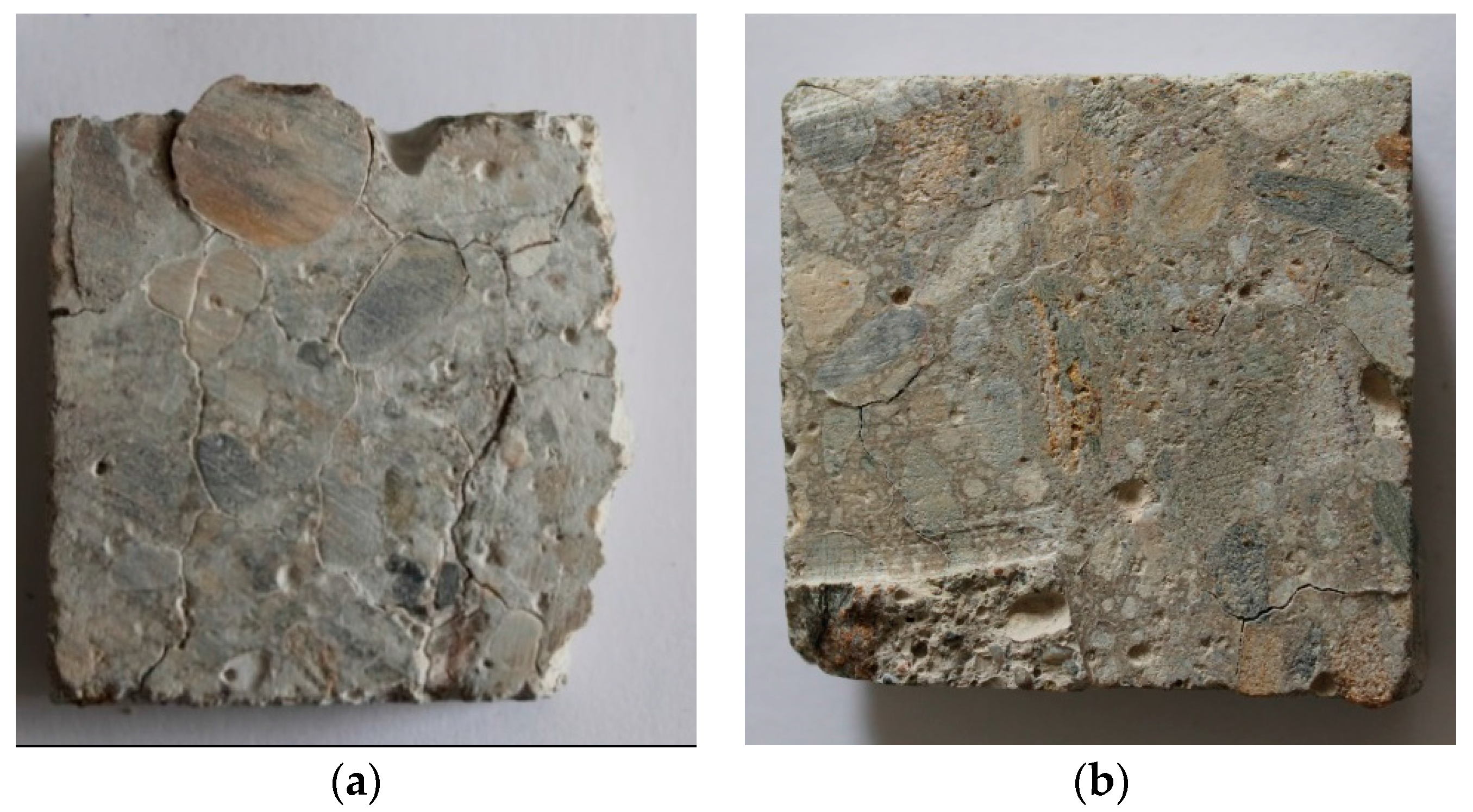

2.1. Chemical Leaching of Si4+ and Ca2+

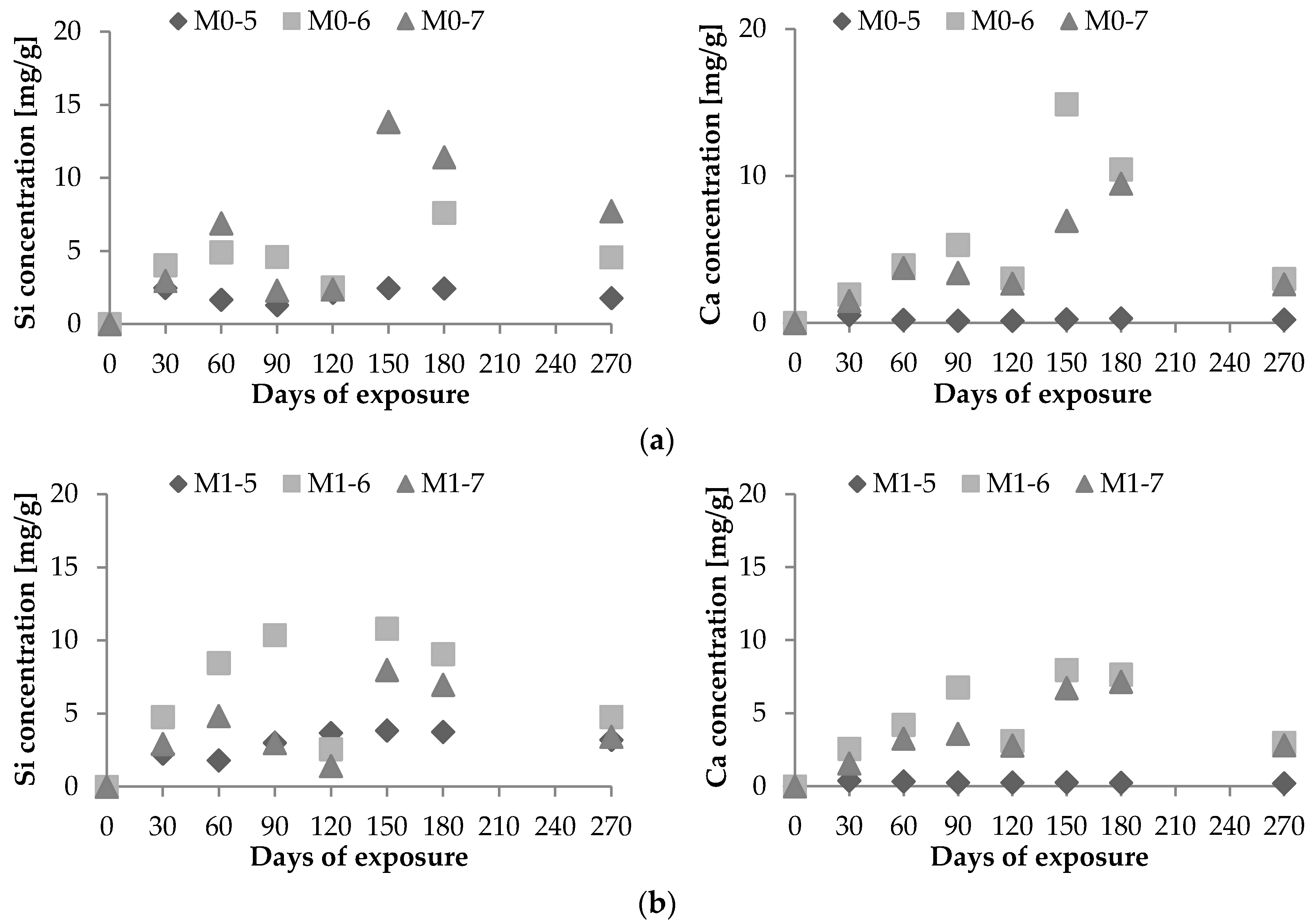

2.2. Biological Leaching of Ca2+ and Si4+

2.3. Comparison of Chemical and Biological Corrosion

- Vd: Si4+ (or Ca2+) leaching rate per unit area (μg·h−1·cm−2);Xd: maximum amount of Si4+ (or Ca2+) leached out during the experiment (μg);T: period of test [=24 × days of leaching (hours)]; andS: area of exposure surface (cm2).

3. Materials and Methods

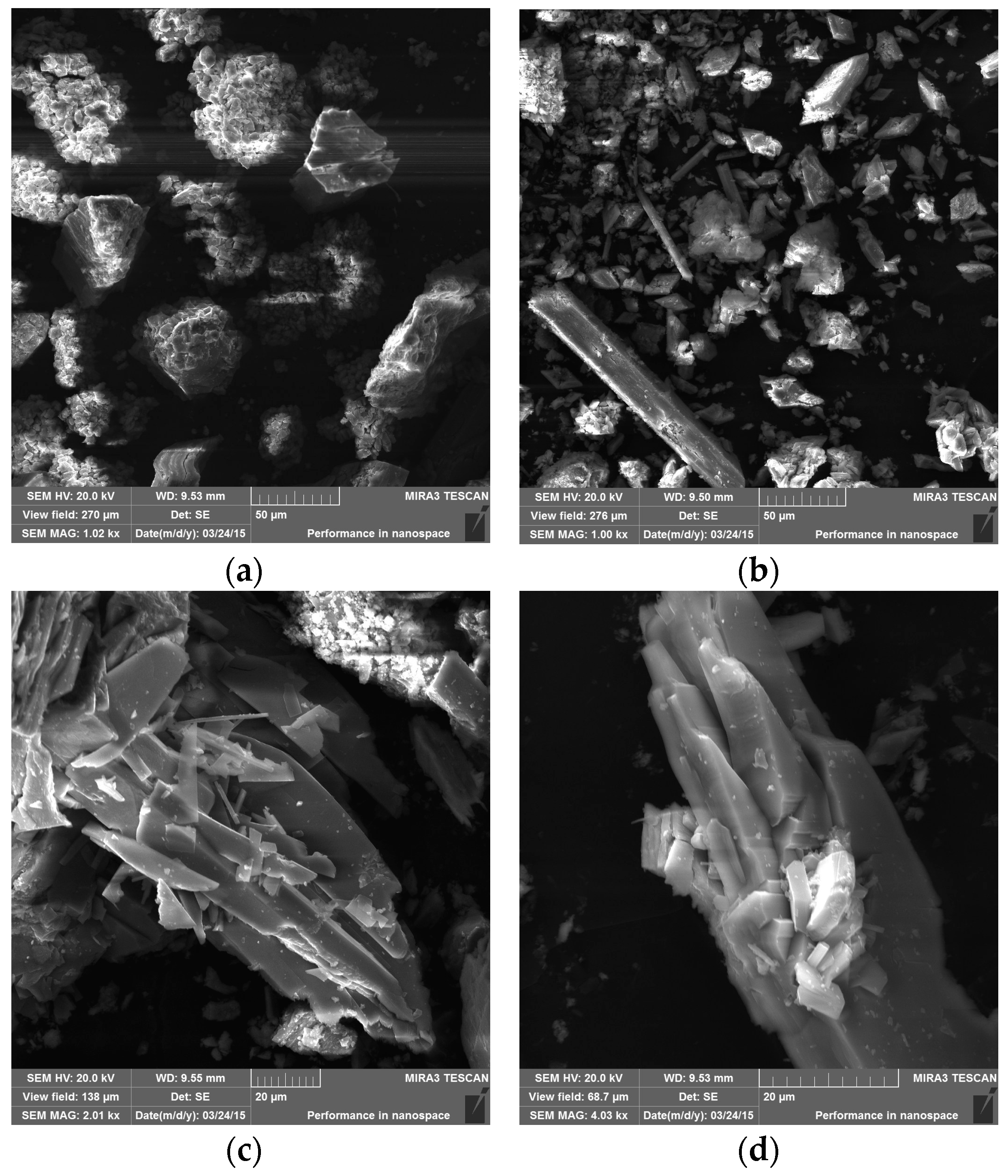

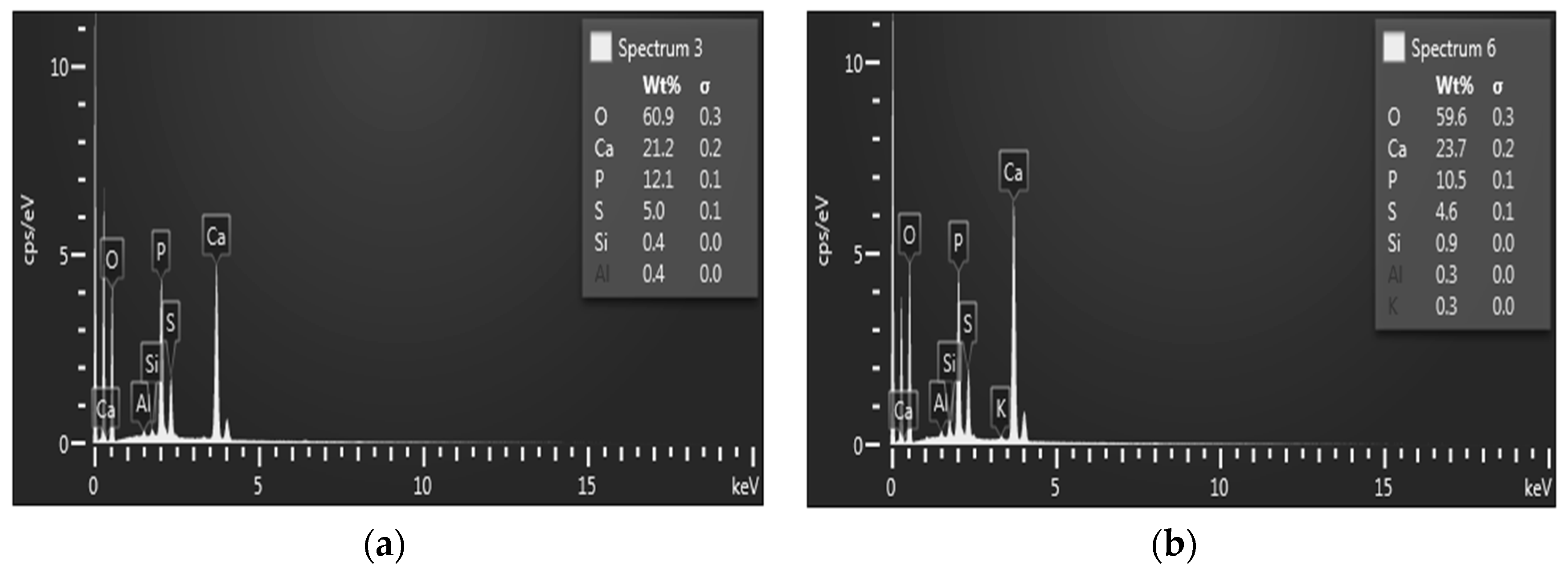

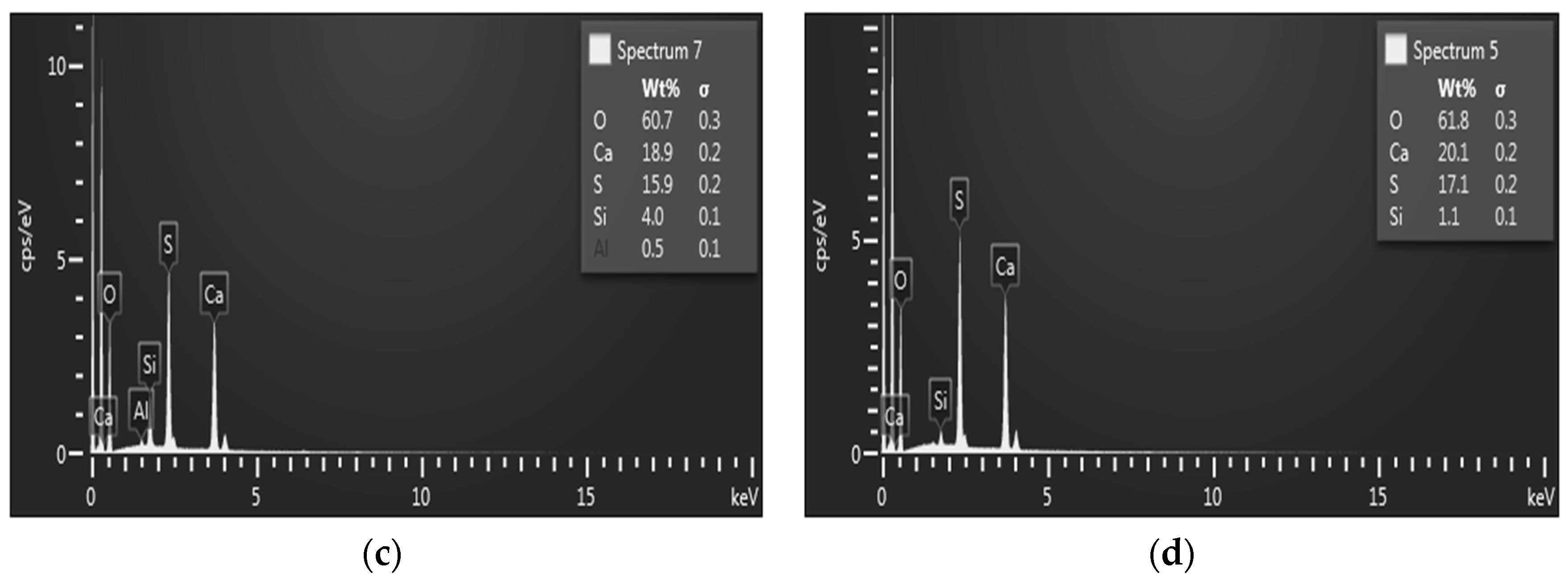

3.1. Cement and Silica Fume

3.2. Concrete Composite Samples

3.3. Chemical Corrosion Simulation

3.4. Microbial Corrosion Simulation

3.5. Analytical Methods

4. Conclusions

- Microbiological attack precipitated by Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans was more dangerous, in terms of leaching of the main components, than chemical sulfate attack with the exception of a H2SO4 solution of a pH of 3.

- The concrete samples equipped with silica fume exhibited better durability, in terms of the leaching of Si4+ and Ca2+, than concrete samples without silica fume.

- Significantly lower leachable fractions, specifically those 2.9- and 2.3-fold lower for Si4+ and Ca2+, respectively, were observed for silica fume-based samples exposed to H2SO4 with a pH of 3 compared with samples without silica fume.

- The calculated leachable fraction of Si4+ was 5.2- and 3.3-fold higher for samples without silica fume compared with the samples with silica fume under biological exposure.

- Silica fume concrete is not impervious to all aggressive chemicals. However, the study shows that at a low water to cement ratio (w/c), silica fume concrete can effectively prevent significant damage following many types of chemical attack including sewage leachate. Based on this finding, silica fume concrete has been specified for use in sewer and outfall pipes.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shinkafi, S.A.; Haruna, I. Microorganisms associated with deteriorated desurface painted concrete buildings within Sokoto, Nigeria. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, E. Construction Technology: An Illustrated Introduction; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005; p. 380. [Google Scholar]

- Little, B.J.; Lee, J.S. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B.; Cohen, M.D. Does gypsum formation during sulfate attack on concrete lead to expansion? Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann, F.; Stark, J. Prevention of thaumasite formation in concrete exposed to sulphate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann, K.Y.; Cho, C.H.G. Corrosion resistance of calcium aluminate cement concrete exposed to a chloride environment. Materials 2014, 7, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D. The effect of silica fume on the properties of concrete as defined in concrete society report 74. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures, Singapore, 29–31 August 2012.

- Wells, T.; Melchers, R.E. Modelling concrete deterioration in sewers using theory and field oservations. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 77, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, D.; Sanchez-Silva, M. Microbiologically induced deterioration of concrete—A review. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, T.; Melchers, R.E. An observation-based model for corrosion of concrete sewers under aggressive conditions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 61–62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwalina, B. Biodeterioration of concrete. ACEE 2008, 4, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.C.; Wang, K.; Xie, L. Deterioration mechanism of cementitious materials under acid rain attack. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 27, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M. Influence of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) on concrete durability. In Eco-Efficient Concrete; Pacheco-Torgal, F., Jalali, S., Labrincha, J., John, V.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A.; Chao, S.J.; Lin, W.T. Effects of leaching behavior of calcium ions on compression and durability of cement-based materials with mineral admixtures. Materials 2013, 6, 1851–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinicki, M.A.; Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D.; Gibas, K.; Dąbrowski, M. Influence of Blended Cements with Calcareous Fly Ash on Chloride Ion Migration and Carbonation Resistance of Concrete for Durable Structures. Materials 2016, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, K.; Kawamara, M. Effects of fly ash and silica fume on the resistance of mortar to sulfuric acid and sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 1994, 24, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senhadji, Y.; Escadeillas, G.; Mouli, M.; Khelafi, H.; Benosman, A.S. Influence of natural pozzolan, silica fume and limestone fine on strength, acid resistance and microstructure of mortar. Powder Technol. 2014, 254, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estokova, A.; Kovalcikova, M.; Luptakova, A. Deterioration of cement composites with silica fume addition due to chemical and biogenic corrosive processes. Solid State Phenom. 2015, 227, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nili, M.; Ehsanil, A. Investigating the effect of the cement paste and transition zone on strength development of concrete containing nanosilica and silica fume. Mater. Des. 2015, 75, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sokkary, T.M.; Assal, H.H.; Kandeel, A.M. Effect of silica fume or granulated slag on sulphate attack of ordinary Portland and alumina cement blend. Ceram. Int. 2004, 30, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małolepszy, J.; Grabowska, E. Sulphate attack resistance of cement with zeolite additive. Procedia Eng. 2015, 108, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, M.A.; Argiz, C.; Gálvez, J.C.; Moragues, A. Effect of silica fume fineness on the improvement of portland cement strength performance. Constructr. Build. Mater. 2015, 96, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraya, M.E.I. Study physico-chemical properties of blended cements containing fixed amount of silica fume, blast furnace slag, basalt and limestone, a comparative study. Constructr. Build. Mater. 2014, 72, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.A. Influence of silica fume, fly ash, super pozz, and high slag cement on water permeability and strength of concrete. Concr. Res. Lett. 2012, 3, 528–540. [Google Scholar]

- Suhendro, B. Toward green concrete for better sustainable environment. Procedia Eng. 2014, 95, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.; Moon, H.Y.; Swamy, R.N. Sulfate attack and role of silica fume in resisting strength loss. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, N.; Siddique, R.; Rajor, A. Influence of bacteria on the compressive strength, water absorption and rapid chloride permeability of concrete incorporating silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehdi, M.L.; Suleiman, A.R.; Soliman, A.M. investigation of concrete exposed to dual sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 64, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooss, M. Leaching of concrete under thermal influence. Otto Graf J. 2001, 12, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zelic, J.; Radovanovic, I.; Jozic, D. The effect of silica fume additions on the durability of Portland cement mortars exposed to magnesium sulfate attack. Mater. Technol. 2007, 41, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, P.; Sven, N.; Darimont, A. Influence of cement and aggregate type on thaumasite formation in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 53, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Nica, D.; Shields, K.; Roberts, D.J. Analysis of concrete from corroded sewer pipe. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1998, 42, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Otsuki, N.; Nishida, T.; Minagawa, H. Influence of type of cement on Ca leaching from concrete using experimental acceleration method. In Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures, Singapore, Singapore, 25–26 August 2004.

- Ganjian, E.; Pouya, H.S. Effect of magnesium and sulfate ions on durability of silica fume blended mixes exposed to the seawater tidal zone. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekal, E.E.; Kishar, E.; Mostafa, H. Magnesium sulfate attack on hardened blended cement pastes under different circumstances. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estokova, A.; Ondrejka Harbulakova, V.; Luptakova, A.; Prascakova, M.; Stevulova, N. Sulphur oxidizing bacteria as the causative factor of biocorrosion of concrete. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2011, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.; Lothenbach, B.; Scrivener, K.L.; Romer, M.; Rentsch, D.; Figi, R. A thermodynamic and experimental study of the conditions of thaumasite formation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization. EN 206–1: 2002 Concrete. Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. EN 12390–1: 2013 Testing Hardened Concrete. Part. 1: Shape, Dimensions and other Requirements for Specimens and Moulds; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. EN 12390–5: 2013 Testing Hardened Concrete. Part. 5: Flexural Strength of Test. Specimens; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karavajko, G.I.; Rossi, G.; Agate, A.D.; Groudev, S.N.; Avakyan, Z.A. Biogeotechnology of Metals: Manual; Centre for International Projects, GKNT: Moscow, Russia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| Mixture | Chemical Composition (wt %) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | SO3 | Cl | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 | Other | |

| M0 | 0.11 | 3.4 | 5.21 | 30.16 | 0.10 | 2.89 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 31.27 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 4.4 | 21.75 |

| M1 | 0.11 | 2.73 | 5.39 | 45.63 | 0.09 | 2.72 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 26.17 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 3.75 | 11.98 |

| Samples without SF (M0) | |||||||

| Element | Chemical Corrosion | Biological Corrosion | |||||

| M0-1 | M0-2 | M0-3 | M0-4 | M0-5 | M0-6 | M0-7 | |

| Vd max × 10−2 μg/(h × cm2) | |||||||

| Si | 6.410 | 1.466 | 1.259 | 0.949 | 4.906 | 10.537 | 5.486 |

| Ca | 16.942 | 0.677 | 2.759 | 1.584 | 1.044 | 5.906 | 3.134 |

| Samples with SF (M1) | |||||||

| Element | Chemical Corrosion | Biological Corrosion | |||||

| M1-1 | M1-2 | M1-3 | M1-4 | M1-5 | M1-6 | M1-7 | |

| Vd max × 10−2 μg/(h × cm2) | |||||||

| Si | 3.933 | 1.102 | 5.504 | 0.732 | 1.529 | 4.288 | 3.170 |

| Ca | 3.969 | 6.353 | 1.008 | 0.620 | 0.775 | 3.163 | 2.367 |

| Samples without SF (M0) | |||||||

| Element | Chemical Corrosion | Biological Corrosion | |||||

| M0-1 | M0-2 | M0-3 | M0-4 | M0-5 | M0-6 | M0-7 | |

| Si | 13.75 | 2.61 | 2.25 | 2.04 | 1.76 | 26.29 | 31.63 |

| Ca | 22.21 | 0.89 | 3.02 | 1.38 | 0.23 | 6.45 | 13.26 |

| Samples with SF (M1) | |||||||

| Element | Chemical Corrosion | Biological Corrosion | |||||

| M1-1 | M1-2 | M1-3 | M1-4 | M1-5 | M1-6 | M1-7 | |

| Si | 4.76 | 1.56 | 1.30 | 1.04 | 1.81 | 5.07 | 9.60 |

| Ca | 9.62 | 1.71 | 1.63 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 4.26 | 9.82 |

| Samples without SF (M0) | |||||||

| Mass (g) | Chemical Corrosion | Biological Corrosion | |||||

| M0-1 | M0-2 | M0-3 | M0-4 | M0-5 | M0-6 | M0-7 | |

| Before the experiment | 69.61 | 69.81 | 73.19 | 81.96 | 83.47 | 76.91 | 74.73 |

| After the experiment | 68.10 | 69.28 | 73.10 | 81.61 | 82.68 | 77.56 | 75.76 |

| Mass change (g) | 1.51 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.79 | −0.65 | −1.03 |

| Samples with SF (M1) | |||||||

| Mass (g) | Chemical Corrosion | Biological Corrosion | |||||

| M1-1 | M1-2 | M1-3 | M1-4 | M1-5 | M1-6 | M1-7 | |

| Before the experiment | 75.61 | 83.36 | 84.49 | 95.41 | 96.77 | 81.31 | 93.10 |

| After the experiment | 73.78 | 81.85 | 83.73 | 94.08 | 95.19 | 82.01 | 94.35 |

| Mass change (g) | 1.83 | 1.51 | 0.76 | 1.33 | 1.58 | −0.7 | −1.25 |

| Component | M0 | M1 |

|---|---|---|

| Cement (kg/m3) | 360 | 360 |

| Silica fume (kg/m3) | - | 20 |

| Natural aggregates, fraction 0/4 mm (kg/m3) | 825 | 750 |

| Natural aggregates, fraction 4/8 mm (kg/m3) | 235 | 235 |

| Natural aggregates, fraction 8/16 mm (kg/m3) | 740 | 740 |

| Water (L) | 170 | 191 |

| Polycarboxylate plasticizer (L) | 3.1 | 3.1 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estokova, A.; Kovalcikova, M.; Luptakova, A.; Prascakova, M. Testing Silica Fume-Based Concrete Composites under Chemical and Microbiological Sulfate Attacks. Materials 2016, 9, 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050324

Estokova A, Kovalcikova M, Luptakova A, Prascakova M. Testing Silica Fume-Based Concrete Composites under Chemical and Microbiological Sulfate Attacks. Materials. 2016; 9(5):324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050324

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstokova, Adriana, Martina Kovalcikova, Alena Luptakova, and Maria Prascakova. 2016. "Testing Silica Fume-Based Concrete Composites under Chemical and Microbiological Sulfate Attacks" Materials 9, no. 5: 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050324