Development of an Interview Guide Identifying the Rehabilitation Needs of Women from the Middle East Living with Chronic Pain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

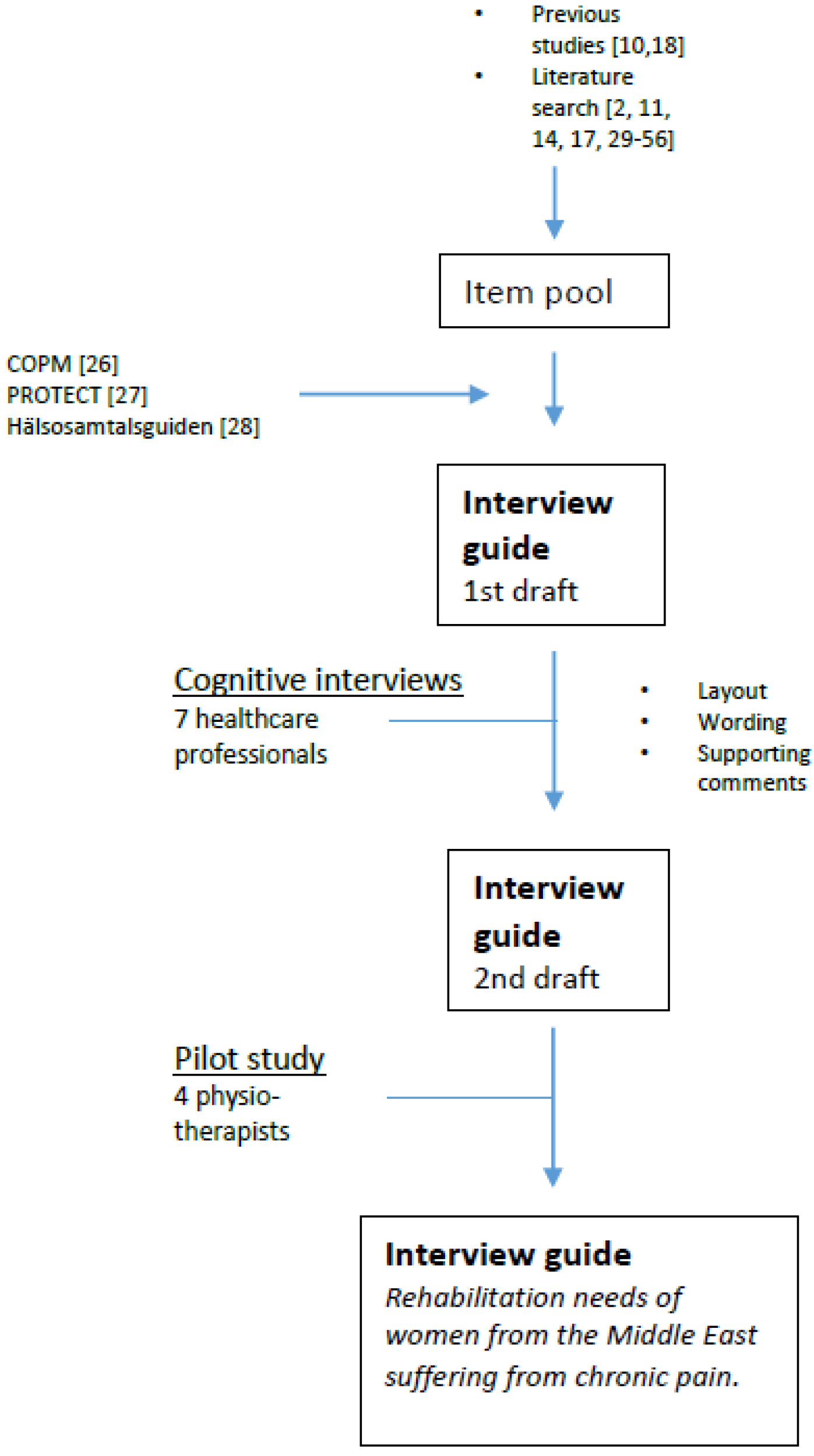

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Item Generation

3.2. Cognitive Interviews

3.3. Pilot Study

3.4. Construction of the Interview Guide

| Number | Item | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Does the patient need an interpreter? | [10,11,29,30,31,32,33,34] | |

| 2. | What are the patient’s reasons for seeking healthcare? | The patient’s narrative. Listen for 3 minutes for beliefs, concerns, and expectations. | [10,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] |

| 3. | The patient’s background? | Country of origin, family, previous occupation, reasons for migration, experienced trauma. | [10,11,17,18,28,39,47] |

| 4. | What medical assessments has the patient gone through in Sweden or another country? | The patient’s narrative. Compare with beliefs, concerns, and expectations. | [10,17,18,29,30,33,37,45] |

| 5. | What diagnoses has she received? | ||

| 6. | What treatments has she undergone? | ||

| 7. | What is the patient’s life situation in Sweden? | Living conditions, occupation, finances, social networks, satisfaction with her life. | [2,10,14,18,28,35,37,44,48,49,50,51] |

| 8. | Is there anything or anyone in the patient’s surroundings that impacts her wellbeing? | [10,14,28,35,37,52,53] | |

| 9. | Does the patient experience: Sleeping difficulties? Nightmares? Persistent headaches? Easily getting angry? Thoughts about painful past events? Feelings of fear? Memory difficulties? Trouble concentrating? | Yes or no. Positive answers indicate risk for patient being traumatized. | [11,14,17,27,33,44,54,55,56] |

| 10. | What plans does the patient have for her future? | [10,28] | |

| 11. | What does she need to do in order to fulfill her plans? | ||

| 12. | Experiences of difficulties in daily life? | Activities in everyday life, at work, leisure activities. | [10,17,26,39,56] |

| 13. | How does the patient manage everyday life? | Active, passive, spiritual, and emotional strategies. | [10,17,18,35,39,53] |

| 14. | Prioritized activities: 1. 2. 3. | Let the patient select three activities in her everyday life that she perceives as difficult to perform and that are important to her. | [26] |

| 15. | Performance of prioritized activities? | Estimate performance: Not able to perform Can partially perform Is able to perform | |

| 16. | How satisfied is the patient with her performance? | Estimate satisfaction with performance: Not satisfied at all Somewhat satisfied Fully satisfied |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Implications

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Sweden. Befolkningsstatistik (Demographics). Available online: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistik-efter-amne/Befolkning/Befolkningens-sammansattning/Befolkningsstatistik/#c_li_120253 (accessed on 3 September 2015).

- Daryani, A.; Löthberg, K.; Feldman, I.; Westerling, R. Different conditions—Different health. Health among Iraqis registered in Malmö 2005–2007. J. Soc. Med. 2012, 89, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hjern, A. Migration and public health: Health in Sweden: The National Public Health Report 2012. Chapter 13. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, J.A.; Wilson, K. “My health has improved because I always have everything I need here...”: A qualitative exploration of health improvement and decline among immigrants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laban, C.J.; Gernaat, H.B.P.E.; Komproe, I.H.; van der Tweel, I.; De Jong, J.T.V.M. Postmigration living problems and common psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2005, 193, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhavan, S.; Bildt, C.; Wamala, S. The health of female Iranian immigrants in Sweden: A qualitative six-year follow-up study. Health Care Women Int. 2007, 28, 339–359. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, H.; Farrag, M.; Hakim-Larson, J.; Kafaji, T.; Abdulkhaleq, H.; Hammad, A. Mental health symptoms in Iraqi refugees: Posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. J. Cult. Divers. 2007, 14, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jamil, H.; Nassar-McMillan, S.; Lambert, R.; Wangd, Y.; Ager, J.; Arnetz, B. Pre- and post-displacement stressors and time of migration as related to self-rated health among Iraqi immigrants and refugees in Southeast Michigan. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2010, 26, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindencrona, F.; Ekblad, S.; Hauff, E. Mental health of recently resettled refugees from the Middle East in Sweden: The impact of pre-resettlement trauma, resettlement stress and capacity to handle stress. Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid. 2008, 43, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, V.; Müllersdorf, M.; Christensson, K.; Eriksson, H. Struggling for sense of control: Everyday life with chronic pain for women of the Iraqi diaspora in Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2013, 41, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, S.S. Primary care management of non-English-speaking refugees who have experienced trauma: A clinical review. JAMA 2013, 310, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adanu, R.M.; Johnson, T.R. Migration and women’s health. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 106, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, K.F.; Resick, L.K. The description of health among Iraqi refugee women in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarasinghe, K.; Fridlund, B.; Arvidsson, B. Primary health care nurses’ conceptions of involuntarily migrated families’ health. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2006, 53, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, A.; White, M.; Posade, S.T.; Dillon, W. Using nominal group technique to assess chronic pain, patients’ perceived challenges and needs in a community health region. Health Expect. 2003, 6, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prefontaine, K.; Rochette, A. A literature review on chronic pain: The daily overcoming of a complex problem. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 76, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllersdorf, M.; Zander, V.; Eriksson, H. The magnitude of reciprocity in chronic pain management: Experiences of dispersed ethnic populations of Muslim women. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2011, 25, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, V.; Eriksson, H.; Christensson, K.; Müllersdorf, M. Rehabilitation of Women from the Middle East Living with Chronic Pain-Perceptions from Health Care Professionals. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07399332.2014.989439 (accessed on 16 December 2014).

- Lagerblad, A. Great Ignorance of the Consequences of Torture. Available online: http://www.svd.se/stor-okunskap-om-tortyrens-konsekvenser (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Lagerblad, A. Psychological Torture Sometimes Worse than Physical. Available online: http://www.svd.se/psykisk-tortyr-kan-vara-varre-an-fysisk (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Keyes, E.F. Mental health status in refugees: An integrative review of current research. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2000, 21, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R. Health Measurement Scales. A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ. Today 1991, 11, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J. Cognitive interviewing: Verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 42, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pett, M.A.; Lackey, N.R.; Sullivan, J.J. Designing and testing the instrument. In Making Sense of Factor Analysis; Pett, M.A., Lackey, N.R., Sullivan, J.J., Eds.; SAGE publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 13–49. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; McColl, M.; Opzoomer, A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 1990, 57, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Process of Recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment (PROTECT). Questionnaire and Observations for Early idenTification of Asylum Seekers Having Suffered Traumatic Experiences. Available online: http://www.parcours-exil.org/IMG/pdf/protect_project.pdf (accessed 24 October 2014).

- The Red Cross, Save the Children, Church of Sweden. Health Conversation Guide. Available online: www.redcross.se/PageFiles/3679/H%C3%A4lsosamtalsguiden-%20Vuxen.pdf (accessed 24 October 2014).

- Eckstein, B. Primary care for refugees. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 83, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harmsen, J.A.; Bernsen, R.M.; Bruijnzeels, M.A.; Meeuwesen, L. Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: What are the cultural and linguistic barriers? Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 72, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harpelund, L; Nielsen, S.S.; Krasnik, A. Self-perceived need for interpreter among immigrants in Denmark. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaric, N.; Bedford, S.; van Driel, M.L. Two sides of the coin: Patient and provider perceptions of health care delivery to patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Sandhu, S.; Dias, S.; Gaddini, A.; Greacen, T.; Ioannidis, E.; Kluge, U.; Krasnik, A.; Lamkaddem, M.; Lorant, V.; et al. Good practice in health care for migrants: Views and experiences of care professionals in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruppen, W.; Bandschapp, O.; Urwyler, A. Language difficulties in outpatients and their impact on a chronic pain unit in Northwest Switzerland. Swiss. Med. Wkly. 2010, 140, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bäärnhielm, S.; Ekblad, S. Turkish migrant women encountering health care in Stockholm: A qualitative study of somatization and illness meaning. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2000, 24, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäärnhielm, S.; Ekblad, S. Introducing a psychological agenda for understanding somatic symptoms—An area of conflict for clinicians in relation to patients in a multicultural community. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäärnhielm, S.; Håkansson, B.; Löfvander, M. 1171 Läkemedelsanvändning, Transkulturell medicin (Use of medication, Transcultural medicine). Läkemedelsboken: Apoteket AB, Sweden, 2009–2010. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Cortis, J.D. Caring as experienced by minority ethnic patients. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2000, 47, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, C.T.; Bensing, J.M.; de Ruijter, A. Worries are the mother of many diseases: General practitioners and refugees in the Netherlands on stress, being ill and prejudice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 65, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gard, G. Factors important for good interaction in physiotherapy treatment of persons who have undergone torture: A qualitative study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2007, 23, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, U.; Halder, C.; Litschi, M.; Sprott, H. Pain and psychological health status in chronic pain patients with migration background—the Zurich study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 32, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löfvander, M.B.; Engström, A.W.; Iglesias, E. Do dialogues about concepts of pain reduce immigrant patients’ reported spread of pain? A comparison between two consultation methods in primary care. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löfvander, M.; Dyhr, L. Transcultural general practice in Scandinavia. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2002, 20, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpinati Rosso, M.; Bäärnhielm, S. Use of the Cultural Formulation in Stockholm: A qualitative study of mental illness experience among migrants. Transcult. Psychiatry 2012, 49, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloots, M.; Scheppers, E.F.; Bartels, E.A.C.; Dekker, J.H.M.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Dekker, J. First rehabilitation consultation in patients of non-native origin: Factors that lead to tension in the patient-physician interaction. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 1853–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suurmond, J.; Uiters, E.; de Bruijne, M.C.; Stronks, K.; Essink-Bot, M.L. Negative health care experiences of immigrant patients: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löfvander, M. Transcultural general practice. J. Soc. Med. 2008, 5, 398–408. [Google Scholar]

- Löfvander, M.B.; Engstrom, A.W. The immigrant patient having widespread pain. Clinical findings by physicians in Swedish primary care. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löfvander, M.B.; Engström, A.W. “Unable and useless” or “able and useful”? A before and after study in the primary care of self-rated inability to work in young immigrants having long-standing pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2004, 17, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.D.; Popper, S.T.; Rodwell, T.C.; Brodine, S.K.; Brouwer, K.C. Healthcare barriers of refugees post-resettlement. J. Commun. Health 2009, 34, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, M.F.; Falk, L.; Bjorn, A.; Wilhelmsson, S. Experiences of the Swedish healthcare system: an interview study with refugees in need of long-term health care. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, S. Psychosocial aspects of chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturkenboom, I.; Dekker, J.; Scheppers, E.; van Dongen, E. Healing care? Rehabilitation of female immigrant patients with chronic pain from a family perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebschutz, J.; Saitz, R.; Brower, V.; Keane, T.M.; Lloyd-Travaglini, C.; Averbuch, T.; Samet, J.H. PTSD in urban primary care: High prevalence and low physician recognition. J. Gen. Inter. Med. 2007, 22, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söndergaard, H.P.; Ekblad, S.; Theorell, T. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder among refugees in Stockholm. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2003, 57, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.; Carswell, K.; Williams, A.C. The interaction of persistent pain and post-traumatic re-experiencing: A qualitative study in torture survivors. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 46, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, I.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A.; Brink, E.; Carlsson, J.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Johansson, I.L.; Kjellgren, K.; et al. Person-centered care—Ready for prime time. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nur. 2011, 10, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skuladottir, H.; Halldorsdottir, S. The quest for well-being: Self-identified needs of women in chronic pain. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2011, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, D.; Dwinnell, B.; Platt, F. Invite, listen, and summarize: A patient-centered communication technique. Acad. Med. 2005, 80, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zander, V.; Eriksson, H.; Christensson, K.; Müllersdorf, M. Development of an Interview Guide Identifying the Rehabilitation Needs of Women from the Middle East Living with Chronic Pain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 12043-12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121012043

Zander V, Eriksson H, Christensson K, Müllersdorf M. Development of an Interview Guide Identifying the Rehabilitation Needs of Women from the Middle East Living with Chronic Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(10):12043-12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121012043

Chicago/Turabian StyleZander, Viktoria, Henrik Eriksson, Kyllike Christensson, and Maria Müllersdorf. 2015. "Development of an Interview Guide Identifying the Rehabilitation Needs of Women from the Middle East Living with Chronic Pain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 10: 12043-12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121012043

APA StyleZander, V., Eriksson, H., Christensson, K., & Müllersdorf, M. (2015). Development of an Interview Guide Identifying the Rehabilitation Needs of Women from the Middle East Living with Chronic Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(10), 12043-12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121012043