Refugees Connecting with a New Country through Community Food Gardening

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

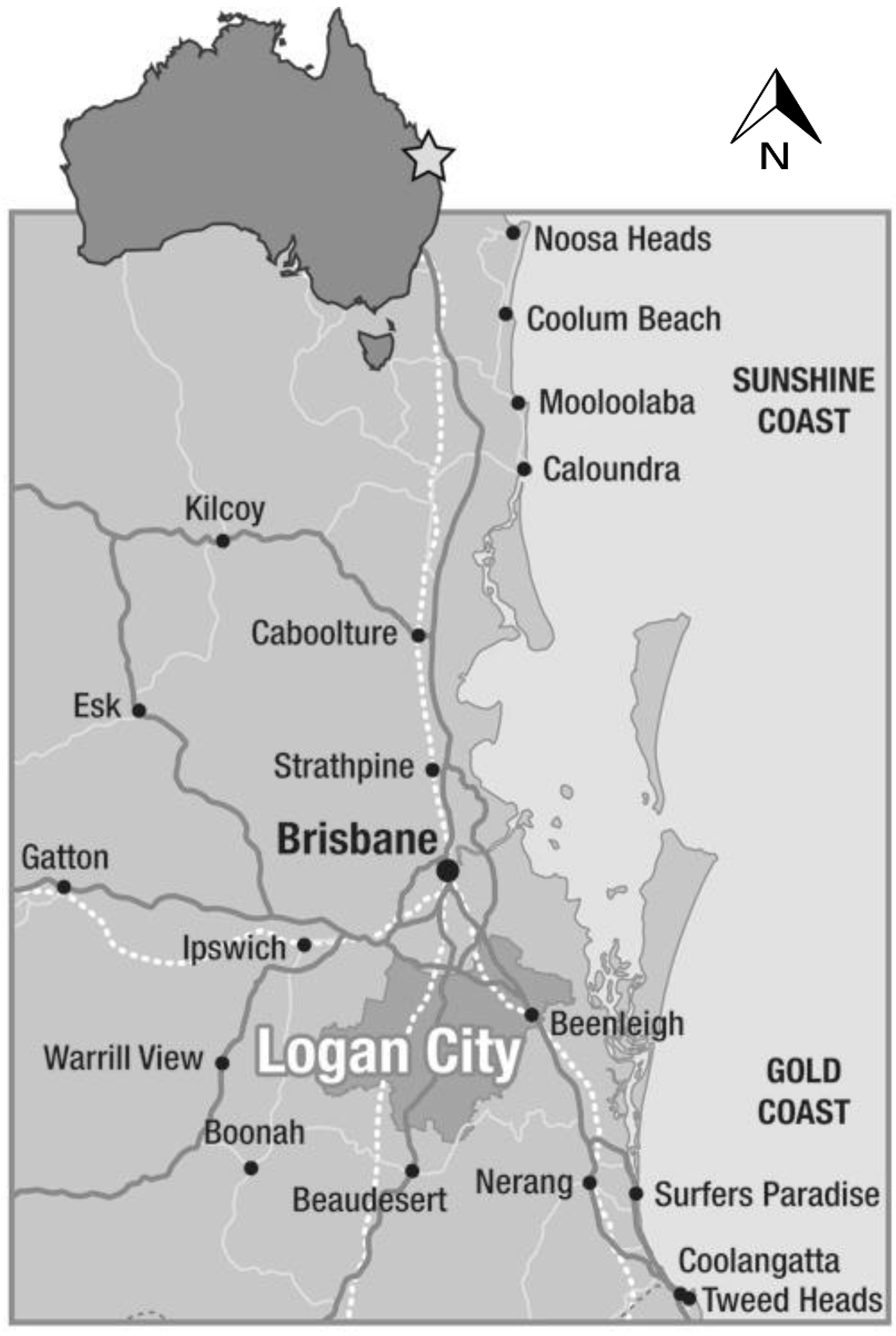

2.1. Study Setting and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- Why did you join the garden?

- Why do you come to the garden?

- Why is being part of the garden important for you?

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theme 1: Land Tenure

In Africa it is the citizens who have gardens. The foreigners do not have gardens. Now I have a garden, I feel like a citizen.(Gardener F)

When she digs her own farm and grows the way she knows, then she will eat what she knows.(Gardener B).

He is relieved to have a land here to dig. He believes it was very important for an African person, if they didn’t go to school, which majority didn’t, they had to be a farmer. So the closeness was very good, the bond between the human and the soil was of great importance. … This is the only place here for him to dig so that is why it is important for him.(Gardener D).

3.2. Theme 2: Re-Connecting with Agri-Culture

Both my parents were farmers. It’s knowledge and skills passed down through the generations. I have just been given a plot and am doing everything according to my knowledge and talent basically. I plant them the way I know.(Gardener B)

Remember when the maize grew, that was huge. That was amazing, it was like we had all this stuff.(Gardener G)

If you’re a farmer, it covers the whole part of your life, in terms of exercising and in terms of your whole wellbeing. It is very important for me to be in the garden for my whole total wellbeing.(Gardener E)

3.3. Theme 3: Community Belonging

She says when the produce are good it makes her happy because everything is good and she can share with other people. She relates better with people when she has good products and good produce. She feels good about it.(Gardener B)

Like last year, I grow maize and peanut in the garden and cassava, so I give it to my friends. It’s a good thing to give it because if I have something they need I can give and if they have something I need, they can give to me also.(Gardener A)

It brings a lot of, not only satisfaction but relief, sense of belonging and you feel people understand you, you feel people… you’re part of that community that you’re in.(Gardener A)

In the garden there, we work together, yeah .Get things done. Is good because we need to know each other and work together or things won’t finish.(Gardener D)

3.4. Broader Significance of Findings

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Popkin, B.M. Dynamics of the nutrition transition and its implications for the developing world. Forum Nutr. 2003, 56, 262–264. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A.; Ganda, O.P. Migration and its impact on adiposity and type 2 diabetes. Nutrition 2007, 23, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, N.; Kennedy, S.; McDonald, J.T. Health assimilation patterns amongst Australian immigrants. Econ. Rec. 2007, 83, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevoyan, A.; Hugo, G. Exploring Migrant Health in Australia. In Proceedings of the IUSSP XXVII International Population Conference, Busan, Korea, 26–31 August 2013.

- Murray, S.B.; Skull, S.A. Hurdles to health: Immigrant and refugee health care in Australia. Aust. Health Rev. 2004, 29, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. Primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers: A review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Health 2006, 120, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffla, C. Health in the age of migration: Migration and health in the EU. Community Pract. 2008, 81, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tiong, A.C.D.; Patel, M.S.; Gardiner, J.; Ryan, R.; Linton, K.S.; Walker, K.A.; Scopel, J.; Biggs, B.-A. Health Issues in newly arrived African refugees attending general practice clinics in Melbourne. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- NSW Health. Refugees from Africa. Available online: http://www.swslhd.nsw.gov.au/refugee/pdf/Resource/FactSheet/FactSheet_06.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Refugee Week. Background Information on Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Available online: http://www.refugeeweek.org.au/resources/background.php (accessed on 30 July 2014).

- Jakubowicz, A. Australia’s Migration Policies: African Dimensions. Available online: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/africanaus/papers/africanaus_paper_jakubowicz.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2014).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3412.0—Migration, Australia, 2009–2010. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/0/52F24D6A97BC0A67CA2578B0001197B8?opendocument (accessed on 30 July 2014).

- Hart, E.W. Settlement Geography of African Refugee Communities in Southeast Queensland: An Analysis of Residential Distribution and Secondary Migration. Available online: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/38622/1/Elizabeth_Harte_Thesis.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2014).

- Sheikh-Mohammed, M.; Macintyre, C.R.; Wood, N.J.; Leask, J.; Isaacs, D. Barriers to access to health care for newly resettled sub-Saharan refugees in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 594–597. [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho, A.M.; Gibbons, C.; Swinburn, B.; Jolley, D.; Burns, C. Obesity and undernutrition in Sub-Saharan African immigrant and refugee children in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 15, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hadley, C.; Sellen, S. Food security and child hunger among recently resettled Liberian refugees and asylum seekers: A pilot study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2006, 8, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, C. Effect of migration on food habits of Somali women living as refugees in Australia. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2004, 43, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, N.T.; Green, N.R. Food habits and food preferences of Vietnamese refugees living in northern Florida. J. Amer. Diet. Assn. 1980, 76, 591–593. [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho, A.M. Post-Migration food habits of Sub-Saharan African. Nutr. Diet. 2006, 63, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S.M.; Hancock, B. “Reaching the hard to reach”—Lessons learned from the VCS (Voluntary and Community Sector). A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, D. A survey of community gardens in upstate New York: Implications for health promotion and community development. Health Place 2000, 6, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baker, L.E. Tending cultural landscapes and food citizenship in Toronto’s community gardens. Geogr. Rev. 2004, 94, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.S. Empowerment and community building through a gardening project. Psychiatr. Rehabilitat. J. 1998, 22, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S.; Yeudall, F.; Taron, C.; Reynolds, J.; Skinner, A. Growing urban health: Community gardening in south-east Toronto. Health Promot. Int. 2007, 22, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferris, J.; Norman, C.; Sempik, J. People, land and sustainability: Community gardens and the social dimension of sustainable development. Soc. Policy Admin. 2001, 35, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, M.W.; Baron, M. Developing an integrated, sustainable urban food system: The case of New Jersey, United States. In For Hunger-Proof Cities Sustainable Urban Food Systems; Koc, M., MacRae, R., Mougeot, L.J.A., Welsh, J., Eds.; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P. Reweaving the food security safety net: Mediating entitlement and entrepreneurship. Agric. Human Values 1999, 16, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.N.; Johnston, Y.A.; Morgan, L.L. Community gardening in a senior center: A therapeutic intervention to improve the health of older adults. Ther. Recreat. J. 2006, 40, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzkopf, K. Urban community gardens as contested space. Geogr. Rev. 1996, 85, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.L. Basics of Social Research. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case study research. In Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.L.; Bennett, A. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences; MIT Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Government, Queensland Treasury and Trade. Queensland Regional Profiles: Resident Profile for Logan City Local Government Area. Available online: http://statistics.oesr.qld.gov.au/qld-regional-profiles (accessed on 30 June 2014).

- Logan City Council. Logan City Cultural Diversity Strategy 2013–2016. Available online: http://www.logan.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/111104/Cultural-Diversity-Strategy-2013–2016-Draft-for-Public-Consultation.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2014).

- Logan City Council. Living in Logan: Maps. Available online: http://www.logan.qld.gov.au/about-logan/living-in-logan/maps (accessed on 10 August 2014).

- Liamputtong, P.; Ezzy, D. Qualitative Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, J.; Eyles, J. Evaluating qualitative research in social geography: Establishing “rigour” in interview analysis. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1997, 22, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, B.M.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, I.; Dossa, P. Place, health and home: Gender and migration in the constitution of healthy space. Health Place 2007, 13, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, R.; Gifford, S.M. Place-making, settlement and well-being: The therapeutic landscapes of recently arrived youth with refugee backgrounds. Health Place 2010, 16, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.W.; Hodgetts, D.; Ho, E. Gardens, transitions and identity reconstruction among older Chinese immigrants to New Zealand. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, A.; James, W. War in the former Yugoslavia: Coping with nutritional issues. In Essentials of Human Nutrition; Mann, J.I., Truswell, A.S.T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 557–574. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model. Promot. Educ. 2007, 2, S17–S22. [Google Scholar]

- ACT Government, Environment and Planning. A Study of the Demand for Community Gardens and Their Benefits for the ACT Community. Available online: http://www.actpla.act.gov.au/tools_resources/research_based_planning_for_a_better_city/demand_for_community_gardens_and_their_benefits (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Christensen, P. Farming the city. Local-Glob. Identity Secur. Community 2007, 4, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jordans, M.; Tol, W.; Kimproe, I.; Jong, D.J. Systematic review of evidence and treatment approaches: Psychosocial and mental health care for children in war. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2009, 14, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.D.; Bearman, P.S.; Blum, R.W.; Bauman, K.E.; Harris, K.M.; Jones, J.; Tabor, J.; Beuhring, T.; Sieving, R.E.; Shew, M.; et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. JAMA 1997, 278, 823–832. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health: From observation to policy. Med. J. Aust. 2000, 172, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Onyx, J.; Leonard, R. The conversion of social capital into community development: An intervention in Australia’s outback. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.; Harris, N. Understanding the nutrition information needs of migrant communities: The needs of African and Pacific Islander communities of Logan, Queensland. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timperio, A.; Ball, K.; Roberts, R.; Campbell, K.; Andrianopoulos, N.; Crawford, D. Children’s fruit and vegetable intake: Associations with the neighbourhood food environment. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.V.; Roux, A.V.D.; Brines, S. Comparing perception-based and geographic information system (GIS)-based characterizations of the local food environment. J. Urban Health. 2008, 85, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.I.; Story, M.T.; Nelson, M.C. Neighbourhood environments: Disparities in access to healthy food in the U.S. Amer. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.C.; Cutumisu, N.; Edwards, J.; Raine, K.D.; Smoyer-Tomic, K. Relation between local food environments and obesity among adults. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D.; Richards, R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants of the U.S. food stamp program. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Grondin, D. Well-managed migrants’ health benefits all. Bull. WHO. 2004, 82. Available online: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/82/8/editorial20804html/en/ (accessed on 25 August 2014).

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J. Mapping the evolution of “food deserts” in a Canadian city: Supermarket accessibility in London, Ontario, 1961–2005. Int. J. Health Demogr. 2008, 7, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulac, J.; Kristjansson, E.; Cummins, S. A systematic review of food deserts, 1966–2007. In Prev. Chronic Dis.; 2009; 6. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2009/jul/08_0163.htm (accessed on 25 August 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bodor, J.N.; Rose, D.; Farley, T.A.; Swalm, C.; Scott, S.K. Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: The role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 11, 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Muecke, M.A. New paradigms for refugee health problems. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 35, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gushulak, B.D.; MacPherson, D.W. The basic principles of migration health: Population mobility and gaps in disease prevalence. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2006, 3, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerset, S.; Ball, R.; Flett, M.; Geissman, R. School-based community gardens: Re-establishing healthy relationships with food. J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust. 2005, 12, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Somerset, S.; Markwell, K. Impact of a school-based food garden on attitudes and identification skills regarding vegetables and fruit: A 12-month intervention trial. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 12, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldivar-Tanaka, L.; Krasny, M.E. Culturing community development, neighbourhood open-space, and civic agriculture: The case of Latino community gardens in New York city. Agric. Hum. Values 2004, 21, 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, D.; Rowe, F.; Harris, N.; Somerset, S. Quality of Life and Community Gardens: African Refugees and the Griffith University Community Food Garden. In Proceedings of Population Health Congress, Brisbane, Australia, 6–9 July 2008; p. 11.

- Wills, J.; Chinemana, F.; Rudolph, M. Growing or connecting? An urban food garden in Johannesburg. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsley, J.Y.; Townsend, M. “Dig In” to social capital: Community gardens as mechanisms for growing urban social connectedness. Urban Policy Res. 2006, 24, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Harris, N.; Minniss, F.R.; Somerset, S. Refugees Connecting with a New Country through Community Food Gardening. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9202-9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110909202

Harris N, Minniss FR, Somerset S. Refugees Connecting with a New Country through Community Food Gardening. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(9):9202-9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110909202

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarris, Neil, Fiona Rowe Minniss, and Shawn Somerset. 2014. "Refugees Connecting with a New Country through Community Food Gardening" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 9: 9202-9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110909202