The Ecology of Gynecological Care for Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Study Design

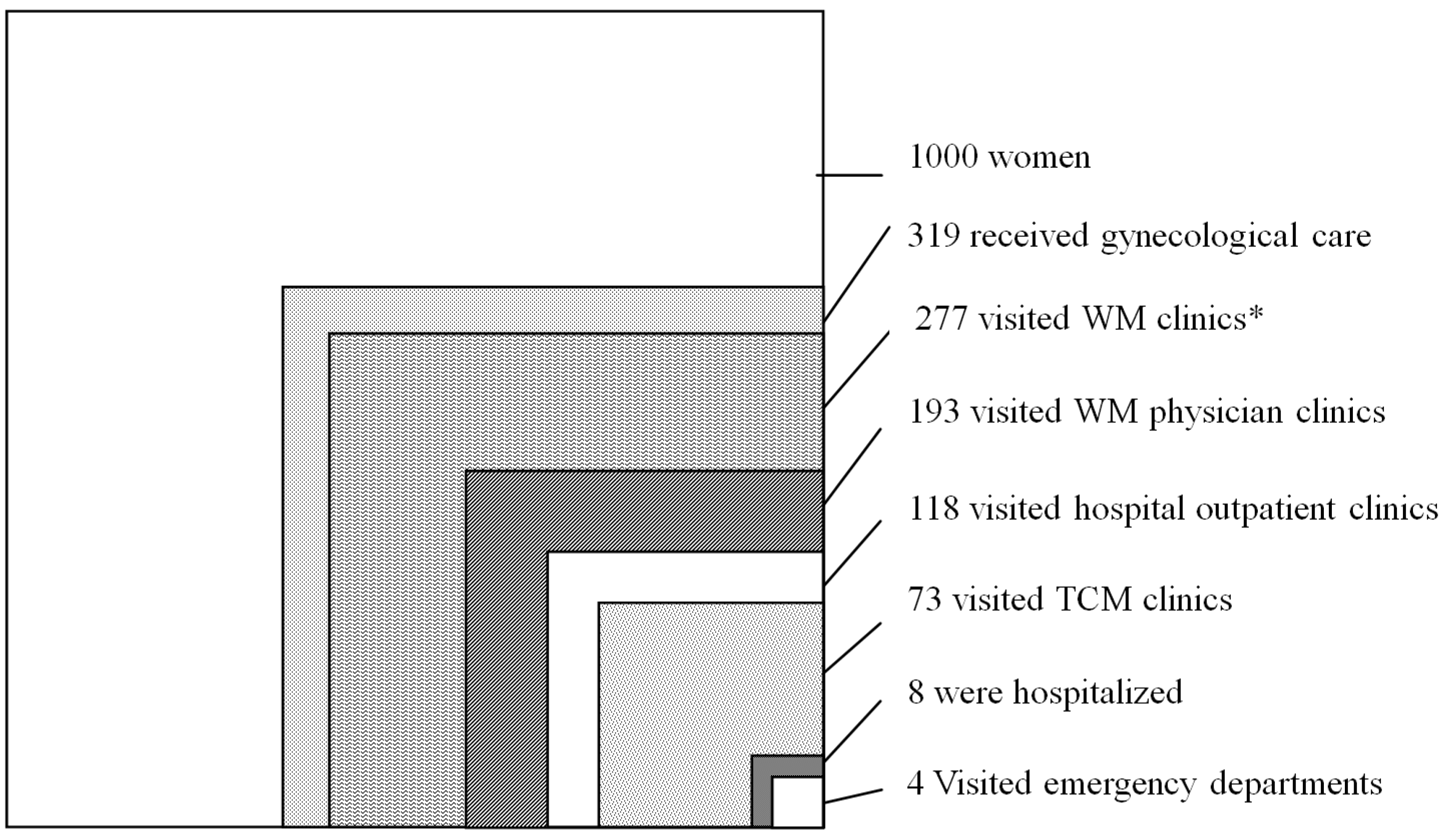

- Gynecological care utilization: How many women utilized gynecological care within NHI at least once?

- Visits to Western medicine (WM) clinics: How many women visited either physician clinics or hospital outpatient clinics?

- Visits to physician clinics (WM): How many women visited physician clinics?

- Visits to hospital outpatient clinics (WM): How many women visited outpatient clinics in any hospital?

- Visits to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) clinics: How many women visited physicians of traditional Chinese medicine, either in TCM physician clinics or at outpatient clinics?

- Visits to emergency departments (ED): How many women visited emergency departments?

- Admissions to wards in the hospitals: How many women were admitted to wards in any hospital?

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

| Category | Number of Women | Received GYN Care | Visits to WM Clinics | Visits to Physician Clinics (WM) | Visits to Hospital Outpatient Clinics (WM) | Visits to TCM Clinics | ED Visits | Hospitalizations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | LCH | MH | AMC | Any | LCH | MH | AMC | |||||||

| Number of Women/1000 Women | ||||||||||||||

| Overall Age | 1000 | 319.3 | 277.2 | 192.9 | 117.8 | 49.3 | 45.6 | 31.8 | 72.9 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

| 18–39 | 427 | 169.7 | 144.7 | 109.8 | 54.5 | 27.7 | 19.4 | 11.7 | 47.9 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 40–64 | 427 | 135.2 | 119.8 | 77.0 | 55.9 | 19.5 | 23.0 | 17.6 | 24.6 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| ≥65 | 146 | 14.4 | 12.6 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Category | Head Count | Visits to WM Clinics | Physician Clinics (WM) | Hospital Outpatient Clinics (WM) | Hospitalizations | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCH | MH | AMC | All | LCH | MH | AMC | |||||||||||||

| Number of Women/1000 Women | |||||||||||||||||||

| Provider specialty | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | GYN | Non-GYN | |

| Overall Age | 1000 | 264.8 | 23.7 | 182.3 | 15.8 | 47.7 | 2.3 | 43.7 | 3.0 | 30.1 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.5 |

| 18–39 | 427 | 142.1 | 6.4 | 107.3 | 4.8 | 27.3 | 0.5 | 19.0 | 0.6 | 11.4 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| 40–64 | 427 | 112.5 | 13.8 | 70.5 | 9.2 | 18.6 | 1.3 | 22.1 | 1.7 | 16.5 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.3 |

| ≥65 | 146 | 10.1 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

3.2. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicholson, W.K.; Ellison, S.A.; Grason, H.; Powe, N.R. Patterns of ambulatory care use for gynecologic conditions: A national study. Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 184, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.M.; Hillis, S.D.; Kieke, B.A., Jr.; Brett, K.M.; Marchbanks, P.A.; Peterson, H.B. Visits to emergency departments for gynecologic disorders in the United States, 1992–1994. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 91, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteman, M.K.; Kuklina, E.; Jamieson, D.J.; Hillis, S.D.; Marchbanks, P.A. Inpatient hospitalization for gynecologic disorders in the United States. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.L.; Williams, T.F.; Greenberg, B.G. The ecology of medical care. N. Engl. J. Med. 1961, 265, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L.A.; Fryer, G.E.; Yawn, B.P.; Lanier, D.; Dovey, S.M. The ecology of medical care revisited. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, T.; Rhaman, M.; Takahashi, O.; Saito, M.; Shimbo, T.; Endo, H.; Misao, H.; Fukuhara, S.; Hinohara, S. The ecology of medical care in Japan. Jpn. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 48, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G.M.; Wong, I.O.; Chan, W.S.; Choi, S.; Lo, S.V.; Health Care Financing Study Group. The ecology of health care in Hong Kong. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.C.; Chang, C.P.; Chou, L.F.; Chen, T.J.; Hwang, S.J. The ecology of medical care in Taiwan. JCMA 2011, 74, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dovey, S.; Weitzman, M.; Fryer, G.; Green, L.; Yawn, B.; Lanier, D.; Phillips, R. The ecology of medical care for children in the United States. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yawn, B.P.; Fryer, G.E.; Phillips, R.L.; Dovey, S.M.; Lanier, D.; Green, L.A. Using the ecology model to describe the impact of asthma on patterns of health care. BMC Pulm. Med. 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chou, L.F. The ecology of mental health care in Taiwan. Admin. Policy Mental Health 2006, 33, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.A.; Fryer, G.E.; Dovey, S.M.; Phillips, R.L. The contemporary ecology of U.S. Medical care confirms the importance of primary care. Amer. Fam. Physician 2001, 64, 928. [Google Scholar]

- McWhinney, I.R.; Freeman, T. Textbook of Family Medicine, 3rd ed.; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zollman, C.; Vickers, A. ABC of complementary medicine. Users and practitioners of complementary medicine. BMJ 1999, 319, 836–838. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.P.; Chen, T.J.; Kung, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Chou, L.F.; Chen, F.J.; Hwang, S.J. Use frequency of traditional chinese medicine in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary-Guida, M.B.; Okvat, H.A.; Oz, M.C.; Ting, W. A regional survey of health insurance coverage for complementary and alternative medicine: Current status and future ramifications. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2001, 7, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Perl Programming Language. Available online: http://www.perl.org/ (accessed on 11 April 2014).

- Bartman, B.A.; Weiss, K.B. Women’s primary care in the United States: A study of practice variation among physician specialties. J. Womens Health 1993, 2, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittdiel, J.; Selby, J.V.; Grumbach, K.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr. Women’s provider preferences for basic gynecology care in a large health maintenance organization. J. Womens Health Gend. Based Med. 1999, 8, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.J.; Chou, L.F.; Hwang, S.J. Patterns of ambulatory care utilization in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. Available online: http://www.hpa.gov.tw/English/ClassShow.aspx?No=201312110001 (accessed on 11 April 2014).

- Ozalp, S.; Tanir, H.M.; Gurer, H. Gynecologic problems among elderly women in comparison with women aged between 45–64 years. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2006, 27, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kjerulff, K.H.; Erickson, B.A.; Langenberg, P.W. Chronic gynecological conditions reported by us women: Findings from the national health interview survey, 1984 to 1992. Am. J. Public Health 1996, 86, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjerulff, K.H.; Frick, K.D.; Rhoades, J.A.; Hollenbeak, C.S. The cost of being a woman: A national study of health care utilization and expenditures for female-specific conditions. Womens Health Issues 2007, 17, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, C.-P.; Chou, C.-L.; Chou, Y.-C.; Shao, C.-C.; Su, H.I.; Chen, T.-J.; Chou, L.-F.; Yu, H.-C. The Ecology of Gynecological Care for Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7669-7677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110807669

Chang C-P, Chou C-L, Chou Y-C, Shao C-C, Su HI, Chen T-J, Chou L-F, Yu H-C. The Ecology of Gynecological Care for Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(8):7669-7677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110807669

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Chia-Pei, Chia-Lin Chou, Yueh-Ching Chou, Chun-Chih Shao, H. Irene Su, Tzeng-Ji Chen, Li-Fang Chou, and Hann-Chin Yu. 2014. "The Ecology of Gynecological Care for Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 8: 7669-7677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110807669