Cyclic Marinopyrrole Derivatives as Disruptors of Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL Binding to Bim

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Design of Marinopyrrole Derivatives

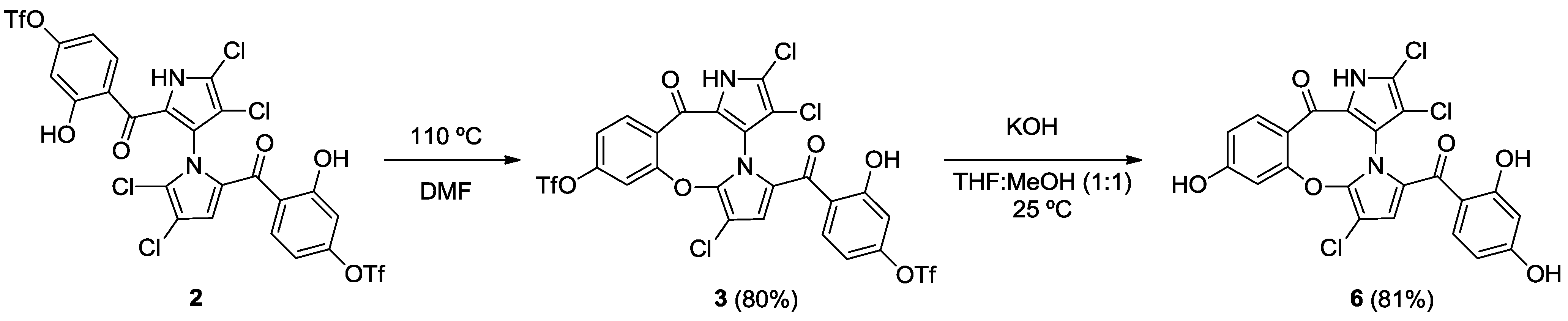

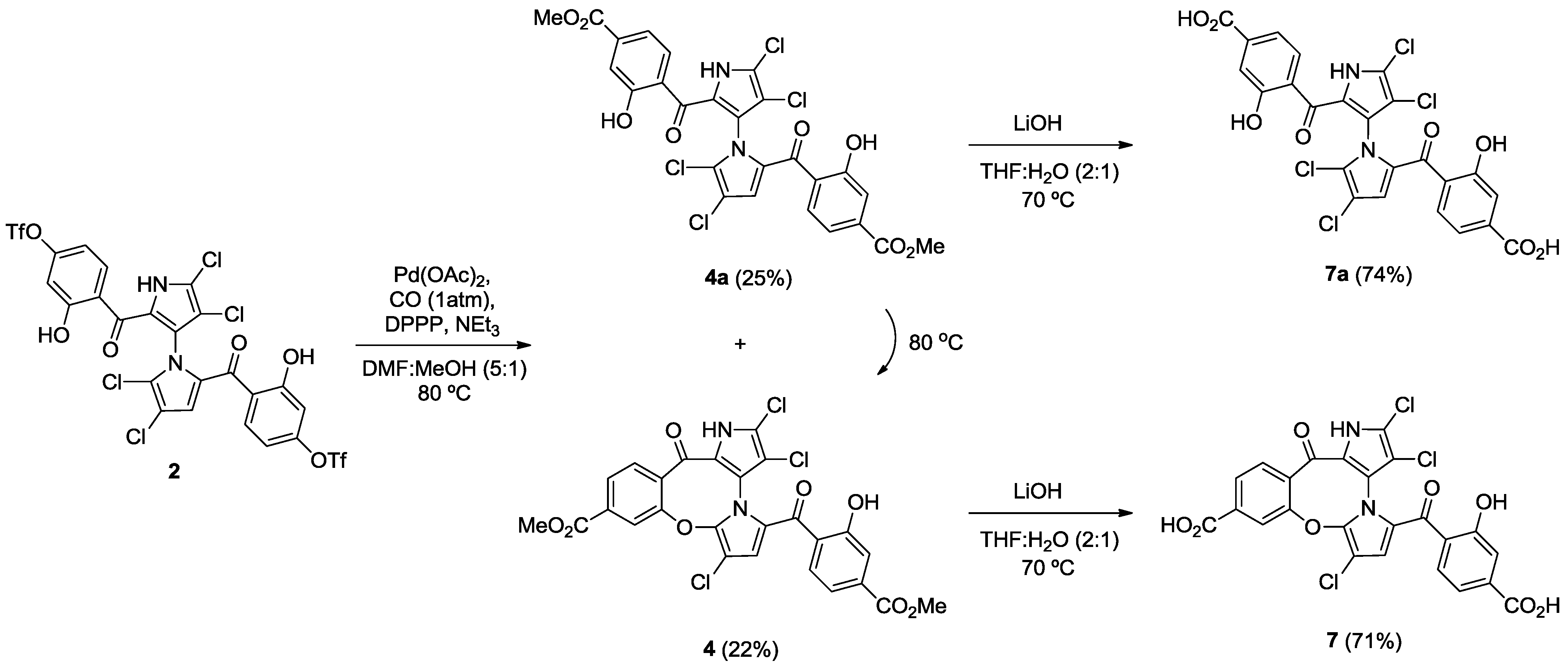

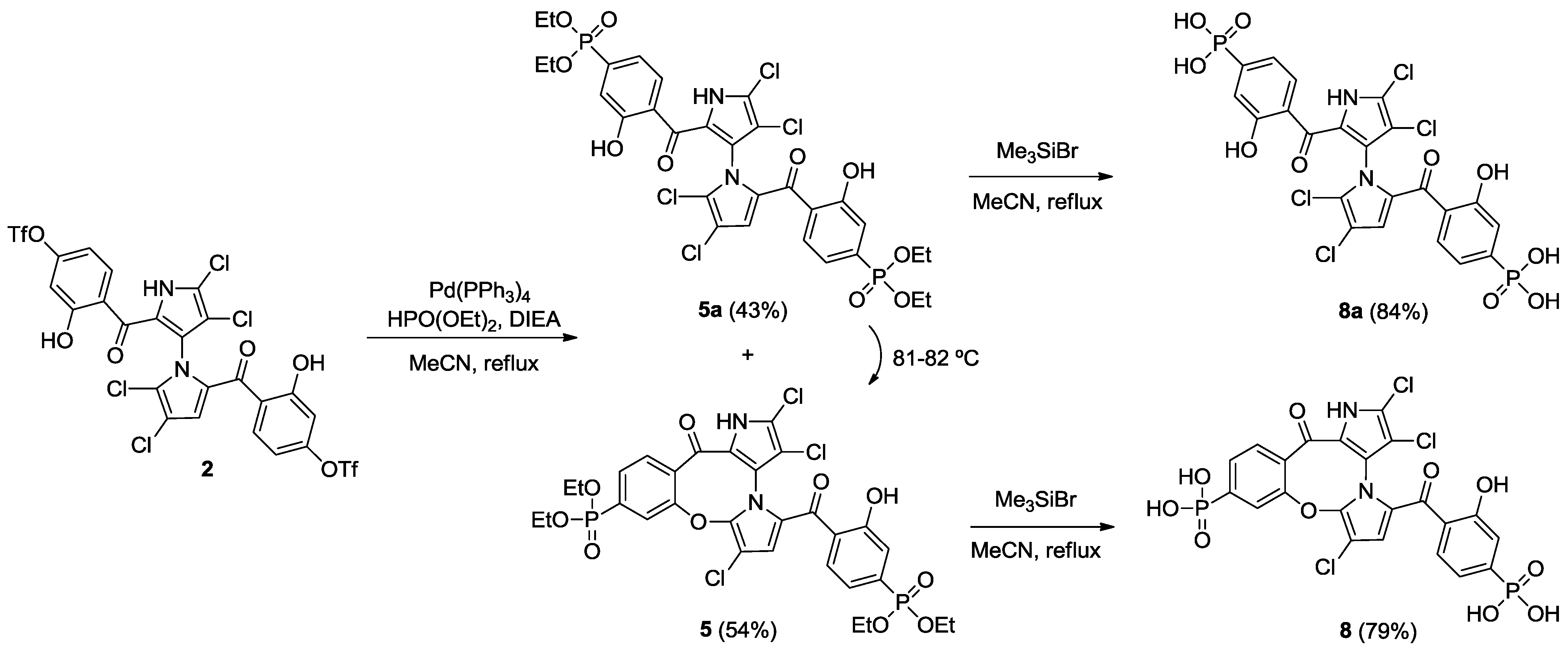

2.2. Synthesis of Marinopyrrole Derivatives

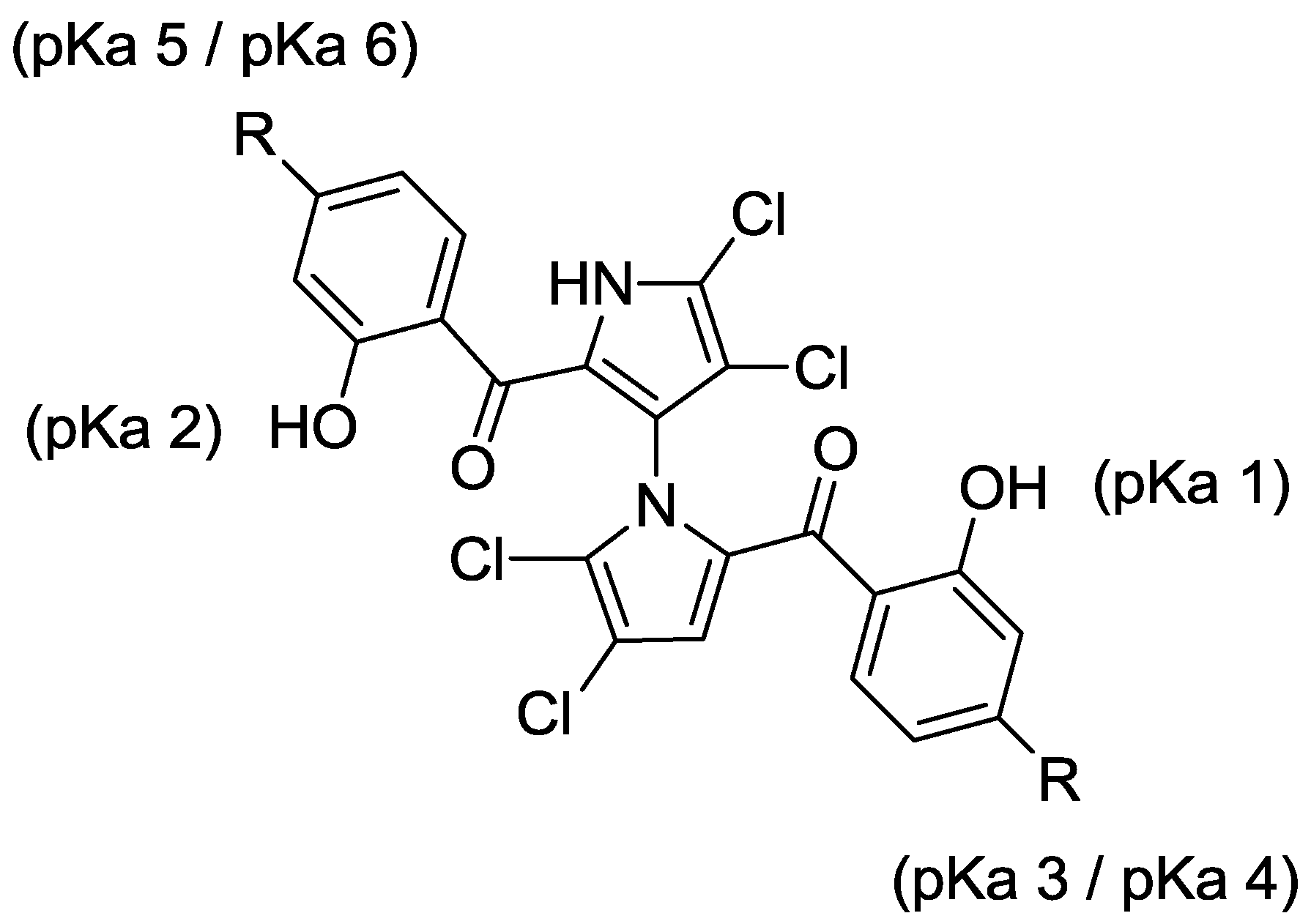

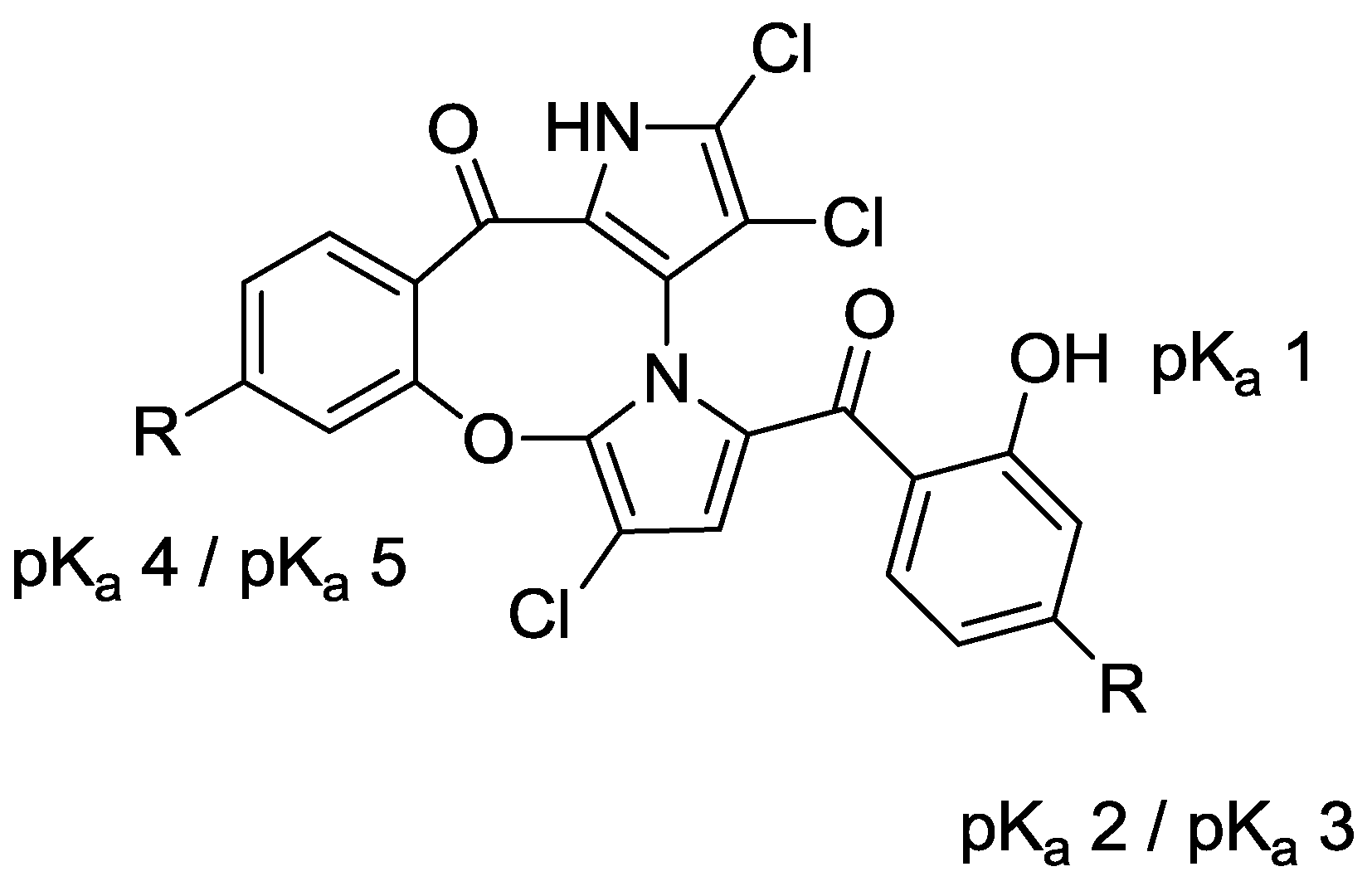

2.3. Physicochemical Properties and SAR of the Marinopyrroles

| Compound | Substituent | Mcl-1/Bim a | Bcl-xL/Bim a | pKa 1 b | pKa 2 b | pKa 3/4 b | pKa 5/6 b | Clog p b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (±)-1 | R = H | 8.9 ± 1.0 | 16.4 ± 3.3 | 7.8 | 8.4 | − | − | 5.6 |

| (+)-1 | R = H | 12.7 ± 1.0 | 19.7 ± 3.6 | 7.8 | 8.4 | − | − | 5.6 |

| (–)-1 | R = H | 12.5 ± 1.4 | 12.0 ± 2.8 | 7.8 | 8.4 | − | − | 5.6 |

| 4a | R = COOMe | 16.9 ± 2.3 | >100 | 7.5 | 8.1 | − | − | 5.9 |

| 5a | R = PO(EtO)2 | 7.7 ± 2.2 | >100 | 6.8 | 7.4 | − | − | 6.7 |

| 7a | R = COOH | 61.4 ± 7.6 | >100 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| 8a | R = PO(OH)2 | 10.9 ± 3.1 | 27.3 ± 7.2 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 0.7/5.5 c | 1.0/5.8 c | 2.4 |

| 9 | Tetrabromo-(±)-1 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 7.3 ± 0.9 | 7.8 | 8.4 | − | − | 6.7 |

| Compound | Substituent | Mcl-1/Bim a | Bcl-xL/Bim a | pKa 1 c | pKa 2/3 c | pKa 4/5 c | Clog p c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | R = OSO2CF3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 7.4 | − | − | 7.0 |

| 4 | R = COOMe | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 7.8 | − | − | 4.7 |

| 5 | R = PO(EtO)2 | >100 b | >100 | 7.1 | − | − | 5.5 |

| 6 | R = OH | 42.5 ± 6.0 | >100 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 3.8 |

| 7 | R = COOH | 66.6 ± 2.6 | >100 | 8.1 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| 8 | R = PO(OH)2 | >100 | >100 | 8.1 | 1.1/5.9 d | 0.6/5.5 d | 1.3 |

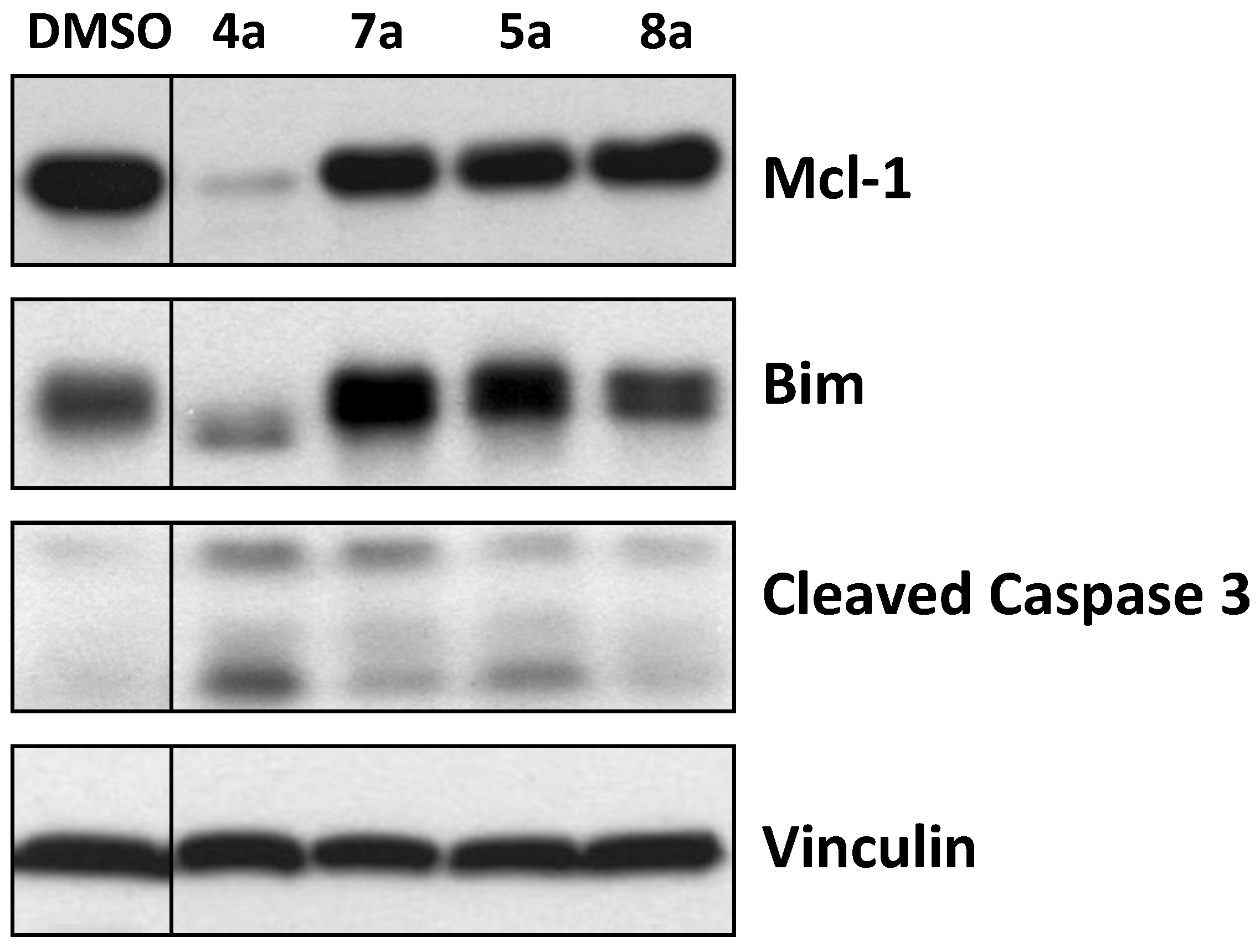

2.4. Activity in Intact Human Breast Cancer Cells

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of Marinopyrrole Derivatives

3.2. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Western Blotting Following Treatment of Intact Human Breast Cancer Cells

4. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| ADME | absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion |

| calcd. | calculated |

| DCM | dichloromethane |

| dd | double doublet |

| br | broad |

| DPPP | bis(diphenylphosphino)propane |

| DIEA | diisopropylethylamine |

| DMF | dimethylformamide |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EtOAc | ethyl acetate |

| ESI | electrospray ionization |

| HPLC | high performance liquid chromatography |

| HPO(OEt)2 | diethyl phosphanate |

| HRMS | high resolution mass spectrometry |

| HRP | horseradish peroxidase |

| IBX | 2-iodoxybenzoic acid |

| IR | infrared |

| KBr | potassium bromide |

| KF | potassium fluoride |

| LC | liquid chromatography |

| MeCN | acetonitrile |

| MeOH | methyl alcohol |

| MDA-MB-468 | breast cancer cell line |

| mp | melting point |

| MRSA | methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NCS | N-chlorosuccinimide |

| NaI | sodium iodide |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| SAR | structure activity relationship |

| s | singlet |

| TBAF | tetrabutylammonium fluoride |

| TBDMS | t-butyldimethylsilyl |

| TBDMSCl | t-butyldimethylsilyl chloride |

| Tf | trifluoromethanesulfonyl |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| tox | toxicity |

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hughes, C.C.; Prieto-Davo, A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. The marinopyrroles, antibiotics of an unprecedented structure class from a marine Streptomyces sp. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.C.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Structures, reactivities, and antibiotic properties of the marinopyrroles A–F. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3240–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Pan, L.; Chen, Y.; Song, H.; Qin, Y.; Li, R. Total synthesis of (±)-marinopyrrole A and its library as potential antibiotic and anticancer agents. J. Comb. Chem. 2010, 12, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakis, A.A.; Sarli, V. Total synthesis of (±)-marinopyrrole A via copper-mediated N-arylation. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4872–4875. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, K.C.; Simmons, N.L.; Chen, J.S.; Haste, N.M.; Nizet, V. Total synthesis and biological evaluation of marinopyrrole A and analogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 2041–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Haste, N.M.; Thienphrapa, W.; Nizet, V.; Hensler, M.; Li, R. Marinopyrrole derivatives as potential antibiotic agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (I). Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cheng, C.; Song, H. Optimization of synthetic method of marinopyrrole A derivatives. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2012, 33, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, K.; Ryan, K.S.; Gulder, T.A.; Hughes, C.C.; Moore, B.S. Flavoenzyme-catalyzed atropo-selective N,C-bipyrrole homocoupling in marinopyrrole biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12434–12437. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Clive, D.L.; Fernandopulle, S.; Chen, Z. Racemic marinopyrrole B by total synthesis. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 558–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clive, D.L.J.; Cheng, P. The marinopyrroles. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 5067–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Pan, L.; Li, J.; Qin, Y.; Li, R. Marinopyrrole derivatives as potential antibiotic agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (II). Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 2927–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, K.; Li, R.; Sung, S.S.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Manieri, W.; Krishnegowda, G.; Awwad, A.; Dewey, A.; Liu, X.; et al. Discovery of marinopyrrole A (Maritoclax) as a selective Mcl-1 antagonist that overcomes ABT-737 resistance by binding to and targeting Mcl-1 for proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10224–10235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulwerdi, F.; Liao, C.; Liu, M.; Azmi, A.S.; Aboukameel, A.; Mady, A.S.A.; Gulappa, T.; Cierpicki, T.; Owens, S.; Zhang, T.; et al. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of Mcl-1 blocks pancreatic cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanik, M.; Ishihara, K.; Yamamoto, H. Catalytic diastereoselective polycyclization of homo(polyprenyl)arene analogues bearing terminal siloxyvinyl groups. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5649–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Brown, S.G.; Harden, T.K.; Boyer, J.L.; Dubyak, G.; King, B.F.; Burnstock, G.; Jacobson, K.A. Structure-activity relationships of pyridoxal phosphate derivatives as potent and selective antagonists of P2X1 receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, K.S.; Nagabhushan, T.L. Palladium-catalyzed substituions of triflates derivaed from tyrosine-containing peptides and simpler hydroxyarenens forming 4-(diethoxyphosphinyl)phenylalanines and diethyl aryphosphonates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 2831–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.L.; Jurs, P.C. Estimation of pKa for organic oxyacids using calculated atomic charge. J. Comp. Chem. 1993, 14, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizmadia, F.; Tsantili-Kakoulidou, A.; Panderi, I.; Darvas, F. Prediction of distribution coefficient from structure. 1. Estimation method. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptak, M.D.; Gross, K.C.; Seybold, P.G.; Feldgus, S.; Shields, G.C. Absolute pK(a) determinations for substituted phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6421–6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, B.; Mohr, P.; Stahl, M. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2601–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasis, M.E.; Forinash, K.D.; Chen, Y.A.; Fulp, W.J.; Coppola, D.; Hamilton, A.D.; Cheng, J.Q.; Sebti, S.M. Combination of farnesyltransferase and Akt inhibitors is synergistic in breast cancer cells and causes significant breast tumor regression in ErbB2 transgenic mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, C.; Liu, Y.; Balasis, M.E.; Simmons, N.L.; Li, J.; Song, H.; Pan, L.; Qin, Y.; Nicolaou, K.C.; Sebti, S.M.; et al. Cyclic Marinopyrrole Derivatives as Disruptors of Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL Binding to Bim. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1335-1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12031335

Cheng C, Liu Y, Balasis ME, Simmons NL, Li J, Song H, Pan L, Qin Y, Nicolaou KC, Sebti SM, et al. Cyclic Marinopyrrole Derivatives as Disruptors of Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL Binding to Bim. Marine Drugs. 2014; 12(3):1335-1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12031335

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Chunwei, Yan Liu, Maria E. Balasis, Nicholas L. Simmons, Jerry Li, Hao Song, Lili Pan, Yong Qin, K. C. Nicolaou, Said M. Sebti, and et al. 2014. "Cyclic Marinopyrrole Derivatives as Disruptors of Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL Binding to Bim" Marine Drugs 12, no. 3: 1335-1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12031335