A Comprehensive Review of One-Dimensional Metal-Oxide Nanostructure Photodetectors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Different Photodetector Materials—Metal Oxides

2.1. ZnO-Based Photodetectors

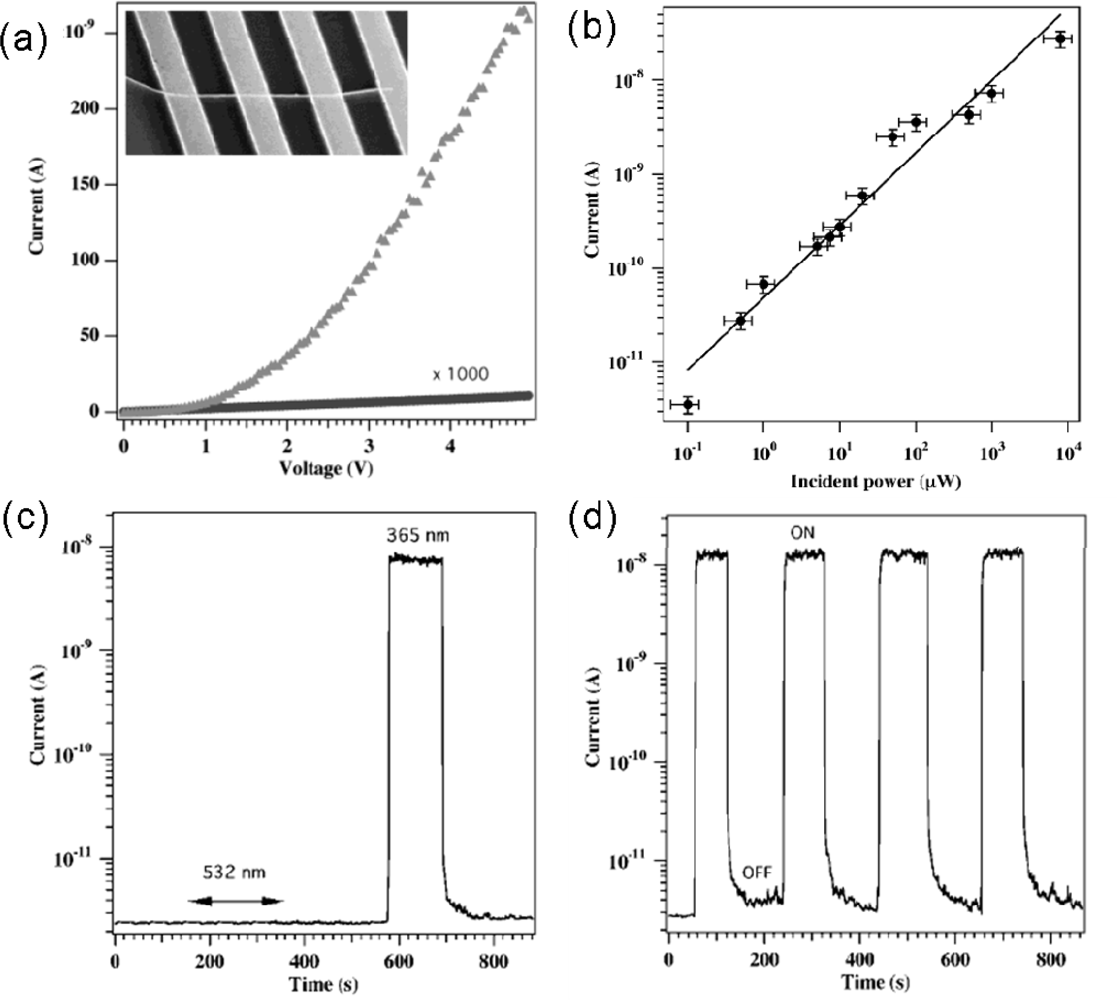

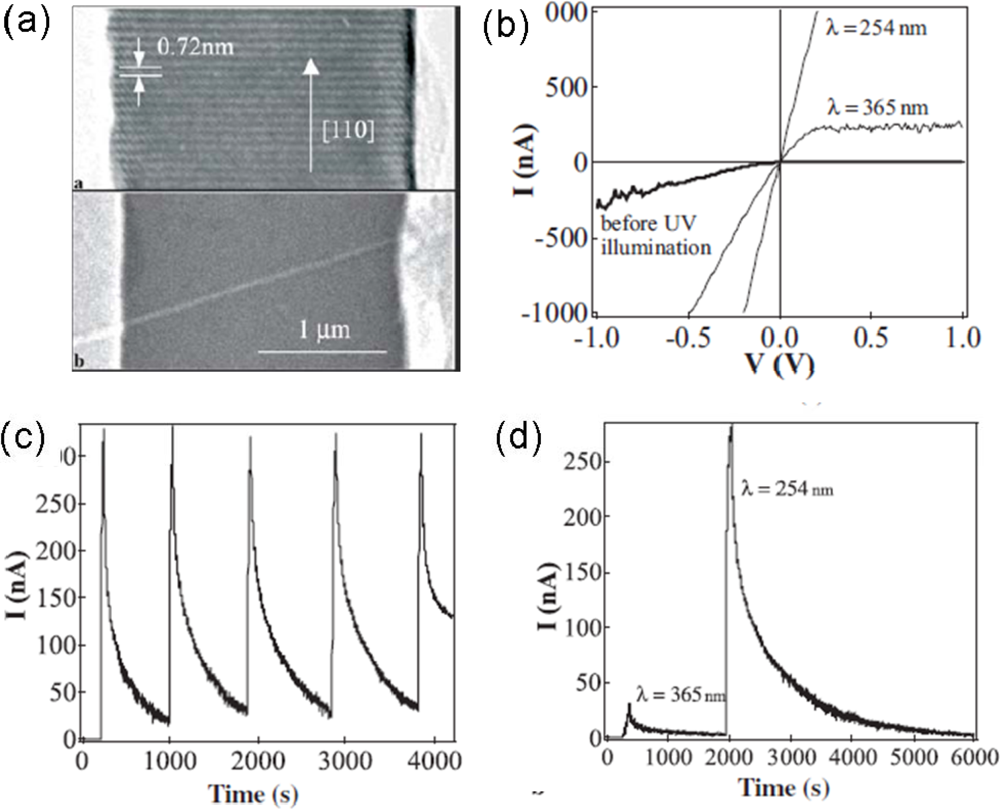

2.2. SnO2-Based Photodetectors

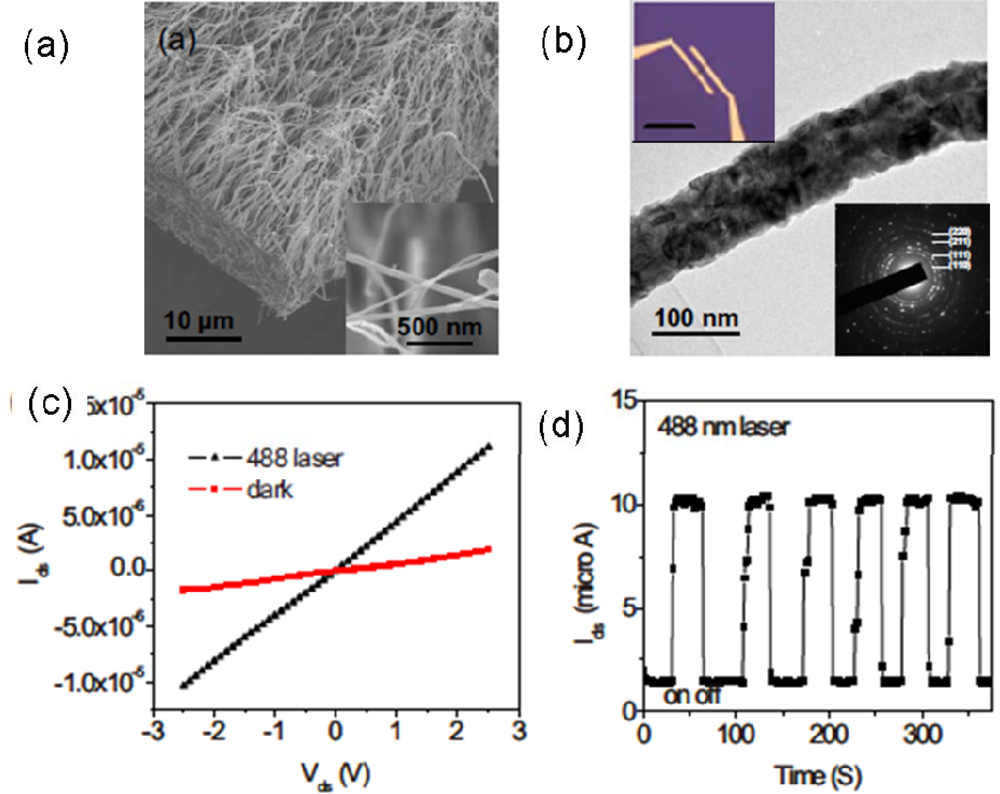

2.3. Cu2O-based photodetectors

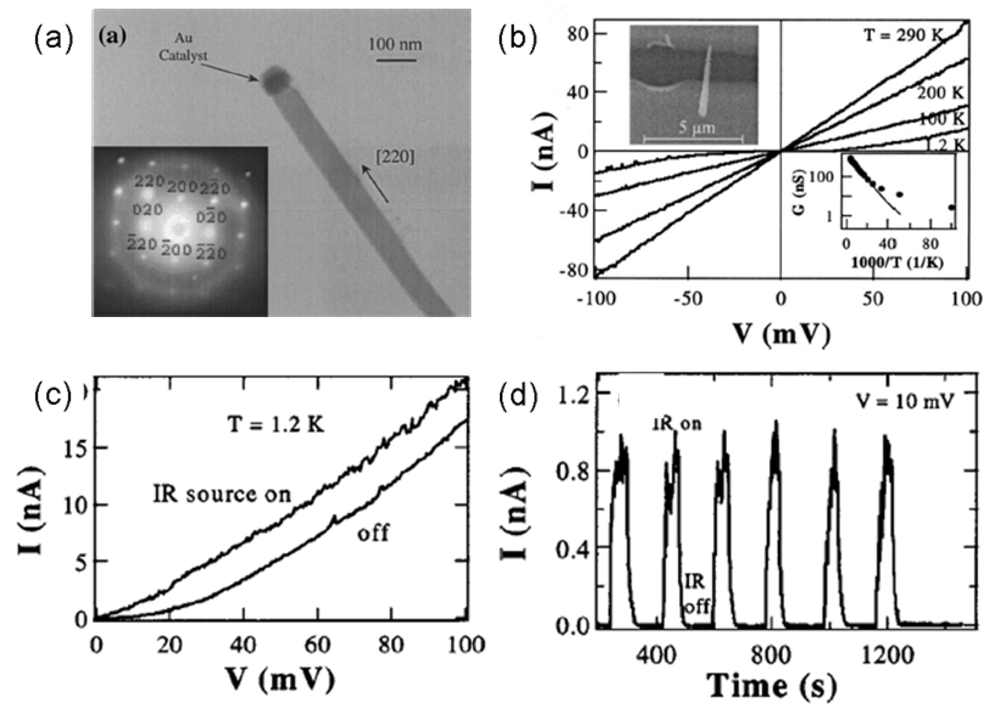

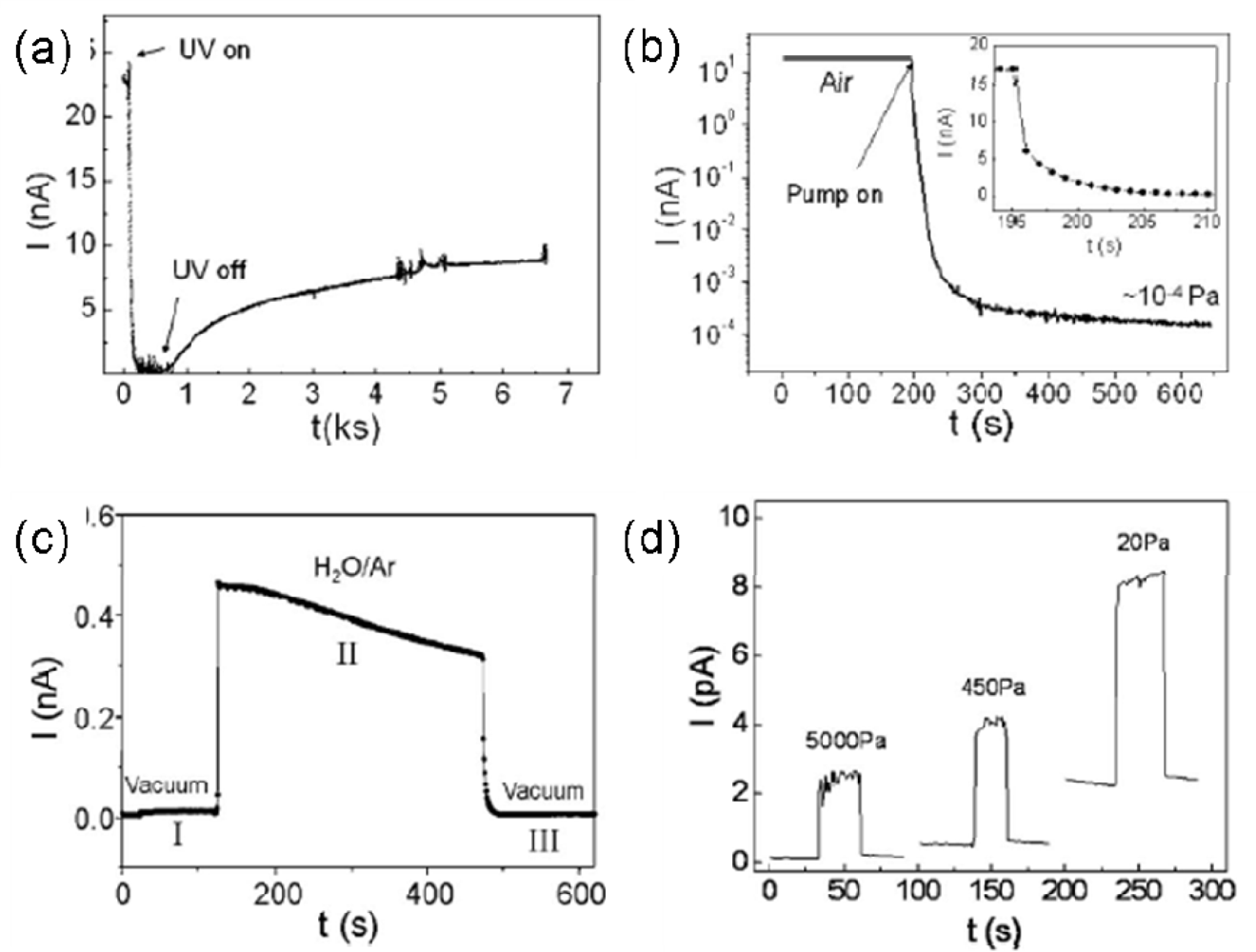

2.4. Ga2O3-based photodetectors’

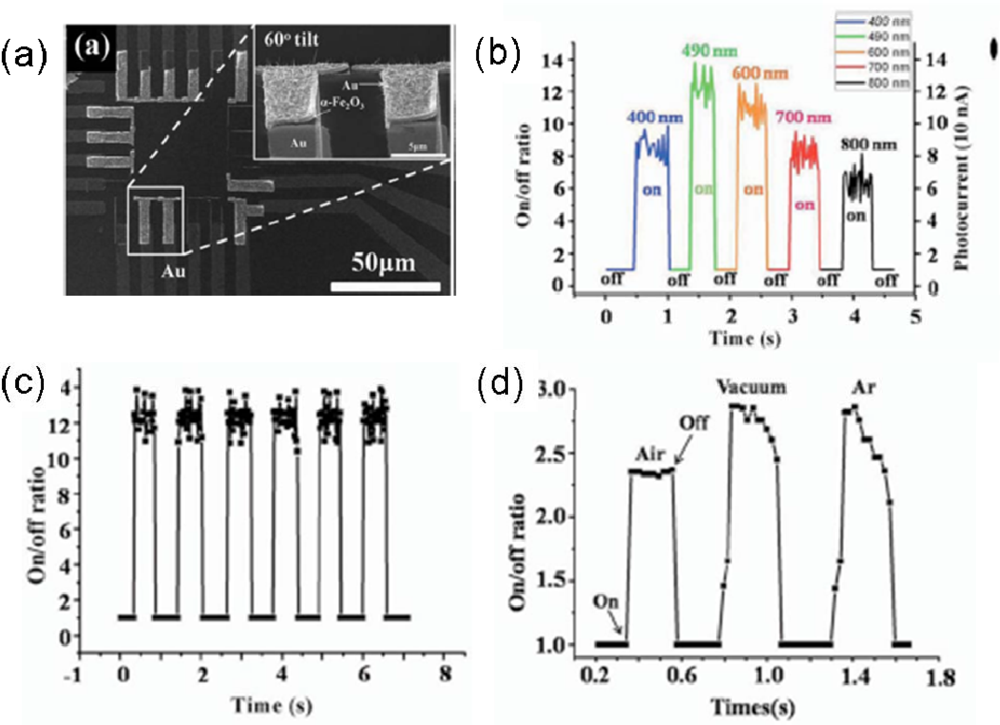

2.5. Fe2O3-based photodetectors

2.6. In2O3-Based Photodetector

2.7. CdO-Based Photodetectors

2.8. CeO2-Based Photodetectors

2.9. Ternary Oxide-Based Photodetectors

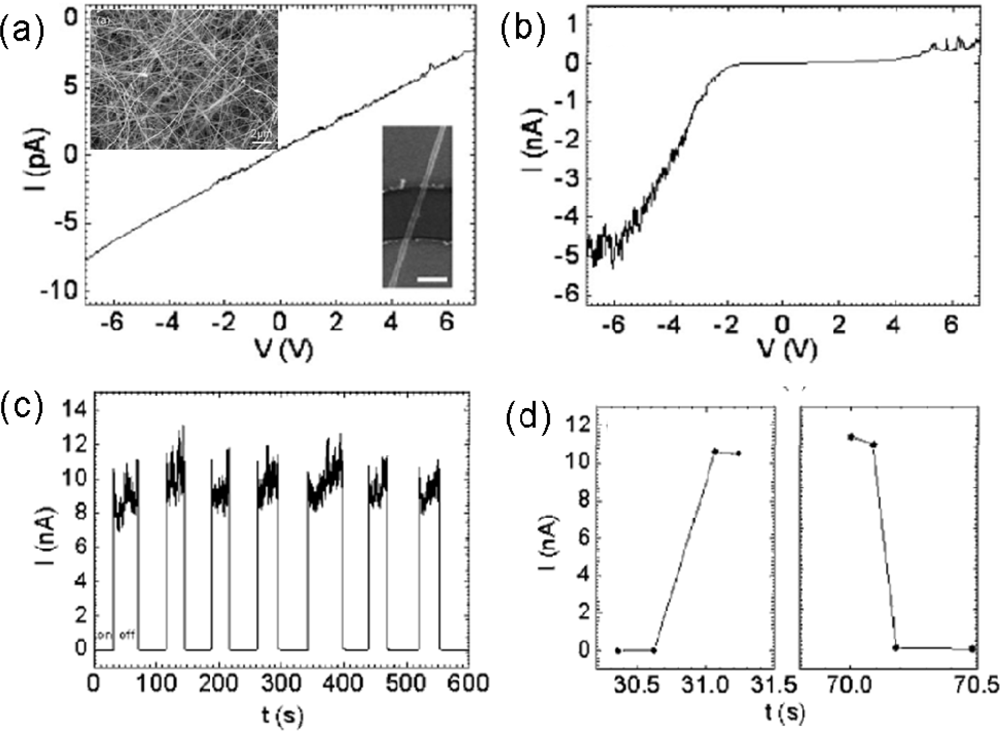

2.9.1. ZnSnO3-based photodetectors

2.9.2. ZnGa2O4-based photodetectors

2.9.3 RuO2/TiO2 core/shell nanowire-based photodetectors

3. Conclusions and Outlook

- Nanomaterial fabrication: As known, the material is the milestone of a device. The growth kinetics and thermodynamics involved in the synthesis of metal-oxide nanostructures are extremely complex, and presume different mechanisms under different growth conditions. Although comprehensive efforts have been made towards the synthesis of high-quality metal-oxide nanostructures, significant challenges still exist in their syntheses that include, but not limited to, reliable control of diameter, length, orientation, density, crystallization and hierarchical assembly.

- Device fabrication: In the conventional “pick and place” method, 1D nanostructures fabricated by vapor synthesis process are first collected from substrates on which they were initially grown and then, dispersed randomly on an insulating substrate after being diluted in a solution. Sophisticated techniques such as photolithography, electron beam lithography or focused ion beam are required to make metallic contacts to the nanostructures. Out of question, this process is complicated, time-consuming and uneconomic, thus hampering the development of practical routes [21]. It still remains a grand challenge to construct a device via a simple and effective method. Furthermore, since the performance of devices critically depends on the quality of the Ohmic contacts between a nanostructure and the electrodes, the construction of reliable and stable contacts is an urgent task that deserves particular attention.

- Sensitivity, selectivity and stability (3S): Next generation photodetectors will require significant improvements in sensitivity, selectivity and stability (3S) in order to meet the future demands in variety of fields. Though some research groups have successfully detected light using 1D metal oxide nanostructures, the selectivity and stability are still quite low.

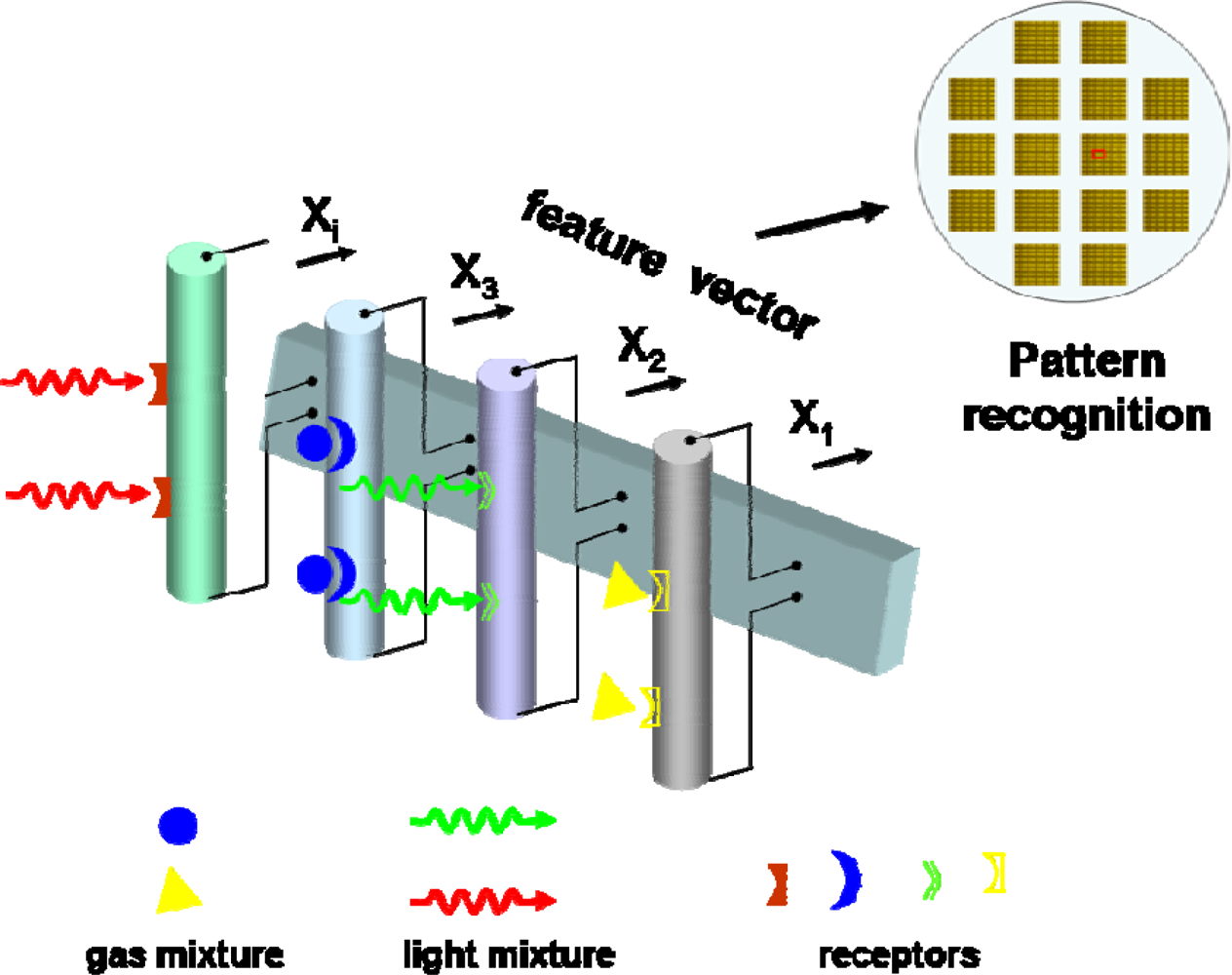

- Multi-functional detectors: The evolution of photodetectors goes in parallel with the development of microelectronics in which the architecture of photodetector elements is influenced by design trends in planar electronics. One of the major goals is to design nanodetectors that could be easily integrated into modern electronic fabrication technologies [8]. A possible avenue to differentiate the 1D nanostructure response maybe surface coating with chemical selective membrane, surface medication by specific functional groups, or combing multi-light and/or multi-gas sensing modules coupled with signal processing functions, acting as an “electronic nose” to differentiate in a more complex environment (Figure 11).

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Yang, P.D.; Yan, H.Q.; Mao, S.; Russo, R.; Johnson, J.; Saykally, R.; Morris, N.; Pham, J.; He, R.; Choi, H.J. Controlled growth of ZnO nanowires and their optical properties. Adv. Mater 2002, 12, 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, T.Y.; Zhong, H.Z.; Gu, Z.J.; Peng, A.D.; Fu, H.B.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.F.; Yao, J.N. Manipulation of the morphology of ZnSe sub-micro structures using CdSe nanocrystals as the seeds. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 2980–2986. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, C.M.; Wang, Z.L. Functional nanowires. MRS Bull 2007, 32, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.S.; Bando, Y.; Gautam, U.K.; Ye, C.H.; Golberg, D. Inorganic semiconductor nanostructures and their field-emission applications. J. Mater. Chem 2008, 18, 509–522. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.N.; Yang, P.D.; Sun, Y.G.; Wu, Y.Y.; Mayers, B.; Gates, B.; Yin, Y.D.; Kim, F.; Yan, H.Q. One-dimensional nanostructures: synthesis, characterization and applications. Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 353–389. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.Z.; Chen, P.C.; Ryu, K.; Zhou, C.W. Devices and chemical sensing applications of metal oxide nanowires. J. Mater. Chem 2009, 19, 828–839. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.G.; Chang, P.C.; Fan, Z.Y. Quai-one-dimensional metal oxide materials-synthesis, properties and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2006, 52, 49–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmakov, A.; Moskovits, M. Chemical sensing and catalysis by one-dimensional metal-oxide nanostructures. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res 2004, 34, 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Soci, C.; Zhang, A.; Xiang, B.; Dayeh, S.A.; Aplin, D.P.R.; Park, J.; Bao, X.Y.; Lo, Y.H.; Wang, D. ZnO nanowire UV photodetectors with high internal gain. Nano Lett 2007, 7, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Jie, J.S.; Meng, X.M.; Fan, X.; Lee, S.T. Photoresponse properties of CdSe single-nanoribbon photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater 2007, 17, 1795–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, M.Y.; Koide, Y.; Alvarez, J.; Imura, M.; Kleider, J.P. Persistent positive and transient absolute negative photoconductivity observed in diamond photodetectors. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 045112:1–045112:9. [Google Scholar]

- Kind, H.; Yan, H.Q.; Messer, B.; Law, M.; Yang, P.D. Nanowire ultraviolet photodetectors and optical switches. Adv. Mater 2002, 14, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H.; Chang, P.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsai, K.T. Electrical and optoelectronic characterization of a ZnO nanowire contacted by focused-ion-beam-deposited Pt. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 135701:1–135701:5. [Google Scholar]

- Prades, J.D.; Hernandez-Ramirez, F.; Jimenez-Diaz, R.; Manzanares, M.; Andreu, T.; Cirera, A.; Romano-Rodriguez, A.; Morante, J.R. The effects of electron-hole separation on the photoconductivity of individual metal oxide nanowires. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 465501:1–465501:7. [Google Scholar]

- Comini, E.; Baratto, G.; Faglia, G.; Ferroni, M.; Vomiero, A.; Sberveglieri, G. Quasi-one dimensional metal oxide semiconductors: preparation, characterization and application as chemical sensors. Prog. Mater. Sci 2009, 54, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.L. Splendid one-dimensional nanostructures of zinc oxide: a new nanomaterial family for nanotechnology. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.L. Functional oxide nanobelts: materials, properties and potential applications in nanosystems and biotechnology. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2004, 55, 159–196. [Google Scholar]

- Prades, J.D.; Jimenez-Diaz, R.; Hernandez-Ramirez, F.; Fernandez-Romero, L.; Andreu, T.; Cirera, A.; Romano-Rodriguez, A.; Cornet, A.; Morante, J.R.; Barth, S.; Mathur, S. Towards a systematic understanding of photodetectors based on individual metal oxide nanowires. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 14639–14644. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Chu, K.S. ZnO nanowire field-effect transistor as a UV photodetector; optimization for maximum sensitivity. Phys. Status. Solidi. A 2009, 206, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.D.; Wu, H.; Pan, W. Photoswitches and memories assembled by electrospinning aluminum-doped zinc oxide single nanowires. Adv. Mater 2007, 19, 3968–3972. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.B.; Valle, F.D.; Simonnet, M.; Yamada, I.; Delaunay, J.J. High-performance UV detector made of ultra-long ZnO bridging nanowires. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 045501:1–045501:5. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.P.; Zhang, Y.J.; Guo, R.Y. ZnO microtube ultraviolet detectors. J. Cryst. Growth 2008, 310, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Chang, P.C.; Lu, J.G.; Walter, E.C.; Penner, R.M.; Lin, C.H.; Lee, H.P. Photoluminescence and polarized photodetection of single ZnO nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett 2004, 85, 6128–6130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Gu, Y.D.; Hu, Y.F.; Mai, W.J.; Yeh, P.H.; Bao, G.; Sood, A.K.; Polla, D.L.; Wang, Z.L. Gigantic enhancement in response and reset time of ZnO UV nanosensor by utilizing Schottky contact and surface functionalization. Appl. Phys. Lett 2009, 94, 191103:1–191103:3. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Yong, K. Photoconductivity of vertically aligned ZnO nanoneedle array. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2008, 26, 1933–1936. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Dutta, D.; Chien, C.J.; Chen, H.Y.; Brown, E.C.; Chang, P.C.; Lu, J.G. Electrical and photoconductive properties of vertical ZnO nanowires in high density arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett 2006, 89, 213110:1–213110:3. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J.B.K.; Thong, J.T.L. Simple fabrication of a ZnO nanowire photodetector with a fast photoresponse time. Appl. Phys. Lett 2006, 88, 133114:1–133114:3. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Zhai, J.L.; Wang, D.J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, S.; Xie, T.F. Anomalous photoconductivity of cobalt-doped zinc oxide nanobelts in air. Chem. Phys. Lett 2008, 456, 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Harnack, O.; Pacholski, C.; Weller, H.; Yasuda, A.; Wessels, J.M. Rectifying behavior of electrically aligned ZnO nanorods. Nano Lett 2003, 3, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Keem, K.; Kim, H.; Kim, G.T.; Lee, J.S.; Min, B.; Cho, K.; Sung, M.Y.; Kim, S. Photocurrent in ZnO nanowires grown from Au electrodes. Appl. Phys. Lett 2004, 84, 4376–4378. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.H.; Wan, Q.; Liang, Y.X.; Wang, T.H. Electronic transport through individual ZnO nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett 2004, 84, 4556–4558. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H.; Lin, Y.H.; McConney, M.E.; Tsukruk, V.V.; Wang, Z.L.; Bao, G. Enhancing UV photoconductivity of ZnO nanobelt by polyacrylonitrile functionalization. J. Appl. Phys 2007, 102, 084303:1–084303:4. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, Y.W.; Kang, B.S.; Tien, L.C.; Norton, D.P.; Ren, F.; Laroche, J.R.; Pearton, S.J. UV photoresponse of single ZnO nanowires. Appl. Phys. A 2005, 80, 497–499. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chang, S.J.; Lin, Y.R.; Li, P.C.; Lin, T.S.; Tsai, S.Y.; Lu, T.H.; Chen, I.C. Ultraviolet photodetectors with low temperature synthesized vertical ZnO nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett 2005, 416, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Mao, S.S.; Lin, L.W. Fabrication and characterization of ZnO nanowires based UV photodiodes. Sens. Actuat. A 2006, 127, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, R.; Dutta, M.; Basak, D. Self-seeded growth and ultraviolet photoresponse properties of ZnO nanowire arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett 2007, 91, 073108:1–073108:3. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.E.; Ji, H.J.; Kim, K.; Kim, G.T.; Bae, C.H.; Park, S.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Ha, J.S. Origin of the slow photoresponse in an individual sol-gel synthesized ZnO nanowire. Appl. Phys. Lett 2007, 90, 153106:1–153106:3. [Google Scholar]

- Kouklin, N. Cu-doped ZnO nanowires for efficient and multispectral photodetection applications. Adv. Mater 2008, 20, 2190–2194. [Google Scholar]

- Aga, R.S.; Jowhar, D.; Ueda, A.; Pan, Z.; Collins, W.E.; Mu, R.; Singer, K.D.; Shen, J. Enhanced photoresponse in ZnO nanowires decorated with CdTe quantum dot. Appl. Phys. Lett 2007, 91, 232108:1–232108:3. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.E.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kang, B.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, G.T. Photoresponse of sol-gel-synthesized ZnO nanorods. Appl. Phys. Lett 2004, 84, 5022–5024. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y.; Yun, Y.S.; Hong, Y.S.; Oh, H.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, S.S. Synthesis, electrical and photoresponse properties of vertically well-aligned and epitaxial ZnO nanorods on GaN-buffered sapphire substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett 2005, 87, 123108:1–123108:3. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Wang, Z.Z.; Liu, K.H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.L.; Bai, X.D.; Wang, E.G. Photoconducting response on bending of individual ZnO nanowires. J. Mater. Chem 2009, 19, 1002–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.S.; Avouris, P.; Pan, Z.W.; Wang, Z.L. Field-effect transistors based on single semiconducting oxide nanobelts. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 659–663. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.C.; Lin, W.H.; Li, Y.Y. Synthesis of ZnO nanowires and their applications as an ultraviolet photodetector. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 2009, 9, 2813–2819. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.L.; Hsueh, T.J.; Chang, S.P. Preparation of ZnO nanoflakes and a nanowire-based photodetector by localized oxidation at low temperature. J. Electrochem. Soc 2008, 155, K59–K62. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Zhang, D.H.; Han, S.; Li, C.; Tang, T.; Jin, W.; Liu, X.L.; Lei, B.; Zhou, C.W. Laser ablation synthesis and electron transport studies of Tin Oxide nanowires. Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 1754–1757. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.; Barth, S.; Shen, H.; Pyun, J.C.; Werner, U. Size-dependent photoconductance in SnO2 nanowires. Small 2005, 1, 713–717. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Yan, B.; Hao, Y.F.; Xing, G.Z.; Liu, J.P.; Zhao, B.C.; Shen, Z.X.; Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Thong, J.T.L.; Li, C.M.; Huang, W.; Yu, T. P-type electrical, photoconductive, and anomalous ferromagnetic properties of Cu2O nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett 2009, 94, 113106:1–113106:3. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Chiang, C.K.; Chang, H.T. Synthesis of fluorescent and photovoltaic Cu2O nanocubes. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 025604:1–025604:7. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.P.; Neti, N.R.; Sinha, A.S.K.; Srivastava, O.N. Growth of different nanostructures of Cu2O (nanothreads, nanowires, and nanocubes) by simple electrolysis based oxidation of copper. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, P.; Zhang, J.Y.; Li, Q.H.; Wang, T.H. Individual β-Ga2O3 nanowires as solar-blind photodetectors. Appl. Phys. Lett 2006, 88, 153107:1–153107:3. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.Q.; Li, Q.; Zhan, J.H.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, Z.W.; Ringer, S.P.; Bando, Y.; Golberg, D. Unconventional ribbon-shaped β-Ga2O3 tubes with mobile Sn nanowire fillings. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, P.; Xue, X.Y.; Liu, Y.G.; Wan, Q.; Wang, T.H. Achieving fast oxygen response in individual β-Ga2O3 nanowires by ultraviolet illumination. Appl. Phys. Lett 2006, 89, 112114:1–112114:3. [Google Scholar]

- Eranna, G.; Joshi, B.C.; Runthala, D.P.; Gupta, R.P. Oxide materials for development of integrated gas sensors—a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mat. Sci 2004, 29, 111–188. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, Q.; Gu, C.Z.; Tang, C.C.; Bando, Y.; Golberg, D. Quasi-aligned Ga2O3 nanowires grown on brass wire meshes and their electrical and field-emission properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 1980–1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.C.; Kuo, Y.P.; Li, Y.Y. On-chip fabrication of an individual α-Fe2O3 nanobridge and application of ultrawide wavelength visible-infrared photodetector/optical switching. Appl. Phys. Lett 2009, 94, 133108:1–133108:3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Li, C.; Han, S.; Liu, X.; Tang, T.; Jin, W.; Zhou, C. Ultraviolet photodetection properties of indium oxide nanowires. Appl. Phys. A 2003, 77, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.H.; Li, C.; Han, S.; Liu, X.L.; Tang, T.; Jin, W.; Zhou, C.W. Electronic transport studies of single-crystalline In2O3 nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett 2003, 82, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, D.H.; Han, S.; Liu, X.L.; Tang, T.; Zhou, C.W. Diameter-controlled grown of single-crystalline In2O3 nanowires and their electronic properties. Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.L.; Li, C.; Han, S.; Han, J.; Zhou, C.W. Synthesis and electronic transport studies of CdO nanoneedles. Appl. Phys. Lett 2003, 82, 1950–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.Q.; Wang, C.; Feng, P.; Wang, T.H. Anomalous photoconductivity of CeO2 nanowire in air. Appl. Phys. Lett 2007, 91, 073104:1–073104:3. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Mai, H.X.; Yuan, Q.; Lu, H.B.; Li, J.C.; Liu, C.; Yan, C.H.; Shen, Z.X.; Yu, T. Single CeO2 nanowire gas sensor supported with Pt nanocrystals: gas sensitivity, surface bond states, and chemical mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 9061–9065. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.Y.; Guo, T.L.; Lin, Z.X.; Wang, T.H. Individual core-shell structured ZnSnO3 nanowires as photoconductors. Mater. Lett 2008, 62, 1356–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, P.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wan, Q.; Wang, T.H. Photocurrent characteristics of individual ZnGa2O4 nanowires. J. Appl. Phys 2007, 102, 074309:1–074309:5. [Google Scholar]

- Chueh, Y.L.; Hsieh, C.H.; Chang, M.T.; Chou, L.J.; Lao, C.S.; Song, J.H.; Gan, J.Y.; Wang, Z.L. RuO2 nanowires and RuO2/TiO2 core/shell nanowires: from synthesis to mechanical, optical, electrical, and photoconductive properties. Adv. Mater 2007, 19, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.J.; Zhu, C.L.; Cao, M.S.; Wang, T.H. Photoresponse of SnO2 nanobelts grown in situ on interdigital electrodes. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 285502:1–285502:5. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, R.S.; Chen, T.T.; Chen, H.Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Chen, K.H.; Chen, L.C. High photocurrent gain in SnO2 nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett 2008, 93, 112115:1–112115:3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Q.; Lao, C.S.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.Z.; Xie, Z.X.; Zheng, L.S.; Wang, Z.L. Enhancing the photo-and gas-sensing properties of a single SnO2 nanowire based nanodevice by nanoparticle surface functionalization. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 11539–11544. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Shao, M.W.; Wang, X.H.; Hu, H.B. Single-crystalline Molybdnum Trioxide nanoribbons: photocatalytic, photoconductive, and electrochemical properties. Chem. Eur. J 2009, 15, 2310–2316. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, N.; Ebina, Y.; Takada, K.; Sasaki, T. Photocurrent generation from semiconducting Manganese Oxide nanosheets in response to visible light. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 9651–9655. [Google Scholar]

| Metal oxides | Crystal structures | Conductive type | Band gap/eV | Sensing light |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | Hexagonal | n | 3.37 | UV |

| SnO2 | Tetragonal | n | 3.6 | UV |

| Cu2O | Cubic | p | 2.17 | Visible |

| β-Ga2O3 | Monoclinic | n | 4.2–4.9 | UV |

| α-Fe2O3 | Rhombohedral | n | 2.1 | Visible |

| In2O3 | Cubic | n | 3.6 (direct) 2.5 (indirect) | UV |

| CdO | Cubic | n | 2.27 (direct) 0.55 (indirect) | Visible/IR |

| CeO2 | Cubic | n | 3.2 | UV |

| Nanostructures | Devices | Light of detection | Bias | Dark current Or conductance | Photocurrent Or conductance | Photocurrent and Dark current ratio | Rise time | Decay time | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW | Resistor | 390 nm; 6.3–40 mW/cm2 | 5 | 1–10 nA | 100 μA | 102–105 | — | — | [9] |

| NW | Resistor | 365nm; 0.3 mW/cm2 | 0–5 | ∼1 pA | ∼250 nA | 104–106 | <1 s | <1 s | [12] |

| NW | Resistor | 325 nm | 0.5 | ∼0.05 μA | ∼0.4 μA | — | — | — | [13] |

| NW | Resistor | 340 nm | 1 | — | 20 nA | 170 s | 300 s | [18] | |

| NW | FET | 365 nm; 0.47 mW/cm2 | — | — | — | 102–106 | — | — | [19] |

| Al-ZnO NW | Resistor | 400–800 nm | — | 3.36×10−4 S/cm | 6.67×10−4 S/cm | — | — | — | [20] |

| NW | Resistor | 350 nm; 50 nW-48 mW/cm2 | 5 | — | 40 μA for 50 nW/cm2 | 10–105 | 0.7 s | 1.4 s | [21] |

| MT | Resistor | 365 nm; 21700 μW/cm2 | 5 | 1.5 μA | 0.085 mA (O2) 0.135 mA (air) 0.209 mA (N2) 0.201 mA (Ar) | — | 2.9 s 5.9 s 28.4 s 45.8 s | 100 s 638 s — — | [22] |

| NW | Resistor | 633 nm; 0.2 W/cm2 | 2 | 13.1 nS | 73.4 nS | — | — | — | [23] |

| ST ZnO NW | Resistor | 365 nm; 30 μW/cm2 | 1 | 0.04 nA | 60 nA | 1500 | 0.6 s | 6 s | [24] |

| Nanoneedle array | Resistor | 365 nm; 16 μW/cm2 | — | 1.0×10−4 A | 4.0×10−4 A | — | — | — | [25] |

| NW | Resistor | 300–425 nm; 6 mW/cm2 | 10 | 20 nA | 140 nA | — | — | — | [26] |

| NW array | Resistor | 370 nm | 5 | 70 μA | 100 μA | — | 0.4 ms | — | [27] |

| Co- ZnO NB | Resistor | 370 nm | — | 1.3 μA | 110 μA | — | — | — | [28] |

| 630 nm | 0.25 μA | 500 s | |||||||

| NR | Resistor | 366 nm; 0.1 W/cm2 | 1 | 1200–4000 MΩ | 20–500 MΩ | — | — | — | [29] |

| NW | Resistor | 325 nm; 10 mW/cm2 | 0.5 | — | — | — | — | — | [30] |

| NW | Resistor | 254 nm; 7 W | — | 0.08 μS | 2 μS | 5.8 (Vacuum) 66 (air) | 16 s (V) 66 s (air) | 188 s (V) 115 s (air) | [31] |

| ZnO NB PPAN-ZnO NB | Resistor | 365 nm; 100 W | — | — | — | 112% 9000% | — | — | [32] |

| NW | Resistor | 254 nm (0.1 W/cm2) 366 nm (0.1 W/cm2) | 0.25 | 100 nA | 580 nA (254 nm) 700 nA (366 nm) | — | — | Tens of Seconds | [33] |

| NW array | Resistor | 365 nm; 0.3 mW/cm2 | 5 | 1.35×10−5 A | 2.0×10−7 A | 150 | — | — | [34] |

| NW array | Resistor | 365 nm; 25 μW | 20 | 0.15 μA | 1.8 μA | — | — | — | [35] |

| NW arrays | Resistor | 350 nm | 5 | — | — | 11, 64 | — | — | [36] |

| NW | Resistor | 325 nm | 5 | — | 0.35 nA | — | 43.7 s (V) 4.6 s | — | [37] |

| Cu- ZnO NW | Resistor | 365 nm; 5 mW/cm2 | 10 | 10 pA | 100 nA | 7000 | — | — | [38] |

| Visible; 10 mW/cm2 | — | 5000 | |||||||

| NW with CdTe QD | Resistor | 450 nm; 10 mW/cm2 | 2 | 109 Ω | 12 nA | — | 4.7 s | — | [39] |

| NR | Resistor | 325 nm | 2 | 1 nA | 22 nA | — | 3.7 s | 63.6 s | [40] |

| NR | FET | 254 nm | 0.2 | — | 2.4 μA | 103 | — | 30 min | [41] |

| NW | Resistor | 380 nm | 5 | 2.5 nA | 4.5 nA | — | — | 17.0 s | [42] |

| NB | FET | 350 nm | 6.5 | — | — | — | — | — | [43] |

| NW | Resistor | 365 nm | 2 | 2 μA | 15 μA | — | 45 s | 55 s | [44] |

| NF/NWs | Resistor | 115–400 nm; 150 W | 10 | 7.38 nA | 38.62 | — | — | — | [45] |

| Metal oxides | Nanostructures | Devices | Light of detection | Bias (V) | Dark current or conductance | Photocurrent or conductance | Photocurrent and Dark current ratio | Rise time | Decay time | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnO2 | NW | Resistor | 370 nm | — | 37.5 kΩ | 12.5 kΩ | — | — | — | [47] |

| NW | FET | 254 nm | 0.05 | 0.66 nS | 760 nS | 103 | — | < 0.1 s | [46] | |

| NB | Resistor | 254 nm; 10 mW | −5 | 0.4 nA | 80 μA (air) 900 μA (vacuum) | 105 (air) 106 (vacuum) | — | — | [66] | |

| 532 nm; 0.1–35.1 mW | 1.4 nA | 57 nA | — | < 1 s | < 1 s | |||||

| NW | Resistor | 325 nm; 100 W/m2 | 0.1 | 30 nA (air) | 210 nA (air) 1.2 μA (Vacuum) | — | — | — | [67] | |

| NW | Resistor | 365 nm | — | 200 nA | 235 nA | — | — | — | [68] | |

| ZnO-functional SnO2 NW | — | 300 nA | 1.50 | — | — | |||||

| Cu2O | NW | Resistor | 488 nm | 3 | 0.7 μS | 4.3 μS | ∼6 | < 3 s | < 3 s | [48] |

| β-Ga2O3 | NW | Resistor | 254 nm; 7 w | 8 | Several pA (15 pA) | Several nA (10 nA) | ∼1000 | 0.22 s | 0.09s | [51] |

| NW | Resistor | 254 nm | 20 | ∼26 pA | ∼0.56–0.0095 nA (PO2 = 22–20000 Pa) | — | — | — | [53] | |

| CdO | ND | Resistor | 950 nm | 0.01 | 13.3 nS | 114.5 nS | 8.6 | — | — | [60] |

| In2O3 | NW | FET | 254 nm 365nm | 0.3 | — | 290 nA (254 nm) 33nA (365nm) | — | 10 s | — | [57] |

| CeO2 | NW film | Resistor | 254 nm; 7W | 5 | 22.8 nA (air) 0.35 pA (H2O) | 0.25 nA (air) 0.44 nA (H2O) | ∼1000 | 300 s (air) 2 s (H2O) | — | [61] |

| α-Fe2O3 | NB | Resistor | 400–800 nm; 0.5 mW/cm2 | 0.8 | 10 nA | 123 nA (490 nm) | 11–12 | 20 ms | — | [56] |

| α-MoO3 | NB | Resistor | 400–700 nm; 10 W | 0.1 | — | 0.22 μA | — | — | — | [69] |

| MnO2 | Nanosheet film | Resistor | 450 nm | — | — | — | — | — | — | [70] |

| ZnSnO3 | NW | Resistor | UV light; Green laser | — | 0.3 nA | 162 nA (UV) 6.6 nA (green) | — | 20 s | — | [63] |

| ZnGa2O4 | NW | Resistor | UV light | 30 | 8.5 PA | 1 nA | — | — | — | [64] |

| RuO2/TiO2 | Core/Shell NW | Resistor | 256 nm | — | 18.5 μA | 19.4 μA | — | 307 s | 437 s | [65] |

© 2009 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhai, T.; Fang, X.; Liao, M.; Xu, X.; Zeng, H.; Yoshio, B.; Golberg, D. A Comprehensive Review of One-Dimensional Metal-Oxide Nanostructure Photodetectors. Sensors 2009, 9, 6504-6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90806504

Zhai T, Fang X, Liao M, Xu X, Zeng H, Yoshio B, Golberg D. A Comprehensive Review of One-Dimensional Metal-Oxide Nanostructure Photodetectors. Sensors. 2009; 9(8):6504-6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90806504

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhai, Tianyou, Xiaosheng Fang, Meiyong Liao, Xijin Xu, Haibo Zeng, Bando Yoshio, and Dmitri Golberg. 2009. "A Comprehensive Review of One-Dimensional Metal-Oxide Nanostructure Photodetectors" Sensors 9, no. 8: 6504-6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90806504

APA StyleZhai, T., Fang, X., Liao, M., Xu, X., Zeng, H., Yoshio, B., & Golberg, D. (2009). A Comprehensive Review of One-Dimensional Metal-Oxide Nanostructure Photodetectors. Sensors, 9(8), 6504-6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90806504