Abstract

In this study, information pertaining to the development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology for improving the performance of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems was collected. Among the 18 AI tools developed for HVAC control during the past 20 years, only three functions, including weather forecasting, optimization, and predictive controls, have become mainstream. Based on the presented data, the energy savings of HVAC systems that have AI functionality is less than those equipped with traditional energy management system (EMS) controlling techniques. This is because the existing sensors cannot meet the required demand for AI functionality. The errors of most of the existing sensors are less than 5%. However, most of the prediction errors of AI tools are larger than 7%, except for the weather forecast. The normalized Harris index (NHI) is able to evaluate the energy saving percentages and the maximum saving rations of different kinds of HVAC controls. Based on the NHI, the estimated average energy savings percentage and the maximum saving rations of AI-assisted HVAC control are 14.4% and 44.04%, respectively. Data regarding the hypothesis of AI forecasting or prediction tools having less accuracy forms Part 1 of this series of research.

1. Introduction

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems provide a suitable living environment with thermal comfort and air quality. These mechanic–electrical systems include several types, such as air conditioners, heat pumps, furnaces, boilers, chillers, and packaged systems [1]. In most of the countries, the building sector accounts for nearly 40% of the total consumed energy [2]. For every building type, HVAC and lighting systems occupy more than half of the energy consumption [3]. A large fraction of the increasing energy expenditure for the buildings was because of the extending HVAC installations for better thermal comfort and air quality [4]. Therefore, the HVAC system plays an important role in the energy efficiency of buildings. Improving the control of HVAC operations and the efficiency of the HVAC system can save significant energy, increase thermal comfort, and contribute to improved indoor environmental quality (IEQ) [5]. Artificial intelligence (AI) was founded as an academic discipline in 1956. In contrast to human intelligence, AI demonstrates machine intelligence and imitates human behaviors through mathematical coding and mechanical works. In 1997, an AI program known as Deep Blue defeated the reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov [6]. It was the first time that the chess-playing computer performed better than a human. That moment was a turning point in the development of AI that enabled AI to be utilized more in a wider range of applications.

In this study, how AI could improve the performance of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems was investigated. A total of 783 articles, which were related to AI research and its application on HVAC systems, was collected from three databases, including the Science Direct on Line (SDOL), IEEE Xplore (IEL Online), and MDPI. The MDPI database is a publisher of open access journals. Following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) method [7] for reporting, systematic review, and meta-analysis, the collected articles were screened, and only 97 full-text articles met the requirements. All of the selected articles regard theoretical work and practical experiments about HVAC control. Detailed information of these articles, including the study cases, AI tools, or developments, and the improved performance of HVAC systems, are presented in Section 2 and summarized in Table 1. Among the 18 developed AI tools, only two methodologies have become mainstream elements of HVAC controls over the past 20 years, which are the forecasting and optimization and the predictive controls. These two main methodologies will be discussed in Section 3.

Table 1.

Artificial intelligence (AI) developments for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems and the obtained key results.

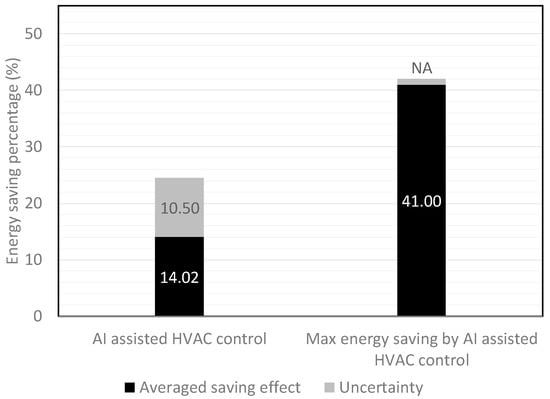

Even though the development of AI tools for HVAC systems is more than two decades old, the performance of HVAC systems controlled by AI tools has been unsatisfactory overall. Their energy savings, energy consumption, precision of heating and cooling based on load forecasting, and the predictive ability of the predictive controls, will be discussed in Section 4. Based on [8], from 1976 to 2014, the average energy savings of HVAC systems by applying the scheduling control technique reached 14.07%. The maximum energy savings of HVAC systems was 46.9% after applying smart sensors for smart air conditioners in 2014 [9]. However, from 1997 to 2018, the average energy savings of HVAC systems using AI tools reached 14.02%. The maximum energy savings when applying case-based reasoning (CBR) controlling tools for the HVAC systems in an office building was only 41% in 2014. Therefore, the energy savings of HVAC systems after applying AI tools was less than that of traditional energy management system (EMS) controlling techniques.

This study will be conducted in three parts, including (1) problem formulation and the hypothesis, (2) simulations and verification, and (3) confirmatory experiments. The first part, problem formulation and the hypothesis, will analyze the problem of HVAC systems using AI tools having less accuracy of forecasting, or and a prediction of the tools that result in poor energy savings is hypothesized. If forecast accuracies could be improved and prediction errors could be reduced, the energy savings of HVAC systems would improve. From the 35 collected articles with information regarding sensor specifications, the literature states that the existing sensors are for feedback control, not prediction, and therefore lack the capability to provide priori information notice (PIN). Hence, an innovative PIN sensor design and more precise predictive control is presented in this study as the solution to increase the energy savings of HVAC systems.

The second part of the study covers the simulation and verification of the energy-saving hypothesis and PIN sensor design through numerical simulation. Through numerical simulation, the calculated energy savings of an HVAC system using a PIN sensor will be provided. The third part consists of the confirmatory experiment where the designed PIN sensors are utilized under the various operating conditions of an HVAC system in an environmentally controlled room to measure energy consumption. The energy consumption of the HVAC system utilizing the PIN sensors and AI tools will be compared with those employing the proportional–integral–differential (PID) controllers, and the simulation results are analyzed to give evidence of the hypothesis presented in this study.

2. AI Developments and the Applications for HVAC Systems

In this study, keywords including AI, machine learning, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning, were utilized to conduct a paper survey from the Science Direct on Line (SDOL), IEEE Xplore (IEL Online), and MDPI databases. Initially, 737 papers were found from SDOL fitting the criteria of our paper survey, while 34 were found from IEEE Xplore, and 12 were found from MDPI. After further review, articles that were not related to HVAC control or methods to enhance performance were separated out. A total of 79 articles fit the requirements of either (1) describing the applying factory; (2) developing innovative AI tools and their use involving HVAC control; and (3) depictions describing the overall performance of an HVAC system after applying AI control tools. These articles were chosen for further exploration.

2.1. Study Case

The published year, HVAC system, developed AI technology, and key results of the collected 79 articles are listed in Table 1.

2.2. Developed AI Tools

In the second column of Table 1, there are 18 AI tools for HVAC systems. Among them, the most well-known AI tools are neuro networks (NN), including artificial neuro networks (ANN), recurrent neuro networks (RNN), spiking neuro networks (SNN), and wavelet ANN [15,16,19,22,23,24,27,29,34,35,37,39,40,44,51,52,53,59,60,64,76,79,81,82,85,87,98,99,100,102]. ANN is based on the nervous system, the human brain architecture, and the learning processes. A set of interconnected neurons can be separated into three layers, which are composed of input, output, and hidden layers. The HVAC system inputs, network weights, and the transfer functions of the network lead to the output of ANN. The ANN controller doesn’t need to identify the control model. The weight coefficient can be regulated to minimize the costs. ANN can simulate the working procedure of the human brain; therefore, it has the capability of having insight into a complex system. However, the brain-like controller has disadvantages due to having to take a lot of time for off-line training as well as requiring a large amount of data for the system to make quality predictions.

The second AI tool is used for the predictive control functions of ANN: fuzzy or model-based predictive control (MPC) [32,42,47,48,50,65,72,75,87,92,94,101,103,104]. Predictive control provides feedback of the results of the prediction to the system to allow for the adjustment of a system’s control parameters. The predictive feedback system is different from previous control systems due to the design of the feedback sensor. Collotta etc. created a non-linear autoregressive neural network auto regressive external type (NNARX-type) structure in 2014 for indoor temperature prediction [75]. In addition to enhancing the control performance, the signal of a predictive control system could be discontinuous for a non-linear system. This is different from the continuous signals that are needed for a linear system managed by a traditional PID controller, which is based on the Laplace transform and linear transfer functions. The insight ability of the ANN is similar to the human insight process, and is a smart way to improve the performance of a non-linear system commanded by predictive control.

The third type of AI tool is known as distributed AI and the multi-agent system (MAS) [20,26,31,57,58,62,66,72,73,83]. In addition to strengthening the entire performance of a system using ANN or predictive control, the subsystems, sensors, and actuators of an HVAC system are able to communicate and interact with each other and become an even more intelligent system through the use of MAS.

The fourth type of AI tool is what is known as the genetic algorithm (GA) method, which is based on biological evolution theory [14,45,54,59,61,63,74,82,93]. The GA method utilizes global non-derivative-based optimization to tune the set points of HVAC systems and meet the thermal comfort requirements without the use of a mathematical model of the system. However, the problem with the GA method is that it requires massive calculations and long run times. Therefore, the GA method might be inappropriate for the real-time operation of an HVAC system.

The fifth type of AI tools is employed for fuzzy control [21,32,33,46,51,59,102], support vector machines (SVM), and R [28,30,38,56,79,82,89]. These two AI tools have the same amount of published articles. A fuzzy logic controller (FLC) is similar to human reasoning and can be used to control a complex system by using the rules of the IF–THEN algorithm. The utilization of fuzzy logic grades and rules yields a low real-time response speed. This situation limits the application of the FLC onto HVAC systems. However, SVM and R could be used in conjunction with the FLC for data classification by finding the hard margins of various data sets to determine the proper control methodologies, modeling, or regression for decision making. This method is used mainly for analyzing huge amounts of data, modeling, and decision making, but is rarely used for HVAC system applications.

The seventh AI tools are model-based controls [10,17,18,69,91] and deep learning (DL, or reinforced learning) [36,49,88,97,98]. The model-based control models, when used with the SVM and R tools, collect and analyze data utilizing the distributed AI tool, and communicate and interact with the MAS tool. The advantage of model-based control is its predictive strategy and high capability of observation. However, the model-based control is a feedback control methodology that can only be applied to a time-independent system. It can’t solve problems within a non-linear time-variable system. A deep learning tool could determine a control strategy according to a system’s present conditions and information from previous cases through a learning process without the use of modeling. Deep learning is one of the broader machine learning methods, which is based on learning data representations, as opposed to following task-specific algorithms. The learning types are supervised, semi-supervised, or unsupervised. For an HVAC system, deep learning is a novel methodology to achieve more intelligent control.

The knowledge-based system (KBS) [11,12,13,43] is similar to the DL tool. However, the difference between them is that the DL tool is for controlling the system, and KBS is used for building various SVM and R knowledge databases. KBS could provide an optimal control strategy for various HVAC systems through the expert system. KBS and DL are mostly used for problem-solving procedures and to support human learning, decision making, and actions. Another key tool is case-based reasoning (CBR) [78]. However, there are not many published articles regarding this. CBR is able to analyze a control strategy and provide the most optimal one in conjunction with KBS or model-based control in certain cases. Nevertheless, KBS, DL, and CBR tools all need a large amount of data to learn from, and will require a lot of time to collect the control data, which will increase initial installation costs.

In addition, there are some other AI tools worth mentioning, which include: particle swarm optimization (PSO) [35,77,80] and the artificial fish swarm algorithm (AFSA) [90] for optimizing control strategies, the hidden Markov model (HMM) [70,71,89] for modeling, radial basis function (RBF) [67,68] for data collecting and analyzing, data combining technology [94,95], k-nearest neighbor (KNN) [89] for analyzing the closest data attribute, and the autoregressive exogenous (ARX) technique [65] for regression analysis with an external input and feedback control system.

2.3. AI Applications for HVAC Systems

The control methodologies of AI development can be observed by comparing columns one and two of Table 1, which outline the AI tools and related HVAC systems, respectively. There are four main HVAC system applications for AI tools, including (1) medium to large-scale utilities for commercial buildings [10,13,17,20,22,24,27,29,35,43,44,53,57,63,64,66,71,72,73,76,78,80,82,84,87,91,96,100,105], (2) air conditioners or chillers for residential buildings [11,15,18,19,21,36,37,38,39,42,51,52,60,61,62,65,67,68,69,70,72,75,79,83,86,88,92,94,97,98,99,101,102], (3) air conditioning systems for composite buildings [25,28,30,34,40,45,50,54,56,58,59,74,77,81,85,90,93,95,103,104], and (4) specific systems, such as a greenhouse, a regenerating power system, a power system, etc. [12,14,16,23,26].

The use of AI tools applied onto commercial and residential buildings will be discussed, due to the different occupant behavior patterns between the two building types. The occupants of commercial buildings operate within the confines of working in the numerous companies within a commercial building with a fixed office schedule, and therefore have more predictive air-conditioning demands. The HVAC systems of most commercial buildings are operated by professional energy managers under certain routines and energy-saving targets. Yet, the occupants of residential buildings, being residents, have different air-conditioning behaviors and demands. In general, the HVAC systems of most residential buildings are not operated by professional energy managers.

As mentioned in the previous section, ANN + fuzzy tools are the most widely utilized AI tools for commercial and residential buildings. The adoption ratios for these two types of buildings are 34.5% (10/29) and 24.2% (8/33), respectively. The ANN tool can imitate the operating model of the human brain to implement complex control strategies by learning and analyzing large amounts of data. This is suitable for commercial buildings due to the predictive nature of the occupants. Unfortunately, the ANN tool is not suitable for use in residential buildings. The ANN tool combined with DL, reinforced learning, or deep reinforcement learning (DFL) equips the system with the capability of feature extraction to analyze data and make control decisions, which replaces the need for a professional energy manager.

For commercial buildings, CBR and KBS tools operate alongside ANN + fuzzy tools. CBR and KBS tools can practice model base control and forecast several conditions, including weather, occupancy, and energy consumption, optimize control set points, improve the energy efficiency of an HVAC system, and ensure thermal comfort [13,22,24,27,29,35,43,44,53,64,76,78,84,100,105]. Based on the cases utilizing ANN, CBR, and KBS tools, the ability to make predictions is the most significant function of these AI tools. For residential buildings, DL, distributed AI, and MAS tools function alongside ANN + fuzzy tools. If the fundamental devices of HVAC systems are equipped with distributed AI tools for saving energy and ensuring the thermal comfort, and are able to interact with each other through an MAS tool, then predictive control and the prediction of future environmental conditions for enhancing a system’s overall performance could be achieved.

Finally, the most recent development of AI tools applied onto composite buildings is predictive control [50,103,104], which improves the control performance of an HVAC system by having the ability to make predictions. Composite building systems are a mix of residential commercial building systems.

3. Theoretical Analysis of AI Assisted HVAC Control

In this section, the control performance differences between typical HVAC controls and AI-assisted HVAC controls are analyzed quantitatively. The control outputs were calculated by the common analytic solutions of the AI-assisted HVAC controls in Table 1, which were then compared with those of the on–off and proportional–differential–integral (PID) controls.

3.1. Typical HVAC Control

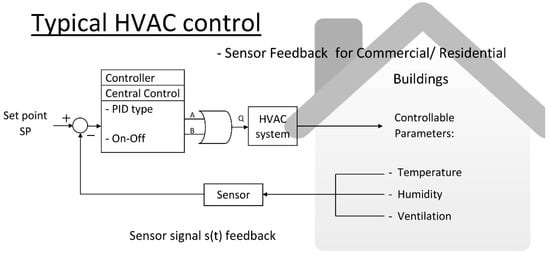

Typical HVAC controls for residential and commercial buildings utilize on–off and PID control algorithms [106] in addition to sensor feedback controls to have the ability to control parameters such as a system’s temperature, humidity, and ventilation. The controllable structure is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Typical HVAC controls for residential or commercial buildings.

The control block diagram in Figure 1 runs PID or an on–off algorithm by comparing the set point values and sensor feedback values, and then providing the subsequent output control signals to an HVAC system.

The on–off control output values are calculated according to the following Equation:

where is the step function corresponding to the difference reading of the sensor feedback, S(t), and the set point, SP, of an HVAC system. If the difference value is larger than the designed threshold value, the value of is one. If the difference value of S(t) and SP is within the standard variation of S(t), the value of is zero. The modification of on–off control is that, instead of being zero, the value of is located within the range of 0.5~0.7 when the difference value is within the standard variation of S(t). This is the so-called floating control to avoid the large oscillation of a control signal of the HVAC system. However, no matter how the typical on–off control or floating control is utilized, the final control signal is determined by the difference of S(t) and SP, as shown in Equation (1).

The output of PID control, as shown in Figure 1, is calculated according to the following equation:

where is the proportional constant, is the integral constant, and is the differential constant. The differentiation between is able to predict the controlling oscillation of the next stage and eliminate it within a short period. The integration of is capable of providing a stable output of PID control and reaching the final state of after a longer period.

3.2. AI-Assisted HVAC Control

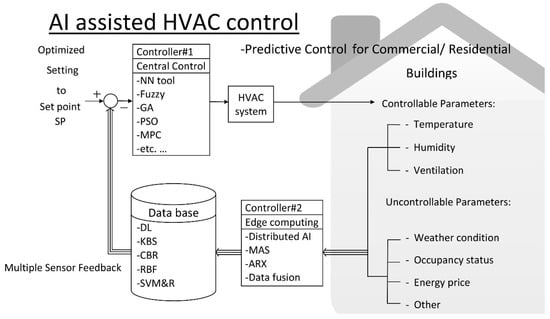

The block diagram of AI-assisted HVAC control resulting from the collected articles is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

AI-assisted HVAC controls for residential and commercial buildings.

The core of AI assisted HVAC control is the ANN tool illustrated as controller #1 in Figure 2. The output, y, of the ANN tool is produced through many processes, or neurons, and these neurons interconnect with each other by multiplying with the weights, ω, as shown in the following equation [9,15,16,22,23,24,27,29,44,47,51,52,64,75,81,85,87,99]:

where , , … and are the weighting coefficients, and g is a non-linear activation function, which is usually a step or a sigmoid function, as illustrated by the following equation:

The neuron output, y, is unidirectional both for feedback or feedforward control. The ANN tool is skilled at solving data-intensive problems within the categories of pattern classification, clustering, function approximation, prediction, optimization, content retrieval, and process control. It is similar to the human ability to make a single decision based on multiple inputs. Therefore, the main characteristic of AI-assisted HVAC control is its multiple sensor feedback, as shown in Figure 2. The multiple feedback sensor collects several sensor inputs, including controllable and uncontrollable parameters, to build a database. AI tools are not only in the central control port, as shown in controller #1 of Figure 2, but they are also applied in the sensor port, as shown in controller #2 of Figure 2, for more intelligent control.

The most utilized intelligent control functions are the optimized setting and predictive control functions, as shown in Figure 2. First, the optimized setting function utilizes the KBS [11,12,13,43,67,68,84] or CBR [34,78,105] tools from the database block to determine the set point (SP). The similarity index (SI) is employed during the calculation process, as shown in the following equation:

where and are the neuro outputs of the variable i for the control and past case, respectively. is the mean difference of the variable i in the database. The function f maps the control case to the whole case difference. Based on SI, the global similarity (GS) is calculated according to the following equation:

where n is the number of the controlled case and is the weighting coefficient.

The proportion of the prediction from the past case j is:

where is the sum of the global similarities between the selected m cases. Then, the optimized setting point (SPopm) can be determined by the following equation:

where is the set point of past case j. The optimized set point is determined from the built database, including the previous controllable and uncontrollable parameters, and the desired SP value.

In addition to the optimized settings, other intelligent control functions are the predictive controls, which utilize the ANN + fuzzy tool as the central controller, as shown in controller #1 of Figure 2. This tool employs an IF–THEN algorithm to enhance the control performance by predicting the likelihood of future errors effectively and providing proper feedback. The SVM and R tool [28,30,38,56,79,82,89] and autoregressive with exogenous terms (ARX) tool [65] are also suitable for central and edge computing ports, respectively.

The first step of predictive control is to determine probability. After comparing the calculation methods of several articles, the suggested equation is shown in the following:

where i indicates the ith sensor for detecting controllable or uncontrollable parameters. is the ith sensor value, is the pheromone intensity, and and are the experience parameters. In addition to the probability value, a Guess value is also necessary for predictive control. It is calculated after the ANN runs [9,15,16,22,23,24,27,29,44,47,51,52,64,75,81,85,87,99] according to the following equation:

where , , … and are the weighting coefficients, and g is the non-linear activation function, as illustrated above. The following equation is able to predict the sensor output of the next stage.

where a is the momentum parameter, b is the self-influence parameter, and c is the measure insight. R1 and R2 are the random numbers within [0,1] for predictive control.

3.3. Control Performance Index

The Harris index (H) and normalized Harris index (NHI) [107,108] are utilized for evaluating the performances of typical and AI-assisted HVAC control outputs, as shown in the following equations:

where . The Harris index compares the variations between the initial control y(0) and y(t + 1). There are several articles discussing the effect of rising time, settling time, and overshooting [32] on the control performance of the linear system. However, the Harris index and NHI are able to assess the performance of linear, non-linear, feedforward, and feedback control systems [109], as well as thermal comfort and energy efficiency, etc.

NHI = 1 − 1/H

4. Results and Discussions

In this study, the Harris index and NHI are employed to estimate the performance of HVAC systems in Table 1 managed by On–Off, PID, and AI-assisted control. The sensor signal outputs of the On–Off and PID controls, as shown in Equations (1) and (2), have a positive linear relationship with the Harris index. Therefore, the sensor types mentioned in the articles in Table 2 will be indicated and, then, the sensor errors will be calculated.

Table 2.

Different sensors employed by AI-assisted HVAC control.

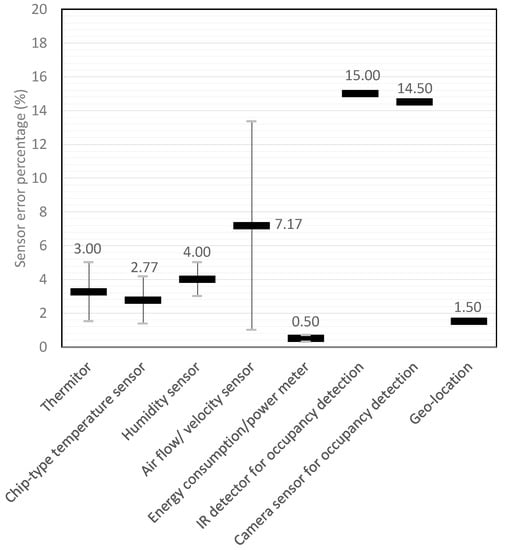

In addition, one commercialized product, Ambi Climate, with a geolocation sensor and applied sensors for the academic cases are analyzed in Table 2. The sensor types and the individual sensor errors are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Sensor errors with respect to different type of sensors employed by AI-assisted HVAC control.

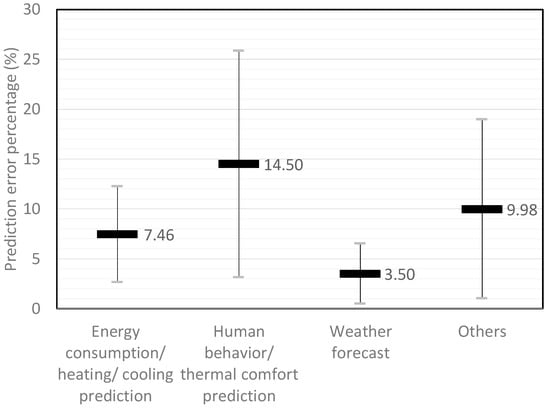

The performance indexes of On–Off and PID controls are calculated by the sensor errors, as shown in Figure 3. However, instead of sensor errors, the Harris indexes of the optimized settings and predictive controls are determined by the predictive errors, as shown in Equations (8) and (11). The collected prediction or forecast errors of AI-assisted HVAC controls in Table 1 are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Prediction or forecast errors of AI-assisted HVAC control.

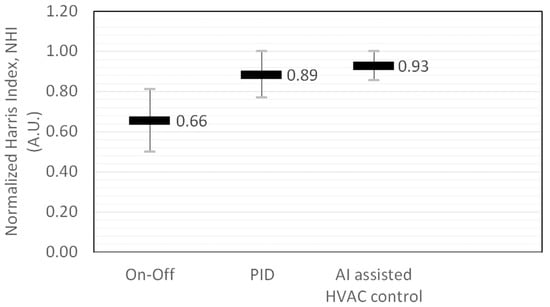

For the On–Off control variables of and , both are directly proportional to any sensor errors. Therefore, the calculated H is equal to one, and it becomes the comparison reference. For PID control, when the damping ratio is located in a lower damping ratio range from 0.5 to 1.5, the is able to reduce sensor errors by up to 30%, which will in turn enhance the H index value. Due to the reduction of the steady-state error by the integral (KI) control, a PID control has a better control ability than that of an On–Off control system, when the damping ratio is located within normal to lower value ranges. For higher damping ratio systems, the initial stage , the final stage , and the NHI value of the PID control will fluctuate due to variations of the proportional (KP) and differential (KD) control within a range of [0.2–0.69]. For AI-assisted HVAC control, the is estimated from the sensor output S(t+1), and the assumption is that the NHI is equal to one, as illustrated in Equations (12) and (13). However, the prediction or forecast errors of the AI controls fluctuate at certain ranges and cause variations of the NHI. This occurs particularly when the AI control utilizes human behavior algorithms or thermal comfort prediction algorithms, and the NHI is even lower than that of the PID control. The NHIs of On–Off, PID, and AI-assisted HVAC controls are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Normalized Harris index (NHI) of different kinds of HVAC controls and the expected performance improvements for energy savings.

The NHI is utilized to evaluate the performance of the control tools, and especially focuses on the energy-saving percentages, because of its capability to estimate the performance of linear and non-linear control systems. In Table 1, there are only 24 cases [11,12,14,19,21,44,50,57,58,62,63,72,73,83,84,92,93,94,97,98,101,103,105] that have references to the energy-saving percentages of AI-assisted HVAC controls. The average energy saving percentages of these 24 cases are shown in Figure 6, and a maximum energy savings of 41% is achieved by decision making through the MAS and CBR tools.

Figure 6.

The average energy savings of the 24 cases and the maximum energy savings achieved by AI-assisted HVAC control.

In Figure 6, the average energy savings percentage when using AI-assisted HVAC control is 14.02%. Of the 24 cases, 83% were comprised of On–Off control, and 17% were comprised of PID control. Based on the NHI, the estimated average energy savings percentage, variations in energy savings, and the maximum energy savings of AI-assisted HVAC control are 14.4%, 22.32%, and 44.04%, respectively. Comparing these results with the experimental data of 14.02%, 24.52%, and 41.0% in Figure 6, the errors are 3%, 9%, and 7%, respectively.

5. Conclusions

The presented NHI in this research can be used to evaluate the performance of AI-assisted HVAC control effectively, especially for non-linear control systems assisted by the optimized setting with CBR or KBS tools, or predictive control with the distributed AI and fuzzy algorithm. In order to calculate the NHI, the following hypotheses are made:

- (1)

- If the prediction/forecast accuracy could reach 3.5%, which approaches the thresholds of weather forecast accuracy and the accuracies of several types of sensors, including the thermistor, chip type temperature sensor, and humidity sensor, the performance of AI-assisted HVAC control will be enhanced. When compared with the On–Off and PID control strategies, the performance of the AI-assisted HVAC control had an increase of 57.0% and 44.64%, respectively. The increased energy saving percentages are above the average, and even above the maximum energy savings that were found in any of the published articles from 1997 to 2018.

- (2)

- In this study, the lower accuracy of the prediction tools and the resulting poor energy savings of HVAC systems are hypothesized. This hypothesis is from the collected articles, and forms the qualitative research in this paper. In the future, based on the hypothesis, the performance improvement of AI-assisted HVAC control will depend on the prediction accuracy of the sensors, which will be evidenced through the numerical simulation in Part 2 and the confirming experiments in Part 3.

- (3)

- The existing sensors are designed for accurate sensing, but not for accurate prediction, and this causes an unmet demand of the sensors. Improved sensors for AI-assisted HVAC controls should be able to provide the ability of more accurate prediction. Based on Bayes’ theorem, accurate prediction depends on the conditional probability. The priori probability can be utilized to determine the posterior possibility, and the consistent prediction can be achieved by aggregation. The priori information notice (PIN) design for sensors are provided in this study to decrease the prediction errors to as low as 3.5% or less. The details of the PIN sensor will be discussed in Part 2 of the serial research.

Author Contributions

D.L. initiated the idea, provided the draft, and completed the theoretical calculation. C.-C.C. completed the writing, translation, and revision of the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology, R.O.C. through the contract MOST 106-2622-E-027-025-CC2 and 107-2622-E-027-001-CC2, and the industrial cooperating project between the National Taipei University of Technology (NTUT) and Hitachi Taiwan Company.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shukla, A.; Sharma, A. Sustainability through Energy-Efficient Buildings; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781138066755. [Google Scholar]

- Martinopoulos, G.; Serasidou, A.; Antoniadou, P.; Papadopoulos, A.M. Building Integrated Shading and Building Applied Photovoltaic System Assessment in the Energy Performance and Thermal Comfort of Office Buildings. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinopoulos, G.; Papakostas, K.T.; Papadopoulos, A.M. A comparative review of heating systems in EU countries, based on efficiency and fuel cost. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yan, H.; Lam, J.C. Thermal comfort and building energy consumption implications—A review. Appl. Energy 2014, 115, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belic, F.; Hocenski, Z.; Sliskovic, D. HVAC Control Methods—A review. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC), Cheile Gradistei, Romania, 14–16 October 2015; pp. 679–686. [Google Scholar]

- WikipediaArtificial Intelligence. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_intelligence_1 (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- Swartz, M.K. A look back at research synthesis. J. Pediatr. Heal. Care 2010, 24, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Cheng, C.-C. Energy savings by energy management systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Jakeman, A.J.; Norton, J.P. Artificial Intelligence techniques: An introduction to their use for modelling environmental systems. Math. Comput. Simul. 2008, 78, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bann, J.J.; Irisarri, G.D.; Mokhtari, S.; Kirschen, D.S.; Miller, B.N. Integrating AI applications in an energy management system. IEEE Expert 1997, 12, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Mehta, P. Artificial intelligence and networking in integrated building management systems. Autom. Constr. 1997, 6, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigrimis, N.; Anastasiou, A.; Vogli, V. An open system for the management and control of greenhouses. In Proceedings of the IFAC Proceedings Volumes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 31, pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Rosano, F.; Valverde, N.K. Knowledge-based systems for energy conservation programs. Expert Syst. Appl. 1998, 14, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jin, X. Model-based optimal control of VAV air-conditioning system using genetic algorithm. Build. Environ. 2000, 35, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.; Florides, G.; Neocleous, C.; Schizas, C. Estimation of daily heating and cooling loads using artificial Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the CLIMA 2000 International Conference, Naples, Italy, 15–18 September 2001; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Artificial neural networks in renewable energy systems applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2001, 5, 373–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummert, M.; André, P.; Nicolas, J. Optimal heating control in a passive solar commercial building. Sol. Energy 2000, 69, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intille, S.S. Designing a home of the future. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2002, 1, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalakakou, G.; Santamouris, M.; Tsangrassoulis, A. On the energy consumption in residential buildings. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penya, Y.K. Last-generation applied artificial intelligence for energy management in building automation. In Proceedings of the IFAC Proceedings Volumes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 36, pp. 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotsa, D. Comparison of the performance of fuzzy controllers for the management of the indoor environment. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.H.; Yeo, M.S.; Kim, K.W. Application of artificial neural network to predict the optimal start time for heating system in building. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 2791–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.C.; Tsao, T.P. Application of fuzzy neural networks and artificial intelligence for load forecasting. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2004, 70, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Rivard, H.; Zmeureanu, R. On-line building energy prediction using adaptive artificial neural networks. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.W.; Li, H.; Wang, S.W. Intelligent building research: A review. Autom. Constr. 2005, 14, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozer, M. The adaptive house. In Proceedings of the the IEE Seminar on Intelligent Building Environments, Colchester, UK, 28 June 2005; pp. 39–79. [Google Scholar]

- González, P.A.; Zamarreño, J.M. Prediction of hourly energy consumption in buildings based on a feedback artificial neural network. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Cao, C.; Lee, S.E. Applying support vector machines to predict building energy consumption in tropical region. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Steemers, K. A method of formulating energy load profile for domestic buildings in the UK. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.R.; Arif, M. Electric load forecasting using support vector machines optimized by genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Multitopic Conference, Islamabad, Pakistan, 23–24 December 2006; pp. 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjiski, M.; Sgurev, V.; Boishina, V. Multi agent intelligent control of centralized HVAC systems. In Proceedings of the IFAC Proceedings Volumes; IFAC: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Terziyska, M.; Todorov, Y.; Petrov, M. Fuzzy-Neural model predictive control of a building heating system. In Proceedings of the IFAC Proceedings Volumes; IFAC: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 39, pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Saridakis, G.; Pouliezos, A.; Stavrakakis, G.S. Design and installation of an advanced EIBTM fuzzy indoor comfort controller using MatlabTM. Energy Build. 2006, 38, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Lian, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, X. Cooling-load prediction by the combination of rough set theory and an artificial neural-network based on data-fusion technique. Appl. Energy 2006, 83, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaraj, P.; Rajasekaran, V. Short term hourly load forecasting using combined artificial Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Multimedia Applications (ICCIMA 2007), Sivakasi, Tamil Nadu, India, 13–15 December 2007; pp. 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dalamagkidis, K.; Kolokotsa, D.; Kalaitzakis, K.; Stavrakakis, G.S. Reinforcement learning for energy conservation and comfort in buildings. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2686–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.H.; Fiorelli, F.A.S. Comparison between detailed model simulation and artificial neural network for forecasting building energy consumption. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalina, T.; Virgone, J.; Blanco, E. Development and validation of regression models to predict monthly heating demand for residential buildings. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Sakawa, M.; Ishimaru, K.; Ushiro, S.; Shibano, T. Heat load prediction through recurrent neural network in district heating and cooling systems. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Singapore, 12–15 October 2008; pp. 1401–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.A.; Hoogenboom, G.; McClendon, R.W. Artificial neural networks for automated year-round temperature prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 68, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Sun, F.; Zhou, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, N. Performance prediction of wet cooling tower using artificial neural network under cross-wind conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2009, 48, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wang, S.; Xu, X. A robust model predictive control strategy for improving the control performance of air-conditioning systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 2650–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, M.J.; Kastner, W. A knowledge base for energy-efficient smart homes. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Energy Conference and Exhibition, Manama, Bahrain, 18–22 December 2010; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Ren, Q. Optimization for the Chilled Water System of HVAC Systems in an Intelligent Building. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Computational and Information Sciences, Chengdu, China, 17–19 December 2010; pp. 889–891. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, Z.A.; Morais, H.; Khodr, H. Intelligent multi-player smart grid management considering distributed energy resources and demand response. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES General Meeting, PES 2010, Providence, RI, USA, 25–29 July 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Saridakis, G.; Dalamagkidis, K.; Dolianitis, S.; Kaliakatsos, I. Development of an intelligent indoor environment and energy management system for greenhouses. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombayci, Ö.A. The prediction of heating energy consumption in a model house by using artificial neural networks in Denizli-Turkey. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2010, 41, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardin, L.; Marechal, F.; Dubuis, M.; Calame-Darbellay, N.; Favrat, D. EnerGis: A geographical information based system for the evaluation of integrated energy conversion systems in urban areas. Energy 2010, 35, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qela, B.; Mouftah, H. An adaptable system for energy management in intelligent buildings. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Measurement Systems and Applications Proceedings, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 19–21 September 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, B.; Eynard, J.; Grieu, S.; Polit, M. Hybrid PID-fuzzy control scheme for managing energy resources in buildings. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 5068–5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, T.R.; Rajput, S.P.S. An effectiveness model for an indirect evaporative cooling (IEC) system: Comparison of artificial neural networks (ANN), adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) and fuzzy inference system (FIS) approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W.; Jung, S.K.; Kim, Y.; Han, S.H. Comparative study of artificial intelligence-based building thermal control methods—Application of fuzzy, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system, and artificial neural network. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 2422–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynard, J.; Grieu, S.; Polit, M. Wavelet-based multi-resolution analysis and artificial neural networks for forecasting temperature and thermal power consumption. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2011, 24, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahedi, G.; Ardehali, M.M. Genetic algorithm-based fuzzy-pid control methodologies for enhancement of energy efficiency of a dynamic energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Korres, N.E.; Ploennigs, J.; Elhadi, H.; Menzel, K. Mining building performance data for energy-efficient operation. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2011, 25, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.K.W.; Li, D.H.W.; Liu, D.; Lam, J.C. Future trends of building heating and cooling loads and energy consumption in different climates. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cho, W.-H.; Jeong, Y.; Song, O. Intelligent energy management system for smart offices. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 13–16 January 2012; pp. 668–669. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, J.; Kim, Y.; Hwang, Z.; Park, S. An intelligent cloud-based energy management system using machine to machine communications in future energy environments. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 13–16 January 2012; pp. 664–665. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Chen, L.; Mohammadzaheri, M.; Hu, E. A new zone temperature predictive modeling for energy saving in buildings. Procedia Eng. 2012, 49, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvuglia, A.; Messineo, A. Using recurrent artificial neural networks to forecast household electricity consumption. Energy Procedia 2012, 14, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.M.; Silva, S.M.; Ruano, A.E. Model based predictive control of HVAC systems for human thermal comfort and energy consumption minimisation. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2012, 45, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.; Kwak, J.Y.; Kavulya, G.; Jazizadeh, F.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Varakantham, P.; Tambe, M. Coordinating occupant behavior for building energy and comfort management using multi-agent systems. Autom. Constr. 2012, 22, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čongradac, V.; Kulić, F. Recognition of the importance of using artificial neural networks and genetic algorithms to optimize chiller operation. Energy Build. 2012, 47, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahedi, G.; Ardehali, M.M. Wavelet based artificial neural network applied for energy efficiency enhancement of decoupled HVAC system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 54, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.; Luck, R.; Mago, P.J.; Cho, H. Building hourly thermal load prediction using an indexed ARX model. Energy Build. 2012, 54, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wim, Z.; Timilehin, L.; Kennedy, A. Towards multi-agent systems in building automation and control for improved occupant comfort and energy efficiency—State of the art, challenges. In Proceedings of the 2013 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Engineering Applications, Zhangjiajie, China, 6–7 November 2013; pp. 718–722. [Google Scholar]

- Ciabattoni, L.; Grisostomi, M.; Ippoliti, G.; Longhi, S. Neural networks based home energy management system in residential PV scenario. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 39th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Tampa, FL, USA, 16–21 June 2013; pp. 1721–1726. [Google Scholar]

- Ciabattoni, L.; Ippoliti, G.; Benini, A.; Longhi, S.; Pirro, M. Design of a home energy management system by online neural networks. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2013, 46, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Morais, H.; Faria, P.; Vale, Z.; Ramos, C. SCADA house intelligent management for energy efficiency analysis in domestic consumers. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE PES Conference on Innovative Smart Grid Technologies, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 15–17 April 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Thottan, M.; Feather, F. Designing customized energy services based on disaggregation of heating usage. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 15–17 April 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic, M.; Amft, O. Recognizing energy-related activities using sensors commonly installed in office buildings. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 19, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, L. Development of multi-agent system for building energy and comfort management based on occupant behaviors. Energy Build. 2013, 56, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Aiello, M. Energy intelligent buildings based on user activity: A survey. Energy Build. 2013, 56, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabali, A.; Ghofrani, M.; Etezadi-Amoli, M.; Fadali, M.S.; Baghzouz, Y. Genetic-algorithm-based optimization approach for energy management. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2013, 28, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collotta, M.; Messineo, A.; Nicolosi, G.; Pau, G. A dynamic fuzzy controller to meet thermal comfort by using neural network forecasted parameters as the input. Energies 2014, 7, 4727–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, R.; Rodríguez, F.; Castilla, M.; Arahal, M.R. A prediction model based on neural networks for the energy consumption of a bioclimatic building. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, P.; Patidar, N.P.; Nema, R.K. Determination of reliability constrained optimal resource mix for an autonomous hybrid power system using Particle Swarm Optimization. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfet, D.; Corsi, M.; Choinière, D.; Arkhipova, E. Development of an energy prediction tool for commercial buildings using case-based reasoning. Energy Build. 2014, 81, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.S.; Bui, D.K. Modeling heating and cooling loads by artificial intelligence for energy-efficient building design. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zonkoly, A. Intelligent energy management of optimally located renewable energy systems incorporating PHEV. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 84, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Cardeira, C.; Calado, J.M.F. The daily and hourly energy consumption and load forecasting using artificial neural network method: A case study using a set of 93 households in Portugal. Energy Procedia 2014, 62, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumo, N. A review on the basics of building energy estimation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, I.; Li, H.; Rezgui, Y.; Yang, C.; Yuce, B.; Jayan, B. A modular optimisation model for reducing energy consumption in large scale building facilities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, T.G.; Kontopoulos, E.; Bassiliades, N.; Argyriou, J.; Bikakis, A.; Vrakas, D.; Vlahavas, I. Rule-based approaches for energy savings in an ambient intelligence environment. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2015, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, M.N.Q.; Galo, J.J.M.; De Almeida, L.A.L.; de C. Lima, A.C. Demand side management using artificial neural networks in a smart grid environment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W. Comparative performance analysis of the artificial-intelligence-based thermal control algorithms for the double-skin building. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 91, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazrak, A.; Leconte, A.; Chèze, D.; Fraisse, G.; Papillon, P.; Souyri, B. Numerical and experimental results of a novel and generic methodology for energy performance evaluation of thermal systems using renewable energies. Appl. Energy 2015, 158, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baz, W.; Tzscheutschler, P. Short-term smart learning electrical load prediction algorithm for home energy management systems. Appl. Energy 2015, 147, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.L.G.; Han, L.; Whittacker, N.; Bowring, N. A machine-learning based approach to model user occupancy and activity patterns for energy saving in buildings. In Proceedings of the 2015 Science and Information Conference, London, UK, 28–30 July 2015; pp. 474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Huang, J.H.; Xie, Z.J.; Littler, T. Modelling the benefits of smart energy scheduling in micro-grids. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 26–30 July 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Olatomiwa, L.; Mekhilef, S.; Ismail, M.S.; Moghavvemi, M. Energy management strategies in hybrid renewable energy systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salakij, S.; Yu, N.; Paolucci, S.; Antsaklis, P. Model-Based Predictive Control for building energy management. I: Energy modeling and optimal control. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, P.H.; Nor, N.B.M.; Nallagownden, P.; Elamvazuthi, I.; Ibrahim, T. Intelligent multi-objective control and management for smart energy efficient buildings. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 74, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aki, H.; Wakui, T.; Yokoyama, R. Development of a domestic hot water demand prediction model based on a bottom-up approach for residential energy management systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 108, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Ma, X. A hybrid forecasting approach applied in the electrical power system based on data preprocessing, optimization and artificial intelligence algorithms. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 10631–10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brøgger, M.; Wittchen, K.B. Estimating the energy-saving potential in national building stocks—A methodology review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Building HVAC Control. In Proceedings of the 2017 54th ACM/EDAC/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), Austin, TX, USA, 18–22 June 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Velswamy, K.; Huang, B. A long-short term memory recurrent neural network based reinforcement learning controller for office heating ventilation and air conditioning systems. Processes 2017, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- DiSanto, K.G.; DiSanto, S.G.; Monaro, R.M.; Saidel, M.A. Active demand side management for households in smart grids using optimization and artificial intelligence. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2018, 115, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.G.B.; Rueda, R.; Cuéllar, M.P.; Pegalajar, M.C. Energy consumption forecasting based on Elman neural networks with evolutive optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 92, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godina, R.; Rodrigues, E.M.G.; Pouresmaeil, E.; Matias, J.C.O.; Catal, J.P.S. Model predictive control home energy management and optimization strategy with demand response. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrooz, F.; Mariun, N.; Marhaban, M.H.; Radzi, M.A.M.; Ramli, A.R. Review of control techniques for HVAC systems—nonlinearity approaches based on Fuzzy cognitive maps. Energies 2018, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serale, G.; Fiorentini, M.; Capozzoli, A.; Bernardini, D.; Bemporad, A. Model predictive control (MPC) for enhancing building and HVAC system energy efficiency: Problem formulation, applications and opportunities. Energies 2018, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Bao, J. A novel distributed economic model predictive control approach for building air-conditioning systems in microgrids. Mathematics 2018, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Briones, A.; Prieto, J.; Prieta, F.D.L.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Corchado, J.M. Energy optimization using a case-based reasoning strategy. Sensors 2018, 18, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASHRAE. Fundamentals of HVAC Control Systems; I-P; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 9781933742915. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, T.J. Assessment of Control Loop Performance. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1989, 67, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.J.; Boudreau, F.; Macgregor, J.F. Performance assessment of multivariable feedback controllers. Automatica 1996, 32, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Feedforward and feedback control performance assessment for nonlinear systems. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambi-LabsAI-Enhanced Air Conditioning Comfort. Available online: https://www.ambiclimate.com/en/features/ (accessed on 5 November 2018).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).