Imprinting Technology in Electrochemical Biomimetic Sensors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Polymeric Materials

2.1. Organic Polymers

2.2. Hydrogels

2.3. Sol-Gel Materials

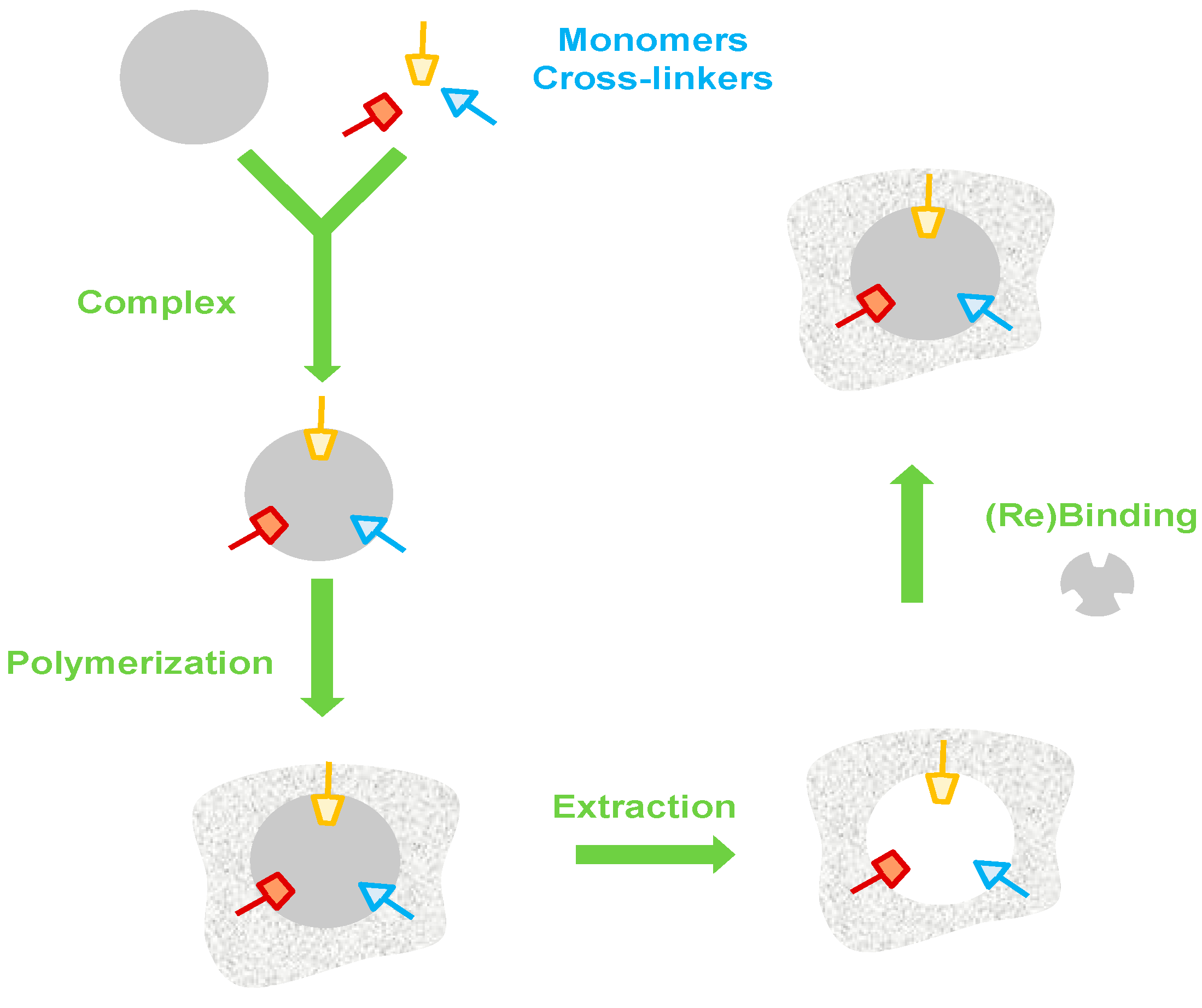

3. Imprinting Technology

3.1. Bulk Imprinting

3.2. Surface Imprinting

3.2.1. Microcontact Imprinting

3.2.2. Polymer-Brush Imprinting

3.2.3. Surface Grafting

3.2.4. Electropolymerization

3.3. Epitope Imprinting

4. Electrochemical Transduction

4.1. Voltammetry/Amperometry

4.2. Potentiometry

4.2.1. ISE Systems

4.2.2. FET Systems

4.3. Capacitance/Impedance

5. Labelling Methods

5.1. Label-Free MIP-Based Sensors

5.2. Labeling MIP-Based Sensors

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreira, F.T.C.; Dutra, R.A.F.; Noronha, J.P.C.; Cunha, A.L.; Sales, M.G.F. Artificial antibodies for troponin T by its imprinting on the surface of multiwalled carbon nanotubes: Its use as sensory surfaces. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 28, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, F.T.C.; Sharma, S.; Dutra, R.A.F.; Noronha, J.P.C.; Cass, A.E.G.; Sales, M.G.F. Smart plastic antibody material (SPAM) tailored on disposable screen printed electrodes for protein recognition: Application to myoglobin detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 45, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryscio, D.R.; Peppas, N.A. Critical review and perspective of macromolecularly imprinted polymers. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitcombe, M.J.; Chianella, I.; Larcombe, L.; Piletsky, S.A.; Noble, J.; Porter, R.; Horgan, A. The rational development of molecularly imprinted polymer-based sensors for protein detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1547–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scorrano, S.; Mergola, L.; Del Sole, R.; Vasapollo, G. Synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymers for amino acid derivates by using different functional monomers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellergren, B.; Ekberg, B.; Mosbach, K. Molecular imprinting of amino acid derivatives in macroporous polymers—Demonstration of substrate- and enantio-selectivity by chromatographic resolution of racemic mixtures of amino acid derivatives. J. Chromatogr. A 1985, 347, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-F.; Zhou, L.-M.; Liu, X.-L.; Wang, Q.-H.; Zhu, D.-Q. Novel polymer system for molecular imprinting polymer against amino acid derivatives. Chin. J. Chem. 2000, 18, 621–625. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, L.K.; Singh, M.; Singh, M. Biopolymeric receptor for peptide recognition by molecular imprinting approach-synthesis, characterization and application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 45, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiak, D.S.; Kofinas, P. Molecular imprinting of peptides and proteins in aqueous media. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 389, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachkov, A.; Minoura, N. Recognition of oxytocin and oxytocin-related peptides in aqueous media using a molecularly imprinted polymer synthesized by the epitope approach. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 889, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Mao, X.; Cao, S.; Yuan, X. Recognition of proteins and peptides: Rational development of molecular imprinting technology. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2010, 52, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunemori, H.; Araki, K.; Uezu, K.; Goto, M.; Furusaki, S. Surface imprinting polymers for the recognition of nucleotides. Bioseparation 2001, 10, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, N.; Ye, L.; Tang, H. Molecular imprinting for removing highly toxic organic pollutants. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzuriaga-Sánchez, R.J.; Khan, S.; Wong, A.; Picasso, G.; Pividori, M.I.; Sotomayor, M.D.P.T. Magnetically separable polymer (Mag-MIP) for selective analysis of biotin in food samples. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, A.H.; Almeida, S.A.A.; Sales, M.G.F.; Moreira, F.T.C. Sulfadiazine-potentiometric sensors for flow and batch determinations of sulfadiazine in drugs and biological fluids. Anal. Sci. 2009, 25, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, F.T.C.; Kamel, A.H.; Guerreiro, J.R.L.; Sales, M.G.F. Man-tailored biomimetic sensor of molecularly imprinted materials for the potentiometric measurement of oxytetracycline. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, W.J.; Yang, S.H.; Ali, F. Molecular imprinted polymers for separation science: A review of reviews. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.S.; Pietrzyk-Le, A.; D’Souza, F.; Kutner, W. Electrochemically synthesized polymers in molecular imprinting for chemical sensing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 3177–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, M.; Iwasawa, Y. Design of molecular-imprinting metal-complex catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2003, 199, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luliński, P. Molecularly imprinted polymers as the future drug delivery devices. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2013, 70, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uzun, L.; Turner, A.P.F. Molecularly-imprinted polymer sensors: Realizing their potential. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 76, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Mosbach, K. Molecular imprinting: Synthetic materials as substitutes for biological antibodies and receptors. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelet, C.; Peyrin, E. Recent developments in the HPLC enantiomeric separation using chiral selectors identified by a combinatorial strategy. J. Sep. Sci. 2006, 29, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral-Miranda, G.; Gidlund, M.; Sales, M.G.F. Backside-surface imprinting as a new strategy to generate specific plastic antibody materials. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, O.Y.F.; Piletsky, S.A.; Cullen, D.C. Fabrication of molecularly imprinted polymer microarray on a chip by mid-infrared laser pulse initiated polymerisation. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Multiepitope templates imprinted particles for the simultaneous capture of various target proteins. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 5621–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piletsky, S.A.; Piletska, E.V.; Chen, B.; Karim, K.; Weston, D.; Barrett, G.; Lowe, P.; Turner, A.P.F. Chemical grafting of molecularly imprinted homopolymers to the surface of microplates. Application of artificial adrenergic receptor in enzyme-linked assay for β-agonists determination. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 4381–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titirici, M.-M.; Sellergren, B. Thin molecularly imprinted polymer films via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piletsky, S.A.; Turner, A.P.F. Electrochemical sensors based on molecularly imprinted polymers. Electroanalysis 2002, 14, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Halsall, H.B.; Heineman, W.R. Electrochemical biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1747–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, G.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Imprinting of molecular recognition sites on nanostructures and its applications in chemosensors. Sensors 2008, 8, 8291–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Ren, L.; Zhao, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Lan, Y.; Roberts, M.F.; Chuang, J.H.; et al. A molecular-imprint nanosensor for ultrasensitive detection of proteins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, V.; Chikkaveeraiah, B.V.; Patel, V.; Gutkind, J.S.; Rusling, J.F. Ultrasensitive immunosensor for cancer biomarker proteins using gold nanoparticle film electrodes and multienzyme-particle amplification. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayes, A.G.; Whitcombe, M.J. Synthetic strategies for the generation of molecularly imprinted organic polymers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1742–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgreen, J.E.; Ozin, G.A. Controlling morphology and porosity to improve performance of molecularly imprinted sol-gel silica. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 911–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieplak, M.; Kutner, W. Artificial biosensors: How can molecular imprinting mimic biorecognition? Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff, G. Molecular imprinting in cross-linked materials with the aid of molecular templates—A way towards artificial antibodies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1812–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbach, K.; Ramström, O. The emerging technique of molecular imprinting and its future impact on biotechnology. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Turner, A.P.F. Too large to fit? Recent developments in macromolecular imprinting. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifuzzaman, M.D.; Zhao, Y. Water-soluble molecularly imprinted nanoparticle receptors with hydrogen-bond-assisted hydrophobic binding. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7518–7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, K.; Mosbach, K. Plastic antibodies: Developments and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormack, P.A.G.; Elorza, A.Z. Molecularly imprinted polymers: Synthesis and characterisation. J. Chromatogr. B 2004, 804, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spivak, D.A. Optimization, evaluation, and characterization of molecularly imprinted polymers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1779–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piletsky, S.A.; Andersson, H.S.; Nicholls, I.A. Combined hydrophobic and electrostatic interaction-based recognition in molecularly imprinted polymers. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.E.; Park, K.; Peppas, N.A. Molecular imprinting within hydrogels. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002, 54, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-L.; Wang, Y.; Hjertén, S. A novel support with artificially created recognition for the selective removal of proteins and for affinity chromatography. Chromatographia 1996, 42, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.M.; Stevenson, D.; Reddy, S.M. Investigation of protein imprinting in hydrogel-based molecularly imprinted polymers (HydroMIPs). Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 542, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, L.; El-Sharif, H.F.; Salles, M.O.; Boehm, R.D.; Narayan, R.J.; Paixão, T.R.L.C.; Reddy, S.M. MIP-based electrochemical protein profiling. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 204, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Sharif, H.F.; Hawkins, D.M.; Stevenson, D.; Reddy, S.M. Determination of protein binding affinities within hydrogel-based molecularly imprinted polymers (HydroMIPs). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 15483–15489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL-Sharif, H.F.; Yapati, H.; Kalluru, S.; Reddy, S.M. Highly selective BSA imprinted polyacrylamide hydrogels facilitated by a metal-coding MIP approach. Acta Biomater. 2015, 28, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.W.; Jeans, C.W.; Brain, K.R.; Allender, C.J.; Hlady, V.; Britt, D.W. From 3D to 2D: A review of the molecular imprinting of proteins. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006, 22, 1474–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, N.M.; Peppas, N.A. Molecularly imprinted polymers with specific recognition for macromolecules and proteins. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ma, Y.; Pan, J.; Meng, Z.; Pan, G.; Sellergren, B. Molecularly imprinted polymers with stimuli-responsive affinity: Progress and perspectives. Polymers 2015, 7, 1689–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, A.; Lieberzeit, P.A.; Dickert, F.L. Chemical sensors based on molecularly imprinted sol-gel materials. Materials 2010, 3, 2196–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liao, H.; Li, H.; Nie, L.; Yao, S. Stereoselective histidine sensor based on molecularly imprinted sol-gel films. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 336, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-García, M.E.; Laíño, R.B. Molecular imprinting in sol-gel materials: Recent developments and applications. Microchim. Acta 2005, 149, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.E. Recent developments in the molecular imprinting of proteins. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4178–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.E.; Puleo, D.A. Protein binding to peptide-imprinted porous silica scaffolds. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 137, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.-H.; Takahara, N.; Lee, S.-W.; Kunitake, T. Fabrication of glucose-sensitive TiO2 ultrathin films by molecular imprinting and selective detection of monosaccharides. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 130, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, N.; Yang, D.-H.; Selyanchyn, R.; Korposh, S.; Lee, S.-W.; Kunitake, T. Remarkable enantioselectivity of molecularly imprinted TiO2 nano-thin films. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 694, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Long, Y.; Nie, L.; Yao, S. Molecularly imprinted thin film self-assembled on piezoelectric quartz crystal surface by the sol-gel process for protein recognition. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 21, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciriminna, R.; Fidalgo, A.; Pandarus, V.; Béland, F.; Ilharco, L.M.; Pagliaro, M. The sol-gel route to advanced silica-based materials and recent applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 6592–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, Q.Y.; Zolkeflay, M.H.; Low, S.C. Configuration control on the shape memory stiffness of molecularly imprinted polymer for specific uptake of creatinine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 369, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.; Starosvetsky, J.; Cheruti, U.; Armon, R. Whole cell imprinting in sol-gel thin films for bacterial recognition in liquids: Macromolecular fingerprinting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1236–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Wan, F.; Ni, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, J. Electrochemical sensor for detection of trichlorfon based on molecularly imprinted sol-gel films modified glassy carbon electrode. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2012, 22, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.; Davis, M.E. Molecular imprinting of bulk, microporous silica. Nature 2000, 403, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schirhagl, R.; Ren, K.N.; Zare, R.N. Surface-imprinted polymers in microfluidic devices. Sci. China Chem. 2012, 55, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, J. Molecular imprinting: Perspectives and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2137–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, O.; Bindeus, R.; Haderspöck, C.; Mann, K.-J.; Wirl, B.; Dickert, F.L. Mass-sensitive detection of cells, viruses and enzymes with artificial receptors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2003, 91, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truskett, V.N.; Watts, M.P.C. Trends in imprint lithography for biological applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, R.S.; Takayama, S.; Ostuni, E.; Ingber, D.E.; Whitesides, G.M. Patterning proteins and cells using soft lithography. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 2363–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Tsai, W.-B.; Garrison, M.D.; Ferrari, S.; Ratner, B.D. Template-imprinted nanostructured surfaces for protein recognition. Nature 1999, 398, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chou, P.-C.; Rick, J.; Chou, T.-C. C-reactive protein thin-film molecularly imprinted polymers formed using a micro-contact approach. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 542, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.-X.; Rick, J.; Chou, T.-C. Selective recognition of ovalbumin using a molecularly imprinted polymer. Microchem. J. 2009, 92, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Thomas, J.L.; Wang, S.-E.; Chen, H.-C.; Chou, T.-C. The microcontact imprinting of proteins: The effect of cross-linking monomers for lysozyme, ribonuclease A and myoglobin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 22, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-Y.; Thomas, J.L.; Wu, B.-T.; Chou, T.-C. Incorporation of styrene enhances recognition of ribonuclease A by molecularly imprinted polymers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 22, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertürk, G.; Berillo, D.; Hedström, M.; Mattiasson, B. Microcontact-BSA imprinted capacitive biosensor for real-time, sensitive and selective detection of BSA. Biotechnol. Rep. 2014, 3, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, G.; Knorr, K. Stoichiometric noncovalent interaction in molecular imprinting. Bioseparation 2001, 10, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Schönhoff, M.; Zhang, X. Unconventional layer-by-layer assembly: Surface molecular imprinting and its applications. Small 2012, 8, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertürk, G.; Mattiasson, B. From imprinting to microcontact imprinting—A new tool to increase selectivity in analytical devices. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1021, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idil, N.; Hedström, M.; Denizli, A.; Mattiasson, B. Whole cell based microcontact imprinted capacitive biosensor for the detection of Escherichia coli. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, M.; Rastogi, A.; Ober, C. Polymer brushes for electrochemical biosensors. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, K.L.; Whitesides, G.M. Adsorption of proteins onto surfaces containing end-attached oligo(ethylene oxide): A model system using self-assembled monolayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 10714–10721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrwerth, S.; Eck, W.; Reinhardt, S.; Grunze, M. Factors that determine the protein resistance of oligoether self-assembled monolayers—Internal hydrophilicity, terminal hydrophilicity, and lateral packing density. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9359–9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostuni, E.; Chapman, R.G.; Holmlin, R.E.; Takayama, S.; Whitesides, G.M. A survey of structure-property relationships of surfaces that resist the adsorption of protein. Langmuir 2001, 17, 5605–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdyrko, B.; Hoy, O.; Luzinov, I. Toward protein imprinting with polymer brushes. Biointerphases 2009, 4, FA17–FA21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jain, V.; Yi, J.; Mueller, S.; Sokolov, J.; Liu, Z.; Levon, K.; Rigas, B.; Rafailovich, M.H. Potentiometric sensors based on surface molecular imprinting: Detection of cancer biomarkers and viruses. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 146, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, D.; Zhao, H. Silica particles with immobilized protein molecules and polymer brushes. Acta Biomater. 2016, 29, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.K.; Sharma, P.S.; Prasad, B.B. Electrochemical sensor for uric acid based on a molecularly imprinted polymer brush grafted to tetraethoxysilane derived sol-gel thin film graphite electrode. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2009, 29, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.B.; Tiwari, K.; Singh, M.; Sharma, P.S.; Patel, A.K.; Srivastava, S. Ultratrace analysis of dopamine using a combination of imprinted polymer-brush-coated SPME and imprinted polymer sensor techniques. Chromatographia 2009, 69, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskierko, Z.; Sharma, P.S.; Bartold, K.; Pietrzyk-Le, A.; Noworyta, K.; Kutner, W. Molecularly imprinted polymers for separating and sensing of macromolecular compounds and microorganisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Gálvez, A.; Ait-Lahcen, A.; Mercante, L.A.; Morales-Narváez, E.; Amine, A.; Merkoçi, A. Molecularly imprinted polymer-decorated magnetite nanoparticles for selective sulfonamide detection. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 3578–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, F.T.C.; Dutra, R.A.F.; Noronha, J.P.C.; Sales, M.G.F. Myoglobin-biomimetic electroactive materials made by surface molecular imprinting on silica beads and their use as ionophores in polymeric membranes for potentiometric transduction. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 4760–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Tan, T.; Svec, F. Molecular imprinting of proteins in polymers attached to the surface of nanomaterials for selective recognition of biomacromolecules. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1172–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syritski, V.; Reut, J.; Menaker, A.; Gyurcsányi, R.E.; Öpik, A. Electrosynthesized molecularly imprinted polypyrrole films for enantioselective recognition of L-aspartic acid. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 2729–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdőssy, J.; Horváth, V.; Yarman, A.; Scheller, F.W.; Gyurcsányi, R.E. Electrosynthesized molecularly imprinted polymers for protein recognition. Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 79, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, M.; Herland, A.; Karlsson, R.H.; Inganäs, O. Electrochemical devices made from conducting nanowire networks self-assembled from amyloid fibrils and alkoxysulfonate PEDOT. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 1736–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Lai, C.-W.; Chang, Y.-F.; Chan, H.-Y.; Tsai, C.-F.; Ho, J.-A.A.; Wu, L.-C. Tyramine detection using PEDOT:PSS/AuNPs/1-methyl-4-mercaptopyridine modified screen-printed carbon electrode with molecularly imprinted polymer solid phase extraction. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, W.-M.; Ho, K.-C. Amperometric morphine sensing using a molecularly imprinted polymer-modified electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 542, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, L.; Şahin, Y. Determination of paracetamol based on electropolymerized-molecularly imprinted polypyrrole modified pencil graphite electrode. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 127, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.T.C.; Ferreira, M.J.M.S.; Puga, J.R.T.; Sales, M.G.F. Screen-printed electrode produced by printed-circuit board technology. Application to cancer biomarker detection by means of plastic antibody as sensing material. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 223, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, E.; Picca, R.A.; Malitesta, C.; Piletsky, S.A.; Piletska, E.V. Development of a sensor prepared by entrapment of MIP particles in electrosynthesised polymer films for electrochemical detection of ephedrine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Cao, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhang, F.; Lu, B.; Li, F.; Xia, L.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y. Molecularly imprinted electrochemical biosensor based on chitosan/ionic liquid-graphene composites modified electrode for determination of bovine serum albumin. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 225, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.K.; Nisha, V.S.; Dhand, C.; Malhotra, B.D. Molecularly imprinted polyaniline film for ascorbic acid detection. J. Mol. Recognit. 2011, 24, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Sun, G.; Ge, L.; Ge, S.; Yu, J.; Yan, M. Photoelectrochemical lab-on-paper device based on molecularly imprinted polymer and porous Au-paper electrode. Analyst 2013, 138, 4802–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynha, T.P.; Sharma, P.S.; Sosnowska, M.; D’Souza, F.; Kutner, W. Functionalized polythiophenes: Recognition materials for chemosensors and biosensors of superior sensitivity, selectivity, and detectability. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 47, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, B.D.B.; Pernites, R.B.; Tiu, S.B.; Advincula, R.C. Detection of aspartame via microsphere-patterned and molecularly imprinted polymer arrays. Colloids Surf. A 2016, 495, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Magnetic molecularly imprinted polydopamine nanolayer on multi- walled carbon nanotubes surface for protein capture. Talanta 2015, 144, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynge, M.E.; Westen, R.; Postma, A.; Städler, B. Polydopamine—A nature-inspired polymer coating for biomedical science. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4916–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.R.; Moreira, F.T.C.; Riu, J.; Sales, M.G.F. Plastic antibody for the electrochemical detection of bacterial surface proteins. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 233, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.T.C.; Sharma, S.; Dutra, R.A.F.; Noronha, J.P.C.; Cass, A.E.G.; Sales, M.G.F. Protein-responsive polymers for point-of-care detection of cardiac biomarker. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 196, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malitesta, C.; Losito, I.; Zambonin, P.G. Molecularly imprinted electrosynthesized polymers: New materials for biomimetic sensors. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71, 1366–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Wang, C.; Peng, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Q. A novel sensitive electrochemical sensor for podophyllotoxin assay based on the molecularly imprinted poly-o-phenylenediamine film. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 2456–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossi, A.M.; Sharma, P.S.; Montana, L.; Zoccatelli, G.; Laub, O.; Levi, R. Fingerprint-imprinted polymer: Rational selection of peptide epitope templates for the determination of proteins by molecularly imprinted polymers. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 4036–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, C.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Lu, W. Active targeting of tumors through conformational epitope imprinting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5157–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, H.; Huang, C.-S.; Shea, K.J. Selective protein capture by epitope imprinting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2392–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.-N.; Duan, L.; Liu, M.; Dong, X. An epitope imprinted polymer with affinity for kininogen fragments prepared by metal coordination interaction for cancer biomarker analysis. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 7464–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwark, S.; Sun, W.; Stute, J.; Lütkemeyer, D.; Ulbricht, M.; Sellergren, B. Monoclonal antibody capture from cell culture supernatants using epitope imprinted macroporous membranes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 53162–53169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çorman, M.E.; Armutcu, C.; Uzun, L.; Say, E.; Denizli, A. Self-oriented nanoparticles for site-selective immunoglobulin G recognition via epitope imprinting approach. Colloids Surf. B 2014, 123, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dechtrirat, D.; Jetzschmann, K.J.; Stöcklein, W.F.M.; Scheller, F.W.; Gajovic-Eichelmann, N. Protein rebinding to a surface-confined imprint. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 5231–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-Y.; Zhang, X.-M.; Yan, Y.-J.; He, X.-W.; Li, W.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-K. Thermo-sensitive imprinted polymer embedded carbon dots using epitope approach. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.-J.; He, X.-W.; Li, W.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-K. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots-labeled epitope imprinted polymer with double templates via the metal chelation for specific recognition of cytochrome c. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, L.I.; Miyabayashi, A.; O’Shannessy, D.J.; Mosbach, K. Enantiomeric resolution of amino acid derivatives on molecularly imprinted polymers as monitored by potentiometric measurements. J. Chromatogr. A 1990, 516, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedborg, E.; Winquist, F.; Lundström, I.; Andersson, L.I.; Mosbach, K. Some studies of molecularly-imprinted polymer membranes in combination with field-effect devices. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 1993, 37–38, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z. An electrochemical sensor for paracetamol based on an electropolymerized molecularly imprinted o-phenylenediamine film on a multi-walled carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 5673–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, N.; Turner, A.P.F.; Tiwari, A. Electrochemical evaluation of troponin T imprinted polymer receptor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 59, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, J.D.R.M.; Santos, W.D.J.R.; Lima, P.R.; Tanaka, S.M.C.N.; Tanaka, A.A.; Kubota, L.T. A hemin-based molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) grafted onto a glassy carbon electrode as a selective sensor for 4-aminophenol amperometric. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 152, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. Electrochemical sensors of octylphenol based on molecularly imprinted poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene-gold nanoparticles). RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 57671–57677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardieu, E.; Cheap, H.; Vedrine, C.; Lazerges, M.; Lattach, Y.; Garnier, F.; Remita, S.; Pernelle, C. Molecularly imprinted conducting polymer based electrochemical sensor for detection of atrazine. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 649, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, A.; Blais, S.; Goparaju, C.M.V.; Neubert, T.; Pass, H.; Levon, K. Development of a biosensor for detection of pleural mesothelioma cancer biomarker using surface imprinting. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sokolov, J.; Rigas, B.; Levon, K.; Rafailovich, M. A potentiometric protein sensor built with surface molecular imprinting method. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 24, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Lue, R.-H. Electrochemical sensor for bisphenol A based on molecular imprinting technique and electropolymerization membrane. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2009, 37, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Udomsap, D.; Branger, C.; Culioli, G.; Dollet, P.; Brisset, H. A versatile electrochemical sensing receptor based on a molecularly imprinted polymer. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7488–7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Duan, H.; Luo, C. Electrochemical sensor based on magnetic graphene oxide@gold nanoparticles-molecular imprinted polymers for determination of dibutyl phthalate. Talanta 2015, 131, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Hu, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Yu, H.; Lei, F. Electrochemical sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymer reduced graphene oxide and gold nanoparticles modified electrode for detection of carbofuran. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 220, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, E.; Aldissi, M.; Bogomolova, A. Design of molecularly imprinted conducting polymer protein-sensing films via substrate-dopant binding. Analyst 2015, 140, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Zhu, P.; Pi, F.; Ji, J.; Sun, X. A disposable molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor based on screen-printed electrode modified with ordered mesoporous carbon and gold nanoparticles for determination of ractopamine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 775, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gohary, N.A.; Madbouly, A.; El Nashar, R.M.; Mizaikoff, B. Synthesis and application of a molecularly imprinted polymer for the voltammetric determination of famciclovir. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 65, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Cao, Q. A novel sensitive electrochemical sensor based on in-situ polymerized molecularly imprinted membranes at graphene modified electrode for artemisinin determination. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 64, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, P.; Ye, B.C.; Yao, J.; Chen, W. Supportless electrochemical sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymer modified nanoporous microrod for determination of dopamine at trace level. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 78, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Tang, H.; Cao, C.; Zhao, D.; Ding, Y. Molecularly imprinted polymer decorated nanoporous gold for highly selective and sensitive electrochemical sensors. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswini, K.K.; Vinu Mohan, A.M.; Biju, V.M. Molecularly imprinted poly(4-amino-5-hydroxy-2,7-naphthalenedisulfonic acid) modified glassy carbon electrode as an electrochemical theophylline sensor. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 65, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-H.; Wang, H.-H.; Li, W.-T.; Fang, X.-X.; Guo, X.-C.; Zhou, W.-H.; Cao, X.; Kou, D.-X.; Zhou, Z.-J.; Wu, S.-X. A novel electrochemical sensor for epinephrine based on three dimensional molecularly imprinted polymer arrays. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 222, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. Electrochemical determination of eugenol using a three-dimensional molecularly imprinted poly (p-aminothiophenol-co-p-aminobenzoic acids) film modified electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 210, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Sun, X. Electrochemical sensor based on molecularly imprinted film at Au nanoparticles-carbon nanotubes modified electrode for determination of cholesterol. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 66, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakas, I.; Salmi, Z.; Jouini, M.; Geneste, F.; Mazerie, I.; Floner, D.; Carbonnier, B.; Yagci, Y.; Chehimi, M.M. Picomolar detection of melamine using molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensors prepared by UV-graft photopolymerization. Electroanalysis 2015, 27, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Florea, A.; Farre, C.; Bonhomme, A.; Bessueille, F.; Vocanson, F.; Tran-Thi, N.-T.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensor for the sensitive detection of glyphosate herbicide. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2015, 95, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, H.; Zeng, Y.; Yin, Z.; Li, L. Electrochemical molecular imprinted sensors based on electrospun nanofiber and determination of ascorbic acid. Anal. Sci. 2015, 31, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, M.; Yang, S.; Jiao, F.; Yang, L.-Z.; Zhang, F.; He, P.-G. Label-free electrochemical multi-sites recognition of G-rich DNA using multi-walled carbon nanotubes-supported molecularly imprinted polymer with guanine sites of DNA. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 199, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieplak, M.; Szwabinska, K.; Sosnowska, M.; Chandra, B.K.C.; Borowicz, P.; Noworyta, K.; D’Souza, F.; Kutner, W. Selective electrochemical sensing of human serum albumin by semi-covalent molecular imprinting. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muti, M.; Soysal, M.; Nacak, F.M.; Gençdağ, K.; Karagözler, A.E. A novel DNA probe based on molecularly imprinted polymer modified electrode for the electrochemical monitoring of DNA. Electroanalysis 2015, 27, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.V.M.; Rodríguez, B.A.G.; Sales, G.F.; Sotomayor, M.D.P.T.; Dutra, R.F. An ultrasensitive human cardiac troponin T graphene screen-printed electrode based on electropolymerized-molecularly imprinted conducting polymer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 77, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, M.A.; Brett, A.M.O.B. Electrochemistry: Principles, Methods, and Applications; Oxford University Press, Incorporated: Oxford, UK, 1993; p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, B.R.; Euler, A.C.; Jenkins, A.L.; Uy, O.M.; Murray, G.M. Progress in the development of molecularly imprinted polymer sensors. Johns Hopkins APL Tech. Dig. 1999, 20, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Arvand, M.; Samie, H.A. A biomimetic potentiometric sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymer for the determination of memantine in tablets. Drug Test. Anal. 2013, 5, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, G.M.; Jenkins, A.L.; Bzhelyansky, A.; Uy, O.M. Molecularly imprinted polymers for the selective sequestering and sensing of ions. Johns Hopkins APL Tech. Dig. 1997, 18, 464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Dalo, M.A.; Nassory, N.S.; Abdulla, N.I.; Al-Mheidat, I.R. Azithromycin-molecularly imprinted polymer based on PVC membrane for Azithromycin determination in drugs using coated graphite electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2015, 751, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, H.; Shirzadmehr, A.; Rezaei, M. Designing and fabrication of new molecularly imprinted polymer-based potentiometric nano-graphene/ionic liquid/carbon paste electrode for the determination of losartan. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 212, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkütük, E.B.; Uğurağ, D.; Ersöz, A.; Say, R. Determination of clenbuterol by multiwalled carbon nanotube potentiometric sensors. Anal. Lett. 2016, 49, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupis-Rozmysłowicz, J.; Wagner, M.; Bobacka, J.; Lewenstam, A.; Migdalski, J. Biomimetic membranes based on molecularly imprinted conducting polymers as a sensing element for determination of taurine. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 188, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basozabal, I.; Guerreiro, A.; Gomez-Caballero, A.; Goicolea, M.A.; Barrio, R.J. Direct potentiometric quantification of histamine using solid-phase imprinted nanoparticles as recognition elements. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 58, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truta, L.A.A.N.A.; Ferreira, N.S.; Sales, M.G.F. Graphene-based biomimetic materials targeting urine metabolite as potential cancer biomarker: Application over different conductive materials for potentiometric transduction. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 150, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.S.; Wojnarowicz, A.; Sosnowska, M.; Benincori, T.; Noworyta, K.; D’Souza, F.; Kutner, W. Potentiometric chemosensor for neopterin, a cancer biomarker, using an electrochemically synthesized molecularly imprinted polymer as the recognition unit. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 77, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anirudhan, T.S.; Alexander, S.; Lilly, A. Surface modified multiwalled carbon nanotube based molecularly imprinted polymer for the sensing of dopamine in real samples using potentiometric method. Polymer 2014, 55, 4820–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayanasukha, Y.; Pratontep, S.; Porntheeraphat, S.; Bunjongpru, W.; Nukeaw, J. Non-enzymatic urea sensor using molecularly imprinted polymers surface modified based-on ion-sensitive field effect transistor (ISFET). Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 306, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, K.; Sevilla, F.B., III; Santos, J.H. Biomimetic potentiometric sensor for chlorogenic acid based on electrosynthesized polypyrrole. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 222, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, T.S.C.R.; Santos, C.; Costa-Rodrigues, J.; Fernandes, M.H.; Noronha, J.P.; Sales, M.G.F. Novel Prostate Specific Antigen plastic antibody designed with charged binding sites for an improved protein binding and its application in a biosensor of potentiometric transduction. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 132, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Buscaglia, J.; Chang, C.-C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Levon, K.; Rafailovich, M. Quantitative real-time detection of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) from pancreatic cyst fluid using 3-D surface molecular imprinting. Analyst 2016, 141, 4424–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moret, J.; Moreira, F.T.C.; Almeida, S.A.A.; Sales, M.G.F. New molecularly-imprinted polymer for carnitine and its application as ionophore in potentiometric selective membranes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 43, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergveld, P. Development of an ion-sensitive solid-state device for neurophysiological measurements. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1970, 17, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöning, M.J.; Poghossian, A. Recent advances in biologically sensitive field-effect transistors (BioFETs). Analyst 2002, 127, 1137–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabrowski, M.; Sharma, P.S.; Iskierko, Z.; Noworyta, K.; Cieplak, M.; Lisowski, W.; Oborska, S.; Kuhn, A.; Kutner, W. Early diagnosis of fungal infections using piezomicrogravimetric and electric chemosensors based on polymers molecularly imprinted with d-arabitol. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskierko, Z.; Sharma, P.S.; Prochowicz, D.; Fronc, K.; D’Souza, F.; Toczydłowska, D.; Stefaniak, F.; Noworyta, K. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Film with Improved Surface Area Developed by Using Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) for Sensitive Lipocalin (NGAL) Determination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 19860–19865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskierko, Z.; Checinska, A.; Sharma, P.S.; Golebiewska, K.; Noworyta, K.; Borowicz, P.; Fronc, K.; Bandi, V.; D’Souza, F.; Kutner, W. Molecularly imprinted polymer based extended-gate field-effect transistor chemosensors for phenylalanine enantioselective sensing. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M.; Skládal, P. Electrochemical Biosensors—Principles and applications. J. Appl. Biomed. 2008, 6, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, C.; Bjarnason, B.; Johansson, G. Capacitive biosensors. Electroanalysis 2001, 13, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasyuk, T.L.; Mirsky, V.M.; Piletsky, S.A.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Electropolymerized molecularly imprinted polymers as receptor layers in a capacitive chemical sensors. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71, 4609–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowicz, A.; Sharma, P.S.; Sosnowska, M.; Lisowski, W.; Huynh, T.-P.; Pszona, M.; Borowicz, P.; D’Souza, F.; Kutner, W. An electropolymerized molecularly imprinted polymer for selective carnosine sensing with impedimetric capacity. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleviciute, I.; Ratautaite, V.; Ramanaviciene, A.; Balevicius, Z.; Broeders, J.; Croux, D.; McDonald, M.; Vahidpour, F.; Thoelen, R.; De Ceuninck, W.; et al. Evaluation of theophylline imprinted polypyrrole film. Synth. Met. 2015, 209, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.A.V.; Hedström, M.; Mattiasson, B. Bioimprinting as a tool for the detection of aflatoxin B1 using a capacitive biosensor. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 11, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.; Tamboli, V.; Harniman, R.L.; Estrela, P.; Allender, C.J.; Bowen, J.L. Aptamer-MIP hybrid receptor for highly sensitive electrochemical detection of prostate specific antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 75, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, A.P.M.; Ferreira, N.S.; Truta, L.A.A.N.A.; Sales, M.G.F. Conductive paper with antibody-like film for electrical readings of biomolecules. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, J.M.; Wong, D.K.Y.; Halsall, H.B.; Heineman, W.R. Recent developments in electrochemical immunoassays and immunosensors. In Electrochemical Sensors, Biosensors and Their Biomedical Applications, 1st ed.; Zhang, X., Ju, H., Wang, J., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: FL/AZ, USA; Nanjing, China, 2008; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Suri, C.R. Immunosensors for pesticides monitoring. In Advances in Biosensors: Perspectives in Biosensors, 1st ed.; Malhotra, A.P.F., Turner, B.D., Eds.; Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 5, pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.A. Label-Free Biosensors Techniques and Applications, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–279. [Google Scholar]

- Syahir, A.; Usui, K.; Tomizaki, K.-Y.; Kajikawa, K.; Mihara, H. Label and Label-Free Detection Techniques for Protein Microarrays. Microarrays 2015, 4, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestergaard, M.; Kerman, K.; Tamiya, E. An overview of label-free electrochemical protein sensors. Sensors 2007, 7, 3442–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.K.; Armani, A.M. Label-free biological and chemical sensors. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 1544–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Y.; Hong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Ning, B.; Gao, Z. Ultrasensitive sensing of diethylstilbestrol based on AuNPs/MWCNTs-CS composites coupling with sol-gel molecularly imprinted polymer as a recognition element of an electrochemical sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 238, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yao, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, S.; Su, J.; Hu, G. Molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor based on Au nanoparticles in carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for sensitive determination of olaquindox in food and feedstuffs. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Duan, H.; Wang, Y.; Bu, Y.; Luo, C. Based on magnetic graphene oxide highly sensitive and selective imprinted sensor for determination of sunset yellow. Talanta 2016, 147, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analyte Category | Template/Analyte | Monomer | Electrode | Detection Technique | LOD (M) | Linear Range (M) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | Ractopamine | Aminothiophenol | Screen printed electrode | DPV | 4.23 × 10−11 | 5.0 × 10−11–1.0 × 10−9 | [137], 2016 |

| Famciclovir | Methacrylic acid and vinyl pyridine | Carbon paste electrode | CV | 7.5 × 10−7 | 2.5 × 10−6–1.0 × 10−3 | [138], 2015 | |

| Artemisinin | Acrylamide | Glassy carbon electrode | CV | 2.0 × 10−9 | 1.0 × 10−8–4.0 × 10−5 | [139], 2015 | |

| Dopamine | Aminophenol | Metallic microrod | CV | 7.63 ×10−14 | 2.0 × 10−13–2.0 × 10−8 | [140], 2016 | |

| Metronidazole | 1,2-dimethylimidazole, dimetridazole, o-phenylenediamine | Nanoporous gold leaf | CV | 1.8 × 10−11 | 5.0 × 10−11–1.0 × 10−9 and 1.0 × 10−9–1.4 × 10−6 | [141], 2015 | |

| Theophylline | 4-amino-5-hydroxy-2,7- naphthalenedisulfonic acid | Glassy carbon electrode | CA | 0.32 × 10−6 | 0.4–17 × 10−6 | [142], 2016 | |

| Epinephrine | Pyrrole | Indium tin oxide | DPV | - | 1–10 × 10−6 and 10–800 × 10−6 | [143], 2016 | |

| Carbofuran | Methyl acrylic acid | Glassy carbon electrode | DPV | 2.0 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−8–2.0 × 10−5 | [135], 2015 | |

| Eugenol | Aminobenzenethiol-co-p-aminobenzoic acid | Glass carbon electrode | LSV | 1.0 × 10−7 | 5.0 × 10−7–2.0 × 10−5 | [144], 2016 | |

| Organic molecules | Cholesterol | Aminothiophenol | Glassy carbon electrode | DPV | 3.3 × 10−14 | 1.0 × 10−13–1.0 × 10−9 | [145], 2015 |

| Melamine | Methacrylic acid | Diazonium-modified gold electrodes | SWV | 1.75 × 10−12 | 1.0 × 10−11–1.0 × 10−4 | [146], 2015 | |

| Glyphosate | p-aminothiophenol | Gold electrode | LSV | 5 × 10−15 | 5.9 × 10−15–5.9 × 10−9 | [147], 2015 | |

| Ascorbic acid | Polyvinylpyrrolidone | Glass carbon electrode | DPV | 3.0 × 10−6 | 10–1000 × 10−6 | [148], 2015 | |

| Dibutyl phthalate | Methacrylic | Gold electrode | DPV | 8.0 × 10−10 | 2.5 × 10−9–5.0 × 10−6 | [134], 2015 | |

| Biomacromolecules | Protein A | Aminophenol | SWCNT-Screen printed electrode | SWV | 0.6 × 10−9 | 23.8 × 10−9–4.76 × 10−6 | [110], 2016 |

| Guanine-rich DNA (G-rich DNA) | Methacrylic acid and guanine | MWCNT electrode | DPV | 7.52 × 10−9 | 0.05–1× 10−6 and 5–30 × 10−6 | [149], 2016 | |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | Vinylferrocene | Carbon paste electrode | SWV | 0.09 × 10−6 | 0.08 × 10−6–3.97 × 10−6 | [133], 2014 | |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | Pyrrole | Silver-Screen printed electrode | SWV and CV | 2.8 × 10−16 | 2.8 × 10−16–6.9 × 10−15 | [101], 2016 | |

| Human serum albumin | bis(2,2′-bithien-5-yl)methan | Gold electrode | DPV | 0.25 × 10−12 | 12 × 10−12–300 × 10−12 | [150], 2015 | |

| DNA | Pyridine | Carbon paste electrodes | SWV | 1.38 × 10−6 | 0–7.9 × 10−6 | [151], 2015 | |

| Troponin T | Pyrrole | Screen printed electrode | SWV | 1.64 × 10−13 | 2.74 × 10−13–2.74 × 10−12 | [152], 2016 |

| Analyte Category | Template/Analyte | Monomer | Electrode | Detection Technique | LOD (M) | Linear Range (M) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | Azithromycin | Acrylic acid and 2-vinyl pyridine | Graphite electrode | Potentiometry | 1.0 × 10−7 | 1.0 × 10−1–1.0 × 10−6 | [157], 2015 |

| Losartan | Methacrylic acid | Graphene/carbon paste electrode | Potentiometry | 1.82 × 10−9 | 3.0 × 10−9–1.0 × 10−2 | [158], 2015 | |

| Clenbuterol | Chitosan | Carbon paste electrode | Potentiometry | 0.91 × 10−11 | 1.0 × 10−7–1.0 × 10−12 | [159], 2016 | |

| Taurine | 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene | Glassy carbon disc electrodes | Potentiometry | - | 1.0 × 10−2–1.0 × 10−4 | [160], 2016 | |

| Histamine | Methacrylic acid | Solid phase extraction | Potentiometry | 1.12 × 10−6 | 1.0 ×1 0−6–1.0 × 10−2 | [161], 2014 | |

| Carnitine | Vinylbenzyl trimethylammonium chloride and 4-styrenesulfonic acid | Graphite and ITO/FTO | Potentiometry | 3.6 × 10−5 | 1.0 × 10−6–1.7 × 10−3 | [162], 2014 | |

| Neopterin | Bis-bithiophene, bithiophene derivatized with boronic acid | Pt disk-working electrode | Potentiometry | 22 × 10−6 | 0.15 × 10−3–2.5 × 10−3 | [163], 2016 | |

| Dopamine | Acrylamide grafted MWCNTs | Cu electrode surface | Potentiometry | 1.0 × 10−9 | 1.0 × 10−9–1.0 × 10−5 | [164], 2014 | |

| Urea | Poly(methyl methacrylate) | ISFET | Potentiometry | 1.0 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−4–1.0 × 10−1 | [165], 2016 | |

| Memantine hydrochloride | Methacrylic acid | — | Potentiometry | 6.0 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−5–1.0 × 10−1 | [155], 2013 | |

| Chlorogenic acid | Pyrrole | Graphite electrode | Potentiometry | 1.0 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−2–1 × 10−6 | [166], 2016 | |

| Biomacromolecules | Prostate specific antigen | Vinylbenzyl(trimethylammonium chloride), vinyl benzoate | Conductive carbon over a syringe | Potentiometry | 5.8 × 10−11 | 5.83 × 10−11–2.62 × 10−9 | [167], 2016 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | 11-Mercapto-1-undecanol | Gold electrode | Potentiometry | 2.8 × 10−12 | 2.8–8.3 × 10−11 | [168], 2016 |

| Analyte Category | Template/Analyte | Monomer | Electrode | Detection Technique | LOD (M) | Linear Range (M) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Carnosine | Carboxy and 18-crown-6 ether and bis(2,20-bithien-5 yl)methane | Gold electrode | EIS | 20 × 10−6 | 0.1 × 10−3–0.75 × 10−3 | [178], 2016 |

| Theophylline | Pyrrole | Silicon substrates | EIS | - | 0.1 × 10−9–1.0 × 10−6 | [179], 2015 | |

| Aflatoxin B1 | Ovalbumin and glutaraldheide | Gold electrode | EIS | 6.3 × 10−12 | 3.2 × 10−6–3.2 × 10−9 | [180], 2016 | |

| Biomacromolecule | Prostate specific antigen | Dopamine | Gold electrode | EIS | 2.94 × 10−14 | 2.94 × 10−9–2.94 × 10−12 | [181], 2016 |

| Protein A | Aminophenol | SWCNT-screen printed electrode | EIS | 16.8 × 10−9 | 23.8 × 10−9–2.38 × 10−6 | [110], 2016 | |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | Pyrrole | Silver- screen printed electrode | EIS | 2.8 × 10−16 | 2.8 × 10−16–6.9 × 10−15 | [101], 2016 | |

| Carnitine | 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) | Carbon-cellulose paper | EIS | 2.15 × 10−10 | 1.0 × 10−8–1.0 × 10−3 | [182], 2016 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frasco, M.F.; Truta, L.A.A.N.A.; Sales, M.G.F.; Moreira, F.T.C. Imprinting Technology in Electrochemical Biomimetic Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17030523

Frasco MF, Truta LAANA, Sales MGF, Moreira FTC. Imprinting Technology in Electrochemical Biomimetic Sensors. Sensors. 2017; 17(3):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17030523

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrasco, Manuela F., Liliana A. A. N. A. Truta, M. Goreti F. Sales, and Felismina T. C. Moreira. 2017. "Imprinting Technology in Electrochemical Biomimetic Sensors" Sensors 17, no. 3: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17030523

APA StyleFrasco, M. F., Truta, L. A. A. N. A., Sales, M. G. F., & Moreira, F. T. C. (2017). Imprinting Technology in Electrochemical Biomimetic Sensors. Sensors, 17(3), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17030523