Plant Core Environmental Stress Response Genes Are Systemically Coordinated during Abiotic Stresses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

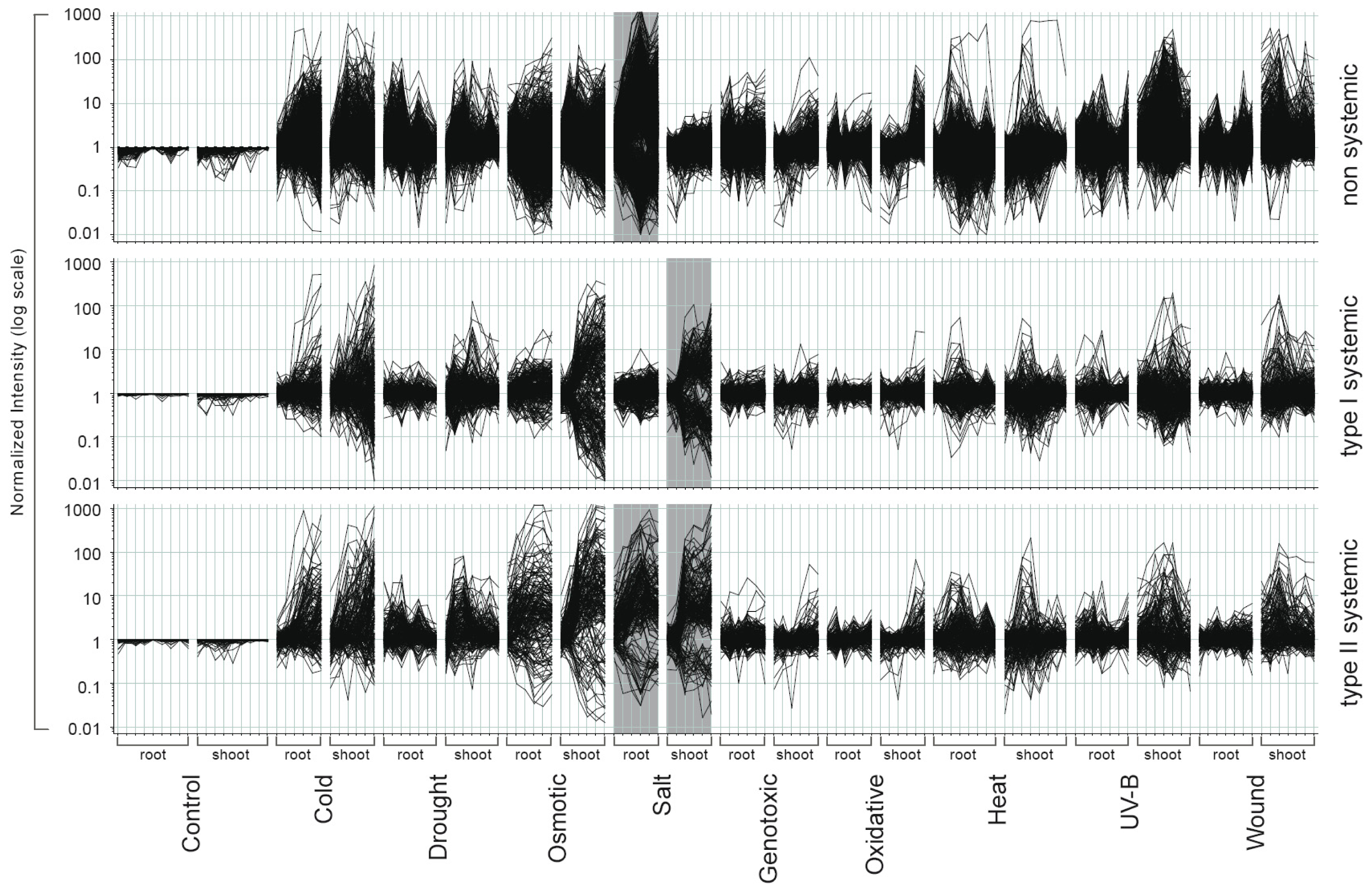

2.1. Gene Expression Responses Follow a Highly Diverse Pattern during Abiotic Stresses

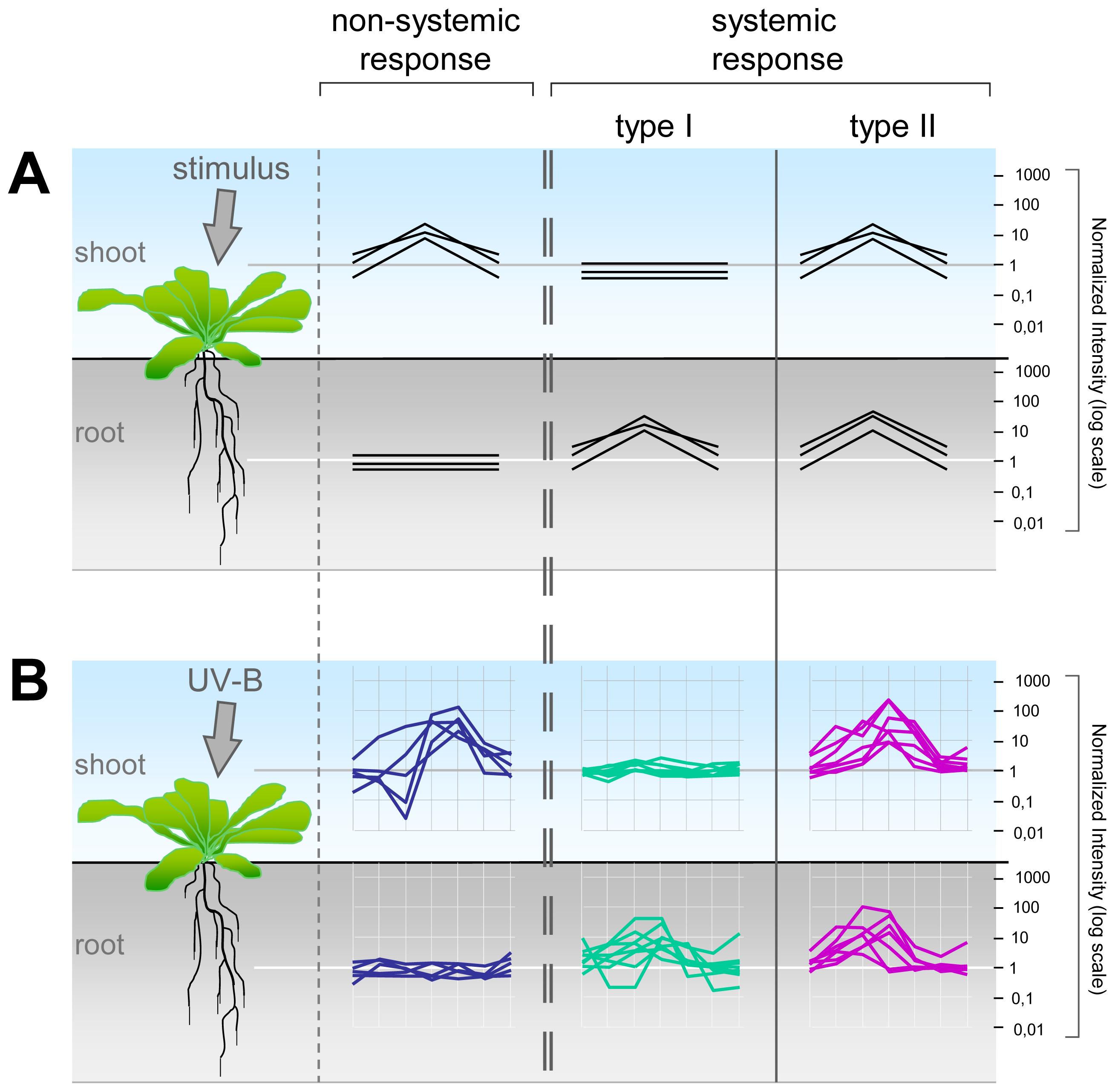

2.2. Systemic and Non-Systemic Gene Expression Responses

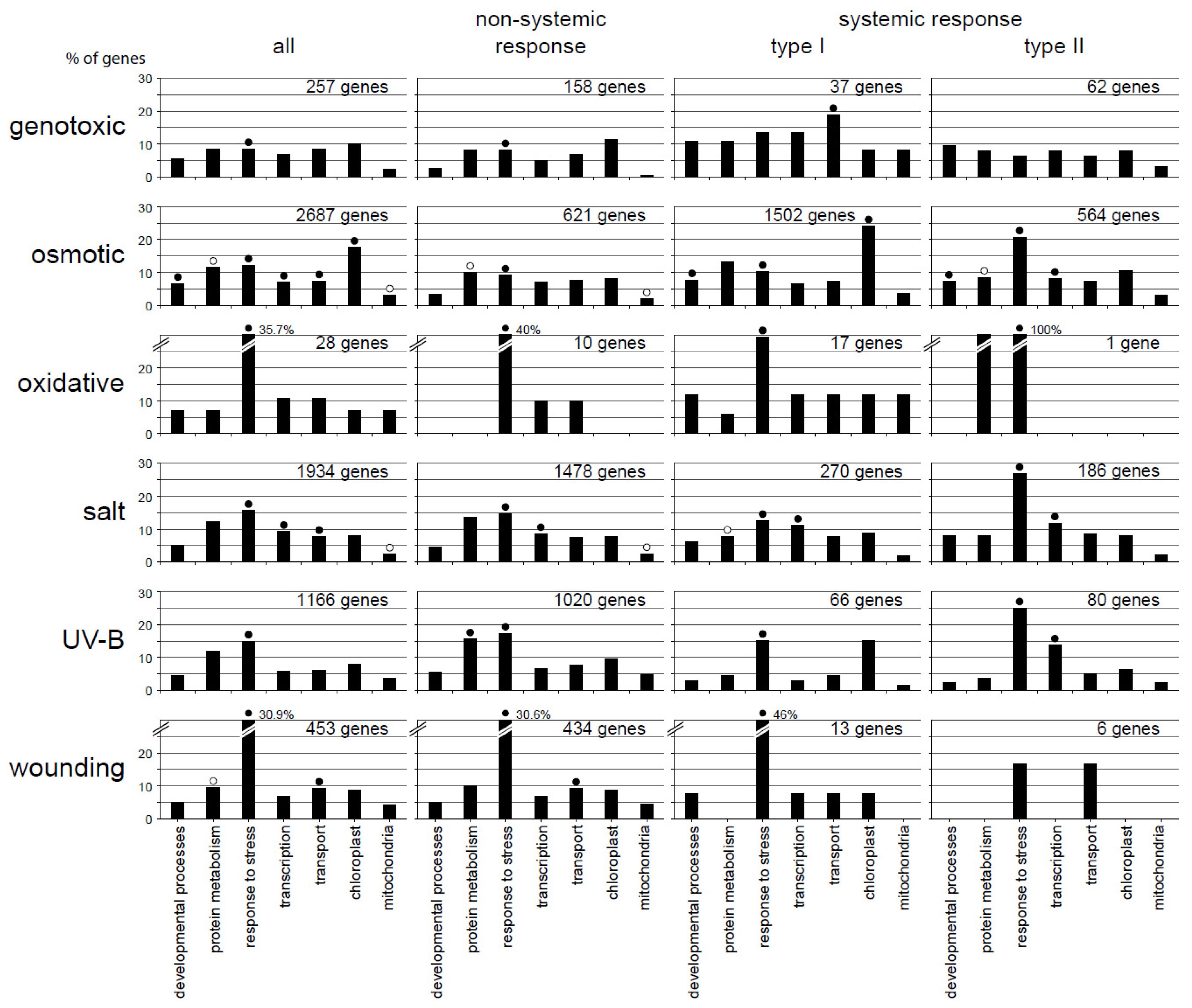

2.3. Functional Categorization Uncovers Specificity in the Different Response Patterns

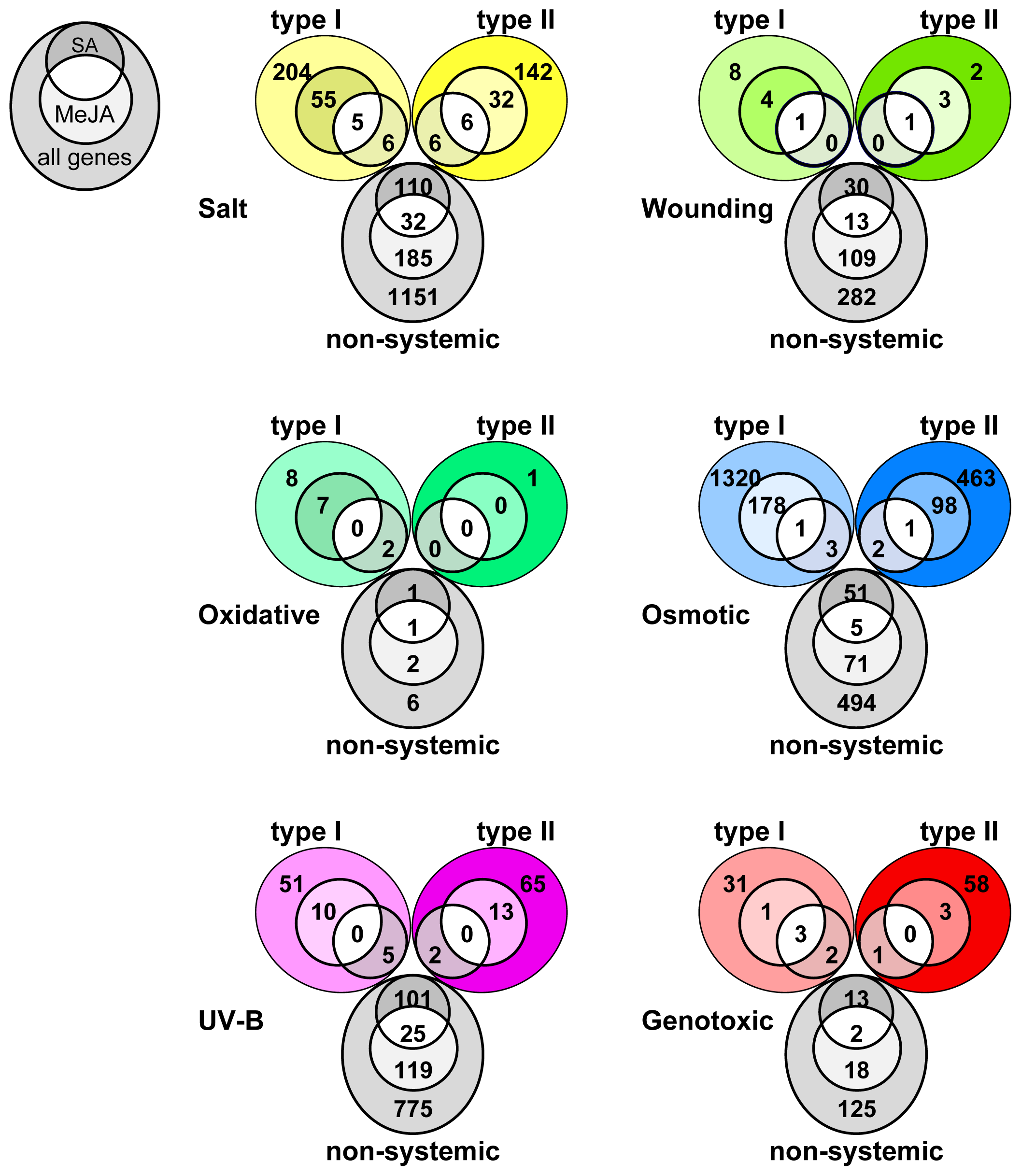

2.4. Overlap in Non-Systemic, Type I and Type II Systemic Stress Responses

2.5. The Systemic Stress Response Utilizes Jasmonic Acid

2.6. WRKY Genes Are Mainly Involved in the Non-Systemic Stress Response

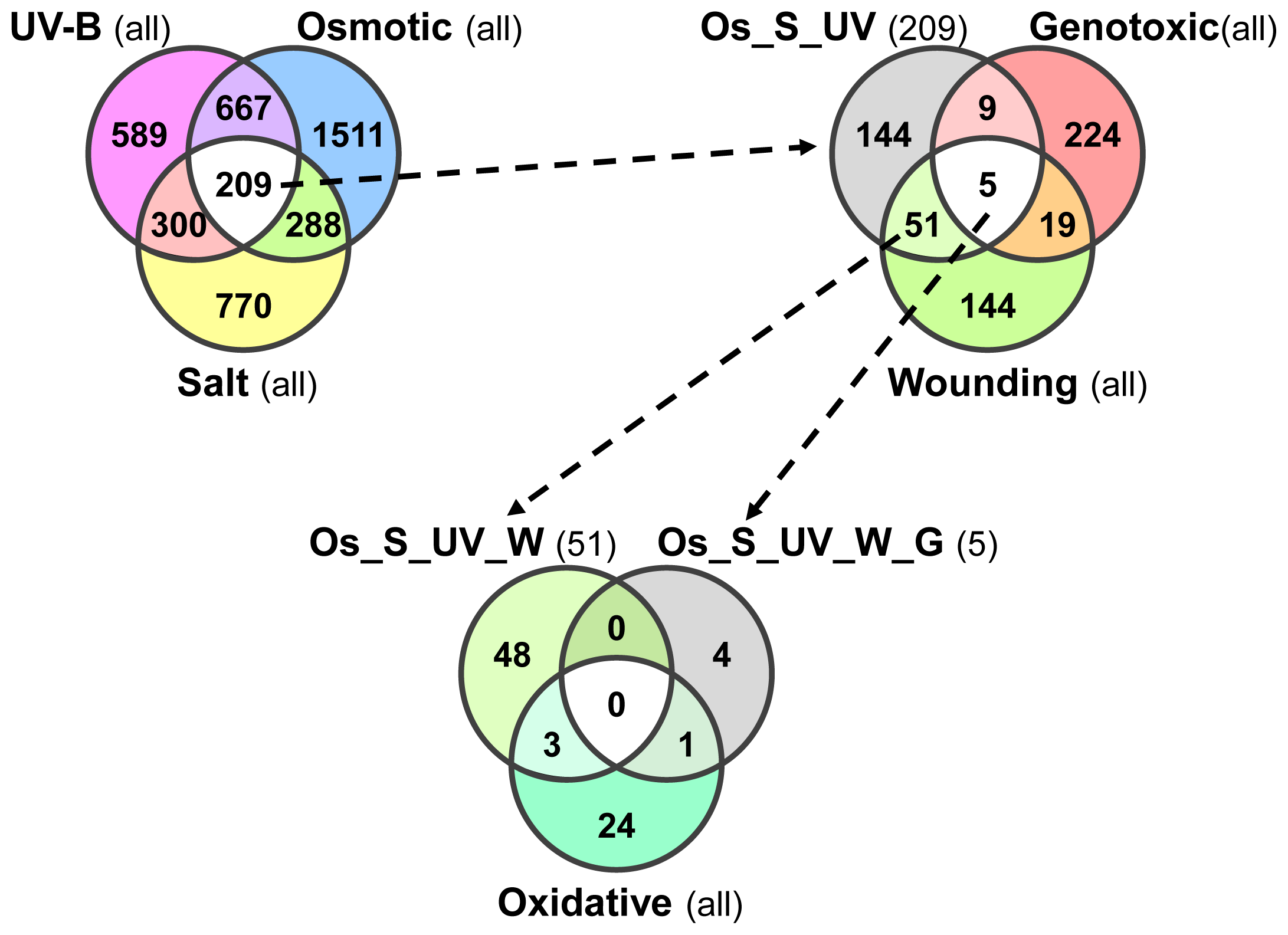

2.7. Plant Core Environmental Stress Response (PCESR) Genes

2.8. PCESR Genes Are Systemically Coordinated during Abiotic Stresses

2.9. Stress-Induced Systemic Signaling Uses Multiple Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Microarray Data Processing

4.2. Gene List Analysis

4.3. Network Graph Analysis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- De Wit, P.J. How plants recognize pathogens and defend themselves. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2007, 64, 2726–2732. [Google Scholar]

- Guimil, S.; Chang, H.S.; Zhu, T.; Sesma, A.; Osbourn, A.; Roux, C.; Ioannidis, V.; Oakeley, E.J.; Docquier, M.; Descombes, P.; et al. Comparative transcriptomics of rice reveals an ancient pattern of response to microbial colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8066–8070. [Google Scholar]

- Kilian, J.; Peschke, F.; Berendzen, K.W.; Harter, K.; Wanke, D. Prerequisites, performance and profits of transcriptional profiling the abiotic stress response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kilian, J.; Whitehead, D.; Horak, J.; Wanke, D.; Weinl, S.; Batistic, O.; D’Angelo, C.; Bornberg-Bauer, E.; Kudla, J.; Harter, K. The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: Protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2007, 50, 347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A.; Aalen, R.B.; Audenaert, D.; Beeckman, T.; Broadley, M.R.; Butenko, M.A.; Cano-Delgado, A.I.; de Vries, S.; Dresselhaus, T.; Felix, G.; et al. Tackling drought stress: Receptor-Like kinases present new approaches. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2262–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Puig, J.; Pauluzzi, G.; Guiderdoni, E.; Gantet, P. Regulation of shoot and root development through mutual signaling. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 974–983. [Google Scholar]

- Buhtz, A.; Pieritz, J.; Springer, F.; Kehr, J. Phloem small RNAs, nutrient stress responses, and systemic mobility. BMC Plant Biol 2010, 10, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, B.D.; Buhtz, A.; Kehr, J.; Scheible, W.R. MicroRNA399 is a long-distance signal for the regulation of plant phosphate homeostasis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2008, 53, 731–738. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.C.; Yu, T.S. The sequences of Arabidopsis GA-INSENSITIVE RNA constitute the motifs that are necessary and sufficient for RNA long-distance trafficking. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2009, 59, 921–929. [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier, L.; Vincent, C.; Jang, S.; Fornara, F.; Fan, Q.; Searle, I.; Giakountis, A.; Farrona, S.; Gissot, L.; Turnbull, C.; et al. FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 2007, 316, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Schlereth, A.; Moller, B.; Liu, W.; Kientz, M.; Flipse, J.; Rademacher, E.H.; Schmid, M.; Jurgens, G.; Weijers, D. MONOPTEROS controls embryonic root initiation by regulating a mobile transcription factor. Nature 2010, 464, 913–916. [Google Scholar]

- Bahyrycz, A.; Konopinska, D. Plant signalling peptides: Some recent developments. J. Peptide Sci. Off. Publ. Eur. Peptide Soc 2007, 13, 787–797. [Google Scholar]

- Vlot, A.C.; Klessig, D.F.; Park, S.W. Systemic acquired resistance: The elusive signal(s). Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 2008, 11, 436–442. [Google Scholar]

- Beckers, G.J.; Spoel, S.H. Fine-Tuning plant defence signalling: Salicylate versus Jasmonate. Plant Biol 2006, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gfeller, A.; Baerenfaller, K.; Loscos, J.; Chetelat, A.; Baginsky, S.; Farmer, E.E. Jasmonate controls polypeptide patterning in undamaged tissue in wounded Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol 2011, 156, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, I.F.; Farmer, E.E. Jasmonates. In The Arabidopsis book 8; American Society of Plant Biologists, American Society of Plant Biologists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2010; Volume 8, p. e0129. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.W.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Wang, L.; Glazebrook, J.; Greenberg, J.T. Priming in systemic plant immunity. Science 2009, 324, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mehterov, N.; Balazadeh, S.; Hille, J.; Toneva, V.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T. Oxidative stress provokes distinct transcriptional responses in the stress-tolerant atr7 and stress-sensitive loh2 Arabidopsis thaliana mutants as revealed by multi-parallel quantitative real-time PCR analysis of ROS marker and antioxidant genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB Soc. Fr. Physiol. Veg 2012, 59, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.; Schlauch, K.; Tam, R.; Cortes, D.; Torres, M.A.; Shulaev, V.; Dangl, J.L.; Mittler, R. The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD mediates rapid systemic signaling in response to diverse stimuli. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra45. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, S.; Kawarazaki, T.; Nibori, H.; Michikawa, M.; Imai, A.; Kaya, H.; Kuchitsu, K. The CBL-interacting protein kinase CIPK26 is a novel interactor of Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase AtRbohF that negatively modulates its ROS-producing activity in a heterologous expression system. J. Biochem 2013, 153, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Pitzschke, A.; Hirt, H. Mitogen-Activated protein kinases and reactive oxygen species signaling in plants. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.E.; Pennell, R.I.; Meijer, P.J.; Ishikawa, A.; Dixon, R.A.; Lamb, C. Reactive oxygen intermediates mediate a systemic signal network in the establishment of plant immunity. Cell 1998, 92, 773–784. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, E. New functions for electrical signals in plants. New Phytol 2004, 161, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, M.R.; Maischak, H.; Mithofer, A.; Boland, W.; Felle, H.H. System potentials, a novel electrical long-distance apoplastic signal in plants, induced by wounding. Plant Physiol 2009, 149, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Felle, H.H.; Zimmermann, M.R. Systemic signalling in barley through action potentials. Planta 2007, 226, 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra, A.S.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Christmann, A.; Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci 2010, 15, 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Christmann, A.; Weiler, E.W.; Steudle, E.; Grill, E. A hydraulic signal in root-to-shoot signalling of water shortage. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2007, 52, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Kim, M.S.; Cho, K.H. The core regulation module of stress-responsive regulatory networks in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 8793–8802. [Google Scholar]

- Gasch, A.P. Comparative genomics of the environmental stress response in ascomycete fungi. Yeast 2007, 24, 961–976. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.C.; Kissinger, M.T.; Burke, P.V.; Kwast, K.E. Comparison of the transcriptomic “stress response” evoked by antimycin A and oxygen deprivation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Causton, H.C.; Ren, B.; Koh, S.S.; Harbison, C.T.; Kanin, E.; Jennings, E.G.; Lee, T.I.; True, H.L.; Lander, E.S.; Young, R.A. Remodeling of yeast genome expression in response to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Toone, W.M.; Mata, J.; Lyne, R.; Burns, G.; Kivinen, K.; Brazma, A.; Jones, N.; Bahler, J. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 214–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wanke, D.; Berendzen, K.W.; Kilian, J.; Harter, K. Insights into the Arabidopsis Abiotic Stress Response from the AtGenExpress Expression Profile Dataset. In Plant Stress Biology; Hirt, H., Ed.; WILEY-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsen, E.; Kilian, J.; Harter, K.; Jansson, C.; Wanke, D.; Sundberg, E. Transcriptome analysis of high-temperature stress in developing barley caryopses: Early stress responses and effects on storage compound biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, G.; Danyluk, J.; Charron, J.B.; Sarhan, F. Expression profiling and bioinformatic analyses of a novel stress-regulated multispanning transmembrane protein family from cereals and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2003, 132, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.T.; Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Ham le, H.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.S. Differential gene expression in soybean leaf tissues at late developmental stages under drought stress revealed by genome-wide transcriptome analysis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e49522. [Google Scholar]

- Andi, S.; Taguchi, F.; Toyoda, K.; Shiraishi, T.; Ichinose, Y. Effect of methyl jasmonate on harpin-induced hypersensitive cell death, generation of hydrogen peroxide and expression of PAL mRNA in tobacco suspension cultured BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol 2001, 42, 446–449. [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R. Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends Plant Sci 2006, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, D.L.; Tripathi, P.; Rabara, R.C.; Lin, J.; Ringler, P.; Boken, A.K.; Langum, T.J.; Smidt, L.; Boomsma, D.D.; Emme, N.J.; et al. WRKY transcription factors: Key components in abscisic acid signalling. Plant Biotechnol. J 2012, 10, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wenke, K.; Wanke, D.; Kilian, J.; Berendzen, K.; Harter, K.; Piechulla, B. Volatiles of two growth-inhibiting rhizobacteria commonly engage AtWRKY18 function. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2012, 70, 445–459. [Google Scholar]

- Babitha, K.C.; Ramu, S.V.; Pruthvi, V.; Mahesh, P.; Nataraja, K.N.; Udayakumar, M. Co-Expression of AtbHLH17 and AtWRKY28 confers resistance to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis. Transgenic Res 2012, 22, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.; Hong, X.; Zhu, J.K.; Gong, Z. ABO3, a WRKY transcription factor, mediates plant responses to abscisic acid and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2010, 63, 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Davletova, S.; Schlauch, K.; Coutu, J.; Mittler, R. The zinc-finger protein Zat12 plays a central role in reactive oxygen and abiotic stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2005, 139, 847–856. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, H.; Maruyama, K.; Sakuma, Y.; Meshi, T.; Iwabuchi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger proteins function as transcription repressors under drought, cold, and high-salinity stress conditions. Plant Physiol 2004, 136, 2734–2746. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Clarenz, O.; Cokus, S.; Bernatavichute, Y.V.; Pellegrini, M.; Goodrich, J.; Jacobsen, S.E. Whole-Genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol 2007, 5, e129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yazaki, J.; Sundaresan, A.; Cokus, S.; Chan, S.W.; Chen, H.; Henderson, I.R.; Shinn, P.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E.; et al. Genome-Wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in arabidopsis. Cell 2006, 126, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Haberer, G.; Mader, M.T.; Kosarev, P.; Spannagl, M.; Yang, L.; Mayer, K.F. Large-Scale cis-element detection by analysis of correlated expression and sequence conservation between Arabidopsis and Brassica oleracea. Plant Physiol 2006, 142, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, H.; Motomura, T.; Komeda, Y.; Saito, T.; Kato, A. Overexpression of the NAC transcription factor family gene ANAC036 results in a dwarf phenotype in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Physiol 2010, 167, 571–577. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, P.J.; Park, C.M. A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor as an integrator of biotic and abiotic stress signals. Plant Signal. Behav 2010, 5, 481–483. [Google Scholar]

- Walley, J.W.; Kelley, D.R.; Nestorova, G.; Hirschberg, D.L.; Dehesh, K. Arabidopsis deadenylases AtCAF1a and AtCAF1b play overlapping and distinct roles in mediating environmental stress responses. Plant Physiol 2010, 152, 866–875. [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack, C. Jasmonates: An update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot 2007, 100, 681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Glauser, G.; Dubugnon, L.; Mousavi, S.A.; Rudaz, S.; Wolfender, J.L.; Farmer, E.E. Velocity estimates for signal propagation leading to systemic jasmonic acid accumulation in wounded Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem 2009, 284, 34506–34513. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, A.J.; Gao, X.; Jones, A.D.; Howe, G.A. A rapid wound signal activates the systemic synthesis of bioactive jasmonates in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2009, 59, 974–986. [Google Scholar]

- Mithofer, A.; Wanner, G.; Boland, W. Effects of feeding Spodoptera littoralis on lima bean leaves. II. Continuous mechanical wounding resembling insect feeding is sufficient to elicit herbivory-related volatile emission. Plant Physiol 2005, 137, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M.H.; Grima-Pettenati, J.; Grand, C.; Boudet, A.M.; Lamb, C.J. Cinnamyl-Alcohol dehydrogenase, a molecular marker specific for lignin synthesis: cDNA cloning and mRNA induction by fungal elicitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 5546–5550. [Google Scholar]

- Lois, R.; Dietrich, A.; Hahlbrock, K.; Schulz, W. A phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene from parsley: Structure, regulation and identification of elicitor and light responsive cis-acting elements. EMBO J 1989, 8, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, C.J.; Hauffe, K.D.; Ites-Morales, M.E.; Ellard, M.; Paszkowski, U.; Hahlbrock, K.; Dangl, J.L. Exonic sequences are required for elicitor and light activation of a plant defense gene, but promoter sequences are sufficient for tissue specific expression. EMBO J 1991, 10, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Delessert, C.; Wilson, I.W.; van Der Straeten, D.; Dennis, E.S.; Dolferus, R. Spatial and temporal analysis of the local response to wounding in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Mol. Biol 2004, 55, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Shimmen, T. Electrical perception of “death message” in Chara: Involvement of turgor pressure. Plant Cell Physiol 2001, 42, 366–373. [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R.; Kim, Y.; Song, L.; Coutu, J.; Coutu, A.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Lee, H.; Stevenson, B.; Zhu, J.K. Gain- and loss-of-function mutations in Zat10 enhance the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 6537–6542. [Google Scholar]

- Rossel, J.B.; Wilson, P.B.; Hussain, D.; Woo, N.S.; Gordon, M.J.; Mewett, O.P.; Howell, K.A.; Whelan, J.; Kazan, K.; Pogson, B.J. Systemic and intracellular responses to photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 4091–4110. [Google Scholar]

- Lang-Mladek, C.; Popova, O.; Kiok, K.; Berlinger, M.; Rakic, B.; Aufsatz, W.; Jonak, C.; Hauser, M.T.; Luschnig, C. Transgenerational inheritance and resetting of stress-induced loss of epigenetic gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Latrasse, D.; Germann, S.; Houba-Herin, N.; Dubois, E.; Bui-Prodhomme, D.; Hourcade, D.; Juul-Jensen, T.; Le Roux, C.; Majira, A.; Simoncello, N.; et al. Control of flowering and cell fate by LIF2, an RNA binding partner of the polycomb complex component LHP1. PLoS One 2011, 6, e16592. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, C.S.; Lee, D.; Choi, G.; Chung, W.I. Histone occupancy-dependent and -independent removal of H3K27 trimethylation at cold-responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2009, 60, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk, I.; Kovalchuk, O.; Kalck, V.; Boyko, V.; Filkowski, J.; Heinlein, M.; Hohn, B. Pathogen-Induced systemic plant signal triggers DNA rearrangements. Nature 2003, 423, 760–762. [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman, R.C.; Carey, V.J.; Bates, D.M.; Bolstad, B.; Dettling, M.; Dudoit, S.; Ellis, B.; Gautier, L.; Ge, Y.; Gentry, J.; et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R80. [Google Scholar]

- The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.r-project.org (accessed on 1 April 2012).

- GO term enrichment at The Arabidopsis Information Resource’s Gene Ontology (GO) annotation search page. Available online: http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/go/index.jsp (accessed on 10 May 2011).

- Plot 0.997. Available online: http://plot.micw.eu/ (accessed on 1 April 2012).

- O’Connor, T.R.; Dyreson, C.; Wyrick, J.J. Athena: A resource for rapid visualization and systematic analysis of Arabidopsis promoter sequences. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 4411–4413. [Google Scholar]

- AGI Conversion Tool. Availble online: http://bar.utoronto.ca/ntools/cgi-bin/ntools_agi_converter.cgi (accessed on 11 May 2012).

- Perez-Rodriguez, P.; Riano-Pachon, D.M.; Correa, L.G.; Rensing, S.A.; Kersten, B.; Mueller-Roeber, B. PlnTFDB: Updated content and new features of the plant transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, D822–D827. [Google Scholar]

- Goda, H.; Sasaki, E.; Akiyama, K.; Maruyama-Nakashita, A.; Nakabayashi, K.; Li, W.; Ogawa, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Preston, J.; Aoki, K.; et al. The AtGenExpress hormone and chemical treatment data set: Experimental design, data evaluation, model data analysis and data access. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol 2008, 55, 526–542. [Google Scholar]

- Motif Mapper script collection. Available online: http://www.zmbp.uni-tuebingen.de/plant-physiology/research-groups/harter/berendzen/programs.html (accessed on 10 May 2011).

- Berendzen, K.W.; Stuber, K.; Harter, K.; Wanke, D. Cis-Motifs upstream of the transcription and translation initiation sites are effectively revealed by their positional disequilibrium in eukaryote genomes using frequency distribution curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, M.S.; Smoot, M.; Cerami, E.; Kuchinsky, A.; Landys, N.; Workman, C.; Christmas, R.; Avila-Campilo, I.; Creech, M.; Gross, B.; et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nat. Protoc 2007, 2, 2366–2382. [Google Scholar]

| Total | Root | Shoot | Non-Systemic | Systemic Type I | Systemic Type II | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotoxic | 257 | 220 | 99 | 158 | 37 | 62 |

| Osmotic | 2,687 | 1,185 | 2,066 | 621 | 1,502 | 564 |

| Oxidative | 28 | 11 | 18 | 10 | 17 | 1 |

| Salt | 1,934 | 1,664 | 456 | 1,478 | 270 | 186 |

| UV-B | 1,166 | 146 | 1,100 | 1,020 | 66 | 80 |

| Wounding | 453 | 19 | 440 | 434 | 13 | 6 |

| Non-Systemic | Systemic Type I | Systemic Type II | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotoxic | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Osmotic | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Oxidative | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Salt | 21 | 1 | 0 |

| UV-B | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| Wounding | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Affy ID | AGI | Description | CDU | TR | H3K27me3 | Paralog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 263584_AT | At2g17040 | Anac036 | x | x | ||

| 252278_AT | At3g49530 | Anac062 | x | x | ||

| 257644_AT | At3g25780 | Allene oxide cyclase 3 | p | |||

| 264217_AT | At1g60190 | AtPUB19 E3 ubiquitin ligase | p | |||

| 246099_AT | At5g20230 | Blue-copper binding SAG14 | x | |||

| 265480_AT | At2g15970 | AtCOR413-PM1/Cyclophilin 19 | ||||

| 259789_AT | At1g29395 | AtCOR413-TM1 | p | |||

| 255479_AT | At4g02380 | AtLEA5/SAG21 | p | |||

| 246272_AT | At4g37150 | Methyl esterase 9 | x | p | ||

| 252053_AT | At3g52400 | AtSYP122 syntaxin | ||||

| 253485_AT | At4g31800 | AtWRKY18 | x | p | ||

| 257022_AT | At3g19580 | AZF2 | x | x | p | |

| 252679_AT | At3g44260 | CAF1a/CCR4-associated factor 1 | x | x | x | x |

| 249928_AT | At5g22250 | CAF1b/CCR4-associated factor 1 | x | x | ||

| 250149_AT | At5g14700 | Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase-related | ||||

| 263497_AT | At2g42540 | AtCOR15A | x | p | ||

| 254232_AT | At4g23600 | AtCORI3 | x | p | ||

| 247071_AT | At5g66640 | AtDAR3 | p | |||

| 252102_AT | At3g50970 | Dehydrin XERO2 | ||||

| 252265_AT | At3g49620 | Dark inducible 11 | x | p | ||

| 256526_AT | At1g66090 | TIR-NBS disease resistance protein | x | |||

| 249264_S_AT | At5g41740 At5g41750 | TIR-NBS disease resistance proteins | o | |||

| 262325_AT | At1g64160 | Dirigent family protein AtDIR5 | ||||

| 264436_AT | At1g10370 | ERD9 | p | |||

| 261470_AT | At1g28370 | ERF11 | x | x | p | |

| 248799_AT | At5g47230 | ERF5 | x | x | p | |

| 265276_AT | At2g28400 | Protein of unknown function | ||||

| 259445_AT | At1g02400 | Gibberellin oxidase 6 | ||||

| 266555_AT | At2g46270 | G-box binding factor 3 | x | |||

| 265725_AT | At2g32030 | GNAT family protein | x | p | ||

| 266142_AT | At2g39030 | GNAT family protein | x | x | p | |

| 251200_AT | At3g63010 | Gibberellin receptor GID1B | ||||

| 258792_AT | At3g04640 | RNA-binding glycine-rich protein | x | |||

| 250279_AT | At5g13200 | GRAM domain-containing protein | ||||

| 262930_AT | At1g65690 | LEA-related/HIN1-related | ||||

| 246214_AT | At4g36990 | Heat shock factor protein 4 | x | |||

| 248327_AT | At5g52750 | Heavy-metal-transport superfamily | p | |||

| 265724_AT | At2g32100 | Ovate family protein 16 | x | p | ||

| 250793_AT | At5g05600 | Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase | ||||

| 248164_AT | At5g54490 | EF-hand containing PBP1 | ||||

| 264580_AT | At1g05340 | Protein of unknown function | p | |||

| 256933_AT | At3g22600 | Lipid-binding protein | p | |||

| 252470_AT | At3g46930 | Protein kinase family protein | p | |||

| 258650_AT | At3g09830 | Protein kinase family protein | ||||

| 266834_S_AT | At2g30020 At3g27140 At4g08260 | Protein phosphatase 2C | o | |||

| 251259_AT | At3g62260 | Protein phosphatase 2C | ||||

| 253140_AT | At4g35480 | RING finger protein RHA3B | x | p | ||

| 252921_AT | At4g39030 | MATE-transporter SID1/EDS5 | ||||

| 256017_AT | At1g19180 | TIFY10A/JAZ1 | x | p | ||

| 254321_AT | At4g22590 | Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase | ||||

| 266452_AT | At2g43320 | Putative methyltransferase | ||||

| 250796_AT | At5g05300 | Protein of unknown function | x | |||

| 254500_AT | At4g20110 | Vacuolar sorting receptor 7 | p | |||

| 261648_AT | At1g27730 | ZAT10 | x | x | ||

| 247655_AT | At5g59820 | ZAT12 | x | x | x | |

| 245711_AT | At5g04340 | ZAT6 | x | x |

| AGI | Description | oxidative | genotoxic | osmotic | salt | UV-B | wounding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At5g66640 | AtDAR3 | • | nsy | nsy | nsy | • | nsy |

| At4g31800 | AtWRKY18 | • | • | nsy | nsy | • | nsy |

| At1g64160 | Dirigent family protein AtDIR5 | nsy | nsy | nsy | nsy | I | I |

| At5g05600 | Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase | • | • | II | II | nsy | II |

| At1g27730 | ZAT10 | I | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At4g02380 | AtLEA5/SAG21 | I | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At3g49620 | Dark inducible 11 | I | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At5g52750 | Heavy-metal-transport superfamily | • | II | I | II | II | nsy |

| At1g10370 | ERD9 | • | • | II | I | I | nsy |

| At5g14700 | Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase-related | • | • | II | II | II | nsy |

| At1g29395 | AtCOR413-TM1 | • | I | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At2g15970 | AtCOR413-PM1/Cyclophilin 19 | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At2g17040 | Anac036 | • | I | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At2g17040 | Anac036 | • | I | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g49530 | Anac062 | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g25780 | Allene oxide cyclase 3 | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g52400 | AtSYP122 syntaxin | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At5g22250 | CAF1b/CCR4-associated factor 1 | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g44260 | CAF1a/CCR4-associated factor 1 | • | • | II | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At5g47230 | ERF5 | • | • | I | nsy | • | nsy |

| At1g28370 | ERF11 | • | • | II | nsy | • | nsy |

| At4g37150 | Methyl esterase 9 | • | • | II | I | • | nsy |

| At4g23600 | AtCORI3 | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At2g42540 | AtCOR15A | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At3g19580 | AZF2 | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At3g50970 | Dehydrin XERO2 | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At2g46270 | G-box binding factor 3 | • | • | II | II | • | nsy |

| At5g13200 | GRAM domain-containing protein | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At2g28400 | Protein of unknown function | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At1g60190 | AtPUB19 E3 ubiquitin ligase | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At1g19180 | TIFY10A/JAZ1 | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At5g59820 | ZAT12 | • | • | II | II | • | nsy |

| At5g04340 | ZAT6 | • | • | II | II | nsy | nsy |

| At5g05300 | Protein of unknown function | • | • | I | II | nsy | nsy |

| At4g36990 | Heat shock factor protein 4 | • | • | I | II | nsy | nsy |

| At2g32030 | GNAT family protein | • | • | I | nsy | II | nsy |

| At2g39030 | GNAT family protein | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At3g63010 | Gibberellin receptor GID1B | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At1g65690 | LEA-related/HIN1-related | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At3g22600 | Lipid-binding protein | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At2g32100 | Ovate family protein 16 | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At4g20110 | Vacuolar sorting receptor 7 | • | • | I | I | nsy | nsy |

| At5g54490 | EF-hand containing PBP1 | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At4g39030 | MATE-transporter SID1/EDS5 | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At2g43320 | Putative methyltransferase | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g46930 | Protein kinase family protein | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g09830 | Protein kinase family protein | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At2g30020 At3g27140 At4g08260 | Protein phosphatase 2C | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At4g22590 | Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase | • | • | I | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At1g66090 | TIR-NBS disease resistance protein | • | • | I | nsy | • | nsy |

| At5g41740 At5g41750 | TIR-NBS disease resistance proteins | • | • | II | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At5g20230 | Blue-copper binding SAG14 | • | • | II | nsy | • | nsy |

| At1g02400 | Gibberellin oxidase 6 | • | • | II | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g62260 | Protein phosphatase 2C | • | • | II | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At3g04640 | RNA-binding glycine-rich protein | • | • | II | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At4g35480 | RING finger protein RHA3B | • | • | II | nsy | nsy | nsy |

| At1g05340 | Protein of unknown function | • | • | II | nsy | • | nsy |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hahn, A.; Kilian, J.; Mohrholz, A.; Ladwig, F.; Peschke, F.; Dautel, R.; Harter, K.; Berendzen, K.W.; Wanke, D. Plant Core Environmental Stress Response Genes Are Systemically Coordinated during Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7617-7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047617

Hahn A, Kilian J, Mohrholz A, Ladwig F, Peschke F, Dautel R, Harter K, Berendzen KW, Wanke D. Plant Core Environmental Stress Response Genes Are Systemically Coordinated during Abiotic Stresses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(4):7617-7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047617

Chicago/Turabian StyleHahn, Achim, Joachim Kilian, Anne Mohrholz, Friederike Ladwig, Florian Peschke, Rebecca Dautel, Klaus Harter, Kenneth W. Berendzen, and Dierk Wanke. 2013. "Plant Core Environmental Stress Response Genes Are Systemically Coordinated during Abiotic Stresses" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 4: 7617-7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047617

APA StyleHahn, A., Kilian, J., Mohrholz, A., Ladwig, F., Peschke, F., Dautel, R., Harter, K., Berendzen, K. W., & Wanke, D. (2013). Plant Core Environmental Stress Response Genes Are Systemically Coordinated during Abiotic Stresses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(4), 7617-7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047617