Interaction of Human Serum Album and C60 Aggregates in Solution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

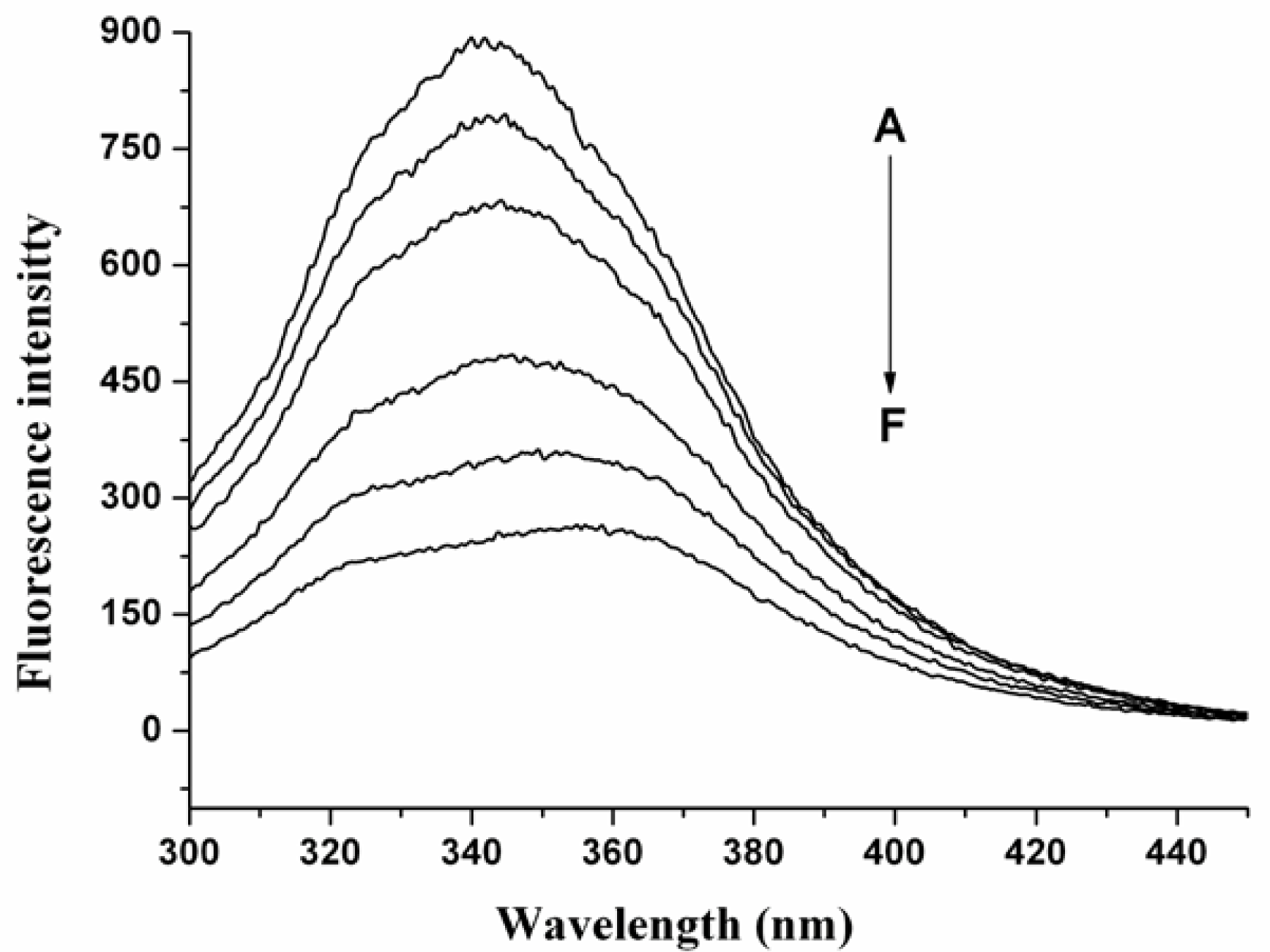

2.1 The Fluorescence Quenching of HSA by nC60

2.2. Quenching Mechanism of nC60 to HSA

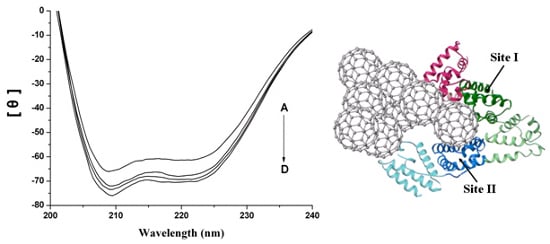

2.3. The Conformation Study of HSA

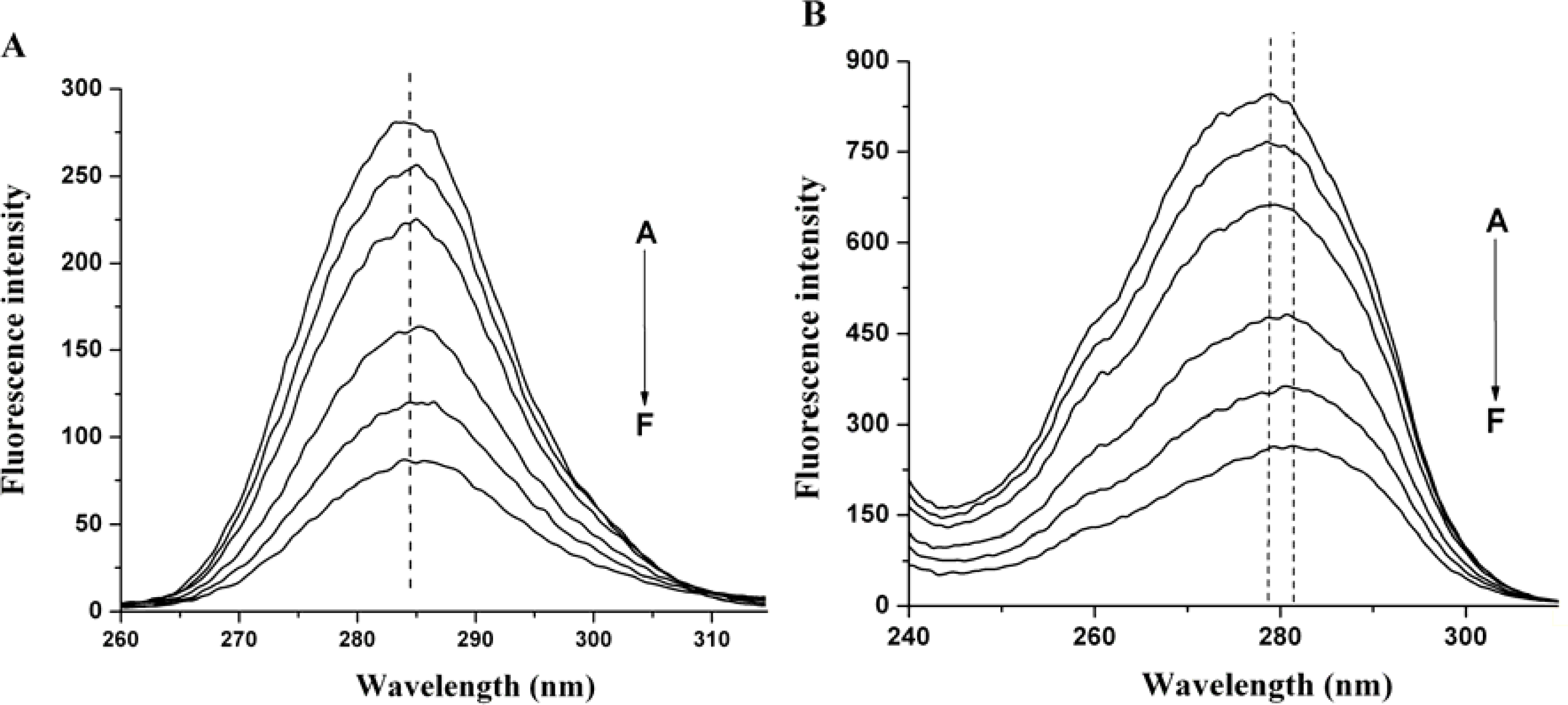

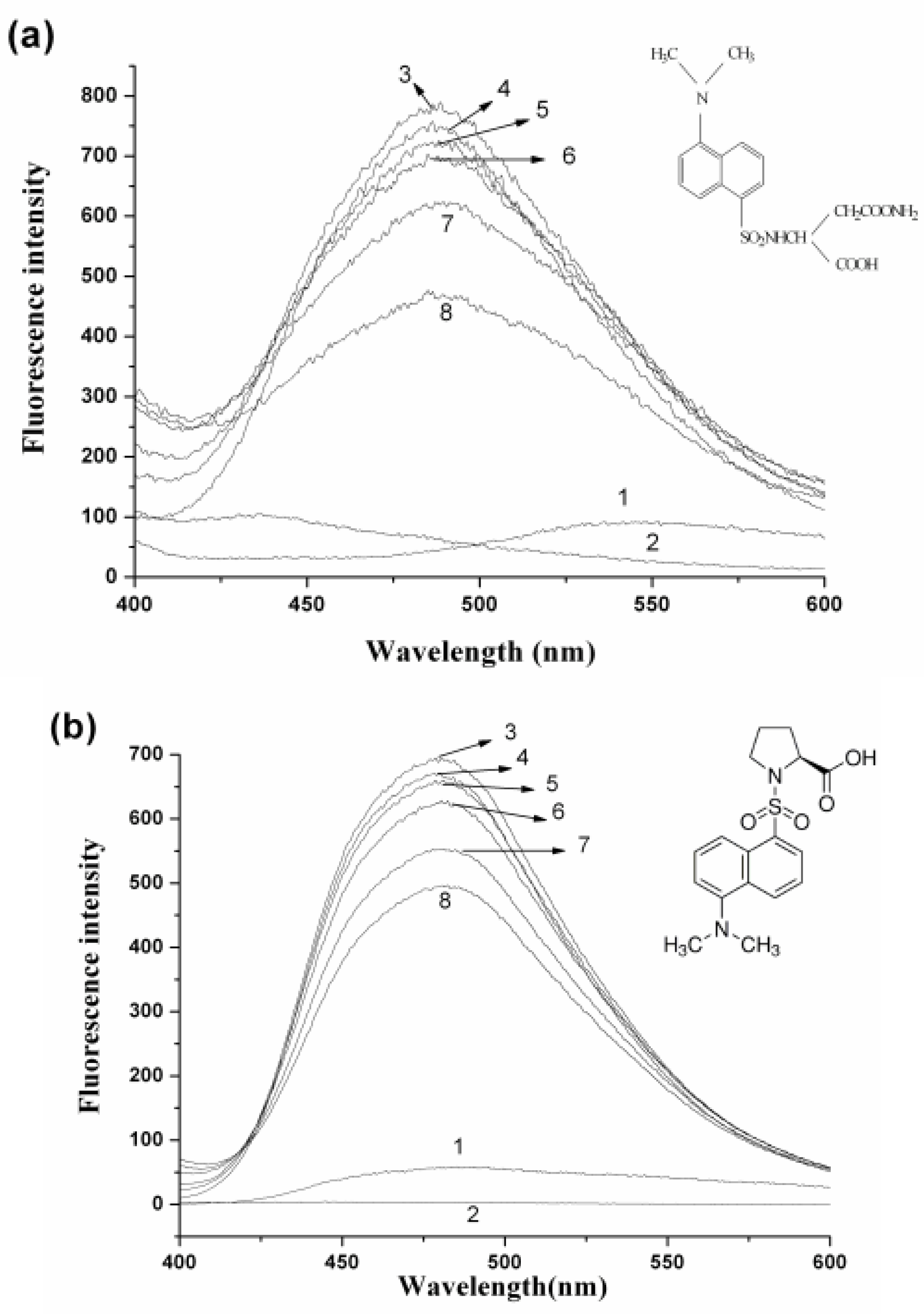

2.4. Interaction between HSA and nC60

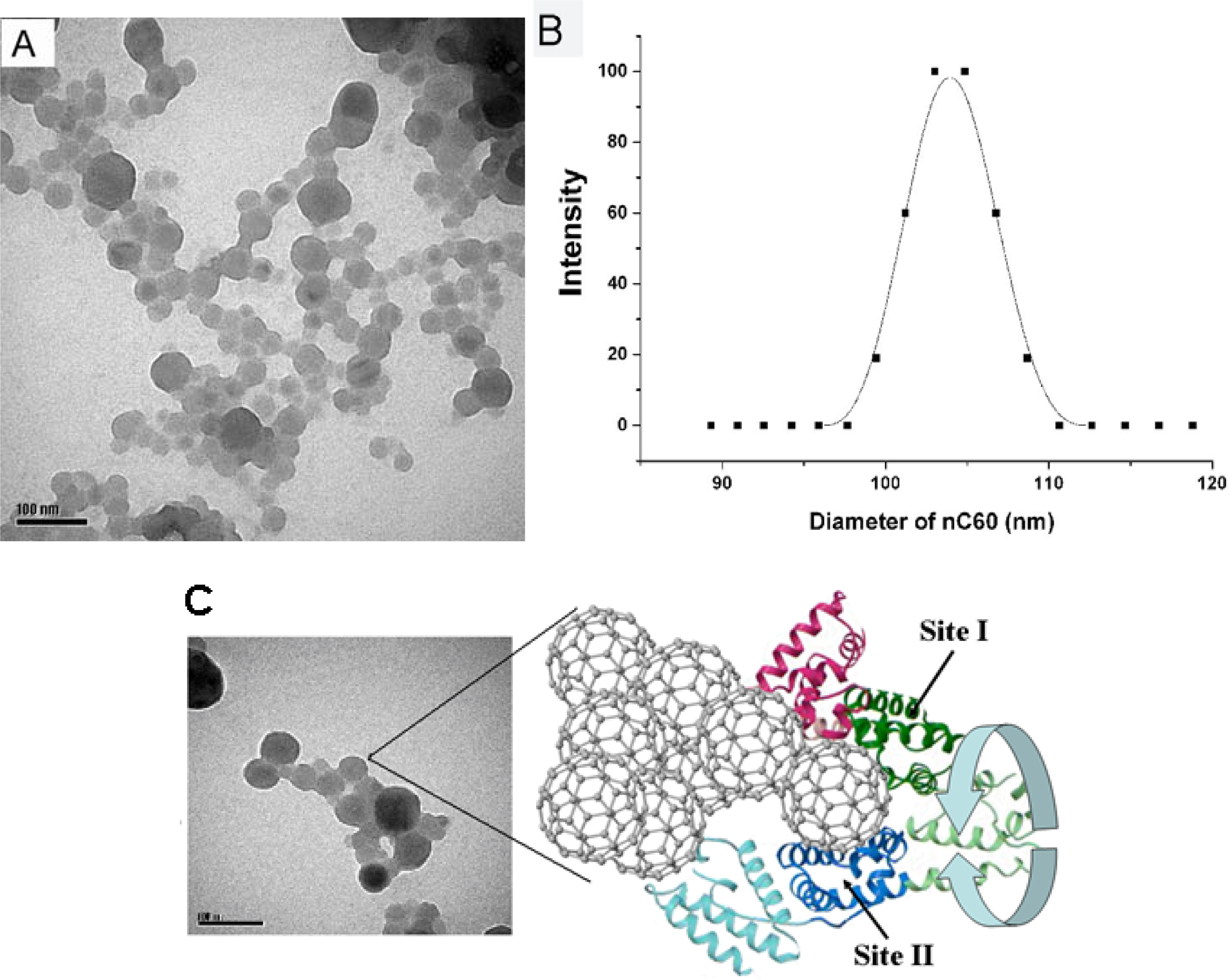

2.5. Representation of Interaction of HSA and nC60

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of Water-Soluble nC60

3.3. Methods

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Kroto, HW; Heath, JR; O’Brien, SC; Curl, RF; Smalley, RE. C60-Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, LJ. Medical applications of fullerenes and metallofullerenes. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 1999, 8, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Da Ros, T; Prato, M. Medicinal chemistry with fullerenes and fullerene derivatives. Chem. Commun 1999, 8, 663–669. [Google Scholar]

- Bakry, R; Vallant, RM; Najam-ul-Haq, M; Rainer, M; Szabo, Z; Huck, CW; Bonn, GK. Medicinal applications of fullerenes. Int. J. Nanomed 2007, 2, 639–649. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, JM; Tsyboulski, DA; Hartman, KB; Zakharian, TY; Marks, JW; Weisman, RB; Rosenblum, MG; Wilson, LJ. Fullerene (C60) immunoconjugates: Interaction of water-soluble C60 derivatives with the murine anti-gp240 melanoma antibody. Chem. Commun 2006, 28, 3004–3006. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharian, TY; Seryshev, A; Sitharaman, B; Gilbert, BE; Knight, V; Wilson, LJ. A fullerene-paclitaxel chemotherapeutic: Synthesis, characterization, and study of biological activity in tissue culture. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 12508–12509. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, G; Wang, H; Yan, L; Wang, X; Pei, R; Yan, T; Zhao, Y; Guo, X. Cytotoxicity of carbon nanomaterials: Single-wall nanotube, multi-wall nanotube and fullerene. Environ. Sci. Technol 2005, 39, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann, D. Solubillity of fullerenes C60 and C70 in seven normal alcohols and their deduced solubility in water. Fullerene Sci. Technol 1996, 4, 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, SH; DeCamp, DL; Sijbesma, R; Srdanov, G; Wudl, F; Kenyon, GL. Inhibition of the HIV-1 protease by fullerene derivatives: Model building studies and experimental verification. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115, 6506–6509. [Google Scholar]

- Marcorin, GL; Da Ros, T; Castellano, S; Stefancich, G; Bonin, I; Miertus, S; Prato, M. Design and synthesis of novel [60]fullerene derivatives as potential HIV aspartic protease inhibitors. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 3955–3958. [Google Scholar]

- Braden, BC; Goldbaum, FA; Chen, BX; Kirschner, AN; Wilson, SR; Erlanger, BF. X-ray crystal structure of an anti-Buckminsterfullerene antibody fab fragment: Biomolecular recognition of C(60). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12193–12197. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, XF; Shu, CY; Xie, L; Wang, CR; Zhang, YZ; Xiang, JF; Li, L; Tang, YL. protein conformation changes induced by a novel organophosphate-containing water-soluble derivative of a C60 fullerene nanoparticle. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 14327–14333. [Google Scholar]

- Belgorodsky, B; Fadeev, L; Ittah, V; Benyamini, H; Zelner, S; Huppert, D; Kotlyar, AB; Gozin, M. Formation and characterization of stable human serum albumin-tris-malonic acid [C60]fullerene complex. Bioconjug. Chem 2005, 16, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Brant, J; Lecoanet, H; Wiesner, MR. Aggregation and deposition characteristics of fullerene nanoparticles in aqueous systems. J. Nanopart. Res 2005, 7, 545–553. [Google Scholar]

- Scharff, P; Risch, K; Carta-Abelmann, L; Dmytruk, IM; Bilyi, MM; Golub, OA; Khavryuchenko, AV; Buzaneva, EV; Aksenov, VL; Avdeev, MV; et al. Structure of C60 fullerene in water: Spectroscopic data. Carbon 2004, 42, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X; Kan, AT; Tomson, MB. Naphtalene adsorption and desorption from aqueous C60 fullerene. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2004, 49, 675–683. [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi, S; Alargova, RG; Tsuji, K. Stable dispersions of fullerenes C60 and C70 in water. Preparation and characterization. Langmuir 2001, 17, 6013–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, L; Wang, Y; Jiang, J; Dong, S. pH-dependent protein conformational changes in albumin: gold nanoparticle bioconjugates: A spectroscopic study. Langmuir 2007, 23, 2714–2721. [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi, S; Yamazaki, T; Mukai, S; Usami, R; Horikoshi, K. Stabilization of C60 nanoparticles by protein adsorption and its implications for toxicity studies. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2007, 20, 854–858. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz, JR; Weber, G. Quenching of fluorescence by oxygen. Probe for structural fluctuations in macromolecules. Biochemistry 1973, 21, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar]

- Sudlow, G; Birkett, DJ; Wade, DN. The Characterization of two specific drug binding sites on human serum albumin. Mol. Pharmacol 1975, 11, 824–832. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, VT; Kuniyasu, A; Nakayama, H; Matsushita, Y; Hirono, S; Otagiri, M. Helix 6 of subdomain III A of human serum albumin is the region primarily photolabeled by ketoprofen, an arylpropionic acid NSAID containing a benzophenone moiety. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1434, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Benyamini, H; Shulman-Peleg, A; Wolfson, HJ; Belgorodsky, B; Fadeev, L; Gozin, M. Interaction of C60-Fullerene and Carboxyfullerene with proteins: Docking and binding site alignment. Bioconjug. Chem 2006, 17, 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaini, G; Ganazzoli, F. Simulation study of the interaction of some albumin subdomains with a flat graphite surface. Langmuir 2003, 19, 3403–3412. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M; Jiang, G; Yin, J; Wang, H. Inhibition of Taq polymerase activity by pristine fullerene nanoparticles can be mitigated by abundant proteins. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 1404–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Andrievsky, GV; Kosevich, MV; Vovk, OM; Shelkovsky, VS; Vashchenko, LA. On the production of an aqueous colloidal solution of fullerenes. J Chem Soc Chem Commun 1995, 1281–1282. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, M.; Liu, S.; Yin, J.; Wang, H. Interaction of Human Serum Album and C60 Aggregates in Solution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4964-4974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12084964

Song M, Liu S, Yin J, Wang H. Interaction of Human Serum Album and C60 Aggregates in Solution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2011; 12(8):4964-4974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12084964

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Maoyong, Shufang Liu, Junfa Yin, and Hailin Wang. 2011. "Interaction of Human Serum Album and C60 Aggregates in Solution" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 12, no. 8: 4964-4974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12084964