Poly[(3-hexylthiophene)-block-(3-semifluoroalkylthiophene)] for Polymer Solar Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

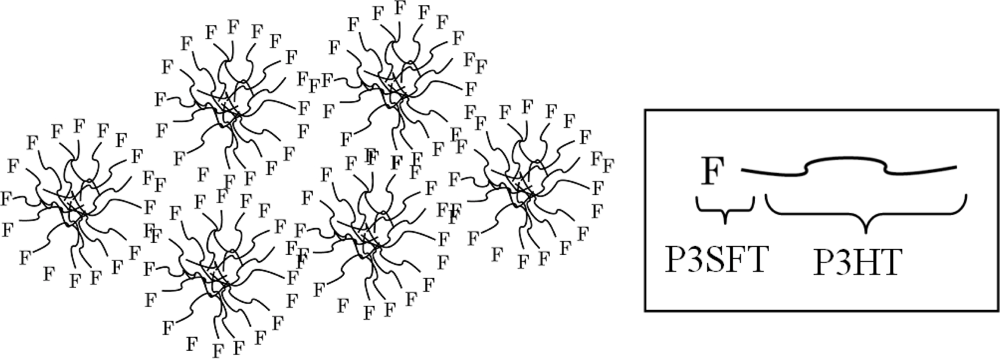

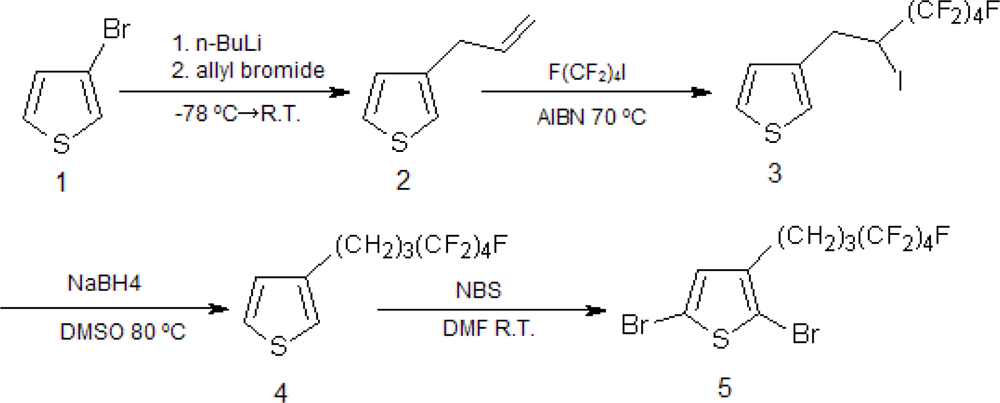

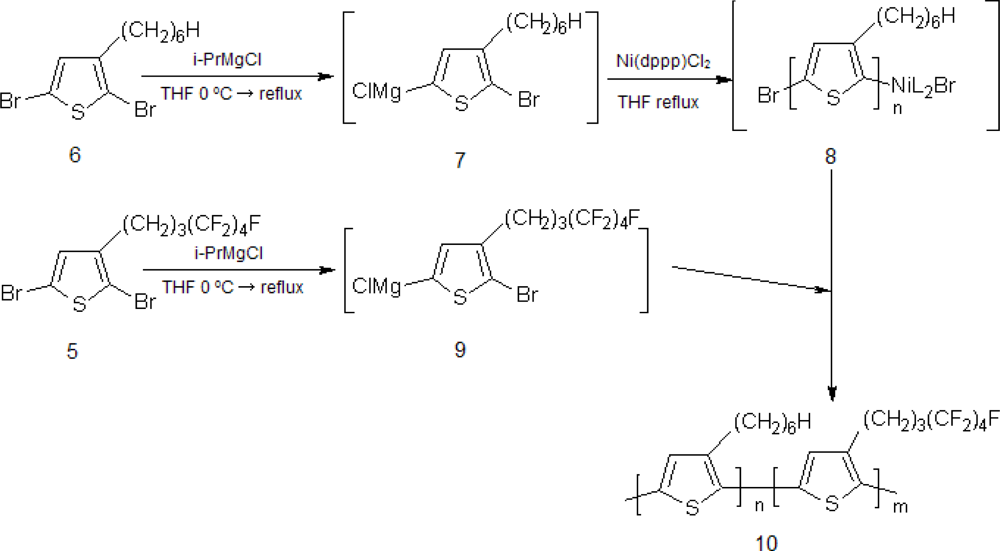

2.1. Synthesis of Poly[(3-hexylthiophene)-block-(3-(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)thiophene)], P(3HT-b-3SFT)

2.2. Polymer Characterization

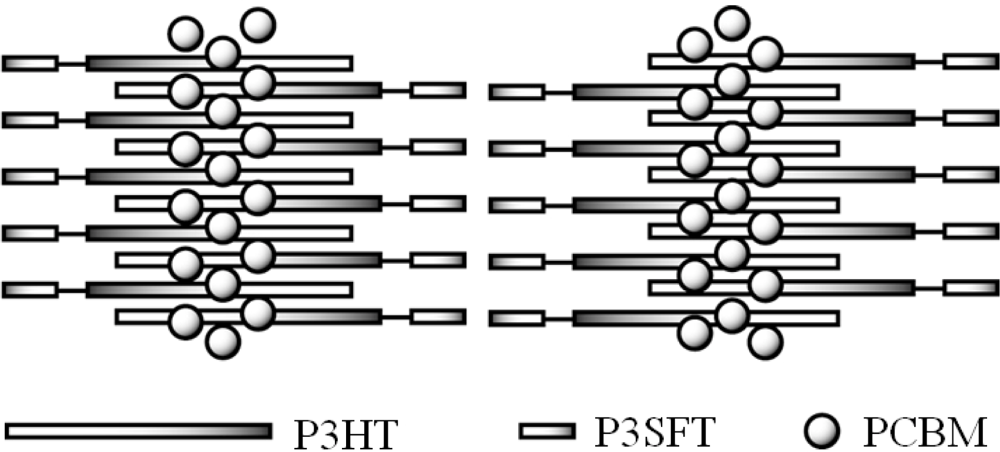

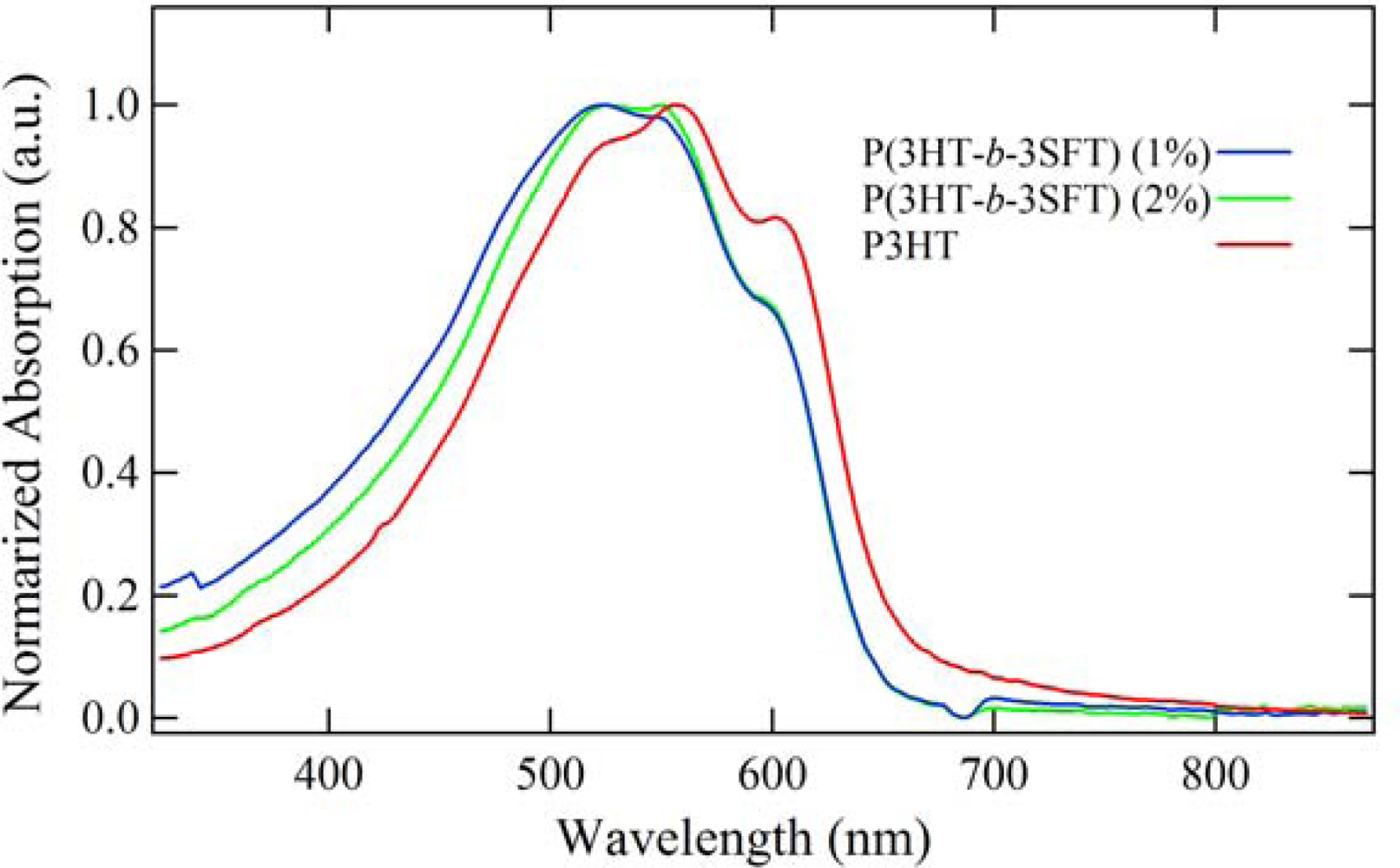

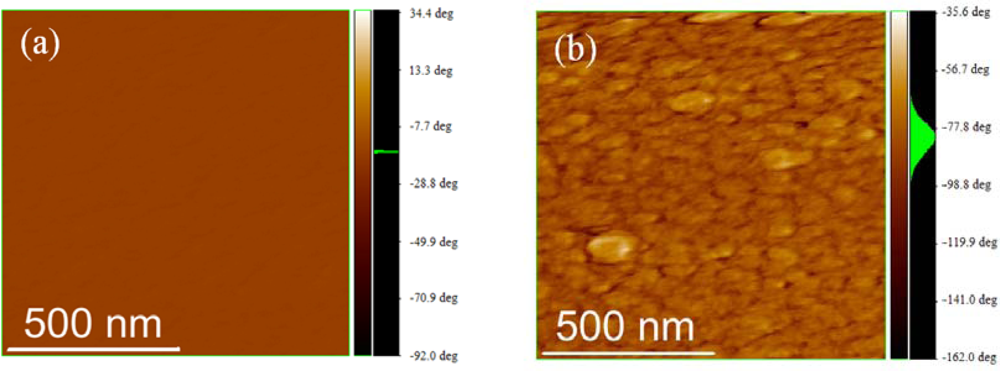

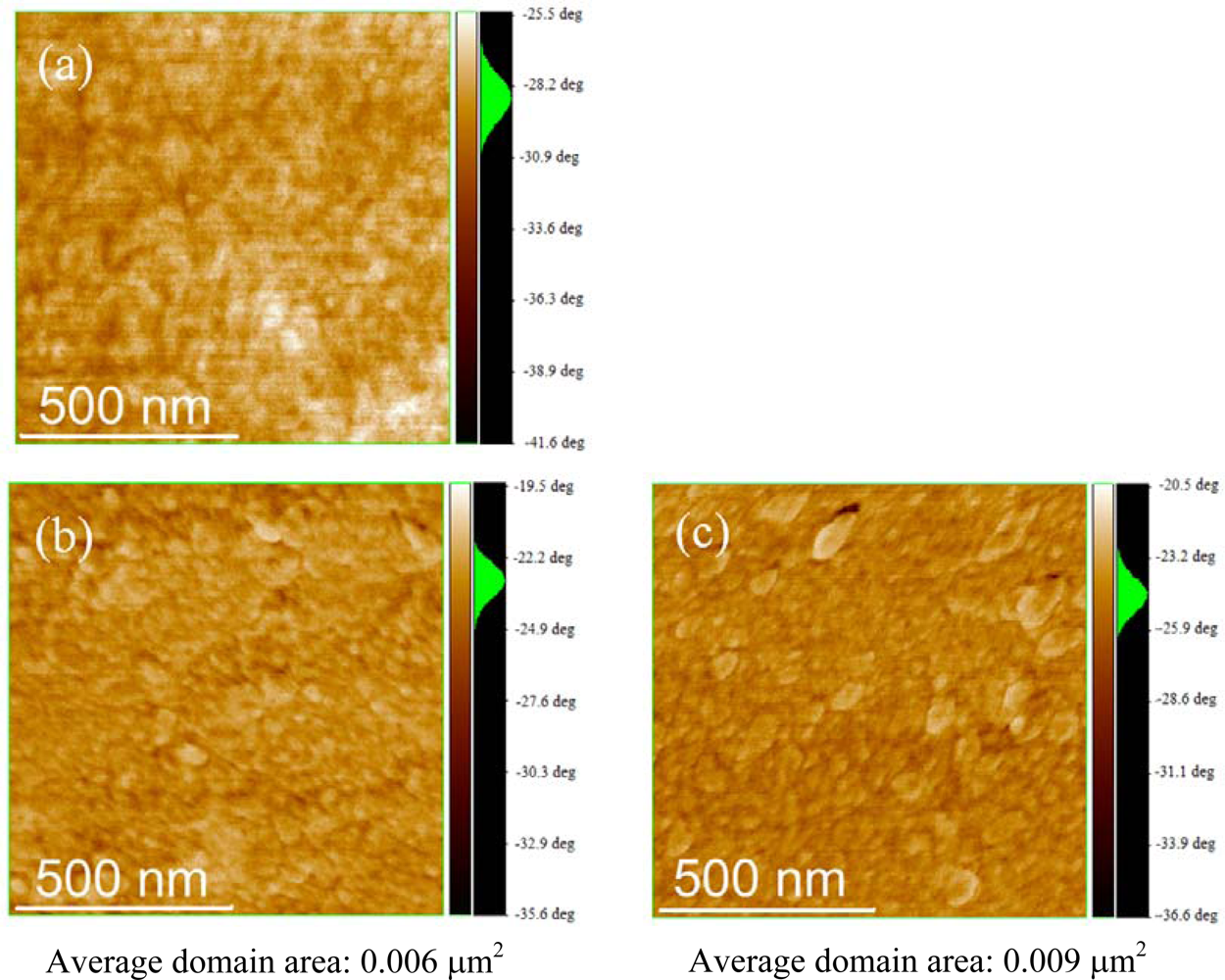

2.3. Film Characterization of Polymer

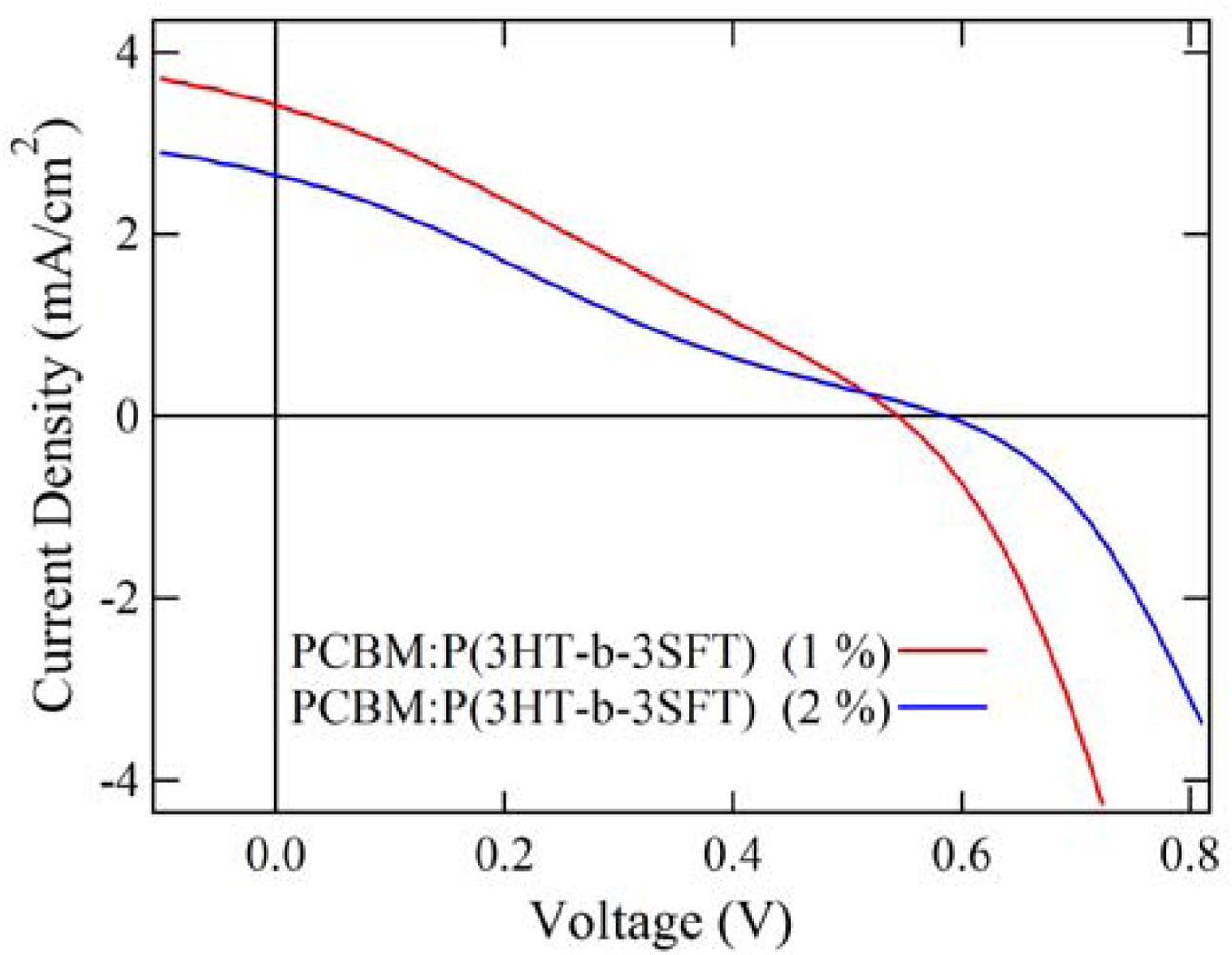

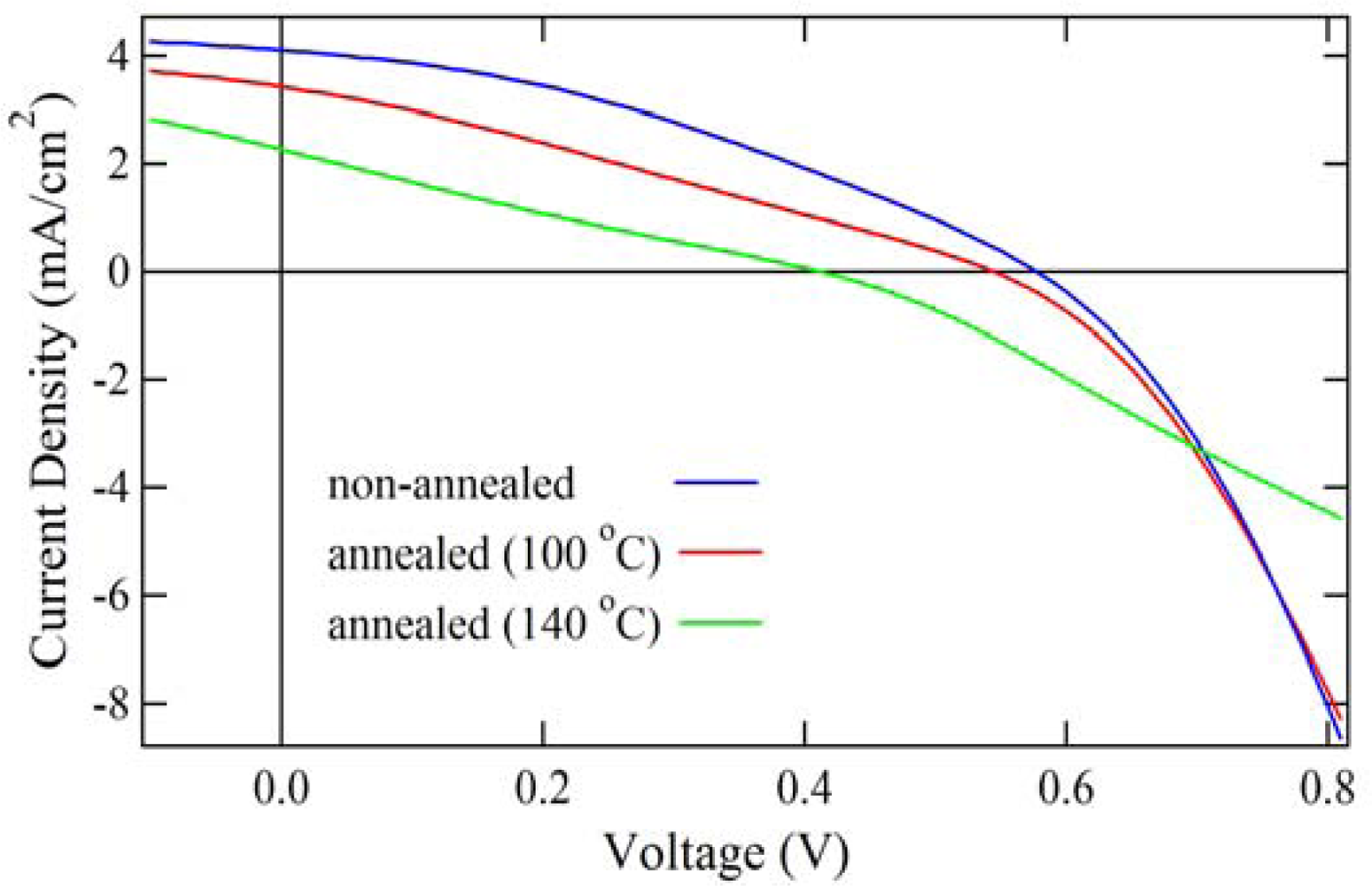

2.4. Properties of Photovoltaic Cells

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Material and Instrumentation

3.2. Synthesis of Poly(3-hexylthiophene)-b-poly(3-(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)thiophene) (10)

3.3. Film Preparation for Measurement of UV-Spectrum and AFM

3.4. Fabrication and Measurement of Solar Cells

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Sariciftci, NS; Smilowitz, L; Heeger, AJ; Wudl, F. Photoinduced Electron Transfer from a Conducting Polymer to Buckminsterfullerene. Science 1992, 258, 1474–1476. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G; Gao, J; Hummelen, JC; Wudl, F; Heeger, AJ. Polymer Photovoltaic Cells: Enhanced Efficiencies via a Network of Internal Donor-Acceptor Heterojunctions. Science 1995, 270, 1789–1791. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, SE; Brabec, CJ; Sariciftci, NS; Padinger, F; Fromherz, T; Hummelen, JC. 2.5% efficient organic plastic solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett 2001, 78, 841. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Y; Yamada, I; Takagi, S; Takasu, A; Soga, T; Jimbo, T. Influence of Structure and C60 Composition on Properties of Blends and Bilayers of Organic Donor-Acceptor Polymer/C60 Photovoltaic Devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys 2005, 44, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, BC; Fréchet, J. Polymer-Fullerene Composite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y; Xu, Z; Xia, J; Tsai, S; Wu, Y; Li, G; Ray, C; Yu, L. For the Bright Future-Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells with Power Conversion Efficiency of 7.4%. Adv. Mater 2010, 22, E135–E138. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L; Hong, Z; Li, G; Yang, Y. Recent Progress in Polymer Solar Cells: Manipulation of Polymer:Fullerene Morphology and the Formation of Efficient Inverted Polymer Solar Cells. Adv. Mater 2009, 21, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, H; Sariciftci, NS. Organic solar cells: An overview. J. Mater. Res 2004, 19, 1924–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X; Loos, J; Veenstra, SC; Verhees, WJH; Wienk, MM; Kroon, JM; Michels, MAJ; Janssen, RAJ. Nanoscale Morphology of High-Performance Polymer Solar Cells. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 579–583. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, JK; Ma, WL; Brabec, CJ; Yuen, J; Moon, JS; Kim, JY; Lee, K; Bazan, GC; Heeger, AJ. Processing Additives for Improved Efficiency from Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 3619–3623. [Google Scholar]

- Sivula, K; Ball, Z; Watanabe, N; Fréchet, J. Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymer Compatibilizers and Their Effect on the Morphology and Performance of Polythiophene:Fullerene Solar Cells. Adv. Mater 2006, 18, 206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, JU; Cirpan, A; Emrick, T; Russell, TP; Jo, WH. Synthesis and photophysical property of well-defined donor-acceptor diblock copolymer based on regioregular poly(3-hexylthiophene) and fullerene. J. Mater. Chem 2009, 19, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q; Cirpan, A; Russell, TP; Emrick, T. Donor-Acceptor Poly(thiophene-block-perylene diimide) Copolymers: Synthesis and Solar Cell Fabrication. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Ohshimizu, K; Ueda, M. Well-Controlled Synthesis of Block Copolythiophenes. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5289–5294. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y; Tajima, K; Hirota, K; Hashimoto, K. Synthesis of All-Conjugated Diblock Copolymers by Quasi-Living Polymerization and Observation of Their Microphase Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 7812–7813. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y; Tajima, K; Hashimoto, K. Nanostructure Formation in Poly(3-hexylthiophene-block-3-(2-ethylhexyl)thiophene)s. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 7008–7015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P; Ren, G; Li, C; Mezzenga, R; Jenekhe, SA. Crystalline Diblock Conjugated Copolymers:Synthesis, Self-Assembly, and Microphase Separation of Poly(3-butylthiophene)-b-poly(3-octylthiophene). Macromolecules 2009, 42, 2317–2320. [Google Scholar]

- Chueh, C; Higashihara, T; Tsai, J; Ueda, M; Chen, W. All-conjugated diblock copolymer of poly(3-hexylthiophene)-block-poly(3-phenoxymethylthiophene) for field-effect transistor and photovoltaic applications. Org. Electron 2009, 10, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P; Ren, G; Kim, FS; Li, C; Mezzenga, R; Jenekhe, SA. Poly(3-hexylthiophene)-b-poly(3-cyclohexylthiophene):Synthesis, microphase separation, thin-film transistors, and photovoltaic applications. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2010, 48, 614–626. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T; Hayakawa, Y. Fluorine-Based Crystal Engineering. Fluor.-Contain. Synthons 2005, 29, 498–513. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T; Hayakawa, Y; Yasuda, N; Uekusa, H; Ohashi, Y. A Hydro-Fluoro Hybrid Compound, Hermaphrodite, Is Fluorophilic or Fluorophobic? A New Concept for the Fluorine-Based Crystal Engineering. Curr. Fluoroorg. Chem 2007, 10, 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X; Tyson, JC; Middlecoff, JS; Collard, DM. Synthesis and Oxidative Polymerization of Semifluoroalkyl-Substituted Thiophenes. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 4232–4239. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe, RS; Ewbank, PC; Liu, J; Zhai, L; McCullough, RD. Regioregular, Head-to-Tail Coupled Poly(3-alkylthiophenes) Made Easy by the GRIM Method: Investigation of the Reaction and the Origin of Regioselectivity. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 4324–4333. [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoshi, R; Yokoyama, A; Yokozawa, T. Catalyst-Transfer Polycondensation. Mechanism of Ni-Catalyzed Chain-Growth Polymerization Leading to Well-Defined Poly(3-hexylthiophene). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 17542–17547. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B; Watt, S; Hong, M; Domercq, B; Sun, R; Kippelen, B; Collard, DM. Synthesis, Properties, and Tunable Supramolecular Architecture of Regioregular Poly(3-alkylthiophene)s with Alternating Alkyl and Semifluoroalkyl Substituents. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5156–5165. [Google Scholar]

- Sukeguchi, D; Singh, SP; Reddy, MR; Yoshiyama, H; Afre, RA; Hayashi, Y; Inukai, H; Soga, T; Nakamura, S; Shibata, N; Toru, T. New diarylmethanofullerene derivatives and their properties for organic thin-film solar cells. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2009, 5, 7. [Google Scholar]

| Polymer | Mn | Mw | Mw/Mn |

|---|---|---|---|

| P(3HT-b-3SFT) (1 mol% Ni(dppp)Cl2) | 25,600 | 36,200 | 1.4 |

| P(3HT-b-3SFT) (2 mol% Ni(dppp)Cl2) | 10,500 | 13,500 | 1.2 |

| Polymer | Ra (nm) | RMS (nm) | Average Domain Area in Phase Image (μm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT | 1.22 | 1.51 | - |

| P(3HT-b-3SFT) (1 mol% Ni(dppp)Cl2) | 2.03 | 2.80 | 0.050 |

| P(3HT-b-3SFT) (2 mol% Ni(dppp)Cl2) | 1.98 | 2.58 | 0.019 |

| Materials | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF | Eff (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCBM:P(3HT-b-3SFT) (1 mol% Ni(dppp)Cl2) | 0.54 | 3.42 | 0.28 | 0.52 |

| PCBM:P(3HT-b-3SFT) (2 mol% Ni(dppp)Cl2) | 0.59 | 2.65 | 0.23 | 0.35 |

| Annealing Temp | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF | Eff (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R.T. | 0.58 | 4.10 | 0.35 | 0.84 |

| 100 °C | 0.54 | 3.42 | 0.28 | 0.52 |

| 140 °C | 0.41 | 2.27 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamada, I.; Takagi, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Soga, T.; Shibata, N.; Toru, T. Poly[(3-hexylthiophene)-block-(3-semifluoroalkylthiophene)] for Polymer Solar Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 5027-5039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11125027

Yamada I, Takagi K, Hayashi Y, Soga T, Shibata N, Toru T. Poly[(3-hexylthiophene)-block-(3-semifluoroalkylthiophene)] for Polymer Solar Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2010; 11(12):5027-5039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11125027

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamada, Ichiko, Koji Takagi, Yasuhiko Hayashi, Tetsuo Soga, Norio Shibata, and Takeshi Toru. 2010. "Poly[(3-hexylthiophene)-block-(3-semifluoroalkylthiophene)] for Polymer Solar Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11, no. 12: 5027-5039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11125027