Molecular Diversity by Olefin Cross-Metathesis on Solid Support. Generation of Libraries of Biologically Promising β-Lactam Derivatives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

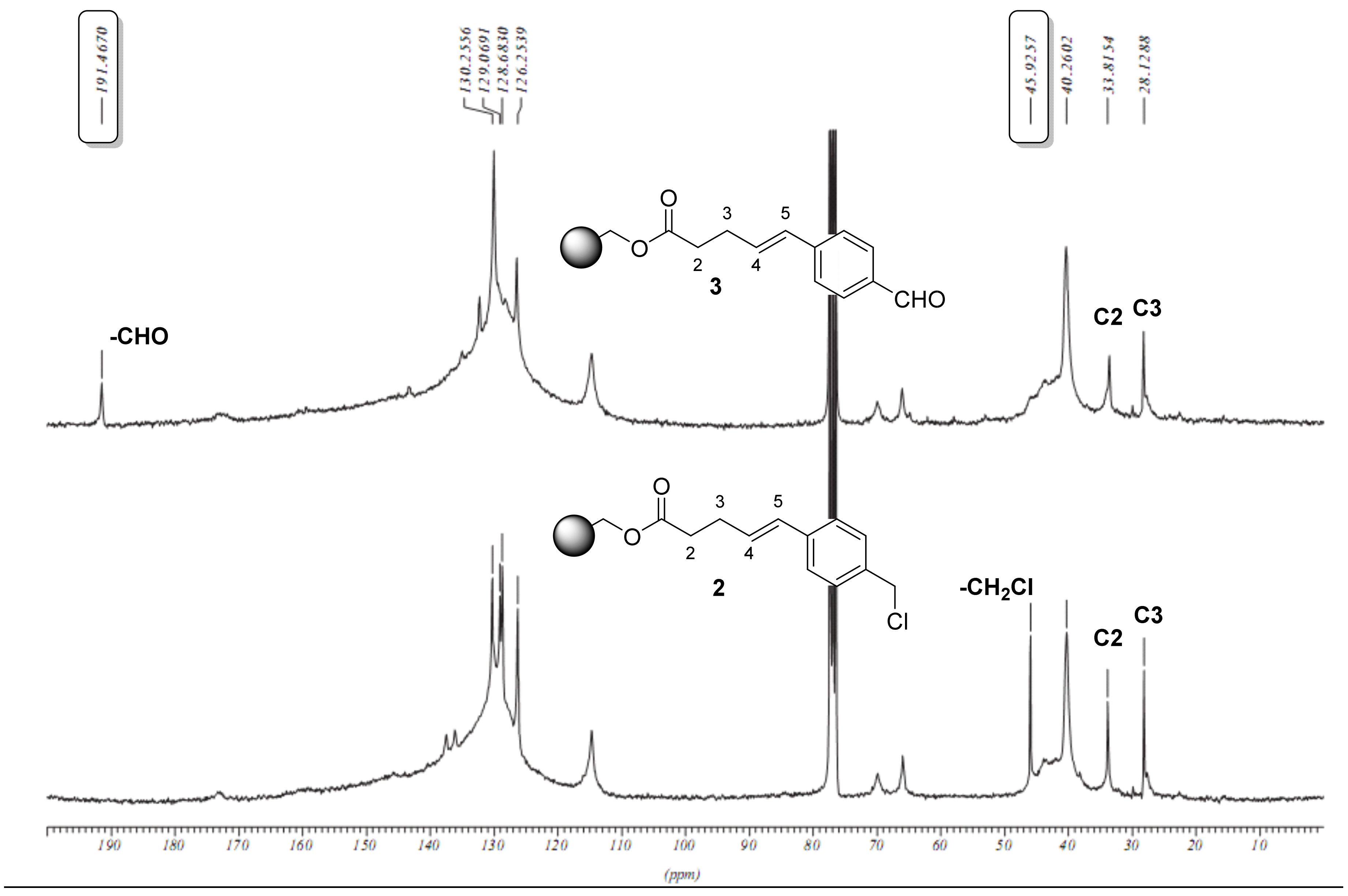

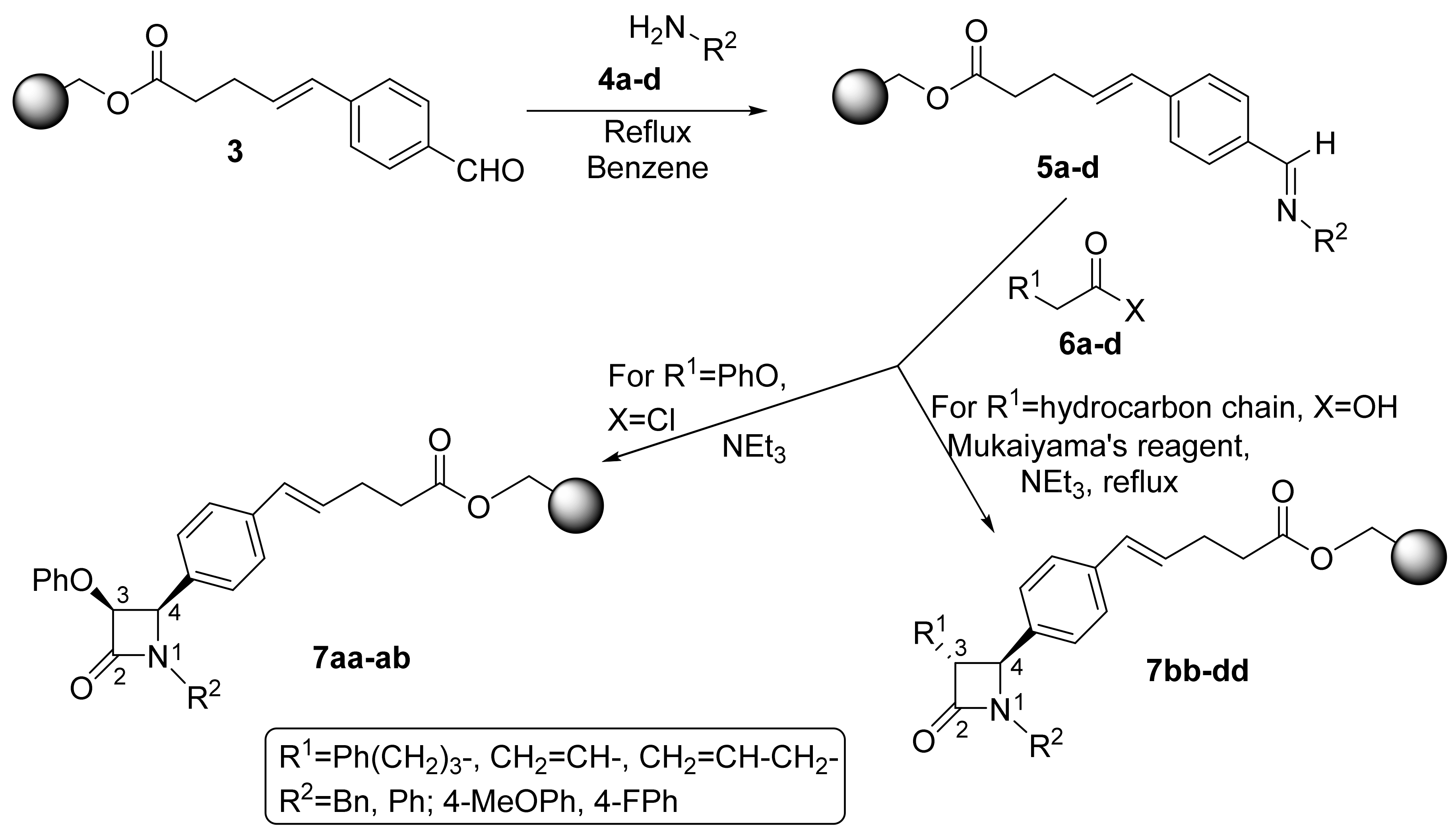

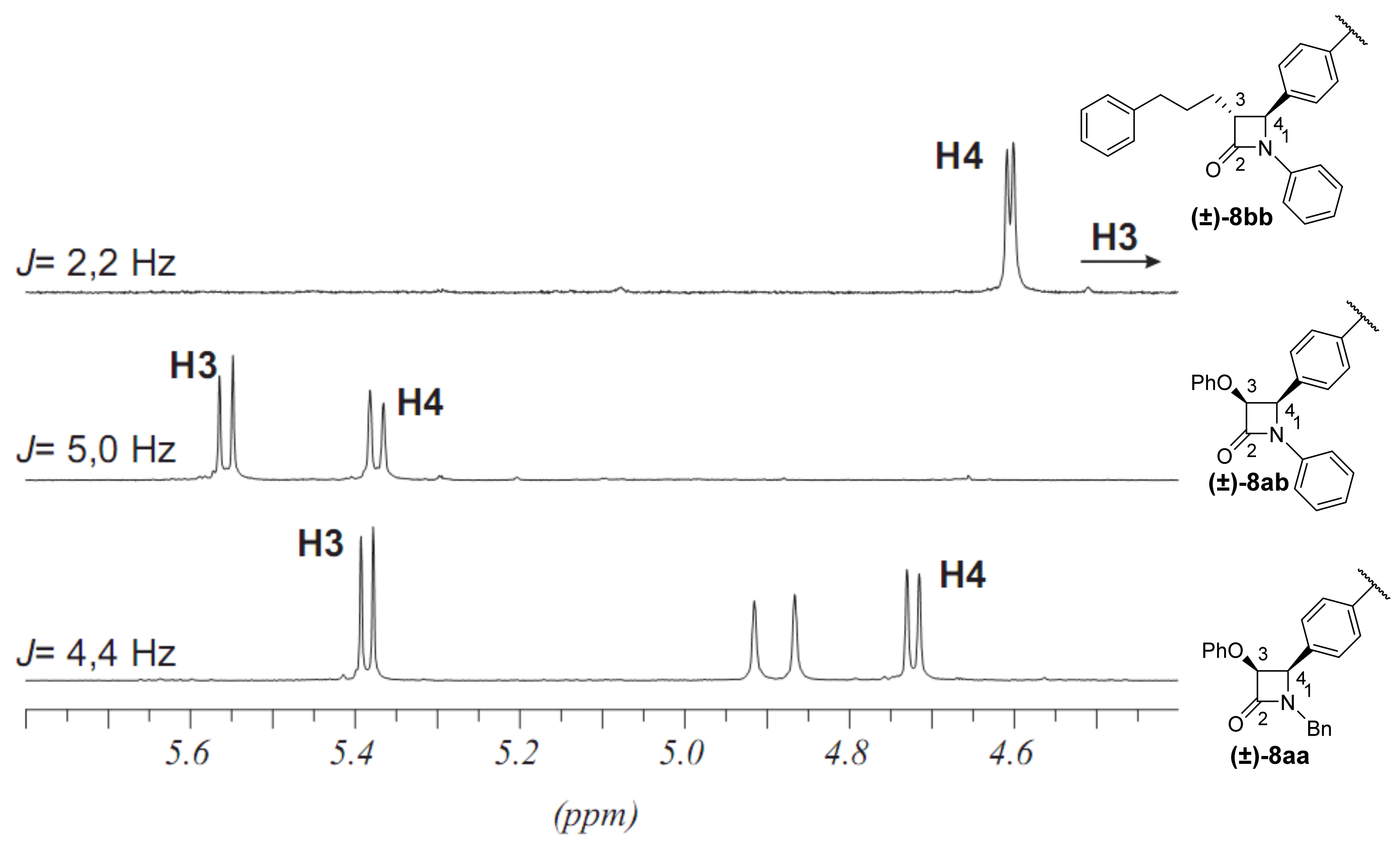

2.1. Primary β-Lactam Library

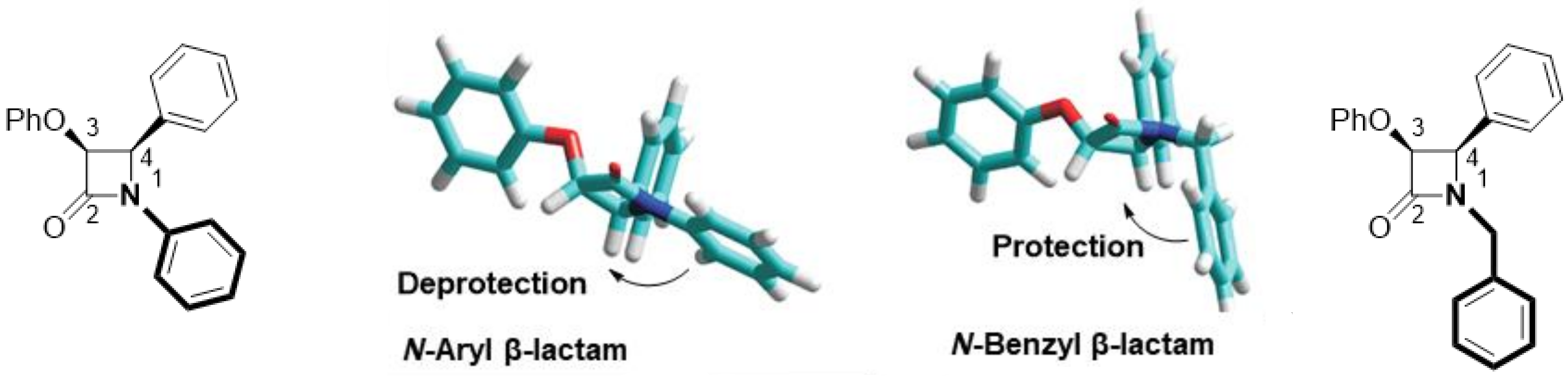

2.2. Secondary β-Lactam Libraries

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

3.2. Instrumental and Physical Data

3.3. Synthetic Procedures

3.4. Analytical Data

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Note

- Arya, N.; Jagdale, A.Y.; Patil, T.A.; Yeramwar, S.S.; Holikatti, S.S.; Dwivedi, J.; Shishoo, C.J.; Jain, K.S. The chemistry and biological potential of azetidin-2-ones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 74, 619–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testero, S.A.; Fisher, J.F.; Mobashery, S. β-Lactam Antibiotics in Burger's Medicinal Chemistry, Drug Discovery and Development; Abraham, D.J., Rotella, D.P., Eds.; Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Adlington, R.M.; Baldwin, J.E.; Chen, B.; Cooper, S.L.; McCoull, W.; Pritchard, G.J.; Howe, T.J.; Becker, G.W.; Hermann, R.B.; McNulty, A.M.; et al. Design and synthesis of novel monocyclic β-lactam inhibitors of prostate specific antigen. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997, 7, 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, R.; Benaglia, M.; Cinquini, M.; Cozzi, F.; Puglisi, A. Efficient and highly stereoselective synthesis of a β-Lactam inhibitor of the serine protease prostate-specific antigen. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, R.; Benaglia, M.; Cinquini, M.; Cozzi, F.; Maggioni, F.; Puglisi, A. Efficient synthesis of an enantiopure β-lactam as an advanced precursor of thrombin and tryptase inhibitors. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 2952–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borthwick, A.D.; Weingarten, G.; Haley, T.M.; Tomaszewski, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, Z.; Bedard, J.; Jih, H.; Yuen, L.; Mansour, T.S. Design and synthesis of monocyclic β-lactams as mechanism-based inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainelli, G.; Galletti, P.; Garbisa, S.; Giacomini, D.; Sartor, L.; Quintavalla, A. 4-Alkyliden-β-lactams conjugated to polyphenols: Synthesis and inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 6120–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setti, E.L.; Davis, D.; Chung, T.; McCarter, J. 3,4-Disubstituted azetidinones as selective inhibitors of the cysteine protease cathepsin K. Exploring P2 elements for selectivity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 2051–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.E.; Guo, D.; Thomas, G.; Reddy, A.V.N.; Kaleta, J.; Purisima, E.; Menard, R.; Micetich, R.G.; Singh, R. 3-Acylamino-azetidin-2-one as a novel class of cysteine proteases inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feledziak, M.; Michaux, C.; Urbach, A.; Labar, G.; Muccioli, G.G.; Lambert, D.M.; Marchand-Brynaert, J. β-Lactams derived from a carbapenem chiron are selective inhibitors of human fatty acid amide hydrolase versus human monoacylglycerol lipase. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7054–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornier, P.G.; Delpiccolo, C.M.L.; Mascali, F.C.; Boggián, D.B.; Mata, E.G.; Cárdenas, M.G.; Blank, V.C.; Roguin, L.P. In vitro anticancer activity and SAR studies of triazolyl aminoacyl (peptidyl) penicillins. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggián, D.B.; Cornier, P.G.; Mata, E.G.; Blank, V.C.; Cárdenas, M.G.; Roguin, L.P. A solid-and solution-phase-based library of 2β-methyl substituted penicillin derivatives and their effects on growth inhibition of tumor cell lines. MedChemComm 2015, 6, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veinberg, G.; Vorona, M.; Shestakova, I.; Kanepe, I.; Zharkova, O.; Mezapuke, R.; Turovskis, I.; Kalvinsh, I.; Lukevics, E. Synthesis and antitumor activity of selected 7-alkylidene substituted cephems. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, I.; Becker, F.F.; Banik, B.K. Stereoselective synthesis of β-lactams with polyaromatic imines: Entry to new and novel anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Sachdeva, S.; Raj, R.; Kumar, V.; Mahajan, M.P.; Nasser, S.; Vivas, J.; Gut, L.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Feng, T.; et al. Antiplasmodial and cytotoxicity evaluation of 3-functionalized 2-azetidinone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 4561–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothstein, J.D.; Patel, S.; Regan, M.R.; Haenggeli, C.; Huang, Y.H.; Bergles, D.E.; Jin, L.; Dykes-Hoberg, M.; Vidensky, S.; Chung, D.S.; et al. β-Lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature 2005, 433, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.F.; Shen, L.; Zhang, H.Y. β-Lactam antibiotics are multipotent agents to combat neurological diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 333, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, T.; Kværnø, L.; Werder, M.; Hauser, H.; Carreira, E.M. Heterocyclic ring scaffolds as small-molecule cholesterol absorption inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 3514–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, D.K.; Shaikh, A.Y.; Pavase, L.S.; Gumaste, V.K.; Deshmukh, A.R.A.S. Stereoselective synthesis of 3-alkylidene/alkylazetidin-2-ones from azetidin-2,3-diones. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 2524–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, D.A. β-Lactam cholesterol absorption inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 1873–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Fu, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Bai, X. Ezetimibe analogs with a reorganized azetidinone ring: Design, synthesis, and evaluation of cholesterol absorption inhibitions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, P.P.; Farnier, M.; Tomassini, J.E.; Foody, J.M.; Tershakovec, A.M. Statin combination therapy and cardiovascular risk reduction. Future Cardiol. 2016, 12, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, E.; López Ortiz, F.; del Pozo, C.; Peralta, E.; Macias, A.; González, J. Spiro β-lactams as β-turn mimetics. Design, synthesis, and NMR conformational analysis. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 6333–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomo, C.; Aizpurua, J.M.; Benito, A.; Galarza, R.; Khamrai, U.K.; Vazquez, J.; de Pascual-Teresa, B.; Nieto, P.M.; Linden, A. α-Alkyl-α-Amino-β-Lactam Peptides: Design, Synthesis, and Conformational Features. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3056–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malachowski, W.P.; Tie, C.; Wang, K.; Broadrup, R.L. The synthesis of azapeptidomimetic β-lactam molecules as potential protease inhibitors. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 8962–8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

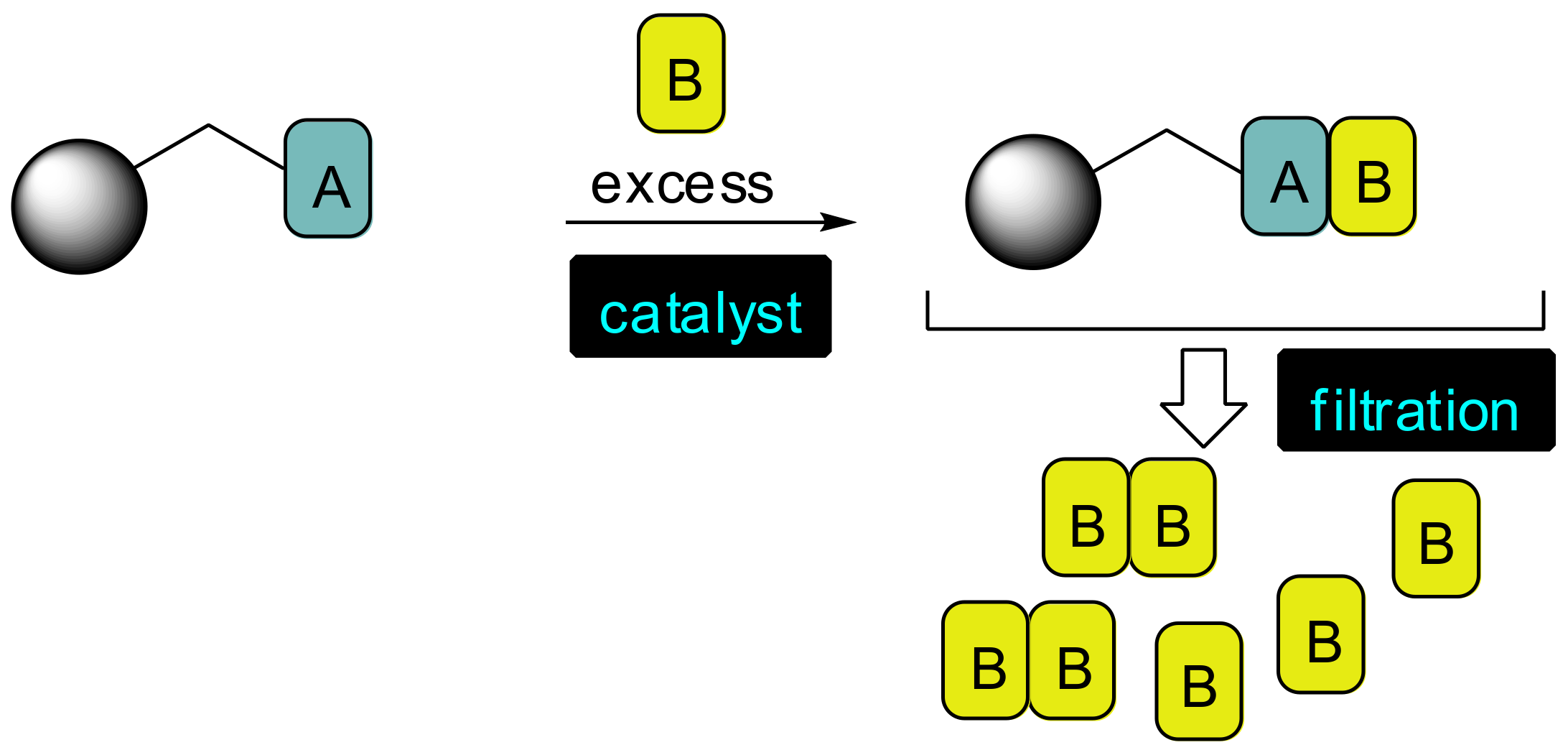

- Young, D.D.; Deiters, A. Solid-Phase Organic Synthesis: Concepts, Strategies, and Applications; Toy, P.H., Lam, Y., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 171–201. [Google Scholar]

- Testero, S.A.; Mata, E.G. Synthesis of 3-(aryl) alkenyl-β-lactams by an efficient application of olefin cross-metathesis on solid support. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4783–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, A.L.; Koide, K. Solid-phase olefin cross-metathesis promoted by a linker. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5235–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, L.; Testero, S.A.; Mata, E.G. Versatile and efficient solid-supported synthesis of C3-anchored monocyclic β-lactam derivatives. J. Comb. Chem. 2007, 9, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghalit, N.; Kemmink, J.; Hilbers, H.W.; Versluis, C.; Rijkers, D.T.S.; Liskamp, R.M.J. Step-wise and pre-organization induced synthesis of a crossed alkene-bridged nisin Z DE-ring mimic by ring-closing metathesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, L.; Mata, E.G. Solid-supported cross-metathesis and a formal alkane metathesis for the generation of biologically relevant molecules. ACS Comb. Sci. 2015, 17, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poeylaut-Palena, A.A.; Testero, S.A.; Mata, E.G. Solid-supported cross metathesis and the role of the homodimerization of the non-immobilized olefin. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2024–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poeylaut-Palena, A.A.; Mata, E.G. Solid-phase cross-metathesis: The effect of the non-immobilized olefin and the precatalyst on the intrasite interference. Arkivoc 2010, 2010, 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Yellol, G.S.; Sun, C.-M. Solid-Supported Synthesis Green Techniques for Organic Synthesis and Medicinal Chemistry; Zhang, W., Cue, B.W., Jr., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

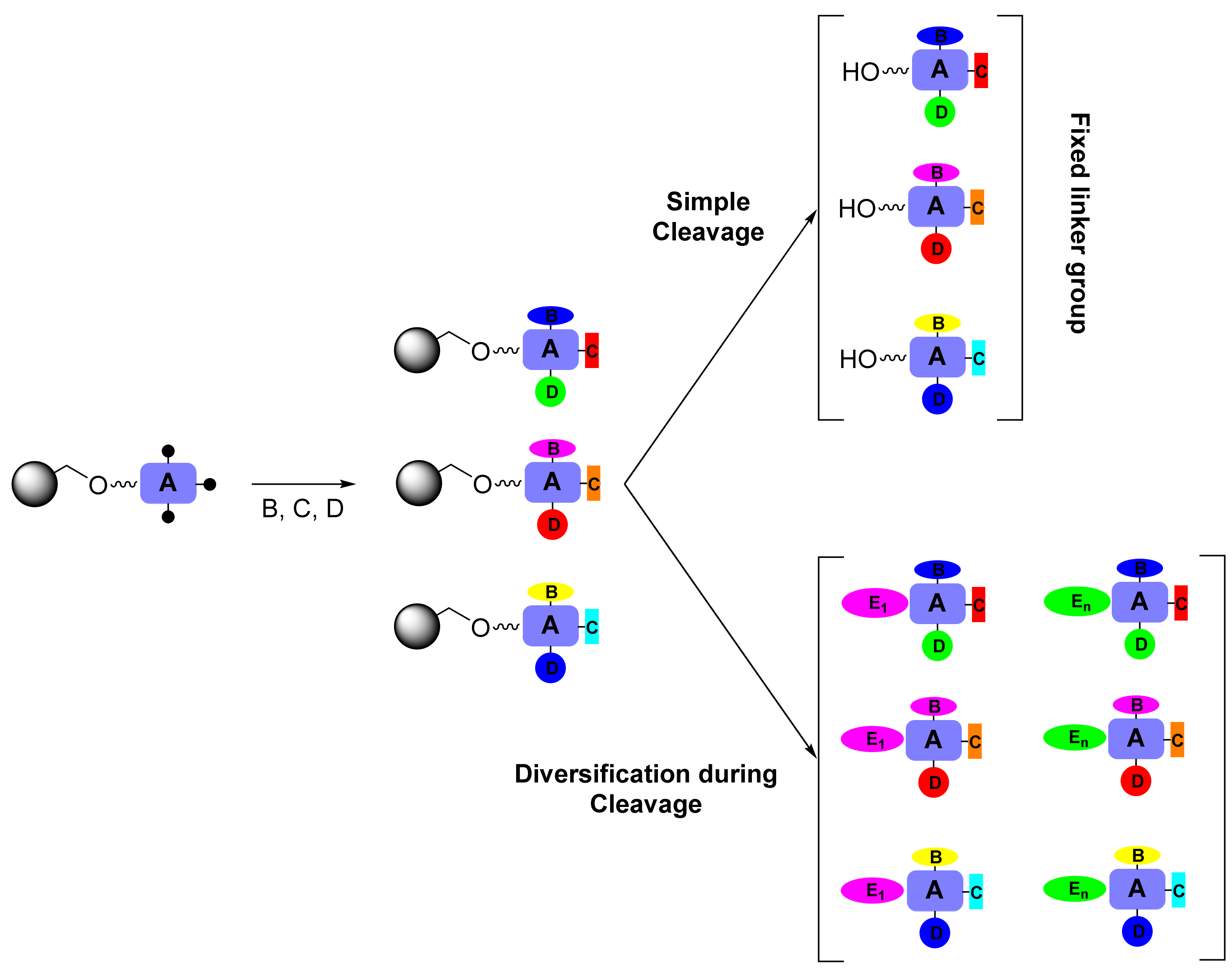

- Galloway, W.R.J.D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Spring, D.R. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a tool for the discovery of novel biologically active small molecules. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’ Connor, C.J.; Laraia, L.; Spring, D.R. Chemical genetics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4332–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckmann, H.; O’ Connor, C.J.; Spring, D.R. Diversity-oriented synthesis: Producing chemical tools for dissecting biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4444–4456. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, S.L.; Burke, M.D. A planning strategy for diversity-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Delpiccolo, C.M.; Testero, S.A.; Leyes, F.N.; Boggián, D.B.; Camacho, C.M.; Mata, E.G. Stereoselective, solid phase-based synthesis of trans 3-alkyl-substituted β-lactams as analogues of cholesterol absorption inhibitors. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 10780–10786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberger, P.H. The Logic of Automated Glycan Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1450–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Current manuscript is a full paper partially based on extension of the short communication: Poeylaut-Palena, A.A.; Mata, E.G. Cross metathesis on solid support. Novel strategy for the generation of β-lactam libraries based on a versatile and multidetachable olefin linker. J. Comb. Chem. 2009, 11, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres, J.T.; Mann, C.K. Some chemical reactions of poly(p-chloromethylstyrene) resin in dimethylsulfoxide. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Lett. Ed. 1965, 3, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpiccolo, C.M.L.; Mata, E.G. Stereoselective solid-phase synthesis of 3,4-substituted azetidinones as key intermediates for mono-and multicyclic β-lactam antibiotics and enzyme inhibitors. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2002, 13, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpiccolo, C.M.L.; Fraga, M.A.; Mata, E.G. An efficient, stereoselective solid-phase synthesis of β-lactams using Mukaiyama’s salt for the staudinger reaction. J. Comb. Chem. 2003, 5, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpiccolo, C.M.L.; Mendez, L.; Fraga, M.A.; Mata, E.G. Exploring the solid-phase synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted β-lactams: Scope and limitations. J. Comb. Chem. 2005, 7, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decazes, J.; Luche, J.L.; Kagan, H.B. Cycloaddition des cetenes sur les bases de schiff III: Determination par R.M.N. de la configuration de triphenyl 1-3-4, alcoyl 3, azetidinones 2. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970, 11, 3661–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Liang, Y.; Xu, J. Origin of the relative stereoselectivity of the β-lactam formation in the Staudinger reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6060–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Jiao, L.; Du, D.M.; Xu, J. Do reaction conditions affect the stereoselectivity in the staudinger reaction? J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 6983–6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Zoebisch, E.G.; Healy, E.F.; Stewart, J.J.P. Development and use of quantum mechanical molecular models. 76. AM1: A new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 3902–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.K.; Choi, T.L.; Sanders, D.P.; Grubbs, R.H. A general model for selectivity in olefin cross metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11360–11370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegas-Junior, C.; Danuello, A.; da Silva Bolzani, V.; Barreiro, E.J.; Fraga, C.A. Molecular hybridization: A useful tool in the design of new drug prototypes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1829–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guantai, E.M.; Ncokazi, K.; Egan, T.J.; Gut, J.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Smith, P.J.; Chibale, K. Design, synthesis and in vitro antimalarial evaluation of triazole-linked chalcone and dienone hybrid compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 8243–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, M. Hybrid molecules incorporating natural products: Applications in cancer therapy, neurodegenerative disorders and beyond. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’hooghe, M.; Mollet, K.; De Vreese, R.; Jonckers, T.H.; Dams, G.; De Kimpe, N. Design, synthesis, and antiviral evaluation of purine-β-lactam and purine-aminopropanol hybrids. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5637–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, S.; D’hooghe, M. Exploration of aziridine-and β-lactam-based hybrids as both bioactive substances and synthetic intermediates in medicinal chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 3643–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, R.; Biot, C.; Carrère-Kremer, S.; Kremer, L.; Guérardel, Y.; Gut, J.; Rosenthal, J.P.; Kumar, V. 4-Aminoquinoline-β-Lactam Conjugates: Synthesis, Antimalarial, and Antitubercular Evaluation. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2014, 83, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, V.; Hopper, M.; Patel, N.; Hall, D.; Wrischnik, L.A.; Land, K.M.; Kumar, V. Design and synthesis of β-amino alcohol based β-lactam–isatin chimeras and preliminary analysis of in vitro activity against the protozoal pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Cornier, P.G.; Boggián, D.B.; Mata, E.G.; Delpiccolo, C.M. Solid-phase based synthesis of biologically promising triazolyl aminoacyl (peptidyl) penicillins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornier, P.G.; Delpiccolo, C.M.; Mascali, F.C.; Boggián, D.B.; Mata, E.G.; Cárdenas, M.G.; Blank, V.C.; Roguin, L.P. In vitro anticancer activity and SAR studies of triazolyl aminoacyl (peptidyl) penicillins. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, L.; Mata, E.G. Solid-Supported Cross-Metathesis and a Formal Alkane Metathesis for the Generation of Biologically Relevant Molecules. ACS Comb. Sci. 2015, 17, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsbury, J.S.; Harrity, J.P.A.; Bonitatebus, P.J., Jr.; Hoveyda, A.H. A recyclable Ru-based metathesis catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, S.B.; Kingsbury, J.S.; Gray, B.L.; Hoveyda, A.H. Efficient and recyclable monomeric and dendritic Ru-based metathesis catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8168–8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, D.G.; Kataoka, O.; Garber, S.B.; Hoveyda, A.H. Efficient and recyclable monomeric and dendritic Ru-based metathesis catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 12288–12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

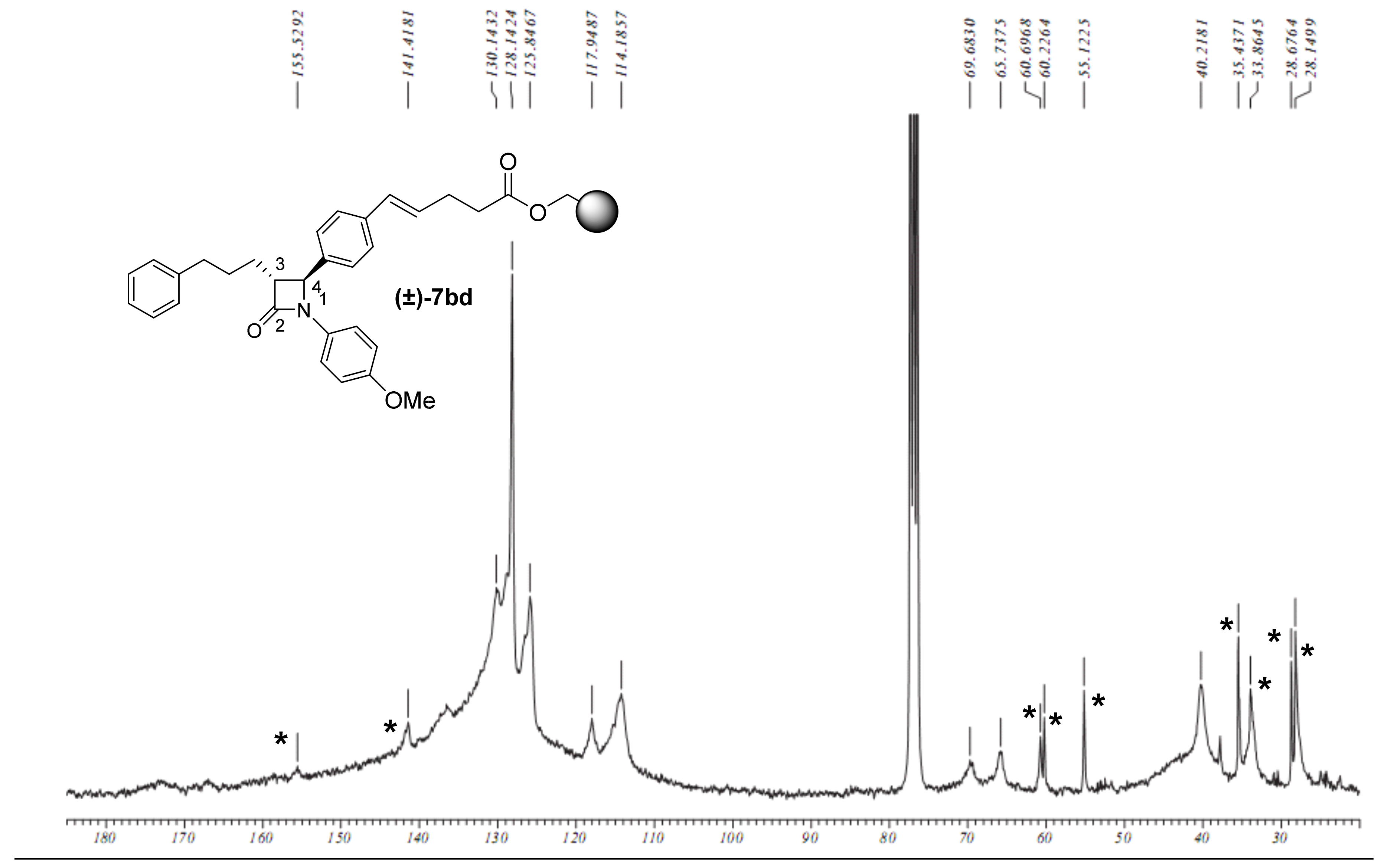

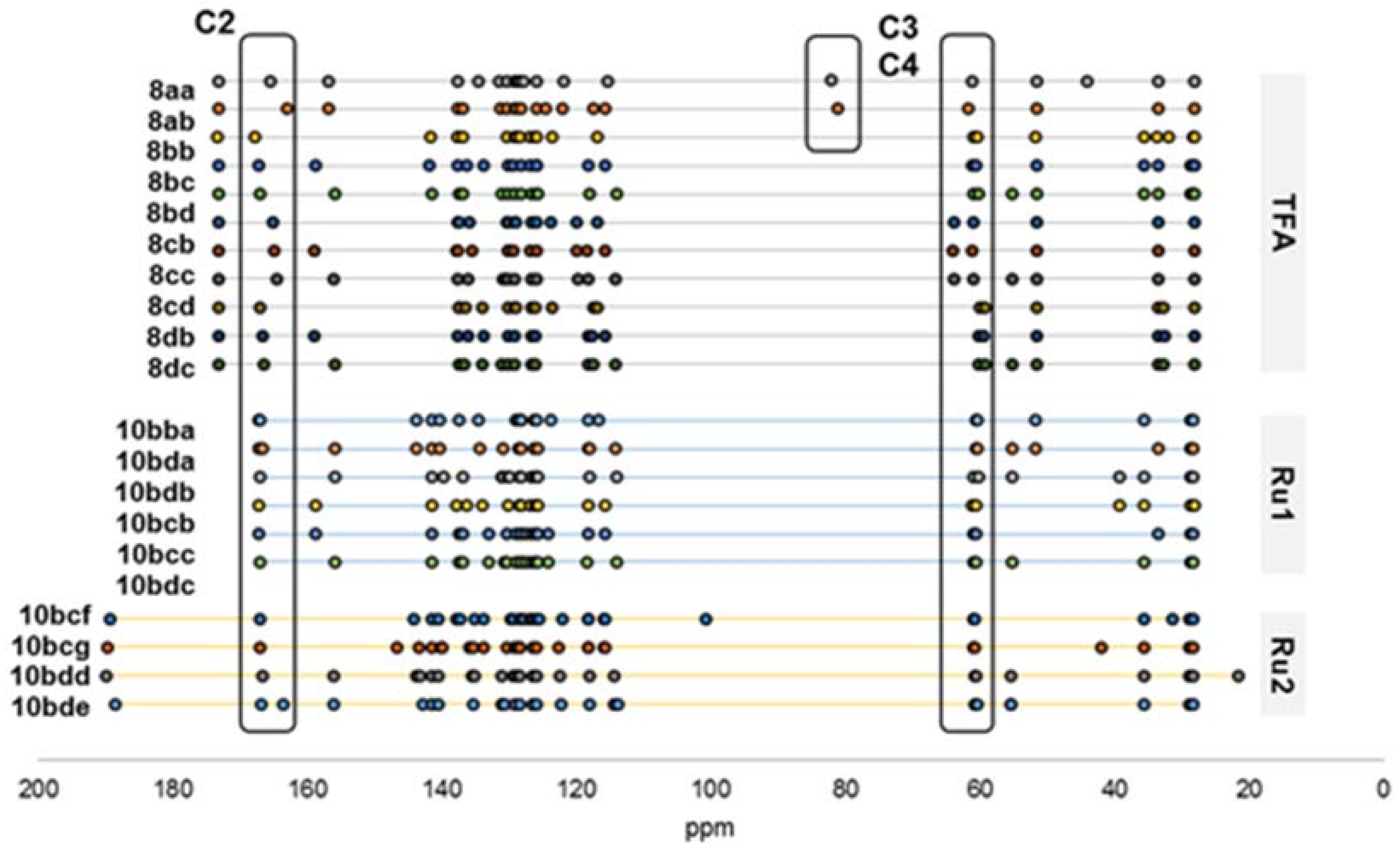

- Giralt, E.; Rizo, J.; Pedroso, E. Application of gel-phase 13C-NMR to monitor solid phase peptide synthesis. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 4141–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunshier, C.; Hametner, C. Gel-Phase 13C-NMR Spectroscopy of Selected Solid Phase Systems. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2007, 26, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

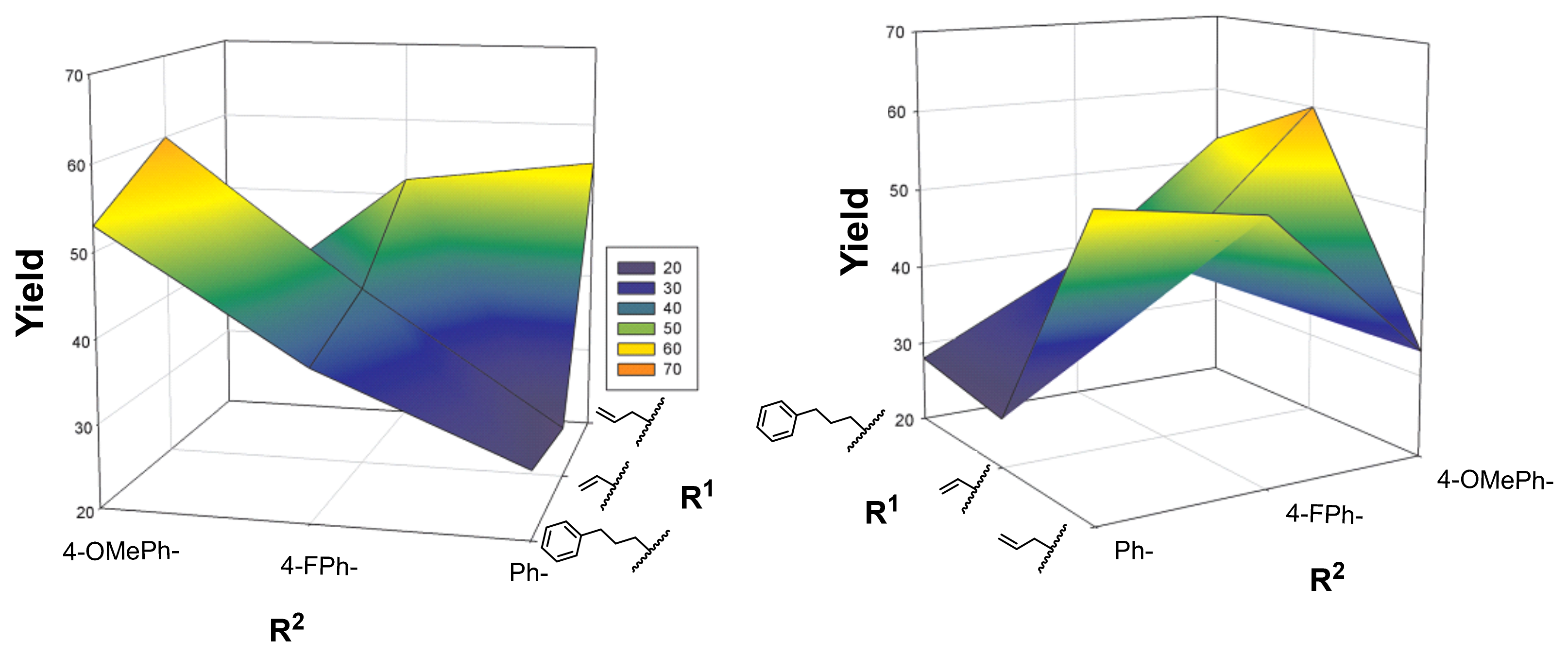

| Entry | Starting Material | 3,4 Configuration | R1 | R2 | Product | Yield (%) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

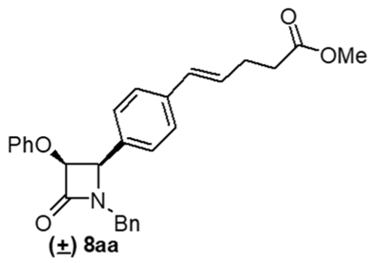

| 1 | 7aa | cis | PhO | Bn | 8aa | 58 |

| 2 | 7ab | cis | PhO | Ph | 8ab | 43 |

| 3 | 7bb | trans |  | Ph | 8bb | 28 |

| 4 | 7bc | trans |  | 4-FPh | 8bc | 38 |

| 5 | 7bd | trans |  | 4-MeOPh | 8bd | 53 |

| 6 | 7cb | trans |  | Ph | 8cb | 26 |

| 7 | 7cc | trans |  | 4-FPh | 8cc | 42 |

| 8 | 7cd | trans |  | 4-MeOPh | 8cd | 60 |

| 9 | 7db | trans |  | Ph | 8db | 55 |

| 10 | 7dc | trans |  | 4-FPh | 8dc | 52 |

| 11 | 7dd | trans |  | 4-MeOPh | 8dd | 33 |

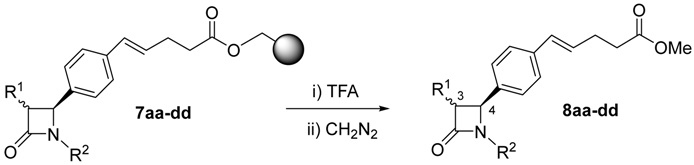

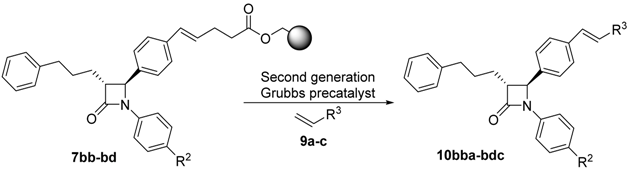

| Entry | Starting Material | R2 | R3 | Product | Yield (%) a | CM Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7bb | –H | MeO2C– c | 10bba | 25 | 87 |

| 2 | 7bd | –OMe | MeO2C– c | 10bda | 47 | 88 |

| 3 | 7bd | –OMe | Bn | 10bdb | 49 | 92 |

| 4 | 7bc | –F | Bn | 10bcb | 31 | 81 |

| 5 | 7bc | –F | 2-BrPh | 10bcc | 27 | 50 |

| 6 | 7bd | –OMe | 2-BrPh | 10bdc | 16 | 41 |

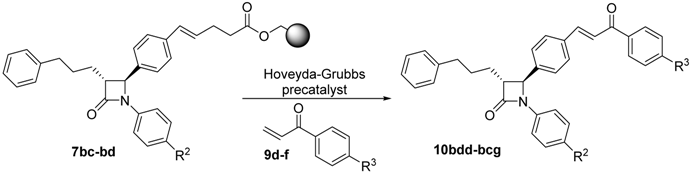

| Entry | Starting Material | R2 | R3 | Product | Yield (%) a | CM Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7bd | –OMe | –CH3 | 10bdd | 20 | 38 |

| 2 | 7bd | –OMe | –OCH3 | 10bde | 15 | 28 |

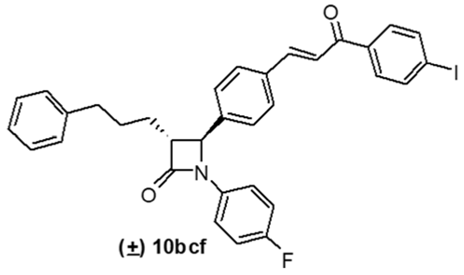

| 3 | 7bc | –F | –I | 10bcf | 22 | 58 |

| 4 | 7bc | –F | –CH2Ph | 10bcg | 20 c | 53 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Méndez, L.; Poeylaut-Palena, A.A.; Mata, E.G. Molecular Diversity by Olefin Cross-Metathesis on Solid Support. Generation of Libraries of Biologically Promising β-Lactam Derivatives. Molecules 2018, 23, 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051193

Méndez L, Poeylaut-Palena AA, Mata EG. Molecular Diversity by Olefin Cross-Metathesis on Solid Support. Generation of Libraries of Biologically Promising β-Lactam Derivatives. Molecules. 2018; 23(5):1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051193

Chicago/Turabian StyleMéndez, Luciana, Andrés A. Poeylaut-Palena, and Ernesto G. Mata. 2018. "Molecular Diversity by Olefin Cross-Metathesis on Solid Support. Generation of Libraries of Biologically Promising β-Lactam Derivatives" Molecules 23, no. 5: 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051193