New Limonoids from Hortia oreadica and Unexpected Coumarin from H. superba Using Chromatography over Cleaning Sephadex with Sodium Hypochlorite

Abstract

:1. Introduction

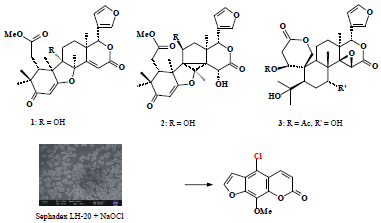

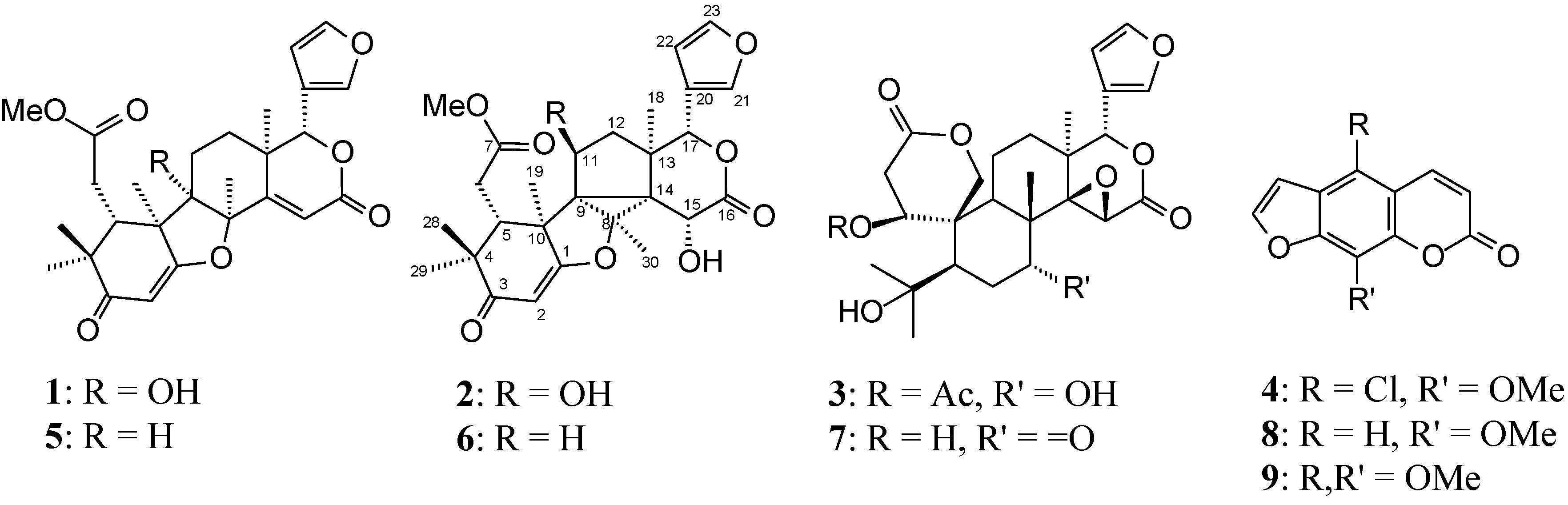

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Elucidation of New Compounds

| H | 1 | 2 | 3 | H | 4 | 4 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.04 (brd, 4.2) | 3 | 6.45 (d, 9.8) | 6.46 (d, 10.0) | ||

| 2a | 5.45 (s) | 5.49 (s) | 2.94 (dd, 16.8, 4.2) | 4 | 8.15 (d, 9.8) | 8.17 (d, 10.0) |

| 2b | 2.58 (dd, 16.8, 1.4) | 2' | 7.70 (d, 2.2) | 7.72 (d, 2.2) | ||

| 5 | 2.61 (m) | 2.71 (dd, 5.7, 3.3) | 2.25 (dd, 13.7, 2.6) | 3' | 6.92 (d, 2,2) | 6.93 (d, 2.2) |

| 6a | 2.57 (m) | 3.43 (dd, 18.8, 5.7) | 1.78 (m) | 8-OMe | 4.29 (s) | 4.28 (s) |

| 6b | 2.41 (dd, 18.8, 3.3) | 1.88 (m) | ||||

| 7 | 4.56 (t, 2.6) | |||||

| 9 | 2.72 (dd, 12.6, 6.6) | |||||

| 11a | 1.41 (m) | 4.43 (d, 4.8) | 1.92 (m) | |||

| 11b | 1.26 (m) | 1.83 (m) | ||||

| 12a | 1.79 (m) | 1.68 (m) | 1.69 (m) | |||

| 12b | 1.65 (m) | 1.64 (m) | ||||

| 15 | 6.37 (s) | 4.55 (s) | 3.51 (s) | |||

| 17 | 5.13 (s) | 5.72 (s) | 5.59 (s) | |||

| 18 | 1.21 (s) | 1.15 (s) | 1.29 (s) | |||

| 19a | 1.52 (s) | 1.54 (s) | 4.49 (d, 13.0) | |||

| 19b | 4.42 (d, 13.0) | |||||

| 21 | 7.53 (d, 0.4) | 7.42 (d, 1.6) | 7.42 (brs) | |||

| 22 | 6.51 (dd, 1.6, 0.4) | 6.46 (t, 1.6) | 6.33 (t, 1.4) | |||

| 23 | 7.45 (t, 1.6) | 7.42 (d, 1.6) | 7.41 (brs) | |||

| 28 | 1.19 (s) | 1.10 (s) | 1.12 (s) | |||

| 29 | 1.11 (s) | 1.19 (s) | 1.24 (s) | |||

| 30 | 1.71 (s) | 1.80 (s) | 0.95 (s) | |||

| OMe | 3.72 (s) | 3.63 (s) | ||||

| 9-OH | 2.94 (s) | |||||

| 11-OH | 2.88 (brs) | |||||

| 15-OH | 3.09 (brs) | |||||

| OCOMe | 2.15 (s) |

| C | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 178.8 | 179.7 | 182.2 | 180.6 | 80.0 | 70.3 |

| 2 | 102.3 | 101.3 | 99.2 | 99.8 | 35.7 | 39.0 |

| 3 | 202.0 | 202.2 | 202.7 | 201.9 | 169.4 | 171.3 |

| 4 | 44.9 | 44.3 | 45.0 | 44.9 | 80.7 | 79.5 |

| 5 | 42.3 | 42.3 | 43.9 | 45.4 | 53.6 | 49.6 |

| 6 | 31.5 | 32.6 | 32.0 | 31.8 | 23.5 | 38.2 |

| 7 | 174.7 | 173.2 | 174.8 | 173.9 | 73.2 | 213.2 |

| 8 | 90.2 | 89.3 | 75.0 | 75.5 | 43.0 | 52.1 |

| 9 | 80.5 | 56.4 | 49.1 | 46.8 | 43.3 | 48.0 |

| 10 | 50.6 | 48.0 | 50.3 | 47.6 | 45.6 | 45.4 |

| 11 | 29.8 | 21.8 | 71.0 | 23.2 | 17.5 | 21.4 |

| 12 | 25.9 | 30.3 | 42.7 | 29.7 | 25.8 | 32.9 |

| 13 | 37.2 | 37.7 | 45.3 | 45.5 | 38.8 | 36.4 |

| 14 | 168.4 | 167.1 | 48.6 | 48.2 | 68.9 | 65.3 |

| 15 | 116.8 | 116.0 | 64.2 | 64.1 | 56.6 | 52.1 |

| 16 | 164.5 | 164.3 | 172.0 | 171.5 | 167.0 | 166.7 |

| 17 | 79.6 | 78.9 | 80.5 | 79.9 | 78.1 | 77.5 |

| 18 | 21.5 | 20.9 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 17.5 | 15.8 |

| 19 | 19.1 | 25.8 | 22.1 | 22.8 | 65.6 | 67.8 |

| 20 | 119.7 | 119.6 | 120.4 | 120.4 | 120.2 | 120.1 |

| 21 | 142.0 | 142.0 | 141.6 | 141.7 | 141.3 | 141.3 |

| 22 | 110.5 | 110.4 | 110.4 | 110.0 | 109.8 | 110.1 |

| 23 | 143.2 | 143.0 | 143.1 | 143.4 | 143.3 | 142.2 |

| 28 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 23.1 | 22.9 | 21.1 | 20.6 |

| 29 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 28.3 | 27.6 | 30.3 | 26.1 |

| 30 | 27.0 | 31.1 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 18.4 | 32.7 |

| OMe | 52.3 | 52.0 | 52.0 | 52.6 | ||

| OCOMe | 21.4 |

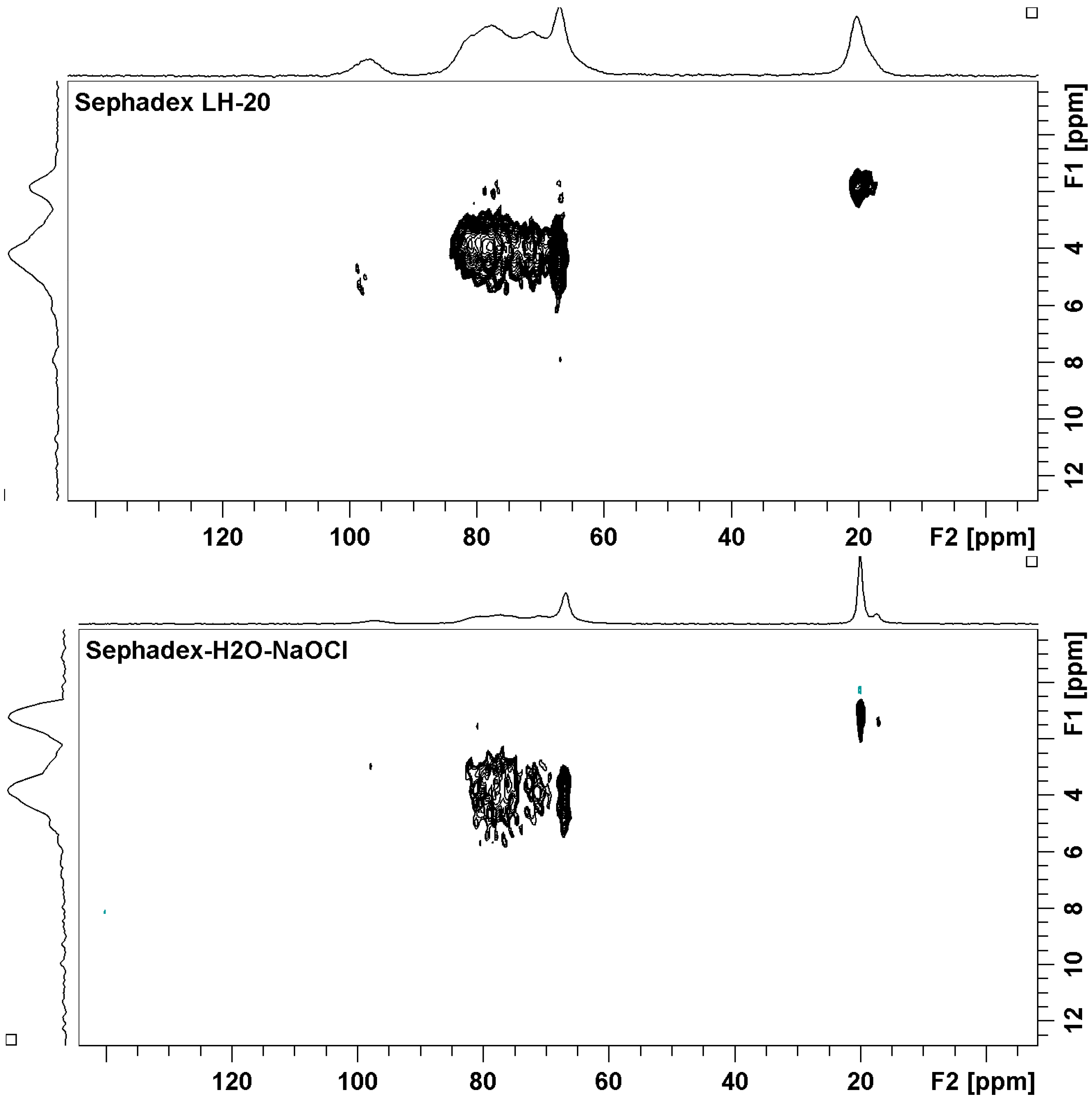

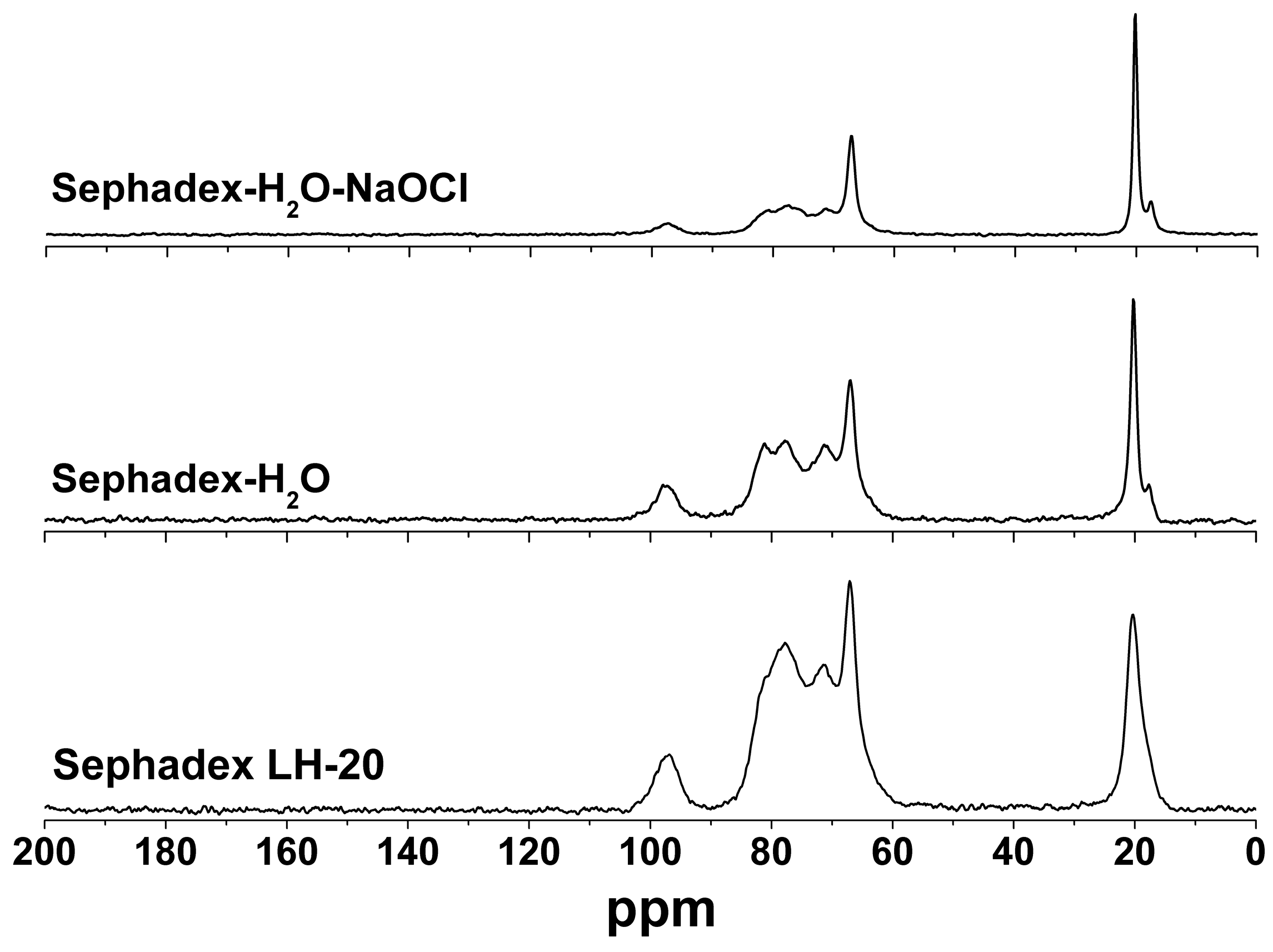

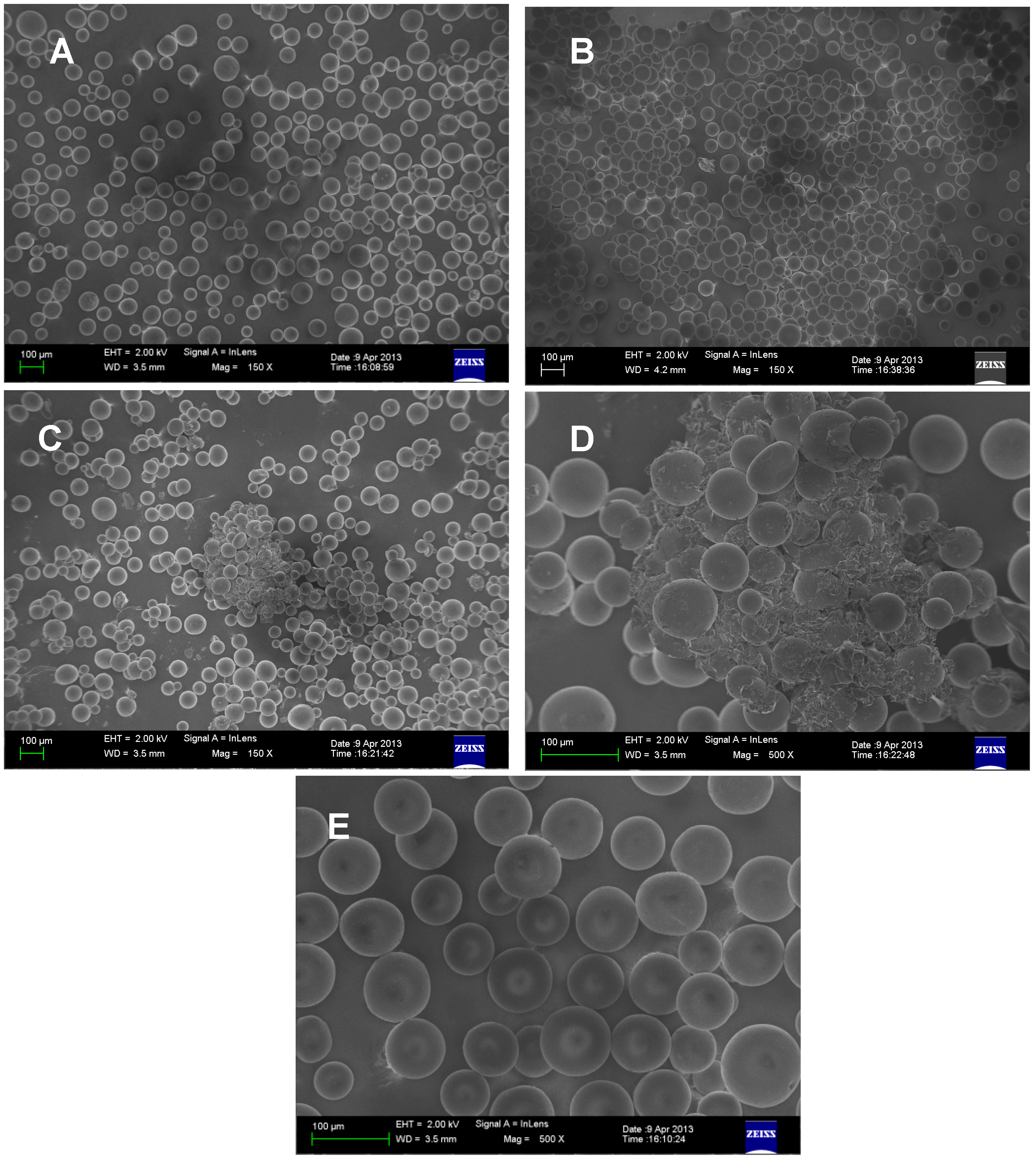

2.2. Sephadex LH-20 Analysis

2.3. Identification of Known Compounds

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Instrumentation

3.2. Cleaning Sephadex LH-20 and Repacked Column

3.3. Plant Material

3.4. Extraction and Isolation

3.5. Analytical Data

+33.47 (c 0.010, CHCl3); IR (film) νmax 3436 (OH), 1733 (carboxyl group), 1638 (α,β-unsaturated ketone) cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HSQC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3); COSY (400 MHz, CDCl3), HMBC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3): H-2→C-1, C-3, C-4, C-10, H-5→C-4, C-6, C-7, C-10, H-6→C-5, C-7, H-11b→C-12, C-13, H-12a→C-11, C-17, H-12b→C-14, C-18, H-15→C-8, C-13, C-14, C-16, H-17→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-18, C-20, C-21, C-22, H3-18→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17, H3-19→C-5, C-9, C-10, H-21→C-17, C-20, C-22, C-23, H-22→C-20, C-21, C-23, H-23→C-20, C-21, H3-28→C-3, C-4, C-5, C-29, H3-29→C-3, C-4, C-5, C-28, H3-30→C-8, C-14, OMe→C-7; HO-9→C-8, g-NOESY (400 MHz, CDCl3): irradiated HO-9→Me-18, Me-19, Me-30, Me-30→Me-19, Me-18, Me-19→HO-9, Me-29, Me-30; HRESIMS, 485.2173 (100; calcd for C27H32O8, M+ 485.2097), 507.1984 [M + Na+].

+33.47 (c 0.010, CHCl3); IR (film) νmax 3436 (OH), 1733 (carboxyl group), 1638 (α,β-unsaturated ketone) cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HSQC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3); COSY (400 MHz, CDCl3), HMBC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3): H-2→C-1, C-3, C-4, C-10, H-5→C-4, C-6, C-7, C-10, H-6→C-5, C-7, H-11b→C-12, C-13, H-12a→C-11, C-17, H-12b→C-14, C-18, H-15→C-8, C-13, C-14, C-16, H-17→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-18, C-20, C-21, C-22, H3-18→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17, H3-19→C-5, C-9, C-10, H-21→C-17, C-20, C-22, C-23, H-22→C-20, C-21, C-23, H-23→C-20, C-21, H3-28→C-3, C-4, C-5, C-29, H3-29→C-3, C-4, C-5, C-28, H3-30→C-8, C-14, OMe→C-7; HO-9→C-8, g-NOESY (400 MHz, CDCl3): irradiated HO-9→Me-18, Me-19, Me-30, Me-30→Me-19, Me-18, Me-19→HO-9, Me-29, Me-30; HRESIMS, 485.2173 (100; calcd for C27H32O8, M+ 485.2097), 507.1984 [M + Na+]. −251.27 (c 0.010, CHCl3); IR (film) νmax 3019 (OH), 1733 (carboxyl group), 1637 (α,β-unsaturated ketone) cm−1, 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HSQC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3); COSY (400 MHz, CDCl3), HMBC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3): H-2→C-1, C-10, H-5→C-7, C-10, C-14, C-19, H-6a→C-5, C-7, H-6b→C-7, H-11→C-9, C-10, C-13, C-14, H-12→C-11, C-13, C-14, H-15→C-9, C-13, C-14, C-16, H-17→C-13, C-14, C-20, C-21, C-22, H3-18→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17, H3-19→C-1, C-5, C-9, C-14, H-21→ C-20, C-22, C-23, H-22→C-20, C-21, C-23, H-23→C-20, C-22, H3-28→C-3, C-5, C-29, H3-29→C-3, C-5, C-28, H3-30→C-8, C-9, C-14, OMe→C-7, HO-11→C-9, C-12, HO-15→C-14, C-16; g-NOESY (400 MHz, CDCl3): irradiated H-17→H-15, H-5, H-11→Me-30, Me-19; HREIMS, 501.2119 (100; calcd for C27H32O9, M+ 501.2046), 523.1950 [M + Na+].

−251.27 (c 0.010, CHCl3); IR (film) νmax 3019 (OH), 1733 (carboxyl group), 1637 (α,β-unsaturated ketone) cm−1, 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HSQC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3); COSY (400 MHz, CDCl3), HMBC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3): H-2→C-1, C-10, H-5→C-7, C-10, C-14, C-19, H-6a→C-5, C-7, H-6b→C-7, H-11→C-9, C-10, C-13, C-14, H-12→C-11, C-13, C-14, H-15→C-9, C-13, C-14, C-16, H-17→C-13, C-14, C-20, C-21, C-22, H3-18→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17, H3-19→C-1, C-5, C-9, C-14, H-21→ C-20, C-22, C-23, H-22→C-20, C-21, C-23, H-23→C-20, C-22, H3-28→C-3, C-5, C-29, H3-29→C-3, C-5, C-28, H3-30→C-8, C-9, C-14, OMe→C-7, HO-11→C-9, C-12, HO-15→C-14, C-16; g-NOESY (400 MHz, CDCl3): irradiated H-17→H-15, H-5, H-11→Me-30, Me-19; HREIMS, 501.2119 (100; calcd for C27H32O9, M+ 501.2046), 523.1950 [M + Na+]. −46.80 (c 0.010, CHCl3); IR (film) νmax 3430 (OH), 1745 (carboxyl group) cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HSQC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3); COSY (400 MHz, CDCl3), HMBC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3): H-1→1-OC(O)Me, C-8, C-19, H-2a/ H-2b→C-1, C-3, C-10, H-5→C-4, C-6, C-7, C-9, C-10, C-19, Me-28, Me-29, H-6a/H-6b→C-5, C-7, C-10, H-7→C-5, C-8, Me-30, H-9→C-1, C-5, C-8, C-10, C-14, C-19, Me-30, H-11a/H-11b→C-10, C-12, H-12a/H-12b→C-13, C-14, Me-18, H-15→C-8, C-14, C-16, H-17→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-20, C-21, C-22, Me-18, H3-18→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17, H-19a/H-19b→C-1, C-3, C-5, C-9, C-10, H-21→C-20, C-22, C-23, H-22→C-20, C-21, C-23, H-23→C-20, C-21, C-22, H3-28→C-4, C-5, Me-29, H3-29→C-4, C-5, Me-28, H3-30→C-7, C-8, C-9, C-14; g-NOESY (400 MHz, CDCl3): irradiated H-1→H-5, H-9, H-9→H-5, Me-18, Me-30→Me-19, H-7; HREIMS, 533.2250 (100; calcd for C28H36O10, M+ 533.2308), 555.2088 [M + Na+], 571.1839 [M + K+].

−46.80 (c 0.010, CHCl3); IR (film) νmax 3430 (OH), 1745 (carboxyl group) cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HSQC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3); COSY (400 MHz, CDCl3), HMBC (400/100 MHz, CDCl3): H-1→1-OC(O)Me, C-8, C-19, H-2a/ H-2b→C-1, C-3, C-10, H-5→C-4, C-6, C-7, C-9, C-10, C-19, Me-28, Me-29, H-6a/H-6b→C-5, C-7, C-10, H-7→C-5, C-8, Me-30, H-9→C-1, C-5, C-8, C-10, C-14, C-19, Me-30, H-11a/H-11b→C-10, C-12, H-12a/H-12b→C-13, C-14, Me-18, H-15→C-8, C-14, C-16, H-17→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-20, C-21, C-22, Me-18, H3-18→C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17, H-19a/H-19b→C-1, C-3, C-5, C-9, C-10, H-21→C-20, C-22, C-23, H-22→C-20, C-21, C-23, H-23→C-20, C-21, C-22, H3-28→C-4, C-5, Me-29, H3-29→C-4, C-5, Me-28, H3-30→C-7, C-8, C-9, C-14; g-NOESY (400 MHz, CDCl3): irradiated H-1→H-5, H-9, H-9→H-5, Me-18, Me-30→Me-19, H-7; HREIMS, 533.2250 (100; calcd for C28H36O10, M+ 533.2308), 555.2088 [M + Na+], 571.1839 [M + K+].4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Severino, V.G.P.; Cazal, C.M.; Forim, M.R.; Silva, M.F.G.F.; Rodrigues-Filho, E.; Fernandes, J.B.; Vieira, P.C. Isolation of secondary metabolites from Hortia oreadica (rutaceae) leaves through high-speed counter-current chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 4275–4281. [Google Scholar]

- Severino, V.G.P.; Braga, P.A.C.; Silva, M.F.G.F.; Fernandes, J.B.; Vieira, P.C.; Theodoro, J.E.; Ellena, J.A. Cyclopropane- and spirolimonoids and related compounds from Hortia oreadica. Phytochemistry 2012, 76, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, P.A.C.; Severino, V.G.P.; Freitas, S.D.L.; Silva, M.F.G.F.; Fernandes, J.B.; Vieira, P.C.; Pirani, J.R.; Groppo, M. Dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives from Hortia species and their chemotaxonomic value in the Rutaceae. Biochem. Syst. Ecol 2012, 43, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.N.; Shoeb, A.; Kapil, R.S.; Popli, S.P. Toddanol and toddanone, two coumarins from Toddalia asiatica. Phytochemistry 1981, 20, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, C.; Furukawa, H.; Ishii, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Haginiwa, J. The chemical composition of Murraya paniculata. The structure of five new coumarins and one new alkaloid and the stereochemistry of murrangatin and related coumarins. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaul, J.; Philogène, E.; Bourgeois, P.; Poupat, C.; Ahond, A.; Potier, P. Contribution à la connaissance des Rutacées Américaines: Étude des feuilles de Tryphasia trifolia. J. Nat. Prod 1994, 57, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, M.; Ali, A.; Malla, A.M.; Silva, P.S.P.; Silva, M.R. A halogenated coumarin from Ficus krishnae. Chem. Pap 2011, 65, 735–738. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, L.E.C.; Casabó, J.; Monache, F.D.; Molins, E.; Espinosa, E.; Miravitlles, C. Hortialide A, a novel limonoid from Hortia colombiana. An. Quim 1998, 94, 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, L.E.C.; Menichini, F.; Monache, F.D. Tetranorterpenoids and dyhydrocinnamic acid from Hortia colombiana. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 2002, 13, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, N.; Morimoto, T.; Matsuo, K.; Nagai, S.-I.; Ueda, T.; Sakakibara, J.; Mizuno, N.; Esaki, K. The oxidized products of 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) with H2O2-NaOCl. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1991, 39, 2715–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, H.; Ramdayal, F. Guyanin, a novel tetranortriterpenoid.Structure elucidation by 2D NMR spectroscopy. Tetrahedron Lett 1986, 27, 1453–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, C.A.C.; Barrera, E.D.C.; Falla, D.S.G.; Murcia, G.D.; Suarez, L.E.C. Seco-Limonoids and quinoline alkaloids from Raputia heptaphylla and their antileishmanial activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull 2011, 59, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidoro, M.M.; Silva, M.F.G.F.; Fernandes, J.B.; Vieira, P.C.; Arruda, A.C.; Silva, S.C. Fitoquímica e Quimiossistemática de Euxylophora paraensis (Rutaceae). Quim. Nova 2012, 35, 2119–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.C.; Colarte, A.I.; Ghzaoui, A.E.; Durand, D.; Delarbre, J.L.; Bataille, B. A sugar cane native dextran as na innovative functional excipiente for the development of pharmaceutical tablets. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2008, 68, 319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingboe, J.; Nyström, E.; Sjövall, J. A versatile lipophilic Sephadex derivative for reversed-phase chromatography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1968, 152, 803–805. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, A.; Ito, T.; Horri, F.; Kitamaru, R.; Kobayashi, K.; Sumitomo, H. Cross-polarization magic angle spinning carbono-13 nuclear magnetic resonance study of linear dextran crystallized from poly(ethylene glycol)-water solution at a high temperature. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 1837–1841. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken,NJ,USA, 2005; pp. 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, D.D.; Bitter, H.-M.L.; Jerschow, A. Solid-state NMR spectroscopic methods in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 3096–3129. [Google Scholar]

- Teleman, A.; Kruus, K.; Ämmälahti, E.; Buchert, J.; Nurmi, K. Structure of dicarboxyl malto-oligomers isolated from hypochlorite-oxidised potato starch studied by 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Res 1999, 315, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilstam, U.; Weinmann, H. Trichloroisocyanuric acid: A safe and efficient oxidant. Org. Process. Res. Dev 2002, 6, 384–393. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, A.C.; Paixão, F.M.; Souza, M.C.B.V.; Ferreira, V.F. Cloreto isocianúrico e cloreto cianúrico: Aspectos gerais e aplicações em síntese orgânica. Quim. Nova 2006, 29, 520–527. [Google Scholar]

- Bryce, D.L.; Sward, G.D. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of the quadrupolar halogens: Chlorine-35/37, bromine-79/81, and iodine-127. Magn. Reson. Chem 2006, 44, 409–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, A.J.; Mills, R.W.; Briscoe, G.A.; Norton, E.L.; Geier, S.J.; Hung, I.; Zheng, S.; Autschbach, J.; Schurko, R.W. Solid-state chlorine NMR of group IV transition metal organometallic complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3317–3330. [Google Scholar]

- Perras, F.A.; Bryce, D.L. Direct investigation of covalently bound chlorine in organic compounds by solid-state 35Cl-NMR spectroscopy and exact spectral line-shape simulations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 4227–4230. [Google Scholar]

- Góral, J.; Zichy, V. Fourier transform Raman studies of materials and compounds of biological importance. Spectrochim. Acta 1990, 46A, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.F.G.F.; Soares, M.S.; Fernandes, J.B.; Vieira, P.C. Alkyl, aryl, alkylarylquinoline, and related alkaloids. Alkaloids Chem. Biol 2007, 64, 139–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.F.G.F.; Fernandes, J.B.; Forim, M.R.; Vieira, P.C.; Sá, I.C.G. Alkaloids derived from anthranilic acid: Quinoline, acridone, and quinazoline. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Ramawat, K.G., Mérillon, J.-M., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 715–860. [Google Scholar]

- Ikuta, A.; Nakamura, T.; Urabe, H. Indolopyridoquinazoline, furoquinoline and canthinone type alkaloids from Phellodendron amurense callus tissues. Phytochemistry 1998, 48, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawer, I.; Zielinska, A. 13C CP/MAS NMR studies of flavonoids. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2001, 39, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne, E.M.K.; Bandara, B.M.R.; Gunatilaka, A.A.L. Chemical constituents of three Rutaceae species from Sri Lanka. J. Nat. Prod 1992, 55, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A.I. Structural diversity and distribution of coumarins and chromones in the Rutales. In Chemistry and Chemical Taxonomy of the Rutales; Waterman, P.G., Grundon, M.F., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1983; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, J.M.J.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cavaleiro, J.A.S. Chromones and flavanones from Artemisia campestris subsp maritime. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1421–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, M.K.; Ahn, M.J.; Kim, J.J. One step purification of flavanone glycosides from Poncirus trifoliata by centrifugal partition Chromatography. J. Sep. Sci 2007, 30, 2693–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terezan, A.P.; Rossi, R.A.; Almeida, R.N.A.; Freitas, T.G.; Fernandes, J.B.; Silva, M.F.G.F.; Vieira, P.C.; Bueno, O.C.; Pagnocca, F.C.; Pirani, J.R. Activities of extracts and compounds from Spiranthera odoratissima St. Hil. (Rutaceae) in leaf-cutting ants and their symbiotic fungus. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 2010, 21, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppo, M.; Kallunki, J.A.; Pirani, J.R. Synonymy of Hortia arbórea with H. brasiliana (Rutaceae) and a new species from Brazil. Brittonia 2005, 57, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Groppo, M.; Pirani, J.R. A revision of HORTIA (Rutaceae). Syst. Bot 2012, 37, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Samples Availability: Samples of the compounds 1–4 are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Severino, V.G.P.; De Freitas, S.D.L.; Braga, P.A.C.; Forim, M.R.; Da Silva, M.F.d.G.F.; Fernandes, J.B.; Vieira, P.C.; Venâncio, T. New Limonoids from Hortia oreadica and Unexpected Coumarin from H. superba Using Chromatography over Cleaning Sephadex with Sodium Hypochlorite. Molecules 2014, 19, 12031-12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190812031

Severino VGP, De Freitas SDL, Braga PAC, Forim MR, Da Silva MFdGF, Fernandes JB, Vieira PC, Venâncio T. New Limonoids from Hortia oreadica and Unexpected Coumarin from H. superba Using Chromatography over Cleaning Sephadex with Sodium Hypochlorite. Molecules. 2014; 19(8):12031-12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190812031

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeverino, Vanessa G.P., Sâmya D.L. De Freitas, Patrícia A.C. Braga, Moacir Rossi Forim, M. Fátima das G.F. Da Silva, João B. Fernandes, Paulo C. Vieira, and Tiago Venâncio. 2014. "New Limonoids from Hortia oreadica and Unexpected Coumarin from H. superba Using Chromatography over Cleaning Sephadex with Sodium Hypochlorite" Molecules 19, no. 8: 12031-12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190812031

APA StyleSeverino, V. G. P., De Freitas, S. D. L., Braga, P. A. C., Forim, M. R., Da Silva, M. F. d. G. F., Fernandes, J. B., Vieira, P. C., & Venâncio, T. (2014). New Limonoids from Hortia oreadica and Unexpected Coumarin from H. superba Using Chromatography over Cleaning Sephadex with Sodium Hypochlorite. Molecules, 19(8), 12031-12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190812031