Synthesis of a Highly Luminescent Three-Dimensional Pyrene Dye Based on the Spirobifluorene Skeleton

Abstract

:Introduction

Results and Discussion

| dye | λab[nm] | ε (×105) [l/mol・cm] | log ε | λem[nm] | Φ | τ [ns] | kf (×108) [S-1] | kisc + knr (×107) [S-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-PySBF | 360 | 1.31 | 5.12 | 441 | 0.92 | 1.52 | 6.1 | 5.3 |

| 2-PyF | 359 | 0.71 | 4.85 | 421 | 0.90 | 1.88 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

Conclusions

Experimental

Instruments

Materials

Acknowledgements

Appendix

- Samples Availability: Available from GK.

References and Notes

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Wakamiya, T.; Matsubara, Y.; Yoshida, Z. Light-Emitting Efficiency Tuning of Rod-Shaped π-Conjugated Systems by Donor and Acceptor Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9332–9333. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Ochi, T.; Wakamiya, T.; Matsubara, Y.; Yoshida, Z. New Fluorophores with Rod-Shaped Polycyano π-Conjugated Structures: Synthesis and Photophysical Properties. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Matsubara, Y.; Ochi, T.; Wakamiya, T.; Yoshida, Z. How the π-Conjugation Length Affects the Fluorescence Emission Efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13867–13869. [Google Scholar]

- Kanibolotsky, A.L.; Berridge, R.; Skabara, P.J.; Perepichka, I.F.; Bradley, D.D.C.; Koeberg, M. Synthesis and Properties of Monodisperse Oligofluorene-Functionalized Truxenes: Highly Fluorescent Star-Shaped Architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13695–13702. [Google Scholar]

- Leventis, N.; Rawashdeh, A.M.M.; Elder, I.A.; Yang, J.; Dass, A.; Sotiriou-Leventis, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Ru(II) Tris(1,10-phenanthroline)-Electron Acceptor Dyads Incorporating the 4-Benzoyl-N-methylpyridinium Cation or N-Benzyl-N‘-methyl Viologen. Improving the Dynamic Range, Sensitivity, and Response Time of Sol−Gel-Based Optical Oxygen Sensors. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barltrop, J.A.; Coyle, J.D. Principles of Photochemistry; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Sagari, T.P.I.; Spehr, T.; Siebert, A.; Fuhmann-Lieker, T.; Salbeck, J. Spiro Compounds for Organic Optoelectronics. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1011–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Cocherel, N.; Poriel, C.; Vignau, L.; Bergamini, J.; Rault-Berthelot, J. A New Blue Emitter for Nondoped Organic Light Emitting Diode Applications. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirion, D.; Poriel, C.; Barriere, F.; Metivier, R.; Jeannin, O.; Rault-Berthelot, J. Tuning the Optical Properties of Aryl-Substituted Dispirofluorene-indenofluorene Isomers through IntramolecularExcimer formation. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4794–4797. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Niu, Z.Q.; Zhou, Q.F.; Ma, Y.; Pei, J. Three-Dimensional Architectures for Highly Stable Pure Blue Emission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 113414–113415. [Google Scholar]

- Pudzich, R.; Fuhrmann-Lieker, T.; Salbeck, J. Spiro Compounds for Organic Electroluminescence and Related Applications. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2006, 199, 83–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, M.; Boo, B.H. Second molecular hyperpolarizability of 2,2′-diamino-7,7′-dinitro-9,9′-spirobifluorene: An experimental study on third-order nonlinear optical properties of a spiroconjugateddimer. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 2593–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poriel, C.; Ferrand, Y.; Maux, P.L.; Rault-Berthelot, J.; Simonneaux, G. Organic Cross-Linked Electropolymers as Supported Oxidation Catalysts: Poly((tetrakis(9,9‘spirobifluorenyl)porphyrin)-manganese) Films. Inorg.Chem. 2004, 43, 5086–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poriel, C.; Ferrand, Y.; Maux, P.L.; Paul, C.; Rault-Berthelot, J.; Simonneaux, G. Poly(ruthenium carbonyl spirobifluorenylporphyrin): A new polymer used as a catalytic device for carbene transfer. Chem. Commun. 2003, 2308–2309. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.T.; Ku, S.Y.; Cheng, Y.M.; Lin, X.Y.; Hung, Y.Y.; Pu, S.C.; Chou, P.T.; Lee, G.H.; Peng, S.M. Synthesis, Structures, and Photoinduced Electron Transfer Reaction in the 9,9‘-Spirobifluorene-Bridged Bipolar Systems. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.Y.; Wong, K.T.; Chou, P.T.; Cheng, Y.M. yntheses and spectroscopic studies of spirobifluorene-bridged bipolar systems; photoinduced electron transfer reactions. Chem. Commun. 2002, 2874–2875. [Google Scholar]

- Sartin, M.M.; Shu, C.; Bard, A.J. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of a Spirobifluorene-Linked Bisanthracene: A Possible Simultaneous, Two-Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5354–5360. [Google Scholar]

- Kowada, T.; Matsuyama, Y.; Ohe, K. Synthesis, Characterization, and Photoluminescence of Thiophene-Containing Spiro Compounds. Synlett 2008, 12, 1902–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, R.; Sato, T.; Kojima, T.; Hosokawa, K.; Koyama, Y.; Takata, T. 9,9′-Spirobifluorene-Containing Polycarbonates: Transparent Polymers with High Refractive Index and Low Birefringence. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 3658–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Luo, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Pei, J. Highly stable blue light-emitting materials with a three-dimensional architecture: Improvement of charge injection and electroluminescence performance. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.L., Lin; Wong, K.T.; Hou, T.H.; Hung, W.Y. A Novel Ambipolar Spirobifluorene Derivative that Behaves as an Efficient Blue-Light Emitter in Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 4511–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocherel, N.; Poriel, C.; Rault-Berthelot, J.; Barriere, F.; Audebrand, N.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Vignau, L. New 3π-2Spiro Ladder-Type Phenylene Materials: Synthesis, Physicochemical Properties and Applications in OLEDs. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 11328–11342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Fujimoto, K.; Furusho, M.; Maeda, H.; Nanai, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Inouye, M. Highly Emissive -Conjugated AlkynylpyreneOligomers: Their Synthesis and Photophysical Properties. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 1530–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Oyamada, T.; Akiyama, S.; Yahiro, M.; Saigou, M.; Shiro, M.; Sasabe, H.; Adachi, C. Unusual photoluminescence characteristics of tetraphenylpyrene (TPPy) in various aggregated morphologies. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 421, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchimura, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Araoka, F.; Watanabe, J.; Takezoe, H.; Konishi, G. Development of Laser Dyes to Realize Low Threshold in Dye-doped Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Lasers. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 4473–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Uchimura, M.; Araoka, F.; Konishi, G.; Watanabe, J.; Takezoe, H. Extremely Low Threshold in a Pyrene-doped Distributed Feedback Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Laser. Appl. Phys. Express 2009, 2, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira-Duarte, T.M.; Simon, S.C.; Wagner, M.; Druzhinin, S.I.; Zachariasse, K.A.; Müllen, K. Polypyrene Dendrimers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 10175–10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweig, A.; Weidner, U.; Hellwinkel, D.; Krapp, W. Spiroconjugation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1973, 12, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocherel, N.; Poriel, C.; Jeannin, O.; Yassin, A.; Rault-Berthelot, J. The synthesis, physicochemical properties and anodic polymerization of a novel ladder pentaphenylene. Dyes Pigm. 2009, 83, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poriel, C.; Liang, J.J.; Rault-Berthelot, J.; Barriere, F.; Cocherel, N.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Horhant, D.; Virboul, M.; Alcaraz, G.; Audebrand, N.; Vignau, L.; Huby, N.; Wantz, G.; Hirsch, L. Dispirofluorene-Indenofluorene Derivatives as New Building Blocks for Blue Organic Electroluminesent Devices and Electroactive Polymers. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 10055–10069. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, S.T. Highly Efficient Non-Doped Blue Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Fluorene Derivatives with High Thermal Stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005, 15, 1716–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, N.; dos Santos, D.A.; Guo, S.; Cornil, J.; Fahlman, M.; Salbeck, J.; Schenk, H.; Arwin, H.; Bredas, J.L.; Salanek, W.R. Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of Electroluminescent Spiro-type Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 2542–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

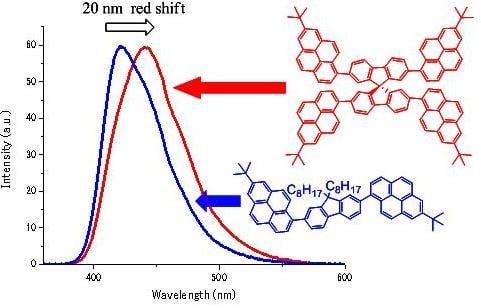

- This phenomenon is thought to be caused by intramolecular overlapping of the electron clouds of the 2,7-dipyrenylfluorene units. Few researchers have successfully observed distinct and strong spiroconjugation in the excited state [29,30]. However, in general, observed spiroconjugations were weak [31]. For example, in ref. [31], the authors reported that a compound in which two pyrenes were introduced into the spirobifluorene skeleton (2,7-dipyrene-9,9′-spirobifluorene, SDPF) showed a red-shift of 4 nm (in the ground state) and 1 nm (in the excited state) in comparison with a model compound, 2,7-dipyrene-9,9′-dimethyl fluorene (DPF). Futhermore in ref. [32], the authors compared UV-Vis spectra between a spiro-compound and an appropriate model compound by using MO calculations. However, to the best of our knowledge, no comparison between a 2,7-diarylfluorene and an appropriate spiro-compound (2,2’,7,7’-tetraarylspirobifluorene) has been carried out yet to investigate the spiroconjugation by experimental methods. This pyrene-fluorene-conjugated compound (4-PySBF) exhibited extremely large red-shift of fluorescence (20 nm). This phenomenon is very interesting. We intend to calculate the electron states of these compounds in the ground and excited states by the MO method and discuss this conjugation system in greater detail.

- Maeda, H.; Maeda, T.; Mizuno, K.; Fujimoto, K.; Shimizu, H.; Inouye, M. Alkynylpyrenesas Improved Pyrene-Based Biomolecular Probes with the Advantages of High Fluorescence Quantum Yields and Long Absorption/Emission Wavelengths. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafi, A.A.; Wilkinson, F. Charge Transfer Effects on the Efficiency of Singlet Oxygen Production Following Oxygen Quenching of Excited Singlet and Triplet States of Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Acetonitrile. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000, 104, 5747–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyushin, S.; Ikarugi, M.; Goto, M.; Hiratsuka, H.; Matsumoto, H. Synthesis and Electronic Properties of 9,10-Disilylanthracenes. Organometallics 1996, 15, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Usui, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Mori, S. Mechanism on the Efficient Formation of Singlet Oxygen by Energy Transfer from Excited Singlet and Triplet States of Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1992, 65, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, A.J.; McGarvey, D.J.; Truscott, T.G.; Lambert, C.R.; Land, E.J. Effect of Oxygen-enhanced Intersystem Crossing on the observartion efficiency of Formation of Singlet Oxygen. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1990, 86, 3075–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrene has a kisc value of 1.2 × 106 S−1 in cyclohexane, see Kikuchi, K. A new method for determining the efficiency of enhanced intersystem crossing in fluorescence quenching by molecular oxygen. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1991, 183, 103–106. [CrossRef]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Sumi, K.; Konishi, G.-i. Synthesis of a Highly Luminescent Three-Dimensional Pyrene Dye Based on the Spirobifluorene Skeleton. Molecules 2010, 15, 7582-7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15117582

Sumi K, Konishi G-i. Synthesis of a Highly Luminescent Three-Dimensional Pyrene Dye Based on the Spirobifluorene Skeleton. Molecules. 2010; 15(11):7582-7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15117582

Chicago/Turabian StyleSumi, Kentaro, and Gen-ichi Konishi. 2010. "Synthesis of a Highly Luminescent Three-Dimensional Pyrene Dye Based on the Spirobifluorene Skeleton" Molecules 15, no. 11: 7582-7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15117582