Synthesis of Sulfonamides and Evaluation of Their Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Activity

Abstract

:Introduction

Results and Discussion

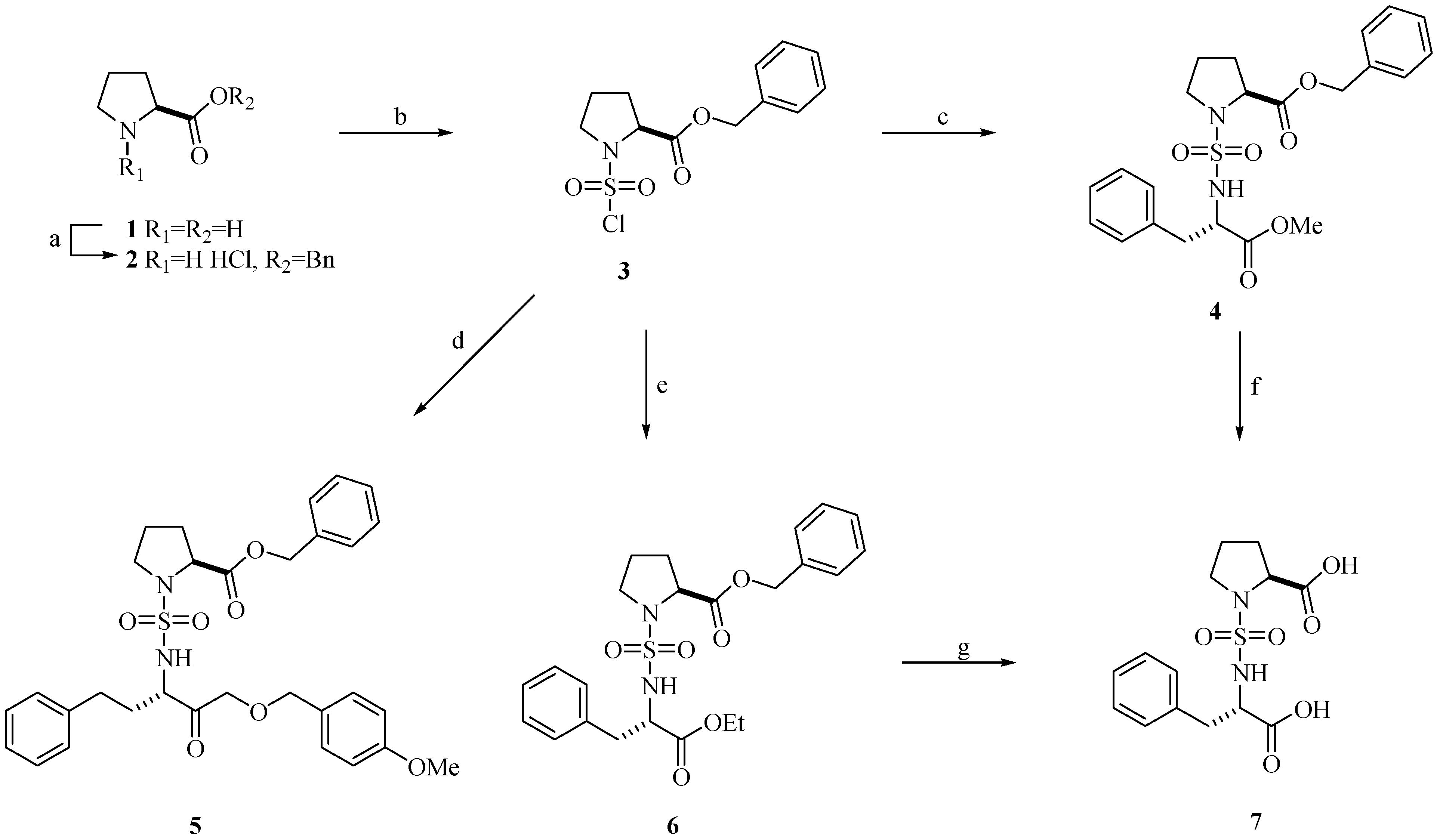

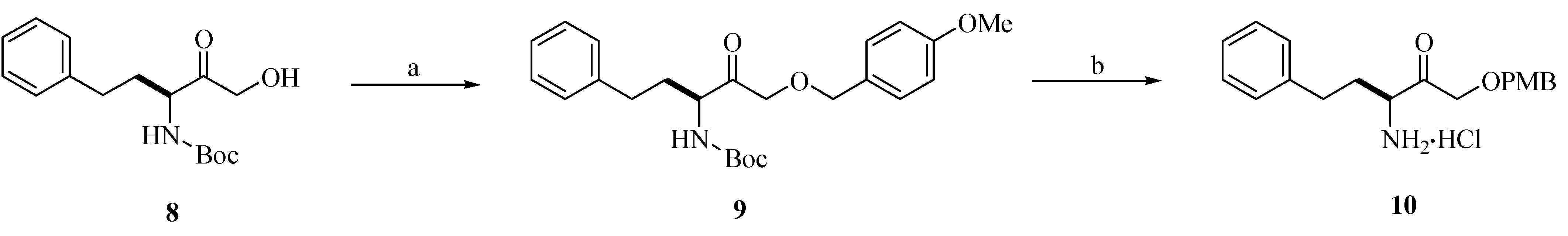

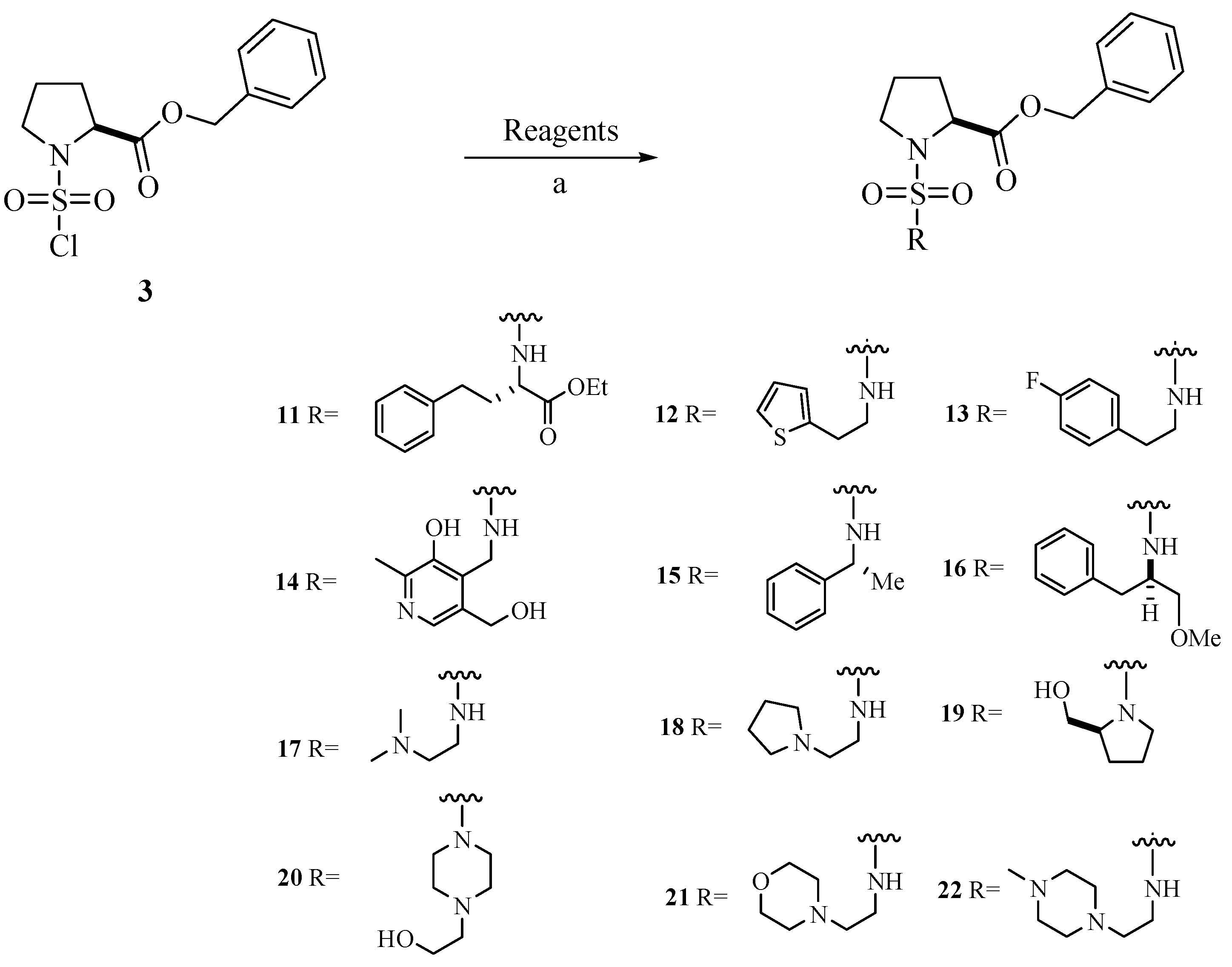

Chemistry

Biological Activity

| Compound | IC50 cells (μM)a |

|---|---|

| 7 | 40.3 |

| 13 | 36.8 |

| 14 | 25.3 |

| 16 | 21.5 |

| 20 | 2.8 |

| 22 | 12.3 |

| 4, 6, 11–12, 15, 17–19, and 21 | >100 |

| Sodium butyrateb | 140 |

| Trichostatin Ac | 0.0046 |

- a The values are means of three experiments.

- b,c Reference materials.

Conclusions

Experimental

General

Biology: In Vitro Inhibition of Histone Deacetylase

Chlorosulfonyl-L-proline benzyl ester (3)

General procedure for coupling reaction of chlorosulfonyl-L-proline benzyl ester (3) and several amines

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

References

- Vigushin, D. M.; Coombes, R. C. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Anti–Cancer Drugs 2002, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] Vigushin, D. M.; Coombes, R. C. Targeted histone deacetylase inhibition for cancer therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targ. 2004, 4, 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, A.; Massa, S.; Rotili, D.; Cerbara, I.; Valente, S.; Pezzi, R.; Simeoni, S.; Ragno, R. Histone deacetylation in epigenetics: an attractive target for anticancer therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2005, 25, 261–309. [Google Scholar] Dangond, F.; Henriksson, M.; Zardo, G.; Caiafa, P.; Ekstrom, T. J.; Gray, S. G. Differential expression of class I HDACs: roles of cell density and cell cycle. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 19, 773–777. [Google Scholar]

- Imre, G.; Gekeler, V.; Leja, A.; Beckers, T.; Boehm, M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors suppress the inducibility of nuclear factor-kappaB by tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor-1 down-regulation. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5409–5418. [Google Scholar] O'Connor, O. A.; Heaney, M. L.; Schwartz, L.; Richardson, S.; Willim, R.; MacGregor–Cortelli, B.; Curly, T.; Moskowitz, C.; Portlock, C.; Horwitz, S.; Zelenetz, A. D.; Frankel, S.; Richon, V.; Marks, P.; Kelly, W. K. Clinical experience with intravenous and oral formulations of the novel histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 166–173. [Google Scholar] Mayo, M. W.; Denlinger, C. E.; Broad, R. M.; Yeung, F.; Reilly, E. T.; Shi, Y.; Jones, D. R. Ineffectiveness of histone deacetylase inhibitors to induce apoptosis involves the transcriptional activation of NF-kappa B through the Akt pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18980–18989. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T.; Nagano, Y.; Kouketsu, A.; Matsuura, A.; Maruyama, S.; Kurotaki, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Miyata, N. Novel inhibitors of human histone deacetylases: design, synthesis, enzyme inhibition, and cancer cell growth inhibition of SAHA-based non-hydroxamates. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] Bouchain, G.; Delorme, D. Novel hydroxamate and anilide derivatives as potent histone deacetylase inhibitors: synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 2359–2372. [Google Scholar] Shinji, C.; Maeda, S.; Imai, K.; Yoshida, M.; Hashimoto, Y.; Miyachi, H. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of cyclic amide/imide-bearing hydroxamic acid derivatives as class-selective histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 7625–7651. [Google Scholar] Kim, H. M.; Lee, K.; Park, B. W.; Ryu, D. K.; Kim, K.; Lee, C. W.; Park, S. K.; Han, J. W.; Lee, H. Y.; Lee, H. Y.; Han, G. Synthesis, enzymatic inhibition, and cancer cell growth inhibition of novel δ-lactam-based histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4068–4070. [Google Scholar] Fournel, M.; Trachy–Bourget, M. C.; Yan, P. T.; Kalita, A.; Bonfils, C.; Beaulieu, C.; Frechette, S.; Leit, S.; Abou–Khalil, E.; Woo, S. H.; Delorme, D.; MacLeod, A. R.; Besterman, J. M.; Li, Z. Sulfonamide anilides, a novel class of histone deacetylase inhibitors, are antiproliferative against human tumors. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4325–4330. [Google Scholar] Owa, T.; Yoshino, H.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Nagasu, T. Cell cycle regulation in the G1 phase: a promising target for the development of new chemotherapeutic anticancer agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 1487–1503. [Google Scholar] Bouchain, G.; Delorme, D. Novel hydroxamate and anilide derivatives as potent histone deacetylase inhibitors: synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 2359–2372. [Google Scholar] Uesato, S.; Kitagawa, M.; Nagaoka, Y.; Maeda, T.; Kuwajima, H.; Yamori, T. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors: N-hydroxycarboxamides possessing a terminal bicyclic aryl group. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 1347–1349. [Google Scholar] Lavoie, R.; Bouchain, G.; Frechette, S.; Woo, S. H.; Abou–Khalil, E.; Leit, S.; Fournel, M.; Yan, P. T.; Trachy–Bourget, M. C.; Beaulieu, C.; Li, Z.; Besterman, J.; Delorme, D. Design and synthesis of a novel class of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2847–2850. [Google Scholar]

- Angibaud, P.; Arts, J.; Van Emelen, K.; Poncelet, V.; Pilatte, I.; Roux, B.; Van Brandt, S.; Verdonck, M.; De Winter, H.; Ten Holte, P.; Marien, A.; Floren, W.; Janssens, B.; Van Dun, J.; Aerts, A.; Van Gompel, J.; Gaurrand, S.; Queguiner, L.; Argoullon, J. M.; Van Hijfte, L.; Freyne, E.; Janicot, M. Discovery of pyrimidyl-5-hydroxamic acids as new potent histone deacetylase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, P. W.; Bandara, M.; Butcher, C.; Finn, A.; Hollinshead, R.; Khan, N.; Law, N.; Murthy, S.; Romero, R.; Watkins, C.; Andrianov, V.; Bokaldere, R. M.; Dikovska, K.; Gailite, V.; Loza, E.; Piskunova, I.; Starchenkov, I.; Vorona, M.; Kalvinsh, I. Novel sulfonamide derivatives as inhibitors of histone deacetylase. Helv. Chim. Acta 2005, 88, 1630–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchain, G.; Leit, S.; Frechette, S.; Khalil, E. A.; Lavoie, R.; Moradei, O.; Woo, S. H.; Fournel, M.; Yan, P. T.; Kalita, A.; Trachy–Bourget, M. C.; Beaulieu, C.; Li, Z.; Robert, M. F.; MacLeod, A. R.; Besterman, J. M.; Delorme, D. Development of potential antitumor agents. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a new set of sulfonamide derivatives as histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Karthikeyan, C.; Shrivastava, S. K.; Trivedi, P. QSAR Modeling of Sulfonamide Inhibitors of Histone Deacetylase. Internet Electron. J. Mol. Des. 2006, 5, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, A.; Reed, N. N.; Ashley, J. A.; Janda, K. D. Convenient synthesis of L-proline benzyl ester. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 3119–3122. [Google Scholar] Cheeseright, T. J.; Edwards, A. J.; Elmore, D. T.; Jones, J. H.; Raissi, M.; Lewis, E. C. Azasulfonamidopeptides as peptides bond hydrolysis transition state analogues. Part I: Synthetic approaches. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1 1994, 12, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Berredjem, M.; Winum, J. Y.; Toupet, L.; Masmoudi, O.; Aouf, N. E.; Montero, J. L. N-Chlorosulfonyloxazolidin-2-ones: Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity Toward Aminoesters. Synth. Commun. 2004, 34, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Tsukatani, M.; Taguchi, H.; Yokoi, T.; Bryant, S. D.; Lazarus, L. H. Amino acids and peptides. LII. Design and synthesis of opioid mimetics containing a pyrazinone ring and examination of their opioid receptor binding activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 46, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] Jung, J. C.; Avery, M. A. An efficient synthesis of cyclic urethanes from Boc-protected amino acids through a metal triflate-catalyzed intramolecular diazo carbonyl insertion reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 7969–7972. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, C. R.; Chittiboyina, A. G.; Kache, R.; Jung, J. C.; Watkins, E. B.; Avery, M. A. The trimethylsilyl xylyl (TIX) ether: a useful protecting group for alcohols. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, D. D.; Armarego, L. F.; Perrin, D. R. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 2nd ed.; Pergamon Press: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, D. J. Graded Responses. In Probit Analyses, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1962; Chapter 10. [Google Scholar] Yoshida, M.; Kijima, M.; Akita, M.; Beppu, T. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 17174–17179. [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseright, T. J.; Daenke, S.; Elmore, D. T.; Jones, J. H. Azasulfonamidopeptides as peptide bond hydrolysis transition state analogues. Part 2. Potential HIV-1 proteinase inhibitor. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1 1994, 14, 1953–1955. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from authors.

© 2007 by MDPI (http://www.mdpi.org). Reproduction is permitted for noncommercial purposes.

Share and Cite

Oh, S.; Moon, H.; Son, I.; Jung, J. Synthesis of Sulfonamides and Evaluation of Their Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Activity. Molecules 2007, 12, 1125-1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/12051125

Oh S, Moon H, Son I, Jung J. Synthesis of Sulfonamides and Evaluation of Their Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Activity. Molecules. 2007; 12(5):1125-1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/12051125

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Seikwan, Hyung–In Moon, Il–Hong Son, and Jae–Chul Jung. 2007. "Synthesis of Sulfonamides and Evaluation of Their Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Activity" Molecules 12, no. 5: 1125-1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/12051125

APA StyleOh, S., Moon, H., Son, I., & Jung, J. (2007). Synthesis of Sulfonamides and Evaluation of Their Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Activity. Molecules, 12(5), 1125-1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/12051125